1. Introduction

Fostering professional identity among students in the field of education significantly influences their quality and effectiveness as professionals in pedagogy and social pedagogy. However, the construction of an educator’s identity begins well before university-level training. It is rooted in experiences, relationships, and role models both within and beyond formal education (

Bonal et al., 2005;

González González, 2014;

Nasir & Hand, 2008;

Blasco-Serrano et al., 2023), in values acquired across multiple learning environments (

Barron, 2006), and in reflective engagement with one’s own educational journey. These environments are also shaped by intersecting social, cultural, and political contexts that influence students’ trajectories and their relationships with educational institutions (

Vain, 2022;

Cárcamo-Hernández, 2023). All these factors impact academic success, socio-educational integration, peer relationships (

Mateos & Núñez, 2011), and the motivations behind choosing a particular educational and professional path (

Llanes Ordóñez et al., 2021).

Barron’s (

2006) model of learning ecologies challenges the traditional focus on school as the sole learning space and raises important questions about the interdependencies among various learning environments. The way these environments are selected and combined helps explain the development of interest and competence. The ecological learning model theorizes how (where, how, through whom) individuals build their skills and knowledge, and how this process contributes to identity formation. Among these elements, school emerges as a privileged context, and peer relationships play a central role. Additionally, the concept of ideational resources—which includes self-perceptions, one’s place in the world, and what one values (

Nasir & Hand, 2008;

Tierney, 2020)—is directly linked to how students conceptualize “being a good educator” and their motivation to pursue a career in education.

This process of reflection and self-dialogue is embedded in the competencies outlined in the curricula of education degree programs of two Spanish Universities. In Pedagogy and Social Education degrees, the course Anthropology of Education is assigned general competencies such as the ability to critically evaluate one’s own learning processes; to develop an innovative, critical, and personal approach to concepts and techniques relevant to the field; and to address various aspects of the subject from a global and systematic perspective.

A key factor in the development of a professional identity as an educator is the need to deconstruct, reconstruct, and establish one’s own teaching and learning processes (

Jové, 2014). This requires a commitment to reflection and self-dialogue, as well as engagement with the educational task (

Blanchard & Fernandes, 2021). According to these authors, the construction of the educator identity during initial training enables the students to achieve the following:

“…recall their experiences as learners through activities that bring to the present both positive and negative experiences—and the reasons or factors that influenced them—in relation to their learning and interpersonal relationships, engaging in metacognitive reflection and recognizing the context in which these experiences occurred”

(p. 5)

These processes of personal reflection and dialogue are explicitly included in the competencies assigned to the Anthropology of Education course in the curricula of pedagogy and social education degrees at Spanish universities.

To support the development of these competencies through reflection on individual educational experiences, a learning activity was proposed to first-year pedagogy students at the University of Balearic Islands and second-year social education students at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. The activity involved writing an educational autoethnography within the framework of the Anthropology of Education course.

This pedagogical activity also had an exploratory aim: to investigate the factors that influenced students’ decisions regarding their educational and professional paths. The participants shared several characteristics: (1) they had chosen to pursue education-related studies (in this case, with a social rather than teaching focus); (2) they shared a common educational background shaped by the same school system (defined by legislation, policies, values, and practices); (3) they belonged to the same generational and cultural cohort; and (4) they had developed strategies that enabled them to successfully navigate higher education.

Based on these shared elements, this study posed the following research questions: What factors influenced their interest in this educational path? How did their experiences across different stages of the education system shape this decision? What impact did the various educational agents they encountered throughout their lives have on their trajectories?

Llanes Ordóñez et al. (

2021) have argued that students’ decisions to pursue higher education in the field of Education are primarily motivated by intrinsic factors—such as a strong sense of vocation, the intrinsic pleasure of learning, the desire to develop personal competencies and attitudes, and a commitment to social improvement and the well-being of their immediate communities. However, as

Vain (

2022) emphasized, educational trajectories are shaped by a complex interplay of processes, relationships, and contextual factors. Understanding how students make academic and professional choices therefore requires a biographical approach that considers their lived experiences (

Vain, 2022;

Carmona-Legaz & Sánchez-Marín, 2024). In this context, students’ interpretations of their own schooling experiences provide valuable insights into the impact of educational practices on their learning strategies and their decision to pursue a career in pedagogy or social education. These reflections also shed light on the broader dynamics that influence the educational process—such as sociability, inequality, social order, adaptation, and socialization (

Pérez et al., 2022). Moreover, this reflective exercise enables an assessment of the formal education system’s capacity to foster role models and generate meaningful experiences that inspire students to engage in the field of education.

Consequently, the aim of this study is to explore the elements that influence students’ motivations in choosing a professional pathway in the fields of pedagogy and social pedagogy. The analysis is structured around the four learning ecologies proposed by

Barron (

2006): family upbringing, formal schooling, non-formal/informal education, and interpersonal relationships. By analysing students’ narratives, we seek to understand the meaning and value they assign to these learning environments throughout their educational development. In doing so, we drew on

Vain’s (

2022) perspective, which advocates for placing the individual at the centre of the analysis to understand how academic education is shaped by students’ subjective experiences.

Autoethnography as a Method for Learning and Inquiry

Ethnography is one of the core methodological approaches addressed in the course. Autoethnography, in particular, combines research and narrative writing, drawing on thick description (

Geertz, 1996) and the systematic analysis of personal experiences as a means of understanding one’s own cultural background (

Brockmeier, 2000;

Ellis & Bochner, 2000,

2006;

Ellis, 2004;

Holman, 2005). It involves reinterpreting lived experiences to shed light on the broader contexts in which they occurred (

Blanco, 2012).

In the educational field, autoethnography serves as a powerful tool for raising students’ awareness of their own learning ecologies and the factors that shape them (

Martínez-Rodríguez & Benítez-Corona, 2020). It supports the identification of personal strengths and limitations (

Serrano-Miguel, 2022) and contributes to the development of a professional identity as future educators (

Barron, 2006). As an initial step in reflective practice, it enables students to interpret their educational experiences from an external perspective, situating them within both a cultural and contextual framework and an anthropological theoretical lens.

According to

Guerrero (

2019), this analytical process is particularly relevant in social and educational contexts, as it fosters critical reflection, introspection, empathy, and vulnerability. These capacities are essential for developing culturally responsive, socially engaged, and ethically grounded educational practices aimed at improving the lives of others.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Informants

This study is based on a discourse analysis of 138 autoethnographic narratives written by students enrolled in Pedagogy and Social Education programs at the University of Balearic Islands and the Autonomous University of Barcelona, following informed consent and with the approval of the University’s Ethics Committee. Of the 138 participants, 79 were first-year Pedagogy students (representing 45.7% of those enrolled) and 59 were second-year Social Education students (75% of the cohort). The fact that the Pedagogy students were in their first year at one university, while the Social Education students were in their second year at another influenced the narratives, as the latter group demonstrated greater maturity and academic experience. Both degree programs have a high proportion of female students, which is reflected in the sample: there were only eight male students in the Pedagogy group and three in the Social Education group.

The participants came from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds, although the sample is relatively homogeneous in terms of ethnic and cultural diversity, with a low percentage of students of foreign origin. Those with migrant backgrounds were primarily from Latin America, North Africa, and, in one case, Pakistan. However, most were either born in the region or arrived during early childhood and were educated within the Spanish and regional school systems.

In the Autonomous University of Barcelona sample, 75% of students accessed university through the traditional academic track (High School Diploma), while the remaining 25% entered via higher vocational training programs—mainly in Social Integration or Early Childhood Education—or through alternative pathways. In the second institution University of Balearic Islands], approximately 80% of students entered from High School Diploma, and 20% from vocational or other routes.

2.2. Procedure

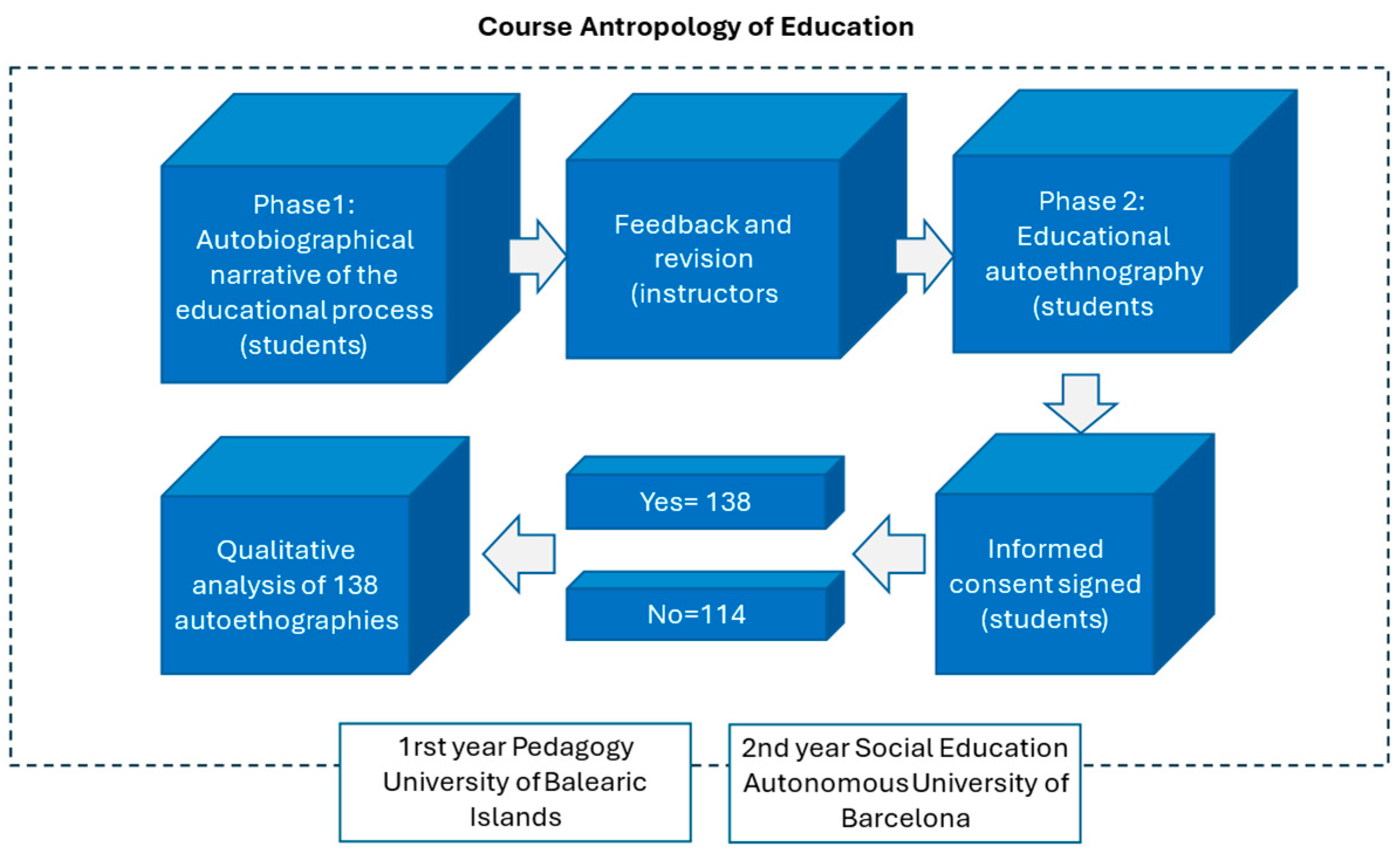

Figure 1 describes the procedure followed in this study.

Anthropology of Education is a compulsory course in both degree programs examined and is delivered through a shared syllabus. As part of the course requirements, students were assigned an educational autoethnography, following the methodological framework outlined by

Ellis and Bochner (

2000,

2006) and

Ellis (

2004). The assignment was structured in two phases.

In the first phase, students—having already been introduced to ethnographic methods and key concepts in educational anthropology (such as culture, enculturation, acculturation, identity, diversity, inequality, and cultural transmission)—were asked to write an initial autobiographical narrative recounting their educational experiences, both within and beyond formal schooling. These narratives were reviewed by the lecturers and returned with formative feedback for improvement.

In the second phase, students were invited to critically reflect on and analyse their narratives, linking their personal experiences to broader cultural factors that had shaped their educational decisions and interpretations of reality. Most students focused on connecting their experiences to key cultural themes explored in the course, such as coeducation, gender equality, value and cultural transmission, educational agents and mechanisms of enculturation, social and family capital, sociability, educational inequalities, and various forms of discrimination (xenophobia, racism, classism, gender-based discrimination, ableism, Islamophobia, anti-Roma bias, among others.). This second, more analytically rich narrative formed the basis for the present study.

2.3. Data Analysis

The qualitative analysis of the narratives was conducted using MAXQDA 22, employing a mixed coding strategy. Predefined categories were established based on the four learning ecologies, while subcategories emerged through open coding. To ensure participant anonymity, all personal names referenced in the narratives were replaced with pseudonyms.

3. Results

The analysis provides insight into the types of learning environments that have been most meaningful for students, the strategies they have employed, and the resources they have accessed in shaping their educational and professional trajectories within the field of education.

The development of a professional identity is influenced by four main learning environments (

Blanchard & Fernandes, 2021): individuals who serve as positive or negative role models; the experiences that inform identity construction and the relationships formed through them, along with students’ conscious engagement with both; and the reflective processes and decisions that emerge from these reflections, as articulated in students’ narratives. To identify these factors, the analysis was organized around four domains: the family, non-formal education, formal schooling, and peer groups.

3.1. The Family

The family constitutes the foundational context—or “origin”—from which individuals derive their core identity and values. Students frequently identify the family as the primary source of the elements that have shaped their sense of self and guided their educational decisions. They recount a range of familial and social experiences that have marked significant turning points in their lives, both positively and negatively. These include changes in family structure, experiences of abuse, residential relocations, migration processes, family conflicts, bereavement, health challenges, economic hardship, and religious influences. Such factors shape the processes of value transmission, identity formation, and personality development.

The intersection between family and school emerges at the very onset of formal education. Narratives about the beginning of schooling often centre on a key family decision: the choice of an educational institution. This choice is influenced by several factors, including parental beliefs about caregiving responsibilities, the cultural context, the family’s socio-educational background, ideological orientations, and expectations regarding the desired educational model. Additionally, pragmatic considerations—such as the school’s proximity, availability of services like school meals, and alignment with the family’s daily routines—also play a significant role.

“I was enrolled in this school because (…) my family was religious (…). They looked down a bit on public schools because they believed only people without values went there.”

(María, 1st year Pedagogy)

The intersection between family and school extends beyond the initial decision of school enrolment and continues throughout students’ academic journey. It is manifested through various forms of family involvement: family support, the value the family places on education, and the mobilization of family capital—understood as the strategies and resources families employ to foster academic success. Furthermore, parents’ expectations and encouragement also play a role in sustaining students’ motivation in their educational process.

Parental engagement in their children’s education, along with their sustained efforts and support, mark the beginning of the narratives, with mothers often playing a central role. While social class undeniably influences educational trajectories, the completion of secondary education and access to higher education should not be viewed as rigidly determined by class-based habits. Rather, these outcomes are shaped by parents’ support and expectations placed on students through their trajectories:

“(…) [my mother] always made me aware that studying would make the future easier and that I would have a better quality of life with a university degree.”

(Ona, 1st year Pedagogy)

3.2. Non-Formal Learning Spaces

Non-formal education—including leisure activities, sports, and civic engagement, among others—constitutes a privileged ecology for learning and the acquisition of values. Regardless of specific activities, these experiences are consistently associated with the values that students have internalized, and which have contributed, consciously or unconsciously, to the construction of their personal, social, and professional identity.

Non-formal learning is also closely linked with the educational expectations held by families. It is often parents who encourage participation in extracurricular activities that complement formal education and expand social networks. As with school experiences, these extracurricular involvements occur within a social framework shaped by class, race, and gender inequalities (

Dubet & Martuccelli, 1998), a reality that students themselves acknowledge in their narratives:

“I never had the opportunity to go to summer camps, or join a youth club or group, so school was the only place where I could meet people my age with similar interests.”

(Andrea, 2nd year Social Education)

Structured leisure activities and non-formal learning spaces—such as youth associations, scouting groups, and sports clubs—are widely regarded as opportunities to acquire values and skills: learning social roles, participation, solidarity, commitment, social and political awareness, teamwork, passion, perseverance, acceptance of diversity, tolerance, empathy, equality, respect, cooperation, and mutual support. These forms of learning are often contrasted with those acquired in school. Students’ narratives tend to distinguish between the two learning environments, often portraying school—as a stereotyped concept—as a rigid and hierarchical space focused on normative knowledge and practices, where relationships are unequal—and therefore discriminatory—and, in some accounts, where competitiveness is encouraged. In contrast, non-formal and informal learning spaces are generally described as ‘free, open, and designed to foster personal growth (physical, social, emotional, and artistic)’, places where ‘no one judges you and everyone is friends’, where social relationships are ‘healthier and more authentic’ and where students can belong to a group, form lifelong friends and share meaningful experiences’. These are also described as spaces where one learns ‘to live, to coexist with others’, ‘to value others’, ‘to value oneself’, and above all, as ‘spaces for disconnection’.

Nevertheless, school—particularly primary education—is also recognized as a space for developing essential social and professional skills, such as critical thinking, decision-making, and teamwork, and values like discipline, perseverance, acceptance of diversity, equality, responsibility, and solidarity:

“[School] helped me develop critical thinking, decision-making, and discussion skills through cooperative group work, and instilled values like responsibility, solidarity, and respect for others and the environment.”

(Clara, 2nd year Social Education)

For many students in Social Education, the non-formal learning spaces play a decisive role in shaping their professional orientation. Their experiences are often perceived as a “continuation” of a socially engaged approach to education. Students’ non-formal learning has contributed to the formation of a professional identity that seeks to bridge formal and non-formal education spaces. Grounded in holistic educational approaches (

Díaz de Rada, 2013;

Freire, 1970), this identity integrates academic knowledge with students’ lived social realities.

3.3. Formal Education and School Environments

Students’ experiences within educational institutions are structured around a set of elements that freely emerge in their narratives. Several of these elements reflect a dichotomous evaluation—either positive or negative—across specific domains such as educational role models, institutional functioning and management, and educational transitions.

3.3.1. Educational Role Models

Positive relationships with educational professionals—such as teachers, counsellors, and tutors—are closely linked to the support students receive in challenging situations and, more importantly, to the role these figures play in their personal development. Research has shown a strong correlation between teacher support and students’ academic performance (

Fernández-Lasarte et al., 2019), a connection that is also reflected in the autoethnographic narratives analyzed.

“[The teacher] helped me understand that I wasn’t inferior to others, that I was capable—even if I sometimes needed more time (…). My grades and motivation to study began to improve.”

(Aina, 2nd year, Social Education)

These role models are clearly referenced in students’ narratives and play a significant role in shaping their educational trajectories. While many express a desire to ‘be like’ certain teachers, others refer to ‘not wanting to be like’ educators perceived as negative models—due to their lack of support, ineffective teaching methods, or behaviours and practices that contradict students’ ideals of what it means to be a ‘good teacher’.

3.3.2. Institutional Functioning and Management

The functioning and management of educational institutions are closely intertwined with the academic and emotional support they provide to students. These dimensions significantly shape students’ perceptions of their schools, particularly in relation to how institutions respond to critical issues such as bullying, interpersonal conflicts, support for students with special educational needs, and academic and vocational guidance, among others. Likewise, teaching methods are evaluated in terms of their effectiveness and academic relevance—‘usefulness’ in their own words—often based on students’ direct experiences with educators, both positive and negative.

In contrast, the school’s ideological framework is subject to critical scrutiny, based on their alignment—or lack thereof—with students’ and/or their families’ own values and belief systems. As

Pérez et al. (

2022) observed, there is a notable relationship between students’ perceptions and expectations of what constitutes a good teacher or school and the principles underpinning the educational system. In this context, it is particularly relevant to examine the tensions between students’ educational ideals and the practices they encountered.

Students’ assessments of schools—as spaces where pedagogical, educational, and social principles established by law are put into practice—are frequently cited as a catalyst for pursuing a career in social education or working within educational settings. These decisions are framed either as an act of emulation, in response to positive school experiences, or as acts of resistance, in reaction to negative ones. In the former case, the presence of a significant role model who embodies supportive and inclusive educational practices and attitudes is often decisive:

“I had a teacher who really marked me (…), when I finished primary school, she told me: ‘Don’t worry, I’m a teacher and I have dyslexia. Maybe I need five hours to study while my friends need one, but here I am, living my dream.’ That made me realize I didn’t have to give up—she helped me move forward.”

(Claudia, 1st year, Pedagogy)

Conversely, rejection is often directed at both institutional policies and the school’s internal dynamics, especially regarding the lack of support for students with diverse educational needs.

One of the most recurrent criticisms in students’ narratives concerns the school’s role in managing coexistence, particularly in cases of bullying and violence. These accounts frequently highlight a perceived ‘lack of institucional action or concern’, with resolution often achieved through the support of trusted adults or peers.

Among students from non-dominant ethnic, racial, or culturally minoritized backgrounds, negative perceptions of the school are often attributed to a lack of intercultural sensitivity or to institutional racism, which directly undermine their motivation. In some cases, inadequate management of coexistence is interpreted through lenses of class, ethnicity, or gender.

3.3.3. Educational Transitions

Educational transitions represent a critical and transformative moments in students’ trajectories. While the transition from early childhood education to primary school is generally experienced as a natural progression, the shift from primary to secondary education—especially when it involves changing institutions—is often described as either a traumatic rupture or a liberating opportunity. These transitions mark a ‘

new beginning’ in which students renegotiate social relationships, adapt to new academic practices, and develop new ways of engaging with learning. In some cases, they also serve as opportunities for identity reconstruction (

Tierney, 2020).

“Starting secondary school was difficult. Coming from such a small school to what felt like a huge high school was overwhelming for me.”

(Aina, 2nd year, Social Education)

Finally, the imminence of the end of compulsory education and the uncertainty surrounding post-secondary pathways compel students to reflect critically on their future roles, aspirations, and educational choices.

3.4. Peer Groups and Social Relationships in School Contexts

Most students structure their educational narratives around their social relationships—both with peers and with adults. These interactions play a fundamental role in the construction of personal identity and character, as well as in their learning process and value acquisition (

Estévez et al., 2009). School emerges as a dual space of learning. On the one hand, it is perceived instrumentally as an obligatory stage in life that enables progression through the educational system and, depending on the level of success achieved and the strategies employed, enables access to the desired professional futures. On the other hand, school is also experienced as a space of intensive learning, not only of academic content and competencies, but also of social skills and relational capacities that shape students’ social environment. These two dimensions are contrasted in students’ narratives, with emotional and relational learning (e.g., freedom, affection, coexistence, friendship) being valued as more authentic and personally transformative than formal academic knowledge.

Peer relationships within the school environment are consistently highlighted as a source of learning. They are described as both supportive and challenging with inclusion and exclusion dynamics having a central role in students’ sense of belonging. The need to ‘fit in’ with peers is a recurring theme in their discourse, particularly during educational transitions. These transitions—structurally defined by the education system—are described as critical moments of identity negotiation, involving shifts in social roles and relational dynamics among peers.

Students describe the learning that comes with role changes and new ways of relating, which require them to constantly reposition themselves within their social groups. Transitions from one educational stage to another are seen as modern rites of passage and require continuous repositioning within evolving peer groups.

“The transition from one stage to another marked a great improvement in my grades, largely because the environment was different and I felt loved and supported by those around me.”

(Ona, 1st year, Pedagogy)

Diversity is frequently described as a positive and enriching factor, valued for its socializing dimension and its influence on peer inclusion or exclusion and identity formation. Also, gender emerges as a dimension of socialization within peer interactions. Through these relationships students learn, internalize, and resist socially assigned gender roles. Notably, many students express critical reflections on gender inequality, both within the hidden curriculum—whether experienced directly or observed—and in their broader social environments. These narratives reveal how hegemonic gender norms affect students’ experiences of identity development, mostly reflecting on how they affected their gender construction.

4. Discussion and Conclusions: Reflections from Autoethnographic Narratives

The analysis of students’ school narratives offers a nuanced understanding of how they progressively construct the image and ideal of the educator they aspire to become. Their accounts reveal two contrasting entry points into the profession: on the one hand, a lack of familiarity or a stereotyped perception of the profession; on the other, a strong sense of conviction. This conviction often emerges from a desire either to emulate positive role models or to distance themselves from negative ones.

Secondary school guidance plays a significant role in shaping students’ perceptions of institutional support, extending beyond academic advice to encompass attention to diversity, personal counselling, and emotional accompaniment. While acknowledging the influence of class-based biases in career guidance and their impact on students’ employment-related decisions (

Oller et al., 2021;

Vain, 2022), our findings highlight the multiplicity of actors and the complexity of decision-making processes involved in educational choice.

Crucially, students’ motivation to pursue education-related degrees is anchored in the values they have internalized across diverse learning ecologies. Their narratives consistently emphasize respect for diversity, critical awareness of prejudice and stereotypes, and a strong ethical commitment to social justice. In some cases, this awareness is catalysed by self-reflection on their own past inaction in the face of discrimination or bullying. Education is thus conceived of not merely as a professional path, but as a vehicle for social transformation—resonating with the principles of social education as ‘an initiative aimed at promoting and energizing a society that educates and an education that integrates, contributing to the prevention and resolution of social difficulties and conflicts’ (

Ortega Esteban, 2005, p. 111).

The desire to help others emerges as a central motivational axis, often articulated through narratives of gratitude and reciprocity for support received, or through formative experiences in volunteering, social activism, or non-formal education (such as scouting, youth clubs). In some instances, this vocational drive is rooted in negative personal experiences—motivated by the aspiration to prevent others from enduring similar harm—and accompanied by critical reflections on institutional shortcomings. A hopeful and affirmative outlook on life, and the desire to share it with others, is also framed as a core pedagogical value.

Bonal et al. (

2005) identified a range of individual and collective attitudes that students adopt toward school and other social spaces (e.g., family, leisure), shaped by the organizational logics and normative strategies embedded in each. According to these authors, academic success is contingent upon students’ degree of alignment with school culture and their ability to navigate its learning demands. The autoethnographic narratives examined here reflect a dynamic interplay between cultural spaces. Students demonstrate a capacity to differentiate between learning ecologies, to articulate the knowledge and values acquired in each, and to assess their relative influence on their decision to pursue a career in education. Even in cases where there is a pronounced dissonance between family/social culture and school culture, this gap does not appear to be determining. However, this affirmation should be taken with care, since our sample does not have many students of minority groups, who might have dropped out or taken other degrees.

Students’ reflections on their own trajectories as learners—and the relationships they have cultivated with family, support agents, school, teachers, and peers—contribute to shaping their educational and professional pathways. These trajectories are not perceived as linear or predetermined, but rather as a part of an ongoing, generationally situated process in which change—in career, of training, of life—is normalized. This orientation fosters a relatively homogeneous pattern of adherence to the normative structure of the educational system and a naturalization of certain experiences as students. Yet this conformity is not devoid of critical consciousness; indeed, it is often this critical awareness that fuels students’ desire to enact change from within the system.

The collective analysis of students’ autoethnographic narratives enables the articulation of diverse individual and collective experiences within the shared framework of the educational system. It illuminates how young people from the same generational cohort construct their professional projects and educational trajectories. Simultaneously, it offers a critical lens on the educational system they have inhabited. Through their accounts of challenges encountered in school, students expose the inertia of a system in transition—from a rigid model (in terms of methods, management of coexistence, institutional practices, etc.) to a more inclusive paradigm oriented toward the needs of diverse learners, grounded in support, teacher–student relationships and active methodologies. It is this latter model with which they strongly identify as future educators—though their identification is marked by a reformist rather than a revolutionary stance and by an as-yet undefined vision of the professional relationship they wish to cultivate with schools, students, and the broader educational system.

Critical reflection on their own educational experiences contributes to delineating the contours of future social education and pedagogy professional identities. Moreover, autoethnographic narratives have the potential to transform personal experiences into shared, socially meaningful knowledge, thereby inspiring cultural change (

Adams & Holman Jones, 2011). These narratives and their analysis can inform and enrich the educational discourse by offering alternative analytical frameworks that move beyond institutional or academic perspectives (

Bossle et al., 2014), and instead, highlight the lived experiences of students within the school system.

The analysis of these narratives reveals the motivational foundations underpinning students’ educational choices and also provides ground for further inquiry into how young people respond to the structures and dynamics of schooling. It is important, however, to acknowledge the situated nature of these narratives: they were produced within the context of a university course, subject to assessment and guided by specific criteria. Students’ interpretations of what they believe is expected by the instructor may introduce a degree of performativity or bias that must be considered in the analysis. Nonetheless, as

Vain (

2022) argues, these narratives open avenues for future research that centres students’ voices in the study of how educational and professional trajectories are constructed.

To conclude, our analysis of students’ autoethnographic accounts suggest that their motivation to pursue education-related degrees is not solely driven by academic interests. Rather, it is shaped by a strong ethical and emotional commitment grounded in their lived experiences that play a significant role in shaping their vocational orientation. Non-formal learning environments emerge as particularly influential, though access to them is not equally distributed, raising questions about equity. These findings carry implications for future-educator training programmes.

First, we believe that they underscore the importance of integrating structured opportunities for students to reflect on their own educational biographies. As

Acker (

1999) noted, biographical reflection is not merely anecdotal but constitutes a valuable source of pedagogical insight. Encouraging future educators to explore how their personal histories influence their beliefs and practices can foster deeper self-awareness and a more critical stance toward the educational system. Creating collaborative spaces for this kind of reflection would enrich the learning experience and support the development of a more grounded professional identity.

In addition, the central role attributed to extracurricular and non-formal learning spaces challenges the notion that these are peripheral to formal education. Instead, they should be recognized as essential components of holistic educational development and be critically examined within the teacher training programmes—examining contribution, exploring ways to strengthen collaboration, and ensuring equitable access. We consider that this recognition should extend beyond social education curriculums, where it is currently acknowledged, to include the teacher training curriculums.

Finally, the findings reinforce the need to train educators who are critically reflective, aware of their role as agents of change.