Abstract

To address healthcare workforce shortages, Poland has experienced a significant expansion in medical education, characterized by a tripling of accredited institutions and a fourfold increase in student admissions over the past two decades. However, in 2024, the suspension of admission quotas for six newly established universities was due to concerns over accreditation of medical degree programs (MD). Given the ongoing discussions in the European Union (EU) member states about the importance of maintaining educational quality and upholding quality standards, this study seeks to thoughtfully examine trends in admissions and the institutional growth of medical education from 2004 to 2024. It draws upon the policies established by the Ministry of Health and the Polish Accreditation Committee (PKA) throughout this timeframe, while also providing an overview of the PKA’s responses to quality assurance. Study findings indicate a misalignment between institutional growth (11 to 39, 254.6% increase) and compliance with education quality, particularly in newly established programs. This study also advocates a more robust, competency-driven framework and continuous quality improvement mechanisms, as enhanced by the international standards to overcome the limitations of Poland’s current accreditation and quality assurance system in medical education. Specifically, to strengthen the institutional capacity of the accreditation body, it would be necessary to introduce the outcome-based evaluation that tracks graduate’s clinical competence, and institutional performance transparency through public reporting. This study emphasizes the critical need to align accreditation processes with national health workforce planning. This alignment is vital for establishing pathways for programs that may be underperforming in their capacity to produce a healthcare workforce that is adequately equipped for both purpose and practice across all regions.

1. Introduction

For many years, Poland has struggled with one of the lowest ratios of doctors per 1000 inhabitants among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. According to the latest Health at a Glance 2023 report, the situation is progressively improving, with the current ratio at 3.4 practicing doctors per 1000 population, compared to the OECD37 average of 3.7 (Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, 2023). According to the Statistics Poland (pol. Główny Urząd Statystyczny, GUS), a total of 158,902 doctors were practicing in Poland in 2022, of which 83% (131,400) were directly involved in patient care (Health and Health Care in 2022, 2023). However, recent data indicate a long-standing trend, with approximately 36% of medical doctors aged over 60 years old, and another 20% aged 50–59 (Health and Health Care in 2022, 2023). A persistent age gap in the physician workforce is also evident across numerous specialties (Kupis et al., 2025).

Medical education in Poland takes six years, after which graduates are required to complete a 13-month postgraduate internship and take the National Medical Final Exam (pol. Lekarski Egzamin Końcowy; LEK) to obtain full licensure to practice medicine (Michalik et al., 2024). Subsequently, depending on the graduate’s preference, they can either continue their education through residency training or work as a non-specialized physician, for instance, in primary care or an emergency department. To address workforce shortages, in addition to significantly expanded medical education over the past two decades, the Polish government has announced significantly higher enrolments to MD programs and master studies in the 2024/2025 academic year at 39 nationally accredited institutions, compared to previous years as per the new regulations which Ministry of Health has set for tuition free, state funded, or fee based and in a foreign language programs.

The large scale of expansion has challenged the capacity of national oversight bodies to ensure compliance with these standards, particularly for newer institutions that lack sufficient teaching infrastructure and academic staff as required by regulations. Numerous programs have been announced or launched at institutions with limited or no prior experience in clinical training (Dutczak, 2024; Kupis et al., 2025; Wójcik, 2025). This rapid expansion, reflective of the global trend of higher education massification, has exacerbated tensions between increased accessibility and the maintenance of educational quality (Gvaramadze, 2008; Marginson, 2016; Nyagope, 2023). This tension also closely aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4: Quality Education), which emphasizes inclusive and equitable access to education while ensuring learning outcomes and lifelong learning opportunities (García et al., 2020).

The national and international importance of this study is underscored by Poland’s membership in the European Union (EU), which entails a commitment to Directive 2005/36/EC established by the European Parliament and Council concerning the recognition of professional qualifications. By aligning with EU regulations, Poland ensures the automatic recognition of its medical degrees across the EU, thereby fostering greater cross-border mobility for physicians and enhancing collaboration within the healthcare sector, ultimately delivering mutual benefits to EU residents. The EU directive mandates harmonization of basic medical education across EU countries, including a minimum duration of six years of study or 5500 h of theoretical and practical training. Accreditation and quality assurance activities are conducted in alignment with the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG 2015), endorsed by the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA). The Polish Accreditation Committee (Polska Komisja Akredytacyjna, PKA) began its operations on 1 January 2002, under the name Państwowa Komisja Akredytacyjna (State Accreditation Committee). PKA was established as an independent body responsible for evaluating the quality of education in Polish higher education institutions, pursuant to the Act of 20 July 2001, amending the Act on Higher Education, the Act on Higher Vocational Schools, and certain other acts (Journal of Laws 2001, No. 85, item 924). In 2011, following a legislative amendment, the Committee was renamed to its current title–Polish Accreditation Committee. Its activities are currently governed by the Act of 20 July 2018- Law on Higher Education and Science (Journal of Laws 2023, item 742, as amended), which defines its structure, competencies, and operational procedures (Act of 20 July 2018. The Law on Higher Education and Science. [Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lipca 2018 r.–Prawo o Szkolnictwie Wyższym i Nauce], 2018; The Polish Accreditation Committee, 2025). The PKA’s core mandate is to uphold educational standards in line with European and global best practices and to support both public and private universities in their continuous quality enhancement efforts. The Committee conducts structured and mandatory evaluations of both newly established and long-standing MD programs. It also issues recommendations regarding the authorization of new study programs. New programs are evaluated at three key milestones: after the first year, the third year, and upon completion of the first full cycle of education. Established programs undergo periodic evaluations, typically prior to the expiration of their previous accreditation period. Additionally, ad hoc evaluations may be initiated by the Minister of Education and Science when necessary The framework for these evaluations is specified in the Regulation of the Minister of Science and Higher Education of 12 September 2018, on Program Evaluation Criteria (Journal of Laws 2018, item 1787) (Act of 20 July 2018. The Law on Higher Education and Science. [Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lipca 2018 r.–Prawo o Szkolnictwie Wyższym i Nauce], 2018). The growing number of institutions and study programs has placed increasing pressure on the PKA. While accreditation is a foundational component of medical education globally, existing literature emphasizes the need to evolve beyond traditional input-based models toward systems emphasizing graduate competencies and continuous improvement (Frenk et al., 2010; Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, 2011; The World Federation for Medical Education, 2020).

In this context, the present study examines how effectively Poland’s accreditation system has been utilized to maintain educational quality amid the rapid expansion of higher medical institutions. The three main objectives of this paper are: to assess trends in the growth of freshmen admissions, and accredited institutions’ numbers offering MD education between 2004 and 2024, and to describe the quality assurance responses of the PKA. These analyses will help identify specific challenges and recommend targeted strategies for improving accreditation and quality assurance processes in Polish medical education.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a descriptive, document-based policy analysis approach, focusing on publicly available regulatory data and institutional records aquired from the PKA and the Medical Workforce Development Department of the Ministry of Health (MoH) (pol. Departament Rozwoju Kadr Medycznych) (Bowen, 2009; Gilson, 2012). It focused on examining structural changes in Polish medical education between 2004 and 2024, with particular attention to trends in student admissions, institutional growth, and the accreditation activities conducted by the PKA. Indicators of medical education expansion included the number of accredited institutions offering MD programs and annual admission quotas. Accreditation-related indicators encompassed the frequency of program evaluations conducted by the PKA, and the proportion of programs receiving positive evaluations in the academic year.

2.1. Data Collection

In September 2024, formal written requests for data and information were submitted to two national institutions: The MoH and subsequently the PKA. These inquiries sought detailed information about admission trends, institutional growth, and accreditation procedures in medical education over two decades (2004–2024). Additional publicly accessible sources–including legal acts, statistical bulletins, and online archives–were reviewed to supplement the obtained data.

From the MoH, information was collected on annual admission quotas to MD programs and the number of accredited institutions between 2004 and 2024. Additionally, data were gathered on the policies governing entry thresholds for medical education, the accreditation procedures applied to institutions, the mechanisms used to evaluate program quality, and the entities responsible for setting accreditation and evaluation criteria.

Complementary data from the PKA provided insight into the scope and frequency of program evaluations focused on the accreditation crisis. This included routine, requested, and ad hoc assessments, the share of evaluations resulting in positive accreditation outcomes, and the most frequently cited areas requiring improvement. Furthermore, the PKA’s current accreditation framework and assessment criteria were reviewed to better understand how institutional performance is measured and judged within the national quality assurance system. Together, these sources provide a nuanced understanding of how Poland has attempted to balance rapid educational expansion with the maintenance of high academic standards in medical training.

2.2. Data Analysis

This study adopts a descriptive, document-based policy analysis approach, focusing on publicly available regulatory data and institutional records acquired from the PKA and the MoH (Bowen, 2009; Gilson, 2012). It was applied to summarize frequency distributions and time-series trends in the number of institutions and admission quotas at the country level. To assess changes over time, two trend indices were applied. A Base Index was used to measure the cumulative growth in the number of institutions and admissions relative to the 2004/2005 academic year. A line index captured year-over-year fluctuations, enabling the identification of key inflection points in system expansion. The document analysis was primarily interpretive and descriptive in nature, relying on a close reading of responses from the Moh and PKA, policy texts, accreditation reports, and regulatory documents to identify patterns and system-level responses to educational massification. No formal qualitative analysis was conducted. The aim was to generate a system-wide overview of how the accreditation process has adapted–or failed to adapt–to the rapid growth in medical education provision over the past two decades.

3. Results

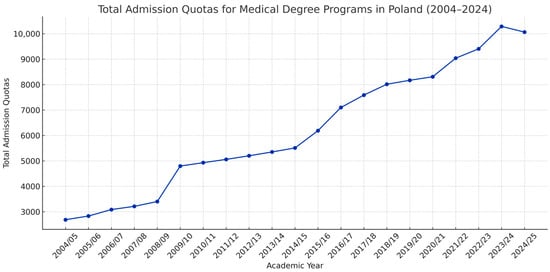

3.1. Trends in Admissions Quotas

Between the 2004/2005 and 2024/2025 academic years, the total number of admission slots for medical (MD) programs in Poland increased from 2688 to 10,065, representing an overall growth of 274.4%. For 2024/2025 this includes 6574 students in full-time, Polish-taught integrated master’s programs (tuition-free, state-funded), 1652 in Polish-taught integrated master’s programs (fee-based), and 1839 in master’s programs taught in a foreign language. The Base Index of enrolments for 2024/2025 was 374.4, indicating that the number of admissions has nearly quadrupled relative to the base year 2004/2005. The most significant expansion occurred in full-time, tuition-free, Polish-taught MD programs, where the number of available slots grew from 2240 to 6574. Additional growth was observed in fee-based Polish-language programs, which accounted for 1652 slots in 2024/2025, and in English-language programs, introduced in the 2009/2010 academic year, which expanded from 1219 to 1839 places over the analyzed period. Growth was not evenly distributed over time. In the first stage, between 2004 and 2010, the number of admission slots increased by 83.4%, corresponding to a line index of 183.4 for 2010/2011 relative to 2004/2005. Between 2010 and 2015, the growth slowed, reaching 29% (line index of 126.0 for 2015/2016 relative to 2010/2011). From 2015 to 2020, enrolments increased by a further 34.3% (index of 134.3 for 2020/2021 relative to 2015/2016), and between 2020 and 2024, the growth reached 21.1% (index of 121.1 for 2024/2025 relative to 2020/2021). However, a slight decline was observed between the 2023/2024 and 2024/2025 academic years, with a line index of 97.8 for 2024/2025 relative to 2023/2024, indicating a decrease of 2.2%. Despite this recent decline, the overall trend reflects a substantial and sustained increase in admission quotas over the past two decades. The most pronounced and accelerated growth occurred after 2015, following regulatory changes that allowed private universities to establish medical faculties. This significantly contributed to the rise in enrolment capacity in the second half of the analyzed period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total admission quotas for medical degree programs in Poland (2004–2024). This figure illustrates the increase in the total number of student admission quotas for all MD programs in Poland between 2004 and 2024. The most substantial growth occurred after 2015, coinciding with the rise of private medical education institutions.

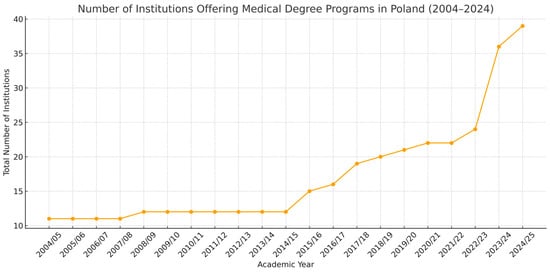

3.2. Institutional Growth

Between the 2004/2005 and 2023/2024 academic years, the number of institutions offering medical education in Poland expanded from 11 public universities to a total of 39 providers. The entry of private institutions began in 2015 and intensified after 2020, with over 30% of current medical education providers established within the last three years. This growth is reflected in the Base Index of the number of MD program providers, which reached 354.6 in the 2024/2025 academic year, representing a 254.6% increase from the 2004/2005 academic year. The line index of institutions confirms a trend of accelerating expansion: 9.1% from 2004 to 2010 (index: 109.1), 25% from 2010 to 2015 (index: 125.0), 46.7% from 2015 to 2020 (index: 146.7), and a striking 77.3% from 2020 to 2024 (index: 177.3). The pace of institutional growth has accelerated more than eightfold over two decades (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of institutions offering medical degree programs in Poland (2004–2024). This figure presents the number of institutions offering MD programs in Poland over two decades, with a notable acceleration in the establishment of new faculties after 2015.

3.3. Accreditation Activities of the PKA

Since 8 September 2005, and up to 6 March 2025, the PKA conducted a total of 92 evaluations of medical programs across Poland. Out of these, seven evaluations resulted in a negative outcome. The first program to receive a negative assessment was the Kazimierz Pułaski University of Technology and Humanities in Radom on 10 October 2019. The second was Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw. Notably, all five remaining negative decisions were issued in 2024, following formal requests from the Minister of Health, who initiated targeted inspections of institutions suspected of not meeting accreditation standards. Between 2020 and 2024, the PKA conducted 10 program evaluations directly at the request of the Minister, primarily targeting newly established institutions with limited teaching infrastructure and faculty capacity. These evaluations included: Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, President Stanisław Wojciechowski University in Kalisz, WSB Academy in Dąbrowa Górnicza, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Bielsko-Biała branch, Academy of Applied Sciences in Nowy Sącz, Social Academy of Sciences in Łódź, Academy of Applied Sciences in Nowy Targ, University of Siedlce, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Academy of Applied Sciences named after Prince Mieszko I in Poznań. While the closure or suspension of programs following negative evaluations is a necessary step to safeguard educational quality, it also raises critical questions about accessibility, equity, and the broader impact on healthcare workforce planning. The affected institutions were often located in regions with limited access to medical education and relied on to produce new cohorts of physicians. It remains unclear how many students were enrolled in these programs, what measures have been taken to secure the continuation of their training, and what consequences these decisions may have on local healthcare systems that may have depended on partnerships with these universities. Moreover, the extent to which such closures might undermine national efforts to alleviate physician shortages, especially in underserved regions, requires careful consideration. As comprehensive data on transfer policies, and institutional healthcare linkages are currently lacking, these issues will be revisited in the discussion section as part of this study’s limitations.

As a result of program evaluations conducted in 2024, a noteworthy regulatory development in 2024 was the introduction of “zero quotas” for institutions not meeting the accreditation criteria. According to the Minister of Health’s ordinance of 16 July 2024 (Journal of Laws of 2024, item 1085) and its 25 September 2024, amendment (Journal of Laws of 2024, item 1419), 39 institutions were authorized to admit students to MD programs, yet for six of them the admission limits were set to zero across all modes of study (e.g., Polish-language, English-language, full-time, part-time). A move largely attributed to negative or pending accreditation outcomes as well as insufficient teaching capacity identified by the PKA. This “zero quota” mechanism reveals a new layer of regulatory discretion in managing the quality and expansion of medical education. Rather than removing institutions entirely from the official list, the Ministry of Health maintains their presence in legislation while de facto blocking their recruitment through quota restriction.

4. Discussion

The increase in admission quotas and the expansion of medical education providers reflect Poland’s response to the longstanding health workforce shortages (Guziak et al., 2025). Between 2004 and 2024, the number of medical schools tripled, and student admissions quadrupled. Historically, in 2009, it shifted toward internationalization, marked by the introduction of programs taught in languages other than Polish and the establishment of private institutions offering medical programs in 2016. While this expansion aimed to address systemic gaps, it has simultaneously raised critical concerns about educational quality and accreditation capacity. In the context of the growth in the number of Polish medical students, it is worth emphasizing that the increased enrolments to medical schools in Poland are mostly a result of opening new MD programs at universities, some of which had no prior experience in educating medical disciplines. Recent policy reforms- including legislative amendments enabled occupational higher education institutions to offer MD programs. As Kupis et al. (2025) observe, these reforms resulted in a dramatic rise in new MD programs, many of which were approved despite receiving negative assessments from the PKA (Kupis et al., 2025). Their findings align with our data, which show that one-third of current MD providers were launched within the past three years, often without adequate teaching infrastructure or academic personnel. In response to growing quality concerns, the PKA has taken important steps, such as denying admission quotas to five institutions in 2024. However, these are reactive interventions. As demonstrated by the WHO and European regulatory bodies, sustainable quality assurance requires proactive, systemic strategies. These include real-time data monitoring, integration of graduate performance metrics (e.g., LEK pass rates), and risk-based accreditation models that differentiate between mature and emerging institutions (European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, 2016; Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, 2022; World Health Organization, 2021). Polish academic leaders and stakeholders have voiced the need for robust audits and corrective measures within the accreditation system (Grzela, 2024; Puls Medycyny, 2024). In response, the Minister of Science and Higher Education announced that institutions failing to meet educational standards during inspections would face closure, with affected students given the opportunity to transfer to other universities (Polish Press Agency, 2024). However, to date, no institution has been formally closed as a result of these declarations, and the proposed transfer mechanisms have not been implemented in practice.

Kupis et al. further emphasize a troubling legislative inconsistency: while PKA’s assessments identify serious quality deficits, the Ministry retains final authority to approve programs, leading to the proliferation of inadequately prepared providers. This disconnect undermines the authority of accreditation bodies and signals the need for stronger integration of expert recommendations into binding decisions (Kupis et al., 2025). The Polish Academia advocate for strengthening the PKA’s capacity to conduct thorough evaluations and enhancing transparency in accreditation outcomes to guide improvement efforts. They have also stressed the necessity of closing programs that fail to meet national standards (Grzela, 2024; Polish Press Agency, 2024). From a comparative perspective, insights from Serbia suggest that external frameworks–such as the WHO National Health Workforce Accounts (NHWA)–can provide valuable benchmarks for aligning accreditation with national health priorities. Serbian accreditation standards, for instance, focused on structural and academic quality, they underemphasized social accountability and alignment with population health needs, dimensions also absent from Polish accreditation mechanisms. In both countries, accreditation models remain input-focused and insufficiently adapted to outcome-based or context-sensitive evaluation (Buljugic & Milicevic, 2021). Finally, Poland must avoid the trap of quantity-driven expansion at the expense of systemic coherence. Massification without mechanisms for quality assurance can produce degrees with diminished social and economic value (Altbach et al., 2009). If Poland’s reforms are to be sustainable, accreditation must evolve from a procedural requirement into a strategic instrument for aligning medical education with societal needs. Beyond the structural recommendations, we argue that greater alignment is also needed between accreditation outcomes and workforce planning. Currently, the accreditation process is largely disconnected from national human resource for health policy. Future reform could integrate NHWA indicators into accreditation procedures, ensuring that institutions not only meet academic criteria but also contribute meaningfully to addressing geographic and specialty-specific shortages (Guziak et al., 2025). Moreover, the lack of transparent, centralized reporting of accreditation outcomes remains a critical weakness. While PKA reports are formally public, they are scattered across separate documents, making comparative analysis difficult. Developing a unified, searchable database of accreditation results and institutional profiles could empower students, employers, and policymakers to make better-informed decisions. Finally, the current accreditation framework offers limited pathways for institutional remediation. In contrast to models in the Netherlands (Hillen, 2010) and Canada (Blouin & Tekian, 2018), which offer guided improvement plans and follow-up reviews, the Polish model leans heavily on punitive measures, such as revoking quotas. Embedding constructive, stepwise quality improvement pathways into the accreditation process could foster institutional learning rather than institutional failure.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is based primarily on publicly available documents and formal data obtained from national institutions, which may not fully capture informal practices or internal decision-making processes influencing accreditation activities. Second, while the analysis identifies trends in institutional growth and program evaluations, it lacks data on graduate placement and career trajectories for evaluating the effectiveness and social accountability of MD programs. Third, this study was unable to assess the immediate educational and clinical consequences of recent program closures, as comprehensive data on student transfer procedures, continuity of training, and the impact on local healthcare delivery are currently unavailable. Finally, as a descriptive policy analysis, this study does not incorporate qualitative perspectives from key stakeholders, such as students, faculty members, or accreditation experts, which could offer valuable insights into the experiences and practical consequences of these reforms. In addition to the above, future studies should explore program outcomes such as graduation rates, LEK pass rates, and employment patterns of graduates, which would provide more powerful evidence of whether the rapid expansion of medical education has affected educational quality. Incorporating graduates’ perspectives on their training experiences, satisfaction with their education, and subsequent career trajectories, as well as employers’ satisfaction with graduates’ performance, would add valuable insights into the social accountability of MD programs. Furthermore, the integration of key performance indicators (KPIs) could help determine whether targeted learning outcomes are being achieved. A SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) thematic analysis might also be applied in future research to systematically identify areas for strategic development of Polish medical education. Finally, longitudinal monitoring and follow-up studies are necessary to assess not only the short-term accreditation outcomes but also the long-term effectiveness of policy reforms. By combining quantitative outcome measures with qualitative stakeholder perspectives, future research can contribute to a more outcome-oriented, competency-driven model of accreditation.

5. Conclusions

Poland’s ambitious expansion of medical education represents an essential step toward addressing healthcare workforce shortages. Between 2004 and 2024, the number of medical schools tripled, and student admissions quadrupled. However, in addition to global debate on the maintaining high educational standards the Polish MD programs require evolving accreditation model. This study findings underscore the critical need for comprehensive regional strategies to ensure that newly established and long-standing programs in Poland are capable of adequately preparing graduates for the medical career for the mutual benefits of patients in the EU member states. To that end, we propose five key reforms:

- Strengthening Accreditation Capacity: The PKA should receive increased institutional support–including staffing and legal authority–to manage the growing number of programs effectively.

- Outcome-Based Evaluation: Accreditation criteria should extend beyond formal compliance to include indicators of clinical competence, graduate tracking, and population health impact.

- Context-Sensitive Accreditation: Following the Serbian example, accreditation standards should better reflect local health system needs, especially in underserved regions (Buljugic & Milicevic, 2021).

- Public Transparency and Stakeholder Engagement: Making PKA evaluation reports fully accessible and involving professional bodies, students, and civil society in the accreditation process would enhance legitimacy and responsiveness.

- Remediation and Quality Improvement Pathways: Accreditation procedures should include structured, stepwise support for underperforming institutions–such as improvement plans and follow-up evaluations–mirroring the formative approaches used in the Netherlands and Canada (Blouin & Tekian, 2018; Hillen, 2010).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; Methodology, M.G. and M.Š.-M.; Formal analysis, M.G. and A.J.Ś.; Data curation, M.G.; Writing—original draft, M.G.; Writing—review & editing, M.G., A.J.Ś., and M.Š.-M.; Visualization, M.G. and A.J.Ś.; Supervision, M.Š.-M.; Project administration, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared within the framework of the project implemented by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, and the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Project Contract Number: 451-03-137/2025-03/200110). The author, Mateusz Guziak, wishes to acknowledge that this research was carried out during his internship at the Laboratory for Strengthening Capacity and Performance of Health Systems & Workforce for Health Equity, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Serbia. He also wishes to thank Elżbieta Gelert, Director General of the Provincial Integrated Hospital in Elbląg (pl. Wojewódzki Szpital Zespolony w Elblągu), and Hanicenta Rzepa, Coordinator of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, for their kind support in organizing the internship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| GUS | Statistics Poland (pol. Główny Urząd Statystyczny) |

| LEK | National Medical Final Exam (pol. Lekarski Egzamin Końcowy) |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

| PKA | Polish Accreditation Committee (pol. Polska Komisja Akredytacyjna) |

References

- Act of 20 July 2018. The law on higher education and science. [Ustawa z dnia 20 lipca 2018 r.–Prawo o szkolnictwie wyższym i nauce]. (2018). Dz.U. 2018 Poz. 1668. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180001668 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183219 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Blouin, D., & Tekian, A. (2018). Accreditation of medical education programs: Moving from student outcomes to continuous quality improvement measures. Academic Medicine, 93(3), 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljugic, B., & Milicevic, M. S. Analysis of accreditation standards for undergraduate medical studies in Serbia through the lens of the National Health Workforce Accounts. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-64019/v3 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Dutczak, R. (2024). Czarnek otworzył nowe kierunki medyczne niespełniające standardów. Pójście w „ilość” nie rozwiąże problem–Klub Jagielloński. Available online: https://klubjagiellonski.pl/2024/01/23/czarnek-otworzyl-nowe-kierunki-medyczne-niespelniajace-standardow-pojscie-w-ilosc-nie-rozwiaze-problemu/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education. (2016). Implementing and using quality assurance: Strategy and practice. ENQA. Available online: https://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2nd-Forum-Implement.-Using-QA_final-1.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D., & Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Ttransforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376(9756), 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, E. G., Magaña, E. C., & Ariza, A. C. (2020). Quality education as a sustainable development goal in the context of 2030 agenda: Bibliometric approach. Sustainability, 12(15), 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L. (2012). Health policy and systems research: A methodology reader. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44803 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Grzela, E. (2024). Czy nowe kierunki lekarskie pójdą pod ministerialny nóż? Uczelnie: Jesteśmy spokojni, wdrażamy działania naprawcze–Puls medycyny–Pulsmedycyny.Pl. Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/czy-nowe-kierunki-lekarskie-pojda-pod-ministerialny-noz-uczelnie-jestesmy-spokojni-wdrazamy-dzialania-naprawcze-1205820 (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Guziak, M., Walkiewicz, M., Nowicka-Sauer, K., & Šantrić-Milićević, M. (2025). Future research directions on physicians in Polish primary healthcare: Workforce challenges and policy considerations. Critical Public Health, 35(1), 2495687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvaramadze, I. (2008). From quality assurance to quality enhancement in the European higher education area. European Journal of Education, 43(4), 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and health care in 2022. (2023). Statistics Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Health at a glance 2023: OECD indicators. (2023). OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H. F. P. (2010). Quality assurance of medical education in the Netherlands: Programme or systems accreditation? Tijdschrift Voor Medisch Onderwijs, 29(1), 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupis, R., Perera, I., Domagała, A., & Szopa, M. (2025). Medical education in Poland: A descriptive analysis of legislative changes broadening the range of institutions eligible to conduct medical degree programmes. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marginson, S. (2016). High participation systems of higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, B., Kulbat, M., & Domagała, A. (2024). Factors affecting young doctors’ choice of medical specialty–A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 19(2), e0297927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyagope, T. S. (2023). Massification at higher education institutions; Challenges associated with teaching large classes and how it impacts the quality of teaching and learning. Al-Mudarris: Journal of Education, 6(2), 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Press Agency. (2024). Minister wieczorek zdradził, które nowe kierunki lekarskie będą zamykane. Available online: https://www.rynekzdrowia.pl/Nauka/Minister-Wieczorek-zdradzil-ktore-nowe-kierunki-lekarskie-beda-zamykane,256157,9.html (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Puls Medycyny. (2024, January 18). Kryzys specjalistów i lekarzy POZ. Zwiększa się dystans między Polską a innymi krajami OECD. Puls Medycyny. Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/kryzys-specjalistow-i-lekarzy-poz-zwieksza-sie-dystans-miedzy-polska-a-innymi-krajami-oecd-1205893#:~:text=Zwiększa%20się%20dystans%20między%20Polską%20a%20innymi%20krajami%20OECD,-AS&text=Według%20ostatniego%20raportu%20OECD%20„Health,OECD%20wynoszącej%209%2C2) (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. (2022). Data-driven, risk-based quality regulation. QAA. Available online: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/about-us/data-driven-quality-assessment-final.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Schuwirth, L. W. T., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2011). Programmatic assessment: From assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Medical Teacher, 33(6), 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Polish Accreditation Committee. (2025). Available online: https://pka.edu.pl/en/home-page/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- The World Federation for Medical Education. (2020). Basic medical education WFME global standards for quality improvement. Available online: www.wfme.org (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2021). WHO academy quality management framework. World Health Organization. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/who-academy-documents/final-quality-management-framework_with-evidence.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wójcik, P. (2025). Rezydenci pytają ministra nauki: Gdzie ta jakość kształcenia? Były zapowiedzi–Ustaw i rozporządzeń brak–MedExpress.pl. Available online: https://www.medexpress.pl/zawody-medyczne/rezydenci-pytaja-ministra-nauki-gdzie-ta-jakosc-ksztalcenia-byly-zapowiedzi-ustaw-i-rozporzadzen-brak/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).