Looking for Answers: A Scoping Review of Academic Help-Seeking in Digital Higher Education Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- Q1. What is the nature of contemporary HE AHS literature containing a digital aspect?

- Q2. To what extent are these studies grounded in theory and how are these theoretical and conceptual frameworks described?

- Q3. Which sources (or resources) of help are identified across this literature?

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Help Seeking

2.2. Digital Technologies in Higher Education

2.3. Human-to-Human and Digital AHS?

2.4. Students’ Requirements for Help with Digital Technologies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Pilot and Search Terms

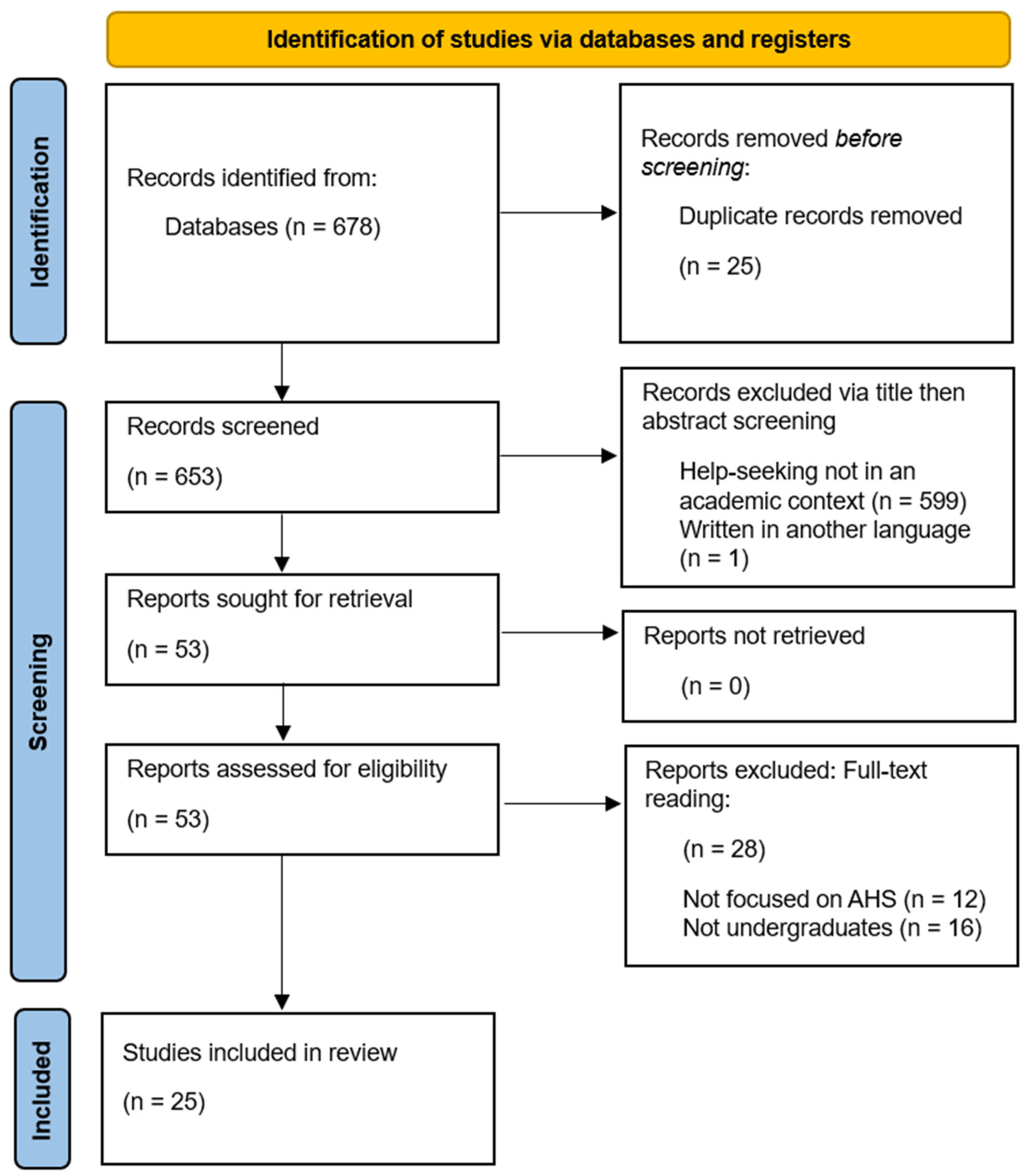

3.2. Study Screening and Selection

3.3. Information Extraction

4. Results

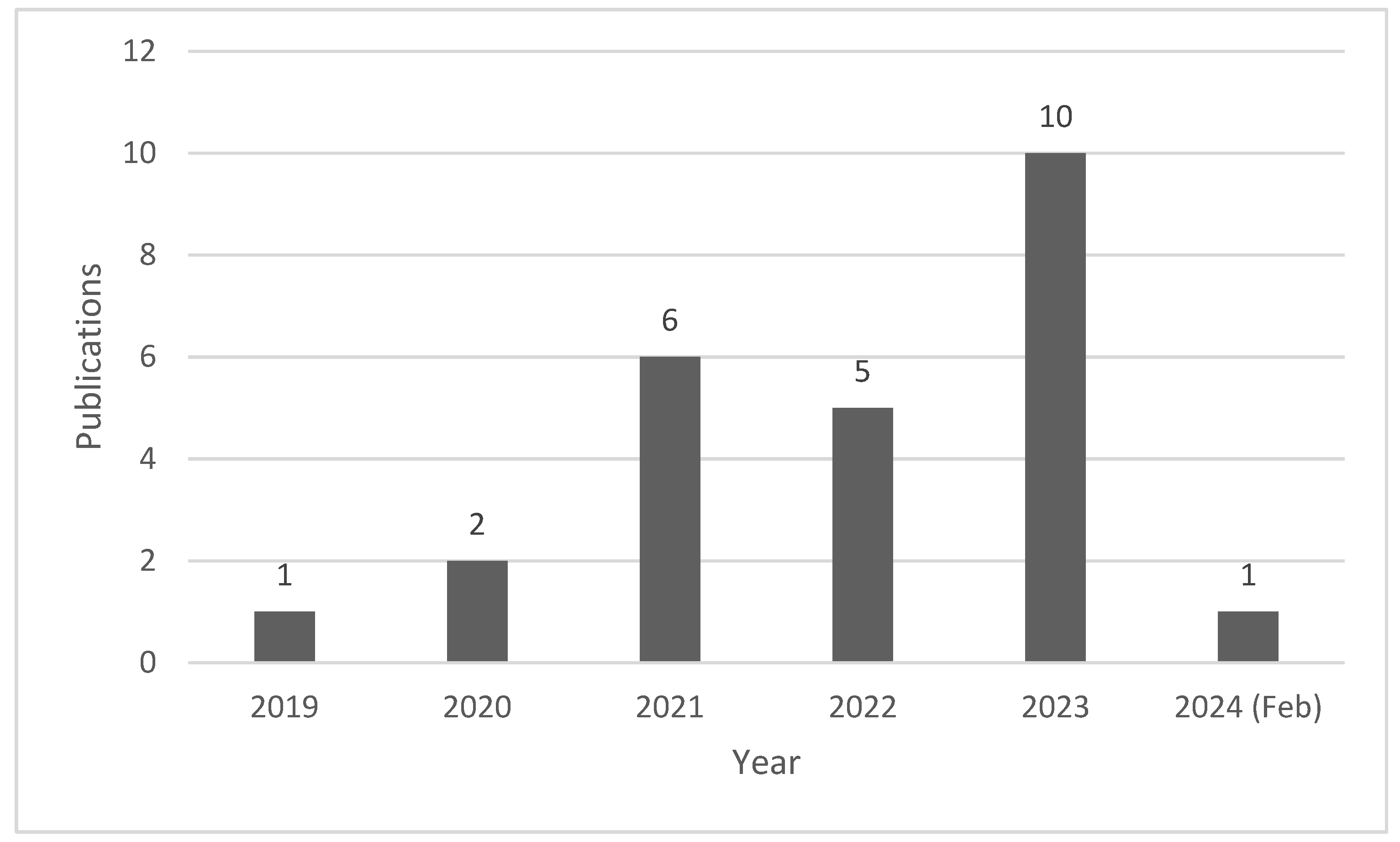

4.1. Topic Popularity

4.2. Research Methods

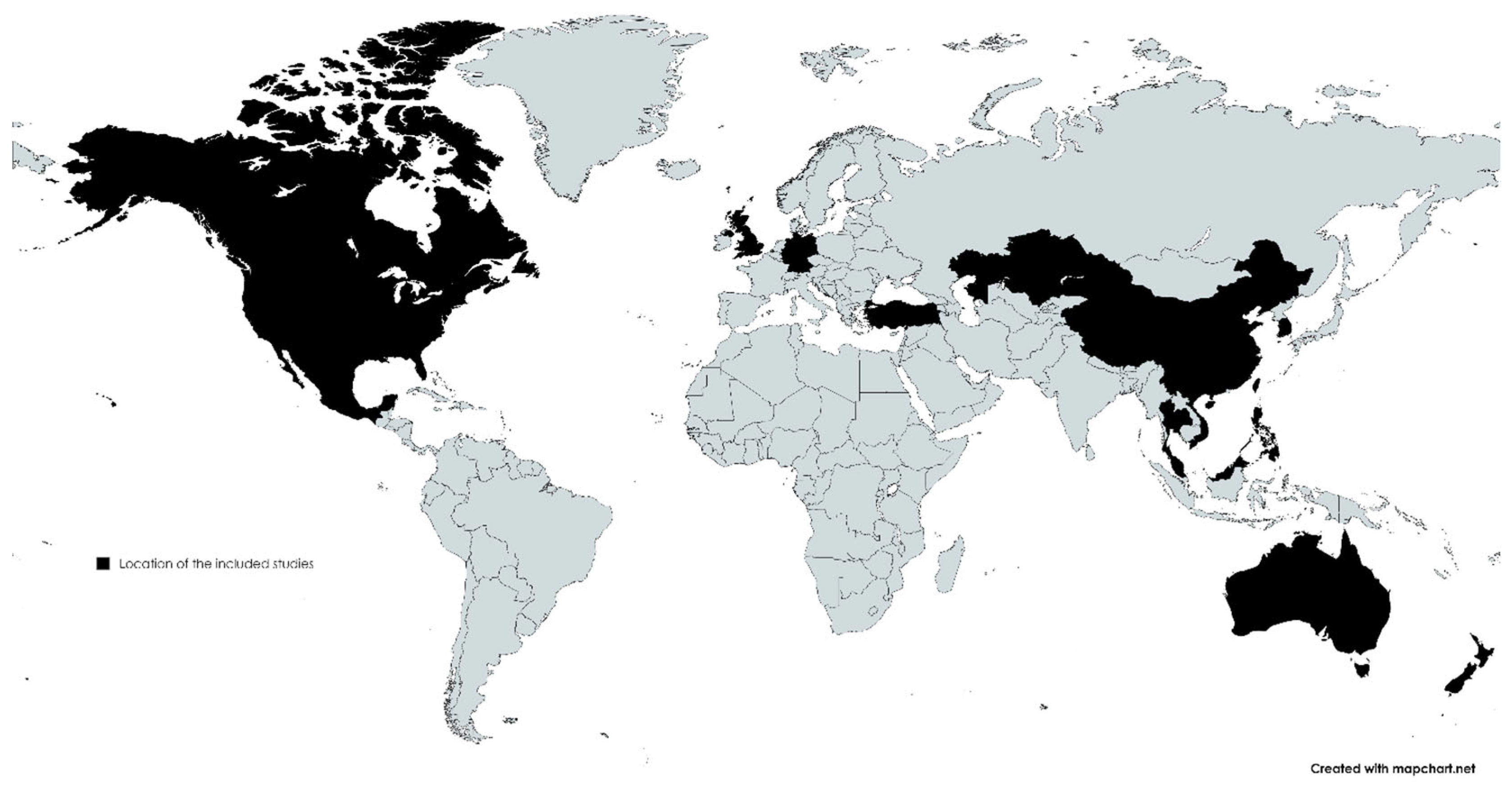

4.3. Geographic and Discipline Contexts

4.4. Theoretical Frameworks

4.5. Digital Technology Focus of the Study’s Design

4.6. Social Bounded, Informational Bounded or Integrated Conceptions

- Social bounded—study describes AHS as human-to-human or digitally mediated human-to-human and incorporates related AHS frameworks, methods and help sources.

- Informational bounded—study describes AHS as seeking information from digital sources only.

- Integrated—study describes AHS as inclusive of human-to-human and human-to-non-human and incorporates an integrated framework of AHS or a mix of frameworks, methods and help sources that suggest an integrated interpretation.

4.7. Sources of Help

5. Discussion

5.1. Q1: What Is the Nature of Contemporary HE AHS Literature Containing a Digital Aspect?

5.2. Q2: To What Extent Are These Studies Grounded in Theory and How Are These Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks Described?

5.3. Q3: Which Sources (Or Resources) of Help Are Identified Across This Literature?

5.4. Critical Analysis of Research Trends

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHS | Academic help-seeking |

| HE | Higher Education |

| SRL | Self-regulated learning |

| VLE | Virtual learning environment |

| DC | Digital creation |

| DR | Digital resources |

| DE | Digital environment |

| MSLQ | Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire |

| OSLQ | Online Self-regulated Learning Questionnaire |

References

- Acosta-Gonzaga, E., & Ramirez-Arellano, A. (2021). The influence of motivation, emotions, cognition, and metacognition on students’ learning performance: A comparative study in higher education in blended and traditional contexts. SAGE Open, 11(2), 21582440211027561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D., Chuah, K. M., Devadason, E., & Azzis, M. S. A. (2023). From novice to navigator: Students’ academic help-seeking behaviour, readiness, and perceived usefulness of ChatGPT in learning. Education and Information Technologies, 29(11), 13617–13634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghaslah, D., & Alsayari, A. (2022). Academic help-seeking behaviours of undergraduate pharmacy students in Saudi Arabia: Usage and helpfulness of resources. Healthcare, 10(7), 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J., Oh, J., & Park, K. (2022). Self-regulated learning strategies for nursing students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H., & O’malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M. (2018). Are digital natives open to change? Examining flexible thinking and resistance to change. Computers & Education, 121, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S. L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrot, J. S., Llenares, I. I., & Del Rosario, L. S. (2021). Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7321–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Why ‘what works’ still won’t work: From evidence-based education to value-based education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29(5), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettle, A., & Grant, M. M. (2004). Finding the evidence for practice: A workbook for health professionals. Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, J. (2017). Comparing online and blended learner’s self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J., & Howe, W. D. (2023). Help-seeking matters for online learners who are unconfident. Distance Education, 44(1), 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J., & Lodge, J. (2021). Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help seeking behaviours: A comparison of online and blended learner perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, T. H., Kaur, A., & Trang Vu, M. (2022). Effectiveness of technology-integrated project-based approach for self-regulated learning of engineering students. European Journal of Engineering Education, 47(4), 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, H., Premkumar, K., & Acharibasam, J. W. (2020). Using an innovative intervention to promote active learning in an introductory microbiology course. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(2), n2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Y., & Hwang, G. J. (2019). An IRS-facilitated collective issue-quest approach to enhancing students’ learning achievement, self-regulation and collective efficacy in flipped classrooms. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(4), 1996–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C. Y., & Chang, C. H. (2021). Developing adaptive help-seeking regulation mechanisms for different help-seeking tendencies. Educational Technology & Society, 24(4), 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, H., Hayward, G., Wright, S., Edwards, A., Lunt, I., Mills, D., & Yu, K. (2008). The student learning experience in higher education: Literature review report for the Higher Education Academy. The Higher Education Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza Puga, D. S., & Aguilar, M. S. (2023). Students’ perspectives on using youtube as a source of mathematical help: The case of ‘julioprofe’. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 54(6), 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenhouse, D., Kandakatla, R., Berger, E., Rhoads, J. F., & DeBoer, J. (2020). Motivators and barriers in undergraduate mechanical engineering students’ use of learning resources. European Journal of Engineering Education, 45(6), 879–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C. J., Gonzales, C., Hill-Troglin Cox, C., & Shinn, H. B. (2023). Academic help-seeking and achievement of postsecondary students: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblin, J., Stefaniak, J., Eckhoff, A., & Luo, T. (2021). An exploration of factors influencing the decision-making process and selection of academic help sources. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 33(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, I. (2023). Quality of digital learning experiences–effective, efficient, and appealing designs? International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 40(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E. R., Thomas, H. G., & Heinrich, E. (2022). ‘A sense of community and camaraderie’: Increasing student engagement by supplementing an LMS with a Learning Commons Communication Tool. Active Learning in Higher Education, 25(2), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabenick, S. A. (2003). Seeking help in large college classes: A person-centered approach. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28(1), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabenick, S. A., & Dembo, M. H. (2011). Understanding and facilitating self-regulated help seeking. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(126), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabenick, S. A., & Knapp, J. R. (1988). Help seeking and the need for academic assistance. Journal of educational psychology, 80(3), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, J. A., & Karabenick, S. A. (1998). Help seeking in the information age. In S. A. Karabenick (Ed.), Strategic help seeking. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Maclaren, P. (2017). How is that done? Student views on resources used outside the engineering classroom. European Journal of Engineering Education, 43(4), 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makara, K. A., & Karabenick, S. A. (2013). Characterizing sources of academic help in the age of expanding educational technology: A new conceptual framework. In Advances in help-seeking research and applications: The role of emerging technologies (pp. 37–72). IAP Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Meşe, E., & Mede, E. (2023). Using digital differentiation to improve EFL achievement and self-regulation of tertiary learners: The Turkish context. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(2), 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micari, M., & Calkins, S. (2021). Is it OK to ask? The impact of instructor openness to questions on student help-seeking and academic outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(2), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A., Sibson, R., & Jackson, D. (2022). Digital demand and digital deficit: Conceptualising digital literacy and gauging proficiency among higher education students. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 44(3), 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Le Gall, S. (1981). Help-seeking: An understudied problem-solving skill in children. Developmental Review, 1(3), 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Le Gall, S. (1985). Chapter 2: Help-seeking behavior in learning. Review of Research in Education, 12(1), 55–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onah, D. F., Pang, E. L., & Sinclair, J. E. (2022). Investigating self-regulation in the context of a blended learning computing course. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 39(1), 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, A., & Akçapınar, G. (2023). Investigating the effect of prompts on learners’ academic Help-Seeking behaviours on the basis of learning analytics. Education and Information Technologies, 28(12), 16909–16934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamitsiou, Z., & Economides, A. A. (2021). The impact of on-demand metacognitive help on effortful behaviour: A longitudinal study using task-related visual analytics. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(1), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puustinen, M., & Rouet, J. F. (2009). Learning with new technologies: Help seeking and information searching revisited. Computers & Education, 53(4), 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzitskaya, Y., & Islamov, A. (2024). Nanolearning approach in developing professional competencies of modern students: Impact on self-regulation development. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(3), 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P. M., & Sperling, R. A. (2015). A comparison of technologically mediated and face-to-face help-seeking sources. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, R., Lee, Y., Berger, E. J., Rhoads, J., & Deboer, J. (2023). Collaborative engagement and help-seeking behaviors in engineering asynchronous online discussions. International Journal of Engineering Education, 39(1), 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A. M., Pintrich, P. R., & Midgley, C. (2001). Avoiding seeking help in the classroom: Who and why? Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlusche, C., Schnaubert, L., & Bodemer, D. (2023). Understanding students’ academic help-seeking on digital devices—A qualitative analysis. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 18, 017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R., & Benfield, G. (2005). The student experience of E-learning in higher education: A review of the literature. Brookes eJournal of Learning and Teaching, 1(3), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. E., & Storrs, H. (2023). Digital literacies, social media, and undergraduate learning: What do students think they need to know? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumadyo, M., Santoso, H. B., Sensuse, D. I., & Suhartanto, H. (2021). Metacognitive aspects influencing help-seeking behavior on collaborative online learning environment: A systematic literature review. Journal of Educators Online, 18(3), n3. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1320666 (accessed on 1 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. (2020). Scoping reviews in health professions education: Challenges, considerations and lessons learned about epistemology and methodology. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(4), 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, J. (2020). The digital divide. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Viriya, C. (2022). Exploring the impact of synchronous, asynchronous, and bichronous online learning modes on EFL students’ self-regulated and perceived english language learning. Reflections, 29(1), 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Li, S., Tan, C., Zhang, J., & Lajoie, S. P. (2023). Cognitive load patterns affect temporal dynamics of self-regulated learning behaviors, metacogntive judgments, and learning achievements. Computers and Education, 207, 104924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Y. (2021). Learning analytics on structured and unstructured heterogeneous data sources: Perspectives from procrastination, help-seeking, and machine-learning defined cognitive engagement. Computers and Education, 163, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, H. K., & Chan, C. F. (2023). The investigation of Hong Kong university engineering students’ perception of help-seeking with attitudes towards learning simulation software. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 22(1), 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Cheng, J., Lei, J., & Wang, Q. (2023). Facilitating student engagement in large lecture classes through a digital question board. Education and Information Technologies, 28(2), 2091–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Xu, Q., Koehler, A. A., & Newby, T. (2023b). Comparing blended and online learners’ self-efficacy, self-regulation, and actual learning in the context of educational technology. Online Learning Journal, 27(4), 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of educational psychology, 81(3), 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term and Variations | Boolean Operators |

|---|---|

| (“help seeking” OR “help-seeking”) | AND |

| (“digital” OR “technolog*”) |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| AHS as a focus | HS in a clinical context |

| Some exploration of the relationship between digital technology and AHS | No exploration of digital technology and AHS relationship |

| University undergraduate participants | School student participants |

| Articles published from 2019 (last 5 years) | Articles published before 2019 |

| Written in English | Written in any other language |

| Peer reviewed journal articles | Grey literature, reviews, and thesis |

| References | Title | Objective | Participants | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Acosta-Gonzaga & Ramirez-Arellano, 2021) | The influence of motivation, emotions, cognition, and metacognition on students’ learning performance: A comparative study in higher Education in Blended and Traditional Contexts | To compare the relationships between motivation, emotions, cognition, metacognition and students’ academic achievements across face-to-face and a blended learning context. | 222 management and industrial engineering students and 116 biology students | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, survey, data traces, exam |

| (Adams et al., 2023) | From novice to navigator: Students’ academic help-seeking behaviour, readiness, and perceived usefulness of ChatGPT in learning | Investigate students’ readiness to use ChatGPT, and its perceived usefulness for academic purposes. | 373 students from different fields | Mixed: survey |

| (An et al., 2022) | Self-regulated learning strategies for nursing students: A pilot randomised controlled trial | Compare the effects of the use of augmented reality as an innovative learning method and the use of a textbook as a conventional learning method. | 62 nursing students from two universities | Quantitative: experimental, survey |

| (Barrot et al., 2021) | Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines | Investigate the challenges and specific strategies that students employed to overcome them during COVID-19 enforced online learning. | 200 students across psychology, physical education, and sports management | Mixed: survey, focus group |

| (Broadbent & Lodge, 2021) | Use of live chat in higher education to support self-regulated help seeking behaviours: a comparison of online and blended learner perspectives | Explore the use of live chat technology for online academic help-seeking within higher education focusing on any differences between online or blended learning student perspectives. | 246 psychology students | Mixed: survey |

| (Bui et al., 2022) | Effectiveness of technology-integrated project-based approach for self-regulated learning of engineering students | Explore the impact of a technology-integrated project-based learning intervention (ReaLabs) on students’ learning attitudes, behaviours and self-regulated learning. | 99 engineering students | Quantitative: experimental, survey |

| (Bull et al., 2020) | Using an innovative intervention to promote active learning in an introductory microbiology course | Measure the impact of a group PowerPoint poster creation activity on learning approaches, and content retention, as well as detect attitudes and actions consistent with increasing student engagement. | 238 microbiology students | Mixed: quasi-experimental, focus group, survey |

| (Chen & Hwang, 2019) | An IRS-facilitated collective issue-quest approach to enhancing students’ learning achievement, self-regulation and collective efficacy in flipped classrooms | Investigate the impacts of an Instant Response System (Kahoot!) facilitated collective issue-quest strategy on students’ learning achievement, self-regulation, learning satisfaction and collective efficacy. | 85 internet marketing students | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, survey |

| (Chou & Chang, 2021) | Developing adaptive help-seeking regulation mechanisms for different help-seeking tendencies | Propose an approach for identifying students’ different help-seeking tendencies and evaluate the effect of adaptive AHS regulation on students’ AHS and learning performance. | 52 computer science students | Quantitative: experimental, test, survey |

| (Esparza Puga & Aguilar, 2023) | Students’ perspectives on using YouTube as a source of mathematical help: the case of ‘julioprofe’ | Explore students’ perspectives on the use of videos from the YouTube channel julioprofe as a source of mathematical help. | 22 engineering students | Qualitative: focus group |

| (Evenhouse et al., 2020) | Motivators and barriers in undergraduate mechanical engineering students’ use of learning resources | Examine the motivators and barriers impacting students’ choices to engage with class-provided learning resources. | 26 engineering dynamics students | Qualitative: interview |

| (Kahu et al., 2022) | ‘A sense of community and camaraderie’: Increasing student engagement by supplementing an LMS with a Learning Commons Communication Tool | Gain an in-depth understanding of how Discord and Microsoft Teams work in conjunction with an LMS to benefit student engagement and learning. | 19 students within a computer sciences and information technology department | Qualitative: interview |

| (Meşe & Mede, 2023) | Using digital differentiation to improve EFL achievement and self-regulation of tertiary learners: the Turkish context | Explore the effect of Differentiated Instruction on students’ English Foreign Language achievement in terms of speaking proficiency and SRL in an intact classroom. | 31 English as foreign language students | Mixed: quasi-experimental, test, survey, focus group |

| (Onah et al., 2022) | Investigating self-regulation in the context of a blended learning computing course | Investigate aspects of blended MOOC usage in the context of a computing course. | 27 then 17 students in computer security | Quantitative: survey |

| (Önder & Akçapınar, 2023) | Investigating the effect of prompts on learners’ academic help-seeking behaviours on the basis of learning analytics | Examine the effect of prompts (meaning questions or elicitations that aim to encourage learning strategies that students are capable of but do not show spontaneously) on fostering learners’ online AHS behaviour using learning analytics approaches. | 39 online robotic programming students | Quantitative: experimental, data logs |

| (Papamitsiou & Economides, 2021) | The impact of on-demand metacognitive help on effortful behaviour: A longitudinal study using task-related visual analytics | Investigate changes in learners’ effortful behaviour over time, due to receiving metacognitive help in the form of task-related visual analytics. | 67 students on a management information systems course, took part in all 4 phases (more overall) | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, test |

| (Radzitskaya & Islamov, 2024) | Nanolearning approach in developing professional competencies of modern students: Impact on self-regulation development | Determine nanolearning effectiveness in the context of students’ self-regulation development. | 120 sociology students | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, test, survey |

| (Rothstein et al., 2023) | Collaborative engagement and help-seeking behaviours in engineering asynchronous online discussions | Investigate the ways students use discussion forums to engage with their peers and course material, how this contributes to a sense of community and whether this is sufficient to facilitate group and individual knowledge acquisition. | 796 engineering students | Qualitative: discussion forum posts |

| (Schlusche et al., 2023) | Understanding students’ academic help-seeking on digital devices—a qualitative analysis | Determine requirements for the design of digital services that support asking for and receiving help. | 59 students mostly from media informatics and psychology | Qualitative: interview |

| (Viriya, 2022) | Exploring the impact of synchronous, asynchronous, and bichronous online learning modes on EFL students’ self-regulated and perceived English language learning | Investigate the influences of synchronous, asynchronous, and bichronous learning modes on students’ self-regulated and perceived learning when learning English language online. | 142 foundation English students | Mixed: survey, learning diary |

| (Wang et al., 2023) | Cognitive load patterns affect temporal dynamics of self-regulated learning behaviours, metacogntive judgments, and learning achievements | Investigate how students’ cognitive load patterns relate to their self-regulated learning and performance. | 111 medical students | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, data logs, test |

| (Wu, 2021) | Learning analytics on structured and unstructured heterogeneous data sources: Perspectives from procrastination, help-seeking, and machine-learning defined cognitive engagement | Investigate how students’ demographic characteristics, motivational tendencies, and their cognitive engagement in meaningful statistics learning on Facebook are associated with their academic achievement. | 78 advanced statistics students | Quantitative: survey, machine learning categorised and counted posts, test |

| (Yau & Chan, 2023) | The investigation of Hong Kong university engineering students’ perception of help-seeking with attitudes towards learning simulation software | Investigate students’ help-seeking perceptions and attitudes towards learning simulation software. | 127 engineering students | Quantitative: survey |

| (L. Zhang et al., 2023) | Facilitating student engagement in large lecture classes through a digital question board | Explore how the presence of a digital question board influences students’ cognitive engagement and emotional engagement. | 253 introductory research methodology students | Mixed: quasi-experimental, survey, interview, observation, online posts |

| (Z. Zhang et al., 2023) | Comparing blended and online learners’ self-efficacy, self-regulation, and actual learning in the context of educational technology | Investigate disparities in learning among preservice teachers in the realm of educational technology, specifically in relation to different learning modes (blended vs. fully online). | 325 pre-service teachers | Quantitative: quasi-experimental, survey |

| Digital Focus of the Study’s Design | Conception of AHS | Sources of Help Reported | Country/Region | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC—PowerPoint poster creation | Social | Peers, instructors and teaching assistants | Canada | (Bull et al., 2020) |

| DE—online differentiated instruction | Social | Peers and tutors via Zoom | Turkey | (Meşe & Mede, 2023) |

| DE—blended compared to traditional | Social | None explicitly given (assumption that AHS is provided through the Moodle virtual learning environment tools) | Mexico | (Acosta-Gonzaga & Ramirez-Arellano, 2021) |

| DE—compared three modes of online learning | Social | Face-to-face friends, tutors, peers or family members, online call or live chat, instructors through email and messages | Thailand | (Viriya, 2022) |

| DE—digitally rich environment | Integrated | Lecturers, teaching assistant help room, peers, digital messaging, social media blog, discussion forum, course solution videos and digital lecture book | Turkey | (Evenhouse et al., 2020) |

| DE—emergency distance learning | Integrated | Internet, Facebook groups, family members, home resources and teachers | Philippines | (Barrot et al., 2021) |

| DE—online and blended mode comparison on a digital skills course | Social | Peers, instructors, and teaching assistants in the course | USA | (Z. Zhang et al., 2023) |

| DE—tracking of interactions in Bioworld intelligent tutoring system | Information | Course documents and programme library | China | (Wang et al., 2023) |

| DR—LiveChat system in two contexts, fully online and blended | Social | LiveChat system, email and discussion board | Australia | (Broadbent & Lodge, 2021) |

| DR—simulation software (FlexSim and Arena) | Integrated | Calling, emailing, asking face-to-face or on live chat or posting question on discussion board to instructor or peers and ‘proper’ website support | Hong Kong | (Yau & Chan, 2023) |

| DR—adaptive computer assisted learning system | Integrated | Computer assisted learning system | Taiwan | (Chou & Chang, 2021) |

| DR—asynchronous online discussions | Social | Discussion board | USA | (Rothstein et al., 2023) |

| DR—augmented reality compared to a textbook as a method to support SRL | Integrated | Augmented reality app and textbook | Korea | (An et al., 2022) |

| DR—computer mediated communication tools | Integrated | Instant messenger, WhatsApp, bulletin board, Moodle, document exchange service, Facebook | Germany | (Schlusche et al., 2023) |

| DR—digital AHS prompts | Integrated | Digital AHS prompts, lecture recordings, recommended resources, discussion forums, and synchronous sessions | Turkey | (Önder & Akçapınar, 2023) |

| DR—Discord, Microsoft Teams and a learning management system | Social | Peers and instructors through the Discord and Teams communication tools | New Zealand | (Kahu et al., 2022) |

| DR—Facebook community | Social | Facebook mediated peer and instructor help | Taiwan | (Wu, 2021) |

| DR—Kahoot integration in a flipped classroom | Integrated | Kahoot, peers and internet | Taiwan | (Chen & Hwang, 2019) |

| DR—massively open online course as online aspect of blended learning | Social | Massively Open Online Course (MOOC) | UK | (Onah et al., 2022) |

| DR—Padlet backchannel | Social | Peers and lecturers in class and on a Padlet | China | (L. Zhang et al., 2023) |

| DR—ReaLabs software | Social | ReaLabs software and Google Docs | Vietnam | (Bui et al., 2022) |

| DR—students’ readiness and perceived usefulness of ChatGPT for learning | Integrated | ChatGPT | Malaysia | (Adams et al., 2023) |

| DR—task related visual analytics to aid AHS | Integrated | Task visualisations | European university | (Papamitsiou & Economides, 2021) |

| DR—TikTok video support as part of microlearning approach | Social | Video, social media and TikTok | Republic of Kazakhstan | (Radzitskaya & Islamov, 2024) |

| DR—YouTube channel (Julioprofe) | Integrated | YouTube (Julieprofe channel) | Mexico | (Esparza Puga & Aguilar, 2023) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillies, C.; Turner, J. Looking for Answers: A Scoping Review of Academic Help-Seeking in Digital Higher Education Research. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091095

Gillies C, Turner J. Looking for Answers: A Scoping Review of Academic Help-Seeking in Digital Higher Education Research. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091095

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillies, Chris, and Jim Turner. 2025. "Looking for Answers: A Scoping Review of Academic Help-Seeking in Digital Higher Education Research" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091095

APA StyleGillies, C., & Turner, J. (2025). Looking for Answers: A Scoping Review of Academic Help-Seeking in Digital Higher Education Research. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091095