1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

In K-12 settings, school leadership is imperative for setting the vision, culture, and operational success of a school (

Leithwood & Sun, 2018;

Leonor, 2021;

Murphy, 2015;

Torres, 2022). Strong principal leadership positively impacts school outcomes, either indirectly or directly, including student achievement, teacher morale, and parental involvement (

Hallinger & Murphy, 1985;

Leithwood & Sun, 2018;

Torres, 2022).

Leithwood and Sun (

2018) asserted that school leadership could influence student achievement both through direct paths and indirectly by shaping organizational conditions, such as teacher working conditions and school culture. Principals play a central role by establishing the overall direction and creating an environment that supports both teaching and learning. Their actions heavily influence the school’s organizational climate and directly affect how teachers perceive their working environment and how parents participate in student learning.

Teachers are the ones who directly experience and interpret the leadership practices of principals and other administrators. Teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of principal leadership are essential, as they are at the front line of implementing policies and practices that directly impact students (

Grissom & Loeb, 2011;

Hallinger & Heck, 1998;

Leithwood & Sun, 2012). When teachers feel supported and perceive the leadership as effective, they are more likely to be motivated, collaborate, and maintain high expectations for students, all of which contribute to better student outcomes (e.g.,

Leithwood et al., 2020a). Both principals’ and teachers’ perspectives on principal leadership shape the overall perception of school leadership, influencing the school panoramically, especially aspects such as teachers’ occupational well-being, job satisfaction, motivation, and parents’ engagement, which in turn impacts student success (

Hallinger & Heck, 2010;

Leithwood et al., 2020b;

Liebowitz & Porter, 2019).

Leithwood et al. (

2020b) emphasized that school leadership was a significant contributor to positive student outcomes, but also teacher outcomes. Not least,

Liebowitz and Porter (

2019) indicated that principal leadership behaviors directly affected teacher motivation and parental engagement. Therefore, understanding and aligning these perceptions are vital for achieving a cohesive and effective school environment.

1.2. Research Gaps

The impact of principal leadership has been extensively studied in K-12 educational settings and is proven to be a significant contributor to positive student outcomes in different geographical locations and across time. It is worth noting that existing literature confirmed that principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of school leadership were significantly different (

Day & Sammons, 2016;

Hallinger & Heck, 1998,

2010;

Leithwood & Day, 2007;

Leithwood & Jantzi, 2000;

Tan, 2024). First of all, much of the existing literature heavily focuses on how different leadership styles impact school-related variables and student performance (e.g.,

Bush & Glover, 2014;

Grissom & Loeb, 2020;

Hallinger, 2003;

Leithwood & Jantzi, 2000;

Grissom & Loeb, 2020). However, the relational dynamics between principals and teachers and how differing perceptions between these groups influence things such as parental involvement and student outcomes have been long overlooked (

Gordon & Seashore Louis, 2009;

Price, 2012;

Sebastian et al., 2016). Furthermore, the methodological challenge has been another contributing factor to the scarcity of such comparative studies, in that these studies require very complicated methodologies to accurately and robustly analyze the distinct perspectives of principals and teachers (

Hallinger & Heck, 2010;

Sun & Leithwood, 2015). For instance,

Grissom and Loeb (

2011) claimed that triangulating perceptions from different educational stakeholders, such as principals, teachers, and parents, posed significant methodological hurdles to such research because it is very challenging to gather data from different sources while ensuring reliability and validity. Moreover, the availability of comprehensive datasets that encompass both principals’ and teachers’ perceptions that enable educational researchers to make side-by-side comparisons, along with corresponding parental engagement measures and student achievement, turns out to be very challenging (

Grissom et al., 2015;

Hallinger, 2018;

Leithwood et al., 2020b).

1.3. Purpose of the Study

This study aims to assess the differences between principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of school leadership and examine how their differing perceptions interact with parental academic commitment, which in turn impacts student achievement. By comparing and contrasting these dynamics, the study sought to explore the extent to which alignment and misalignment between principals’ and teachers’ ratings on school leadership influence parental engagement in student learning and student success. Such comparisons are imperative, as persistent discrepancies between principals and teachers on school leadership will significantly impact student achievement. Moreover, understanding how different perceptions of school leadership could shape parental engagement in student academics would shed light on fostering more effective school-home collaborations, thus enhancing overall school effectiveness. This study seeks to raise awareness of searching for a cohesive vision of educational leadership among different stakeholders, promote collaborations, bridge the gaps, and find unity to improve student outcomes.

In addition to the comparative nature of this study between how different principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of school leadership are, and how the divergences can impact student learning, we are also interested in seeing if geographical location (Hong Kong and Macao) and the differences in the educational system would impact how effective school leadership was delivered to students. Educational leadership policies in Hong Kong and Macao have both undergone substantial changes, and each of them has a unique social-political context (

Education Bureau, 2021;

Morris & Vickers, 2015;

Yang, 2024).

1.4. Principal and Teacher Perceptions of Leadership

Principals and teachers often exhibit noticeably different views on the effectiveness of principals’ leadership roles and responsibilities. Principals are more focused on how educational policies are strategically planned, such as the development and implementation of educational policies, organizational administration, and school-wide planning (

Leithwood et al., 2020a;

Spillane & Diamond, 2007). School leaders who intentionally use participatory leadership practices, use effective decision-making processes to improve organizational effectiveness and align different stakeholders’ expectations in their daily operations (

Kaya et al., 2025). On the contrary, teachers may emphasize more direct practices, classroom management, instructional practices, and their relationships with students and parents, which they perceive to be more directly impactful on teaching quality (

Collie et al., 2012). If principals and teachers are not on the same page, that can further create disconnections between the school administrative team and teachers, which can adversely impact the collaborations and the overall school climate (

Price, 2012). Their disconnections in priorities in daily schoolwork can sometimes contribute to misalignment between principals and teachers pertaining to shared goals, values, and expectations.

1.5. Leadership in Hong Kong

The educational landscape in Hong Kong has been shaped by many factors, such as its unique political role, as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) from China mainland since 1997. The educational reforms not only impact school effectiveness but also student outcomes. One notable change in Hong Kong was the introduction of School-Based Management (SBM) during the early 1990s, aiming to decentralize the decision-making authority and return the autonomy and accountability to school leaders (

Szeto et al., 2015). That being said, this transition caused a big change in terms of the roles of school leaders, making collaborative and instructional leadership the focus of leadership practices (

Szeto, 2020).

Hallinger and Ko (

2015) investigated how principal leadership impacted school capacity and student learning in the Hong Kong context, and the study discovered the significance of strategic leadership in the process of establishing school improvement, especially with the high level of accountability in Hong Kong’s education system.

To et al. (

2023) explored the relationship between principal leadership, professional learning communities (PLC), and teacher commitment in Hong Kong. Findings suggested that effective leadership positively influenced teacher commitment by mediating professional learning communities.

1.6. Leadership in Macao

In contrast, existing literature on educational leadership in the Macao context is relatively scarce. However, current literature indicates that the educational leadership practices in Macao are largely impacted by the unique social-cultural context and influences from the Portuguese administration (

Szeto et al., 2015). Similarly, Macao’s education system was traditionally centralized, with the government playing a pivotal role in policy formulation and implementation. In recent years, Macao has been focusing on improving principal professional development. Legislations have been introduced to promote teacher collaboration, curriculum development, and technology integration in student teaching and learning. However, challenges and pushbacks remain in fostering a culture of shared leadership, and resources were limited in realizing the changes (

Yang, 2024). Furthermore, Macao has placed a strong emphasis on diversifying its economy beyond the gambling industry and reflected the emphasis on educational policies by encouraging and supporting the development of new industries (

Associated Press, 2024).

Both Hong Kong and Macao serve as Special Administrative Regions (SARs) and have undergone profound educational reforms in response to aligning more closely with China’s national objectives. However, their responses to policy changes were largely bound to their social-political contexts. Comparing and contrasting not only how principals and teachers differ, but also how geographical locations can contribute to how the role of school leadership functions to impact parental commitment and student outcomes.

1.7. Impact of Parental Involvement on Student Outcomes

Parental engagement has long been consistently confirmed to be a significant contributor to positive student outcomes (e.g.,

Erdem & Kaya, 2020;

Castro et al., 2015;

Özyıldırım, 2024). Expanding upon his previous research (

Hattie, 2009),

Hattie (

2023) synthesized more than 2100 meta-analyses that encompassed more than 130,000 studies involving over 400 million students internationally. This comprehensive masterpiece examined the impact of various school-related factors on student achievement. The updated analysis revealed that parental involvement—indicated by high expectations of student success, supportive learning environments, and consistent communications with schools—yielded an effect size of 0.50, suggesting a moderate positive impact on student learning.

Castro et al. (

2015) conducted a meta-analysis with 37 empirical studies published between 2000 and 2013, and their research confirmed that parental involvement and student academic performance demonstrated a positive relationship. Furthermore,

Özyıldırım (

2024) also conducted a meta-analysis exploring how parent involvement may influence student academic motivation. The study highlighted a small, yet statistically significant impact of parental involvement on student outcomes. School leadership often exerts a direct impact on school-related variables, such as parental involvement. In schools where principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of leadership effectiveness are aligned, they are more likely to create an enabling environment for both parents and students, encouraging parents to participate in school activities, which could, in turn, help improve student academic outcomes (

Alhosani et al., 2017;

American Psychological Association, 2019;

Hornby & Lafaele, 2011;

National Parent Teacher Association, 2022).

Gordon and Seashore Louis (

2009) suggested that when school leaders actively seek to establish positive relationships with parents and neighboring communities, they have better overall student outcomes. However, the process of partnering with parents to help improve student outcomes cannot be achieved without the help of teachers. Teachers often serve as the direct point of contact for parents; thus, their attitudes regarding school leadership determine how parents perceive the schools. Despite the fact that the benefits of parental involvement on student achievement were well-documented, numerous barriers—such as time constraints, insufficient communication from schools, and socioeconomic challenges—oftentimes impede meaningful parental engagement, especially among marginalized communities (

Calderon-Villarreal et al., 2025).

Dor and Rucker-Naidu (

2012) demonstrated that teachers’ perceptions of parental engagement and their feelings toward it significantly impacted teacher-parent actions and the overarching school culture. Furthermore,

Sharabi and Cohen-Ynon (

2022) found that teachers play an imperative role in the parent-school relationship, helping with clear communication and boundary setting. Inconsistencies in leadership perceptions between principals and teachers can result in ineffective communication with parents, which further discourages parental engagement around schools.

In addition, highly aligned principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of leadership practices not only facilitate parental involvement in terms of improving student outcomes but also engage parents in ways that extend beyond participating in school events that are directly related to student achievement. More specifically, parents may feel more motivated to take part in the school decision-making process, volunteer in school activities, and have higher academic expectations of students. For instance,

Hoover-Dempsey et al. (

2005) maintained that school leadership has an indirect positive impact on student achievement by mediating parental involvement, making the alignment of leadership perceptions between school leaders and teachers important.

1.8. Influence on Parental Expectations

Similarly, parental expectations of students’ academic achievement are also heavily influenced by school leadership, especially in how school principals communicate academic goals and establish high organizational standards (

Al-Mahdy et al., 2018). When the leadership insights are unified between principals and teachers through shared leadership, they can communicate to the parents about the school’s educational values and goals more effectively. For instance,

Smith et al. (

2021) highlighted that when school leaders care about family engagement and provide professional development opportunities for teachers in this area, we often see a significant enhancement in teachers’ family engagement strategies.

Gibson (

2024) proposed a shared leadership model at the elementary level, which led to enriched teaching instructions and improved community engagement. Misalignment in leadership perceptions, on the other hand, can potentially create misunderstandings, conflicting messages, and ineffective distractions, making the schools as a whole even harder to help students improve academic outcomes.

Hoover-Dempsey et al. (

2005) indicated that parents set higher academic expectations for their children when school leaders are collaborative, and the school environment is enabling. When school leaders and teachers collaborate effectively, they collectively create a trusting and encouraging environment for parents. Furthermore, parents within an enabling and collaborative school are more likely to feel their involvement in the student’s learning process is valued.

Sadiku and Sylaj (

2019) argued that students’ academic performance was enhanced through optimized family-school collaboration. In addition, the

U.S. Department of Education (

2025) emphasized the importance of strong family-school partnerships in helping improve student learning and increase student graduation rates.

1.9. Effect on Student Achievement

The ultimate goal to improve the consistency in perceptions of school leadership between principals and teachers, and to encourage meaningful parental involvement, is to enhance student achievement (

Gordon & Seashore Louis, 2009;

Smith et al., 2021). When leadership perceptions are consistent, the schools are benefited in various ways, such alignment smoothly delivers enhanced instructional practices, better learning resources, and wider community engagement, all of which are directed to the common goal: to improve student achievement.

Sebastian et al. (

2016) explored the relationships among principal leadership, teacher leadership, and classroom instruction, and found teacher leadership to be a significant mediator between school leadership and classroom instruction. Their study highlighted the important role of teacher-leader collaboration and cohesion. In schools where principals and teachers share consistent views on leadership priorities, the instructional practices are more likely to be aligned with the overarching school goals, making it more effective in promoting students’ positive learning outcomes. Research from

Leithwood et al. (

2020b) highlighted how shared leadership practices and visions could foster a collaborative environment, facilitating coherence in teachers’ instructional practices and student performance.

In contrast, when leadership perceptions diverge between principals and teachers, it can lead to fragmented efforts and conflicted actions, which can, in turn, further minimize instructional effectiveness.

Louis et al. (

2010) emphasized the importance of strong and widely accepted school leadership and indicated that its impact on student learning is second only to classroom instruction, further underscoring the importance of aligned leadership perceptions.

Doss and Tosh (

2019) highlighted the discrepancies between principals and teachers in how they perceive instructional leadership.

1.10. The Role of Socioeconomic Status (SES)

School-level socioeconomic status (SES) is often included when investigating how school leadership and other related school factors influence student learning (

Erdem & Kaya, 2020;

Leithwood et al., 2020b;

OECD, 2022). School-level SES serves as a significant contributor to the dynamics between principal leadership, parental involvement, parental expectations, and student achievement in K-12 settings. While SES can act both as a mediator and as a moderator, this study exclusively focuses on its moderating role in the proposed theoretical models. As a moderator, SES impacts not only the direction, but also the strength of the relationships amongst school leadership, parental involvement, and student achievement (e.g.,

Leithwood et al., 2020b). Schools with better SES are oftentimes equipped with greater education resources and more time from leaders and teachers allocated to help students improve their academic performance; thus, parental involvement has a larger positive impact on student achievement. On the flip side, schools that suffer from financial constraints are frequently facing other challenges, making the educational stakeholders (e.g., teachers and parents) harder to stay laser-focused on helping students thrive in academia (

Erdem & Kaya, 2020;

Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2005). Under such circumstances, the impact of parental involvement can be much weaker, statistically insignificant, or even negative on student outcomes.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions/Hypotheses

In this study, we indirectly compared how the different perceptions of school leadership between principals and teachers impact the influence of leadership practices on student outcomes through mediating parental involvement. More specifically, we ran two separate SEM models with school leadership measured by EDULEAD (principal-perceived school leadership) and LEADSHIP (teacher-perceived school leadership).

The research questions related to the principal-perceived school leadership SEM model (Model 1) are listed as follows:

How does school-level SES (ESCS) influence educational leadership (EDULEAD), parental involvement (PARINVOL), and parental expectations (PAREXPT)?

What is the relationship between parental involvement (PARINVOL) and parental expectations (PAREXPT)?

How do educational leadership (EDULEAD) and SES (ESCS) impact parental involvement and expectations?

What are the direct effects of educational leadership (EDULEAD) on student achievement in science, math, and reading?

To what extent do parental involvement (PARINVOL) and parental expectations (PAREXPT) mediate the relationship between educational leadership (EDULEAD) and student achievement (science, math, and reading)?

Does school-level SES (ESCS) moderate the relationships between educational leadership, parental involvement, parental expectations, and student achievement?

The research questions related to the teacher-perceived school leadership SEM model (Model 2) are listed as follows:

How does school-level SES (ESCS) influence school leadership (LEADSHIP), parental involvement (PARINVOL), and parental expectations (PAREXPT)?

What is the direct effect of school leadership (LEADSHIP) on parental involvement (PARINVOL) and parental expectations (PAREXPT)?

How does school leadership (LEADSHIP) indirectly influence student achievement (science, math, and reading) through parental involvement and expectations?

To what extent do parental involvement (PARINVOL) and parental expectations (PAREXPT) mediate the relationship between school leadership (LEADSHIP) and student achievement (science, math, and reading)?

How do parental involvement and expectations independently influence student achievement in science, math, and reading?

Does SES (ESCS) mediate the relationship between leadership (LEADSHIP) and parental factors (PARINVOL and PAREXPT)?

Does SES (ESCS) moderate the relationships between leadership (LEADSHIP), parental factors, and student achievement?

2.2. Sample and Data Sources

Data to answer the research questions were directly derived from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2022 data cycle. We only used data from Hong Kong (HKG) and Macao (MAC) for this study as the researchers wanted to focus on exploring the questions in a Chinese setting. More specifically, both HKG and MAC are the special administrative regions (SARs) of China, having some similarities and differences in their historical developments and education systems. In PISA 2022, data were organized by participant roles; original raw datasets (school questionnaire, teacher questionnaire, and student questionnaire with parent data) were available. With all data from Hong Kong and Macau, we used responses from 202 schools (156 Hong Kong Schools and 46 Macao schools), 4251 teachers (2335 from Hong Kong and 1916 from Macao), 10,291 parents (for each student participating in PISA 2022, one parent would also fill out a parent questionnaire), and 10,291 students (5907 from Hong Kong and 4384 from Macao). In addition, socioeconomic status data were available at the student level; for analysis purposes, SES was aggregated at the school level.

3. Measures

A weighted likelihood estimation (WLE) variable is imputed utilizing advanced statistical techniques to provide unbiased and accurate estimates of individuals’ skills or attributes (

Adams & Wu, 2002;

OECD, 2022,

2023;

Rasch, 1960;

von Davier et al., 2009b;

Wu et al., 2007). PISA uses sophisticated survey designs with stratified sampling, making it require weighting to reinforce that estimates are representative of the population (

OECD, 2023). WLE variables use the Item Response Theory (IRT) as their theoretical background. WLE variables measure latent constructs (variables that cannot be directly measured), and the advantage over raw scores is that they account for different levels of difficulty of test items and the probabilistic nature of responses, enhancing the precision and fairness of cross-sectional designs across different test-takers (

OECD, 2022). In this study, if a variable was available in WLE format, the researchers directly utilized the WLE variables for data analyses.

3.1. School Leadership (SL)

We utilized two sources to assess school leadership (principal-rated school leadership vs. teacher-rated school leadership). First of all, principal-rated school leadership was derived from a (WLE) variable EDULEAD, from the School Questionnaire. WLE variables in PISA represent proficiency estimates of latent traits derived from participant responses to the relevant items or survey questions. EDULEAD (WLE) was calculated from seven items (SC201Q01JA, SC201Q03JA, SC201Q04JA, SC201Q05JA, SC201Q06JA, SC201Q07JA, and SC201Q11JA) in the EDULEAD scale. Principals were asked about the frequency they engage in certain leadership practices, such as “taking actions to support co-operation among teachers to develop NEW teaching practices”. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Never or almost never to 5 = Every day or almost every day. The final EDULEAD (WLE) was a continuous variable at the school level.

Second, teacher-rated school leadership (LEADSHIP) is also a WLE variable, derived from the LEADSHIP scale in the Teacher Questionnaire in PISA 2022. The LEADSHIP scale is also comprised of seven 4-point Likert scale items (TC253Q01JA, TC253Q02JA, TC253Q03JA, TC253Q04JA, TC253Q05JA, TC253Q06JA, and TC253Q07JA). Teachers were asked to rate how often their principals engaged in certain leadership practices. Sample item, such as “my principal took actions to support co-operation among teachers to develop NEW teaching practices”. It is worth noting that the principal-rated and teacher-rated leadership items were almost identical in terms of leadership practices/activities. However, the answer categories for LEADSHIP items were from 1 = Never or rarely to 4 = Very often.

3.2. School-Level SES (ESCS)

PISA uses the economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS) index as a composite measure at the student level to quantify a student’s socioeconomic background, which consists of three key components, namely, parental education, parental occupation, and home possessions (

OECD, 2022). The ESCS index indicates the level of resources available to students at home, and such an index is critical in understanding equity and student performance in different educational systems. It is standardized across all participating countries, thus suitable for international comparison. Typically, ESCS has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 across all OECD countries and regions. For our study, ESCS was aggregated at the school level.

Student-level SES was measured by the Economic, Social, and Cultural Status Index (ESCS) in PISA 2022. This composite index was developed by the OECD to reflect students’ socioeconomic backgrounds based on parental education level, parental occupation, and home possessions (

OECD, 2022). For analysis convenience, this index was aggregated to the school level. This variable was used as a moderator in the SEM models to examine how the school-level SES would impact school leadership, PAC, and student achievement.

3.3. Parental Involvement (PARINVOL)

Parental Involvement is also a student-level WLE variable. The overarching question was “[d]uring <the last academic year>, have you participated in any of the following school-related activities?” PARINVOL items were rated on a Y/N basis. This subscale has 10 items, covering school-related activities, such as student behavior, academic progress, volunteering, and after-school learning support for students. Sample items of this subscale include “[l]ast year, have you participated in local school government, e.g., parent council or school management committee”.

3.4. Parent Expectations on Students (PAREXPT)

In PISA 2022, parent expectation is also a WLE variable derived from the PAREXPT scale in the Student Questionnaire (parents’ responses to certain parental aspects were included in the student questionnaire). This variable measures parental expectations on their children’s academic performance, how far they expect the students to progress, and how successful they will be in academia and future professional life. This WLE variable also captures how parental aspirations and expectations might influence student motivation, achievement, and outcomes. More specifically, this is an index value from 1 to 8 depending on parents’ responses to items from PA183Q01JA—PA183Q08JA. The higher the “yes” frequency, the higher the index value, suggesting a more positive and higher parental expectation of their children.

3.5. Student Achievement (SA)

PISA 2022 provides reading, math, and science as key measures of student achievement; these subject matters provide fundamental information and knowledge about students’ academic ability levels (

OECD, 2022,

2023). In particular, each of the three domains is provided in the format of plausible values (PVs), accounting for the uncertainty in measuring a student’s true ability. It is worth noting that these values are not the observed test scores for individual students but rather are random draws from a student’s performance distribution, representing a student’s ability based on their test performance on partial test questions and also their background information.

In particular, plausible values can be used to assess student-level academic proficiency in a way that measurement error and sampling variability can be accounted for, especially in international large-scale datasets (

OECD, 2022;

von Davier et al., 2009a;

Wu et al., 2007). In PISA 2022, each domain has ten plausible values (e.g., PV1MATH to PV10MATH), and these plausible values were randomly drawn from each student’s ability distribution. Plausible values come from item response theory (IRT) models, and background questionnaire responses (e.g., student SES, school environment) can be incorporated into PVs to refine ability estimates. That being said, this student achievement approach makes it possible to assess student academic performance with contextualized factors.

More importantly, plausible values should not be used directly for data analyses, and if multiple values are available, they should not be simply averaged and be used as the final value for a subject matter (

OECD, 2022;

Wu et al., 2007). Instead, for each subject matter, a comprehensive multiple imputation process was applied, and Rubin’s rules (

Rubin, 1987,

1996) were used to calculate the pooled parameter estimates, within-imputation variance, between-imputation variance, total variance, and pooled standard error. Details are explained in the data analytics section.

3.6. Data Analysis Procedures

In this study, several data analytic techniques were involved to help answer the research questions. More specifically, for the two primary SEM models (one with principal-rated school leadership, the other with teacher-rated school leadership). First, descriptive statistics were provided for all included variables, which presented objective characteristics of the variables. Secondly, since the unit of analysis for both SEM models was the school. To justify aggregating EDULEAD, LEADSHIP, PARINVOL, PAREXPT, and the plausible values of student achievement (reading, math, and science) to the school level, a series of intra-class correlations (ICC) were calculated, utilizing SPSS 28 ANOVA random effects (

IBM Corp., 2021). The purpose of ICCs was to evaluate whether these variables demonstrated a significant clustering effect at the school level. ICC (1) and ICC (2) values were applied to assess whether the aggregations to the school level were statistically appropriate (

Bliese, 2000). More specifically, ICC (1) values were calculated to represent the variances that were attributed to the grouping effects, and ICC (2) values were calculated for the within-group agreement among participants.

Furthermore, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted at the school level to unveil the relationships among all variables. More specifically, for the ten plausible values of each subject matter (reading, math, and science), we initially aggregated each plausible value to the school level. As a result, each subject matter would have ten school-level aggregated plausible values. To account for the measurement uncertainty of plausible values (PVs) in our analysis, Rubin’s Rules (

Rubin, 1987,

1996;

Schafer & Graham, 2002;

von Davier et al., 2009a) were utilized to pool parameter estimates and variances across multiple imputations since plausible values were randomly drawn values from students’ posterior distribution of their latent abilities. Each plausible value combination (e.g., Reading PV1, Math PV1, and Science PV1) was treated as an independent dataset, and the same SEM model was run separately using LISREL 12 (

Scientific Software International, Inc., 2021), yielding a set of parameter estimates and standard errors. After obtaining statistical results for all ten plausible value combinations, R 4.4.1 studio (

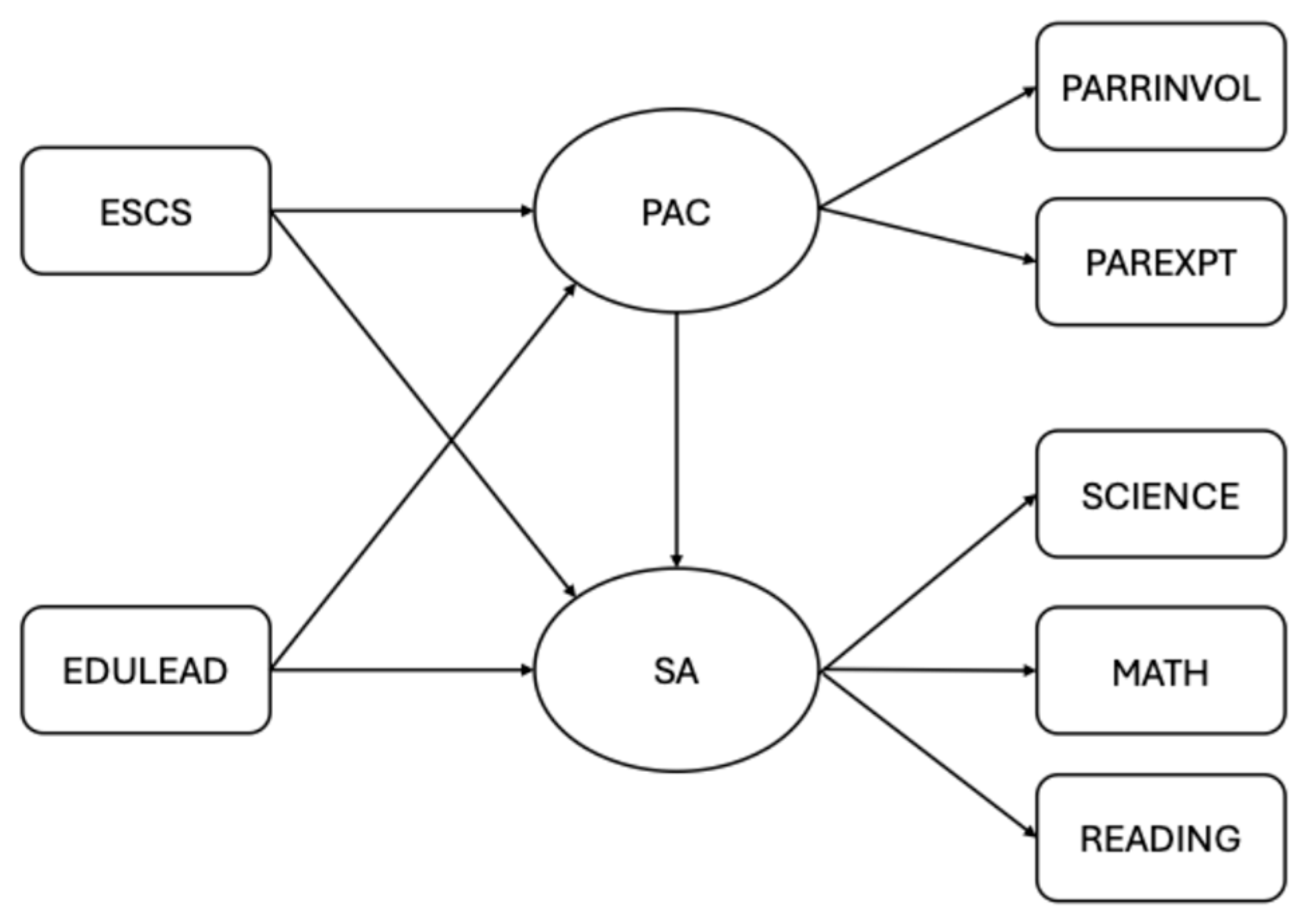

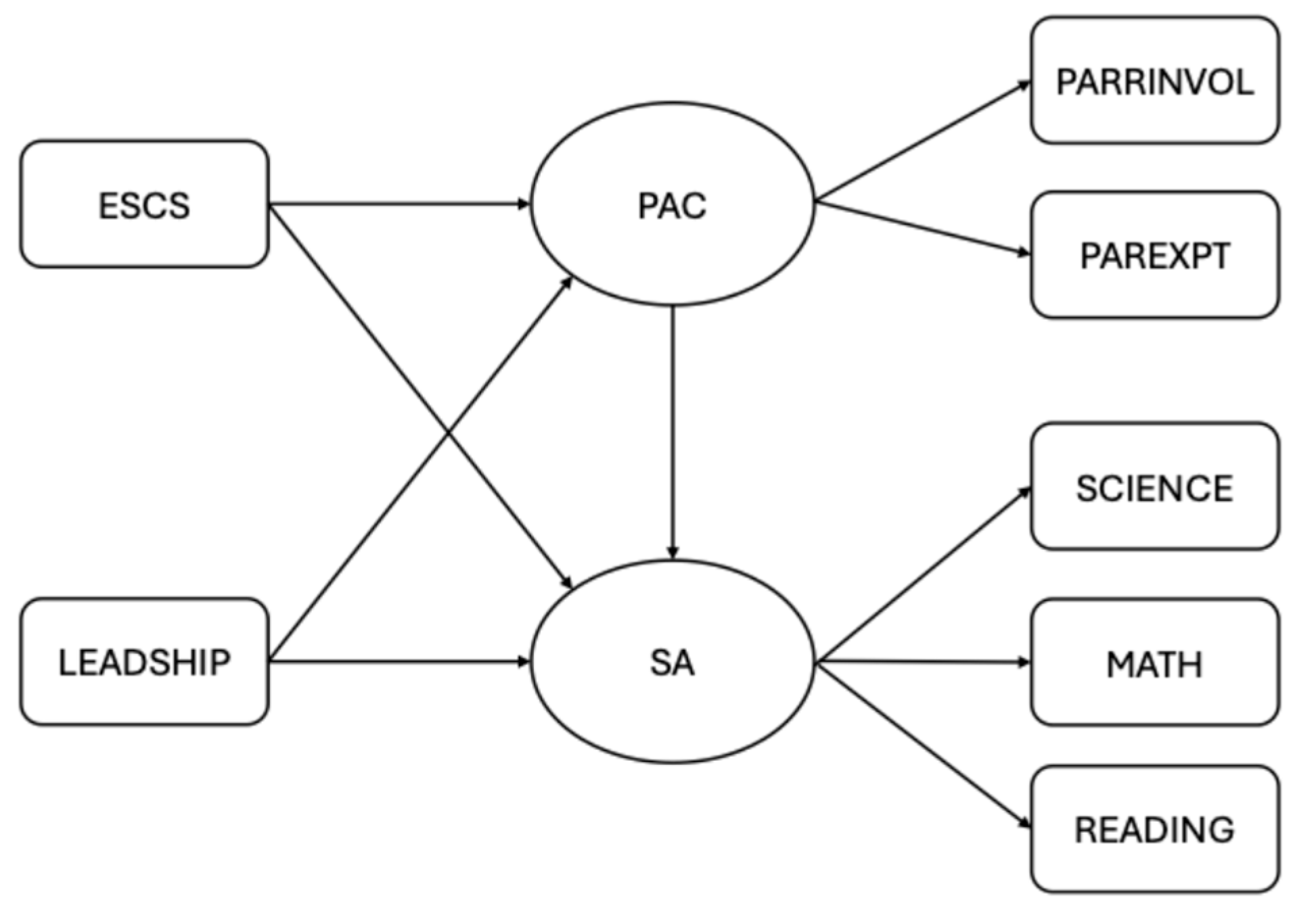

Posit Team, 2023) was utilized to apply Rubin’s Rules to combine these results, making sure the population-level interferences were able to reflect both within- and between-imputation variability; thus, we calculated the pooled parameter estimates, within-imputation variance, between-imputation variance, total variance, and pooled standard errors for the final (composite) results. Fit statistics were also pooled from the 10 separate plausible value analyses for both of the SEM models (principal- and teacher-rated school leadership). For the purpose of a better visual understanding, the theoretical SEM models are presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 below.

4. Results

The section presents statistical results, including a summary of descriptive statistics, a Pearson correlation matrix for all involved variables, a second-order CFA of the latent construct Parental Academic Commitment (PAC), item-level Rasch analysis (infit and outfit statistics), and finally, the two primary SEM models exploring how (principal-rated vs. teacher-rated) school leadership impacts student learning through mediating on PAC. The results were presented in the following subsections, organized by data analytic techniques.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

To reiterate, this study was primarily interested in comparing differences in leadership practices in two special administrative regions (SARs), namely, Hong Kong and Macao in China, using the PISA 2022 dataset. After subsetting participants from Hong Kong and Macau and conducting data cleaning, we obtained a final sample of 202 schools (156 in Hong Kong, 46 in Macau), 4251 teachers (2335 in Hong Kong, 1916 in Macao), 10,291 students (5907 in Hong Kong, 4384 in Macau), and 10,291 parents (5907 in Hong Kong, 4384 in Macau). Among the 202 schools, 49 (31.8%) were public, 4 (2.6%) schools were private independent, and 101 (65.6%) were private government-independent. Forty-eight schools did not provide valid school-type information. When it comes to the teachers, 2066 (48.6%) were male, and 2185 were female (51.4%); 3333 (78.4%) teachers were born in the country/region of the test, while 918 (21.6%) were born in other countries/regions. In terms of teachers’ age, 769 teachers were between 20 and 29 years old (18.1%) at the time of data collection, and 1318 (31.0%) were between 30 and 39 years old. Notably, 1208 (28.4%) teachers were between 40 and 49 years old, 878 teachers (20.7%) were between 50 and 59 years old, and only 78 (1.8%) teachers were 60 and above. When asked about whether or not they completed a teacher education or training program, 847 (20.3%) teachers indicated that they enrolled in a program with 1 year or less, 3142 (75.2%) teachers completed a relevant program that lasted more than 1 year, and 191 teachers (4.6%) indicated that they did not complete a training program.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that each student had one parent/guardian answer parent-related questions, resulting in the same sample sizes for both parents and students. HISCED (parent’s highest level of education). Most of the students from our sample were 15 to 16 years old; 4972 (48.3%) were female, and 5319 (51.8%) were male. Last but not least, as for parents, 5762 (58.1%) earned a high school diploma or less, 695 (7.0%) completed short-cycle tertiary education (e.g., associate degrees), 1322 parents (13.3%) completed a bachelor’s degree, 877 parents (8.8%) earned master’s degrees, and finally 432 (4.4%) earned a doctorate.

4.2. Intra-Class Correlation

Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) statistics are commonly used to evaluate the consistency of a variable or a measurement to see the percentage of variance accounted for by the hierarchical nature of the dataset or multilevel models (

LeBreton & Senter, 2008). More specifically, ICC (1) calculates the proportion of the variance in an aggregated variable that can be attributed to the grouping effect. It indicates the extent to which individual participants’ scores are similar or consistent within the same group. In addition, ICC (2) measures the consistency of aggregated group means, and this statistic indicates the extent to which the group mean represents individuals in the specific group. ICC (2) can be utilized to justify data aggregation, which in our case, is to aggregate student achievement, parental involvement, student SES, and parental expectations at the school level.

For a hierarchical variable to be reliable, the ICC (1) value should be greater than 0.05 and statistically significant. Higher ICC (1) values (>0.10) demonstrate the greater within-group effect and significant group-level similarity. As for ICC (2), values over 0.70 are considered acceptable, and values greater than 0.85 are deemed excellent for group-level analysis (

Cohen et al., 2003). For all the variables that were required to be aggregated to the school level, detailed ICC (1), and ICC (2) values, in conjunction with significance levels, were included in

Table 1. To obtain the ICC statistics. We ran a random effect ANOVA for all aggregated variables. The

F test of significance for all the involved variables was statistically significant (

p < 0.001). For teacher-rated school leadership, parent-rated parental involvement, parent expectations on student achievement, and student-level SES, ICC (1) values were between 0.07 and 0.29; the values for ICC (2) ranged from 0.73 to 0.94, confirming the justification of school-level aggregation. Furthermore, for all 30 plausible values from reading, math, and science, the ICC (1) and ICC (2) values were very similar (ICC (1) ranging from 0.30 to 0.36, and ICC (2) ranging from 0.95 to 0.96). All the ICC statistics strongly justified the school-level aggregation.

4.3. Correlation Matrix

For the convenience of displaying relationships among all the observed variables. A Pearson correlation matrix was provided (see

Table 2). To better demonstrate the correlations at the school level, all the relevant variables were aggregated before the correlation analysis. More specifically, for reading, math, and science, 10 plausible values were used to obtain a multiple-imputed composite score for each subject matter using R Studio (

Posit Team, 2023), and then aggregated to the school level. However, it is worth noting that for the SEM analysis, we analyzed the same 2 SEM models (principal- and teacher-rated school leadership) using 10 sets of student achievement (e.g., Reading PV1, Math PV1, and Science PV1) and then calculated the pooled statistics.

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for all involved variables at the school level (n = 202). The standard deviations for all the non-achievement variables were relatively small. For student achievement, the standard deviations were larger but relatively consistent.

Table 3 and

Table 4 are correlation matrices (principal- vs. teacher-rated school leadership) showing the relationships among observed variables at the school level. As indicated in

Table 3 and

Table 4, school-level student SES was positively correlated with parental involvement (

r = 0.20), parent expectations of student success (

r = 0.52), science (

r = 0.61), math (

r = 0.61), and reading (

r = 0.57). Interestingly, for both principal-rated and teacher-rated school leadership, their correlations with other variables were not statistically significant. The rest of the correlations were all statistically significant, ranging from moderate to strong.

4.4. Structural Equation Models (Rubin’s Rule)

To reiterate, we ran two identical SEM models, except that for school leadership, model 1 used principal-rated school leadership (EDULEAD), and model 2 utilized teacher-rated school leadership (LEADSHIP). Our intention for this design was to indirectly compare how principals and teachers might perceive school leadership differently and how such school leadership could function differently in our proposed SEM models. Both SEM models explored how school leadership impacted student achievement (measured by reading, math, and science) directly and indirectly through mediation on a latent construct of Parental Academic Commitment (PAC), measured by parental involvement (PARINVOL) and parents’ expectations of students’ academic success (PAREXPT). School-level SES functioned as a moderator in the theoretical models.

The theoretical model in

Figure 1 was tested using LISREL 12 and R. With each plausible value set, the same SEM models were performed in LISREL 12. All SEM standardized path coefficients and their standard errors, in conjunction with model fit statistics (e.g., RMSEA, SRMR, Chi-square, CFI, GFI, etc.), were then recorded on an Excel spreadsheet. For each SEM model, this process was repeated ten times. After the initial calculations were completed, R Studio (

Posit Team, 2023) was used to calculate the pooled parameter estimates, within-imputation variances, between-imputation variances, total variances, and pooled standard errors for each model. Detailed SEM pooled statistics were presented by each SEM model.

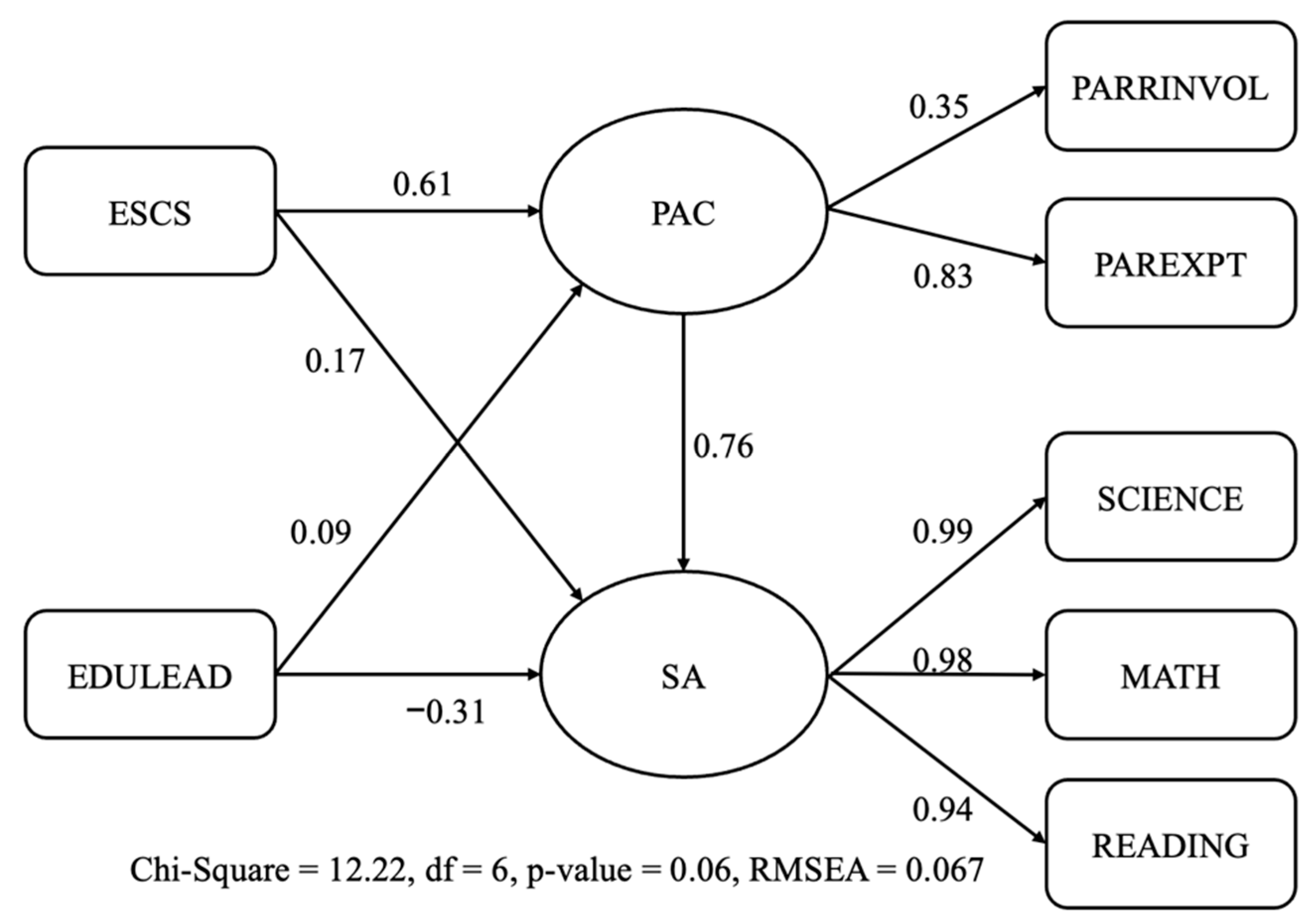

4.5. Model 1 Principal-Rated School Leadership

This SEM-MIMIC model explored how ESCS and EDULEAD (principal-perceived school leadership) influenced PAC and SA (see

Table 5). More specifically, it tested the mediating impact of PAC between EDULEAD and SA, while ESCS served as a moderator. ESCS was a strong positive predictor of PAC (β = 0.61), subsequently, PAC significantly predicted SA (β = 0.76) (See

Figure 3). ESCS indirectly impacted SA through PAC (β = 0.17). EDULEAD also demonstrated a positive but weak influence on PAC (β = 0.09). Interestingly, EDULEAD exerted a substantial negative impact on SA (β = −0.31). Moreover, both PAC and SA strongly and positively predicted their subordinate observed variables. In terms of the fit statistics, RMSEA = 0.067, SRMR = 0.015, χ

2 = 12.22,

df = 6,

p > 0.05. Last but not least, other fit indices, such as CFI, GFI, NFI, and NNFI had all well surpassed the 0.9, the acceptable level, indicating excellent fit.

4.6. Model 2 Teacher-Rated School Leadership

This SEM model explored the potential relationships among student SES, teacher-perceived school leadership, PAC (Parental Academic Contributions), and SA (Student Achievement). The results of this analysis suggested that ESCS significantly and strongly predicts PAC (β = 0.63;

p < 0.05), and has an insignificant and positive impact indirectly on SA through PAC (β = 0.18;

p > 0.05). (See

Figure 4 and

Table 6). Teacher-perceived school leadership had a weak and insignificant direct effect on PAC (β = −0.10;

p > 0.05), and subsequently, PAC had a substantial direct effect on SA (β = 0.69;

p < 0.05). LEADSHIP had a negligible and insignificant effect on SA (β = 0.01), implying a very limited direct influence on student achievement. Furthermore, PAC positively predicted PARINVOL and PAREXPT (β = 0.35 and 0.82, respectively), while SA also strongly predicted science, math, and reading (β = 0.99, 0.98, and 0.97, respectively). These strong path coefficients indicated robust connections between the latent constructs (PAC and SA) and their corresponding observed variables. This SEM model indicated an excellent fit with RMSEA = 0.035. SRMR = 0.017, χ

2 = 10.21,

df = 8,

p > 0.05. Additionally, fit statistics such as CFI (0.998), GFI (0.986), NFI (0.991), and NNFI (0.994) were all close to 1.0, suggesting excellent model-data fit (

Bedi & Bhale, 2023;

Bentler, 1990;

Bentler & Bonett, 1980;

Sörbom & Jöreskog, 1981;

Sathyanarayana & Mohanasundaram, 2024).

5. Discussions

The study provided empirical evidence on principals’ and teachers’ divergent understandings of school leadership and how that difference, in turn, impacted parental academic commitment and student outcomes. That being said, our discussion presents how principal-perceived and teacher-perceived school leadership differed in influencing parental academic commitment and student achievement, and how these findings filled in the literature blanks and advanced our awareness to explore more on this matter further. To improve clarity for different educational stakeholders, we highlighted that parental academic commitment (PAC) consistently predicted student achievement in both SEM models; its relationship to school leadership differed significantly depending on whether the school leadership was rated by principals themselves or their fellow teachers. The divergent patterns suggested that school improvement initiatives must be informed by both top-down (principal) and bottom-up (teacher) leadership perspectives.

Both MIMIC models explored school leadership’s direct and indirect impact on PAC and SA. Principal-rated school leadership (EDULEAD) positively predicted PAC but exhibited a moderately negative direct effect on student achievement. On the contrary, teacher-rated school leadership (LEADSHIP) negatively predicted PAC, and demonstrated a negligible direct impact on student achievement. Across both models, the impact of ESCS on PAC and SA remained consistent, suggesting the fundamental and pivotal role in parental engagement and student outcomes. The first model demonstrated a more nuanced leadership dynamic in conjunction with PAD and SA, where EDULEAD contributed positively to PAC but negatively to SA. In the second model, the effect was almost nonexistent. Both models indicated that PAC was a strong positive predictor of SA, further confirming the imperative role of parental support and engagement in student success. In addition, while school leadership functioned differently in each model, both models emphasized the pivotal role of SES and PAC in shaping student success.

5.1. Overall Strength of Leadership Effects

Regarding the impact and strength of school leadership in the SEM models, the principal-rated school leadership (EDULEAD) demonstrated a small yet positive impact on PAC (β = 0.09) and a moderate negative direct influence on student achievement (β = −0.31). On the contrary, the teacher-perceived school leadership (LEADSHIP) showcased a weak negative impact on PAC (β = −0.10), and a non-significant direct effect on student achievement. The differences in statistical results indicated that principals perceived themselves as being more influential in promoting meaningful parental engagement, whereas teachers did not view their principals as being highly impactful on school-parent dynamics or student academic outcomes. Teachers’ direct connection with day-to-day instructional responsibilities may explain the perception gap. These findings conformed with previous literature that principals and teachers perceive school leadership in divergent ways (

Day & Sammons, 2016;

Leithwood & Jantzi, 2000). Principals, when evaluating their own leadership practices, may emphasize more the strategic and administrative efforts that are aligned with policy implementation; teachers appeared to rate school leadership based on their daily experiences and their interactions with leaders. The empirical evidence in perception gaps further strengthened the necessity to be open-minded and creative in finding ways to promote cohesive policy implementation.

5.2. Mediation Through PAC and Impact on Student Achievement

PAC was proven to be a strong and significant mediator in both SEM models, predicting student achievement (β = 0.76 and β = 0.69, respectively). Furthermore, in Model 1, PAC demonstrated a significant yet weak mediation between principal-rated leadership and student achievement; however, in Model 2, the mediation of PAC from teacher-rated leadership to SA was even weaker and statistically insignificant. The differences implied that while PAC was a powerful contributor to student achievement, it was less impacted by teacher-perceived school leadership, possibly due to the fact that teachers tend to emphasize instructional autonomy rather than top-down directives.

It is worth noting that principal-perceived school leadership exhibited a significant negative direct effect on student achievement, while it was not the case in the teacher-perceived leadership model. The negative direct impact could suggest that principals’ leadership strategies may inadvertently misalign with teachers’ instructional practices and parental expectations at times, leading to an unfavored negative influence. The statistical results from both models collectively suggested that PAC helps transform the positive impact of school leadership into promoting student learning.

6. Conclusions

Using Hong Kong and Macao data from PISA 2022, this study examined how school leadership impacted parental academic commitment (PAC) and how PAC contributed to student achievement as measured by reading, math, and science. Particularly, principal-perceived and teacher-perceived school leadership were compared to investigate whether or not there existed significant discrepancies in principals’ and teachers’ understandings. The results demonstrated both similarities and distinctions in how principal-rated and teacher-rated school leadership impact PAC and student outcomes. Similarly, student socioeconomic status demonstrated a significant and positive impact on PAC, which in turn resulted in a significant and positive impact of PAC on student outcomes. In addition, for both SEM models, the impact of student SES on student outcomes and school leadership’s impact on PAC were all statistically insignificant. A notable difference between the 2 SEM models is that for principal-perceived school leadership, the direct impact of school leadership on student achievement was statistically significant, whereas the teacher-perceived school leadership illustrated an insignificant path to student achievement.

This study contributes to the current literature by emphasizing the awareness and importance of comparing different leadership perspectives between principals and teachers because teachers are the direct school policy prosecutors. If teachers have different understandings and views on how educational policies should be executed, the effectiveness of the policies is questionable. In addition, if the relationships between principals and teachers are passive, even with good policies, they are hardly beneficial to students. The ultimate goal in K-12 educational leadership is to mitigate the existing perception discrepancies and cultivate a mutual understanding of educational policies among different stakeholders. That said, when exercising leadership practices on a day-to-day basis, school leaders should be mindful of when conveying policies to teachers and acknowledge that teachers may have different perspectives and thoughts about these policies. Furthermore, school leaders should also understand where the differences lie and how big the discrepancies are, thus staying laser-focused on addressing the underlying issues. Future research is encouraged to focus on comparing principal-teacher differences in a more direct manner at international, domestic, and local levels.

Implications and Limitations

By using only HKG and MAC data from PISA 2022, there were several limitations of the study. First of all, while PISA 2022 data collection and data handling were, the selection of only two regions may not capture some nuances of school leadership perceptions due to its standardized survey design, and the exclusive focus on Hong Kong and Macao may pose some generalizability issues of the findings to other educational contexts with divergent socio-political dynamics. Practically, the findings in our study underscored the significance of nourishing leadership alignment between principals and teachers to provide effective support for meaningful parental involvement. When leadership perceptions are relatively unified among different stakeholders, expectations for families are oftentimes clearer and more consistent, which in turn strengthens the school-home relationship and promotes student learning growth. School leaders are encouraged to foster collaborative and enabling environments where teachers’ feedback can help shape leadership practices that are inclusive and grounded in daily instructional realities. As a result, future empirical studies should compare school leadership perceptions with more countries involved, in order to explore whether findings hold steady across different cultural and educational systems. Second, there were two sources (EDULEAD and LEADSHIP) measuring school leadership, and these sources were self-reported perceptions from principals and teachers, which may be subject to bias. Furthermore, even though Rubin’s rules were used while applying 10 sets of plausible values in the SEM-MIMIC models, it was still possible that this approach introduced a level of uncertainty, which could potentially affect statistical interpretations. Future research is encouraged to either use an international dataset with more plausible values or test the SEM models in different settings. While this cross-sectional design sheds some light on the relationships of school leadership, parental academic commitment, and student achievement, it is recommended that future research explore these dynamics over time to evaluate the changes and longitudinal trends. Last but not least, our findings highlighted the importance of school leadership on student achievement through the significant mediation of PAC on student achievement. Our findings also emphasized the importance of the leadership alignment between principals and teachers; future studies must explore professional development programs that can foster a shared understanding of leadership practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z.; software, S.Z.; validation, S.Z. and H.W.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, S.Z. and H.W.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.W.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study utilized data from PISA 2022, which did not require IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, R. J., & Wu, M. L. (2002). PISA 2000 technical report. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Alhosani, N. M., Kumar, V., & Christopher, A. (2017). School leadership and climate as determinants of student academic achievement. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(6), 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahdy, Y. F. H., Emam, M. M., & Hallinger, P. (2018). Assessing the contribution of principal instructional leadership and collective teacher efficacy to teacher commitment in Oman. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Parental involvement and student achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(9), 855–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associated Press. (2024, October 20). China’s Xi swears in new leader of casino hub Macao, telling the city to diversify economy. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/384759d1f46a32d122ba656bb9eaa3c4 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Bedi, H. S., & Bhale, U. A. (2023). SEM model fit indices: Meaning and acceptance of model fit literature support. Kindle Direct Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership & Management, 34(5), 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Villarreal, A., Garcia-Hernandez, A., Olvera-Gonzalez, R., & Elizondo-Garcia, J. (2025). Parental involvement barriers and their influence on student self-regulation in primary education. Education and Urban Society, 57(4), 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. K., Raudenbush, S. W., & Ball, D. L. (2003). Resources, instruction, and research. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(2), 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social-emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C., & Sammons, P. (2016). Successful school leadership. Education Development Trust. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED565740 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Dor, A., & Rucker-Naidu, T. B. (2012). Teachers’ attitudes toward parents’ involvement in school: Comparing teachers in the USA and Israel. Issues in Educational Research, 22(3), 246–262. [Google Scholar]

- Doss, C. J., & Tosh, K. (2019). Perceptions of school leadership: Implications for principal effectiveness. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2575z5-1.html (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Education Bureau. (2021). Policy initiatives of the education bureau. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/legco/policy-address/20211018_PA%20panel%20paper%20%28ENG%29final.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Erdem, C., & Kaya, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of the effect of parental involvement on students’ Academic achievement. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(3), 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W. (2024, May 27). Building community engagement and transforming school culture with shared leadership. EducationNC. Available online: https://www.ednc.org/perspective-building-community-engagement-transforming-school-culture-shared-leadership/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gordon, M. F., & Seashore Louis, K. (2009). Linking parent and community involvement with student achievement: Comparing principal and teacher perceptions of stakeholder influence. American Journal of Education, 116(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2011). Triangulating principal effectiveness: How perspectives of parents, teachers, and assistant principals identify the central importance of managerial skills. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1091–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2020). Effective instructional time use for school leaders: Longitudinal evidence from observations of principals. Educational Researcher, 42(8), 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Mitani, H. (2015). Principal time management skills: Explaining patterns in principals’ time use, job stress, and perceived effectiveness. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(6), 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. (2003). Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education, 33(3), 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1980–1995. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 9(2), 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. School Leadership & Management, 30(2), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Ko, J. (2015). Education accountability and principal leadership effects in Hong Kong primary schools. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(3), 30150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel: A synthesis of over 2100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 28.0. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, E., Atasoy, R., & Ozkul, R. (2025). Examination of decision-making processes of school administrators: Participation and effectiveness. International Journal of Studies in Education and Science, 6(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Day, C. (2007). Successful principal leadership in times of change: An international perspective. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020a). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2000). The effects of transformational leadership on organizational conditions and student engagement with school. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(2), 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2012). The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Sun, J. (2018). How school leaders contribute to student success: The four paths framework. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & Schumacker, R. (2020b). How school leadership influences student learning: A test of “The Four Paths Model”. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(4), 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonor, J. (2021). The role of leadership in shaping the future of education. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 27(S1), 5. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K. L., & Anderson, S. E. (2010). Investigating the links to improved student learning: Final report of research findings. The Wallace Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, P., & Vickers, E. (2015). Schooling, politics and the construction of identity in Hong Kong: The 2012 ‘Moral and National Education’ crisis in historical context. Comparative Education, 51(3), 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J. (2015). Creating communities of professionalism: Addressing cultural and structural barriers. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Parent Teacher Association. (2022). Building Successful Partnerships: A Guide for Developing Parent and Family Involvement Programs. In NEA today (Vol. 21, p. 48). Number 3. National Education Association of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2022). PISA 2022 technical report. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 assessment and analytical framework. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Özyıldırım, G. (2024). Does parental involvement affect student academic motivation? A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 43, 29235–29246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. (2023). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R (Version 2023.06.0) [Computer software]. Posit, PBC. Available online: https://posit.co/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Price, H. E. (2012). Principal–teacher interactions: How affective relationships shape principal and teacher attitudes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 48(1), 39–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Danish Institute for Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. B. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(434), 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, G. S., & Sylaj, V. (2019). Factors that influence the level of the academic performance of the students. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 10(3), 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayana, S. S., & Mohanasundaram, T. (2024). Fit indices in structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis: Reporting guidelines. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 24(7), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Software International, Inc. (2021). LISREL 12 for Windows [Computer software]. Scientific Software International. Available online: https://www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., & Huang, H. (2016). The role of teacher leadership in how principals influence classroom instruction and student learning. American Journal of Education, 123(1), 69–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, M., & Cohen-Ynon, G. (2022). Strategies used to gain effective parental involvement: School administration and teachers’ perceptions. International Journal of Education, 10(3), 1–14. Available online: https://airccse.com/ije/papers/10322ije01.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. E., Connors-Tadros, L., & Gebhard, B. (2021). Exploring the link between principal leadership and family engagement. Journal of School Psychology, 84, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörbom, D., & Jöreskog, K. G. (1981). The use of structural equation models in evaluation research. Department of Statistics, Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J. P., & Diamond, J. B. (Eds.). (2007). Distributed leadership in practice. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J., & Leithwood, K. (2015). Leadership effects on student learning mediated by teacher emotions. Societies, 49(1), 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, E. (2020). School leadership in the reforms of the Hong Kong education system: Insights into school-based development in policy borrowing and indigenising. School Leadership & Management, 40(4), 266–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, E., Lee, T. T. H., & Hallinger, P. (2015). A systematic review of research on educational leadership in Hong Kong, 1995–2014. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(4), 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Y. (2024). Influence of principal leadership across contexts on the science learning of students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 25, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K. H., Yin, H., Tam, W. W. Y., & Keung, C. P. C. (2023). Principal leadership practices, professional learning communities, and teacher commitment in Hong Kong kindergartens: A multilevel SEM analysis. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(4), 889–911. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, L. L. (2022). School organizational culture and leadership: Theoretical trends and new analytical proposals. Education Sciences, 12(4), 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2025). Parent and family engagement. Available online: https://www.kyspin.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Parent-and-Family-Engagement-Guidance-2025.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- von Davier, M., Gonzalez, E., & Mislevy, R. J. (2009a). What are plausible values and why are they useful? In M. von Davier, & D. Hastedt (Eds.), The role of international large-scale assessments: Perspectives from technology, economy, and educational research (pp. 9–36). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Davier, M., Sinharay, S., Oranje, A., & Beaton, A. (2009b). The statistical procedures used in TIMSS and PIRLS. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M., Adams, R., & Wilson, M. (2007). Multidimensional Rasch measurement using ConQuest. Applied Psychological Measurement, 31(3), 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R. (2024). Towards governmentality with Chinese characteristics: Higher education policymaking in post-colonial Hong Kong and Macao. Comparative Education, 60(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).