‘I Did Not Choose Teaching Because…’: Examining the Underrepresentation of Ethnic Minority Teacher Candidates in Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the perception of the teaching profession among people from ethnic minority backgrounds?

- What inhibits people from ethnic minority backgrounds from considering teaching as a career?

- What would have motivated people from ethnic minority backgrounds to consider teaching?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Lack of Role Models

2.2. Constrained by Culture and Family Expectations

2.3. Poor Perception of the Teaching Profession

2.4. Negative Self-Concept

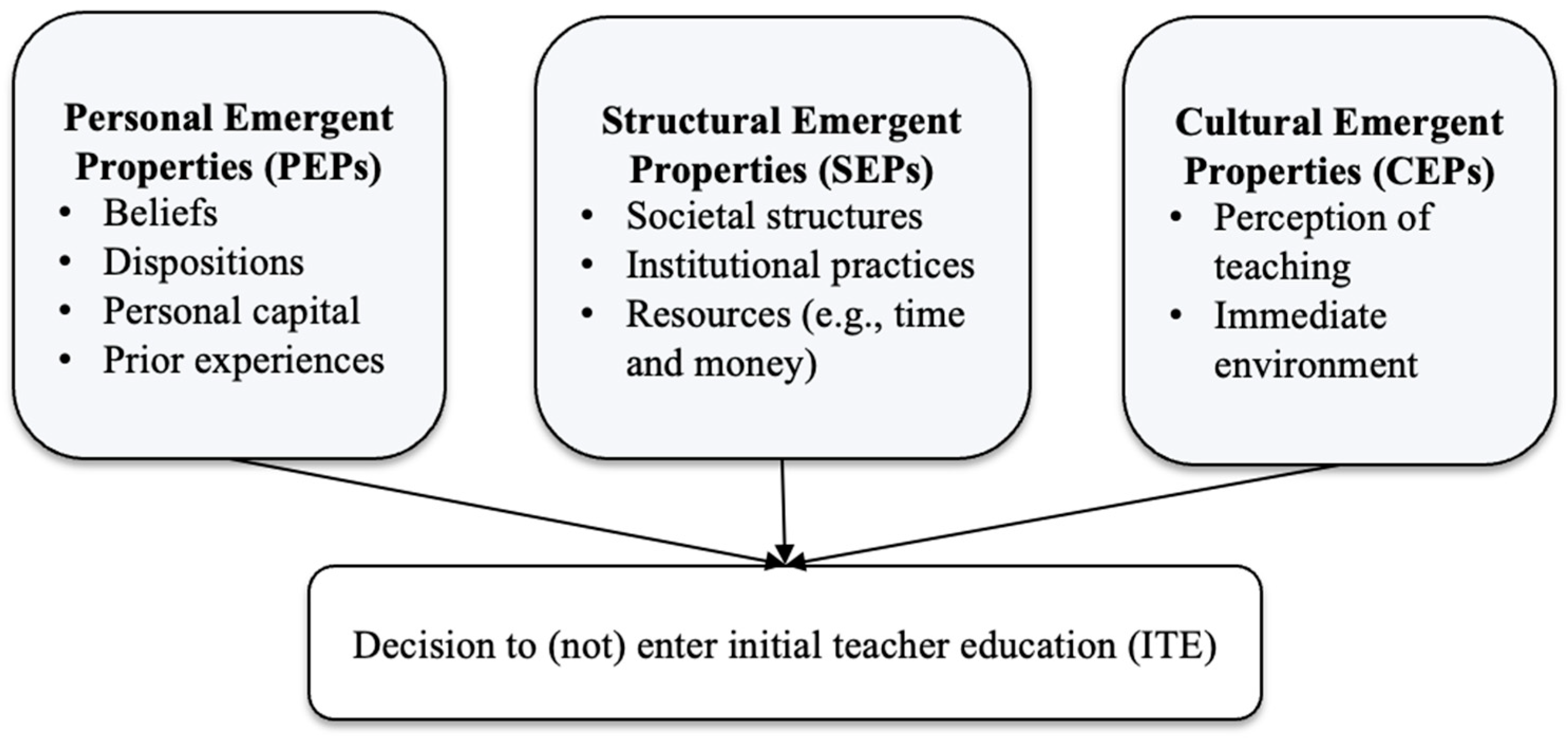

3. Theory of Reflexive Decision-Making

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

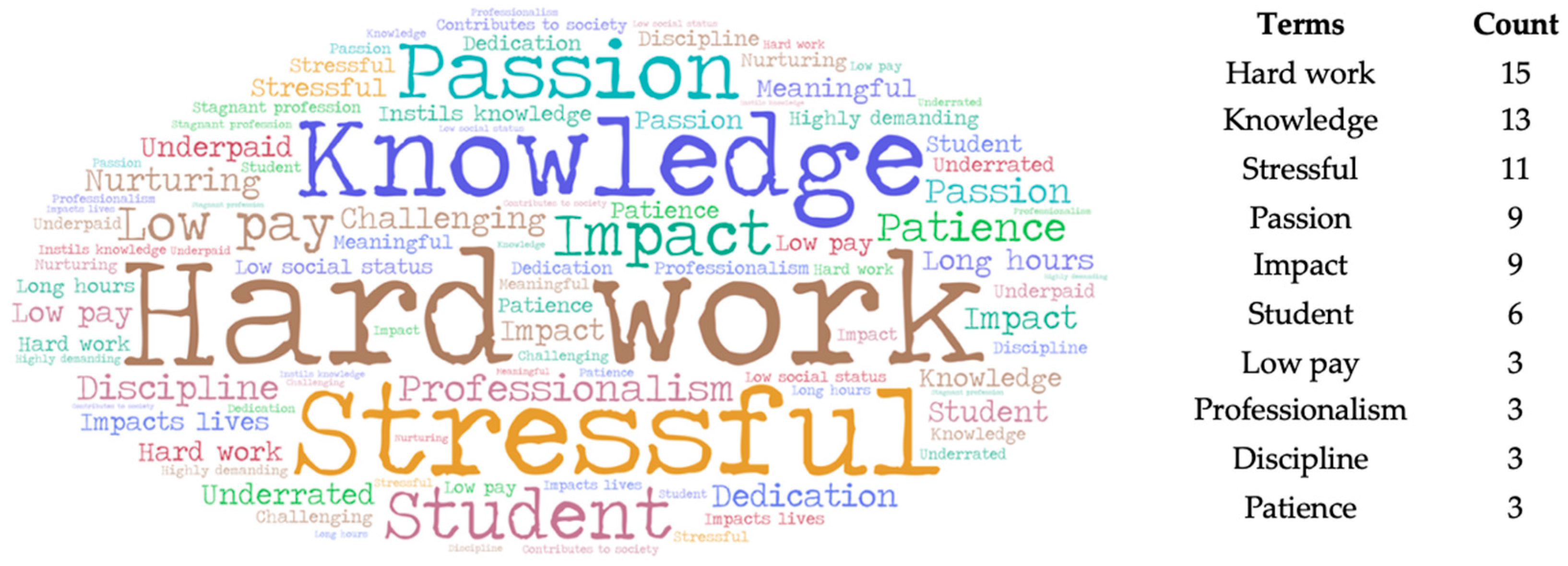

5.1. What Is the Perception of the Teaching Profession Among People from Ethnic Minority Backgrounds?

5.2. What Inhibits People from Ethnic Minority Backgrounds from Considering Teaching as a Career?

5.2.1. Theme 1: Personal Beliefs

Unsuitable Personality Traits

Lack of Confidence

5.2.2. Theme 2: Racism and Discrimination

Stereotype

“I was in Year 10. We had a one-to-one session with the career counsellor to discuss where we should go for further studies after we finish high school. When I entered the room, the counsellor, a white man, looked at me and immediately took out the course brochures for TAFE1. He didn’t even ask me if I was going to university. In fact, my results are quite good, and I am studying an engineering course now. Just because I am black, he assumed that my results were not good and that I could not make it into university”.(FG 1)

Exclusion

5.2.3. Theme 3: Financial Consideration

Low Teacher Salary

Low Return on Investment

5.2.4. Theme 4: Career Pathway

Limited Career Progression

5.2.5. Theme 5: Status and Image of Teaching

Low Status of Teachers

Lack of Recognition

“Recognition for teachers varies, but I feel they don’t always receive the level of recognition they deserve. Teaching is a demanding profession that involves shaping the next generation’s future. Yet, factors like low salaries, high workloads, and societal misconceptions can contribute to the perception that teachers are undervalued.”

5.2.6. Theme 6: Social Influence

Discouragement from Important Others

5.3. What Would Have Persuaded People from Ethnic Minority Backgrounds to Consider Teaching?

6. Discussion

6.1. Personal Emerging Properties (PEPs)

6.2. Structural Emerging Properties (SEPs)

6.3. Cultural Emerging Properties (CEPs)

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | TAFE is the acronym for technical and further education. It is the vocational education pathway for students who do not plan to further their study in a university. |

References

- Allen, J., Rowan, L., & Singh, P. (2019). Status of the teaching profession—Attracting and retaining teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(2), 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvariñas-Villaverde, M., Domínguez-Alonso, J., Pumares-Lavandeira, L., & Portela-Pino, I. (2022). Initial motivations for choosing teaching as a career. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 842557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, M. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. (2022). Next steps: Report of the quality initial teacher education review. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Australian Government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2022). Incentivising excellence: Attracting high-achieving teaching candidates. Available online: https://behaviouraleconomics.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/projects/incentivising-excellence-full-report.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2021). Teaching futures. Background paper. Education Services Australia. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/ait1793_teaching-futures_fa(web-interactive).pdf?sfvrsn=d6f5d93c_4 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Australian Teacher Workforce Data. (2021). National teacher workforce characteristic report. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/national-teacher-workforce-char-report.pdf?sfvrsn=9b7fa03c_4 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Australian Teacher Workforce Data. (2022). Preliminary workforce characteristics 2021–2022 and trends in the workforce 2018–2020. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/atwd-teacher-workforce-report-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=126ba53c_2 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Bahr, N., Pendergast, D., & Ferreira, J. (2018). Teachers are not under-qualified and not under-educated: Here’s what is really happening. EduResearch Matters. Available online: https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=3197 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Bardach, L., Rushby, J. V., & Klassen, R. M. (2021). The selection gap in teacher education: Adverse effects of ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status on situational judgement test performance. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Calitz, A. P., Cullen, M., Twani, M., & Fani, D. (2022, September 25–27). The role of culture in first year student’s career choice [Conference session]. 15th International Business Conference, Summer West, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Dolton, P., & Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2011). If you pay peanuts do you get monkeys? A cross-country analysis of teacher pay and pupil performance. Economic Policy, 26(65), 5–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M. (2023). Against the odds: A study into the nature of protective factors that support and facilitate a sample of individuals from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds into the teaching profession. Journal of Education for Teaching, 50, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fray, L., & Gore, J. (2018). Why people choose teaching: A scoping review of empirical studies, 2007–2016. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, H. A., & Ramirez, N. (2015). Why race and culture matters in schools: Closing the achievement gap in America’s classrooms. The Journal of Negro Education, 84(1), 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P., Sonnemann, J., & Nolan, J. (2019). Attracting high achievers to teaching. Grattan Institute. Available online: https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/921-Attracting-high-achievers-to-teaching.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Griffin, A. (2018). Our stories, our struggles, our strengths. The Education Trust. Available online: https://edtrust.org/resource/our-stories-our-struggles-our-strengths/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). The distribution of teacher quality and implications for policy. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, A., Longmuir, F., Bright, D., & Kim, M. (2019). Perceptions of teachers and teaching in Australia. Monash University. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/perceptions-of-teaching/docs/Perceptions-of-Teachers-and-Teaching-in-Australia-report-Nov-2019.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Hilton, A. L., & Saunders, R. (2023). LANTITE’s impact on teacher diversity: Unintended consequences of testing pre-service teachers. Australian Educational Researcher, 51, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, K., Bodle, K., & Miller, A. (2018). Opportunities and resilience: Enablers to address barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to commence and complete higher degree research programs. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2018(2), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewalramani, S., & Phillipson, S. (2020). Parental role in shaping immigrant children’s subject choices and career pathway decisions in Australia. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(1), 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C., & Coulthard, M. (2018). Undergraduates’ views of teaching as a career choice. In P. Gilroy (Ed.), The journal of education for teaching at 40 (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landertinger, L., Tessaro, D., & Restoule, J. (2021). ‘We have to get more teachers to help our kids’: Recruitment and retention strategies for teacher education programmes to increase numbers of Indigenous teachers in Canada and abroad. Journal of Global Education and Research, 5(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maire, Q., & Ho, C. (2024). Cultural capital on the move: Ethnic and class distinctions in Asian-Australian academic achievement. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 33(1), 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Köller, O. (2004). Unification of theoretical models of academic self-concept/achievement relations: Reunification of East and West German school systems after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 29(3), 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, D., & Murphy, D. (2016). Understanding accounting as a career: An immersion work experience for students making career decisions. Accounting Education, 25(1), 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockler, N. (2022). Constructing teacher identities: How the print media define and represent teachers and their work. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombaers, T., Van Gasse, R., Vanlommel, K., & Van Petegem, P. (2023). ‘To teach or not to teach?’ An exploration of the career choices of educational professionals. Teachers and Teaching, 29(7–8), 788–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 results (Volume II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Raising the attractiveness of a career in schools. In working and learning together: Rethinking human resource policies for schools. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patfield, S., Gore, J., & Weaver, N. (2022). On ’being first’: The case for first-generation status in Australian higher education equity policy. Australian Educational Researcher, 49(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S., Garner, A., & Graham, L. (2023). Seeing ourselves at school: Increasing the diversity of the teaching workforce. A jack keating policy paper. University of Melbourne. Available online: https://education.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/4767545/ONLINE-RFQ08427-MGSE-DiversifyingTeachers-v7-Online.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Scottish Government. (2018). Teaching in a diverse Scotland: Increasing and retaining minority ethnic teachers in Scotland’s schools. Scottish Government. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2018/11/teaching-diverse-scotland-increasing-retaining-minority-ethnic-teachers-scotlands-schools/documents/00543091-pdf/00543091-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00543091.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- See, B. H., Elaine, M., Ross, S. A., Hitt, L., & Soufi, N. E. (2022). Who becomes a teacher and why? Review of Education (Oxford), 10(3), e3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C., & Aston, K. (2024). Ethnic diversity in the teaching workforce: Evidence review. National Foundation for Educational Research. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED648293.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Silva, A. D., & Taveira, M. D. C. (2025). Aspirations for teaching career: What we need to know and what we need to do. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1525153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (2016). Racism and everyday life: Social theory, history and “race” (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G., McDonald, S., & Stokes, J. (2020). ‘I see myself as undeveloped’: Supporting Indigenous first-in-family males in the transition to higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1488–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, A., & George, S. (2021). Teacher education is a good choice, but I don’t want to teach in schools. An analysis of university students’ career decision making. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(4), 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S. Y. (2025). Asian immigrant teachers in Australia: Negotiating identity, navigating adaptation, and the paradoxes of belonging (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A. (2022, December 12). Four in ten ethnic minority workers have hidden career choices for cultural reasons. The Mirror. Available online: https://www.mirror.co.uk/money/jobs/ethnic-minority-workers-cultural-expectations-28715830 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

| # | Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Personal beliefs | Unsuitable personality traits Lack of confidence |

| 2 | Racism and discrimination | Stereotype Exclusion |

| 3 | Financial consideration | Low salary Low return on investment |

| 4 | Career pathway | Limited career progression |

| 5 | Status and image of the teaching | Low status of teachers Lack of recognition |

| 6 | Social influence | Discouragement from important others |

| Theme: Status and image of teaching | 35% * |

| Sub-themes: | |

| Positive image of teachers in the society | 10% |

| Public recognition of teachers’ work and contribution | 10% |

| Higher social status in the society | 9% |

| Stronger publicity and recruitment drive to join the profession | 6% |

| Financial incentives | 31% |

| Sub-themes | |

| Government initiative to increase the salaries of teachers | 11% |

| Teaching scholarships/stipends for teacher education degree | 11% |

| Reduction in tuition fees for teacher education degree | 9% |

| Career pathway | 24% |

| Sub-themes | |

| Guaranteed jobs after graduation | 9% |

| Clear career progression and promotion pathway | 8% |

| Opportunities to try out teaching before deciding to enrol in ITE | 7% |

| Social influence | 11% |

| Sub-themes | |

| Encouragement from family members | 6% |

| Encouragement from people who are teachers | 5% |

| Personal Emerging Properties (PEPs) | Structural Emerging Properties (SEPs) | Cultural Emerging Properties (CEPs) |

|---|---|---|

Personal beliefs

| Racism and discrimination

| Status and image of teaching

|

Financial consideration

| ||

Career pathway

| Social influence

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yip, S.Y.; Xu, Y. ‘I Did Not Choose Teaching Because…’: Examining the Underrepresentation of Ethnic Minority Teacher Candidates in Australia. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091163

Yip SY, Xu Y. ‘I Did Not Choose Teaching Because…’: Examining the Underrepresentation of Ethnic Minority Teacher Candidates in Australia. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091163

Chicago/Turabian StyleYip, Sun Yee, and Yue Xu. 2025. "‘I Did Not Choose Teaching Because…’: Examining the Underrepresentation of Ethnic Minority Teacher Candidates in Australia" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091163

APA StyleYip, S. Y., & Xu, Y. (2025). ‘I Did Not Choose Teaching Because…’: Examining the Underrepresentation of Ethnic Minority Teacher Candidates in Australia. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091163