Toward Sustainable Digital Literacy: A Comparative Study of Gamified and Non-Gamified Digital Board Games in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Digital Literacy

2.2. Gamification for Education

2.3. Digital Board Game

2.4. Conceptual Model

3. Objective of Study

- RQ1: How does the implementation of a digital board game affect knowledge acquisition in digital literacy among students in gamified versus non-gamified learning environments?

- RQ2: What are the differences in game engagement between students interacting with the gamified and non-gamified versions of the digital board game?

- RQ3: What behavioral outcomes emerge from the use of a gamified digital board game compared to a non-gamified version, and how do these outcomes reflect digital literacy learning?

- H1: Students using the gamified version of the digital board game will exhibit significantly higher levels of digital literacy knowledge acquisition than those using the non-gamified version, demonstrating the effectiveness of gamification in learning.

- H2: Engagement levels, as measured by the Game Engagement Questionnaire (GEQ), will be significantly higher in the experimental group (gamified) compared to the control group (non-gamified), indicating the motivational impact of gamification elements.

- H3: Behavioral outcomes, including increased motivation, persistence, and application of digital literacy skills, will be more pronounced in students interacting with the gamified digital board game, highlighting the behavioral benefits of gamification in educational contexts.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample of Participants

4.2. Instruments

4.2.1. Game Engagement Questionnaire

4.2.2. Digital Literacy Assessment

4.2.3. Game Analytics

4.2.4. Design of Board Game for Digital Literacy

4.2.5. Design of Board Game for Non-Gamified and Gamified Digital Board Games

4.2.6. Research Procedure

5. Results and Data Analysis

5.1. Results of Digital Literacy Assessment

5.2. Results of Game Engagement Questionnaire

5.3. Result of Game Analytics

6. Discussion

6.1. Impact of Gamification on Knowledge Acquisition

6.2. Influence of Gamification on Engagement and Motivation

6.3. Behavioral Outcomes and Student Interaction Patterns

6.4. Limitations

7. Conclusions

8. Research Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GEQ | Game Engagement Questionnaire |

| ICT | Information and Communications Technology |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

References

- Aarsand, P. (2019). Categorization activities in Norwegian preschools: Digital tools in identifying, articulating, and assessing. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agca, R. K., & Özdemir, S. (2013). Foreign language vocabulary learning with mobile technologies. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 83, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z., Ghazali, M. a. I. M., Ismail, R., Muhammad, N. N., Abidin, N. a. Z., & Malek, N. A. (2018). Digital board game: Is there a need for it in language learning among tertiary level students? MATEC Web of Conferences, 150, 05026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkurdi, S. (2021). Gamification in knowledge management: Increasing motivation to share knowledge using cooperation and inter-team competition. The Claremont Graduate University. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qallaf, C. L., & Al-Mutairi, A. S. (2016). Digital literacy and digital content supports learning. The Electronic Library, 34(3), 522–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawaier, R. S. (2018). The effect of gamification on motivation and engagement. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(1), 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D., & Raichel, N. (2020). Enhancing perceived digital literacy skills and creative self-concept through gamified learning environments: Insights from a longitudinal study. International Journal of Educational Research, 101, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo, L., Liao, R., Kishore, R., & Rao, H. R. (2020). Effects of structural and trait competitiveness stimulated by points and leaderboards on user engagement and performance growth: A natural experiment with gamification in an informal learning environment. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(6), 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P., & Sofkova-Hashemi, S. (2016). Screen-based literacy practices in Swedish primary schools. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 11(2), 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleya-García, E., & Miralles, L. (2022). ‘The Game of the Sea’: An interdisciplinary educational board game on the marine environment and ocean awareness for primary and secondary students. Education Sciences, 12(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bíró, G. I. (2014). Didactics 2.0: A pedagogical analysis of gamification theory from a comparative perspective with a special view to the components of learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 141, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghian, I., Cojocariu, V. M., Popescu, C. V., & Mâţӑ, L. (2019). Game-based learning. Using board games in adult—ProQuest. Journal of Educational Sciences and Psychology, 9(1), 51–57. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/game-based-learning-using-board-games-adult/docview/2302388679/se-2 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bovermann, K., & Bastiaens, T. (2018). Using gamification to foster intrinsic motivation and collaborative learning: A comparative testing. In Proceedings of EdMedia: World conference on educational media and technology (pp. 1128–1137). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/184321/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Brockmyer, J. H., Fox, C. M., Curtiss, K. A., McBroom, E., Burkhart, K. M., & Pidruzny, J. N. (2009). The development of the Game Engagement Questionnaire: A measure of engagement in video game-playing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinot, A., & Fairfield, J. A. (2019). Game-Based learning to engage students with physics and astronomy using a board game. International Journal of Game-Based Learning, 9(1), 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. C. (2004). Apply problem-based learning on sharable health education learning material [Master’s Thesis, Taipei Medical University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C., & Yang, S. (2024). Learners’ positive and negative emotion, various cognitive processing, and cognitive effectiveness and efficiency in situated task-centered digital game-based learning with different scaffolds. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(9), 5058–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiotaki, D., Poulopoulos, V., & Karpouzis, K. (2023). Adaptive game-based learning in education: A systematic review. Frontiers in Computer Science, 5, 1062350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, N. (2020). Development of students’ digital literacy skills through digital storytelling with mobile devices. Educational Media International, 57(3), 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Júnior, J. N., Leite, A. J. M., Junior, Winum, J., Basso, A., De Sousa, U. S., Nascimento, D. M. D., & Alves, S. M. (2021). HSG400—Design, implementation, and evaluation of a hybrid board game for aiding chemistry and chemical engineering students in the review of stereochemistry during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers, 36, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanzadeh, H., Farrokhnia, M., Dehghanzadeh, H., Taghipour, K., & Noroozi, O. (2023). Using gamification to support learning in K-12 education: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(1), 34–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, A. E., & Alanyalı Aral, E. (2025). Board game as a participatory design technique for urban spaces: A ludological analysis. Simulation & Gaming. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, P., McDonald, F., Empson, R., Kelly, P., & Petersen, A. (2018, April 21–26). Empirical support for a causal relationship between gamification and learning outcomes. CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13), Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, M. J., Aciego, J. J., Gonzalez-Prieto, I., Carrillo-Rios, J., Gonzalez-Prieto, A., & Claros-Colome, A. (2024). A gamified active-learning proposal for higher-education heterogeneous STEM courses. Education Sciences, 15(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D. S., Zemski, A., Enticott, J., & Barton, C. (2021). Tabletop board game elements and gamification interventions for health behavior change: Realist review and proposal of a game design framework. JMIR Serious Games, 9(1), e23302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezezika, O., Fusaro, M., Rebello, J., & Aslemand, A. (2023). The pedagogical impact of board games in public health biology education: The Bioracer Board Game. Journal of Biological Education, 57(2), 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, F. F., & Taghizadeh, M. (2022). Comparing the effects of digital and non-digital gamification on EFL learners’ collocation knowledge, perceptions, and sense of flow. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(7), 2083–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N. N. H., Harun, N. N. O., Ariffin, N. N. A., & Abdullah, N. N. A. C. (2023). Gamification using board game approach in science education—A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology, 33(3), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B., Hew, K. F., & Lo, C. K. (2019). Investigating the effects of gamification-enhanced flipped learning on undergraduate students’ behavioral and cognitive engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, I. (2018). Digital literacy in the workplace. Business Information Review, 35(2), 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansukpum, K., Chernbumroong, S., Intawong, K., Sureephong, P., & Puritat, K. (2024). Gamified virtual reality for library services: The effect of gamification on enhancing knowledge retention and user engagement. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 31(1), 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2378737 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Karakose, T., Polat, H., & Papadakis, S. (2021). Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(23), 13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A., Bouzidi, R., & Nader, F. (2023). Gamification of e-learning in higher education: A systematic literature review. Smart Learning Environments, 10(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., Yi, P., & Hong, J. I. (2021). Are schools digitally inclusive for all? Profiles of school digital inclusion using PISA 2018. Computers & Education, 170, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & Von Korflesch, H. F. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K., & Özpolat, K. (2020). The dark side of narrow gamification: Negative impact of assessment gamification on student performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanauskas, V. (2017). Reflections on education. Scientia Socialis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. W., Shih, M., Liang, J., & Tseng, Y. (2021). Investigating learners’ engagement and science learning outcomes in different designs of participatory simulated games. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(3), 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Hou, H., & Lin, W. (2022). Chemistry education board game based on cognitive mechanism: Multi-dimensional evaluation of learners’ knowledge acquisition, flow and playing experience of board game materials. Research in Science & Technological Education, 42(3), 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. K., Lin, Y., Wang, T., Su, L., & Huang, Y. (2021). Effects of incorporating augmented reality into a board game for high school students’ learning motivation and acceptance in health education. Sustainability, 13(6), 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, D. L., & Niederhauser, D. S. (2016). Digital literacies go to school: A cross-case analysis of the literacy practices used in a classroom-based social network site. Computers in the Schools, 33(2), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Li, X., & Santhanam, R. (2023). Gamification burnout: The unintended consequences of motivational design. Information & Management, 60(1), 103733. [Google Scholar]

- Llanos-Ruiz, D., Ausin-Villaverde, V., & Abella-Garcia, V. (2024). Interpersonal and intrapersonal skills for Sustainability in the educational Robotics classroom. Sustainability, 16(11), 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, M. L. (2018). Quasi-experimental design. Biostatistics & Epidemiology, 4(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, A. (2018). Preparing preservice educators to teach critical, place-based literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 61(4), 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muis, K. R., Denton, C., & Dubé, A. (2022). Identifying CRAAP on the Internet: A source evaluation intervention. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(7), 239–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A. M., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2023). Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), 373–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbanes, P. E. (2007). Monopoly: The world’s most famous game—And how it got that way. In Internet archive. Da Capo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Arranz, A., Er, E., Martínez-Monés, A., Bote-Lorenzo, M. L., Asensio-Pérez, J. I., & Muñoz-Cristóbal, J. A. (2019). Understanding student behavior and perceptions toward earning badges in a gamified MOOC. Universal Access in the Information Society, 18(3), 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, P., Gee, E., Tran, K., Aguilera, E., Cortés, L. E. P., Kessner, T., & Siyahhan, S. (2021). Board game design: An educational tool for understanding environmental issues. International Journal of Science Education, 43(13), 2148–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Kim, S. (2021). Leaderboard design principles to enhance learning and motivation in a gamified educational environment: Development study. JMIR Serious Games, 9(2), e14746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, F., Ceregini, A., Ivanov, S., Passarelli, M., Persico, D., & Volta, E. (2024). Digital vs. hybrid: Comparing two versions of a board game for teacher training. Education Sciences, 14(3), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premthaisong, S., & Srisawasdi, N. (2020, November 23–27). Supplementing elementary science learning with multi-player digital board game: A pilot study. 28th International Conference on Computers in Education, Virtual. Available online: https://v0.apsce.net/icce/icce2020/proceedings/W1-13/W4/ICCE2020-Proceedings-Vol2-W4_6.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Puritat, K. (2019). Enhanced knowledge and engagement of students through the gamification concept of game elements. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (IJEP), 9(5), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S., Yeung, S. S., Zainuddin, Z., Ng, D. T. K., & Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Examining the effects of mixed and non-digital gamification on students’ learning performance, cognitive engagement and course satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(1), 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, D., Hogan, B., & Lalić, D. (2015). Overcoming digital divides in higher education: Digital literacy beyond Facebook. New Media & Society, 17(10), 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A., Shirmohammadi, S., Amer, I., & Hefeeda, M. (2025). A review of player engagement estimation in video games: Challenges and opportunities. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM), 21(7), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebhi, M., Ben Aissa, M., Tannoubi, A., Saidane, M., Guelmami, N., Puce, L., Chen, W., Chalghaf, N., Azaiez, F., Zghibi, M., & Bragazzi, N. L. (2023). Reliability and validity of the Arabic version of the game experience questionnaire: Pilot questionnaire study. JMIR Formative Research, 7, e42584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, D. R., Langer, M., & Kaur, R. (2020). Gamification in the classroom: Examining the impact of gamified quizzes on student learning. Computers & Education, 144, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, A. (2012). Design elements, color fundamentals: A graphic style manual for understanding how color affects design. Rockport. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, M. (2022). Gamifying Serious games: Modding modern board games to teach game potentials. In Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 254–272). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureephong, P., Chernbumroong, S., Niemsup, S., Homla, P., Intawong, K., & Puritat, K. (2024). Exploring the impact of the gamified metaverse on knowledge acquisition and library anxiety in academic libraries. Information Technology and Libraries, 43(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. W., Ng, K. B., & Mogali, S. R. (2022). An exploratory digital board game approach to the review and reinforcement of complex medical subjects like anatomical education: Cross-sectional and mixed methods study. JMIR Serious Games, 10(1), e33282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taspinar, B., Schmidt, W., & Schuhbauer, H. (2016). Gamification in Education: A board game approach to Knowledge acquisition. Procedia Computer Science, 99, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2020). Skills in the area of digital safety as a key component of digital literacy among teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 25(1), 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J., Liu, S., Chang, C., & Chen, S. (2021). Using a Board Game to Teach about Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 13(9), 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita-Barrull, N., Guzmán, N., Estrada-Plana, V., March-Llanes, J., Mayoral, M., & Moya-Higueras, J. (2022). Impact on executive dysfunctions of gamification and nongamification in playing board games in children at risk of social exclusion. Games for Health Journal, 11(1), 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannapiroon, N., & Pimdee, P. (2022). Thai undergraduate science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) creative thinking and innovation skill development: A conceptual model using a digital virtual classroom learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 27(4), 5689–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Chen, C., Wang, S., & Hou, H. (2018, July 8–13). The design and evaluation of a gamification teaching activity using board game and QR code for organic chemical structure and functional groups learning. 2022 12th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), Yonago, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., & Su, Y. (2025). The effect of learning computational thinking skills through educational board games on students’ cognitive styles, cognitive behaviors, and learning effectiveness. Asia Pacific Education Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., & Li, D. (2021). Understanding the dark side of gamification health management: A stress perspective. Information Processing & Management, 58(4), 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusa, N., & Hamada, R. (2023). Board game design to understand the national power mix. Education Sciences, 13(8), 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., & McClure, C. D. (2024). Gather.Town: A gamification tool to promote engagement and establish online learning communities for language learners. RELC Journal, 55(1), 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Cheng, I., & Chen, N. (2018, December 12–14). The effect of 3D electronic board game in enhancing elementary students learning performance on human internal organ. 2018 International Joint Conference on Information, Media and Engineering (ICIME) (pp. 225–230), Osaka, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Board Game Name | Objective | Gamification Application | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zheng et al. (2018) | The Organ Savior Game | To teach elementary school students about health and physical education | No | This study showed that students improved their academic performance when they studied health knowledge and human internal organs (Zheng et al., 2018). |

| Ali et al. (2018) | N/A | To teach university students about learning the English language | No | Most of the participants considered that playing digital board games helped them develop their vocabulary. Rather than having the pupils memorize new terminology, they might explore it by playing a digital board game (Ali et al., 2018). |

| Da Silva Júnior et al. (2021) | Reactions | To educate students about organic reactions | No | This form of game would be a useful teaching aid for helping students understand chemical responses in greater detail (Da Silva Júnior et al., 2021). |

| Tsai et al. (2021) | Be Blessed Taiwan | To educate high school students about sustainable development | No | There was a significant improvement in students’ scores, particularly in biodiversity and biological conservation concepts. The results highlighted the difficulty students faced in achieving all four ESD goals through gameplay (Tsai et al., 2021). |

| Parekh et al. (2021) | Pollutaplop | To engage young people in understanding environmental issues | No | Creating board games in authentic contexts helped youths develop models and systems thinking. Enthusiastic gamers, including youths, may be particularly well-suited to grasping the complexities of both games and their real-world contexts (Parekh et al., 2021). |

| Li et al. (2022) | Chemistry | To enhance students’ understanding of how elements combine to form chemical compounds | No | Playing the game improved students’ grasp of element combination concepts. Students showed high engagement with and acceptance of the game, particularly when it featured components made from different materials (Li et al., 2022). |

| Cardinot and Fairfield (2019) | N/A | To support the teaching and learning of astronomical themes from the new Irish Science Syllabus | No | The outcomes demonstrated how much the game enhanced students’ attitudes toward scientists and their comprehension of astronomy subjects. The game was shown to be a useful teaching tool and a way to improve social skills (Cardinot & Fairfield, 2019). |

| Vita-Barrull et al. (2022) | N/A | To educate high school students in the chemical course | Yes | Students in the gamified learning activity outperformed those in the lecture-based teaching approach regarding the achievement of learning objectives (Vita-Barrull et al., 2022). |

| Vita-Barrull et al. (2022) | N/A | To assess how gamification affects the executive function behaviors of students who are prone to social exclusion | Yes | The outcomes showed a major decrease in behavioral difficulties related to executive functions between pre-intervention and post-intervention. The non-gamified group mostly accounted for the observed decrease (Vita-Barrull et al., 2022). |

| Arboleya-García and Miralles (2022) | The Game of the Sea | To educate primary and secondary students on the fundamentals of marine ecology | Yes | Children and adults’ awareness of the marine environment improved, with young people showing a slightly greater improvement and the game teaching its players how valuable the marine environment is and the significance of conserving it (Arboleya-García & Miralles, 2022). |

| Yusa and Hamada (2023) | N/A | To teach and learn about the optimal mix of national power sources on energy and sustainability courses in higher education | No | Students expressed great enjoyment of the game and confirmed its potential as a useful tool for energy and environmental studies in high schools and colleges, according to a post-game survey (Yusa & Hamada, 2023). |

| Game Elements | Definition | Description in Board Game | Learning Objective | Gamified | Non- Gamified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board progression | A structured path that guides player movement and task sequencing (Oliveira et al., 2023). | A standard board game mechanic using a path-based layout, where each move advances the player to a specific task square. | Enhances competence by allowing learners to see progress and complete tasks in stages. | Yes | Yes |

| Randomness | Unpredictable outcomes introduced via dice rolls or randomized card draws (Demirel & Alanyalı Aral, 2025). | A standard mechanic in board games, introducing variability and simulating real-world unpredictability in digital decision-making. | Stimulates curiosity and situational engagement, helping students manage decision-making under uncertainty. | Yes | Yes |

| Leaderboard | A visual display of players’ rankings based on their performance (Oliveira et al., 2023). | Real-time rankings and scores, motivating players to strive for higher positions and enabling competition among groups. | Promotes extrinsic motivation, competence, and social comparison, potentially increasing persistence and goal striving. | Yes | No |

| Avatar | A graphical representation that a player can customize to represent themselves in the game (Oliveira et al., 2023). | Players can choose and customize avatars, personalizing their gaming experience and expressing their identity. | Fosters autonomy and self-expression, enhancing emotional connection and intrinsic motivation. | Yes | No |

| Challenges | Specific tasks or objectives given to players to accomplish within the game (Khaldi et al., 2023). | Challenges are embedded throughout the game, requiring players to solve problems or complete tasks. | Supports competence and increases engagement through meaningful challenge. | Yes | No |

| Profiles | User-specific pages that track individual gaming history, preferences, and achievements (Krath et al., 2021). | Each player has a profile where their achievements and preferences are stored, enabling a tailored experience and facilitating progress tracking. | Supports relatedness and self-reflection, helping learners feel connected to the game and reinforcing ownership of learning. | Yes | No |

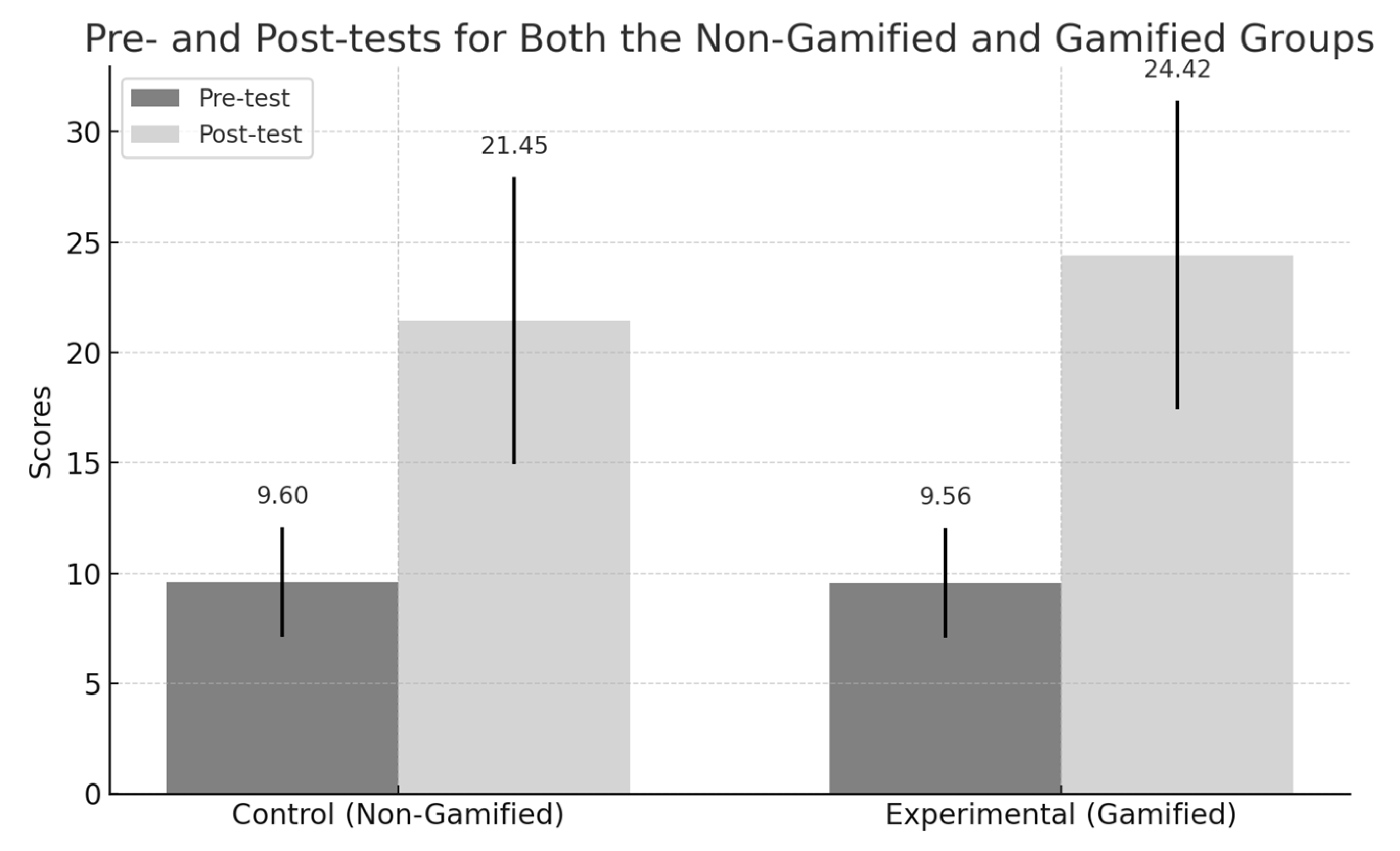

| Group | n | Pre-Test (SD) | Post-Test (SD) | Mean of Post-Pre (SD) | Mean Difference | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | 50 (M = 21, F = 29) | 9.56 (3.16) | 24.42 (7.40) | 14.86 (8.35) | −3.005 | 0.039 * | 0.423 |

| Control Group | 48 (M = 22, F = 26) | 9.60 (3.11) | 21.45 (6.34) | 11.85 (5.50) |

| GEQ Questionnaires | Group | n | Mean (SD) | Mean Difference | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersion | Experimental | 50 | 3.86 (0.88) | −0.380 | 0.042 * | 0.417 |

| Control | 48 | 3.47 (0.04) | ||||

| Flow | Experimental | 50 | 3.78 (0.86) | −0.425 | 0.039 * | 0.422 |

| Control | 48 | 3.35 (1.13) | ||||

| Social Interaction | Experimental | 50 | 3.76 (1.02) | −0.447 | 0.030 * | 0.444 |

| Control | 48 | 3.31 (0.99) | ||||

| Enjoyment | Experimental | 50 | 3.86 (0.72) | −0.422 | 0.033 * | 0.437 |

| Control | 48 | 3.43 (1.16) |

| Group | n | Total Number of Rounds Played | Average Rounds Played per Player | Total Game Score | Average Game Score per Player |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 50 | 243 | 4.86 | 175,948 | 3518.96 |

| Control | 48 | 132 | 3.20 | 125,952 | 2624.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khanchai, S.; Worragin, P.; Ariya, P.; Intawong, K.; Puritat, K. Toward Sustainable Digital Literacy: A Comparative Study of Gamified and Non-Gamified Digital Board Games in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080966

Khanchai S, Worragin P, Ariya P, Intawong K, Puritat K. Toward Sustainable Digital Literacy: A Comparative Study of Gamified and Non-Gamified Digital Board Games in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080966

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhanchai, Songpon, Perasuk Worragin, Pakinee Ariya, Kannikar Intawong, and Kitti Puritat. 2025. "Toward Sustainable Digital Literacy: A Comparative Study of Gamified and Non-Gamified Digital Board Games in Higher Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080966

APA StyleKhanchai, S., Worragin, P., Ariya, P., Intawong, K., & Puritat, K. (2025). Toward Sustainable Digital Literacy: A Comparative Study of Gamified and Non-Gamified Digital Board Games in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 15(8), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080966