Abstract

STEM ideologies provoke environmental destruction from which deaf, disabled, and Indigenous people are uniquely targeted. Our analysis counteracts harms caused by governmental, industrial, and educational agents who weaponize STEM ideologies against downstream people, animals, plants, environments, and biogeochemical entities. We explore two research questions via a theoretical framework about biocultural deaf gains and deaf/Indigenous languacultures to center the arts in STEAM. As a result, we synthesized a conceptual framework called Deaf and Indigenous Curricula and Eco-pedagogies (DICE), which are multimodal, multilingual approaches to STEAM education emphasizing place-based ecology and the arts, including knowledge emanating from Indigenous Deaf Cultures, Indigenous sign languages, and epistemologists who are deaf, disabled, women, and Indigenous (singly or in combination). DICE is designed to reinvigorate communities and ecologies at risk of destruction from colonialism and runnamok capitalism. Within and across Indigenous and Deaf lifeworlds, our model explores: collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis. These are situated in examples drawn from the research, abductive reasoning, our life histories, and the creative works of Deaf Indigenous scientists and artists. In sum, alongside uprising Indigenous voices, deaf hands shall rise in solidarity to aid Earth’s defense.

1. Introduction: STEM Weaponized

The Earth is not dying. It’s being killed (Cajete, 2000; Morton, 2016).

Ecological collapse is interwoven with the human biome (Orr et al., 2024), colonialism, (Tuhiwai Smith, 2022) and capitalism in decay (de Alba et al., 2000; Bertling, 2023; Haraway, 2015). Mankind is the cause of this destruction and now victim to it. Catastrophic entropy is evidenced by collapsing global fisheries, biodiversity loss in Amazonas, and wildfire-scorched Siberian taigas, now releasing long-dormant pathogens (Orf, 2024).

Ecological collapse spans the Global North and South, burdening human and more-than-human systems indiscriminately (Laville, 2020; Orr et al., 2024; Rees, 2019), from coal rolling to coral bleaching, from firebombs to Nagasaki.

History shows that human obliteration often begins with vulnerable and marginalized people; those who are disabled, poor, Black, Brown, and Indigenous (Tuck & Yang, 2012; Zinn, 1980/2003). Understand this: capitalism and colonialism are engines of disability that exploit environmental destruction (Konrad, 2024; Puar, 2013). Ecocide is enabled through the weaponization of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). When STEM ideologies are weaponized through education, research, industry, and government, “scientific progress” provides cover for expanding capitalism and colonialism against these and other marginalized people worldwide (Puar, 2013; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022).

Ecocide contributes to amorphous genocides against Indigenous peoples worldwide (Bacca, 2019; Charles & Thomas, 2007; Reyes-García et al., 2024). Ecocide and genocide are distinct but often co-occurring forms of widespread death. Concurrently, disabled people, including Indigenous Deaf persons, in Asia, Europe, and the Americas are disproportionately at risk from climate change, industrial chaos, and ecological degradation (Charles & Thomas, 2007; Jaffee & John, 2018). Examples clarify a nauseating reality: First, DuPont’s Teflon—one of several hundred forever chemicals—is found in 99% of human bodies; Teflon cannot be metabolized and inculcates cancers in mothers, children, and elderly people (Dark Waters, 2024). Second, “In a textbook horror-story of global capitalism, on 3 December 1984, the U.S. owned Union Carbide pesticide factory spewed forty tons of lethal toxic methyl isocyanate [on] Bhopal in India. Nearly 10,000 people died and 30,000 people were disabled overnight” (Pandya, 2023, n.p.).

In response to ecological catastrophe, we synthesize a novel conceptual framework called Deaf and Indigenous Curricula and Eco-pedagogies. DICE is our generative approach to cross-coalitional solidarity against ecocide and genocide. Our framework criticizes dominant discourses in STEM education. Our analysis also reveals systematic exclusion of deaf, disabled, and Indigenous people working for ecological justice in STEM education (C. A. Bowers, 2001; Mangan, 2023; Ross et al., 2019; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). As we argue, this exclusion is deliberate and egregious; however, it opens an opportunity to generate new knowledge (D. M. Bowers et al., 2024; Gutiérrez, 2022; Hussain, 2024).

Our framework centers artistic and creative works produced by deaf and Indigenous epistemologists (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; McKay-Cody, 2024) and explores the transformative roles of culture, language, and artforms (e.g., languacultures), which are often absent in STEM discourses. From an aesthetic vantage, we explore the role of the arts in ecological education (de Alba et al., 2000; Bertling, 2023), Native cosmologies and pedagogies (Cajete, 2000; Grande, 2015; Sams & Carson, 1988), and place-based pedagogical and curricular frameworks in STEM (Gutiérrez, 2022; Nicol et al., 2023a, 2023b; Thom, 2019). These are examined alongside authentically anti-colonial and decolonial research methodologies (Tuck & Yang, 2012; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). By analyzing contributions from these epistemologists, our DICE model explores three main themes: collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis.

Throughout our analysis, we explore two core questions about biocultural deaf gains and languacultures: How do Deaf and Indigenous people create knowledge that entangles ecology, languacultures, and STEAM pedagogies and curricula? How might the DICE conceptual framework unfurl in schools, and what may come from doing so?

2. Theoretical Framework: Hybridizing Epistemologies

We categorized then juxtaposed four primary bodies of knowledge. First, we consulted literature on Indigenous epistemologies from forest shamans, tribal elders, and practitioners of Animal Medicine (Cajete, 2000; Sams, 1990; Semali & Maretzki, 2004). Second, we analyzed deaf epistemologies from deaf cultural workers, artists, and researchers of sign linguistics and deaf studies (Cue et al., 2019; De Clerck, 2017; Schiff, 2010; Wang, 2010; Weber, 2020a). Third, we examined STE(A)M research about pedagogies and curricula adapted for deaf learners from diverse language and cultural backgrounds (Adler, 2025; Bradi et al., 2023; Henderson et al., 2023; Lang, 2016; Pagliaro & Kurz, 2021). Fourth, we explored research about Indigenous Deaf epistemologies, including educational, cultural, and scientific knowledge (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; McKay-Cody, 2024; Musengi, 2023; Musengi & Musengi, 2024; Sherley-Appel & Bonvillian, 2014).

Our framing does not explore these categories discretely. Instead, we juxtapose them to synthesize three theories most germane to the DICE conceptual framework: biocultural diversity (Bauman & Murray, 2014), the arts in deaf educational languacultures (Agar, 1980), and the importance of Indigenous Animal Medicine (Buenaflor, 2021; Sams & Carson, 1988) in the fight against ecocide.

2.1. Indigenous and Deaf Biocultural Diversity

2.1.1. Deafness and Indigeneity Are Reciprocal Umwelten

Being deaf is a dynamic mode of being human. Deaf ontology is partly defined by an absence of hearing (Bauman & Murray, 2014). Being deaf is relational (Leigh et al., 2023). Deaf people positively adapt lifeways and epistemologies toward deafness (Holcomb et al., 2020; Vygotsky, 1993), including compensatory adaptations using visual sign languages by deaf sighted people, tactile sign languages by deaf and blind people, and technosocial adaptations by disabled deaf people (Guardino et al., 2022; Skyer, 2023a). In contemporary terms, deaf ontological gains sustain deaf epistemological gains. That is, being deaf produces deaf educational knowledge forms (Cue et al., 2019; Kress, 2010; Skyer, 2023b).

Deaf gain is an axiology bent toward deafness (Bauman & Murray, 2010, 2013, 2014). Deaf gain proposes that being deaf is inherently good. One category is intrinsic deaf gains, in which deaf people direct themselves or members of their communities to solve problems. An example is intergenerational deaf pedagogy (Kusters, 2017), where deaf adults teach deaf children in culturally sustaining, cognitively appropriate ways. Extrinsic deaf gains illuminate deaf people’s contributions to general knowledge and in support of macrostructural human-ecological coherence (Skyer, 2015). Seen this way, being deaf is a wellspring for human creativity uniting ecology, arts, sciences, and education.

Deaf gains result in unique forms of cognition (Calton, 2014; Hauser & Kartheiser, 2014; Petitto, 2014). Deaf ontology can be understood as an umwelt—a term coined by Uexküll (see Jones et al., 2021, p. 247)—which refers to an organism’s total sensory milieu within an environment. A deaf-positive stance about cognition suggests that deaf umwelten permit an abundance of visual, tactile, and kinesthetic ways of knowing in the world (Moody, 2002). “Deaf corporeality and the social environments of deaf education are integrated in the deaf umwelt, whose dimensions are ecologically structured and relative. Biosocial deaf education is an ecology of agents working collaboratively to mutually develop the deaf umwelt.” (Skyer, 2021, p. 49).

Incipient in deaf gain theory is the seed of an idea that we aim to germinate presently. Deaf biocultural diversity situates deaf people as “collectivist global citizens [coexisting in] deep, intersubjective reciprocity” with other denizens of Earth (Bauman & Murray, 2014, p. xxxiii). Throughout the rest of our analysis, we work to develop this intersubjective reciprocity and coexistence at a global scale.

2.1.2. Indigenous Deaf Gains Exist

Indigenous peoples possess longstanding ties to the land and share geo-historical lifeways among tribal groups (i.e., Cherokee, Seminole, Cheyenne, etc.) (Cajete, 2000; McKay-Cody, 2019). Indigeneity presupposes an ontological concept of “origin.” Native and Indigenous alongside Aboriginal are commonly used terms, with differing histories, imbued with respect and denoted with capitalization (Dunbar-Ortiz & Gilio-Whitaker, 2016; Kovach, 2021). Shotton et al. (2013), explain, Indigenous people are ethnic minorities and “members of sovereign nations and political groups” (2013, p. 4). Indigenous is an adjective that indicates cultural lifeways of a tribe and their relationship to natural things. For instance, maize (corn) is indigenous to the Americas, as are potatoes, tomatoes, and cocoa.

Deaf gain, deafness, and Indigeneity are not mutually exclusive (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; McKay-Cody, 2024). Indigeneity is canonical to deaf gain (Sherley-Appel & Bonvillian, 2014), including Indigenous communities with a high prevalence of deafness (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014), like Bedouin (Kisch, 2007; Senghas, 2005) and Inuit tribes (Sherley-Appel & Bonvillian, 2014). As Adams and Gilroy (2024) write,

‘Deaf Gain’ was embedded in many traditional Indigenous communities and the importance of the revitalization of Indigenous sign languages [is] crucial to cultural continuity…the concept of Deaf Gain is, at its core, empowerment for people who are deaf, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous.(pp. 139–140)

2.2. Languacultures

2.2.1. Multimodal-Multilingual Deaf Education Is Biosocial

Humans are biological, social entities. We learn and teach using our bodies and minds, which are situated in knowledge as languages and cultures (Chomsky, 2015; Vygotsky, 1993). There can be no authentic teaching or learning theory in the absence of diverse human ontologies, languages, and cultures (Skyer, 2023a; Vygotsky, 1993). As Ortega (2009) points out, outside a social framework for education, nothing can be known.

Languacultures are the Petri dish growing human creativity. Languacultures collocate languages and cultures (Agar, 1980). Languacultures foster human developments via arts, letters, and sciences (Languaculture, 2023), including multicultural solidarity in deaf STEAM education (Gomes & Locatelli, 2024). From intact languacultures, critical masses of humans—disabled and not, Indigenous and not—coexist, grow, learn, and teach with uncoerced reciprocity (Bookchin, 1982/2005). The deaf education languacultures we champion are biosocial, multilingual, multimodal, multicultural, and multiracial/ethnic (Golos et al., 2023; Skyer, 2023a). Deaf languacultures sustain STE(A)M education and overtly value deaf pedagogies and curricula that are multilingual and uplift threatened and minoritized sign languages (J. Scott et al., 2023). We believe that a multiplicity of languages and cultures is important, but by themselves, are not enough. We champion multimodality because multimodality capacitates the widest range of knowledge forms (Kress, 2010) and innate abilities, which burgeon like seeds in diverse deaf people (Skyer, 2023c).

Vulnerable minorities in deaf spaces can be harmed without active work against sources of harm. Our stance explicitly values and seeks to revitalize a multiplicity of threatened Indigenous and Deaf languacultures, including multiple sign languages (McKay-Cody, 2024; Mitchell, 2024; UNESCO, 2024). Our stance is in line with current research in deaf education (J. Scott et al., 2023), Black and Brown pedagogies (Paris & Alim, 2014), Indigenous pedagogies (Perez & Vásquez, 2024), and deaf Indigenous pedagogies (Musengi, 2023). DICE’s languaculture is inherently multilingual, multimodal, situated, arts-based and place-based. DICE is concerned with material conditions, bodies, biosocial ecologies, with natural environments, and their total interdependence. DICE is critical of unequal power relations and seeks to redistribute power, knowledge, and material resources from those who hoard power to those whose power has been expropriated.

2.2.2. Languacultures and Arts Breathe Life into STE(A)M Education

STEM Education refers to teaching and learning about science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. STEM encompasses subfields like biology, calculus, and geology, among others (Solomon & Aikenhead, 1994). The addition of “A”—the arts—into the matrix of STEM is a critical point of entry for us to examine dilemmas about the role of axiology (e.g., ethics and aesthetics, ideology), as well as arts and languacultures. For us, the arts are transformative (not additive) with respect to STEM. Western arts-based languacultures include media like sculpture, performance, installation, bio art, language arts, and digital technologies (Bertling, 2023; Jones et al., 2021). Beyond the Western canon are arts from Indigenous languacultures. For instance, Indigenous people have unique ways of representing scientific and cultural knowledge-forms, such as shamanism (Abram, 1997), Wampum beading, and Animal Medicine (Sams & Carson, 1988). For Indigenous Deaf people, this includes Hand Talk, petroglyphs, and ceremonial dance that represent knowledge emanating from the natural world (McKay-Cody, 2019, 2024).

2.3. Animal Medicine

Animal Medicine is an Indigenous practice of divination (Erdoes & Ortiz, 1984), which includes interpretations of “the sacred power received by a human person from a particular animal” (Abram, 1997, p. 275). We approach our interpretive task with joyful wonder as we gaze on the infinite creativity of the Great Mystery (Cajete, 2000).

We embrace the joyful, miraculous energies of this iridescent Hummingbird feather. Hummingbird radiates the spectrum of love. Unable to be held captive, “Hummingbird energetically embraces the highest aesthetics […] Hummingbird [will spread] joy [or] be destroyed.” (Sams & Carson, 1988, p. 214). Of the two, we evoke joy as the means to avoid destruction. Likewise, we meditate on the convoluting energy of this Black Vulture skull, whose spiritual body is lifted by the rising breath of Earth. Vulture spirit teaches higher wisdom (Buenaflor, 2021). Oft disdained for its predilection for carrion, in Indigenous traditions, Vulture is purifying. Vulture keeps ecologies healthy by cleansing the Earth. Frank and Sudarshan (2024) describe Vulture as a keystone species—their absence appreciably increases human mortality.

The joy of Hummingbird and metamorphosis of Vulture give us a higher vantage to observe ruinous calamity and perhaps the wisdom to avert it. As Morton (2016) explains: “The ecological era we find ourselves in—whether we like it or not and whether we recognize it or not—makes necessary a searching reevaluation of philosophy, politics, and art” (p. 159). To this we add that STEAM disciplines, their pedagogies, curricula, and ideologies demand autopsy. As Weber (2020a) shows, Indigenous Deaf youth can explore human languacultures and more-than-human ontologies through animal wisdom. Thus, embracing biocultural diversity, Indigenous Deaf languacultures, Hummingbird and Vulture medicine, we inaugurate a joyful cleansing to identify sources of harm, break their stranglehold, and welcome new modes of beneficence to bring about positive transformations of Earth and all its inhabitants.

With joy and wonder, we call on Animal Medicines to give us succor against the lengthening odds of impending catastrophe. We refuse collapse. We counter with light, laughter, and optimism.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

Our first question has four prongs: How does being deaf and being Indigenous contribute to producing knowledge about: (a) Earth’s environmental/symbiotic complexity, (b) human cultural milieux, aesthetics, and artforms, (c) STE(A)M pedagogies and curricula, and (d) rhizomatic entanglements thereof? Our second research question has two parts: How might the DICE conceptual framework be implemented, and what potential opportunities and challenges may arise from its operationalization?

Responses to the first question (See: Section 4—Literature Synthesis) are theoretical. We emphasize practical applications when responding to the second question (See: Section 5—Discussion). While we aim for plausible answers, we also offer more questions than answers. Questions, we think, are a legitimate method for wayfinding amid uncertainty. We acknowledge that more research is essential. We invite readers to work with us, explore our concepts, and adapt DICE to situated needs and local contexts.

3.2. For Whom We Write and Why

The DICE framework may guide theory and practice in and beyond deaf and Indigenous Deaf STEAM education. We primarily write for theorists and philosophers of deaf research; this is reflected in our methods and representation of findings through elements of Indigenous art, strong rhetoric, and narratives about languacultures in deaf spaces. Our secondary audience includes students, teachers, and professors in deaf education, who we hope will integrate our ideas, if deemed useful, into their pedagogies and learning habits. Our work combines deep theorization with empirical substantiation when available. To grow a scant research base, we include lessons from our life histories as learners, teachers, and researchers. Overall, DICE aims to counter ecocide and reverse the destitution of material resources that uniquely and disproportionately harm marginalized peoples, including Indigenous, deaf, and disabled communities worldwide.

3.3. What We Did and Why It Matters

3.3.1. Literature Synthesis

We conducted a literature synthesis that is generative, critical, conceptual and is interfaced with abductive reasoning; in this section we describe our methods in relation to these methodological terms (Barnett-Page & Thomas, 2009; Timmermans & Tavory, 2012).

Our synthesis is generative (Boote & Beile, 2005). We not only summarize prior studies, we propose substantive ideas into the knowledge base because there are many strands we wished to braid amid a profusion of gaps in prior work. By critical we mean our analysis is not ideologically neutral toward deafness, Indigeneity, or ecology (McCarty & Lee, 2014; McKay-Cody, 2024; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014). Nor do we pretend to be disinterested in the subjects we explore, the communities we are part of, or the politico-ethical views we advance (Lather, 2001; Guba & Lincoln, 1994; Kincheloe et al., 2018). Furthermore, by conceptual, we distinguish between a priori theoretical framing (e.g., deaf gain), and the novel conceptual framework, where DICE is broader in scope and required active theory-construction (Imenda, 2014; Upadhayay, 2018).

Building our framework required abduction, which is an empirically based method for producing new insights, hypotheses, or frameworks. Abduction seeks explanation (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). Abduction allows for creative inferential processes alongside iterative critical analysis and theoretical evaluation (Dilworth, 2015). We worked to integrate previously unconnected ideas with novel insights (Cresswell, 2012; Marshall & Rossman, 2016). As Peirce (1934) writes, “Abduction is…the only logical operation which introduces any new ideas” (cited in Timmermans and Tavory (2012, p. 171)). Abduction was essential to support our analysis and enabled us to productively explore and evaluate the literature, synthesize prior studies with our creativity, as informed by our prior knowledge, experiences, and abilities (Dodgson, 2021).

Our goal is to introduce DICE as an orientation for STEAM education across subfields and populations by focusing on arts and languacultures. This stance builds on arts-based innovations outside deaf education (Bertling, 2023), but we uniquely emphasize how deaf arts-based STEAM research can advance ecological axiology through education. While it is known that arts-based education supports creativity and communication for deaf students (Skyer, 2023c), the arts are under-used and undertheorized in deaf STEM research. Differently, scholarship about Indigenous onto-epistemologies foregrounds harm caused to humans and more-than-human entities by colonization and STEM ideologies (de Alba et al., 2000; Cajete, 2000; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). Likewise, Deaf Indigenous research calls attention to the threats of ecocide and cultural imperialism through education (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; Aronowsky, 2021; McKay-Cody, 2024; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014). Within this nexus, we advance the idea that Indigenous Deaf people’s creative products are scientific artforms (McKay-Cody, 2019) that can address ecocide and genocide through STEAM education (Arellano, 2024).

3.3.2. Procedures and Products

Our goal was to synthesize knowledge (Barnett-Page & Thomas, 2009; Boote & Beile, 2005) and produce a novel, coherent, and rigorous conceptual framework (Hong & Pluye, 2019; Ravitch & Riggan, 2016). Literature Synthesis aligns DICE with our intended audiences. As Barnett-Page and Thomas (2009) write,

The outputs of synthesis methods [are] generally more complex and conceptual, sometimes operating on the symbolic or metaphorical level, and requiring a further process of interpretation by policy makers and practitioners [to] inform practice. [Synthesis methods are most useful for] other researchers and theoreticians.(p. 59)

We synthesized credible studies regardless of methodology (Mertens, 2020). Unlike meta-analysis (systematic quantitative reviews) or meta-synthesis (systematic qualitative reviews), our synthesis does not compartmentalize evidence; instead, we used critical appraisal to prioritize insightfulness (Dodgson, 2021; Hong & Pluye, 2019).

We followed Dodgson’s (2021) model of critical literature reviews, emphasizing three stages: deconstruction, analysis, and reconstruction. Our searches were iterative, relying on both authors’ areas of expertise, peer reviewer comments, and editorial suggestions. For instance, studies deemed unethical with respect to Indigenous Deaf people were excluded (McKay-Cody, 2024). Deconstruction and analysis asked us to disassemble and evaluate studies based on methodologies, theoretical frames, and evidence. Reconstruction happened as we built the DICE framework and wrote and edited our article, where we harmonized findings and paid attention to aesthetics and transparent representation, especially with respect to the researcher’s currere (Pinar, 1975), or positionality.

3.4. Positionological Analysis

Transparent positionality analysis is necessary in deaf research (Cawthon & Garberoglio, 2017, 2021; Graham & Horejes, 2017). Positionology assists readers in judging the quality of findings and the suitability of the research team for the task at hand. Below, we discuss our positionalities through experiential vignettes. Readers may wish to know that the initial proposal was crafted by Skyer but that the full manuscript was developed by Skyer and McKay-Cody. Skyer is a man, bisexual, deaf, and multiply-disabled. On apt editorial advice, Skyer sought out McKay-Cody as a writing partner. McKay-Cody is a woman, Indigenous, deaf, and a tribal elder. Our partnership resulted in many excellent exchanges of knowledge exceeding the scope of the present manuscript.

3.4.1. Skyer

Skyer is not Indigenous. He is a grandson of diasporic immigrants of Irish, Polish, and French-Canadian extraction. Skyer is an avid student of Indigenous epistemologies. He first learned Native wisdom at an early age from a Cherokee family friend who provided spiritual guidance in American Sign Language (ASL), and whose spouse is deaf, and children are CODAs. Skyer has continuously taught in deaf education since 2007. Skyer’s PhD is in education. He researches pedagogies and curricula adapted by deaf people who are gender/sexuality minorities, ethno-racial minorities, or multiply disabled minorities. Both vignettes explore his teaching with deaf and disabled communities.

Vignette One

I (Skyer) was working in a preschool special education unit with disabled children. I was a learner of pedagogy learning about curriculum. In other words, I was apprenticing my trade. Following a unit on undersea life, the lead teacher and I designed a “craft” project intended to look like jellyfish. The projects used cheap Styrofoam bowls, adorned with colorful nylon yarn, and painted with acrylics. Following the day’s work, the “jellyfish” ended up in the trash because the plastic paint flaked off the synthetic foam. As it flaked, it coated the hands of the students before we helped them wash away the microplastics into the classroom sink (and perhaps the local waterways). This STEM unit, ostensibly about ecology, polluted its subject. While my multimodal enthusiasm was evident, in my haste, I contributed to harm.

Vignette Two

I was a lead teacher in a deaf education residential school unit. While I worked as an English teacher in the high school, myself and two other teachers (one an upper-school science teacher, and the other an elementary teacher), wrote and submitted a micro-grant. To our surprise, it was funded by a local municipal waste corporation. At culmination, our modest grant funds helped us explore a nearby forest preserve and to plant native tree species on the campus grounds. We conceptualized our teaching as intergenerational. We taught high school-aged deaf and disabled students to become teachers, who, in turn instructed younger deaf children about ecological concepts. The older disabled deaf students modeled ASL signs for plant and animal species and acted as epistemological mentors for the non-disabled deaf youth. This project was a better version of ecological deaf pedagogy.

3.4.2. Juxtaposing Narratives

In both examples, there are things I (Skyer) would do differently. First, I regret not conceptualizing a better ecology project. I recall thinking its multimodality was pedagogically transformative. Instead, it was a source of environmental pollution (disposed acrylic fragments, nylon, and Styrofoam). Second, I wish I’d involved Deaf members of the local Indigenous communities, including the nearby Seneca Nation of Indians (Haudenosaunee/Iroquois Federation) who are active educational partners in the Western New York region who recently inaugurated the Seneca Early Learning Childhood Centers (JCJ Architecture, 2025).

3.4.3. McKay-Cody

McKay-Cody is of Cherokee, Shawnee, Powhatan, and Montauk descent. She earned her doctorate at the University of Oklahoma researching North American Indian Sign Languages (NAISL). She is a learner of 15 NAISLs. She is a tribal elder, in addition to her work as a university-based researcher of Indigenous Deaf Culture. Her research preserves tribal sign languages and expands scientific understanding of them alongside multimodal forms of Native ceremony, culture, and record-keeping. Uniquely, McKay-Cody analyzes petroglyphs and rock paintings that comprise key aspects of Deaf Indigenous ways of understanding science and natural history. These artforms are multimodal ecological artifacts, both scientific and historical texts. In these first-person vignettes, McKay-Cody illustrates experiences being a deaf scientist and educator with Indigenous knowledge.

Vignette One

As a young person, I (McKay-Cody) lacked exposure to Indigenous Deaf pedagogy. What I learned about Indigeneity was inaccurate, including stereotypical information or “inaccurate universalization of the lives and experiences of Indigenous Deaf people” (McKay-Cody, 2019, p. 59). After graduating college, I moved toward tribal knowledge. My journey took me to Santa Fe, New Mexico’s Museum of American Indian Arts, where I handled, cleaned, and analyzed Puebloan pottery and arrowheads (points) in the Laboratory of Anthropology, and assisted at a nearby archaeological dig. My doctoral research connected tribal sign languages and petroglyphs. Both are Indigenous forms of science. Rock/picture writing is a terrestrial and scientific art form, transcending language and culture, to include the Earth itself. Seldom are petroglyphs included in K-12 or university STEAM education, but I use this knowledge to inform my teaching, including pedagogies that demonstrate how Indigenous images and symbols are linked to ancestral knowledge. I also invite students to look at petroglyphs in the canyons and deserts. In my research and teaching, I analyze petroglyphs as symbolic storytelling, and portray tribal persons who created them are scientists, artists, and authors. In my dissertation, I explain that petroglyphs are a “bridge between archeology, art history, and sign language research” (McKay-Cody, 2019, p. 87). Through exposure to this type of knowledge, I learned by doing and came to know myself as Indigenous and Deaf.

Vignette Two

Indigenous Deaf Methodologies are central for my teaching and research (McKay-Cody, 2019). Currently, I’m working on two projects that align with the DICE model. Both center Indigenous Deaf Elders, who model language and teaching. The first is a video dictionary of tribal sign languages, which moves from preservation to language revitalization. The video dictionary, when complete, shall be an excellent educational tool. Second, I’m developing a curriculum called Deaf Red Pedagogy inspired by Grande (2015). The work is currently a “pilot study,” but it will eventually be used in deaf residential schools nationwide. Deaf Red Pedagogy is an immersive, visual, and multimodal teaching framework, suited to the learning characteristics of deaf students. Few Indigenous Deaf people are familiar with Indigenous culture, history, and sign languages. Deaf Red Pedagogy therefore explores place-based, culturally responsive teaching strategies, alongside knowledge constructed from local tribal signs. Deaf Red Pedagogy includes hands-on experience with raw materials found on Mother’s Earth. It also draws on science and literacy teaching, which evokes traditional storytelling to spiritually connect people to the world below, around, and above us.

3.4.4. Juxtaposing Narratives

In both narratives, I (McKay-Cody) illustrate how DICE could be developed to support ongoing research. Deaf Red Pedagogy is tailored to the needs of deaf students because nothing of its kind yet existed. Unlike oral-focused Red Pedagogy (Grande, 2015), Deaf Red Pedagogy employs signed, visual, and tactile teaching methods and uses a slower pace to encourage deeper engagement with tribal information and support time for conceptualization for Indigenous Deaf students who have often experienced language deprivation as well as cultural deprivation. Like DICE, Deaf Red Pedagogy can use direct instructional methods or be presented with certified NAISL interpreters who understand Indigenous terminology and Native pedagogies.

4. Findings from the Literature Synthesis

This section responds to research question one. We situate DICE as a potentially transformative conceptual framework to reinvigorate communities and ecologies at risk from runnamok capitalism, aftereffects of colonialism, and the STEM ideologies fueling their rapacious engines. Together, DICE may enhance deaf and Indigenous Deaf students’ learning, creativity, and ecological awareness, meanwhile advancing humanity’s macrostructural coherence. DICE is not an end, but a means to generate new research.

Four major dialectics resulted from our literature synthesis. The first defines STEM ideologies and describes their legacy of harm. The second explores Indigenous sign languages and colonialism, introducing the dilemma of epistemic resource extraction. The third examines how DICE is a situated approach to STEAM education built with Indigenous Deaf artforms and deaf and Indigenous Deaf educational languacultures to align pedagogies and curricula. The fourth posits the triadic nucleus for our conceptual framework: collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis.

4.1. What Are STEM Ideologies?

Our planet is at the brink of calamitous ruin (Morton, 2016; Orf, 2024; Orr et al., 2024). This epochal crisis has several names. All variations of a central theme. The Holocene describes Earth as “characterized by humanity’s dominance over the planet’s ecological systems and biogeochemical cycles” (Agenbroad & Fairbridge, 2024, n.p.). The Anthropocene “binds together human history and geological time” (Morton, 2016, p. 8). Additionally, the Capitalocene foregrounds “rampant capitalism’s role in global ecological destruction” (Bertling, 2023, p. 151).

Rather than debate nomenclature, we propose that these linked crises are caused and exacerbated by insufficient ecological ethics that are then weaponized in STEM education, or when ecologically agnostic STEM knowledge is used by governments and industries (de Alba et al., 2000; Bertling, 2023). STEM ideologies are interstitial: Hard to pinpoint, elusive yet omnipresent. STEM ideologies are integral to doing Western science. There is no shortage of governments seeking total domination of the Earth’s vast more-than-human entities and human inhabitants, partly by weaponizing industrial sciences (Marx & Engels, 1848; Zinn, 1980/2003). Liberal, conservative, communist, and fascist systems all welcome and embrace the opacity of STEM ideologies—indeed, government all but requires this occultation (Uekötter, 2007).

STEM industries are implicated in ecocide and genocide. They imperil the Earth’s interdependent systems with special risk for vulnerable humans and more-than-human entities (Nicol et al., 2023a, 2023b; Glanfield et al., 2020; Thom, 2019). STEM ideologies are not convenient strawmen. They are propaganda for industrial forms of agriculture, forestry, petroleum engineering, and biotechnology (Agenbroad & Fairbridge, 2024; Leopold, 1949; Morton, 2016; Thom, 2019). STEM ideologies prioritize human hierarchies: capital over nature, science above ecology (Bookchin, 1982/2005). STEM ideologies prioritize capitalist and colonialist economics antithetical to Indigenous lifeways (Le Guin, 2015; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022).

How Do STEM Ideologies Impact Humans?

STEM ideologies are abstractions, operationalized by concrete actors in reification, where theory transmogrifies into lived reality. While these constructs are not inevitable, STEM ideologies consistently produce widespread disablement and harm vulnerable people (Bookchin, 1982/2005; D. M. Bowers et al., 2024; Coulthard, 2013; Puar, 2013). We focus on two areas of praxis. First, we describe examples of powerful human agents who wield and weaponize STEM ideologies against the Earth, against deaf and disabled peoples, and against Indigenous peoples (singly or in combination). Examples include:

- Capitalist politicians ostensibly operating in the public sector imperil life at global scales. In the US-context, George W. Bush (2001–2009) unilaterally withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol. Donald J. Trump (2017–2021, 2025–present) has withdrawn the US from the Paris Agreement. Twice.

- Chairmen, board members, and shareholders in the industrial private sector enable extractive capitalism. Multinational pharmaceutical-biogeochemical conglomerates like “Big Pharma” and “Big Oil” profit by extracting resources, which decimate local ecologies and communities (Lal et al., 2024; Puar, 2013).

- University deans and program heads prop up militarism. Of these, the most egregious is the weaponization of physics departments during WWII (McCarthy, 2022). Less overtly, higher education personnel include members of curriculum committees who authorize syllabi centering Western canons of science and technology, and feature meta/narratives often written by affluent White, able-bodied, men of European descent (Cajete, 2000; Solomon & Aikenhead, 1994).

- Across the Middle East, Canada, and United States, tragedies occur when oil conglomerates ravage Indigenous lands (Morton, 2016). From the Albertan tar sands where oil workers bodily assault First Nation peoples to the militaristic responses against Native water protectors at Standing Rock, these are incursions into Inuit and Chipewyan territory (Alberta) and Dakota and Lakota lands (Standing Rock) (Morin, 2023). These are colonialist exchanges: Soil for oil. Water for talings. Territory for (broken) treaties.

The second area of praxis for STEM ideologies are people and environments downstream from decision-makers in industry and government. Examples include:

- The taxonomic neutrality of prose written by a museum worker upon a catalog-card, whose words describe the last known specimen of a now-extinct species, expressly collected as such. The word “Endling” describes this nihilism (Nijhuis, 2017).

- A university lecturer of anthropology not affiliated with any tribe hoists stolen human remains from Indigenous tribes in Southern California. These are the mortal remains of people whose ancestral bodies have been venerated for millennia as contemporary spiritual leaders and cosmological teachers (Hudetz & Brewer, 2023).

- Infrastructure employees of a “green tech” company direct the extraction of raw lithium, cobalt, and cadmium by Black Africans working under slavery (United States Department of State, 2022).

- A deaf environmental science student traded in her field boots and Estwing chisel to gain lucrative employment as a surveyor for a transnational oil conglomerate (American Chemical Society, 2025).

- A Chignik fisherman lives near a newly erected hydro-electric dam, which bisects traditional spawning pathways of indigenous salmon. At a local council meeting, the fisherman listens to the architect explaining that the project will create green jobs and clean energy for electric cars (Ingram, 2024).

STEM ideologies harm the Earth by ideological framing of actual events (Cajete, 2000; de Alba et al., 2000; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). STEM ideologies are occult unless actively interrogated. Thus, we aim to obviate their impact. As the old protest saying goes: The earth is not dying, it is being killed. Those doing the killing have names and addresses.

4.2. Indigenous and Exogenous Sign Languages

The following analysis under the DICE rubric underscores the transformative potential for deaf and Indigenous Deaf languacultures, as theorized through a lens about biocultural deaf gains. Here, we examine some uncomfortable sociohistorical tensions that exist between Indigenous sign languacultures and the legacy of colonialism. By juxtaposing contemporary challenges and historical context, languacultural revitalization may occur for all sign language communities through expanded educational access and increasing the focus on sustainable values about environment/ecology and equity for marginalized groups across ontological divides (e.g., non/Indigenous, dis/ability, gender, socioeconomic class, etc.). While we focus on Indigenous sign languages in North America, it’s important to recognize that Indigenous sign languacultures exist worldwide. While each history is distinct, similar dilemmas and opportunities arise across contexts. Table 1 is included below to support our readers’ analysis of two key terms, indigenous and endogenous sign languages. Both language forms are creative but rule bound and structured in terms of morphology, phonology, syntax, pragmatics, and grammar.

Table 1.

Indigenous and exogenous sign languages.

4.2.1. Indigenous Sign Languages

Indigenous sign languages are conventionalized, place-based systems of information exchange among Indigenous people (deaf and not) containing recognizable “signs” made of hand shapes, movements, and other externally embodied features alongside syntactic and lexical complexity, and grammatical regularity (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; Mitchell, 2024; McKay-Cody, 2019). Morphemes include gestures, facial expressions, and other meaningful units with externally embodied features (Sherley-Appel & Bonvillian, 2014). Sometimes called “hand sign,” “hand talk,” or “sign talking” (Tomkins, 1969), Indigenous tribes developed sign languages for three purposes:

- (1)

- Intra-tribal exchanges among Natives of one tribe;

- (2)

- Inter-tribal exchanges among Natives from two or more tribes;

- (3)

- Cross-cultural exchanges between tribal persons and settlers.

North American Indian Sign Languages (NAISL) were developed by historical Indigenous peoples and continue to be used by contemporary Indigenous peoples across North America. Examples include Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), Great Basin Indian Sign Language, Southwest Indian Sign Language, and the respective sign languages of the Kiowa, Northern Cheyenne, and Crow tribes (Mitchell, 2024; McKay-Cody, 2019).

NAISLs are educationally beneficial for Indigenous Deaf persons who use the languages to exchange tribal knowledge in the community and to subversively sign in residential Indian schools and deaf residential schools (Adams & Gilroy, 2024). While NAISLs were initially developed exclusively to benefit Indigenous people (e.g., inter- and intra-tribal, communications), colonialism introduced the need for cross-cultural exchanges. Famous documentary evidence comes from US Army General H. L. Scott (1930), who filmed PISL at the Indian Sign Language Council. The US Military had the early insight that Native sign languages were strategically valuable—without surprise, this knowledge was weaponized in genocidal “Indian Wars.”

4.2.2. Endogenous Sign Languages and Colonialism

Endogenous sign languages are modern sign languages of colonial nations sharing one national identity. In some cases, as with ASL, an exogenous sign language is international, linking communities (e.g., across the US and Canada) (Skyer, 2021). Endogenous sign languages are used in majority sign languacultures. Familiar examples include ASL and French Sign Language (FSL) in the Western traditions, and LIBRAS (Brazilian sign language) and Lengua de Señas Mexicana (LSM), in Central/South America (Fox Tree, 2020). Of several sign languages circulating in the United States, ASL is by far the most dominant (National Geographic Society, 2025). The ontogenesis of ASL provides a canonical antecedent for DICE researchers to analyze. ASL is an autochthonic language bearing all the formal trappings of linguistic complexity (Calton, 2014; Leigh et al., 2023). Researchers widely recognize that ASL “borrowed” signs from European sign languages, like FSL (Cagle, 2010); however, knowledge that ASL incorporated signs from North American Indian Sign Languages is less widespread (McKay-Cody, 2024).

Globally influential exogenous sign languages can displace local Indigenous ones through settler colonialism. We do not use “colonialism” metaphorically (R. Moges-Riedel et al., 2020; Tuck & Yang, 2012). We refer to harmful material effects on Indigenous Deaf peoples (Bone et al., 2021; Edward, 2021; Fox Tree, 2020). Colonial relationships imprint Indigenous Deaf languacultures through “glottophagy,” the process by which one language “eats” another. Curiously, the process is also called “language cannibalism” (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014), a term with racist and xenophobic origins. In Guatemala, Fox Tree (2020), shows how the European-based sign language (Lengsua) exhibits “linguistic colonialism” against the Indigenous Meemul Ch’aab’al (p. 43). Elsewhere, Indigenous Hawaiian Sign Language, first documented in 1821, was nearly eradicated by ASL within a century (Perlin, 2016). Musengi’s (2023) work on pan-African Indigeneity calls for postcolonial frameworks prioritizing indigenous sign languages in deaf education. Similarly, Asonya (2019) discusses efforts to decolonize Nigerian Sign Language, first documented in the 17th century, and is now at risk from extinction.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) estimates that 80% of global deaf populations live in below-average or low-income countries. In these locations, two adjacent forms of colonialism exist: religious missionary activities and sign language tourism. Missionaries export exogenous sign languages to nations under ethno-religious colonialism (Musengi, 2023; Oates, 2022). Differently, deaf sign language tourism (Jensen et al., 2023) involves affluent Westerners observing Indigenous Deaf people in impoverished nations like India, Nepal, Indonesia, or across the Caribbean region. Religious conversion and quasi-ethnographic sightseeing tours may appear benign or altruistic, but risk fostering cultural dependence and imperialism, where glottophagy occurs and local deaf languacultures slowly acclimate to exogenous deaf languacultures to support capitalist trade.

4.3. STEAM and DICE—Multimodal, Multilingual Pedagogies and Curriculum

4.3.1. Indigenous Deaf Axiologies and Artforms

STEAM studies in deaf education consistently show that multimodal-languacultural congruence generates effective teaching and learning (Adler, 2025; Henderson et al., 2023; Pagliaro & Kurz, 2021). Within this space, DICE could centralize Indigenous axiological domains, including ecological aesthetics and biosocial ethics emphasizing Earth’s macrostructural sustenance. For instance, Elmer Ghostkeeper (Métis) understanding of what Indigenous-ecological mathematics might mean living with—not upon—the Earth (Glanfield et al., 2020; Nicol et al., 2023a, 2023b). DICE underscores the need for greater prominence and integration of the Arts. As Bertling (2023) argues, an “arts-infused revisioning of the transdisciplinary STEM education model [via] creative problem-solving [can address] environmental concerns [and] climate change” (pp. 33–34).

Indigenous Deaf artists are valued epistemologists whose artworks can inspire DICE pedagogy and curricula. Prominent artist Nancy Rourke is deaf and Indigenous (Kumeyaay). Her oeuvre explores anti-colonialism, anti-audism, and the preservation of sacred lands. John Clarke is a Blackfeet Deaf carver who uses raw natural materials to depict wildlife. James Wooden Legs (Northern Cheyenne), uses animal bones, antlers, shells to build tribal regalia and represent traditional wisdom. Dennis Long (Navajo, Diné) is a weaver who uses local sheep wool and natural dyes. Ojibwe artist Richard Clark Eckert carves turtles and river otters in veined green soapstone. Similarly, two collections featuring Indigenous Deaf artists have been compiled. One is by Christie and Durr (2024), who showcase symbolic foci about Earth, roots, and water. Surdists United (2021) curate Indigenous Deaf artforms that explore nature, conservation, and sustainability. These artforms, rich with symbolic motifs, could creatively enhance STEM deaf education by fostering biosocial inquiry about ecological sustainability.

4.3.2. Case Analysis of Gabriel Arellano

Gabriel Arellano (2019, 2020) teaches in Indigenous Deaf languacultures in the Southwest US. Arellano is deaf and identifies with Mayan and Aztecan tribes (The Social Scientist, 2022; Sustainable Austin Blog, 2024). He works in residential deaf schools in New Mexico and Texas. He leverages STEMSigns, curricula and pedagogies of his own invention. Arellano’s work evidences multimodal objects like robots alongside “Native Sign Languages [and] multilingual and multicultural media” (2024, n.p.). Natural materials are prominent in his ecological pedagogy, which unfolds in the forested watercourses of the Blunn Creek basin in Texas.

In his version of STEM education, traditional native beadwork and animal remains connect Indigenous Deaf people with conservation. Reinforcing our DICE model, Arellano (2024) is critical of macrostructural inequalities and sources of harm that befall Indigenous Deaf people; he instructs teachers and students this way: “Do not stop acting until every being (plants, animals, and all [else]) is liberated from oppression” (n.p.).

4.4. The Nucleus of DICE

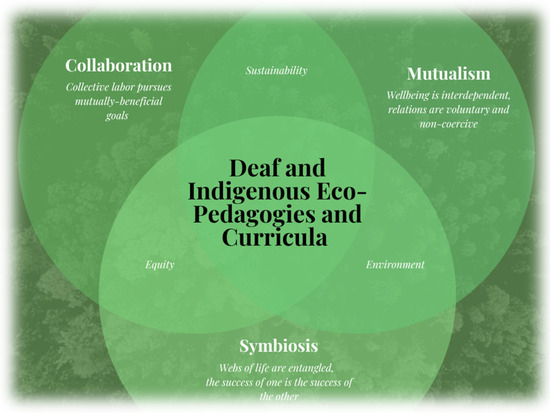

Collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis (definitions follow) are the triadic nucleus for DICE, which center the arts to support sustainability, equity, and environmental preservation. Collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis emphasize earnest epistemological regeneration, drawing on a logic that co-presents Indigeneity and deaf onto-epistemologies as equipotential with reciprocal umwelten, latent with educational forms of deaf gain (Paris & Alim, 2014; Skyer & Cochell, 2020). The nucleus aims to fortify imperiled knowledges, sustain threatened Indigenous Deaf ways of being, and develop philosophical, scientific and educational methodologies to benefit all human and more-than-human children of Earth who root in its soils, emanate from its air, and flow through its waters (See Figure 1, below).

Figure 1.

The Nucleus of DICE.

Collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis are likewise captured in the current ASL sign for INDIGENOUS (See: Figure 2), as modeled by Marc Morales (Aztec), who is Indigenous and Deaf. The sign suggests an emergence from the Earth and a concurrent embeddedness with the Earth. The sign represents that Indigenous Deaf lifeways are reciprocal with Earth, where the Earth sustains the people and the people sustain the Earth. Importantly, one author of this article (Melanie McKay-Cody) led this sign’s development. McKay-Cody (2019) collaborated with two American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters, Amy Foster and Heidi Storme, to create and refine the sign, which has since seen widespread uptake in the US and Canada. This process highlights the interconnectedness of human knowledges, languacultures, and ecology, all central to DICE’s mission.

Figure 2.

“Indigenous” in ASL. Image Sources (00:16–00:17): “Explanation of Native American Sign.” (Texas School for the Deaf, 2021), Statewide Outreach Center. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNVnjsu1BpE (accessed on 20 August 2025).

To explore our nucleus, we define terms and situate findings from our literature synthesis.

4.5. Collaboration

To collaborate is to labor collectively in pursuit of reciprocal, mutually beneficial goals across human knowledges and more-than-human entities. Indigenous Deaf epistemologists posit that collaboration exists between humans and more-than-human lifeforms; that scientific knowledge emanates from fauna, waterways, trees, soil, and seeds. “Native American farmers place a spiritual value on the ways nature intersects with human labor.” (Semali & Maretzki, 2004, p. 103). Edward (2021) writes, “Indigenous Deaf communities in Africa represent a diverse meeting of individuals who come together” to fight eugenics and poverty. Indigenous Animal Medicine is another biosocial collaboration, where people divine wisdom from insects, birds, and mammals (Erdoes & Ortiz, 1984; Sams & Carson, 1988).

While STEM ideologies denigrate collaborative practices under a Western scientific gaze (Abram, 1997; Cajete, 2000), deaf students, Indigenous people, and STEM educators in agricultural sciences, geosciences, chemistry, and biology could benefit enormously from human/nonhuman labor collaborations. Deaf students thrive with collaborative learning (Skyer, 2021). Raike et al. (2014) observe that “iterative collaboration with Deaf students” (p. 415) reveals uniquely creative and aesthetic perceptions of educational and natural lifeworlds. Deaf umwelten and Indigenous Deaf umwelten benefit from collaborative sensory perception. Heightened sensory connections with the natural world are biocultural deaf gains, which could be explored with mindfulness practices, such as forest bathing (Haupt, 2021) or ecological walking (Bertling, 2023).

To these observations, we add new queries: What teaching and learning methods in STEAM education can deaf and Indigenous people explore to collaborate in defense of the Earth? How can educators authentically integrate the contributions of Indigenous Deaf people working to transform STEAM? What signs, artforms, and languacultures could transform STEAM education through the DICE conceptual framework?

4.6. Mutualism

Mutualism is the doctrine that biosocial wellbeing is interdependent, voluntary, and non-coercive (Bookchin, 1982/2005; Jones et al., 2021). Deaf, disabled, and Indigenous people have applied mutualism to combat neoliberalism, neofascism, and capitalism through education (Ben-Moshie et al., 2009; Puar, 2013; Skyer et al., 2023d). Deaf education practices in STEAM informed by Indigenous Deaf educators can embody mutualism and foster interdependent ecologies or heterarchies rather than hierarchies (Skyer, 2021). Likewise, McKay-Cody’s (2019) research on nature-based art/science modalities exhibits a mutualist languaculture—knowing with the Earth.

Turtle Island Hand Talk (TIHT) is an organization led by Indigenous Deaf women that exemplifies mutualism (McKay-Cody, 2022). Founder Kristina Belleau (Ojibwa) organized civil rights reforms in Canada. Member Hallie Zimmerman (Winnebago, Omaha) advocates for Indigenous Deaf education in the US via a mutualist framework. Other TIHT members are hearing: Dr. Waynette Reynolds (Cherokee, CODA), Paola Morales del Castillo (Matlatzinca, Nicaro), Tia Ivanko (Nipmuc), Carol Smith (Cherokee), and Raylynn Skeets (Diné). These women provide mutual aid through Indigenous Sign Language interpretation at Native American healing ceremonies, such as the We Are Still Here arts exhibition. New Interpreter Training Programs (ITPs) have been encouraged to produce multilingual interpretation with Indigenous Deaf people, including intertribal, intratribal, and cross-cultural translation (Johnson et al., 2024). DICE is a model for community members, ITPs, and STEAM educators who wish to integrate ecological values alongside mutualist Indigenous Deaf languacultures.

To these observations, we add new queries: How can deaf people mutually learn with Indigenous people while resisting colonial and capitalist STEM ideologies? How can Indigenous groups benefit from mutualist collaborations with deaf umwelten, as through STEAM pedagogies using visual, tactile, and embodied modalities? How might mutualism be fostered between schools and communities where Indigenous Deaf people live and work?

4.7. Symbiosis

Symbiosis is together-living. Symbiosis is life itself: Consider mitochondria. Symbiosis demonstrates how systems are interpenetrating; that webs of life are entangled; that the success of one depends on successes of others (Maran et al., 2012). Symbiosis welcomes the “embeddedness of the human within a broader system” (Aronowsky, 2021, p. 79). Bagga-Gupta (2004) writes that deaf languacultures rely on “close symbiosis” with other lifeways (p. 186). Symbiotic logic extends to Indigenous Deaf communities in knowledge preservation, where lifeworlds are connected through families, tribes, education, governance, land, animals, and reciprocal relations with Earth (Snoddon et al., 2024).

Symbiotic interactions among Indigenous, disabled, and more-than-human entities create socio-ecological harmony (Bookchin, 1982/2005). Morris (2017) writes that this symbiosis is a relational onto-epistemology based on agency and interdependence: “Biospherical egalitarianism [emphasizes] diversity and symbiosis, a fight against class exploitation [is also] against pollution and resource depletion.” Reflecting on his ethnographies with deaf tribal Laotians and Cambodians, Wrigley (1996) writes, “deafness is part of the biopolitics of nature” (p. 220). Through symbiosis, mutualistic nodes connect humans—deaf and hearing, Indigenous and not—with animals, minerals, plants, and fungi, creating elegant, macrostructural coherence.

Alongside other ideas, we wonder, can STEAM and DICE educational constructs prevent or reverse ecological destabilization? Can Indigenous Deaf ontologies contribute to sharing epistemologies and languacultures that uphold life’s delicate symbiotic complexity and preserve the diversity of human cultural milieux?

5. Discussion

To examine question two, we open with a reinterpretation of STEAM. Then, we explore a vision for implementing DICE in schools and universities. Next, we interpret tensions between the pedagogy of poverty and the pedagogy of plenty (Cole, 2008) in Indigenous Deaf education. Then, we analyze epistemic resource extraction and suggest solutions for replenishment. Lastly, we describe the underdeveloped research base and invite scholars to enlarge knowledge about DICE.

5.1. STEAM Through DICE

We propose a novel interpretation of STEAM through the DICE framework:

Sovereignty—Deaf peoples and Indigenous peoples each operate with a desire for internal autonomy; and yet, both desire opportunities for cohesion and co-habitation within and across cultures and subcultures working at common purpose.

Territory—Deaf people are a geographically dispersed languaculture. Indigenous people have had their territories stolen through imperialism and colonialism. Territory is contested and necessary for both groups to survive and thrive.

Environment—Deaf people and Indigenous people each experience the natural world singularly. These umwelten may benefit from further “cross-pollination,” perhaps epitomized by how Indigenous Deaf scientists work, learn, and share resources and knowledge through petroglyphs—science inscribed on Earth.

Axiology—Deaf and Indigenous people each have valuational worldviews that challenge and de-center hegemonic precepts of authority, often emerging from Western, White, masculine conceptualizations of scientific certainty. Deepening the entanglement of Indigenous and deaf lifeways is justified.

Memory—In both deaf and Indigenous communities, preservation of history through realia and narratives are critical portals into values, knowledge, and being. For Indigenous people: Wampum belts and Whale’s extended memory. For deaf people: George Veditz’s historical film on sign language preservation and contemporary vloggers fighting audism on TikTok.

5.2. Implementing DICE

DICE deepens existing connections between arts, languacultures, biocultures, and STEAM education across deaf, disabled, Indigenous, and gender-minority corporealities. Authentic implementation requires collaboration, mutualism, and symbiosis with local Indigenous Deaf experts. DICE implementation could honor cosmological-ecological formations about science (Cajete, 2000) by exploring Arellano’s (2019) STEMSigns. DICE in STEAM could involve deaf people learning through eco-conscious poetry (Sanchez, 2020) or Native dance ceremonies. Deaf youngsters might learn fractions, ratios, or principles of complementarity through indigenous food culture, such as The Three Sisters. DICE could transform STEAM education via Indigenous and Deaf perspectives, but the work cannot be adequately done without authentic cooperation and epistemic humility.

Second, implementing DICE in STEAM could emphasize multilingual, multimodal arts as pedagogy and curriculum (Henderson et al., 2023; Kurz et al., 2021; Pagliaro & Kurz, 2021). To address language deprivation, Indigenous Deaf artists could enrich early childhood curricula with iconographic materials about ecosystems (Elevenbee Co, 2025). Deaf high school students could learn mathematics for social justice (Gutiérrez, 2022; Gutstein, 2003) by collaborating with Indigenous signing elders and deaf studies faculty (McKay-Cody, 2019). Conferences could be themed around revitalizing Indigenous Deaf languacultures and artforms to sustain and expand biocultural diversity, which could spur collaborations between deaf environmental scientists, sign linguists, and Indigenous Deaf elders to build new sign lexicons for environmental problems and solutions.

We are limited only by our imaginations.

5.3. Pedagogies of Poverty and Plenty

Economic poverty is a structural outcome of capitalism. Poverty causes brain damage (Hair et al., 2015). The “pedagogy of poverty” describes harmful or inadequate education systems (Cole, 2008). Language deprivation syndrome is widespread in deaf communities. Language deprivation inhibits brain growth and causes neurobiological disorder (Gulati, 2019). Sociocultural and economic destitution is widespread among Indigenous Deaf people. In the United States and Canada, a brutal history of Residential Indian Schools have exploited exogenous sign languages and colonial rule to harm generations of Indigenous Deaf people through glottophagy and educational coercion (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014).

Poverty, pedagogies of poverty, and language deprivation are all widespread sources of harm that devastate Indigenous Deaf people (McKay-Cody, 2024; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014; Snoddon et al., 2024; Weber, 2020a). All must be expunged.

5.3.1. Pedagogy of Poverty

Implementing DICE could include a sustained focus on eradicating structural poverty and ending the pedagogy of poverty in deaf education. Destructive negative values about Deaf and Indigenous languacultures stultify educational potential. When mother tongues and other tongues are excluded, Indigenous Deaf languacultural exclusion “perpetuates poverty,” diminishes “linguistic and cultural competence,” and “causes serious mental (and even physical) harms” (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014, pp. 496–497).

McKay-Cody (2024) explains the mechanisms by which these poverties harm:

Within the Indigenous Deaf community, the reasons for struggles are widely known. […] This negative view primarily stems from the influence of past research, which heavily relied on [inaccurate] rehabilitation studies. […] In scholarly [literature,] Non-native scholars across a wide range of disciplines have exploited [Indigenous Deaf people] and published research rife with ethical violations […] causing profound communal trauma [and] educational trauma. [As a direct result,] many Indigenous Deaf people do not have good literacy and their understanding [of] dense academic [subjects] and legal forms has presented challenges.(p. 90)

5.3.2. Pedagogy of Plenty

Poverty pervades Indigenous deaf education. It and could be replaced with a pedagogy of plenty (Cole, 2008). A model to explore is the mutualist Indigenous practice of potlatch. Potlatch is an Indigenous ceremony in which possessions are given away by those with prestige in a display of mutual support for those in need. Potlatch is a system of governance, a system of resistance, and a survival strategy (Wilner, 2013). Potlatch fosters healing. Celebrated under Turkey’s Animal Medicine, potlatch inspires resilient mutual aid among Indigenous groups. The method was so effective, US (Sams & Carson, 1988, pp. 313–317) and Canadian governments (Wilner, 2013, p. 89), worked to outlaw the practice among tribes.

How might potlatch be enacted under DICE? McKay-Cody (2019) coined two terms, Childhood Communicative Kinship (CCK) and Ethnic Communicative Kinship (ECK). Both could revitalize impoverished languacultures. CCK foregrounds constructed kinships (e.g., “found families”) among deaf people built through residential schooling. ECK deepens kinship in shared ethno-racial groups and enables Indigenous Deaf people to absorb tribal values about sustainability and ecology. DICE could support researchers conducting formal analyses of inadequate “school curricula” (Tuhiwai Smith, 2022, p. 8) and support self-determination in Indigenous Deaf education through authentic decolonization.

The DICE framework seeks to invert structural and pedagogical destitution through intrinsic and extrinsic biocultural deaf gains in STEAM education. Uplifting Indigenous Deaf gains (Adams & Gilroy, 2024) advances equity while promoting global ecological flourishing through mutualistic symbiosis (Maran et al., 2012). Strengths emanating from Indigenous Deaf umwelten can unsettle (Tuck & Yang, 2012) stuck places and challenge deficit thinking in deaf education and Indigenous Deaf education. Research outside deaf education can guide this work. Gutiérrez’s (2022) ethical-spiritual turn in mathematics education and Nicol and colleagues (Nicol et al., 2023a, 2023b) place-based STEM education integrate onto-epistemology and axiology by emphasizing sacred practices of care for the self and others alongside care for the Earth.

5.4. Epistemic Resource Extraction and Replenishment

Separately and together, Indigenous and deaf communities confront scientific exploitation (McKay-Cody, 2024; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). Indigenous people are wary of scientific research because knowledge manipulated with hostile intent benefits Western colonizers and harms Indigenous people (Cajete, 2000; Sams, 1990; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022; Tuck & Yang, 2012), as when pharmaceutical companies extract traditional Indigenous wisdom and appropriate resources (Lal et al., 2024). In deaf education, exploitation includes knowledge about sign languages benefitting hearing people without coequal exchanges for deaf people (Skyer et al., 2023d; Snoddon, 2014). Biomedical industries exploit hearing parents’ lack of knowledge to propagate clinical ideologies (Mauldin, 2016; Tabery, 2014). Subtractive bilingualism harms both Indigenous and deaf people. After cognition and language acquisition are primed, sign languages are tossed like detritus (Garcia, 2009; Skutnabb-Kangas, 2014).

While exogenous sign languages are materially beneficial to deaf people and are increasingly global languages, they should not be used to the exclusion of Indigenous languacultures, in or beyond STEAM. Indigenous Deaf people have a right to be educated and socialized in Native sign languages and in exogenous languages that are strategically important. New forms of mutual aid, community aid, and power-sharing are necessary. A specific dilemma about epistemic replenishment emerges for Indigenous Deaf people in the US. During the ontogenesis of ASL, non-Indigenous deaf Americans extracted epistemic benefits from signing Indigenous people. This debt has not been repaid. Doing so would be healing. Potlatch could be a model. Land acknowledgements are useful, but Land Back is necessary ontological replenishment. We do not need mere words about decolonizing syllabi; our communities require authentic Truth and Reconciliation.

5.5. Wrangling the Limited Literature

Constructing DICE showed why our synthesis was necessary. Our literature review encompassed theoretical and empirical studies, gray literature, and news media connecting ecology, STE(A)M education, and Indigenous Deaf languacultures. We found no journal articles that thoroughly integrated all variables. Despite extensive searches, we found persistent gaps: deaf education STEM resources had ecological themes but lacked Indigenous and arts perspectives (Communication Service for the Deaf, 2020a, 2020b). Indigenous research lacked pedagogical and curricular relevance for deaf education (Grande, 2015). A lack of Indigenous Deaf research from the Global South was noted. Notable works illustrated Indigenous Deaf educational languacultures, but not STEAM education (Konrad, 2024; Ward, 2024). STEM education often lacks deep engagement with ecological ethics, sidesteps disability (Coulthard, 2013; Bertling, 2023), and shows superficial ecology or anthropocentrism, which “undermine[s] the foundations of critical environmental education” (de Alba et al., 2000, p. 55).

Whether gaps were intentional or accidental, they perpetuate marginalization and harm people in deaf and Indigenous Deaf communities (McKay-Cody, 2024). Fragmented research highlights intersectional oppression, such as convergences of racism with ableism, xenophobia and audism, sexism or colonialism; all of which constrain STE(A)M deaf education and research (Adler, 2025; Bone et al., 2021; Mangan, 2023; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). Constructing DICE is our first step. Future studies might examine DICE theoretically, practically, and empirically to evaluate its merits and demerits as a framework for research, pedagogy, and curriculum across global contexts, age groups, and scenarios. If DICE is to be effective, investigations should be conducted by people with relevant positionalities, including deafness and Indigeneity, among other onto-epistemologies of difference including people from Global South, who are women, members of 2SLGBTQIA communities, and disabled scholars (singly or in combination).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Core Arguments

DICE advances three core arguments. First, traditional STEM ideologies, pedagogies, and curricula are problematic. They overwhelmingly center on White, able-bodied, Western, colonial sciences (Erevelles, 2005; Tuhiwai Smith, 2022). They assume authoritative scientistic axiologies that overvalue homogeneous, reproducible, hierarchical knowledge (de Alba et al., 2000), and project an ethos of human control over the Earth (Haupt, 2021).

Second, traditional STEM ideologies, pedagogies, and curricula are hostile to deaf and Indigenous people. They disdain, exploit, or dismiss onto-epistemologies from Indigenous Deaf environmental educators, scientists, and artists (McKay-Cody, 2024; M. Moges-Riedel, 2021), such as intelligences emanating from ecological artists and scientists (Bertling, 2023; Mangan, 2023). They support intersectional oppression, minoritization, marginalization, colonization, or underrepresentation of STEM epistemologists who are women, disabled, queer, Brown, Black, Indigenous, or people of color (De Clerck, 2017; Gertz & Boudreault, 2016; Lang, 2016; R. Moges-Riedel et al., 2020).

Third, without transformation, collisions between STEM ideologies, pedagogies, and curricula with STEAM and DICE are aporetic (Weber, 2020b). Aesthetic revitalization uplifts deaf arts education (Schiff, 2010). As Weber (2020b) writes, culturally relevant deaf arts education may offer “a way out” (p. 171) of posthuman aporias. Centering Indigenous Deaf epistemologists (Adams & Gilroy, 2024; De Clerck, 2012) may disrupt impending ecocide and genocide. Through purposeful indigenization of deaf environmental arts with emic STEAM knowledges, DICE synthesizes critical deaf pedagogy, environmental education, and arts education (Bertling, 2023; Musengi, 2023; Skyer, 2023b). Centering the arts and Indigenous Deaf languacultures may enlarge biocultural deaf gains, with intrinsic and extrinsic beneficiaries (Bauman & Murray, 2014).

6.2. No End in Sight

We are suspicious of the received view of STEM as a value-neutral, self-evident good, conducted by culture-free, bias-free technicians agnostic about ecology and axiology (D. M. Bowers et al., 2024). We reject STEM ideologies that lurch unsustainably toward “progress.” We reject the self-congratulatory march of industry while microplastics contaminate and displace plants, animals, water, air, even our very neurons (Messier-Jones et al., 2024). We refuse that our bones feed the insatiable maw of capitalism. STEM ideologies capacitate teratogenic environmental destruction from which deaf, disabled, and Indigenous people are uniquely targeted. Ecocide is a hyperobject of such enormous scale that it escapes the boundaries of human cognition (Morton, 2016). Yet, in our search to understand the origins of ecocide, we encounter systems that desire ecocide, that profit from ecocide. As an example, Genesis gives us this cryptic impetus: “Subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and of the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” (King James Bible, 2024, 1:28).

Along with Lorrain et al. (2001), we ask: “Can we call this life?” Indigenous scientist Cajete (2000) explains, “Western society’s systems of science [project an] aura of invincibility and god-like qualities” (p. 54). This ideology can never be tempered, only abandoned. As Coulthard (2013) writes “For Indigenous nations to live, capitalism must die. And for capitalism to die, we must actively participate in the construction of Indigenous alternatives” (n.p.). Without equivocation, we stand in solidarity with the social ecologists: “Capitalism’s grow-or-die imperative stands radically at odds with ecology’s imperative of interdependence and limits. The two imperatives can no longer coexist […] nor can any society founded on the myth that they can be reconciled hope to survive” (Le Guin in Bookchin & Taylor, 2015, p. 7).

If climate justice is racial justice (Kendi, 2020), then ecological justice (C. A. Bowers, 2003) includes disability justice (Engelman et al., 2022; Puar, 2013), social justice for deaf people (Yancey, 2023), and Truth and Reconciliation (Tuhiwai Smith, 2022) for Indigenous Deaf people (Adams & Gilroy, 2024). In solidarity with uprising Indigenous voices, deaf hands can rise from the Earth to aid its defense. Through biosocial languacultures, mutualism illuminates a forward path for deaf and Indigenous people to collaborate against ecocide and genocide and toward deepening symbiosis with Earth’s human and more-than-human complexity. As DICE germinates and roots, deaf and Indigenous peoples may deepen the ongoing exploration of scientific and artistic languacultures, centered on the active valuation of symbiosis, mutualism, and collaboration, as these are the ascendant, surging offsprings of human ingenuity.

6.3. A Pedagogy of Transcendence

Pedagogy transcends thermodynamics. In teaching, energy is created. Multiplied. Teaching is a spiritual act, imbued with philosophy, the love of knowledge in all forms. The DICE framework constructs probable pathways toward collaborative, mutualistic, and symbiotic relationships between the Earth, its more-than-human denizens, and deaf and Indigenous lifeways.

To conclude, Deaf-Indigenous Curricula and Eco-pedagogies (DICE), collocate worldviews to engender a new sensus—a hybridized onto-epistemology replete with new (and lost) senses and new (and ancient) sensibilities. Indigenous Deaf umwelten encourage new (and ancient) explorations of art through STEAM deaf education research. We aim for new pedagogies, curricula, and politics, along with new artforms, languages, and modes of care for ourselves and the Earth that can stop genocide and reverse ecocide.

Radical mutualism is the path.Biocultures contra biocide.Ecology subverts ecocide.There is no alternative.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.E.S. Methodology: M.E.S. Investigation: M.M.-C. and M.E.S. Writing—original draft and preparation: M.E.S. Writing—review and editing: M.M.-C. and M.E.S. Visualization: M.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to Melissa Diane Skyer, a deaf environmental scientist and student of animal medicine. She is with the Dragonflies now.

Author’s Note

Valuable research assistance was provided to Michael by Leah Oakes, PhD student. Valuable spiritual guidance was provided to Michael by Judy Buckley.

References

- Abram, D. (1997). The spell of the sensuous. Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R., & Gilroy, H. (2024). The importance of Indigenous sign languages on the cultural empowerment of Deaf Indigenous people. In J. T. Ward (Ed.), Indigenous disability studies. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, H. J. (2025). Language complexities for deaf and hard of hearing individuals in their pursuit of a career in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and Medicine. Perspectives form an LSL/ASL user. Ear and Hearing, 46(4), 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, M. (1980). The professional stranger: An informal introduction to ethnography. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agenbroad, L. D., & Fairbridge, R. W. (2024, August 13). Holocene environment and biota. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/Holocene-Epoch (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- American Chemical Society. (2025). Geochemistry. Available online: https://www.acs.org/careers/chemical-sciences/fields/geochemistry.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Arellano, G. (2019, November 15). STEMSigns. Bulb. Available online: https://www.bulbapp.com/u/stems~2 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Arellano, G. (2020, September 1). STEM & sign language integration in K-12 education [Conference Session, Video]. National Deaf Education Conference 2020. Available online: https://deafeducation.us/stem-sign-language-integration-in-k-12-education-gabriel-arellano (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Arellano, G. (2024). Available online: https://www.stemsign.org/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Aronowsky, L. (2021). Biospheric politics. In C. A. Jones, N. Bell, & S. Nimrod (Eds.), Symbionts: Contemporary artists and the biosphere (pp. 79–86). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Asonya, E. (2019). Decolonizing African sign language system: The roadmap. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@easonye/decolonizing-african-sign-language-system-the-roadmap-d6193fe18923 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Bacca, P. I. (2019). Indigenizing international law and decolonizing the Anthropocene: Genocide by ecological means and indigenous nationhood in contemporary Colombia. Maguaré, 33(2), 139–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga-Gupta, S. (2004). Literacies and deaf education a theoretical analysis of the international and Swedish literature. The Swedish National Agency for School Improvement. [Google Scholar]