Enhancing Heritage Education Through ICT: Insights from the H2OMap Erasmus+ Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. European STEM Framework

2.2. Context of the Study

2.3. Methodology

3. Results

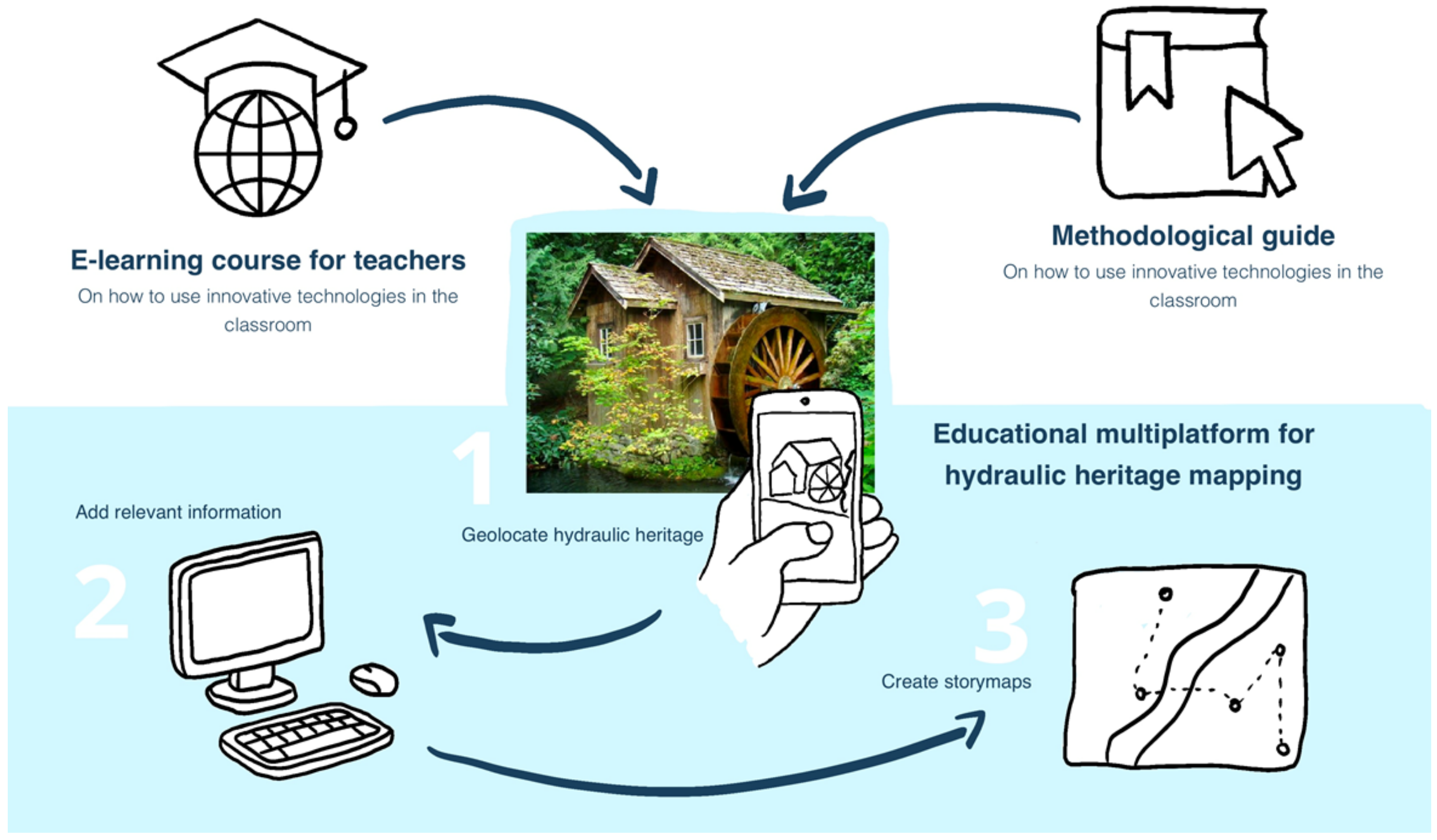

- IO1: Methodological GuideThe methodological guide1 provided a structured framework for integrating ICT into heritage education, enriched with case studies from Spain, Italy, and Portugal. From the analysis presented here, teachers valued the guide as a concrete resource for lesson planning, particularly in linking cultural heritage with curricular requirements in history, geography, and environmental studies. Its regionally adapted examples offered practical ways of situating digital activities within local contexts, which enhanced relevance and student interest. Moreover, the guide proved useful beyond the school environment: local authorities and cultural organisations reported that it served as a bridge between educational practice and community heritage initiatives. Taken together, IO1 enabled teachers to adopt ICT-supported, cross-curricular practice and strengthened collaboration between schools and external stakeholders.

- IO2: E-learning CoursesThe e-learning course2 trained teachers in the use of ICT tools through GIS-based systems, cartography development, spatial data models, heritage documentation workflows, and creation of StoryMaps, with a focus on embedding them into active learning methodologies. The evidence discussed in this paper shows that participants reported increased digital competence and greater confidence in implementing ICT within their teaching practice. Teachers particularly highlighted the usefulness of these tools for transforming history and geography into engaging, interactive, and practice-oriented subjects. By analysing their feedback, the article demonstrates how IO2 helped reduce the gap between students’ everyday digital fluency and the demands of curricular content. Furthermore, the courses provided a platform for teachers from different regions to exchange experiences, contributing to the creation of informal professional learning networks.

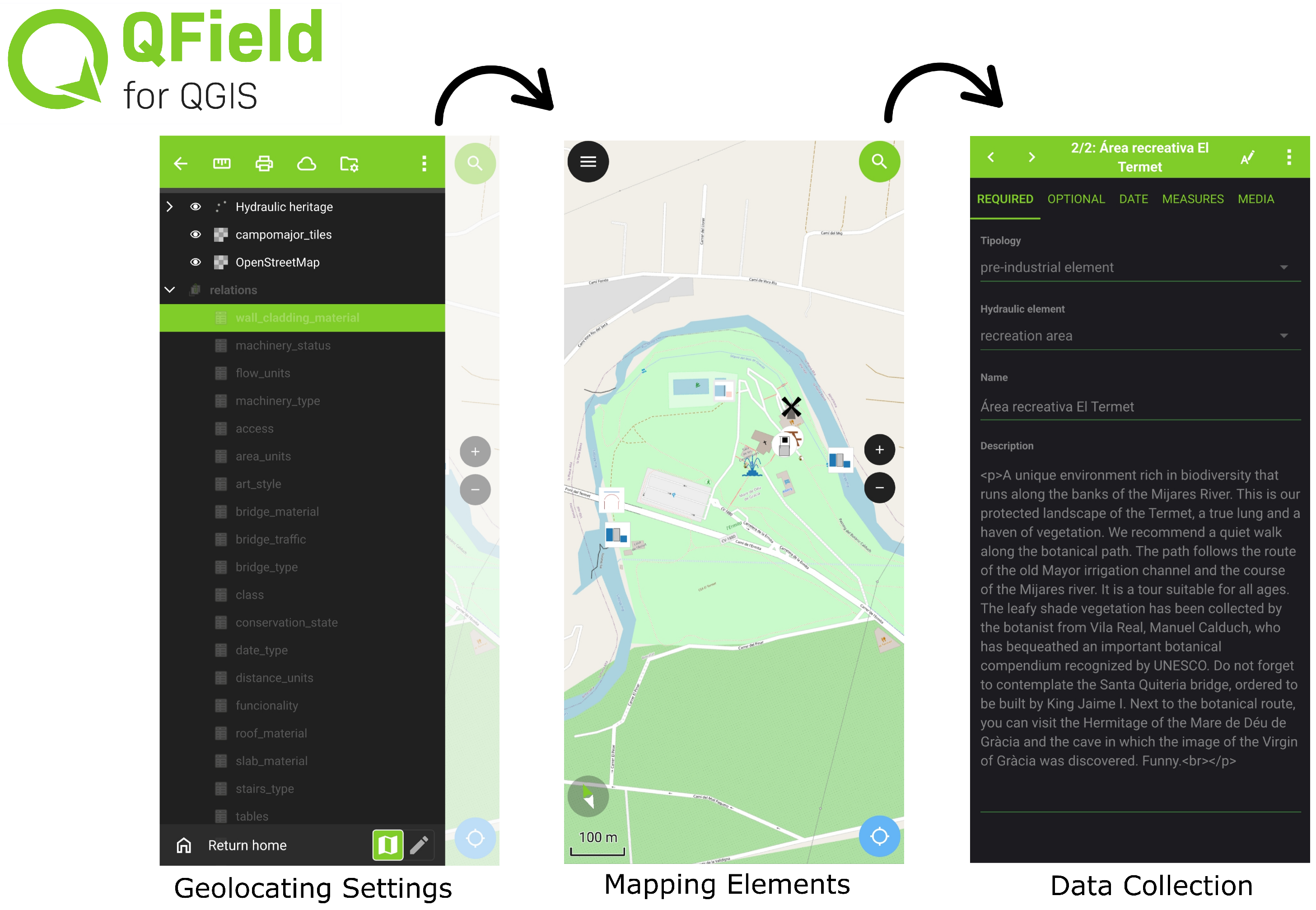

- IO3: Educational MultiplatformThe multiplatform system, consisting of a mobile application (Figure 2), an online database, and a geoportal, was evaluated in terms of its direct impact on teaching and learning practices. The mobile application allowed students to map more than 100 hydraulic heritage elements during fieldwork, linking digital skills with cultural knowledge. Teachers reported that these activities strengthen collaboration, encourage responsibility for the preservation of local resources, and provide a deeper sense of ownership over the learning process. The online database further extended these outcomes by enabling students to curate and interpret georeferenced data, enhancing their data literacy and research competences. Finally, the geoportal and its interactive StoryMaps allowed both teachers and students to visualise heritage elements within broader historical and geographical narratives. This resource helped to connect individual observations with systemic patterns, deepening conceptual understanding while making heritage more tangible and accessible. In the analysis, IO3 is presented as a model of how ICT can be used to create participatory, interdisciplinary, and socially relevant learning environments.The three intellectual outputs provide evidence that the integration of ICT in heritage education yields outcomes that extend beyond technological innovation. The work highlights how these tools support teachers in acquiring digital competences, enable students to engage actively with their cultural environment, and promote networks between schools, universities, and local communities. These results demonstrate that ICT can enhance not only the technical dimension of education but also its capacity to connect learning with lived experience, strengthen civic responsibility, and support sustainability.

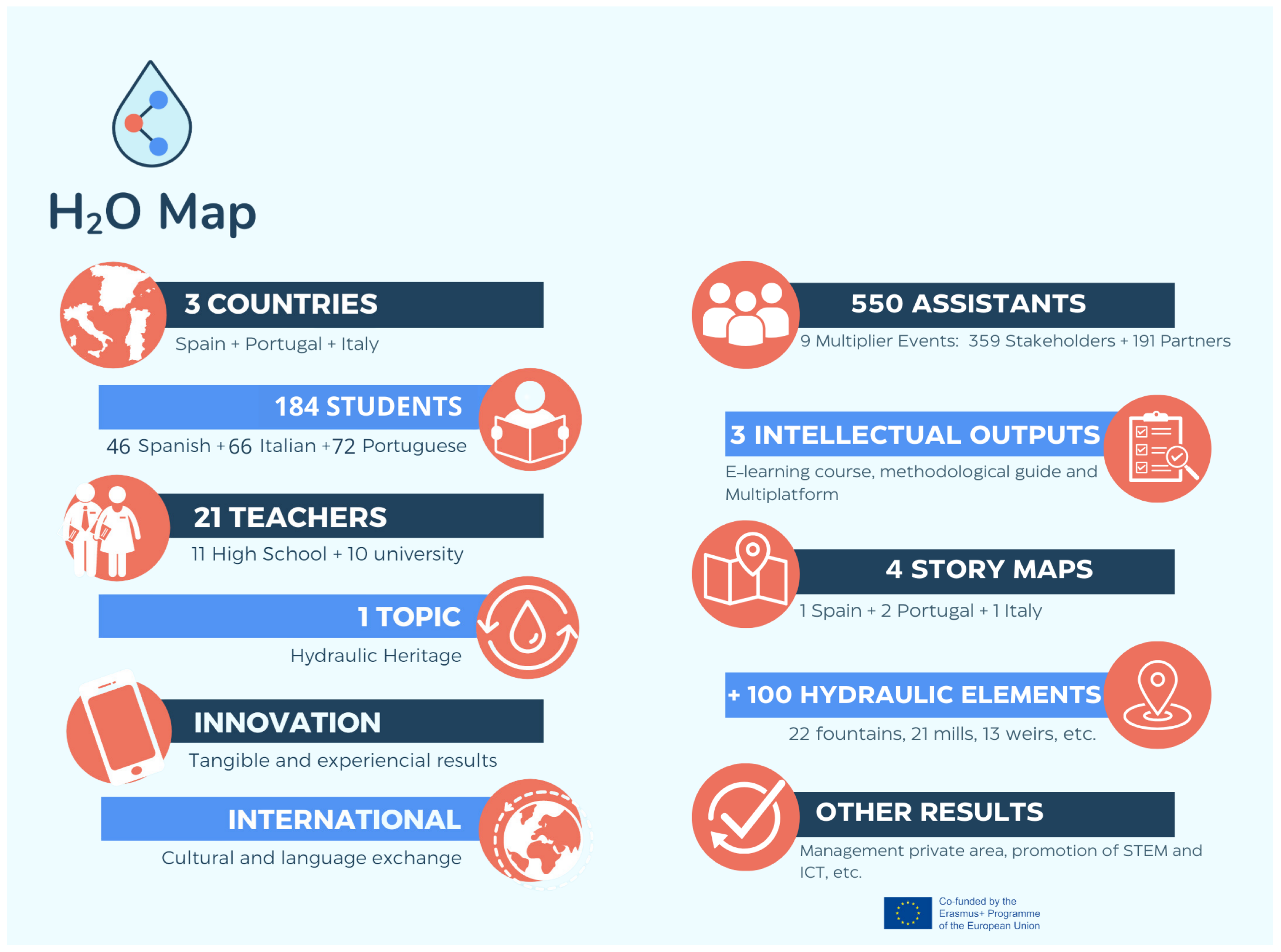

- IR1: The teachers in the participating high schools learned to use new educational tools. Although 11 teachers were permanently linked to the project, a total of 24 were initially planned to participate across the different activities throughout its duration. By the end of the project, however, the number increased to 35, representing a 45.8% growth compared to the expected 24. In addition, two schools implemented activities to promote these tools more widely within their centers, enabling additional teachers to adopt them in their own classrooms, thereby supporting STEM through interdisciplinary education. Since all materials were designed as open access, the initiative can be readily adopted by schools beyond the project partnership, as evidenced by downloads of the methodological guides in different languages (English: 213; Italian: 66; Portuguese: 50; and Spanish: 61). Moreover, the open-access e-learning courses uploaded to YouTube have received an average of 22 views per video, further extending the project’s reach.

- IR2: The students from the participating high schools strengthened their ICT and STEM skills, facilitating their future integration into the labour market. Interest in the knowledge and use of the tools is evident in the fact that, although the project design initially considered 10 students per school (a total of 120 across the three mobility programmes for field testing, aged 14–16 years), the actual number of students who participated in the activities reached 184. Analysis of the completed fields shows that the most frequently and consistently filled field was the image upload, reflecting strong student engagement with visual documentation. This tendency aligns with the findings of Ponsoda-López de Atalaya et al. (2023), who observes that, as in this project, students often state that “Using photographs in the classroom leads to increased motivation and interest among students, since the visual aspect of the images is more intriguing than any other resource.”

- IR3: Both students and teachers participating in the project (more than 200 people) acquired new sensitivity regarding the social and educational value of historical hydraulic heritage, reinforcing their civic responsibility to safeguard it. This interest in the preservation of hydraulic heritage—both for its historical dimension and as a key component of the ecosystem—was particularly evident in interviews conducted after field activities. For example, in response to the question “Why is water important?”, one student reflected: “The most impressive thing that we have done during this journey is the route inside nature that helped us to discover and learn the importance of all the water inside the ecosystem.” Similarly, when asked to highlight a heritage element in their city, participants frequently emphasised the adaptive uses of these infrastructures across different eras, shifting from work-related purposes in the past to tourism boosters today: “In our city there is a river and artificial canals; in ancient times they were important for merchants and commerce, and now they are important for tourism and water sports.”This new awareness was not limited to direct participants but was also transferred to more than 550 additional attendees engaged in dissemination events (such as the nine Multiplier Events), broadening the project’s impact on heritage appreciation and conservation attitudes within local communities; Figure 3.

- IR4: Finally, this project effectively facilitated collaboration, mobility, innovation, and the establishment of enduring networks and partnerships among European educational institutions. These achievements have significantly enriched the educational experience and contributed to the personal and professional growth of participants. During the project, eight virtual meetings were held for continuous monitoring and planning of actions, complemented by six previously scheduled transnational meetings, plus an additional closing meeting to reinforce alliances in view of future European project proposals. To strengthen this network of stakeholders interested in preserving heritage through the use of ICT tools, joint actions were carried out between secondary schools, while universities integrated the project’s themes into their summer schools, using hydraulic heritage as a starting point to reflect on the construction of more sustainable cities. Moreover, the collaborative relationships developed between project partners and municipalities have supported local development and encouraged active citizenship among young people.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Research Ethics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| HH | Hydraulic Heritage |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| 1 | https://h2omap.uji.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Guida-EN.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025). |

| 2 | https://h2omap.uji.es/e-learning-course/ (accessed on 3 August 2025). |

References

- Ávila-Ruiz, R. M. (2005). Reflexiones sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del patrimonio integrado. una experiencia en la formación de maestros. Investigación en La Escuela, 56, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A., de Bustamante, I., & Pascual-Aguilar, J. A. (2019). Using old cartography for the inventory of a forgotten heritage: The hydraulic heritage of the community of madrid. Science of the Total Environment, 665, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzelli, G., Raia, A., Ricciardi, S., Nino, M. D., Barile, N., Perrella, M., Tramontano, M., Pagano, A., & Palombini, A. (2019). An integrated Vr/Ar framework for user-centric interactive experience of cultural heritage: The arkaeVision project. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 15, e00124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G., & Weber, D. (2012). Measuring change in place values using public participation GIS (PPGIS). Applied Geography, 34, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, D., Meng, Y., Deng, C., Li, Q., & Chaudhary, S. (2024). Digitalizing cultural heritage through metaverse applications: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Heritage Science, 12(1), 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, G., Escobar, P., Carrasco, R. C., & Marco-Such, M. (2019). A linked open data framework to enhance the discoverability and impact of culture heritage. Journal of Information Science, 45(6), 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Calviño, L., Rodríguez-Medina, J., & López-Facal, R. (2020). Heritage education under evaluation: The usefulness, efficiency and effectiveness of heritage education programmes. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catana, M. M., & Brilha, J. B. (2020). The role of unesco global geoparks in promoting geosciences education for sustainability. Geoheritage, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenor, J., & Ma, M. (2019). A review of augmented reality applications for history education and heritage visualisation. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 3(2), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, K., Hetherington, L., Juillard, S., Aguirre, C., & Duca, E. (2025). A framework for effective STEAM education: Pedagogy for responding to wicked problems. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 9, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, D., Angelini, M. G., Alfio, V. S., Claveri, M., & Settembrini, F. (2020). Implementation of a system WebGIS open-source for the protection and sustainable management of rural heritage. Applied Geomatics, 12, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-López, J. M., Martín-Cáceres, M. J., & Estepa-Giménez, J. (2021). Teacher training in heritage education: Good practices for citizenship education. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Puente, J. M., Montero, A. C., & Carmenado, I. D. L. R. (2009). Empowering communities through evaluation: Some lessons from rural Spain. Community Development Journal, 44, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorsselaere, J. V. (2021). Connecting sustainable development and heritage education? An analysis of the curriculum reform in flemish public secondary schools. Sustainability, 13, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B., Frasch, T., & Jeyacheya, J. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of land-use zoning for the protection of built heritage in the bagan archaeological zone, myanmar—A satellite remote-sensing approach. Land Use Policy, 88, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estepa, J. (2009, March 31–April 3). La educación del patrimonio y la ciudadanía europea en el contexto Español. L’educazione alla Cittadinanza Europea e la Formazione Degli Insegnanti. Un progetto educativo per la “Strategia di Lisbona”: Atti XX Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. I Convegno Internazionale Italo-Spagnolo di Didattica delle Scienze Sociali, Bologna, Pàtron. [Google Scholar]

- Estepa-Giménez, J., & Delgado-Algarra, E. J. (2021). Educación ciudadana, patrimonio y memoria en la enseñanza de la historia: Estudio de caso e investigación-acción en la formación inicial del profesorado de secundaria||Citizenship education, heritage and memory in the teaching of history: Case study and action research in the initial training of High School Education teachers. REIDICS. Revista De Investigación En Didáctica De Las Ciencias Sociales, 8, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2025). Communication: A stem education strategic plan: Skills for competitiveness and innovation (COM(2025) 89 final) (Tech. Rep.). Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/document/stem-education-strategic-plan-legal-document (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Fagerholm, N., Käyhkö, N., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2013). Landscape characterization integrating expert and local spatial knowledge of land and forest resources. Environmental Management, 52, 660–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felices de la Fuente, M. d. M., Chaparro-Sainz, Á., & Rodríguez-Pérez, R. A. (2020). Perceptions on the use of heritage to teach history in secondary education teachers in training. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, R., & Bru, J. (2017). Ambiente, territorio y paisaje valores y valoraciones. Available online: https://www.editorialbarcino.cat/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- García-Esparza, J. A., Altaba Tena, P., & Valentín, A. (2023). An interdisciplinary secondary school didactic unit based on local natural and cultural heritage. Heritage & Society, 17(2), 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M. F. (2007). Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography (Vol. 69). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P., & Nolan, K. (1999). A critical analysis of research in environmental education. Studies in Science Education, 34, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J., & Iranzo, E. (2014). Claves geográficas para la interpretación del patrimonio hidráulico mediterráneo. A propósito de los regadíos históricos valencianos. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 66, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS: International Council on Monuments and Sites. (2019). Engaging cultural heritage in climate action outline of climate change and cultural heritage. ICOMOS: International Council on Monuments and Sites. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, M., & Pachler, N. (2013). Learning to teach using ict in the secondary school: A companion to school experience. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., & Zhang, B. (2017). Identification of landscape character types for trans-regional integration in the wuling mountain multi-ethnic area of southwest china. Landscape and Urban Planning, 162, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, D., & Abrahams, R. (2019). Mediating urban transition through rural tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 75, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. (2015). The past is a foreign country–Revisited (pp. 639–660). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- López, J. M. C. (2016). Escuela, patrimonio sociedad. In La Socialización Del Patrimonio. UNES, Universidad, Escuela y Sociedad. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bravo, C., López, J. P., & Adell, E. M. (2022). The Management of water heritage in portuguese cities: Recent regeneration projects in évora, lisbon, braga and guimarães. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 11, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malegiannaki, I., & Daradoumis, T. (2017). Analyzing the educational design, use and effect of spatial games for cultural heritage: A literature review. Computers and Education, 108, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, F. (2006). Introduction: Heritage and identity (Vol. 12). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación. (2015). Plan nacional de educación y patrimonio. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/dam/jcr:a91981e8-8763-446b-be14-fe0080777d12/12-maquetado-educacion-patrimonio.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Miralles, P., Gómez, C., & Rodríguez, R. (2017). Patrimonio, competencias históricas y metodologías activas de aprendizaje. un análisis de las opiniones de los docentes en formación en españa e inglaterra. Estudios Pedagógicos, 43(4), 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Y. (2018). La participación ciudadana en la conservación del patrimonio. Las asociaciones locales como fenómeno emergente. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10498/23197 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A. M., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2023). Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 373–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, K. R. (2016). Performing on the landscape versus doing landscape: Perambulatory practice, sight and the sense of belonging. In Ways of walking. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ponsoda-López de Atalaya, S., Blanes-Mora, R., & Moreno-Vera, J. R. (2023). The photographic heritage as a motivational resource to learn and teach history. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1270851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B., Gonçalves, J., Martins, A. M., Pérez-Cano, M. T., Mosquera-Adell, E., Dimelli, D., Lagarias, A., & Almeida, P. G. (2021). GIS in architectural teaching and research: Planning and heritage. Education Sciences, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoolnet, E. (2018). Science, technology, engineering and mathematics education policies in europe. Scientix observatory report (Tech. Rep.). Available online: http://www.scientix.eu (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Silverman, H. (2011). Contested cultural heritage: A selective historiography (pp. 1–49). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T., Halvorsen, R., & Erikstad, L. (2018). Methods for landscape characterisation and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strano, A., Mariani, J., Alhoud, A., & Kittler, N. (2021). How to communicate your project—A step-by-step guide on communicating projects and their results. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasbourg: Council of Europe. (2000). European landscape convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/the-european-landscape-convention (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Tempesta, T. (2010). The perception of agrarian historical landscapes: A study of the veneto plain in italy. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnpenny, M. (2004). Cultural heritage, an ill-defined concept? A call for joined-up policy. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 10, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2005). The 2005 convention on the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2022). Basic texts of the 2003 convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage 2022 edition. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development preamble. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. (2010). A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, D., & Makri, A. (2019). Online communication and interaction in distance higher education: A framework study of good practice. International Review of Education, 65, 605–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlami, V., Kokkoris, I. P., Zogaris, S., Cartalis, C., Kehayias, G., & Dimopoulos, P. (2017). Cultural landscapes and attributes of “culturalness” in protected areas: An exploratory assessment in greece. Science of the Total Environment, 595, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B., Dai, L., & Liao, B. (2023). System architecture design of a multimedia platform to increase awareness of cultural heritage: A case study of sustainable cultural heritage. Sustainability, 15, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemini, M., Engel, L., & Simon, A. B. (2025). Place-based education—A systematic review of literature (Vol. 77). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trifi, D.; Altaba, P.; Barreda-Juan, P.; Monrós-Andreu, G.; Menéndez, L.; García-Esparza, J.A.; Chiva, S. Enhancing Heritage Education Through ICT: Insights from the H2OMap Erasmus+ Project. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091164

Trifi D, Altaba P, Barreda-Juan P, Monrós-Andreu G, Menéndez L, García-Esparza JA, Chiva S. Enhancing Heritage Education Through ICT: Insights from the H2OMap Erasmus+ Project. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091164

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrifi, Delia, Pablo Altaba, Paloma Barreda-Juan, Guillem Monrós-Andreu, Laura Menéndez, Juan A. García-Esparza, and Sergio Chiva. 2025. "Enhancing Heritage Education Through ICT: Insights from the H2OMap Erasmus+ Project" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091164

APA StyleTrifi, D., Altaba, P., Barreda-Juan, P., Monrós-Andreu, G., Menéndez, L., García-Esparza, J. A., & Chiva, S. (2025). Enhancing Heritage Education Through ICT: Insights from the H2OMap Erasmus+ Project. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091164