Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher- and School-Level Predictors in Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

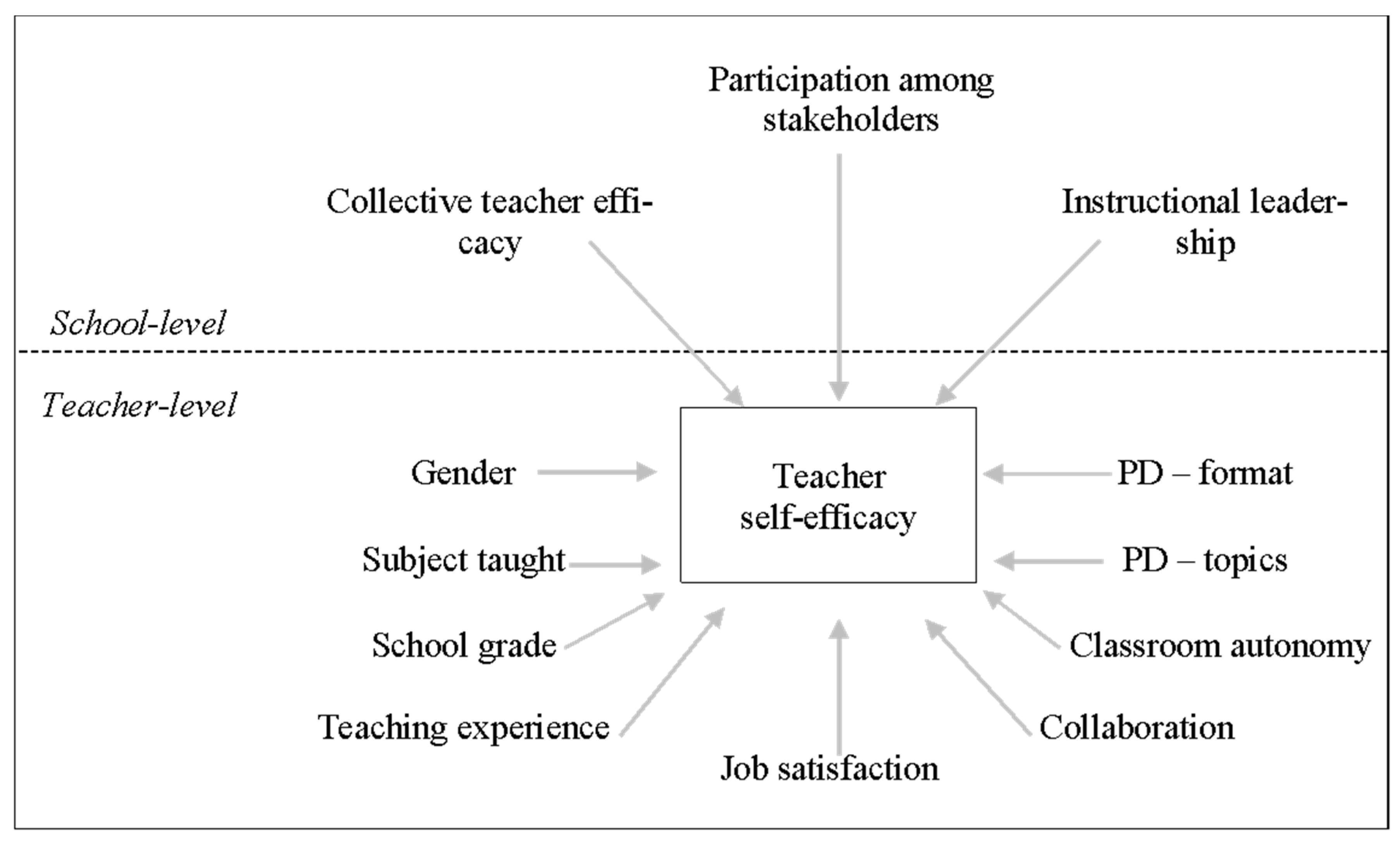

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.2. Collective Teacher Efficacy

2.3. Teacher Self-Efficacy Predictors

2.3.1. Teacher-Level Variables

2.3.2. School-Level Variables

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.1.1. Sample 1

3.1.2. Sample 2

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Teacher-Level Variables

School-Level Factors

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

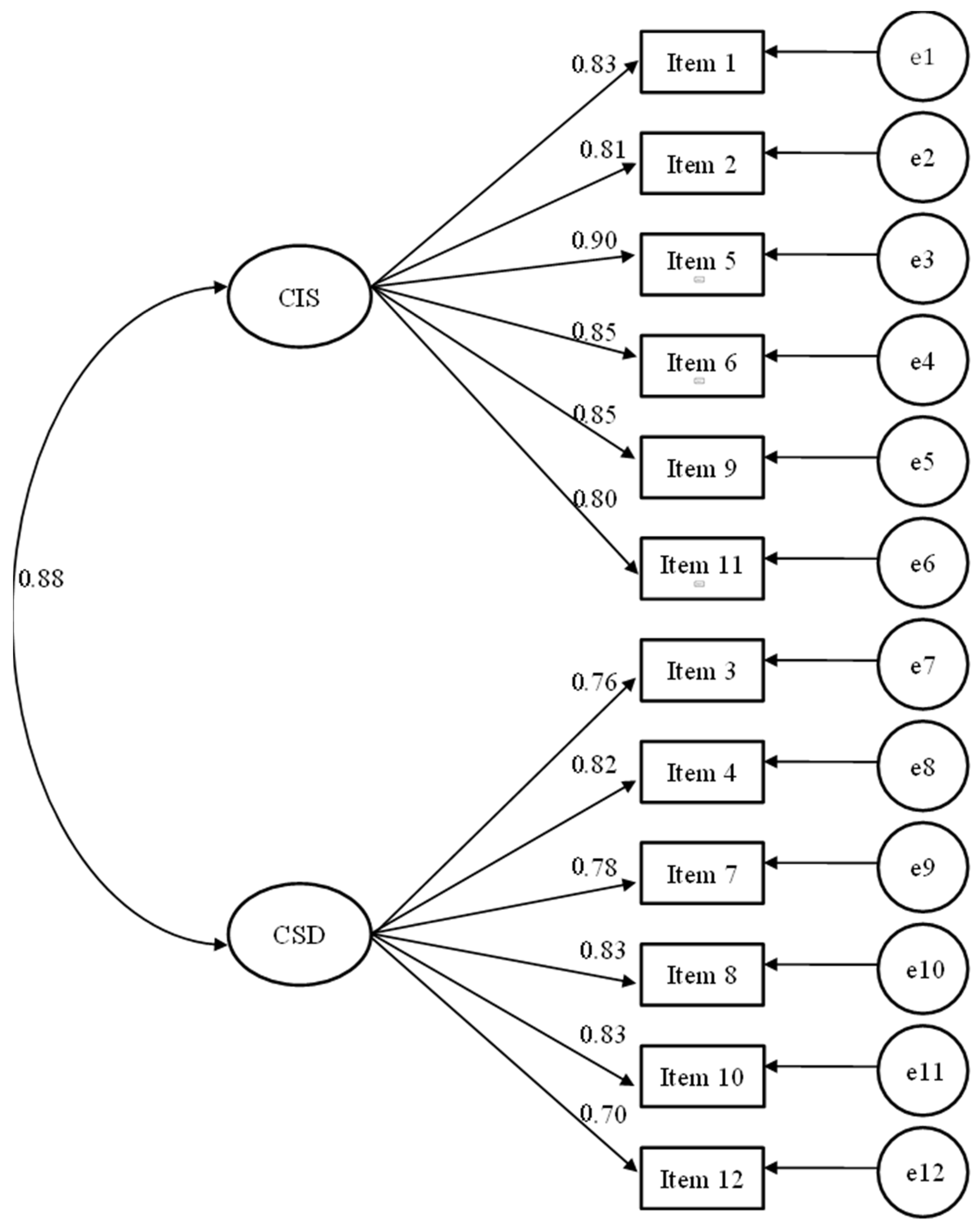

4.1. Psychometric Properties of the CTBS

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analyses2

4.3. Multilevel Analyses

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scales Used to Measure the Independent Variables

Appendix B. Sample-Size Estimation and Post Hoc Power Analysis

Appendix B.1. Sample-Size Estimation

Appendix B.2. Post Hoc Power Analysis

Appendix C. Spanish Version of the Collective Teacher Beliefs Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Nada/En absoluto | Muy poco | Algo/En alguna medida | Bastante | Mucho/Muy bien |

| Nada/En absoluto | Muy poco | Algo/En alguna medida | Bastante | Mucho/Muy bien | |||||

| ¿Cuánto pueden hacer los profesores de tu centro para producir un aprendizaje significativo en los alumnos? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto puede hacer tu centro para que los alumnos se crean capaces de realizar con éxito sus tareas escolares? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿En qué medida los profesores de tu centro pueden dejar claras sus expectativas respecto al comportamiento adecuado de los alumnos? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿En qué medida el personal de tu centro puede establecer normas y procedimientos que faciliten el aprendizaje? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto pueden hacer los profesores de tu centro para ayudar a los alumnos a dominar contenidos complejos? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto pueden hacer los profesores de tu centro para promover la comprensión profunda de conceptos académicos? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Hasta qué punto los profesores de tu centro pueden responder adecuadamente ante alumnos que tienen una conducta desafiante? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto puede hacer el personal de tu centro para controlar el comportamiento disruptivo? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto pueden hacer los profesores de tu centro para ayudar a los alumnos a pensar críticamente? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Hasta qué punto los adultos de tu centro pueden lograr que los alumnos cumplan las normas? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto puede hacer tu centro para fomentar la creatividad de los alumnos? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| ¿Cuánto puede hacer tu centro para que los alumnos se sientan seguros? | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | ⑧ | ⑨ |

| 1 | We used McDonald’s Omega when referring to results from the TALIS study, as this is the reliability estimate reported in their documentation. For the rest of our analyses, we reported Cronbach’s Alpha, given that we had access to the item-level data and followed standard practice in similar studies. Our intention was to remain consistent with the sources cited and transparent in our reporting. |

| 2 | The descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and HLM models were tested with data from Sample 2. |

References

- Ainley, J., & Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and learning international survey (TALIS) 2018 conceptual framework (OECD Education Working Papers, Issue 187). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanoglu, M. (2021). The role of instructional leadership in increasing teacher self-efficacy: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M., Visentin, D. C., Thapa, D. K., Hunt, G. E., Watson, R., & Cleary, M. (2020). Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(9), 2209–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2016). Teachers’ views of their school climate and its relationship with teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Learning Environments Research, 19, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armor, D., Conroy-Oseguera, P., Cox, M., King, N., McDonnell, L., Pascal, A., Pauly, E., & Zellman, G. (1976). Analysis of the school preferred reading programs in selected Los Angeles minority schools. NRIC. [Google Scholar]

- Backhoff Escudero, E., & Pérez-Morán, J. C. (2015). Segundo estudio internacional sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje (TALIS 2013). Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Taştan, S., Davoudi, S. M. M., Masalimova, A. R., Bersanov, A. S., Kurbanov, R. A., Boiarchuk, A. V., & Pavlushin, A. A. (2018). The impacts of teacher’s efficacy and motivation on student’s academic achievement in science education among secondary and high school students. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(6), 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. American Psychological Association, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Quantitative methods in psychology: Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. A., & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 361–379). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burić, I., & Kim, L. E. (2020). Teacher self-efficacy, instructional quality, and student motivational beliefs: An analysis using multilevel structural equation modeling. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Job satisfaction predicts teacher self-efficacy and the association is invariant: Examinations using TALIS 2018 data and longitudinal Croatian data. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., & Moè, A. (2020). What makes teachers enthusiastic: The interplay of positive affect, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 89, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(2), 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., & Tang, R. (2021). School support for teacher innovation: Mediating effects of teacher self-efficacy and moderating effects of trust. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansoy, R., Parlar, H., & Polatcan, M. (2020). Collective teacher efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between instructional leadership and teacher commitment. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(6), 900–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Steca, P. (2003). Efficacy beliefs as determinants of teachers’ job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. (2006). Multilevel research. In E. R. Spangenberg, F. T. L. Leong, & J. T. Austin (Eds.), The psychology research handbook: A guide for graduate students and research assistants (pp. 401–418). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnut, S. R., & Burley, H. (2015). Self-efficacy as a predictor of commitment to the teaching profession: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., & Mao, X. (2021). Teacher autonomy for improving teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms: A cross-national study of professional development in multicultural education. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalik, T., Sezgin, F., Kavgaci, H., & Kilinç, A. C. (2012). Examination of relationships between instructional leadership of school principals and self-efficacy of teachers and collective teacher efficacy. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 12(4), 2498–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Çoban, Ö., Özdemir, N., & Bellibaş, M. S. (2020). Trust in principals, leaders’ focus on instruction, teacher collaboration, and teacher self-efficacy: Testing a multilevel mediation model. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 51(1), 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da’as, R., Qadach, M., Erdogan, U., Schwabsky, N., Schechter, C., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2021). Collective teacher efficacy beliefs: Testing measurement invariance using alignment optimization among four cultures. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(2), 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilekli, Y., & Tezci, E. (2020). A cross-cultural study: Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching thinking skills. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoo, J. (2017a). Collective efficacy: How educators’ beliefs impact student learning. Corwin. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Donohoo, J. (2017b). Collective teacher efficacy research: Implications for professional learning. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 2(2), 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyar, I., Gumus, S., & Bellibas, M. S. (2013). Multilevel analysis of teacher work attitudes: The influence of principal leadership and teacher collaboration. International Journal of Educational Management, 27(7), 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eells, R. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Loyola University. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Erdogan, U., Dipaola, M. F., & Donmez, B. (2022). School-level variables that enhance student achievement: Examining the role of collective teacher efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(7), 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fives, H., & Buehl, M. M. (2009). Examining the factor structure of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale. Journal of Experimental Education, 78(1), 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Torres, D. (2019). Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction in U.S. schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 79, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D. (1998). The effects of collective teacher efficacy on student achievement in urban public elementary schools. Ohio State University. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Goddard, R. D. (2002). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the measurement of collective efficacy: The development of a short form. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62(1), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., & Goddard, Y. (2001). A multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher and collective efficacy in urban schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., Goddard, Y., Sook Kim, E., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration, and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2004a). Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., LoGerfo, L., & Hoy, W. K. (2004b). High school accountability: The role of perceived collective efficacy. Educational Policy, 18(3), 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). A theoretical and empirical investigation of teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools. Teachers College Record, 109(4), 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Connor, C. M., Yang, Y., Roehrig, A. D., & Frederick, J. (2012). The effects of teacher qualification, teacher self-efficacy, and classroom practices on fifth graders’ literacy outcomes. The Elementary School Journal, 113(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Gümüş, E., & Bellibaş, M. S. (2021). The relationship between the types of professional development activities teachers participate in and their self-efficacy: A multi-country analysis. European Journal of Teacher Education, 46(1), 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajovsky, D. B., Chesnut, S. R., & Jensen, K. M. (2020). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 82, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallinger, P., Hosseingholizadeh, R., Hashemi, N., & Kouhsari, M. (2018). Do beliefs make a difference? Exploring how principal self-efficacy and instructional leadership impact teacher efficacy and commitment in Iran. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 46(5), 800–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Haverback, H. R., & McNary, S. (2015). Shedding light on preservice teachers’ domain-specific self-efficacy. The Teacher Educator, 50(4), 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseingholizadeh, R., Amrahi, A., & El-Farr, H. (2020). Instructional leadership, and teacher’s collective efficacy, commitment, and professional learning in primary schools: A mediation model. Professional Development in Education, 49(3), 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEE. (2019a). Informe de resultados PLANEA 2017. El aprendizaje de los alumnos de tercero de secundaria en México. Lenguaje y comunicación y matemáticas. Available online: https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/P1D321.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).[Green Version]

- INEE. (2019b). Informe de resultados PLANEA EMS 2017. El aprendizaje de los alumnos de educación media superior en México. Lenguaje y Comunicación y Matemáticas. Available online: https://historico.mejoredu.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/P1D320.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).[Green Version]

- INEE. (2019c). Panorama educativo de México. Indicadores del sistema educativo nacional 2018. Educación básica y media superior. Available online: https://www.inee.edu.mx/publicaciones/panorama-educativo-de-mexico-2018-educacion-basica-y-media-superior/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).[Green Version]

- Jak, S., & Jørgensen, T. D. (2017). Relating measurement invariance, cross-level invariance, and multilevel reliability. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasalak, G., & Dağyar, M. (2020). The relationship between teacher self-efficacy and teacher job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the teaching and learning international survey (TALIS). Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 20(3), 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R. M. (2010). Teacher stress: The mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. Journal of Educational Research, 103(5), 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(2), 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., Chong, W. H., Huan, V. S., Wong, I., Kates, A., & Hannok, W. (2008). Motivation beliefs of secondary school teachers in Canada and Singapore: A mixed methods study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(7), 1919–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickenberg, M., Kullmann, H., Wüthrich, S., Sahli Lozano, C., Loreman, T., Sharma, U., Avramidis, E., Subban, P., & Woodcock, S. (2025). Teachers’ collective efficacy with regard to inclusive practices-Characteristics of a new scale and analyses from Canada, Germany and Switzerland. Frontiers in Psychology 16, 1530689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koniewski, M. (2019). The teacher self-efficacy scale (TSES) factorial structure evidence review and new evidence from polish-speaking samples. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(6), 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, T., Duyar, I., & Çalik, T. (2011). Are we legitimate yet?: A closer look at the casual relationship mechanisms among principal leadership, teacher self-efficacy and collective efficacy. Journal of Management Development, 31(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. C. K., Zhang, Z., & Yin, H. (2011). A multilevel analysis of the impact of a professional learning community, faculty trust in colleagues and collective efficacy on teacher commitment to students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Qiang, F., & Kang, H. (2023). Distributed leadership, self-efficacy and wellbeing in schools: A study of relations among teachers in Shanghai. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Bellibaş, M. S., & Gümüş, S. (2020). The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 49, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Liao, W. (2019). Professional development and teacher efficacy: Evidence from the 2013 TALIS. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(4), 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A. (1969). What is job satisfaction? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4(4), 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K., & Trevethan, R. (2020). Efficacy perceptions of preservice and inservice teachers in China: Insights concerning culture and measurement. Frontiers of Education in China, 15(2), 332–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 1(3), 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrothanasis, K., Zervoudakis, K., & Xafakos, E. (2021). Secondary special education teachers’ beliefs towards their teaching self-efficacy. Preschool and Primary Education, 9(1), 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moè, A., Pazzaglia, F., & Ronconi, L. (2010). When being able is not enough. The combined value of positive affect and self-efficacy for job satisfaction in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, F. S., & Asadzadeh, H. (2012). Testing the mediating role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the relationship between sources of efficacy information and students achievement. Asia Pacific Education Review, 13, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojavezi, A., & Tamiz, M. P. (2012). The impact of teacher self-efficacy on the students’ motivation and achievement. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A., Mokhtar Maouloud, V., Kafayat Omowunmi, A., & Sahari bin Nordin, M. (2021). Teachers’ commitment, self-efficacy and job satisfaction as communicated by trained teachers. Management in Education, 37(3), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoge, M. J., & Challens, B. H. (2018). Perceived collective teacher efficacy in low performing schools. South African Journal of Education, 38(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninković, S., & Knežević-Florić, O. (2018). Validation of the serbian version of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale (TSES). Zbornik Instituta Za Pedagoska Istrazivanja, 50(1), 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019a). Strong foundations for quality and equity in mexican schools, implementing education policies. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019b). TALIS 2018 results (volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019c). TALIS 2018 technical report. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 results (volume II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals: Vol. II. TALIS. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L. (2020). The relationship between teacher leadership and collective teacher efficacy in Chinese upper secondary schools. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(2), 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H. N., & John, J. E. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching math: Relations with teacher and student outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozas, M., Gonzalez Trujillo, C. J., & Letzel, V. (2021). A change of perspective—Exploring Mexican primary and secondary school students’ perceptions of their teachers differentiated instructional practice. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 21(3), 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, L. (2007). Autoeficacia del profesor universitario: Eficacia percibida y práctica docente. Narcea. [Google Scholar]

- Prilop, C. N., Weber, K. E., Prins, F., & Kleinknecht, M. (2021). Connecting feedback to self-efficacy: Receiving and providing peer feedback in teacher education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeian, S., & Abdollahzadeh, E. (2020). Teacher efficacy and its correlates in the EFL context of Iran: The role of age, experience, and gender. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 7(4), 1533–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J. A., & Gray, P. (2006). Transformational leadership and teacher commitment to organizational values: The mediating effects of collective teacher efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rodriguez, F., & Lara, S. (2020). Mapeo sistemático de la literatura sobre la eficacia colectiva docente. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formacion Del Profesorado, 34(2), 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rodriguez, F., & Lara, S. (2023). Unpacking collective teacher efficacy in primary schools: Student achievement and professional development. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 22, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Rodriguez, F., Lara, S., & Martínez, M. (2021). Spanish version of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale: An adaptation and validation study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schechter, C., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2006). Teachers’ sense of collective efficacy: An international view. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(6), 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, P., Nambudiri, R., & Mishra, S. K. (2017). Teacher effectiveness through self-efficacy, collaboration and principal leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(4), 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selya, A. S., Rose, J. S., Dierker, L. C., Hedeker, D., & Mermelstein, R. J. (2012). A practical guide to calculating Cohen’s f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports, 114(1), 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2019). Teacher self-efficacy and collective teacher efficacy: Relations with perceived job resources and job demands, feeling of belonging, and teacher engagement. Creative Education, 10(7), 1400–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2021). Collective teacher culture: Exploring an elusive construct and its relations with teacher autonomy, belonging, and job satisfaction. Social Psychology of Education, 24(6), 1389–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, L. M., Yang, J. S., & Hancock, G. R. (2016). Construct meaning in multilevel settings. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 41(5), 481–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A., & Xia, J. (2018). Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. International Journal of Educational Research, 92, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Barr, M. (2004). Fostering student learning: The relationship of collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 3(3), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Chen, J. A. (2014). Focusing attention on beliefs about capability and knowledge in teachers’ professional development. In L. E. Martin, S. Kragler, D. J. Quatroche, K. L. Bauserman, & A. Hargreaves (Eds.), Handbook of professional development in education: Successful models and practices (pp. 246–264). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigilis, N., Koustelios, A., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2010). Psychometric properties of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale within the Greek educational context. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(2), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, M. E., Cansoy, R., & Parlar, H. (2021). Organisational socialisation and collective teacher efficacy: The mediating role of school collaborative culture. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 94(202), 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 751–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valckx, J., Vanderlinde, R., & Devos, G. (2020). Departmental PLCs in secondary schools: The importance of transformational leadership, teacher autonomy, and teachers’ self-efficacy. Educational Studies, 46(3), 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, M., Bonvin, P., & Benoit, V. (2020). Psychometric properties of the French version of the teachers’ sense of efficacy scale (TSES-12f). European Review of Applied Psychology, 70(3), 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T. E., Vaaland, G. S., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2019). Associations between observed patterns of classroom interactions and teacher wellbeing in lower secondary school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Hall, N. C., & Rahimi, S. (2015). Self-efficacy and causal attributions in teachers: Effects on burnout, job satisfaction, illness, and quitting intentions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, H., & Kitsantas, A. (2007). Teacher and collective efficacy beliefs as predictors of professional commitment. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(5), 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. H., Hoy, W. K., & Tarter, C. J. (2013). Enabling school structure, collective responsibility, and a culture of academic optimism: Toward a robust model of school performance in Taiwan. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, Y. F. (2020). Effects of school climate and teacher self-efficacy on job satisfaction of mostly STEM teachers: A structural multigroup invariance approach. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, Y. F., & Wardat, Y. (2024). Job satisfaction of mathematics teachers: An empirical investigation to quantify the contributions of teacher self-efficacy and teacher motivation to teach. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 36, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Yin, H. (2017). Effects of professional learning community and collective teacher efficacy on teacher involvement and support as well as student motivation and learning strategies. In R. McLean (Ed.), Life in schools and classrooms. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, concerns and prospects (Vol. 38, pp. 139–151). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | p | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor | 343.622 | 0.001 | 54 | 0.168 (0.151–0.185) | 0.058 | 0.854 | 0.821 |

| Two-factor | 269.481 | 0.001 | 53 | 0.147 (0.130–0.164) | 0.054 | 0.891 | 0.864 |

| Spanish CTBS | Original CTBS (Tschannen-Moran & Barr, 2004) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | |

| CTE | 8.09 | 0.38 | 8.18 | 0.53 | 7.10 | 0.46 |

| CIS | 8.15 | 0.41 | 8.23 | 0.5 | 7.10 | 0.44 |

| CSD | 8.03 | 0.37 | 8.11 | 0.64 | 7.13 | 0.52 |

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Skewness | Kurtosis | Shapiro–Wilk | α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | p | ||||||||

| Teacher-level variables (N = 162) | |||||||||

| Teacher self-efficacy | 8.11 | 0.68 | 8.17 | 0.83 | −1.3 | 6.08 | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.91 |

| Satisfaction with classroom autonomy | 3.44 | 0.51 | 3.6 | 0.6 | −1.27 | 4.64 | 0.9 | 0.001 | 0.77 |

| Collaboration | 3.86 | 0.8 | 3.88 | 1.13 | 0.46 | 2.9 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| Job satisfaction | 3.67 | 0.4 | 3.88 | 0.5 | −1.6 | 5.54 | 0.83 | 0.001 | 0.79 |

| School-level variables (N = 22) | |||||||||

| Collective teacher efficacy | 8.16 | 0.35 | 8.3 | 0.37 | −0.72 | 2.63 | 0.93 | 0.001 | 0.95 |

| Participation among stakeholders | 3.24 | 0.27 | 3.26 | 0.35 | −0.56 | 2.55 | 0.96 | 0.001 | 0.85 |

| Instructional leadership | 3.46 | 0.57 | 3.67 | 1 | −0.7 | 2.17 | 0.96 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teacher self-efficacy | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.12 | |||||||||

| 3. Subject taught | 0.02 | −0.01 | ||||||||

| 4. School grade | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.05 | |||||||

| 5. Teaching experience | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.002 | ||||||

| 6. Satisfaction with classroom autonomy | 0.44 *** | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | |||||

| 7. Collaboration | 0.38 *** | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.25 ** | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||||

| 8. Job satisfaction | 0.21 ** | 0.08 | −0.16 * | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.24 ** | 0.22 ** | |||

| 9. Collective teacher efficacy | 0.21 ** | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.24 ** | 0.17 * | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||

| 10. Participation among stakeholders | 0.26 *** | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.27 *** | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.72 *** | |

| 11. Instructional leadership | −0.02 | −0.28 *** | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.1 | −0.001 | −0.06 | 0.005 | −0.12 | 0.06 |

| Formats of PD | % | Correlation with TSE | PD Topics | % | Correlation with TSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courses/seminars attended in person | 78.4 | 0.04 | Knowledge and understanding of my subject | 80.9 | 0.11 |

| Online courses/seminars | 76 | 0.1 | Pedagogical competencies | 84 | 0.24 ** |

| Education conferences | 50.6 | 0.24 ** | Knowledge of the curriculum | 64.8 | 0.18 * |

| Qualification program | 17.3 | 0.05 | Student assessment practices | 75.9 | 0.23 ** |

| Visits to other schools | 20.4 | 0.12 | ICT skills for teaching | 85.2 | 0.11 |

| Visits to business premises | 12.3 | 0.1 | Classroom management | 72.8 | 0.12 |

| Observation and coaching | 63.6 | 0.19 * | School management | 34.6 | 0.13 |

| Participation in a network of teachers | 31.5 | 0.17 * | Approaches to individualized learning | 61.7 | 0.19 * |

| Reading professional literature | 46.3 | 0.09 | Teaching students with special needs | 42.6 | 0.12 |

| Teaching in a multicultural setting | 22.8 | 0.14 | |||

| Teaching cross-curricular skills | 67.3 | 0.21 ** | |||

| Analysis of student assessments | 73.5 | 0.18 * | |||

| Teacher-parent cooperation | 69.8 | 0.22 ** | |||

| Communicating with people from different cultures | 15.4 | 0.27 *** |

| Fixed Effects | Random Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | Variance (SE) | ||

| Intercept | 8.07 (0.08) | Between-schools | 0.08 (0.05) |

| Within-schools | 0.39 (0.05) | ||

| ICC | 0.16 (0.09) | ||

| AIC | 335.11 | ||

| BIC | 344.37 | ||

| Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Teacher-level predictors | ||||||

| Gender (female) | −0.23 (0.14) | |||||

| Subject taught (Math) | −0.02 (0.10) | |||||

| School grade | ||||||

| 5th grade | −0.16 (0.15) | |||||

| 6th grade | −0.04 (0.16) | |||||

| 7th grade | −0.37 (0.16) * | |||||

| 8th grade | −0.07 (0.15) | |||||

| Teaching experience | 0.01 (0.01) | |||||

| PD formats | ||||||

| Courses | 0.04 (0.13) | |||||

| Online courses | 0.16 (0.13) | |||||

| Conferences | 0.18 (0.12) | |||||

| Qualification program | −0.01 (0.14) | |||||

| School visit | 0.15 (0.13) | |||||

| Business visit | 0.07 (0.17) | |||||

| Coaching | 0.21 (0.11) | |||||

| Network | 0.13 (0.11) | |||||

| Literature | 0.08 (0.11) | |||||

| PD topics | ||||||

| Knowledge | −0.11 (0.16) | |||||

| Competencies | 0.26 (0.16) | |||||

| Curriculum | −0.01 (0.14) | |||||

| Assessment | 0.11 (0.15) | |||||

| ICT skills | 0.11 (0.16) | |||||

| Classroom management | −0.15 (0.14) | |||||

| School management | 0.1 (0.12) | |||||

| Individualized learning | 0.04 (0.13) | |||||

| Special needs | 0.06 (0.12) | |||||

| Multicultural settings | 0.00 (0.13) | |||||

| Cross-curricular skills | 0.03 (0.14) | |||||

| Assessment use | 0.09 (0.15) | |||||

| Parents | 0.14 (0.13) | |||||

| Multicultural communication | 0.36 (0.15) * | |||||

| Classroom autonomy | 0.55 (0.09) *** | |||||

| Collaboration | 0.29 (0.06) *** | |||||

| Job satisfaction | 0.05 (0.12) | |||||

| School-level predictors | ||||||

| Collective teacher efficacy | 0.61 (0.18) *** | |||||

| Participation stakeholders | 0.81 (0.25) *** | |||||

| Instructional leadership | 0.05 (0.12) | −0.01 (0.12) | ||||

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Wald χ2 (df) | 10.65 (7) | 20.63 (9) | 27.99 (14) | 85 (3) | 10.76 (2) | 10.64 (2) |

| p-value | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Between-school variance | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.03) |

| Within-school variance | 0.38 (0.05) | 0.36 (0.04) | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) |

| ICC | 0.18 (0.09) | 0.20 (0.09) | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.21 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.07) |

| AIC | 360.62 | 354.39 | 366.94 | 281.81 | 333.27 | 332.72 |

| BIC | 391.50 | 391.44 | 419.43 | 300.34 | 348.71 | 348.15 |

| Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7 | Effect Size | Model 8 | Effect Size | |

| Teacher-level predictors | ||||

| Multicultural communication | 0.28 (0.12) * | 0.03 | 0.27 (0.12) * | 0.03 |

| Classroom autonomy | 0.54 (0.08) *** | 0.30 | 0.54 (0.08) *** | 0.30 |

| Collaboration | 0.25 (0.05) *** | 0.15 | 0.24 (0.06) *** | 0.15 |

| School-level predictors | ||||

| Collective teacher efficacy | 0.46 (0.16) ** | 0.003 | ||

| Participation stakeholders | 0.55 (0.23) * | 0.001 | ||

| R2 | 0.38 | 0.39 | ||

| Wald χ2 (df) | 103.69 (4) | 100.90 (4) | ||

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Between-school variance | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.03) | ||

| Within-school variance | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.25 (0.03) | ||

| ICC | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.16 (0.09) | ||

| AIC | 273.20 | 274.12 | ||

| BIC | 294.81 | 295.73 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salas-Rodriguez, F.; Lara, S.; Martínez, M. Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher- and School-Level Predictors in Mexico. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070913

Salas-Rodriguez F, Lara S, Martínez M. Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher- and School-Level Predictors in Mexico. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):913. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070913

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalas-Rodriguez, Fatima, Sonia Lara, and Martín Martínez. 2025. "Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher- and School-Level Predictors in Mexico" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070913

APA StyleSalas-Rodriguez, F., Lara, S., & Martínez, M. (2025). Teacher Efficacy Beliefs: A Multilevel Analysis of Teacher- and School-Level Predictors in Mexico. Education Sciences, 15(7), 913. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070913