Abstract

Technology is essential in higher education, yet disparities in access disproportionately affect first-generation college students. This study examines how technology access and financial stress impact academic performance for first-generation (FGCS) and continuing-generation college students (CGCS). Students (N = 430) were asked to reflect on their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly their technology access and financial stress. Results showed that FGCS reported significantly lower technology access and higher levels of financial stress than CGCS. Greater technology access was a significant positive predictor of academic performance for FGCS but not CGCS. However, this effect diminished when financial stress was added to the regression model. Moderation analysis showed that financial stress significantly moderated the relation between technology access and academic performance. This suggests that under high financial stress, technology access becomes a critical resource for academic performance.

1. Introduction

In today’s digital age, both access to and proficiency with technology are crucial drivers of academic success, significantly enhancing students’ learning processes and outcomes (Wekerle et al., 2020). However, access to these tools and the necessary digital skills are not evenly distributed, leading to notable disparities in academic performance (Gonzales et al., 2020). These disparities are especially pronounced among students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and students of color (Barber et al., 2021; Fischer, 2020). First-generation college students, in particular, often lag behind their peers in digital proficiency, which can further hinder their academic success (Deng & Yang, 2021). While existing research has increasingly underscored the importance of technology in education (Akram et al., 2021; Huffman & Huffman, 2012), there is a lack of exploration into how this access—or lack thereof—interacts with other critical factors, such as financial stress, to influence academic outcomes. Financial stress and technological barriers are commonly treated as separate issues rather than being examined for their combined impact. In contrast, this study examines the relation between technology access, financial stress, and academic performance, highlighting the challenges faced by first-generation college students compared to continuing-generation college students.

In recent decades, the proportion of the U.S. population earning a bachelor’s degree has grown significantly, with the percentage of adults aged 25 and older holding a degree increasing from 21% in 1990 to 33% in 2015 (Goldman et al., 2020). Despite this progress, generational status continues to influence students’ access to resources, preparedness, and their ability to navigate college life. First-generation college students (FGCS), those whose parents did not complete a four-year college degree, often face more challenges than continuing generation college students (CGCS), whose parents did complete such a degree (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017; Covarrubias et al., 2019; Galina, 2016; Irlbeck et al., 2014). These challenges contribute to higher dropout rates among FGCS compared to their peers (Cataldi et al., 2018; Goldman et al., 2020).

FGCS, who are more likely to come from low-income and minority backgrounds (Amirkhan et al., 2023; Deng & Yang, 2021; Galina, 2016), and encounter considerable difficulties in both their academic (Allan et al., 2016; Cataldi et al., 2018; Goldman et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2020) and social experiences (Covarrubias et al., 2019; Galina, 2016; Irlbeck et al., 2014). Many are responsible for providing emotional support, language brokering, financial assistance, physical care, and sibling caretaking for their families (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017; Covarrubias et al., 2019). They struggle with transitioning to university life due to a lack of familiarity with the academic environment and limited support systems (Galina, 2016). Parents of FGCS, despite being supportive (Irlbeck et al., 2014), may not fully understand or be able to provide the academic support needed (Galina, 2016; Irlbeck et al., 2014). These factors contribute to lower grades (Allan et al., 2016; Amirkhan et al., 2023; Baker & Montalto, 2019; Phillips et al., 2020), lower critical-thinking scores, reduced contact with faculty, and less time for academic tasks (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017). This ultimately compromises their academic and social integration on campus (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017; Phillips et al., 2020). Although focusing more on coursework can lead to higher GPAs and math grades (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017), balancing the various demands remains challenging.

The difficulties faced by FGCS were further amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic forced an unprecedented transformation in education, prompting a rapid shift from traditional classroom settings to emergency remote education (Bozkurt et al., 2022). While many students indicated increased interest in remote learning due to greater access to courses and scheduling flexibility, this positive experience was far from universal (Barber et al., 2021). Remote learning’s dependence on technology exposed stark disparities in access and usage, particularly affecting students from lower-income and first-generation backgrounds (Barber et al., 2021; Fischer, 2020).

FGCS faced multiple challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. They had to return to their multi-generational homes, where they often lacked reliable internet and access to necessary academic tools like laptops (Fischer, 2020). In addition to the shortage of resources, many FGCS needed to take on greater caregiving responsibilities. This includes helping siblings with remote learning, all the while managing with lower household incomes and significant COVID-19-related income losses (Barber et al., 2021; Deng & Yang, 2021). These students were nearly twice as likely to worry about affording their education for Fall 2020 and were more likely to experience food and housing insecurity (Soria et al., 2020), financial stress (Wilcox et al., 2022), unsafe living conditions, and mental health struggles (Soria et al., 2020). The shift to online learning worsened the academic experiences of FGCS. They often lacked adequate study spaces and technology, making it harder to adapt to virtual instruction and attend scheduled class times (Deng & Yang, 2021; Soria et al., 2020).

The pandemic not only exacerbated existing disparities in technology access but also highlighted how these inequities hindered academic success, particularly for FGCS. For example, FGCS students who came from low-income households might have lacked access to reliable high-speed internet or devices necessary for participating in virtual coursework. For example, they might have had to share a single laptop among family members or attend virtual classes from their phones. This hindered their ability to engage fully with learning materials (Means & Neisler, 2021). The digital divide disproportionately affected traditionally marginalized groups, including FGCS, intersecting with race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. This ultimately impacted their ability to succeed academically (Whitley et al., 2018).

The present study is grounded in Van Dijk’s (2012) Resources and Appropriation Theory and Bronfenbrenner’s (1988) Ecological Systems Theory, later refined as the Bioecological Model of Human Development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Van Dijk’s Resources and Appropriation Theory highlights how structural inequalities, such as generational status, can create unequal access to digital technologies (Van Dijk, 2012). This issue was further exacerbated during the pandemic, as FGCS faced heightened financial strain, inadequate study spaces, and limited access to technology (Soria et al., 2020; Barber et al., 2021). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model expands this lens by examining how other layers of a student’s environment, such as financial stress, interact with access to technology to influence academic outcomes. FGCS not only faced technological barriers but were also expected to take on additional responsibilities at home during the pandemic, such as caregiving and financial support (Covarrubias et al., 2019; Deng & Yang, 2021). These responsibilities, combined with systemic inequalities in access to digital resources, highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of the digital divide (Van Dijk, 2017).

While most universities equip students with a variety of technological resources to support their academic success, financial stress might be a barrier. Specifically, it could limit the benefits of technology access, making it less effective in closing achievement gaps. This study examines how technology access and financial stress impact academic performance. It goes beyond basic comparisons between FGCS and CGCS in technology access and financial stress—it explores how technology access and financial stress interact to influence college students’ academic performance. Specifically, we investigate whether financial stress moderates the relationship between technology access and academic outcomes. Technology access alone might not be enough for a high academic performance. Students need to have the time, stability, and motivation to use technology meaningfully (Van Dijk, 2012), especially for academic purposes. High financial stress could interfere with this by creating competing demands. This might reduce students’ capacity to benefit academically from technology access. By exploring this, our findings not only contribute to the research literature on barriers in higher education but also inform university policies to ensure that support programs are not only accessible but truly impactful in mitigating academic disparities. This is especially important since virtual learning environments have become more prominent during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This research specifically focuses on the self-reported academic outcomes of FGCS and CGCS in Fall 2020, after the shift to online learning in Spring 2019. It addresses the following research questions:

- (1)

- What are the differences in technology access and financial stress between FGCS and CGCS?

- (2)

- How do technology access and students’ reported levels of financial stress relate to academic performance for both FGCS and CGCS?

- (3)

- Do technology access and financial stress interact to influence college students’ academic outcomes?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the researchers’ academic institution as exempt research (Protocol Number: 531, Version 9). A total of 430 students (126 FGCS and 304 CGCS) participated in the study. All participants were required to be registered for courses at the university during the Fall 2020 semester. Females represented 64%, males represented 32%, and non-binary or other identifications represented 4.5%. The overall average age among all students was 20.9 (SD = 2.5), with a mean age of 21.39 (SD = 2.71) for FGCS, and 20.58 (SD = 2.30) for CGCS. The sample was racially and ethnically diverse, mirroring the demographic profile of the mid-sized public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States where data collection took place (see Table 1 for all demographics). Consistent with existing research, FGCS came from families with significantly lower income levels compared to CGCS. Nearly half of FGCS said their family earned less than $50,000 a year. CGCS tended to report higher incomes. The largest group of CGCS (22%) reported family incomes above $125,000, and 27% reported incomes between $100,000 and $125,000.

Table 1.

Demographics Characteristics of FGCS and CGCS.

2.2. Measures

The study used an online Qualtrics questionnaire, where participants provided information regarding their attitudes and behaviors during the prior Fall 2020 semester. Several key measures were included in the questionnaire, such as Online Student Engagement, with 19 items (OSE; Dixson, 2015), the Academic Motivation Scale, with 28 items (AMS-C28; Vallerand et al., 1989), and various indicators of Technology Usage and Challenges (12 items), Financial Stress (6 items), Grade Point Average (GPA), Support Networks (including friends with 8 items, family with 8 items, professors with 10 items, and home environment with 7 items), School Support (7 items), and Mental Health (8 items).

For the purposes of this study, the focus was on technology-related challenges, financial stress, and academic performance as measured by self-reported GPA. The questions asked about participants’ technology access and the financial stress experienced. For instance, participants were asked how often (7-point Likert scale) they had to share devices such as laptops, tablets, or phones with others since the onset of COVID-19, with responses ranging from “Never” to “Always.” The participants were also asked to indicate their level of agreement with several statements related to their experiences during the pandemic using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” For example, they were asked whether they had sufficient access to the necessary technology for their online courses and whether technology difficulties caused them to be late or miss classes. In terms of financial stress, participants were asked whether they felt more stressed about their financial situation due to COVID-19. They also indicated if their financial stress levels had increased compared to pre-pandemic times.

The technology access scale was developed for this study to capture students’ experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Items were adapted from existing research on digital access and student engagement and aligned with themes identified in pandemic-era education literature (Means & Neisler, 2021; Radu et al., 2020). Five items were selected to reflect both resource access and technological obstacles. There were no missing responses for any items on this scale. The variable was computed by summing the following five items: “In general, I would say I am good with technology”, “I have sufficient access to the tech”, “I have a stable Wi-Fi connection in my online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic”, reversed “Difficulties with technology are the reason I have been late to or had to miss online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic”, and reversed “The technology I use to attend online classes and complete my schoolwork during COVID-19 causes me stress”. Continuous composite scores were analyzed without applying thresholds or cutoffs. Higher scores on these items indicate students’ higher access to technology. Cronbach’s alpha for this 5-item scale was α = 0.72, which is considered acceptable for scales with a small number of items (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

The financial stress scale consisted of three items adapted to reflect pandemic-related financial concerns, consistent with existing literature (Robillard et al., 2021). There were no missing responses for any items on this scale. The financial stress variable was created by summing the items: “I am stressed about my financial situation as a result of COVID-19”, “I am unsure if I will be able to afford tuition if COVID-19 continues much longer”, and “I am more stressed about money now than I was prior to the onset of COVID-19”. Continuous composite scores were used without thresholds or cutoffs. Higher scores on these items indicate higher levels of financial stress. The reliability analysis for this 3-item scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.83, indicating good internal consistency, even for a scale with a small number of items (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). For academic performance, we asked students to self-report their GPA since identifiable information such as official academic records was not collected to protect participants’ anonymity. Studies generally show a very strong correlation between self-reported and official GPAs, with correlations as high as 0.97 (Cassady, 2001). This indicates that self-reported GPAs are typically accurate.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection occurred in Spring 2021. All students who were enrolled at the researchers’ public, four-year research-intensive university during both Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 semesters were eligible to participate in the study. First, they received an email invitation from the Office of Student Affairs. They first provided informed consent, which was included in the initial questionnaire. The Qualtrics questionnaire was administered electronically. Students were asked to reflect on their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly during the Fall 2020 semester. As noted, previously, the Qualtrics questionnaire asked participants to detail their use of technology, challenges they faced, and the financial stress they experienced during the pandemic. Skip logic was used in this questionnaire, where participants were asked to respond to questions that were relevant to them based on their previous answers. All responses were anonymous, and the questionnaire took about 20 min to complete. Participants were compensated for their time by receiving Sona credits, which could have been used to earn extra credit in their courses if their professors allowed it.

3. Results

3.1. What Are the Differences in Technology Access Between First Generation and Continuing Generation College Students?

First, we examined if FGCS and CGCS differed by gender or academic year. Initial Chi-square analyses revealed no statistically significant differences between FGCS and CGCS for gender, χ2(3, N = 430) = 5.43, p = 0.143, or their academic year, χ2(4, N = 430) = 5.46, p = 0.243. Thus, these variables were not considered as covariates in subsequent analysis. Next, two one-way ANOVAs were run to assess if technology access and financial stress differed for students based on their racial/ethnic identity. The results revealed that there were no significant differences for technology access, F(5, 424) = 0.71, p = 0.614, ηp2 = 0.01, and only a marginal difference in financial stress F(5, 424) = 2.15, p = 0.059, ηp2 = 0.02. Thus, we did not control for racial/ethnic identity in subsequent analyses. Frequencies of the technology access and financial stress items for FGCS and CGCS are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Differences in Technology Access and Financial Stress between FGCS and CGCS.

Next, to test how academic performance related to technology access and financial stress, Pearson’s correlational analyses were run. Academic performance was positively related to technology access, r(407) = 0.11, p = 0.026, and negatively related to financial stress, r(407) = −0.26, p < 0.001. Technology access was also negatively related to financial stress, r(428) = −0.35, p < 0.001. The correlations between these variables for FGCS and CGCS are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations between Study Variables for FGCS and CGCS.

Next, two one-way ANOVAs were conducted to test if technology access and financial stress differed based on generation status (FGCS and CGCS). In the first analysis, generation status was entered as the categorical independent variable, and technology as the continuous dependent variable. The analysis revealed that CGCS had a statistically significant advantage in technology access compared to FGCS, F(1, 428) = 4.06, p = 0.045, ηp2 = 0.01. While the effect size was small (Cohen, 1988), this finding is noteworthy given that the university requires all students to have computers meeting specific minimum requirements. In the second analysis, generation status (FGCS and CGCS) was entered as the categorical independent variable, and financial stress as the continuous dependent variable. The analysis showed that FGCS reported higher levels of financial stress compared to CGCS, F(1, 428) = 46.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, which indicates a medium to large effect size per Cohen’s guidelines (1988).

3.2. How Do Technology Access and Students’ Reported Levels of Financial Stress Relate to Academic Performance for Both FGCS and CGCS?

The study further explored the relation between technology access and academic performance for the two groups of students. Specifically, academic performance was regressed on technology access for both FGCS and CGCS. The multiple linear regression model explained 4% of the variance in GPA, suggesting that technology access plays a small, but significant role in FGCS’s academic performance. For FGCS, greater technology access and use was significantly positively related to higher academic performance, b = 0.02, F(1, 118) = 4.59, p = 0.034, f2 = 0.04. In contrast, for CGCS, the regression model explained only a negligible portion of the variance (R2 = 0.005). Technology access was not significantly related to academic performance for CGCS, b = 0.01, F(1, 288) = 1.36, p = 0.245, f2 = 0.00.

Next, academic performance was regressed on technology access and financial stress. When financial stress was included in the model, the overall significance remained for both FGCS, F(2, 117) = 4.67, p = 0.011, f2 = 0.04, and CGCS, F(2, 287) = 10.5, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.04. However, technology access was no longer a significant unique predictor of academic performance for either group (p > 0.15). This suggests that financial stress may be a more influential factor in explaining academic outcomes for both FGCS and CGCS. Moreover, it is plausible that financial stress may play a more nuanced role, such as moderating the relation between technology and academic outcomes.

3.3. Do Technology Access and Financial Stress Interact to Influence Their Academic Outcomes?

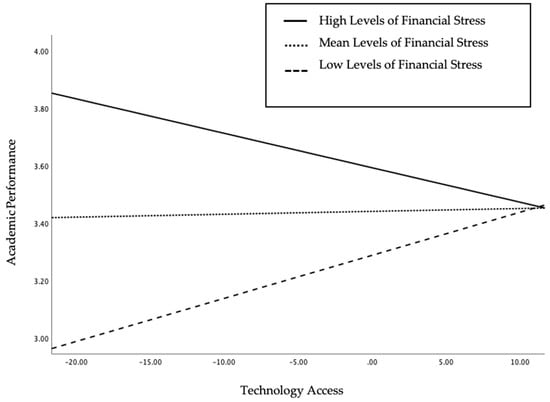

To assess moderation effects, academic performance was regressed on technology access, financial stress, and their interaction term. Predictor variables were mean-centered prior to analysis. The multiple linear regression model revealed that approximately 8% of the predictable variance in GPA was explained by technology access, financial stress, and their interaction term, R2 = 0.08, F(3, 405) = 12.36, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.09. There was a small to medium effect of financial stress on academic performance at the mean level of financial stress, b = −0.31, t(405) = -5.27, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.07. However, technology access did not have a significant effect on academic performance at the mean level of financial stress, b = 0.001, t(405) = 0.22, p = 0.83, f2 = 0.00. Moderation was inferred given the significant interaction of financial stress and technology access, b = 0.003, t(405) = 2.59, p = 0.010, f2 = 0.02, indicating a small but significant effect size. This suggests that the effect of technology access on academic performance varied depending on the level of financial stress.

Following guidelines suggested by Aiken and West (1991), the effect of technology access was evaluated at three levels of financial stress: low level of financial stress (one SD below the mean of financial stress), average level of financial stress, and high level of financial stress (one SD above the mean). This tested how varying levels of financial stress moderated the relation between technology access on academic performance. As Figure 1 shows, there was a marginally significant positive effect of technology access on academic performance when financial stress was high, b = 0.01, t(405) = 1.96, p = 0.051, f2 = 0.00, compared to when financial stress was low, b = −0.01, t(405) = −1.49, p = 0.137, f2 = 0.00. This indicates that the relation between technology access and academic outcomes was moderated by financial stress, with opposite effects when financial stress was very high and very low.

Figure 1.

Plot of Simple Slopes of Technology Access on Academic Performance at levels of Financial Stress.

4. Discussion

4.1. What Are the Differences in Technology Access Between First Generation and Continuing Generation College Students?

This study focused on academic performance as measured by GPA of first-generation (FGCS) and continuing generation students (CGCS) during the Fall 2020 semester when COVID-19 was still in its pandemic stage. Specifically, it investigated the similarities and differences in the technology access, and financial stress experienced between first and continuing generation college students. The results showed that first generation students faced greater disadvantages in overall technology access compared to their continuing generation peers. This finding aligns with previous research (Deng & Yang, 2021; Soria et al., 2020), highlighting that during the pandemic COVID-19 first-generation students often lacked adequate study spaces and reliable technology. This made it more difficult for them to adapt to virtual instruction and attend scheduled classes (Deng & Yang, 2021; Soria et al., 2020). Similarly, we found that compared to their CGCS peers, FGCS reported experiencing more technological difficulties with classes, exams, and/or assignments since the onset of COVID-19, less sufficient access to technology, as well as having to share their devices (such as laptop, tablet, phone) with someone else.

The results of this study confirm that the digital divide disproportionally affects FGCS and CGCS students (Van Dijk, 2017; Whitley et al., 2018). This divide worsened during the pandemic, highlighting the inadequate study spaces and limited access to technology (Soria et al., 2020; Barber et al., 2021). Drawing parallels with Wilcox et al. (2022)’ study, FGCS in the current study also reported higher financial stress than CGCS. This has been suggested to be due to their caregiving responsibilities, financial responsibilities to assist their families (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017; Covarrubias et al., 2019; Deng & Yang, 2021), or their experience with food and housing insecurity (Soria et al., 2020).

4.2. How Do Technology Access and Students’ Reported Levels of Financial Stress Relate to Academic Performance for Both FGCS and CGCS?

A second aim was to explore how technology access, and the reported levels of financial stress relate to academic performance for both FGCS and CGCS, as well as if technology access and financial stress interact to influence their academic outcomes. The results revealed interesting patterns. For FGCS, greater access to technology significantly predicted higher academic performance. This indicates that technology access may play an important role in supporting academic success for FGCS possibly by enhancing students’ ability to engage with course materials, complete assignments efficiently, or access academic resources. Similarly, D’Angelo (2018) highlighted the importance of technology access in academic achievement. It boosts student motivation, deepens understanding of course content, and ultimately improves performance (D’Angelo, 2018). However, this relation between technology access and academic success appears to differ for continuing-generation students. For CGCS, technology access was not a significant predictor of academic performance. This finding might suggest that the role of technology access is less pivotal for students who already have a stable academic foundation and are well-integrated into the college environment—unlike many FGCS (Aruguete & Katrevich, 2017; Irlbeck et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2020).

When financial stress was added to the regression model, the unique predictive power of technology access on academic performance diminished for FGCS. This suggests that financial stress is a more robust determinant of academic performance, potentially overshadowing the benefits of technology access. For first-generation students, financial stress might exacerbate existing challenges, including those related to technology. Thus, it might impact academic outcomes more heavily. McCullough (2022) similarly found that while technology access can support academic achievement, financial stress plays a more dominant role. It limits the overall academic success of first-generation students by overshadowing the advantages of technology access. However, another plausible explanation is that the effects of technology access change at levels of financial stress.

4.3. Do Technology Access and Financial Stress Interact to Influence Their Academic Outcomes?

The additional moderation analyses findings indicate that overall financial stress significantly moderates the relation between technology access and academic performance. At average levels of financial stress, technology access had no notable effect on academic performance. However, when financial stress was higher, technology access had a marginally positive effect on academic performance, possibly providing essential support amid financial strain. Conversely, at lower financial stress, technology access showed a non-significant negative effect, potentially due to increased distractions. This suggests that under high financial pressure, technology access becomes a critical resource for academic performance. Although the observed interaction yielded a small effect size, such effects can have substantial implications when applied across large populations or repeated over time. As Funder and Ozer (2019) argue, small effects should not be dismissed considering their theoretical and practical importance. This is especially true for when variables are modifiable, widely experienced, and have cumulative or population-level impacts (Funder & Ozer, 2019). While financial stress has been consistently associated with mental health outcomes in higher education (McCloud & Bann, 2019), the present study’s results emphasize that financial stress is shaping the impact of technology access on students’ academic outcomes, regardless of their generational status.

4.4. Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

The nuanced findings of this study highlight the importance of addressing both technological and financial barriers in supporting the academic success of first-generation students. While the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the stressors, support systems, and academic challenges identified may extend beyond that context. The pandemic accelerated the integration of digital technologies across various sectors, including higher education (Yao et al., 2024). Thus, issues related to online learning, such as technology access as well as financial stress are still highly relevant as hybrid and remote learning models continue to affect students (Walker & Voce, 2023; Yao et al., 2024). Additionally, given that financial stress disproportionately affects FGCS, targeted interventions are essential. Mentorship programs, financial counseling, and peer support networks designed specifically for first-generation students can help mitigate these challenges and improve academic outcomes (Zuo et al., 2017). Beyond providing resources, universities should also implement initiatives that actively support students in utilizing them. For example, structured guidance on how to navigate financial aid services, workshops on maximizing academic support centers, and outreach efforts that connect students to tutoring and advising can enhance resource accessibility (Amaya, 2010).

At the same time, universities must consider how to sustain academic support in scenarios where students are forced into isolation, such as extreme weather events or public health crises. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need for institutions to be prepared for remote learning disruptions. Future preparedness plans should include expanding access to virtual learning platforms. This includes ensuring students have the necessary technology for remote coursework, and establishing emergency financial relief programs for those facing economic hardship. By proactively developing strategies that maintain academic support during closures, universities can help prevent increased disparities among vulnerable student populations.

The generalizability of these findings is a potential limitation, as the study included only students from a mid-sized public university in the U.S. Students’ socioeconomic inequities. Student experiences can vary significantly depending on the type of institution they attend (Dowd et al., 2008), such as community colleges, large public universities, or private schools. As such, caution is needed when applying these results to different contexts. Further, this cross-sectional study does not establish a definitive causal relation between financial stress, technology access, and academic performance, as other unmeasured factors—such as family responsibilities—may also play a role. Lastly, the use of self-reported data may have introduced a potential for bias. Specifically, the temporal gap between the semester participants were asked to reflect on (Fall 2020) and when the data were collected (Spring 2021) may have impacted their responses. Given the rapidly changing circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, students’ recollections could have been shaped by more recent experiences or evolving personal and academic challenges, potentially affecting the accuracy or consistency of their responses. Nevertheless, the study offers meaningful insights into the effects of financial stress and technology access on academic performance. The findings are both relevant and valuable for future research and student support initiatives.

Future research should consider conducting longitudinal studies that track the long-term effects of financial stress and technology access on academic performance. Following students across multiple semesters or years would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how these factors impact persistence and overall academic success. Additionally, research should explore whether navigating these challenges fosters valuable life skills, such as resilience, adaptability, and time management. These skills may contribute to long-term professional success. While financial stress and technological barriers can hinder academic progress, they may also cultivate problem-solving abilities and perseverance that benefit students in their careers.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the impact of technology access and financial stress on academic performance, particularly for first-generation college students. Findings revealed that under conditions of high financial stress, access to technology served as a key protective factor in supporting academic success. Technology access likely enables students to consistently engage with course materials, participate in remote instruction, and submit their assignments on time. However, when financial stress was low, technology access showed little to no effect, suggesting that financial burden plays a moderating role in the utility of technological resources. As a result, efforts to support student success must prioritize alleviating financial burdens, especially for FGCS, who face unique challenges in navigating higher education.

Future research should extend these findings by examining how financial stress and technology access affect not just GPA, but also retention, mental health, and post-graduation outcomes. Longitudinal studies that follow FGCS and CGCS across several semesters would offer insights into whether these stressors accumulate or shift over time.

Moving forward, universities must adopt a comprehensive approach to student support that combines financial assistance with access to technology and other academic resources. While these resources exist, FGCS may not always be aware of them or may face barriers that prevent them from fully benefiting. Thus, institutions should embed culturally responsive mentorship programs and outreach efforts that connect FGCS with academic and financial resources early in their college journey. By addressing the financial and technological needs of students through a more intentional approach, institutions can play a pivotal role in closing the achievement gap between first-generation and continuing-generation students, ultimately promoting greater equity and academic success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K. and S.S.; methodology, B.K. and S.S.; software, B.K.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, B.K.; investigation, S.S.; resources, S.S.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.; writing—review and editing, B.K. and S.S.; visualization, B.K.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) (Approval Code: #531 Approval Date: 2 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the students from the Children and Families, Schooling and Development Lab who made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FGCS | First-Generation College Students |

| CGCS | Continuing-Generation College Students |

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, H., Yingxiu, Y., Samed, A., & Alkhalifah, A. (2021). Technology integration in higher education during COVID-19: An assessment of online teaching competencies through technological pedagogical content knowledge model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 736522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, B. A., Garriott, P. O., & Keene, C. N. (2016). Outcomes of social class and classism in first- and continuing-generation college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(4), 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaya, I. (2010). How first-generation college and underrepresented students can overcome obstacles to attaining a college education: Handbook for a new family tradition [Master’s thesis, Texas State University]. Available online: https://digital.library.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/3754/fulltext.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Amirkhan, J. H., Manalo, R., Jr., & Velasco, S. E. (2023). Stress overload in first-generation college students: Implications for intervention. Psychological Services, 20(3), 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruguete, M. S., & Katrevich, A. V. (2017). Recognizing challenges and predicting success in first-generation university students. Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, 18(2), 40–44. Available online: https://www.jstem.org/jstem/index.php/JSTEM/article/view/2233 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Baker, A. R., & Montalto, C. P. (2019). Student loan debt and financial stress: Implications for academic performance. Journal of College Student Development, 60(1), 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, P. H., Shapiro, C., Jacobs, M. S., Avilez, L., Brenner, K. I., Cabral, C., Cebreros, M., Cosentino, E., Cross, C., Gonzalez, M. L., Lumada, K. T., Menjivar, A. T., Narvaez, J., Olmeda, B., Phelan, R., Purdy, D., Salam, S., Serrano, L., Velasco, M. J., … Levis-Fitzgerald, M. (2021). Disparities in remote learning faced by first-generation and underrepresented minority students during COVID-19: Insights and opportunities from a remote research experience. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 22(1), 22.1.54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A., Karakaya, K., Turk, M., Karakaya, Ö., & Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on education: A meta-narrative review. TechTrends, 66(6), 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1988). Interacting systems in human development: Research paradigms: Present and future. In N. Bolger, A. Caspi, G. Downey, & M. Moorehouse (Eds.), Persons in context: Developmental processes (pp. 25–49). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cassady, J. C. (2001). Self-reported GPA and SAT: A methodological note. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(1), 12. Available online: https://openpublishing.library.umass.edu/pare/article/1381/galley/1332/view/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Cataldi, E. F., Bennett, C. T., & Chen, X. (2018). First-generation students: College access, persistence, and postbachelor’s outcomes (NCES 2018-421). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2018421 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias, R., Valle, I., Laiduc, G., & Azmitia, M. (2019). “You never become fully independent”: Family roles and independence in first-generation college students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(4), 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, C. (2018). The impact of technology: Student engagement and success. In Technology and the curriculum: Summer 2018. University of Ontario Institute of Technology. Available online: https://pressbooks.pub/techandcurriculum/chapter/engagement-and-success/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Deng, X. (N.), & Yang, Z. (2021). Digital proficiency and psychological well-being in online learning: Experiences of first-generation college students and their peers. Social Sciences, 10(6), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, M. D. (2015). Measuring student engagement in the online course: The online student engagement scale (OSE). Online Learning Journal, 19(4), n4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, A. C., Cheslock, J. J., & Melguizo, T. (2008). Transfer access from community colleges and the distribution of elite higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(4), 422–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K. (2020). When coronavirus closes colleges, some students lose hot meals, health care, and a place to sleep. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 11, 28–43. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/when-coronavirus-closes-colleges-some-students-lose-hot-meals-health-care-and-a-place-to-sleep/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galina, B. (2016). Teaching first-generation college students. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Available online: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-first-generation-college-students/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Goldman, J., Heddy, B. C., & Cavazos, J. (2020). First-generation college students’ academic challenges understood through the lens of expectancy value theory in an introductory psychology course. Teaching of Psychology, 49(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A. L., McCrory Calarco, J., & Lynch, T. (2020). Technology problems and student achievement gaps: A validation and extension of the technology maintenance construct. Communication Research, 47(5), 750–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, W. H., & Huffman, A. H. (2012). Beyond basic study skills: The use of technology for success in college. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlbeck, E., Adams, S., Akers, C., Burris, S., & Jones, S. (2014). First generation college students: Motivations and support systems. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloud, T., & Bann, D. (2019). Financial stress and mental health among higher education students in the UK up to 2018: Rapid review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health, 73(10), 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K. A. (2022). First-generation college students: Factors that impact stress and burnout, academic success, degree attainment, and short- and long-term career aspirations [Doctoral dissertation, Baker University]. Available online: https://www.bakeru.edu/images/pdf/SOE/EdD_Theses/McCullough_Karen.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Means, B., & Neisler, J. (2021). Digital learning during the pandemic: Emerging evidence of an equity gap. Digital Promise, 25(1), 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L. T., Stephens, N. M., Townsend, S. S., & Goudeau, S. (2020). Access is not enough: Cultural mismatch persists to limit first-generation students’ opportunities for achievement throughout college. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1112–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M., Schnakovszky, C., Herghelegiu, E., Ciubotariu, V., & Cristea, I. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of educational process: A student survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robillard, R., Saad, M., Edwards, J. D., Solomonova, E., Pennestri, M.-H., Daros, A., Veissière, S. P. L., Quilty, L., Dion, K., Nixon, A., Phillips, J. L., Bhatla, R., Spilg, E., Godbout, R., Yazji, B., Rushton, C. H., Gifford, W., Gautam, M., Boafo, A., & Kendzerska, T. (2021). Social, financial and psychological stress during an emerging pandemic: Observations from a population web-based survey in the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open, 11(2), e043805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K. M., Horgos, B., Chirikov, I., & Jones-White, D. (2020). First-generation students’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. University Digital Conservancy. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/214934 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, R. J., Blais, M. R., Brière, N. M., & Pelletier, L. G. (1989). Construction et validation de l’Échelle de Motivation en Éducation (EME). Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 21, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2012). The evolution of the digital divide: The digital divide turns to inequality of skills and usage. In Digital Enlightenment Yearbook (pp. 57–75). IOS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2017). Digital divide: Impact of access. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R., & Voce, J. (2023). Post-pandemic learning technology developments in UK higher education: What Does the UCISA evidence tell us? Sustainability, 15(17), 12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekerle, C., Daumiller, M., & Kollar, I. (2020). Using digital technology to promote higher education learning: The importance of different learning activities and their relations to learning outcomes. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, S. E., Benson, G., & Wesaw, A. (2018). First-generation student success: A landscape analysis of programs and services at four-year institutions. Center for First-generation Student Success, NASPA–Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, and Entangled Solutions. Available online: https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/dmfile/NASPA-First-generation-Student-Success-FULL-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Wilcox, M. M., Pietrantonio, K. R., Farra, A., Franks, D. N., Garriott, P. O., & Burish, E. C. (2022). Stalling at the Starting Line: First-generation college students’ debt, economic stressors, and delayed life milestones in professional psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 16(4), 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X., Xu, Z., Škare, M., & Wang, X. (2024). Aftermath on COVID-19 technological and socioeconomic changes: A meta-analytic review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 202, 123322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C., Mulfinger, E., Oswald, F. L., & Casillas, A. (2017). First-generation college student success. In R. S. Feldman (Ed.), The first year of college: Research, theory, and practice on improving the student experience and increasing retention (pp. 55–90). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).