Middle Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence: A Scoping Review and Empirical Exploration

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Middle Leadership

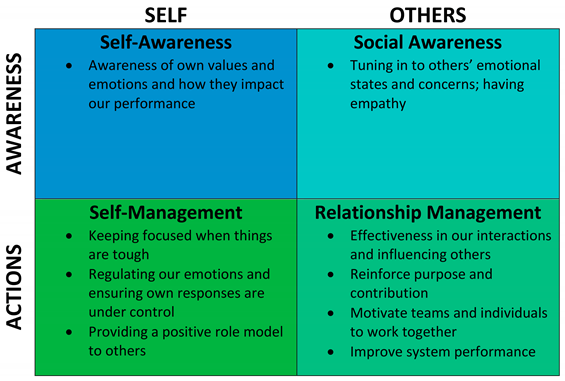

1.2. School Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence

2. Research

2.1. Current Study

2.2. Method

- RQ1: What SEI-specific components and competencies are important to middle leadership practices for positive outcomes?

- RQ2: What is the impact, if any, of leadership role, experience, or age on a middle leader’s social emotional intelligence?

- RQ3: How can social and emotional intelligence be developed to support the well-being of middle leaders and strengthen their leadership practices?

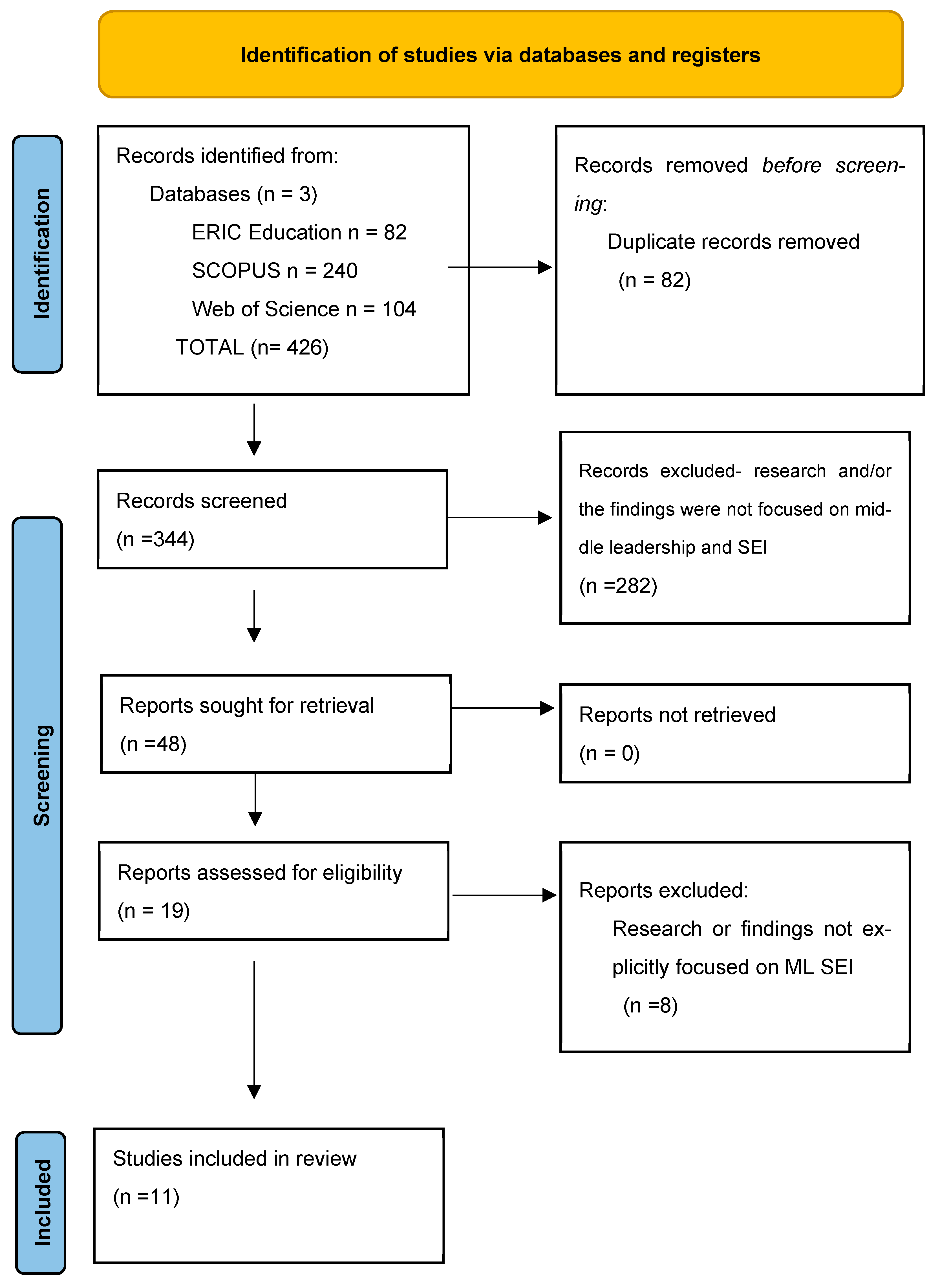

2.3. Phase 1: Scoping Review of Literature

2.4. Phase 2: Middle Leader Interviews

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. What SEI Specific Components and Competencies Are Important to Middle Leadership Practices for Positive Outcomes?

3.1.1. Scoping Review Findings

3.1.2. Middle Leader Interview Findings

“I think that within the middle leadership role the pressure is on, … because you’re that middle, you know, between the teachers who you work with daily and the senior leadership, so yes high emotional intelligence, being aware of what you are doing, saying to set a positive tone with all of them, it’s what builds relationships and creates the team culture that’s needed to do the work and it’s what breaks a relationship when you don’t use it”.

“For me it’s sort of drawing on the self-management side of things. We (middle leaders) see ourselves as role models to our students, and also other staff members and need to manage ourselves despite the workload… and to deal with the unknown of the day which can be emotional, … at the end of the day, being aware of how we feel, the emotional impact of the work and what we do is the means of helping us cope better which can help everyone”.

“Most of my day-to-day problems with my team aren’t content, curriculum or pedagogy, they are literally understanding and helping people cope with these things, the decisions and the changes, … I must really balance that and find ways to help them with managing the work but also their feelings and mine”.

“I’m just very cognizant of how everyone’s feeling … reading the room and reading people’s body language and picking up those queues. Knowing when teachers are feeling overwhelmed and when to hold back things, providing that support they need … it’s not only the talking, but the doing stuff, it’s this that brings the team closer together, more open and collaborative”.

“I consciously made the choice to give time to my colleagues, my peers but also to myself… I practice a little self-care routine. I definitely noticed over time I became more resilient”.

“I think self-awareness is really important, if you really know yourself, you’re open to reflecting on what’s happening the good and the bad … and as a ML you need to be authentic and there’s always need for growth”.

“Really, it’s about being real, consistent, approachable and knowing you don’t have all the answers, so it’s being self-aware, really its essential to keeping relationships and people’s trust”.

3.1.3. Synthesis of Phase 1 and 2 Results

3.2. RQ2: What Is the Impact, If Any, of Leadership Role, Experience or Age on a Middle Leader’s Social Emotional Intelligence?

3.2.1. Scoping Review Findings

3.2.2. Middle Leader Interview Findings

“It’s a deliberate act, I think. What’s more important than the age, or position is the investment for any school leader, it is intentional professional development and intentional professional growth plans with a social and emotional focus that leads to positive leadership outcomes”

“Self-awareness is probably the key thing because I know people that have experience but aren’t necessarily self-reflective… what is important we don’t know it all, … one of the barriers is not actually realizing the level of social, emotional intelligence that is needed within middle leadership”

“Coming into it (middle leadership) when I was young was tough, I felt so under pressure, not confident … it really impacted how I felt, how I led, I was reactionary when dealing with so many different colleagues”

3.2.3. Synthesis of Phase 1 and 2 Results

3.3. RQ3: How Can Social Emotional Intelligence Be Developed to Support the Wellbeing of Middle Leaders and Strengthen Their Leadership Practices?

3.3.1. Scoping Review Findings

3.3.2. Middle Leader Interview Findings

“It’s like a muscle, you know, you can work towards it, build it … it’s now more talked about, but it is providing opportunities for, leaders including middle leaders to understand and develop these really important capacities”.

“How you empathize, react and interact is the core of what we do (middle leaders) so without understanding and enacting it (SEI) from the start, when you come into the job, you can end up damaging your relationships”

“My experience in having meaningful self-reflection to develop my self-awareness of how I am leading and why I am leading this way and what is the impact… understanding my colleagues’ reactions, for me is having middle leader or executive level team mentorship, coupled with an individual school exec or principal mentor. Any one-off PL can be good but removed from your context”.

3.3.3. Synthesis of Phase 1 and 2 Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PL | Professional Learning |

| SEI | Social Emotional Intelligence |

| MLs | Middle Leaders |

| ML | Middle Leadership |

Appendix A. Description of the Reviewed Studies

| Authors | Title | Country | Methodology | Focus of Paper in Relation to MLs SEI |

| 1 Benson et al. (2014) | Investigating trait emotional intelligence among school leaders: demonstrating a useful self-assessment approach. | England | Survey Instrument: Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire Semi-structured interviews with senior and middle leaders (number not specified) | Investigated trait EI among middle and senior leaders Findings: Emotion regulation, impulsiveness and stress management higher for senior school leaders compared to MLs; age positively impacted emotional perception, emotion expression, empathy and relationships, no EI gender differences |

| 2 Ghamrawi (2010) | No Teacher Left Behind: Subject Leadership that Promotes Teacher Leadership | Lebanon | 51 Semi-structured interviews with principals, subject leaders, and classroom teachers | Investigated teacher leadership in relation to nourishing teacher leadership in their departments SEI FINDING: SEI components identified as important for MLs leading teams |

| 3 Ghamrawi et al. (2023) | Stepping into middle leadership: a hermeneutic phenomenological study | Lebanon | Interpretive hermeneutic phenomenological study of six K-12 school middle leaders | Investigated novice middle leaders over 3-year period as they transition into middle leadership roles SEI FINDING: Identified specific EI personal components and competencies novice middle leaders perceive as supportive for their role |

| 4 Gutiérrez-Cobo et al. (2019) | A Comparison of the Ability Emotional Intelligence of Head Teachers With School Teachers in Other Positions | Spain | Mayer-Salovey-Caruso emotional intelligence test (MSCEIT) 393 completed the MSCEIT (35 head teachers, 39 middle leaders, 236 tutors, and 86 teachers) | Investigated SEI Compared emotional intelligence between head teachers, middle leaders, tutors, and teachers Findings: Head Teachers (principals) were found to have a higher ability to understand emotional information, emotions within relationships, and appreciate emotional meanings |

| 5 Lai and Huang (2022) | “I Was a Class Leader”: Exploring a Chinese English Teacher’s Negative Emotions in Leadership Development in Taiwan | Taiwan | 1 Case Study | Examined the emotionality of teacher leadership development SEI FINDING: Impact of a teacher leader’s negative emotions |

| 6 Lambert (2020) | Emotional awareness amongst middle leadership | England | Geneva Emotion Recognition Test (GERT) 83 completed the GERT 42 Teacher, 23 Middle leaders, 11 Senior Leaders, 1 Head Teacher/Principal | Investigated EI Explore middle leaders’ ability to recognise emotions in the context of workplace research, and to propose measures that might support them in their role. Findings: Head teachers (principals) and teachers have higher levels of emotional recognition than middle leaders |

| 7 Lambert (2022) | The practical application on middle leaders of performing coaching interventions on others to support the development of their own emotional recognition. | England | Geneva Emotion Recognition Test (GERT) 24 school middle leaders | Investigated EI Explored possible changes to MLs emotional recognition capabilities after being a coach Findings: MLs emotional recognition capabilities improve after coaching staff member |

| 8 Lipscombe et al. (2023) | Middle leaders’ facilitation of teacher learning in collaborative teams | Australia | 3 Case Studies 3 Middle leaders, 13 classroom teachers | Investigated the micro-processes MLs enact when facilitating teacher teams SEI FINDING: SEI competency of empathy identified as important for ML’s facilitating teams |

| 9 Loughland and Ryan (2022) | Beyond the measures: the antecedents of teacher collective efficacy in professional learning | Australia | Case Study 8 Teacher Leaders | Investigated how emerging teacher leaders operationalised a sense of collective efficacy in their professional learning teams. SEI FINDING: SEI components identified as important for MLs building collective efficacy |

| 11 Shaked (2024) | Enabling factors of instructional leadership in subject coordinators | Israel | Interviews with 24 elementary school subject coordinators focused enabling factors for leading teaching and learning in their school | Investigated the enabling factors of instructional leadership in subject coordinators (middle leaders) SEI FINDING: EI component of empathy identified as important for MLs to establish and maintain productive relationships with their team |

| 11 Wong et al. (2010) | Effect of Middle-level Leader and Teacher Emotional Intelligence on School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction | Hong Kong | Study 1 107 teachers surveyed on the attributes of successful. middle-level leaders in their schools. Study 2 3866 schoolteachers and middle- leaders EI was investigated using a 16-item Wong and Law (2002) and job satisfaction level using Job Diagnostic Survey. | Investigated EI Impact of ML and teacher EI on teachers’ job outcomes. Findings: MLs EI found to be important to their success, and for motivating the teachers they lead |

Appendix B. ML Information Prior to Interview

| Components | Competencies |

| Self-Awareness | Emotional Self-awareness, Self Confidence, Accurate Self- Assessment |

| Social Awareness | Empathy, Organizational Awareness, Service Orientation |

| Self-Management | Self-Control, Initiative, Transparency, Adaptability, Achievement Drive |

| Relationship Management | Developing Others, Influence, Inspirational Leadership, Teamwork and Collaboration, Change Catalyst, Conflict Management, Building Bonds |

Appendix C. The Alignment of Research Questions, Interview Questions and Themes

| Research Question | Scoping Literature Themes | Interview Questions | Additional Theme(s) from ML Interviews and Key Theme Quote |

| What SEI specific components and competencies are important to middle leadership practices for positive outcomes? | SEI Components For specific ML practices Empathy

Self-management

| Reflecting on your work as a middle leader and the SEI components and competencies summary provided, which ones do you draw upon in your work. Can you give explicit examples? Understanding the different SEI components and competencies, which ones do you perceive as essential for a ML to be effective? Can you explain why they are important? | Empathy Maintain collegial relationships “Practical Empathy” Support ML wellbeing Self-management Role modelling positive emotions To prevent harming relationships Self-awareness Understand one’s emotions Manage stress Self-awareness for self-care/wellbeing Open, authentic Building high level of self-awareness, being able to manage my own emotions… managing emotions in a healthy way, knowing how to do that and modelling it… helps create stability and positivity in the team. Adam |

| What is the impact, if any, of leadership role, experience or age on a middle leader’s social emotional intelligence? | School leaders higher SEI v ML Competencies of emotional recognitions, management, expression, understanding School leaders higher SEI v ML stress management Age Possibly supports emotional awareness and regulation | Do you see that social emotional intelligence may be impacted by age or experience? What has been your experiences as a ML or working with other MLs in relation to recognizing and managing emotional, do you see differences between principals and MLs? Do you think there are any challenges for ML and SEI? | SEI developed by Experience Self-reflection Time Impact of ML on SEI First leadership position Different to classroom teaching Intensity of the role I’ve noticed that shift between this role and being mainly on class, it’s the opportunity to tune into the emotional state of others, having that awareness of others is the thing, because I’ve got time with them and for myself to reflect. |

| How can social emotional intelligence be developed to support the well-being of middle leaders and strengthen their leadership practices? | Develop SEI Reflective tools Mentoring Collaborating with other MLs The impact of ML task vs. relational work on ML SEI ML development Emotional awareness of self and colleagues Emotional management/negative emotions | As we have discussed SEI within middle leadership, how could it be further developed? What is your experience of professional learning in this area? How can PL support your: What you do as a ML Managing stress and wellbeing What strategies have you used yourself to develop SEI? | SEI can be developed Targeted SEI PL required Importance of ML SEI professional learning First leadership role Emotionality of being a ML Stress and Wellbeing Support reflection and SEI learning Mentor or critical friend PD Further study Being mentored by people who have a strong emotional intelligence has helped me… it’s those conversations they are really important, reflective and development focused. Brad |

References

- Ainsworth, S., Da Costa, M., Davies, C., & Hammersley-Fletcher, L. (2022). New perspectives on middle leadership in schools in England-Persistent tensions and emerging possibilities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(3), 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, W. (2011). The heart of the head, the emotional dimension of school leadership. An examination and analysis of the role emotional intelligence plays in successful secondary school and academy leadership [Ph.D. thesis, University of Hull]. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2024). Professional standards for middle leaders. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/lead-develop/teachers-who-lead/middle-leadership-standards (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Benson, R., Fearon, C., McLaughlin, H., & Garratt, S. (2014). Investigating trait emotional intelligence among school leaders: Demonstrating a useful self-assessment approach. School Leadership & Management, 34(2), 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I., & Eyal, O. (2015). Educational leaders and emotions: An international review of empirical evidence 1992–2012. Review of Educational Research, 85(1), 129–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I., & Eyal, O. (2020). A model of emotional leadership in schools: Effective leadership to support teachers’ emotional wellness. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaik Hourani, R., Litz, D., & Parkman, S. (2021). Emotional intelligence and school leaders: Evidence from Abu Dhabi. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 49(3), 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G., O’Connor, J., Harris, S., & Frick, E. (2018). The influence of emotional intelligence on the overall success of campus leaders as perceived by veteran teachers in a rural midsized East Texas public school district. Educational Leadership Review, 19(1), 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinia, V., Zimianiti, L., & Panagiotopoulos, K. (2014). The role of the principal’s emotional intelligence in primary education leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(4), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D. A., & Rao, C. (2019). Teachers as reform leaders in Chinese schools international. Journal of Educational Management, 33(4), 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, J. (2011). Emotional intelligence: A study of female secondary school headteachers. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39(2), 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniëls, E., Hondeghem, A., & Dochy, F. (2019). A review on leadership and leadership development in educational settings. Educational Research Review, 27, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. (2019). The roles of middle leaders in schools: Developing a conceptual framework for research. Leading and Managing, 25(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Döringer, S. (2020). ‘The problem-centred expert interview’. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Groves, C., Attard, C., Grootenboer, P., & Tindall-Ford, S. (2023). Middle leading practices of facilitation, mentoring, and coaching for teacher development: A focus on intent and relationality. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 19(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Groves, C., & Grootenboer, P. (2021). Conceptualising five dimensions of relational trust: Implications for middle leadership. School Leadership & Management, 41(3), 260–283, (Erratum in “Correction”, 2021, School Leadership & Management, 41(4–5), 488–491). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Groves, C., Grootenboer, P., & Ronnerman, K. (2016). Facilitating a culture of relational trust in school-based action research: Recognising the role of middle leaders. Educational Action Research, 24(3), 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V., Wong, W., & Noonan, M. (2023). Developing adaptability and agility in leadership amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Experiences of early-career school principals. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(2), 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2018). Doing qualitative data collection—Charting the routes. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 3–16). SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Ghamrawi, N. (2010). No teacher left behind: Subject leadership that promotes teacher leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(3), 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Ghamrawi, N., Shal, T., & Ghamrawi, N. A. R. (2023). Stepping into middle leadership: A hermeneutic phenomenological study. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Realizing the importance of emotional intelligence. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Leal, R., Holzer, A. A., Bradley, C., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Patti, J. (2021). The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: A systematic review. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P. (2018). The practices of school middle leadership: Leading professional learning. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., & Ronnerman, K. (2020). Relating, trust and dialogic practice in middle leading. In P. Grootenboer, C. Edwards-Groves, & K. Ronnerman (Eds.), Middle leadership in schools (pp. 49–76). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P., Tindall-Ford, S., Edwards-Groves, C., & Attard, C. (2023). Establishing an evidence-base for supporting middle leadership practice development in schools. School Leadership & Management, 43(5), 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, D. (2019). School middle leaders in Australia, Chile and Singapore. School Leadership & Management, 39(3–4), 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Gutiérrez-Cobo, M. J., Rosario, C., Rodríguez-Corrales, J., Megías-Robles, A., Gómez-Leal, R., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2019). A comparison of the ability emotional intelligence of head teachers with school teachers in other positions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley-Fletcher, L., Clarke, M., & McManus, V. (2018). Agonistic democracy and passionate professional development in teacher-leaders. Cambridge Journal of Education, 48(5), 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, C., & Rubie-Davies, C. (2022). Middle leadership practices in secondary schools associated with improved student outcomes. School Leadership & Management, 42(5), 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsyuruba, B., Arghash, N., & Basch, J. (2024). Flourishing among Canada’s outstanding principal award recipients: The critical role of resilience. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lai, T. H., & Huang, Y. P. (2022). I was a class leader: Exploring a Chinese English teacher’s negative emotions in leadership development in Taiwan. English Teaching & Learning, 46, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lambert, S. (2020). Emotional awareness amongst middle leadership. Journal of Work Applied Management, 12(2), 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lambert, S. (2022). The practical application on middle leaders of performing coaching interventions on others. Management in Education, 39(1), 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K., Buckley-Walker, K., & Tindall-Ford, S. (2023). Middle leaders’ facilitation of teacher learning in collaborative teams. School Leadership & Management, 43(3), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K., Grice, C., Tindall-Ford, S., & De Nobile, J. (2020a). Middle leading in Australian schools: Professional standards, positions, and professional development. School Leadership & Management, 40(5), 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K., Tindall-Ford, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2020b). Middle leading and influence in two Australian schools. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 48(6), 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K., Tindall-Ford, S., & Lamanna, J. (2021). School middle leadership: Systematic review. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Loughland, T., & Ryan, M. (2022). Beyond the measures: The antecedents of teacher collective efficacy in professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 48(2), 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2002). Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) user’s manual. Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, F., Ho, C. S. M., Lipscombe, K., & Bryant, D. (2024). Principals engaging middle leaders in school improvement: Case studies from New Zealand and Hong Kong. Leading & Managing, 30(2), 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher, 13(5), 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Reprint-preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New South Wales Department of Education (NSWDoE). (2024). Middle leaders. Available online: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/school-leadership-institute/sli-stories-/middle-leaders-and-the-sli (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Park, S., Hironaka, S., Carver, P., & Nordstrum, L. (2013). Continuous improvement in education. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Available online: https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/carnegie-foundation_continuous-improvement_2013.05.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Petrides, K. V. (2009). Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). In C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske, & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 85–101). Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., Furnham, A., & Mavroveli, S. (2007). Trait emotional intelligence: Moving forward in the field of EI. Emotional Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns, 4, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Pettigrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, L. M., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme (1st ed.). Lancaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P. A., & Zembylas, M. (2009). Introduction to advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives. In P. Schutz, & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advances in teacher emotion research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Shaked, H. (2024). Enabling factors of instructional leadership in subject coordinators. Journal of Educational Administration, 62(2), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J., Bryant, D. A., & Walker, A. D. (2022). School middle leaders as instructional leaders: Building the knowledge base of instruction-oriented middle leadership. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(5), 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Wong, C.-S., Wong, P.-M., & Peng, K. Z. (2010). Effect of middle-level leader and teacher emotional intelligence on school teachers’ job satisfaction: The case of Hong Kong. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 38(1), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D., & Chen, J. (2023). Emotional well-being and performance of middle leaders: The role of organisational trust in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Administration, 61(6), 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Self-Awareness Emotional Self-awareness Self Confidence Accurate Self-Assessment | Social Awareness Empathy Organizational Awareness Service Orientation |

| Self-Management Self-Control Initiative Transparency Adaptability Achievement Drive | Relationship Management Developing Others Influence Inspirational Leadership Teamwork and Collaboration Change Catalyst Conflict Management Building Bonds |

| Search Terms “Emotional intelligence” OR “Social intelligence “OR “Self-awareness” OR “Social awareness” OR “Self-management” or “Self-regulation” OR “Relationship management” OR “Empathy” Or “Emotion*” | |

| AND “Teacher leader*” OR “Head teacher*” OR “Middle leader*” OR “Head of department*” OR “Subject leader*” OR “Team leader*” OR “Co-ordinator*” | |

| AND “School*” | |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Empirical journal articles written in English. January 2000–2025 Educational Research Research explicit to ML SEI and/or findings explicit to school middle leadership | Unpublished research Editorials Theses or dissertations Non-English publications Not an explicit focus on school middle leaders or teacher leaders’ social emotional intelligence |

| Participant Name (Pseudonym) | Middle Leadership Position | School Sector | School Type | Years of Experience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching | Middle Leadership | ||||

| Adam | Assistant Principal Curriculum and Instruction (APC&I) | Public | Primary | 16 | 10 |

| Brad | Head of Year 9 Pastoral Care | Independent | Secondary | 14 | 4 |

| Craig | Assistant Principal Stage 1 | Public | Primary | 13 | 5 |

| Diane | Assistant Principal Curriculum and Instruction (APC&I) | Public | Primary | 19 | 5 |

| Eva | Assistant Principal | Public | Primary | 14 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tindall-Ford, S.; Lipscombe, K. Middle Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence: A Scoping Review and Empirical Exploration. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081047

Tindall-Ford S, Lipscombe K. Middle Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence: A Scoping Review and Empirical Exploration. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081047

Chicago/Turabian StyleTindall-Ford, Sharon, and Kylie Lipscombe. 2025. "Middle Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence: A Scoping Review and Empirical Exploration" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081047

APA StyleTindall-Ford, S., & Lipscombe, K. (2025). Middle Leadership and Social Emotional Intelligence: A Scoping Review and Empirical Exploration. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081047