Strategies Employed by Mexican Secondary School Students When Facing Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Acquisition of Academic Vocabulary

3. Strategies for the Acquisition and Teaching of Academic Vocabulary

4. The Present Study

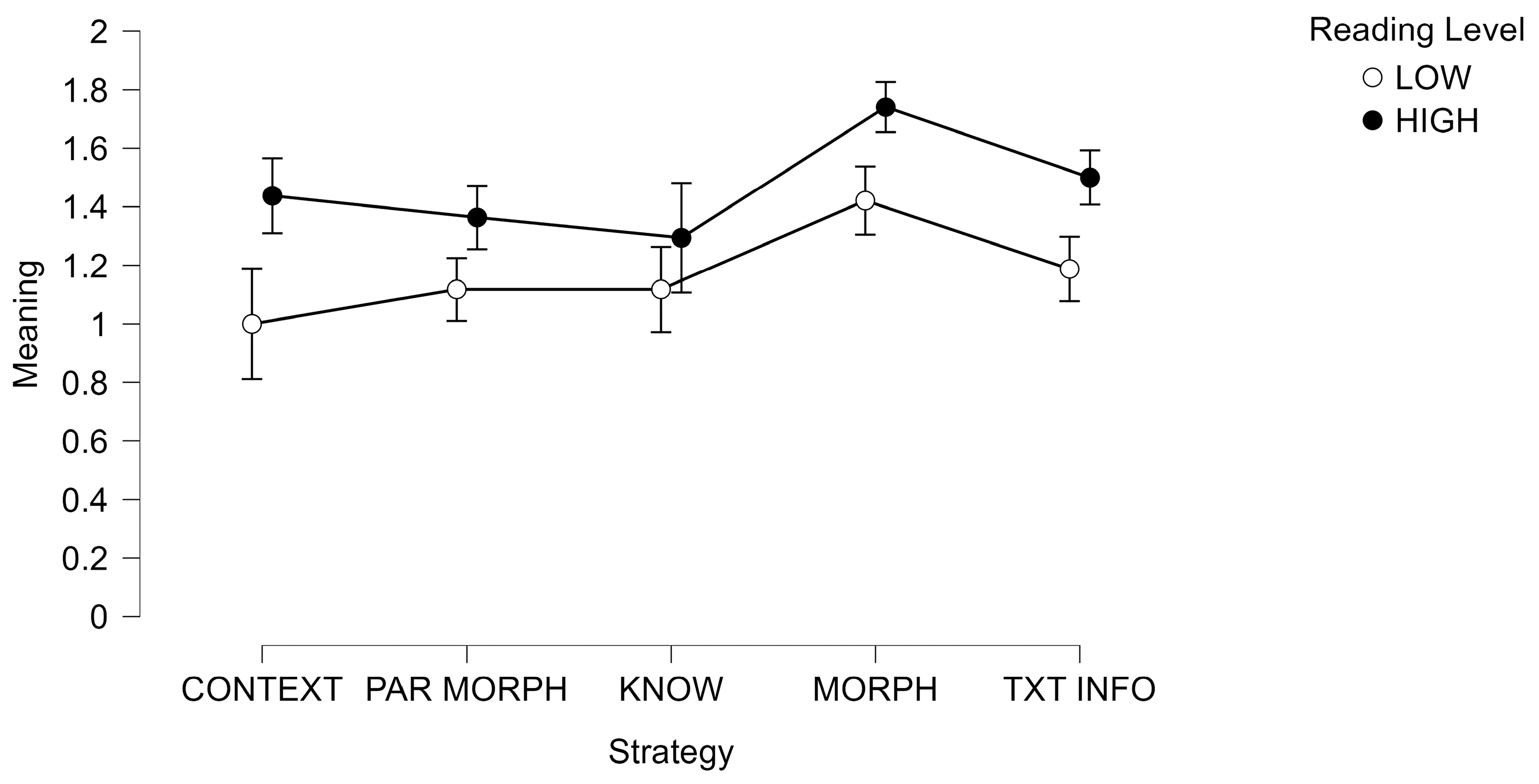

- Research Question 1: What strategies do Mexican secondary school students with high and low levels of reading comprehension use when encountering unfamiliar academic vocabulary?

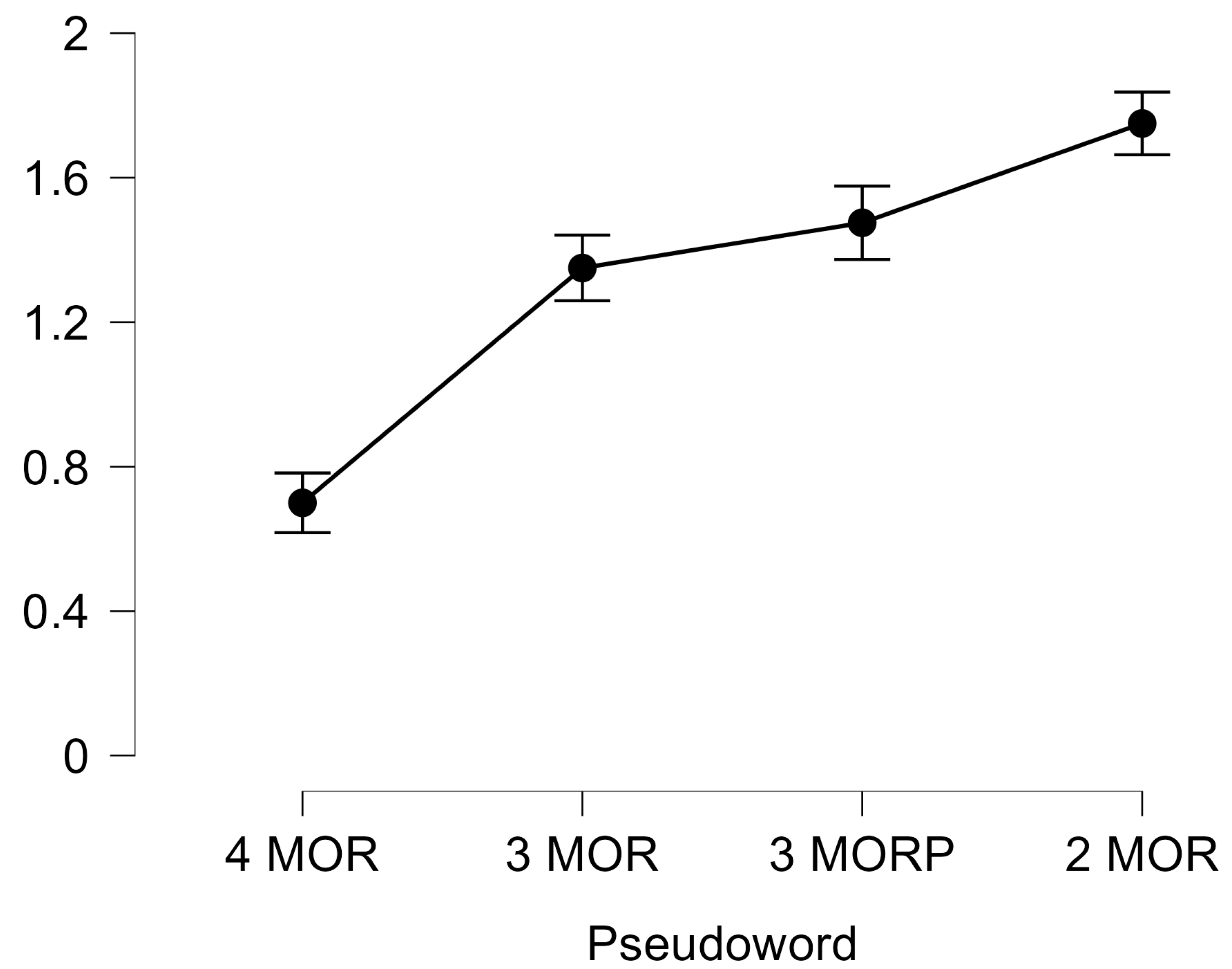

- Research Question 2: Do the strategies used by the students enable them to access the meaning of unfamiliar academic vocabulary, and which strategy is more effective?

- Research Question 3: Does the type of strategies students employ to access unfamiliar academic vocabulary depend on their level of reading comprehension, and if so, how is this influence manifested?

5. Materials and Method

5.1. Participants

5.2. Instruments

5.2.1. Instrument for Measuring Reading Comprehension

5.2.2. Instrument for Measuring Access to Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary

5.3. Procedure

5.4. Transcription and Coding

6. Results

6.1. Results of the Analysis of Strategies Employed by Students to Access the Meaning of Unfamiliar Words

6.2. Results of the Analysis of Access to the Meaning of Unfamiliar Words

7. Discussion

7.1. Research Question #1

7.2. Research Question #2

7.3. Research Question #3

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Texts A

En reuniones virtuales, apaga la cámaraMartha Duhne

Los efectos de la música en el cerebroMartha Duhne

Appendix A.2. Texts B

En reuniones virtuales, apaga la cámaraMartha Duhne

Los efectos de la música en el cerebroMartha Duhne

References

- Alexander-Shea, A. (2011). Redefining vocabulary: The new learning strategy for social studies. The Social Studies, 102, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, J. M., Miller, G. A., & Wakefield, P. C. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(10), 1–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijos Uzho, A. P., Paucar Guayara, C. V., & Quintero Barberi, J. A. (2023). Estrategias para la comprensión lectora: Una revisión de estudios en Latinoamérica. Revista Andina de Educación, 6(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangs, K. E., & Binder, K. S. (2016). Morphological awareness intervention: Improving spelling, vocabulary, and reading comprehension for adult learners. Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education, 5(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baralo, M. (2007). Adquisición de palabras: Redes semánticas y léxicas. In C. Pastor (Coord.), Actas del programa de formación para Profesorado de español como lengua extranjera 2006–2007 (pp. 384–399). Instituto Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, J. F. (2009). Vocabulary and reading comprehension: The nexus of meaning. In S. E. Israel, & G. G. Duffy (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 323–334). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, J. F., Ware, D., & Edwards, E. C. (2007). “Bumping into spicy, tasty words that catch your tongue”: A formative experiment on vocabulary instruction. The Reading Teacher, 61(2), 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2008). Creating robust vocabulary: Frequently asked questions and extended examples. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovska, N. (2024). Socioculturally-informed vocabulary pedagogy: Incorporating mediational tools to enhance vocabulary instruction. Language Teaching, 57(4), 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, P. N., Kirby, J. R., & Deacon, S. H. (2010). The effects of morphological instruction on literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 144–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabadas, M., & García Valenzuela, L. (2023, December 6). ¿Te animas a hacer la prueba PISA? Aquí puedes consultarla y resolverla. El Universal. Available online: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/te-animas-a-hacer-la-prueba-pisa-aqui-puedes-consultarla-y-resolverla/ (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Carlisle, J. F. (2004). Morphological processes that influence learning to read. In C. A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, & K. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy (pp. 318–339). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional para la Mejora Continua de la Educación. (2023). Evaluación diagnóstica del aprendizaje de las y los alumnos de educación básica 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.mejoredu.gob.mx/images/Informe_diagnostica.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). (2016). International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ¿Cómo ves? Divulgación de la ciencia UNAM. (2024, April 24). Ráfagas. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Available online: https://www.comoves.unam.mx/numeros (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- De Freitas, P. V., Mota, M. M., & Deacon, S. H. (2018). Morphological awareness, word reading, and reading comprehension in Portuguese. Applied Psycholinguistics, 39(3), 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diccionario del Español de México (DEM). (2024, April 24). El Colegio de México, A. C. Available online: https://www.colmex.mx/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Godínez, E. M., & Alarcón, L. J. (2018). El léxico especializado como expresión de la competencia discursiva académica en ensayos producidos por jóvenes escolarizados en una clase de literatura. In C. Bazerman, D. Russell, & P. Rogers (Eds.), Conocer la escritura: Investigación más allá de las fronteras (pp. 155–179). Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, A. P., Petscher, Y., Carlisle, J. F., & Mitchell, A. M. (2017). Exploring the dimensionality of morphological knowledge for adolescent readers. Journal of Research in Reading, 40(1), 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez de Silva, G. (1998). Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua española. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hess Zimmermann, K. (2013). Desarrollo léxico en la adolescencia: Un análisis de sustantivos en narraciones orales y escritas. Actualidades en Psicología, 27(115), 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess Zimmermann, K. (2019). Pensar sobre la morfología de las palabras: Un proyecto didáctico para el desarrollo de vocabulario en la escuela secundaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 12(2), 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess Zimmermann, K., & Núñez Rodríguez Wyler, M. A. (2021). Reproducibilidad de un proyecto didáctico para la adquisición de vocabulario académico en estudiantes de secundaria. Saberes y Prácticas: Revista de Filosofía y Educación, 6(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, E. (2014). Language development. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Ilter, I. (2019). The efficacy of context clue strategy instruction on middle grades students’ vocabulary development. RMLE Online, 42(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (INEE). (2017). El aprendizaje de los alumnos de tercero de secundaria en México. INEE. [Google Scholar]

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). (2022). Two years after: Saving a generation. The World Bank—UNICEF—UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Kärbla, T., Uibu, K., & Männamaa, M. (2020). Teaching strategies to improve students’ vocabulary and text comprehension. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M. J., & Lesaux, N. K. (2007). Breaking down words to build meaning: Morphology, vocabulary, and reading comprehension in the urban classroom. The Reading Teacher, 61(2), 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M. J., & Lesaux, N. K. (2012). Effects of academic language instruction on relational and syntactic aspects of morphological awareness for sixth graders from linguistically diverse backgrounds. The Elementary School Journal, 112(3), 519–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, R., Ben-Zvi, G., & Ravid, D. (2016). Morpho-lexical development in language impaired and typically developing Hebrew-speaking children from two SES backgrounds. Reading and Writing, 30(5), 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lions, S., & Peña, M. (2016). Reading comprehension in Latin America: Difficulties and possible interventions. In D. D. Preiss (Ed.), Child and adolescent development in Latin America. New directions for child and adolescent development (pp. 71–84). Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llauradó, A., & Tolchinsky, L. (2013). Growth of text-embedded lexicon in Catalan: From childhood to adolescence. First Language, 33(6), 628–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens Tatay, A. C., Gil Pelluch, L., Vidal-Abarca Gámez, E., Martínez Giménez, T., Mañá Lloriá, A., & Gilabert Pérez, R. (2011). Prueba de competencia lectora para educación secundaria (CompLEC). Psicothema, 23(4), 808–817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mancilla-Martinez, J., & Lesaux, N. K. (2011). Early home language use and later vocabulary development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D., Colenbrander, D., Inoue, T., & Georgiou, G. K. (2024). How well do schoolchildren and adolescents know the form and meaning of different derivational suffixes? Evidence from a cross-sectional study. Applied Psycholinguistics, 45(2), 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Vegas, R. A. (2018). Modelos de aprendizaje léxico basados en la morfología derivativa. Revista de Filología Hispánica, 34(1), 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno de Alba, J. G. (1986). Morfología derivativa nominal en el español de México. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Muraki, E. J., Reggin, L. D., Feddema, C. Y., & Pexman, P. M. (2023). The development of abstract word meanings. Journal of Child Language, 52, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A., Franklin, S., Breen, A., Hanlon, M., McNamara, A., Bogue, A., & James, E. (2017). A whole class teaching approach to improve the vocabulary skills of adolescents attending mainstream secondary school in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 33(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, W., & Townsend, D. (2012). Words as tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, W. D., Rupley, W. H., Blair, T. R., & Wood, K. D. (2015). Vocabulary strategies for linguistically diverse learners. Middle School Journal, 39(3), 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippold, M. A. (2016). Later language development: School-age children, adolescents, and young adults. PRO-ED. [Google Scholar]

- Nippold, M. A., & Sun, L. (2008). Knowledge of morphologically complex words: A developmental study of older children and young adolescents. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugraha, K. N. (2017). Vocabulary learning strategies used by junior high school students. Indonesian Journal of English Language Studies, 3(2), 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i_53f23881-en.html (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Pacheco, M. B., & Goodwin, A. P. (2013). Putting two and two together: Middle school students’ morphological problem-solving strategies for unknown words. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(7), 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelluch, L. G., Vidal-Abarca, E. G., Martínez, G. T., Mañá, L. A., Gilabert, P. R., & Cerdán, R. (2008). Prueba de competencia lectora para educación secundaria. Ministerio de Educación, Política Social y Deporte. [Google Scholar]

- Ravid, D., & Geiger, V. (2009). Promoting morphological awareness in Hebrew-speaking grade-schoolers: An intervention study using linguistic humor. First Language, 29(1), 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. (n.d.). Diccionario de la lengua española. Available online: https://dle.rae.es (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Real Academia Española, & Consejo General del Poder Judicial. (n.d.). Diccionario panhispánico del español jurídico. Available online: https://dpej.rae.es (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Rojas Porras, M. (2006). Esbozo de lineamientos conceptuales para la enseñanza y aprendizaje del léxico. Revista Educación, 30(2), 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D., Hairrell, A., Edmonds, M., Vaughn, S., Larsen, R., Willson, V., Rupley, W., & Byrns, G. (2010). A comparison of multiple-strategy methods: Effects on fourth-grade students’ general and content-specific reading comprehension and vocabulary development. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 3(2), 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson, & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112–133). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, I. (2007). Estrategias de lectura. Graó. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, E., & Deacon, S. H. (2015). Morphological awareness and morphological acquisition: A longitudinal examination of their relationship in English-speaking children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S. A. (1999). Vocabulary development. Brookline Books. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S. A., & Shiel, T. G. (1992). Teaching meaning vocabulary: Productive approaches for poor readers. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. John, P., & Vance, M. (2014). Evaluation of a principled approach to vocabulary learning in mainstream classes. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 30(3), 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, E. L., & Binder, K. S. (2015). An investigation of morphological awareness and processing in adults with low literacy. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(2), 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tighe, E. L., & Fernandes, M. A. (2019). Unraveling the complexity of the relations of metalinguistic skills to word reading with struggling adult readers: Shared, independent, and interactive effects. Applied Psycholinguistics, 40, 765–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolchinsky, L., & Berman, R. A. (2023). Growing into language: Developmental trajectories and neural underpinnings. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. (2001). World Medical Association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 79(4), 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T. S., & Cervetti, G. N. (2016). A systematic review of the research on vocabulary instruction that impacts text comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 52(2), 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiers, J. (2008). Building academic language: Essential practices for content classrooms. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Strategy | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual abstraction (CONTEXT) | Identifies and states the definition of the word as provided by the text | Justo después de eso [actigasicuantición] ya dice que es la cantidad de gases y compuestos de efecto invernadero que implica la fabricación o el consumo de bienes y servicios. Right after that [actigasicuantición], it says that it is the amount of greenhouse gases and compounds involved in the manufacture or consumption of goods and services. |

| Retrieving textual information (TXT INFO) | Repeats parts of the text that are not directly related to the meaning of the word | Después de esa palabra [actigasicuantición], la huella hídrica y la huella de tierra de una hora de videoconferencia con la cámara prendida, o sea, están proyectando algo desde una cámara. Bueno, esa fue la idea. After that word [actigasicuantición], the water footprint and land footprint of an hour of videoconferencing with the camera on, that is, they are projecting something from a camera. Well, that was the idea. |

| Morphological analysis (MORPH) | Identifies the morphemes of the word and constructs its meaning based on them | Neuro como de neurona que se encuentra en el cerebro y flexitud como flexibilidad y podría ser neurona- flexibilidad y puede ser que se vuelve flexible a las ciertas cosas. Neuro as in neuron, which is found in the brain, and flexitud like flexibility—so it could mean something like neuron-flexibility, and maybe it refers to becoming flexible to certain things. |

| Relating to prior knowledge (KNOW) | Connects to prior knowledge of content that is not present in the text | Suena como una palabra científica, por su nombre parece venir como del latín por actigas. It sounds like a scientific word, as its name seems to come from the Latin actigas. |

| Partial retrieval of morphemes (PAR MORPH) | Retrieves or cites part of the word but does not succeed in fully determining its meaning | Porque cuantición es como cuántico y lo de actigas la palabra gas, eso sí está correcto, dice la cantidad de gases. Because cuantición sounds like quantum, and actigas includes the word gas—which makes sense, since it does mention the amount of gases. |

| Rereading the text multiple times (REREAD) | Reads the text or sentence two or more times | Volver a leer varias veces el texto. Rereading the text multiple times. |

| Type of Answer | Description | Example | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Retrieves the full meaning from the context within the text | Por lo que leí, pues la cantidad de gases que se liberan por la transmisión o las cámaras prendidas Based on what I read, it’s the amount of gases released through transmission or when the cameras are on | 2 |

| B | Retrieves the full meaning based on one or more morphemes of the word | Creo que tiene algo que ver con favorecer I think it has something to do with favoring | 2 |

| C | Retrieves the full meaning based on prior knowledge of content that is not present in the text | Como que son como las neuronas que se esparcen en todo el cerebro y te ayudan a aprenderte cosas… es como el trabajo de las neuronas It’s kind of like the neurons that spread throughout the brain and help you learn things… it’s like the work that neurons do | 2 |

| D | Retrieves the full meaning based on a synonym | Supongo que hace referencia a beneficiar a alguien o algo I guess it refers to benefiting someone or something | 2 |

| A2 | Retrieves partial meaning from the context within the text | Significa que las neuronas son más rápidas con la música porque tienen que pensar más rápido It means that neurons are faster with music because they have to think more quickly | 1 |

| B2 | Retrieves partial meaning based on one or more morphemes of the word | Es como uno de, así como dice aquí, del dióxido de carbono [gas], más o menos así. Algo de cuántico y gases, gas cuántico It’s like one of those—like it says here—carbon dioxide [gas], something like that. Something about quantum and gases, quantum gas | 1 |

| C2 | Retrieves partial meaning based on prior knowledge of content that is not present in the text | Pues yo creo que significa como el daño que hace a algo o el efecto que tiene en una persona o en un ambiente Well, I think it means something like the harm it causes to something, or the effect it has on a person or the environment | 1 |

| E | Does not retrieve the meaning | No sé muy bien qué significa I’m not quite sure what it means | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hess Zimmermann, K.; Hernández Arriola, M.G.; Avecilla-Ramírez, G.N. Strategies Employed by Mexican Secondary School Students When Facing Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070917

Hess Zimmermann K, Hernández Arriola MG, Avecilla-Ramírez GN. Strategies Employed by Mexican Secondary School Students When Facing Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070917

Chicago/Turabian StyleHess Zimmermann, Karina, María Guadalupe Hernández Arriola, and Gloria Nélida Avecilla-Ramírez. 2025. "Strategies Employed by Mexican Secondary School Students When Facing Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070917

APA StyleHess Zimmermann, K., Hernández Arriola, M. G., & Avecilla-Ramírez, G. N. (2025). Strategies Employed by Mexican Secondary School Students When Facing Unfamiliar Academic Vocabulary. Education Sciences, 15(7), 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070917