Abstract

Educator agency in the form of choice over learning experiences is widely thought to enhance educator engagement and instructional improvement, yet causal evidence is scarce. We conducted a preregistered randomized controlled trial in an online computer science course with volunteer instructors who teach students worldwide. All instructors (N = 583) received automated feedback on their instruction, with half randomly assigned to have choice over the feedback topic. Choice alone did not increase feedback engagement or yield observable changes in practice, but it raised student attendance—an effect that was strongest for instructors who voluntarily engaged with additional training resources, including training modules and teaching simulations. For this subset of instructors, having choice over feedback had significant positive impacts on their instruction and student outcomes compared to the control group. This suggests that agency in choosing feedback topics may be most effective when combined with instructors’ intrinsic motivation to pursue self-directed improvement. Our study also demonstrates a scalable method for testing design principles in educator training and underscores the need to examine when, how and for whom agency might drive improvement.

1. Introduction

Allowing educators agency in choosing their learning experiences is thought to promote engagement and changes in practice (Calvert, 2016; Diaz-Maggioli, 2004; Lieberman & Pointer Mace, 2008; Smith, 2017, inter alia). Advantages of allowing educators choice include the potential for better alignment with their needs, enhanced engagement, and increased follow-through (Kennedy, 2016b). Weaving educator choice into learning opportunities has been endorsed by many leading scholars in the field of education (Carter Andrews & Richmond, 2019; Zeichner, 2019), and has also been embedded in common coaching and professional learning community protocols, for instance, when educators choose their own focus of improvement or topic of collegial inquiry.

However, educators often lack input into and/or choice over the content of their learning. In K-12 settings, teachers report having only partial control over their professional development opportunities (Doan et al., 2021). In many higher education settings, instructors participate in required training prior to beginning their teaching (e.g., Chadha, 2013; Slaughter et al., 2023). States often require preK teachers to complete training in child development, family relationships, and health and safety (e.g., Weisenfeld et al., 2023). Even in K-12 professional learning communities—typically school-based teams of teachers working collaboratively to meet their students’ needs—choice over learning content is present only about half the time (Zuo et al., 2023). Furthermore, providing educators choices about their professional learning often conflicts with prevalent policy approaches that “diagnose” problems with instruction and apply prescribed “solutions” through teacher opportunities to learn (Biesta et al., 2015)—an approach that remains the dominant form of instructional improvement in many Western nations today.

Remarkably, despite the widespread belief that providing educators agency in choosing the topics for their learning matters, there exists little empirical evidence on the topic. The evidence that does exist consists largely of illustrative cases or relies mainly on teacher self-reports (Brodie, 2021; Chadha, 2013; Martin et al., 2019; Philpott & Oates, 2017), rather than carefully controlled comparative or randomized studies with a range of self-report, behavioral, and student outcomes. To address this gap, we conducted a preregistered randomized controlled trial investigating whether allowing instructors in an online course to choose the type of feedback they receive affects their engagement with that feedback, their instructional practices, and student outcomes. Specifically, our study sought to answer the following research questions:

- Does providing instructors choice over feedback impact their engagement with the feedback, their perception of the feedback, or their teaching practice?

- Does choice over feedback for instructors impact their students’ outcomes?

- How do treatment effects vary by instructor demographics and whether the instructor engages with self-directed training beyond automated feedback (i.e., training modules, teaching simulations)?

We conducted this randomized controlled trial within Code in Place, a free online introductory programming course with volunteer instructors who teach students worldwide. All instructors (N = 583) received automated feedback on their teaching based on natural language processing analysis of their section recordings. We randomly assigned instructors to the treatment or control group. Those in the treatment group chose which feedback topics they would receive information about throughout the course; control instructors were randomly assigned feedback topics to match the distribution and sequence chosen by the treatment group. Thus, in expectation, treatment and control instructors that differ only on whether they chose the feedback topics they received, as both groups received feedback on the same topics. Because the intervention offered a one-time selection from a finite set of feedback topics, it mirrors common real-world contexts in which teachers choose among professional development offerings or identify a limited set of focus skills within an evaluation cycle. By offering the first causal evidence on the impact of choice of topics for instructor training, our study informs theory and practice related to the design of effective educator training systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Educator Agency and Choice

Although our experiment takes place in the context of instructor training for an online course, we turn to the K-12 literature on teacher professional learning to provide grounding in educator agency and choice since scholars have elucidated these concepts most completely within this domain. We discuss below how differences between K-12 settings and Code In Place instructor training program might impact the generalizability of our findings.

Scholars in the K-12 literature suggest educator agency plays an important role in teachers’ workplace experiences and, potentially, instructional quality. Most broadly, educator agency can be defined as “[educator’s] capacity to make choices, take principled action, and enact change” (Anderson, 2010, p. 541). In K-12 settings, it often refers to control over various job-related tasks, including addressing student needs, choosing curriculum materials, and designing solutions to problems of practice (Priestley et al., 2015).

Arguments for educator agency in shaping or choosing professional learning often rest on theories of adult learning (Knowles, 1984; Merriam, 2001), which hold that, in contrast to children, adults see themselves as agentic and thus best able to direct their own development as a professional. In this view, motivation to learn is key—adult learning is typically voluntary and will not occur without the full engagement of the learner. Together with the observation that most adults have reservoirs of experience to draw on while learning, this view motivates several broad forms of educator learning, including reflection (Schön, 2017), action research (Morales, 2016), study groups (Stanley, 2011, inter alia), and professional learning communities (Stoll et al., 2006). More recently, scholars have studied agency within educator professional learning settings in its own right: As Vähäsantanen et al. (2017) report, “professional agency and supportive social affordances for its enactment are essential to the processes of work-related learning and organisational development” (p. 514).

A key arena for educator agency involves choices about formal professional learning experiences. Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) first introduced agency into debates about teacher professional learning, noting that, in contrast to literature that frames teacher learning as training, “The key shift is one of agency: from programs that change teachers to teachers as active learners shaping their professional growth” (p. 948). Many in the K-12 scholarly community argue that teacher agency over their professional learning—whether operationalized as choice to engage in specific offerings or opportunities to shape the topics addressed in those experiences—is fundamental to teacher learning (Lieberman & Pointer Mace, 2008; Smith, 2017, inter alia), a view echoed in studies of post-secondary educator training (Chadha, 2013). Mechanisms through which choice may work include educators seeking learning opportunities related to areas of need, and enhancing engagement by treating educators as autonomous professionals capable of making their own decisions about learning (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2014; Calvert, 2016).

Molla and Nolan (2020) suggest two types of agency and choice particularly relevant to professional growth. In the first, inquisitive agency, educators choose their own professional learning experiences. This corresponds to choice about which and how much professional learning to attend; it extends, as in this study, to choosing areas for feedback and growth. In the second, deliberative agency, educators choose to engage in active reflection and refinement of their practices. This corresponds to taking up opportunities to learn as presented, in this case using professional learning material and feedback to drive one’s own improvement. In both, agency is expressed as the choices educators make over what and whether to learn, a definition we take forward into our study.

2.2. Empirical Studies of Educator Choice in Professional Learning

Again, we borrow from the literature on K-12 schooling to understand empirical approaches to studying choice, and the results of such studies. Despite strong theoretical warrants for studying the role of educator choice over their professional learning, relatively few empirical studies on this topic exist. Among those that do exist, one theme is educator dissatisfaction with situations in which choice over professional learning is constrained. For instance, interviews with Australian teachers conducted by Mohammad Nezhad and Stolz (2024) indicate that many felt a lack of voice in typical, school-directed professional learning experiences. Chadha (2013) similarly described a graduate student instructor training program that required attendance by its participants, contributing to widespread dissatisfaction with the program. When choice is not allowed, these authors argue, teachers may limit their active engagement in the professional learning, experience the stifling of professional culture, and curtail their changes in practice.

Researchers synthesizing evaluations of K-12 professional development have provided conflicting evidence about teacher choice over their professional learning. A review of 28 studies by Kennedy (2016a) suggests that mandatory teacher professional learning does not lead to changes in instruction or student outcomes, while a meta-analysis of 95 studies by Lynch et al. (2019) finds no difference in effectiveness between mandated vs. voluntary professional learning. Studies also note that teachers who are engaged in such studies of professional learning frequently choose actively to do so (Philpott & Oates, 2017; Fischer et al., 2019) and that their professional learning preferences may lead to different outcomes (Hübner et al., 2021), but these investigations rarely compare learning situations chosen by teachers to learning situations not chosen by teachers.

2.3. Automated Feedback on Instruction

Scholars have long recognized that regular, formative feedback is vital for professional growth (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Hill, 2009). Yet, questions remain about how to optimize such feedback systems. Theory suggests that giving educators choice about which aspects of their practice to focus on when receiving feedback could improve engagement and learning (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Molla & Nolan, 2020). However, empirical evidence on the impact of choice in feedback systems is limited, likely due to the small scale of most of these studies (Kraft et al., 2018) and to the challenges relating to systematically varying agency within a single feedback model. Further, testing the impact of design features like agency or choice over feedback requires keeping the content of that feedback constant across both educators who have and who do not have choice, something that is difficult to do in real-world settings.

Computational approaches, particularly those leveraging natural language processing, create new possibilities for studying how choice over the topic of feedback might affect the uptake and effectiveness of feedback. Because they automatically analyze multiple aspects of instruction simultaneously—such as questioning patterns (Kelly et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2020), dialogic teaching strategies (Suresh et al., 2021), and responsiveness to student contributions (Demszky et al., 2021)—feedback tools can offer educators choice over their focus areas while maintaining consistency in measurement. The computational methods and feedback tools like the ones described below also allow for experimental studies in two ways. First, they allow researchers to precisely match the feedback content delivered to individuals who do and do not have choice over feedback topic, thus providing a fair test of the choice itself. Second, computational methods and automated feedback tools allow for larger-scale experiments. Because all participants receive the same content and only vary by whether they have choice over that content, expected effects are small, meaning larger samples are needed for adequate power.

Early implementations of automated feedback systems show the promise of these tools. Automated feedback has been found to improve educator practice in targeted areas, such as increasing student talk time (Wang et al., 2013), uptake of student contributions (Demszky et al., 2023; Demszky & Liu, 2023), use of focusing questions (Demszky et al., 2024) and other dialogic practices (Jacobs et al., 2022). Many of these studies were conducted in online contexts, where digital platforms facilitate the recording and analyzes of classroom interactions. Furthermore, the feedback tools used in these studies, including LENA, M-Powering Teachers, the Talk Moves application, and TeachFX, foster agency by design, as the feedback is descriptive rather than evaluative, and because educators engage with it on their own time as a way to self-reflect. At the same time, in prior studies have indicated room for improvement in educator engagement with automated feedback. Since choice is theorized to increase engagement, this study has practical implications for the design of automated feedback systems.

2.4. Instructors Versus K-12 Educators

We have reviewed scholarship on K-12 educators that describes both theory and empirical evidence regarding the impact of choice on professional learning in those settings. The instructors in our study are different: most are not career educators and in fact, most are new to teaching in this online course; they are temporarily volunteering for a large online course rather than employed by a district or school; their motivation to improve their instruction was unknown; and unlike K-12, where educators might be given agency to choose from a wide variety of topics related to serving students’ needs, the choices offered to our instructors focused on dialogic instructional moves, described below, that they could implement in a prepared curriculum. Additionally, training on these dialogic moves was voluntary, meaning instructors did not have to open the email containing feedback or participate in the training modules. However, there are significant similarities between our instructor population and K-12 teachers along several more theoretical and practical dimensions. Both our instructors and the K-12 teachers featured in the professional learning literature are learning about instruction. Further, Molla and Nolan’s (2020) concepts of inquisitive and deliberative agency both apply to the automated feedback delivered in our treatment group, the first in the sense of choice of their own training experiences, and the second in the sense of choosing to take information from the automated feedback and using it for reflection and improvement. Finally, we argue that the underlying mechanisms that could make choice effective—increasing agency in order to enhance engagement and producing a better match to needed areas of improvement—apply to both K-12 teachers and to our instructors, thus motivating our experiment.

3. Study Background

We conducted the study during the spring of 2023 as part of Code in Place, a free, online, 6-week-long introductory programming course. Anyone could apply to serve as a volunteer section leader (henceforth, instructor) for the course by submitting a programming exercise and a 5 min video of themselves teaching; course organizers selected instructors based on this application. Students applied by completing several lessons and assignments. Each instructor was assigned to 12.1 ± 2.1 students.1 Once per week (between Wednesday and Friday), instructors held a 1 h session for students in their group to cover material and answer questions related to lectures and assignments from the course. The materials were prepared by course organizers and were uniform across instructors. Sessions took place on Zoom and were recorded and automatically transcribed by Zoom’s built-in transcription service. Instructors received automated feedback based on their transcripts; half of the instructors, as described below, had the option to choose among different types of feedback. The study was approved under institutional IRB.

3.1. Participants

Our participant sample consisted of all adult (18+) instructors in Code in Place (N = 583). Table 1 shows the demographics of our analytic sample, based on information that Code in Place collected during the instructor application process. In terms of gender, 66% of instructors identified as male, 32% as female, 1% as nonbinary, and 1% as other or “prefer not to say.” The instructors ranged in age from 18 to 75 years, with an average of roughly 30 years old. They were located in 70 unique countries, with about 48% in the United States; three-quarters (75%) were first-time instructors for Code in Place in 2023. Based on their open-ended responses about their background, the majority were young professionals working in the technology industry and had limited prior teaching experience. Their motivation to teach came from wanting to help beginners overcome their fears, be part of a supportive global community, and “pay forward” the education they once received. Many also saw teaching as a way to improve their communication, leadership, and coding skills.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the analytic sample.

Our analytic sample also included 8,254 students who were taught by these instructors. Students were more balanced in terms of gender than instructors, with 52% identifying as female, 45% as male, 1% as nonbinary, and 2% as other or “prefer not to say.” Students were on average 31 years old, and they were located in 145 unique countries, with about 28% in the United States.

3.2. Automated Feedback to Instructors

All instructors received automated feedback on their instruction during the weekend following each session. The feedback was generated via a three-step process: First, we used Zoom to record and automatically transcribe the session; next, we analyzed the transcripts using a set of natural language processing models; then, we used the results of these analyses to generate feedback for instructors. We describe the latter two steps below.

Transcript analysis. We developed and applied measures to identify three instructor moves in session transcripts: Getting Ideas On the Table (e.g., “Who would like to share their solution?”), Building On Ideas (e.g., “Can you explain why you used a ‘for’ loop?”), Orienting Students to One Another (e.g., “Bryan and Jen used a similar approach—do you see how?”). These moves were inspired by the Accountable Talk framework (O’Connor et al., 2015), which proposes these moves to be ones that facilitate students’ active participation in learning. Our choice for these moves, henceforth referred to as feedback topics, was also motivated by the fact that the instructor training team for Code in Place decided to create training modules for these moves. By creating measures that correspond to these modules, we hoped to create a consistent and more holistic learning experience for instructors that built on their initial training. Prior work has employed the Accountable Talk framework to develop automated measures based on K-12 transcripts (Suresh et al., 2021; Jacobs et al., 2022). Kupor et al. (2023) leveraged transcripts from a prior Code in Place course (from 2021) to develop such measures for the Code in Place domain. They annotated 2000 instructor moves for five talk moves (eliciting, revoicing, adding on, probing, and connecting students’ ideas) and fine-tuned RoBERTa (Liu, 2019) models to create classifiers for these moves. The feedback topics in this study correspond to models created by Kupor et al. (2023) in the following way: Getting Ideas On the Table corresponds to “eliciting,” Building On Ideas corresponds to “revoicing,” “probing” and “adding on,” and Orienting Students to One Another corresponds to “connecting.”

We additionally used GPT-3 (specifically text-davinci-0032) to generate experimental insights into a summary of what happened during the class as well as specific moments when the instructor or student exhibited curiosity. This feedback was separate from the feedback on talk moves, and we only provided these insights to a subset of instructors during their last 2 weeks in the course. The supplement includes the prompt we used to generate these insights.

Displaying feedback to instructors. Similarly to prior work on automated feedback to educators (Demszky et al., 2023; Jacobs et al., 2022), our goal was to generate nonjudgmental, concise, and actionable feedback to instructors that would encourage self-reflection as a mechanism for instructional improvement. Feedback was private to each instructor, and it always focused on a single topic at a time. Instructors received feedback on the same topic for two consecutive weeks. The topic assignment criteria by experimental condition are described in detail below.

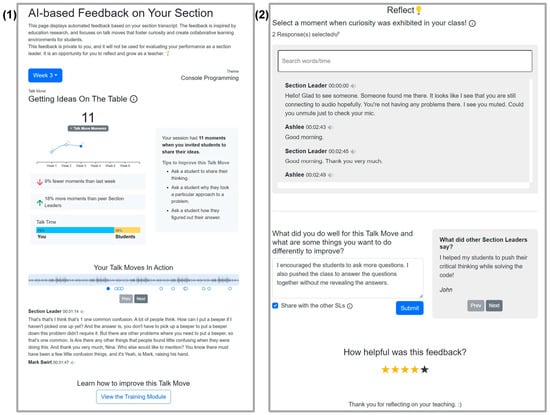

The feedback included the following components (see Figure 1): an introduction to the feedback; the week and theme for the session; summary statistics for a given talk move; relative change in the frequency of that talk move compared to prior weeks; the talk ratio between the instructor and students; specific instances of the given talk move in the instructor’s transcript; and a link to a relevant training module. The page additionally included the instructor’s full transcript and a box they could use to search and identify moments for reflection, as well as a reflection question: “What did you do well for this Talk Move, and what are some things you want to do differently to improve?” Instructors could opt in to share their responses to the reflection question with other instructors and could view their reflections. Finally, instructors could rate the feedback on a scale of 1 to 5 stars.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the feedback page, with a focus on the “Getting Ideas On the Table” talk move. Subfigures (1) and (2) are components of a single scrollable page.

4. Randomized Controlled Trial

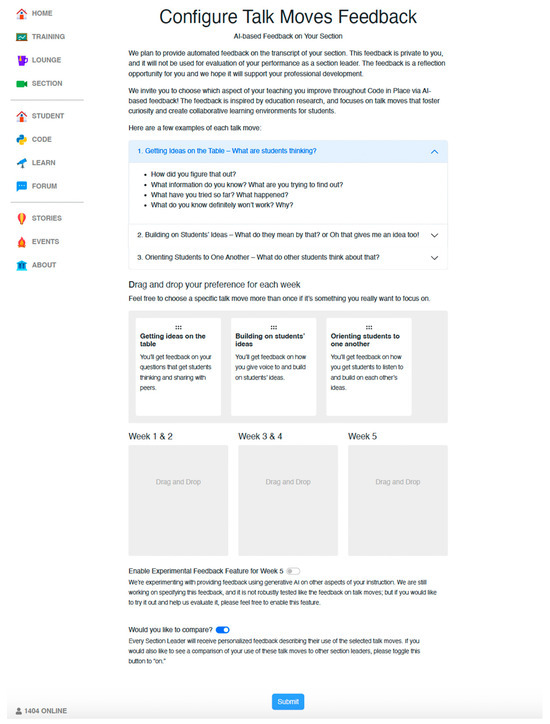

We randomized instructors once they were accepted to teach in the course, before the course began. Half of them received a choice of feedback topic. Instructors were asked to make this choice on the Code in Place website (Figure 2), as an action item on their precourse checklist. The choice involved feedback on three talk move topics (Getting Ideas On the Table, Building On Ideas, Orienting Students to One Another), which they could select for pairs of weeks (Weeks 1–2, 3–4, or 5–63). Instructors also toggled between two options: They could enable experimental GPT-based feedback for the last 2 weeks, and they could enable seeing how their metrics compared with those of other instructors for all weeks. Below each talk move, we displayed a short definition and an example to help inform their choices. Before the course began, we sent instructors up to three email nudges to make a choice. About 80% of treatment group instructors made a choice of feedback topic.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the configure talk moves feedback page.

The control group did not have the option to choose feedback topics. Instead, these instructors were randomly assigned feedback under the constraint that the distribution and sequence of feedback patterns in the control group were the same as the distribution in the treatment group. For example, 36% of the treatment group chose the following pattern: two weeks on Getting Ideas On the Table, two weeks on Building On Ideas, two weeks of experimental feedback, and comparison of metrics to instructors. Thus, 36% of the control group was assigned to that same pattern. As such, the only difference between treatment and control, in expectation, is whether the instructor chose their pattern of feedback or was assigned their pattern of feedback. The 20% of treatment group instructors who did not choose feedback were assigned feedback with the same weighted random assignment method as the control group, and remained part of the treatment group. This design allows us to estimate the policy-relevant effect of offering choice (intent-to-treat), rather than taking up choice.

This experimental design reflects choice along at least three dimensions. First, educators could choose their feedback types—selecting among three topics, as well as experimental feedback, and whether they wanted to compare their metrics with other educators. Second, educators could choose the sequencing (i.e., timing) of their feedback. Third, educators could decide if they wanted to engage with the feedback—we treat this decision as an outcome, as described below. Consistent with the mechanisms identified above, we theorized two mechanisms by which choice could affect feedback uptake: improved alignment between the feedback focus and an instructor’s needs (less likely here, given the limited option set) and heightened engagement with the feedback (more likely in this context).

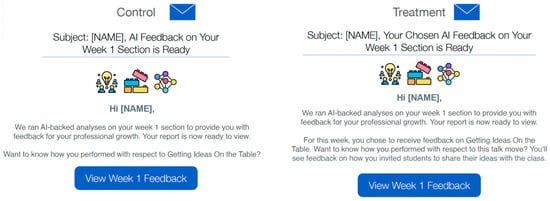

4.1. Emails About Feedback

At the end of each week, when all feedback was ready, we released it to all instructors at once, both by displaying it to them on the course platform and by emailing them that their feedback was ready. The email was short and did not contain any of the feedback itself—it merely included a link to the feedback page. However, the content did differ slightly based on condition. As illustrated in Figure 3, in order to reinforce the effect of the treatment, treatment group instructors were reminded in the email (both in the subject line and content) that they had chosen the focus of the feedback.

Figure 3.

Example email received by control and treatment group instructors when the feedback was ready.

4.2. Measures of Outcomes

We measured four key types of outcomes to evaluate the impact of giving instructors choice over their feedback, mixing teacher self-report with behavioral and student outcomes. These measures thus capture both immediate instructor responses (engagement, perception) and downstream effects on teaching practice and student outcomes.

Engagement With Automated Feedback. Instructor-level measures of engagement with automated feedback are based on their engagement with the feedback page.

- Ever Viewed: Whether instructors ever viewed their feedback before their subsequent session (binary). We also tracked the number of times they viewed the feedback, but the results were similar to Ever Viewed—hence, we use this binary measure.

- Seconds Spent: Total seconds spent viewing feedback across weeks.

Perception of Feedback. Instructor-level measures of perception of feedback are based on a post-course survey. Survey questions are included in Appendix B. While the relatively low response rate of 33% limits the conclusions we can draw from these analyses, we focus on the following items:

- Net Promoter Score (NPS): 1–10 rating of the likelihood of recommending the feedback tool.

- Overall Perception: Aggregated items from the final instructor survey measuring perceptions of feedback utility and satisfaction. As explained in the preregistration, a factor analysis showed a single dominant factor explaining most variance; hence, we mean-aggregated the items.

Changes in Instructional Practice. We measured changes along the three talk moves that the automated feedback was targeting. We calculated the hourly rate of each talk move by dividing the frequency of the talk move for a given session by the session duration in minutes, and then multiplying that number by 60. Finally, we standardized the talk move rates within each talk move (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1) to account for differences in talk move frequencies (e.g., Getting Ideas On the Table is about 8 times as frequent on average as Orienting Students to One Another). This standardization enabled us to combine all talk moves into a single model as outcomes, as explained in the next section.

Since the treatment (i.e., making a feedback choice) was delivered before the course began, it could have impacted baseline, prefeedback instructional practices. Thus, we created two separate outcome variables at the instructor-week-talk move level:

- Week 1 Talk Move Rate: The standardized talk move rate(s) within the first session, across all talk moves. This measure captures discourse practices after treatment, but before instructors received any feedback.

- Week 2+ Talk Move Rate: The standardized talk move rate(s) within the second through sixth sessions, across all talk moves. This measure captures discourse practices after instructors received their first feedback. To improve precision, in models that use this outcome we controlled for talk move rates in the first session.

Student Outcomes. The course did not have any mandatory assignments. Attending sessions and completing assignments were the key indicators of student success in the course, and we used these student-level measures as outcome features.

- Number of Sessions Attended: Number of sessions attended by students between Week 2 and Week 6. We excluded attendance at the first session—while the first session was after random assignment, students did not interact with instructors until showing up (or not) for this session; thus, attendance at the first session could not have been affected by treatment.

- Number of Assignments Completed: The total number of assignments completed by summing completion rates across the six course assignments (usually one assignment per week).

4.3. Variables for Subgroup Analysis

We completed a subgroup analysis to determine whether instructor characteristics interacted with choice of topic to affect study outcomes. As noted in our preregistration, we considered demographic characteristics of the instructor (gender, age, location, and whether they were returning as instructors in Code in Place) as well as behavioral characteristics. For behavioral characteristics, we considered whether the instructor engaged with two other forms of self-directed training on the platform, both available after randomization but prior to the first session:

- Training Modules About Talk Moves: The four optional training modules included interactive videos and reflection questions related to each of the three talk moves (Getting Ideas On the Table, Building On Ideas, Orienting Students to One Another), as well as a module synthesizing all three. We used a binary measure indicating whether the instructor completed any of these modules. (Using the number of completed modules did not change our results.) Overall, 43% of instructors completed at least one training module.

- GPTeach: GPTeach (Markel et al., 2023) is an LLM-powered chat-based training tool that allows instructors to practice engaging with simulated students. Created via GPT-3, the simulated students had diverse backgrounds and familiarity with course material (programming), and the instructor was asked to facilitate office hours with these simulated students. We used a binary measure indicating whether the instructor accessed GPTeach; however, using the number of times they accessed GPTeach did not change our results. Overall, 23% of instructors accessed GPTeach at least once during the course.

Since these training resources were available to instructors postrandomization, the treatment (choice) may have influenced whether they engaged with the tools. However, using a t-test, we found no statistically significant difference by condition for completing any training module (t = 0.022, p = 0.983) or accessing GPTeach (t = 0.092, p = 0.927). This suggests no observable correlation between these moderator variables (engagement with training resources) and our key independent variable (condition). However, these moderators could still have influenced the relationship between the condition and the dependent variables (outcomes) listed above.

4.4. Validating Randomization

To verify whether our randomization created groups that were balanced on observable variables, we evaluated whether the demographics of instructors in the treatment and control groups differed statistically. As Table 2 shows, we found no statistically significant differences in instructor demographics by condition. To examine whether the treatment and control conditions suffered from differential attrition, we also conducted an attrition analysis by calculating the number of transcripts available for each instructor. Attrition in our data occurred when instructors missed a session or a session was canceled, leading to a missed transcript. We found no statistically significant differences in the number of recordings per instructor by condition. Finally, when comparing the section demographics (gender, age, and location of students), we found that instructors in the control group had a significantly higher proportion of students in the United States. However, since we controlled for this variable, this difference should not affect our results.

Table 2.

Randomization check.

4.5. Regression Analysis

We conducted a preregistered intent-to-treat analysis (Anonymized for peer review) using ordinary least squares regression. The analysis compared instructors by condition rather than by compliance (i.e., whether they made a choice over feedback), since the latter could introduce selection bias: Instructors who made a choice to access the feedback may have had different characteristics (e.g., more time or motivation for self-directed learning) than those who did not. The intent-to-treat analysis preserves experimental comparability and yields a policy-relevant estimand—the effect of offering choice—which averages over both choosers and non-choosers and therefore generalizes to settings where some participants decline to choose.

RQ1: Impact on Instruction Engagement with and Perception of Feedback. For instructor-level outcomes, we fit the following specification:

where Yi refers to the outcome measure for instructor i; Ti is a binary treatment indicator (1 if instructor i was assigned to choose their feedback type); Xi is a vector of instructor and student covariates; and εi indicates the residuals. The instructor covariates include age, gender (binary female indicator), location (binary U.S. indicator), and whether they were a returning Code in Place instructor. Student covariates, averaged at the section level, include age, gender composition, and location.

Yi = δTi + Xiβ + εi

RQ2: Impact on Talk Moves. When using talk moves as outcomes, we pooled together all moves into one estimation sample. By pooling all talk moves together, we preserved balance in the experiment and avoided selection bias. Consider the alternative, where we would not pool but instead condition on feedback type (i.e., limiting the estimation sample to instructors who all received feedback on the same topic the same week). In that alternative, the treatment instructors would be a self-selected subset of the full treatment group, because they chose the feedback topic, but control instructors would be a randomly selected subset of the full control group. The treatment and control would no be longer balanced by random assignment, raising the potential for bias.

Before pooling, we standardized each talk move outcome (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1, using the full sample), so the outcome would be in standard deviation units. By pooling together, we expected to gain more power at the expense of some interpretability. Since each instructor had three talk move outcomes for each week, the specification becomes the following:

where Yiwm refers to the standardized rate for instructor i in week w and for move m; Ti is a binary treatment indicator; Xi is a vector of instructor and student covariates, same as above; πw represents week fixed effects; θm represents talk move fixed effects; and εiwm indicates the residuals. For models examining changes in instructional practice in Weeks 2–6, we additionally included the Week 1 (baseline) rate of each of the three talk moves as controls in Xi. The point estimates are similar if we omit the Week 1 controls (see Appendix C). We clustered standard errors at the instructor level.

Yiwm = δTi + Xi β + πw + θm + εiwm

RQ3: Impact on Student Outcomes. For student outcomes, the specification is as follows:

where students are indexed by j, and i(j) indicates the instructor of student j. In Xi(j) we include the same instructor covariates as above as well as the demographics (age, gender, location) of the student j. We clustered standard errors at the instructor level.

Yj = δTi(j) + Xi(j)β + εj

Subgroup Analysis. To examine how feedback choice interacts with instructor characteristics or behavior, we augmented the above models with an interaction term γ(Ti ∗ Fi), where Fi represents a given instructor feature listed in the Variables for Subgroup Analysis section. The coefficient γ captures whether the treatment effect was larger when instructors had a certain characteristic or not.

5. Results

This section provides a summary of findings in response to each of our preregistered research questions.

RQ1.

Does providing instructors choice over feedback impact their engagement with the feedback, their perception of the feedback, or their teaching practice?

We found that the treatment did not, on average, significantly impact instructors’ engagement with the feedback, their perception of the feedback, or their teaching practice. As shown in Table 3, across all outcome measures, the effects were statistically insignificant and relatively small in magnitude.

Table 3.

Treatment effects on instructor outcomes.

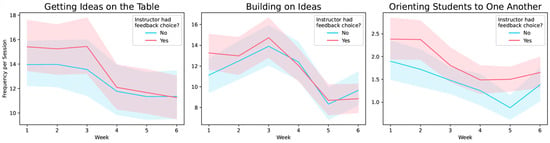

However, examining patterns over time reveals interesting trends. As shown in Figure 4, treatment group instructors tended to use more talk moves than control group instructors, particularly in the first 3 weeks of the course. This pattern was most pronounced for the Orienting Students to One Another move, where treatment instructors maintained consistently higher rates throughout the course. While these differences did not reach statistical significance, they suggest that having choice over feedback may have had a positive impact on some aspects of instructional practice.

RQ2.

Does choice over feedback for instructors impact their students’ outcomes?

Figure 4.

Talk move rates over time by condition. The two lines indicate control (blue) and treatment (red) conditions. Shaded bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

Next, we examined whether the treatment impacted student outcomes, including attendance and assignment completions. Unexpectedly, we found a small but statistically significant positive effect on student attendance. As shown in Table 4, students whose instructors had choice over feedback attended on average 0.112 more sessions compared to the control group (SE = 0.048, p < 0.05). This represents a meaningful increase of about 3.1% over the control mean of 3.575 sessions.

Table 4.

Treatment effects on student outcomes.

Given that students were unaware of the intervention, this effect was likely mediated through changes in instructor behavior. While we did not detect significant changes in our measured instructional practices (Table 3), the differences may still have been substantial enough in terms of instructional quality—particularly in the early weeks of the course—to impact student attendance. The treatment also may have influenced other aspects of instruction that impacted student engagement. For assignment completions, we found no significant treatment effects—the coefficients were consistently positive but small for each assignment (ranging from 0.001 to 0.015, all p > 0.05).

RQ3.

How do treatment effects vary by instructor demographics and whether the instructor engages with self-directed training beyond automated feedback?

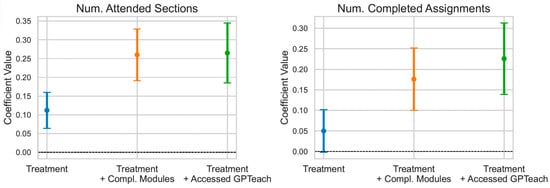

Finally, we turn to examining subgroup treatment effects. We did not find any notable variation in treatment effects based on instructor gender, U.S. location, or their returning instructor status (Appendix D). We did find, however, interesting subgroup differences based on engagement with self-directed training resources. Figure 5 illustrates that students of instructors who engaged with training resources, including training modules and GPTeach, had the best outcomes. As a reminder, these tools were available to instructors postrandomization, but instructors’ likelihood of engaging with them did not significantly differ by condition.

Figure 5.

Treatment effects on the number of attended sessions and number of completed assignments. The lines represent the entire treatment group (values are same as in Table 4), the subset of the treatment group that also completed a training module (values are same as in Table 5 Columns 7–8, Row (c)) and another subset of the treatment group that accessed GPTeach (values are same as in Table 6 Columns 7–8, Row (c)), respectively. The bands represent standard errors.

As shown in the subgroup comparison in Table 5 and Table 6, instructors who completed training modules used more talk moves (+0.198, p < 0.05 in Week 1; +0.135, p < 0.10 in Weeks 2+), and their students attended 0.260 more sessions (p < 0.01) and completed 0.176 more assignments (p < 0.05) than students of control group instructors who did not complete the modules. Similarly, as shown in Table 6, students whose instructors were in the treatment group and accessed GPTeach attended 0.265 more sessions (p < 0.01) and completed 0.226 more assignments (p < 0.01) than students of control group instructors who did not access GPTeach. These effects are about 2–4 times greater than those reported in Table 4 for all treatment group instructors.

Table 5.

Treatment effects based on whether instructors completed any of the four optional training modules (moderator).

Table 6.

Treatment effects based on whether instructors engaged with GPTeach (moderator).

One might ask: Could the increased coefficients in Figure 5 be associated with characteristics of instructors who use training resources, rather than the impact of choice? Our results suggest otherwise. We find that providing instructors with choice had benefits to students above and beyond the resources: Students of treated instructors who completed modules attended more sessions (+0.147, p < 0.05) and completed slightly more assignments (+0.118, p = 0.131) than students of control group instructors who completed modules. Analogically, students of treated instructors who accessed GPTeach attended more sessions (+0.216, p < 0.05) than students of control group instructors who accessed GPTeach. Altogether, these results indicate that both providing choice over feedback to instructors and instructors’ engagement with training resources had greater benefits for students than choice or engagement with the resources alone.

However, we did not observe the same added benefit of the treatment for instructors who used training resources for other outcomes. Interestingly, it seems that treated instructors who engaged with these resources spent less time on the feedback than control group instructors who engaged with the resources. This trend is negative for all four outcomes (Columns 1 and 2 in Table 5 and Table 6), but it is only significant for one of the values: Among instructors who accessed GPTeach, those in the treatment group were about 8% less likely to view the feedback than those in the control group (p < 0.05).

This decrease in engagement may have been driven by treated instructors who were offered a choice but decided not to make one: This subgroup of the treatment group (n = 44) was 26% less likely than the control group to check the feedback (p < 0.001). When we removed this subgroup, there was no longer a significant difference by condition in engagement with feedback—either overall, or for the subgroup who used GPTeach. This suggests that offering feedback choice to instructors who do not desire to make choices may harm their engagement with feedback.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary and Theoretical Implications

Our study is among the first to offer experimental evidence on the role of educator agency in choosing their training experiences. Prior work has relied on theory and qualitative methods, such as self-reports, interviews, or case studies, to suggest that granting educators more autonomy over their learning fosters professional growth (Molla & Nolan, 2020; Priestley et al., 2015; Brodie, 2021; Martin et al., 2019; Philpott & Oates, 2017; Brod et al., 2023). These studies have illustrated that when educators perceive themselves as active agents in their learning, they are more likely to integrate new strategies into their practice. However, such studies could not disentangle the impact of agency on instruction from other factors, such as educators’ intrinsic motivation or features of the programs under study. To fill this gap, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to test whether providing volunteer instructors with choice over their feedback topics improved engagement with feedback, instructional practice, and student outcomes. Random assignment helped isolate the effect of choice from other factors, allowing us to test whether this aspect of educator agency contributes to improved instruction as well as outcomes for learners.

Our results paint a nuanced picture. While we observed a positive trend in treated instructors’ use of high-leverage talk moves, choice over feedback alone did not lead to significant changes in observed instructor behavior. This finding aligns with prior work suggesting that while choice can be empowering—e.g., by fostering inquisitive agency (Molla & Nolan, 2020), it does not guarantee meaningful engagement or skill acquisition (Lynch et al., 2019). At the same time, we found a significant and unexpected effect of choice on student attendance. Students taught by instructors who received choice over their feedback attended more sessions on average than those in the control group. At least two possibilities exist given these findings. First, it could be that the non-significant differences in instruction we observed were nevertheless substantial enough to yield differences in students’ class attendance. Second, it could be that instructors changed aspects of their instruction that were not detected using our computational models.

Because this study took place with voluntary instructors in an online program, we do not claim that these experimental results generalize to school- or university-based professional learning. However, we can observe that our results are consistent with some but not all mechanisms hypothesized in the literature on educator agency. Our instructors did not engage more with feedback on average as a result of the experimental choice, meaning that our results do not support the notion that choice would lead to heightened feelings of autonomy and thus engagement. The kind of choice we offered, combined with the sample of volunteer instructors we enrolled, may not have been enough to trigger such engagement in this setting. Yet by choosing the type and order of the automated feedback, instructors may have better matched the feedback to anticipated (or perceived) gaps in their teaching, leading to the impacts on students we observed. Our results are also consistent with Clarke and Hollingsworth’s (2002) Interconnected Model, which holds that a light-touch external input (bounded choice) can shift instructors’ goals or attention and thereby improve student “consequences” before detectable changes occur in specific instructional practices.

For the subgroup of treatment instructors who engaged with additional training resources, including training modules and teaching simulations, we observed greater treatment effects on student attendance. This effect again does not appear to operate through increased engagement with the feedback, suggesting that information contained in the training modules or teaching simulation might have helped activate the feedback these instructors viewed, making it more salient and actionable. Interpreted through Molla and Nolan’s (2020) framework, a combination of inquisitive agency (choice of feedback focus) and deliberative agency (more in-depth uptake of training and refinement) appears to drive greater instructional improvement than these forms of agency in isolation.

At the same time, we also have evidence to suggest that offering choice to instructors who are not interested in making choices may be detrimental to their engagement with feedback. Thus, agency over training appears to be most beneficial when instructors are intrinsically motivated to engage in further learning. These findings align with theories of adult learning that suggest that agency is most impactful when learners have both the autonomy to make choices and the internal motivation to act upon them (Deci & Ryan, 2013; O’Brien & Reale, 2021).

6.2. Practical Implications

The lack of a widespread benefit of choice over feedback topics to instructors raises practical questions about the optimal integration of this type of choice into similar types of educator training programs. Our findings suggest that offering choice in a setting similar to this one—a voluntary, online training program—may only marginally increase student engagement with assignments. If choice is low-cost to implement, in terms of instructor time, integrating choice into online learning opportunities may be desirable. However, our findings also suggest that offering choice to individuals who are also otherwise engaged in teaching-related opportunities to learn would make the choice more effective. If such individuals can be identified (for instance, those who finish at least one online module), the impacts of choice could be substantially greater.

Another set of practical implications relates to our experimental approach for testing educator choice over feedback content. Similar methods could evaluate other design features, such as balancing general instructional principles with specific, actionable guidance, or determining the value of integrating teacher reflection into training opportunities. Since varying these design features typically results in subtle differences in the delivery of programs, ensuring sufficient statistical power to detect potentially small effects is crucial. While partnering with online providers has certain limitations, as discussed below, it also offers opportunities to achieve the statistical power needed to identify small yet meaningful effects.

6.3. Limitations

Although our study yields valuable insights, questions remain about the generalizability of the findings. First, our study was conducted in a unique context—an online programming course with volunteer instructors who had diverse backgrounds, teaching experiences, motivations, and constraints on their time, as discussed earlier. Some may have been particularly motivated to improve their teaching and engage with optional resources, while others may not have had the interest or time to do so. The effects of choice over the focus of feedback might differ in traditional K-12 or higher education settings with trained educators who have institutional structures and incentives to participate in professional learning (Mohammad Nezhad & Stolz, 2024).

Second, we could offer only constrained choice within our experiment—i.e., a one-time choice regarding receiving information about three different talk moves and feedback about instructor and student curiosity. A wider array of choices, as might occur in K-12 or higher education settings where educators choose from a menu of diverse options, may heighten the educator’s sense of agency and control over their learning. Allowing more choices consistently across a longer time span may also make this aspect of the training experience more salient and potentially more motivating for educators.

Third, the automated measures of teaching behaviors we employed, while convenient and scalable, are imperfect (Kupor et al., 2023) and cannot capture the full complexity of instructional change. Prior work on teacher agency highlights how changes in practice can be subtle, multifaceted, and best captured through multimethod triangulation (Biesta et al., 2015). The fact that we observed positive student attendance effects despite modest changes in measured instructional practices suggests there may be important, unmeasured dimensions of teacher–student interactions at play.

Fourth, although we hypothesized that instructors’ decisions to explore optional training resources were driven by their motivation, it is also possible that they were driven by other factors, such as available time or self-efficacy. To better isolate the role of different factors, future research might incorporate direct measures of teacher motivation, self-regulatory capacity, and sense of agency based on existing frameworks (Brod et al., 2023).

6.4. Future Directions

There are several avenues to build on this work. In order to keep our intervention “light-touch” and minimize the time volunteer instructors would need to make a choice, we provided minimal scaffolding for choices. However, additional scaffolding could increase instructors’ motivation and deliberative engagement with choices. For example, programs where instructors have more time to engage in training could include core pathways of “must-do” content for essential skills, then offer elective modules for instructors who wish to delve deeper into specific areas. Such programs could also embed self-assessment opportunities that prompt teachers to set goals or select topics based on their perceived strengths and weaknesses. These options would help maintain a coherent structure within a training program and accountability to key learning goals, while fostering a “pedagogy of choice” (O’Brien & Reale, 2021). In programs like Code in Place, where most instructors have minimal capacity to engage in training, gamification (e.g., with rewards) could motivate them to be intentional about improving their teaching. A hybrid training program could support educators with varying capacity as well as differentiate the degree of autonomy based on instructors’ readiness or willingness to engage in self-directed learning (Brod et al., 2023).

Second, replications in school- and university-embedded professional learning are needed to test whether the effects of choice operate similarly in these settings. Randomized studies that manipulate the degree of choice could illuminate the optimal balance between structure and autonomy in different contexts (Brod et al., 2023; O’Brien & Reale, 2021).

Third, drawing on learning analytics, one might design a training system to test the effectiveness of adapting the degree of instructor choice in real time (Chen et al., 2019). Such a system could dynamically adjust learning pathways—balancing freedom with structured supports—by monitoring metrics such as time spent on feedback, use of talk moves, or self-assessment responses. This approach would also advance the broader goal of designing personalized training that efficiently responds to teacher needs while maintaining quality and rigor.

Fourth, longer-term studies can help us understand how the effects of choice over feedback content might drive improvements over time. While this study captured short-term impacts of a light-touch intervention, follow-up work could explore how continued choices over a longer period impacts teaching practice and student outcomes (O’Brien & Reale, 2021).

Finally, we need to better understand the mechanisms linking educator agency regarding their training to student outcomes. Investigating how and why educator autonomy influences attendance, assignment completion, or other measures of student behavior will further clarify when and for whom agency is most beneficial. Altogether, these insights would fuel evidence-based and adaptive approaches to designing the future of educator training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D., H.C.H., E.T. and C.P.; Methodology, D.D., H.C.H. and E.T.; Software, A.K. and D.V.D.; Validation, D.D.; Formal analysis, D.D. and E.T.; Investigation, D.D., H.C.H. and C.P.; Data curation, D.D., A.K. and D.V.D.; Writing—original draft, D.D. and H.C.H.; Writing—review & editing, D.D., H.C.H., E.T. and C.P.; Visualization, D.D. and D.V.D.; Supervision, D.D. and H.C.H.; Project administration, D.D.; Funding acquisition, D.D. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful for the Carina Foundation for funding the Code in Place project. The APC was funded by the Stanford University Graduate School of Education (D.D.’s discretionary funds).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University (protocol code 68376 on 19 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Preregistration: https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/12746.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Aggregate and de-identified data and analysis scripts can be shared upon request. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate John Papay’s advice on experimental design. We would like to thank the Code in Place team for supporting us with the implementation of the experiment. Thanks to Jenny Osuna, Jim Malamut and Miroslav Suzara for brainstorming sessions related to the talk moves and for sharing information about the training modules.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Experimental Feedback

For Weeks 5–6, instructors had the option to choose “experimental feedback,” which was powered by GPT-3.5. We first split up the transcript into smaller sections due to the character limit for the model. For each section, we asked GPT to “Please summarize what happened in the following segment of the classroom session.” Then, we took each summary and asked GPT to summarize them all together with “Please summarize the following summaries of classroom sessions.” Additionally, we asked GPT to find moments of curiosity with the following prompt: “Please identify specific moments with the timestamp in the following transcript where the section leader or the students exhibited curiosity. For each moment, please tell me your reasoning for what they did that exhibited curiosity.”

Appendix B. Final Survey on AI Feedback

The final survey, administered to all instructors, included the questions below. We used two items from this survey as outcomes. For “Overall Perception,” we aggregated responses to items within Question 4 by converting the answer choices to a 5-point Likert scale, reversing the scale for Question 4c and taking the mean of the numeric responses. For “NPS,” we used responses to Question 5.

- How often did you engage with the AI teaching feedback?

- (a)

- Not at all.

- (b)

- Once or twice.

- (c)

- Regularly.

- Could you tell us why you didn’t engage with the AI teaching feedback? Select all that apply.

- (a)

- I didn’t know about it.

- (b)

- It wasn’t available to me.

- (c)

- I didn’t have the time.

- (d)

- I didn’t think it would be helpful.

- (e)

- Other (please explain).

- Could you tell us why you engaged with the AI teaching feedback only once or twice? Select all that apply.

- (a)

- I only learned about it later in the course.

- (b)

- It wasn’t available to me after each session.

- (c)

- I didn’t have the time.

- (d)

- I didn’t find it helpful.

- (e)

- Other (please explain).

- To what extent do you agree with the following about the AI teaching feedback? (Strongly disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Strongly agree)

- (a)

- The feedback has helped me become a better teacher.

- (b)

- The feedback made me realize things about my teaching that I otherwise would not have.

- (c)

- The feedback was difficult to understand.

- (d)

- The feedback made me pay more attention to the teaching strategies I was using.

- (e)

- I tried new things in my teaching because of this feedback.

- (f)

- The feedback areas (e.g., getting ideas on the table, building on student ideas, orienting students to one another) represented important aspects of good teaching.

- (g)

- The feedback allowed me to improve my teaching around areas that were important to me.

- (h)

- The feedback felt appropriate to my teaching strengths and weaknesses.

- (i)

- The feedback aligned with my priorities for growth in my teaching.

- How likely are you to recommend AI teaching feedback to other educators? (Scale of 1–10)

- How helpful was each of the following types of feedback?

- (a)

- Getting Ideas on the Table.

- (b)

- Building on Student Ideas.

- (c)

- Orienting Students to One Another.

- (d)

- Experimental (ChatGPT) Feedback.

- Please rank the different elements of feedback in terms of helpfulness.

- (a)

- Number of talk move moments identified.

- (b)

- Chart to compare the number of moments to previous weeks.

- (c)

- Comparison of the number of moments to class average.

- (d)

- Talk time percentage.

- (e)

- Tips to improve the talk move.

- (f)

- Examples from your transcript demonstrating the talk move.

- (g)

- Selecting moments when curiosity was exhibited.

- (h)

- Answering the reflection question.

- (i)

- Seeing other section leaders’ answers to the reflection question.

- (j)

- Resources to improve the talk move. (k) Other (please explain).

- Do you have any suggestions for how we could improve this feedback tool?

- Any other thoughts/comments?

Appendix C. Talk Move Rates for Weeks 2+ with No Week 1 Controls

Table A1.

Table 3 Column 6 with No Week 1 Controls.

Table A1.

Table 3 Column 6 with No Week 1 Controls.

| Week 2+ Talk Move Rate | |

|---|---|

| Treatment | 0.017 (0.047) |

| Control Mean | −0.014 |

| R2 | 0.023 |

| Observations | 7992 |

Appendix D. Heterogeneity by Instructor Demographics

Table A2.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor is Female.

Table A2.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor is Female.

| Engagement | Perception | Practice | Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Ever Viewed | Seconds Spent | NPS | Overall Perception | Wk 1 Talk Move Rate | Wk 2+ Talk Move Rate | Num. Sessions Attended | Num. Assn. Completed | |

| (a) Treatment = 0 # Female Instr. = 1 | −0.001 (0.039) | 79.820 (95.513) | 0.392 (0.566) | 0.232 (0.189) | 0.040 (0.114) | 0.012 (0.074) | 0.092 (0.074) | 0.010 (0.081) |

| (b) Treatment = 1 # Female Instr. = 0 | 0.004 (0.031) | 52.090 (86.134) | 0.140 (0.489) | 0.172 (0.151) | 0.104 (0.086) | 0.043 (0.057) | 0.147 * (0.058) | 0.059 (0.063) |

| (c) Treatment = 1 # Female Instr. = 1 | −0.069 (0.046) | 28.036 (100.069) | 0.136 (0.586) | 0.115 (0.198) | 0.079 (0.105) | −0.029 (0.072) | 0.127+ (0.074) | 0.041 (0.082) |

| (c)-(a) | −0.068 | −51.784 | −0.256 | −0.117 | 0.039 | −0.041 | 0.035 | 0.031 |

| (c)-(b) | −0.073 | −24.054 | −0.004 | −0.057 | −0.025 | −0.072 | −0.020 | −0.018 |

| Control Mean | 0.882 | 462.026 | 5.903 | 3.432 | −0.014 | −0.014 | 3.560 | 3.435 |

| R2 | 0.068 | 0.089 | 0.132 | 0.120 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.043 | 0.013 |

| Observations | 567 | 567 | 193 | 193 | 1611 | 7992 | 8254 | 8254 |

Notes. Standard errors in parentheses. Estimates are compared to the control group where the moderator variable is zero. The model specifications are the same as in Table 3 and Table 4, with an additional interaction term added as specified in Methods. Above we report the estimated total effect for each of the three groups, relative to nonfemales in the control group. The difference between point estimates are calculated with a robust Wald test. * p < 0.05.

Table A3.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor was a Returning Instructor in Code in Place.

Table A3.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor was a Returning Instructor in Code in Place.

| Engagement | Perception | Practice | Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Ever Viewed | Seconds Spent | NPS | Overall Perception | Wk 1 Talk Move Rate | Wk 2+ Talk Move Rate | Num. Sessions Attended | Num. Assn. Completed | |

| (a) Treatment = 0 # Returning Instr. = 1 | −0.067 (0.050) | −319.437 ** (116.275) | −0.792 (0.718) | −0.239 (0.195) | −0.011 (0.112) | −0.069 (0.073) | 0.047 (0.080) | −0.022 (0.087) |

| (b) Treatment = 1 # Returning Instr. = 0 | −0.049 (0.030) | 23.512 (89.590) | −0.047 (0.444) | 0.086 (0.148) | 0.099 (0.082) | −0.005 (0.056) | 0.111 * (0.056) | 0.064 (0.061) |

| (c) Treatment = 1 # Returning Instr. = 1 | 0.003 (0.040) | −310.959 ** (91.156) | −0.542 (0.610) | −0.162 (0.191) | 0.031 (0.120) | 0.014 (0.073) | 0.159 * (0.077) | −0.001 (0.085) |

| (c)-(a) | 0.07 | 8.478 | 0.25 | 0.077 | 0.042 | 0.083 | 0.112 | 0.021 |

| (c)-(b) | 0.052 | −334.471 *** | −0.495 | −0.248 | −0.068 | 0.019 | 0.048 | −0.065 |

| Control Mean | 0.896 | 528.682 | 6.405 | 3.616 | −0.003 | −0.003 | 3.486 | 3.391 |

| R2 | 0.071 | 0.088 | 0.131 | 0.114 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.042 | 0.012 |

| Observations | 567 | 567 | 193 | 193 | 1611 | 7992 | 8254 | 8254 |

Notes. Standard errors in parentheses. Estimates are compared to the control group where the moderator variable is zero. The model specifications are the same as in Table 3 and Table 4, with an additional interaction term added as specified in Methods. Above we report the estimated total effect for each of the three groups, relative to instructors in the control group who were not returning instructors. The difference between point estimates are calculated with a robust Wald test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A4.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor was in the United States.

Table A4.

Treatment Effects Based on Whether the Instructor was in the United States.

| Engagement | Perception | Practice | Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Ever Viewed | Seconds Spent | NPS | Overall Perception | Wk 1 Talk Move Rate | Wk 2+ Talk Move Rate | Num. Sections Attended | Num. Assn. Completed | |

| Treatment = 0 # Instr. in US = 1 | −0.101 * (0.041) | −95.381 (82.656) | −1.444 * (0.650) | −0.363+ (0.212) | 0.222 * (0.110) | 0.114 (0.070) | −0.024 (0.070) | −0.095 (0.077) |

| (b) Treatment = 1 # Instr. in US = 0 | 0.007 (0.029) | 171.193+ (90.395) | 0.009 (0.460) | 0.094 (0.153) | 0.010 (0.092) | −0.006 (0.067) | 0.064 (0.066) | 0.035 (0.072) |

| (c) Treatment = 1 # Instr. in U.S. = 1 | −0.148 ** (0.043) | −239.925 ** (83.171) | −1.408 * (0.692) | −0.298 (0.223) | 0.390 ** (0.108) | 0.156 * (0.069) | 0.143 * (0.070) | −0.026 (0.076) |

| (c)-(a) | −0.047 | −144.544 | 0.036 | 0.065 | 0.168 | 0.042 | 0.167 * | 0.069 |

| (c)-(b) | −0.155 *** | −411.118 *** | −1.417 * | −0.392+ | 0.38 ** | 0.162 * | 0.079 | −0.061 |

| Control Mean | 0.917 | 469.458 | 6.71 | 3.683 | −0.087 | −0.087 | 3.471 | 3.417 |

| R2 | 0.067 | 0.096 | 0.131 | 0.115 | 0.031 | 0.023 | 0.043 | 0.013 |

| Observations | 567 | 567 | 193 | 193 | 1611 | 7992 | 8254 | 8254 |

Notes. Standard errors in parentheses. Estimates are compared to the control group where the moderator variable is zero. The model specifications are the same as in Table 3 and Table 4, with an additional interaction term added as specified in Methods. Above we report the estimated total effect for each of the three groups, relative to instructors in the control group who were not in the United States. The difference between point estimates are calculated with a robust Wald test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Notes

| 1 | Students were assigned to instructors prerandomization, using the following process: (1) instructors selected their preferred time slots; (2) students chose available time slots; (3) within each time slot, students were assigned to sections randomly, with one exception—instructors were sorted by age, so older students were assigned to older instructors, and underage students (<18) were never paired with adult [18+] instructors. Our study focuses only on adult instructors and their students. |

| 2 | This was the best performing cost effective GPT model available at the time of the study (spring 2023). |

| 3 | We had thought that the course would only be 5 weeks long; hence, the choice interface only had Week 5 listed for the third box. When we realized the course would be 6 weeks long, we applied their choices for Week 5 to Week 6 as well. |

References

- Anderson, L. (2010). Embedded, emboldened, and (net) working for change: Support-seeking and teacher agency in urban, high-needs schools. Harvard Educational Review, 80(4), 541–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2014). Teachers know best: Teachers’ views on professional development. ERIC Clearinghouse. [Google Scholar]

- Brod, G., Kucirkova, N., Shepherd, J., Jolles, D., & Molenaar, I. (2023). Agency in educational technology: Interdisciplinary perspectives and implications for learning design. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, K. (2021). Teacher agency in professional learning communities. Professional Development in Education, 47(4), 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, L. (2016). The power of teacher agency. The Learning Professional, 37(2), 51. [Google Scholar]

- Carter Andrews, D. J., & Richmond, G. (2019). Professional development for equity: What constitutes powerful professional learning? (Vol. 70, No. 5) SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, D. (2013). Reconceptualising and reframing graduate teaching assistant (GTA) provision for a research-intensive institution. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(2), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Mitrovic, A., & Mathews, M. (2019). Investigating the effect of agency on learning from worked examples, erroneous examples and problem solving. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 29(3), 396–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession: A status report on teacher development in the united states and abroad. National Staff Development Council. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Demszky, D., & Liu, J. (2023, July 20–22). M-powering teachers: Natural language processing powered feedback improves 1:1 instruction and student outcomes. Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S ’23), Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Demszky, D., Liu, J., Hill, H. C., Jurafsky, D., & Piech, C. (2023). Can automated feedback improve teachers’ uptake of student ideas? evidence from a randomized controlled trial in a large-scale online course. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 46(3), 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demszky, D., Liu, J., Hill, H. C., Sanghi, S., & Chung, A. (2024). Automated feedback improves teachers’ questioning quality in brick-and-mortar classrooms: Opportunities for further enhancement. Computers & Education, 227, 105183. [Google Scholar]

- Demszky, D., Liu, J., Mancenido, Z., Cohen, J., Hill, H., Jurafsky, D., & Hashimoto, T. (2021, August 1–6). Measuring conversational uptake: A case study on student-teacher interactions. 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 1638–1653), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, S., Fernandez, M.-P., Grant, D., Kaufman, J. H., Setodji, C. M., Snoke, J., Strawn, M., & Young, C. J. (2021). American instructional resources surveys: 2021 technical documentation and survey results. research report. rr-a134-10. Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C., Fishman, B., & Schoenebeck, S. Y. (2019). New contexts for professional learning: Analyzing high school science teachers’ engagement on Twitter. AERA Open, 5(4), 2332858419894252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H. C. (2009). Fixing teacher professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(7), 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, N., Fischer, C., Fishman, B., Lawrenz, F., & Eisenkraft, A. (2021). One program fits all? Patterns and outcomes of professional development during a large-scale reform in a high-stakes science curriculum. Aera Open, 7, 23328584211028601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J., Scornavacco, K., Harty, C., Suresh, A., Lai, V., & Sumner, T. (2022). Promoting rich discussions in mathematics classrooms: Using personalized, automated feedback to support reflection and instructional change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 112, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E., Dale, M., Donnelly, P. J., Stone, C., Kelly, S., Godley, A., & D’Mello, S. K. (2020, April 25–30). Toward automated feedback on teacher discourse to enhance teacher learning. 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, S., Olney, A. M., Donnelly, P., Nystrand, M., & D’Mello, S. K. (2018). Automatically measuring question authenticity in real-world classrooms. Educational Researcher, 47(7), 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. (2016a). How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. (2016b). Parsing the practice of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M. S. (1984). The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupor, A., Morgan, C., & Demszky, D. (2023). Measuring five accountable talk moves to improve instruction at scale. arXiv, arXiv:2311.10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A., & Pointer Mace, D. H. (2008). Teacher learning: The key to educational reform. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(3), 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. (2019). Roberta: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K., Hill, H. C., Gonzalez, K. E., & Pollard, C. (2019). Strengthening the research base that informs stem instructional improvement efforts: A meta-analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(3), 260–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markel, J. M., Opferman, S. G., Landay, J. A., & Piech, C. (2023, July 20–22). GPTeach: Interactive ta training with GPT based students. Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S ’23), Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L. E., Kragler, S., Quatroche, D., & Bauserman, K. (2019). Transforming schools: The power of teachers’ input in professional development. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 9(1), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B. (2001). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(89), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Nezhad, P., & Stolz, S. A. (2024). Unveiling teachers’ professional agency and decision-making in professional learning: The illusion of choice. Professional Development in Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]