Teacher Well-Being—A Conceptual Systematic Review (2020–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Stage 1: Identifying Well-Being as a Tangled Term

- Stage 2: The identification of Heuristics

- Stage 3: The Classification of Heuristics

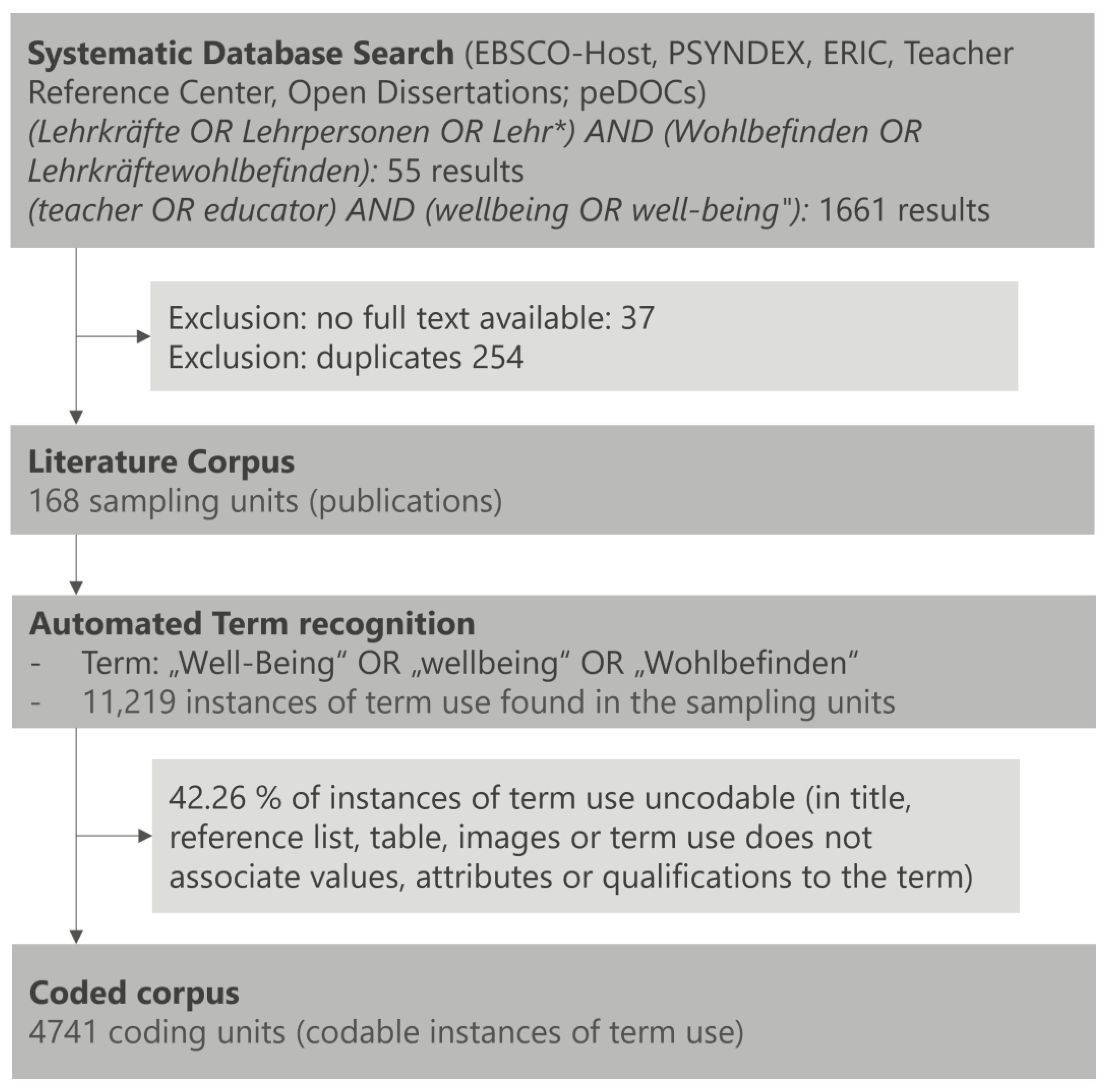

- Stage 4: Corpus Development

- Stage 5: Empirical Systematization of Classifications

3. Heuristics of Teacher Well-Being

4. Deductive Framework of Teacher Well-Being

5. Corpus Development

6. Results

6.1. Qualitative Results: Systematic Use of the Term TWB

6.1.1. The Perspective on Conditions

6.1.2. The Perspective on Components

6.1.3. The Perspective on Outcomes

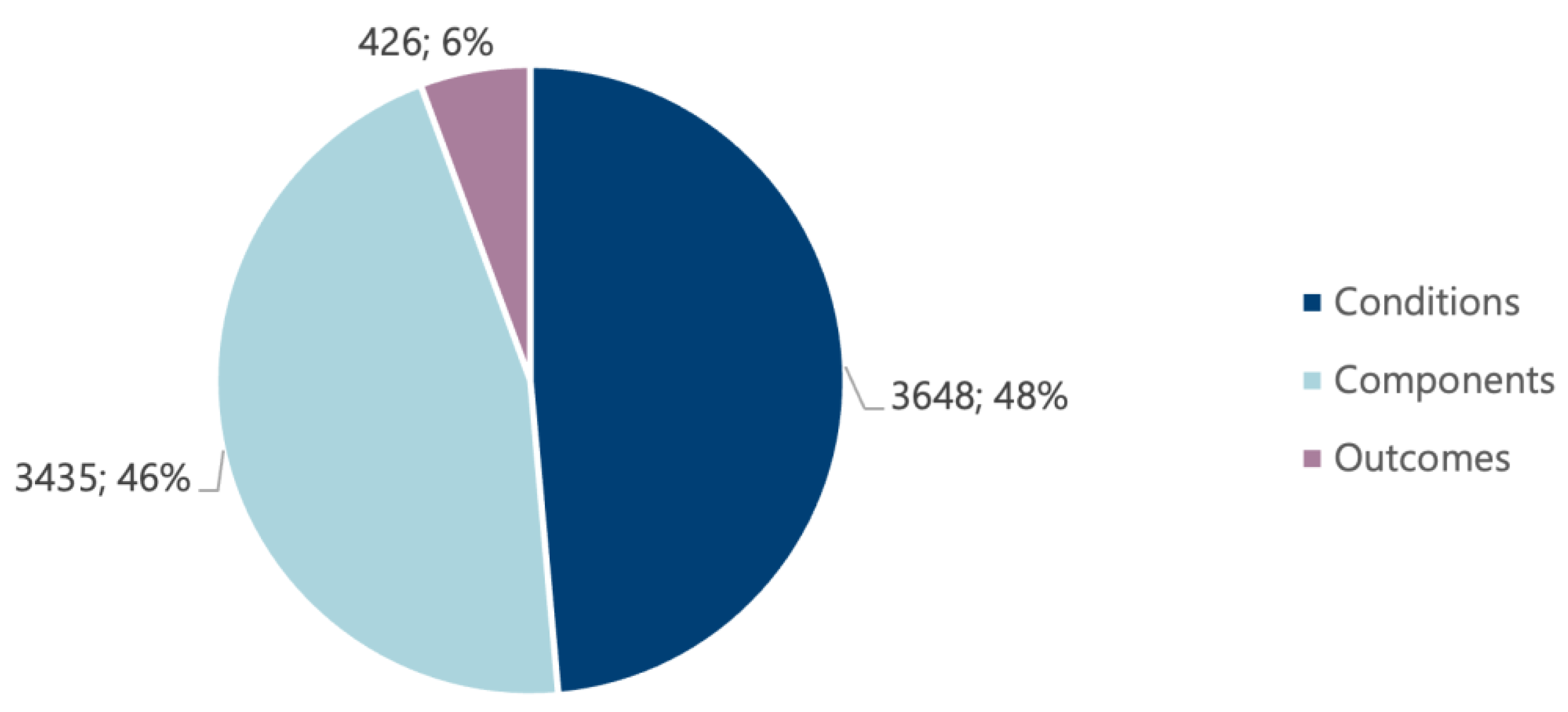

6.2. Quantitative Results: Frequency of Term Use (TWB)

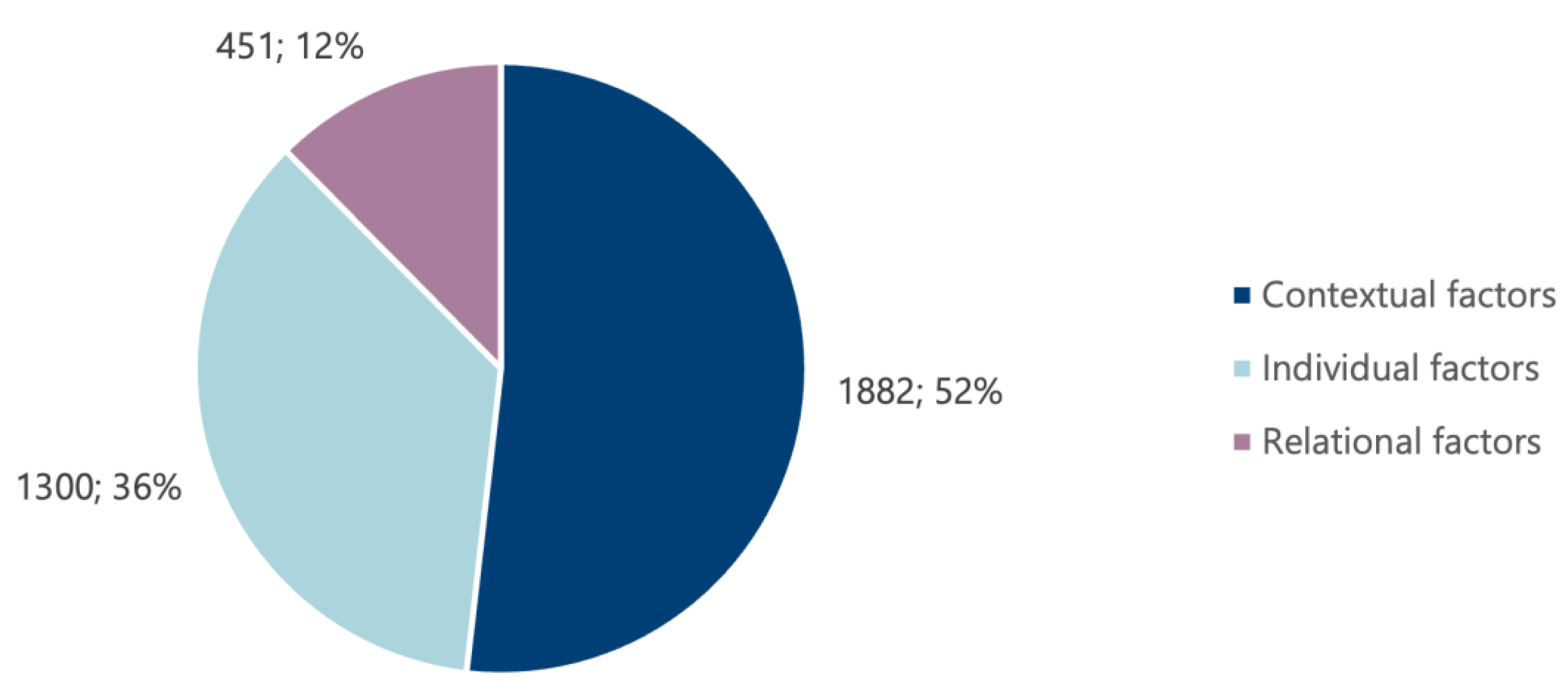

6.2.1. Prevalence of Terms Pertaining to Conditions

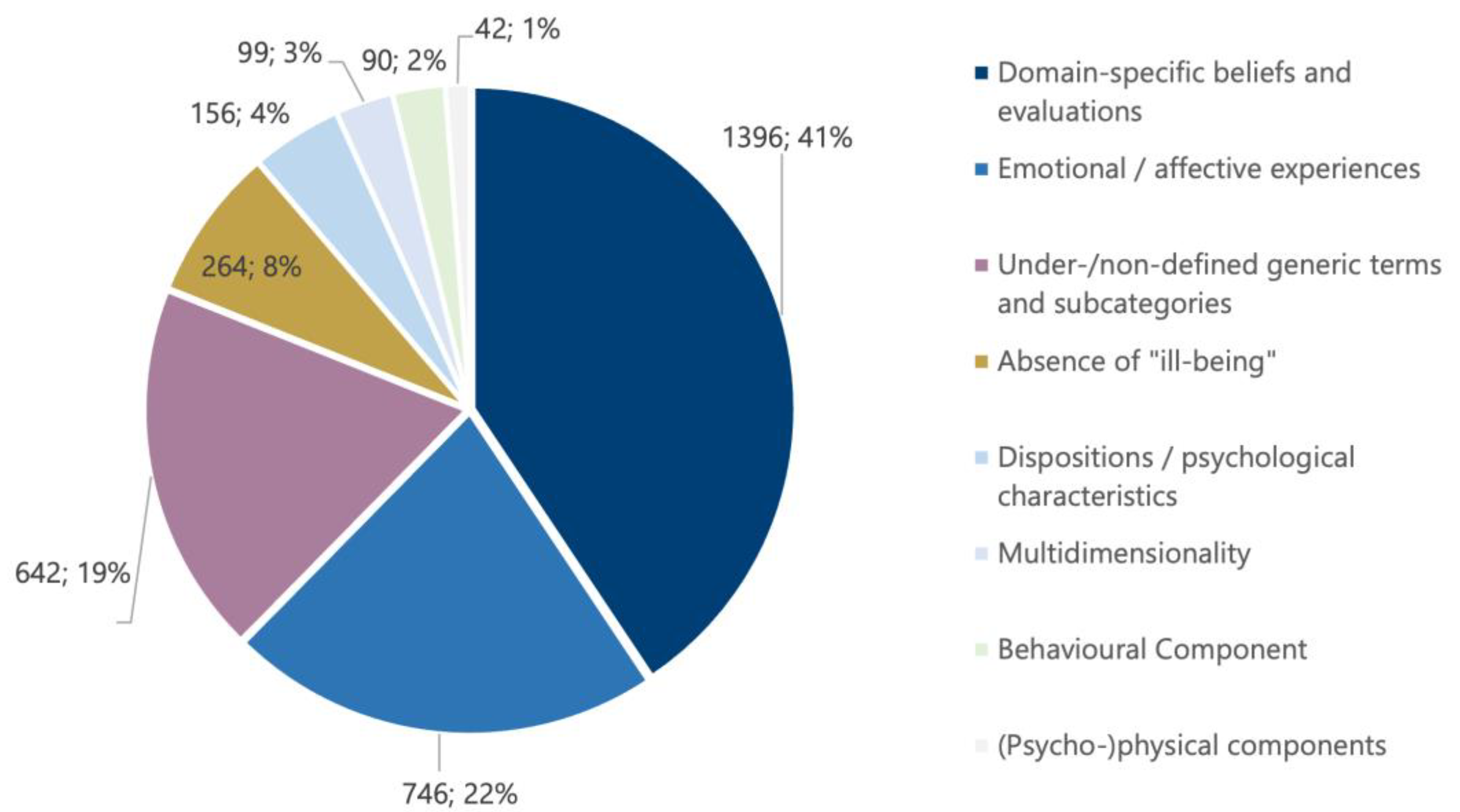

6.2.2. Prevalence of Terms Pertaining to Components

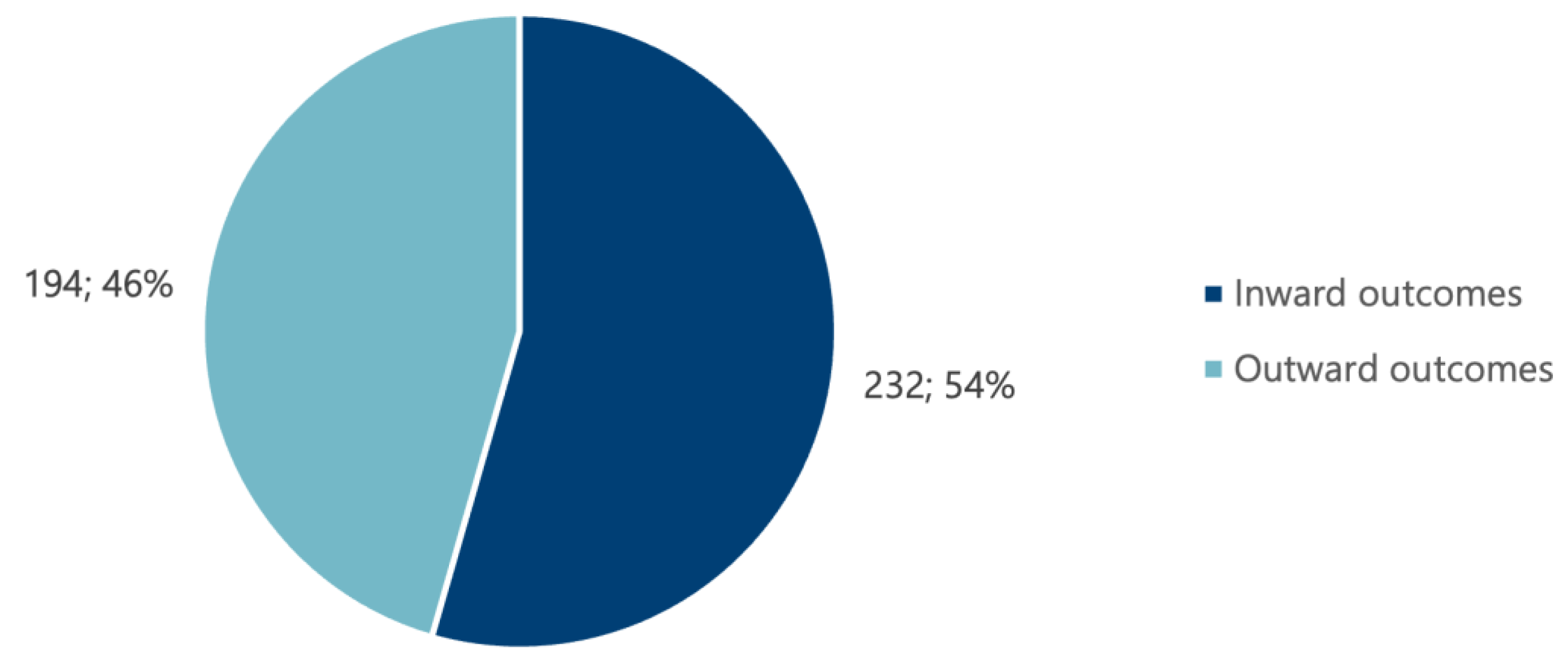

6.2.3. Prevalence of Terms Pertaining to Outcomes

7. General Synopsis

7.1. Central Insights into the Systematic Use of Terms

7.2. Central Insights into the Frequency of Term Use

8. Discussion

8.1. Fundamental Issues with “Framing” Differing Conceptualizations of Teacher Well-Being

8.2. Specific Challenges of Construct Allocation, Factors, and Definitions

8.3. Reflections on Quantifiable Focus Areas of TWB Concepts

8.4. Limitations

8.5. Research Outlook and Practical Implications

9. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PWB | Psychological well-being |

| REDS | Responses to educational disruption survey |

| SWB | Subjective well-being |

| TWB | Teacher well-being |

| 1 | A reference list of the final literature corpus can be found in the Supplementary Material. |

| 2 | The Supplementary Material includes the coding guidelines that were used to code the final literature corpus. |

| 3 | The Supplementary Material contains the detailed results regarding the systematic and frequency use of the term “TWB.” |

References

- Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., Köller, M. M., & Klusmann, U. (2020). Measuring teachers’ social-emotional competence: Development and validation of a situational judgment test. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrup, K., & Klusmann, U. (2021). Soziale Eingebundenheit mit Schülerinnen und Schülern: Welche rolle spielt sie für das berufliche wohlbefinden von Lehrkräften? [Social connectedness with students. What role does it play in teachers’ professional well-being?]. In G. Hagenauer, & D. Raufelder (Eds.), Soziale Eingebundenheit: Sozialbeziehungen im Fokus von Schule und LehrerIinnenbildung (pp. 271–286). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2018). APA dictionary of psychology. American Psychological Association. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Amirian, S. M., Amirian, S. K., & Kouhsari, M. (2023). The impact of emotional intelligence, increasing job demands behaviour and subjective well-being on teacher performance: Teacher-gender differences. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(1), 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, L., & Klassen, R. M. (2021). Teacher motivation and student outcomes: Searching for the signal. Educational Psychologist, 56, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenechea, I. (2022). Teachers’ perceived sense of well-being through the lens of mattering: Reclaiming the sense of community. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 7(4), 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, J. R., Spanos, S., Roberts, A., McGillivray, L., Li, S., Newby, J. M., O’Dea, B., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2023). Intervention programs targeting the mental health, professional burnout, and/or wellbeing of school teachers: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E., Reupert, A., Campbell, T. C. H., Morris, Z., Hammer, M., Diamond, Z., Hine, R., Patrick, P., & Fathers, C. (2022). A systematic review of evidence-based wellbeing initiatives for schoolteachers and early childhood educators. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2919–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilz, L., Fischer, S. M., Hoppe-Herfurth, A.-C., & John, N. (2022). A consequential partnership: The association between teachers’ well-being and students’ well-being and the role of teacher support as a mediator. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 230(3), 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumhardt, D. (2020). Perceptions of the elementary principal role in teacher well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Creighton University]. RIS. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, C. O., & Lopes Cardozo, M. (2023). Researching teacher well-being in protracted crises: A multiscalar cultural political economy perspective. Comparative Education Review, 67(1), 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, S. L., Flores, B. B., Claeys, L., & Sass, D. A. (2017). Consequences of educator stress on turnover: The case of charter schools. In T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, & D. J. Francis (Eds.), Aligning perspectives on health, safety and well-being. Educator stress (pp. 127–155). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuhan, G. C., Nicolau, R. G., & Iliescu, D. (2022). Perceived stress and wellbeing in Romanian teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The intervening effects of job crafting and problem-focused coping. Psychology in the Schools, 59(9), 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collie, R. J. (2023). Teacher well-being and turnover intentions: Investigating the roles of job resources and job demands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2015). Teacher well-being. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(8), 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, L., Bauman, A., Peralta, L. R., Okely, A. D., & Phongsavan, P. (2022). Characteristics and effectiveness of physical activity, nutrition and/or sleep interventions to improve the mental well-being of teachers: A scoping review. Health Education Journal, 81(2), 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T. (2017). Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T., Wong, S., & Logan, H. (2021). Early childhood educators’ well-being, work environments and ‘quality’: Possibilities for changing policy and practice. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 46(1), 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Lema, M. L., Rossi, L., & Soncin, M. (2023). Teaching away from school: Do school digital support influence teachers’ well-being during COVID-19 emergency? Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 11(10), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1(2), 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilekçi, Ü., & Limon, I. (2020). The mediator role of teachers’ subjective well-being in the relationship between principals’ instructional leadership and teachers’ professional engagement=Okul müdürlerinin ögretimsel liderlik davranislari ile ögretmenlerin mesleki adanmisliklari arasindaki iliskide öznel iyi olusun araci rolü. Educational Administration: Theory & Practice, 26(4), 743–798. [Google Scholar]

- Dreer, B. (2022). Teacher well-being: Investigating the contributions of school climate and job crafting. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2044583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreer, B. (2023). On the outcomes of teacher wellbeing: A systematic review of research. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1205179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreer, B., & Gouasé, N. (2022). Interventions fostering well-being of schoolteachers: A review of research. Oxford Review of Education, 48(5), 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Seligman, M. E. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloff, I., & Dittrich, A.-K. (2021). Understanding general pedagogical knowledge influences on sustainable teacher well-being: A qualitative exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(5), 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, M., Kuhbandner, C., & Hilbert, S. (2022). Teacher well-being: Teachers’ goals and emotions for students showing undesirable behaviors count more than that for students showing desirable behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 842231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, H. B., Walter, H. L., & Ball, K. B. (2023). Methods used to evaluate teacher well-being: A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 60(10), 4177–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D. E., Morinaj, J., Guias, D., & Hobusch, U. (2022). Newly qualified teachers’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Testing a social support intervention through design-based research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 873797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, M. G., & Hardin, C. (2015). A “hot” mess: Unpacking the relation between teachers’ beliefs and emotions. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 230–246). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Green, F. (2021). British teachers’ declining job quality: Evidence from the skills and employment survey. Oxford Review of Education, 47(3), 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T., Mercer, S., MacIntyre, P., Talbot, K., & Banga, C. A. (2023). Understanding language teacher wellbeing: An ESM study of daily stressors and uplifts. Language Teaching Research, 27(4), 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, Y. (2022). The correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions and tolerance and psychological well-being. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 9(3), 1307–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Hartcher, K., Chapman, S., & Morrison, C. (2023). Applying a band-aid or building a bridge: Ecological factors and divergent approaches to enhancing teacher wellbeing. Cambridge Journal of Education, 53(3), 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., Beltman, S., & Mansfield, C. (2021). Teacher wellbeing and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educational Research, 63(4), 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T., & Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinecke-Müller, M. (2021). Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie: Überzeugungssysteme, Glaubenssysteme. Dorsch Hogrefe. Available online: https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/ueberzeugungssystem-glaubenssystem#search=8925ddc3370e00384d552125c1e9c1c6&offset=0 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Herzberg, F. (1987). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review, 65, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hester, W. T. (2020). The whole teacher: Growing educator resilience and well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education]. RIS. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshberg, M. J., Frye, C., Dahl, C. J., Riordan, K. M., Vack, N. J., Sachs, J., Goldman, R., Davidson, R. J., & Goldberg, S. B. (2022). A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone-based well-being training in public school system employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(8), 1895–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jõgi, A.-L., Aulén, A.-M., Pakarinen, E., & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2023). Teachers’ daily physiological stress and positive affect in relation to their general occupational well-being. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, N. E. (2020). A close look at teachers’ lives: Caring for the well-being of elementary teachers in the US. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbe, R. H., & Burnett, M. S. (1991). Content-analysis research: An examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 18, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhsari, M., Chen, J., & Baniasad, S. (2023). Multilevel analysis of teacher professional well-being and its influential factors based on TALIS data. Research in Comparative and International Education, 18(3), 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. O., Lacey, H. M., van Valkenburg, S., McGinnis, E., Huber, B. J., Benner, G. J., & Strycker, L. A. (2023). What about me? The importance of teacher social and emotional learning and well-being in the classroom. Beyond Behavior, 32(1), 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B. B. (2015). The developement of teachers’ beliefs. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 48–65). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W., Song, H., & Sun, R. (2022). Can a professional learning community facilitate teacher well-being in China? The mediating role of teaching self-efficacy. Educational Studies, 48(3), 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S. J., Snyder, C. R., Watson, D., & Naragon, K. (Eds.). (2009). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, F., & Price, D. (2015). Nurturing wellbeing development in education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the literature. University of Adelaide. Available online: https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/Resources/WAL%204%20[Open%20Access]/Teacher%20Wellbeing%20A%20Review%20of%20The%20Literature%20Faye%20McCallum%202017.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Mendoza, N. B., King, R. B., & Haw, J. Y. (2023). The mental health and well-being of students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Combining classical statistics and machine learning approaches. Educational Psychology, 43(5), 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalipay, M. J. N., King, R. B., Mordeno, I. G., & Wang, H. (2022). Are good teachers born or made? Teachers who hold a growth mindset about their teaching ability have better well-being. Educational Psychology, 42(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenzein, R., & Döring, S. A. (2009). Ten perspectives on emotional experience: Introduction to the special issue. Emotion Review, 1(3), 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, T. L., Long, A. C. J., & Cook, C. R. (2015). Assessing teachers’ positive psychological functioning at work: Development and validation of the teacher subjective wellbeing questionnaire. School Psychology Quarterly: The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 30(2), 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2000). Broad dispositions, broad aspirations: The intersection of personality traits and major life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(10), 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandilos, L. E., & DiPerna, J. C. (2022). Initial development and validation of the measures of stressors and supports for teachers (MOST). Assessment for Effective Intervention, 47(4), 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F., & Cramer, C. (2022). Towards a conceptual systematic review: Proposing a methodological framework. Educational Review, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being (1. Free Press hardcover ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skott, J. (2015). The promises, problems, and prospects of research on teachers’ beliefs. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 13–30). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, L. C., & Ladd, H. F. (2020). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. AERA Open, 6(1), 2332858420905812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. E., & Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers’ emotions and teaching: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4), 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thönes, K. V. (2024). Glück im Lehrerberuf (1. Auflage). In klinkhardt forschung. Studien zur Professionsforschung und Lehrkräften. Julius Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Travers, C. (2017). Current knowledge on the nature, prevalence, sources and potential impact of teacher stress. In T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, & D. J. Francis (Eds.), Aligning perspectives on health, safety and well-being. Educator stress (pp. 23–54). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Horn, J. E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2004). The structue of occupational well-being: A study among Dutch teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viac, C., & Fraser, P. (2020). Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis. OECD Education Working Paper No. 213. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, T., & Kunter, M. (2013). Teachers’ general pedagogical/psychological knowledge. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers (pp. 207–227). Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2019). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D., & Naragon, K. (2009). Positive affectivity: The disposition to experience positive emotional states. In S. J. Lopez, C. R. Snyder, D. Watson, & K. Naragon (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 206–216). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2015). A motivational analysis of teachers’ beliefs. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), Educational psychology handbook series. International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 191–211). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- White, M. D., & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends, 55(1), 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A. S., & Grainger, P. R. (2020). Teacher wellbeing in remote Australian communities. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 45(5), 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

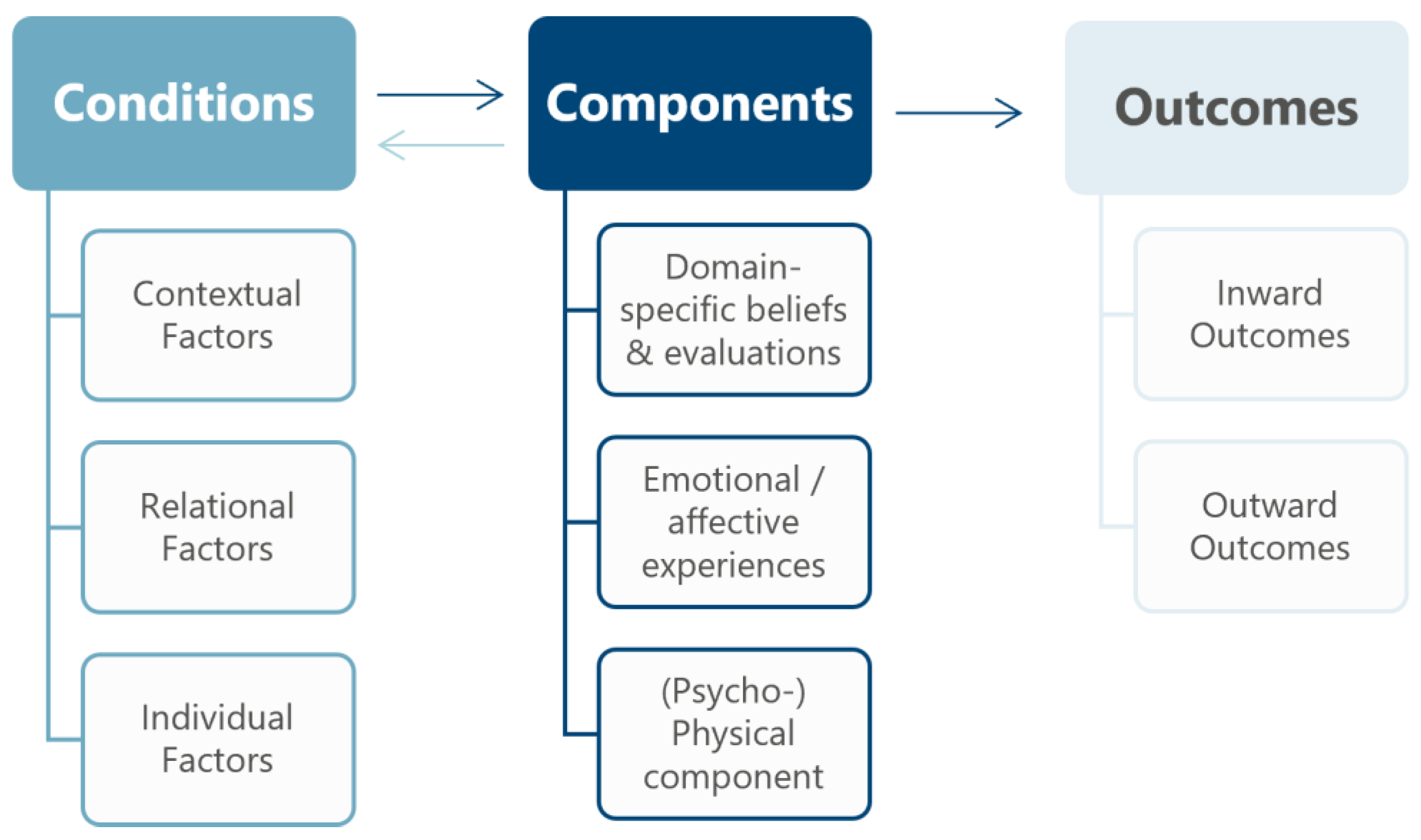

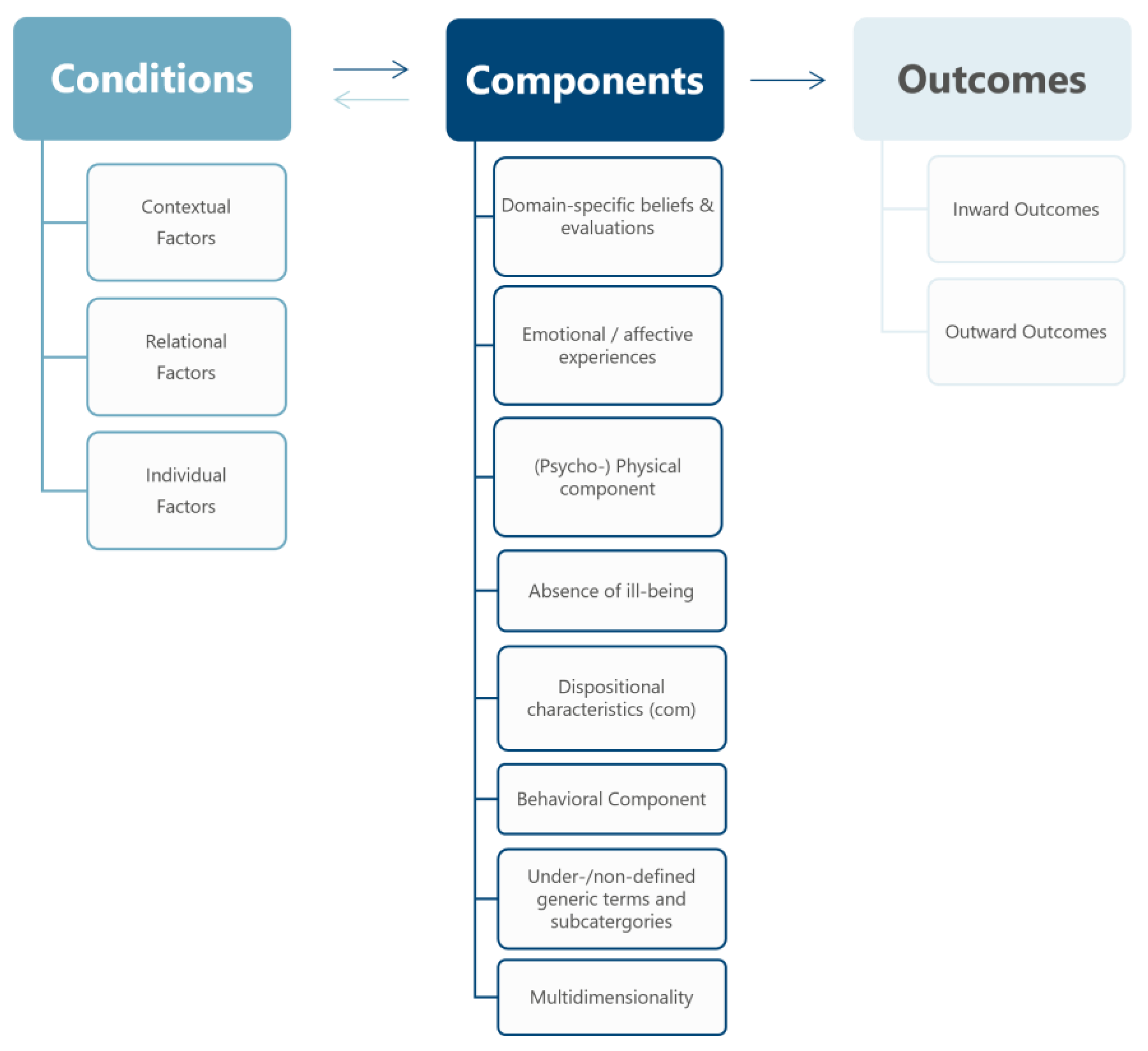

| Perspective | Definition of Perspective | Category | Definition of Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Conditions represent the circumstances under which teachers are most likely to develop well-being, encompassing all factors that are hypothesized to influence or be related to TWB. | Contextual Factors | Contextual factors include all the circumstances that make up the environment in which a teacher works. Therefore, they influence teachers’ well-being but are mainly beyond the teacher’s control. Regarding Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological framework, contextual factors can be located in the exo-, macro-, and chronosystems of teacher well-being (Berger et al., 2022; Hartcher et al., 2023). |

| Relational Factors | Relational factors involve all circumstances that arise in the interaction and relationships with other individuals (microsystem) or groups of individuals (mesosystem) (Berger et al., 2022; Hartcher et al., 2023). | ||

| Individual Factors | Individual factors include the elements influencing teachers’ well-being that are located within a teacher and are thus under their control, at least to some extent (Berger et al., 2022; Hartcher et al., 2023). | ||

| Components | Components encompass all constructs that serve as descriptive labels of well-being as a salient feature in the experience and behavior of a teacher or that are declared to be part of an internal state of well-being. | Domain-Specific Beliefs and Evaluations | Domain-specific beliefs and evaluations refer to relatively enduring examinations and overall appraisals of particular aspects (domains) of a teacher’s life, often derived from past experiences. Beliefs/evaluations include affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). |

| Emotional/Affective Experiences | Emotional/affective experiences describe how a person perceives events, situations, or other people and all emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that a person can express within a specific context (Reisenzein & Döring, 2009). | ||

| (Psycho-)Physical Components | Psycho-physical components describe functional indicators in bodily systems that may be caused by psychological factors (American Psychological Association, 2018). | ||

| Outcomes | Outcomes cover allimplications of teachers’ occupational well-being on other constructs. | Inward Outcomes | Inward outcomes pertain to all implications of TWB on factors that lie within the individual teacher as a person. |

| Outward Outcomes | Outward outcomes encompass all effects of TWB that pertain to the environment and systems surrounding teachers. |

| Category | Subcategory | Definition of Subcategory | Dimension | Definition of Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual Factors | System-level conditions | National structures and systems in which teachers live and work and which therefore indirectly influence TWB (Viac & Fraser, 2020). These factors are located in the exo- and macrosystems (Berger et al., 2022). | Country | Factors influencing TWB due to the country they live and work in. |

| Policy system | Any laws, regulations, and guidelines that shape teachers’ environment and therefore their well-being. | |||

| (Socio-)economic conditions | All factors influencing TWB that depend on the economical and societal background. | |||

| Educational system | The organizing principles and structures of formal education. | |||

| Socio-cultural conditions | All factors influencing TWB that depend on the society and its culture, including expectations on and perceptions of the teaching profession in society. | |||

| School-level conditions | All non-economic factors influencing teachers’ employment and well-being that occur in a school and may vary from school to school. | School leadership | All factors that influence TWB and originate from the school’s principal and the school management team. | |

| Well-being support from school | The measures a school undertake to enhance TWB. | |||

| School quality | The assessment of how good a school is, including its resources. | |||

| School climate and culture | The ambience as well as the shared values and beliefs of the school community. | |||

| Job-level conditions | All non-social factors that directly affect teachers’ jobs and vary from teacher to teacher. | Training and professional development | A teachers’ education, encompassing initial teacher training as well as trainings and interventions throughout teachers’ working lives (Viac & Fraser, 2020). | |

| Classroom environment | All factors influencing TWB that are located in the classroom. | |||

| Pandemic/COVID-19 | All circumstances caused by a widespread disease. | School closures | The exceptional regulation that schools must be closed in order to maintain safety and withstand the further spread of a highly contagious disease. | |

| Relational Factors | (no further distinction) 1 | |||

| Individual Factors | Domain-specific beliefs and evaluations (in) 2 | Relatively enduring examinations and overall appraisals of or associations with particular aspects (domains) of a teacher’s life, often derived from past experiences, that influence TWB. Beliefs/evaluations include affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). | Work-specific beliefs and evaluations (in) | Beliefs and evaluations pertaining to teachers’ work lives. |

| Self-specific beliefs and evaluations (in) | Beliefs and evaluations pertaining to oneself, thus describing teachers’ self-concept and self-worth. | |||

| Life-specific beliefs and evaluations (in) | Beliefs and evaluations pertaining to teachers’ personal lives. | |||

| Knowledge and competencies | The scope of teachers’ understanding or information and their skill set, especially when applied to different problems and situations (American Psychological Association, 2018), that influence TWB. | Stress management skills (in) | Teachers’ understanding or information regarding stress, especially teachers’ ability to deal with stressful events. | |

| Pedagogical–psychological knowledge | Teachers’ understanding, information, and ability to create optimal teaching and learning situations (Voss & Kunter, 2013). | |||

| Social–emotional competence | The ability to understand and regulate one’s emotions and to interact with others in a positive way. | |||

| Health status (in) | The condition of one’s mind, body, and spirit, the idea being freedom from illness, injury, pain, and distress (American Psychological Association, 2018) which influences TWB. | Burnout (in) | A state of physical, emotional, or mental exhaustion caused by prolonged overload (American Psychological Association, 2018). | |

| Stress (in) | The physiological or psychological response to internal or external stressors (American Psychological Association, 2018). | |||

| Mental health | A state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life (American Psychological Association, 2018). | |||

| Emotional/affective experience (in) | The subjective perceptions of events, situations, or other people and all emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that a person can express within a specific context, which, as a condition, influence TWB. This involves emotion states as well as affective traits (Reisenzein & Döring, 2009). | Positive emotions/affect (in) | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that are pleasant and desired that influence TWB. | |

| Negative emotions/affect (in) | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that are unpleasant and undesired that influence TWB. | |||

| Dispositional characteristics (in) | Teachers’ relatively consistent behavioral, cognitive, or affective patterns that are unique to each person and that influence TWB (Lopez et al., 2009; Roberts & Robins, 2000; Watson & Naragon, 2009). | Personality | The enduring configuration of characteristics and behavior that comprises an individual’s unique adjustment to life, including major traits, interests, drives, values, self-concept, abilities, and emotional patterns (American Psychological Association, 2018). | |

| Psychological principle of bad is stronger than good | The psychological phenomenon that events perceived as bad or undesirable are more rememberable and overshadow events that are perceived as desirable or good (Forster et al., 2022). | |||

| Demographics | Statistical characteristics of people or a group of people that influence TWB. | Socio-economic status | A person’s status in the society, including their economic situation. | |

| Behavior and lifestyle (in) | Objectively and introspectively observable activities and ways of life (American Psychological Association, 2018), which, as conditions, influence TWB. | Behavior at work (in) | All objectively and introspectively observable activities a teacher undertakes at work. | |

| Lifestyle behavior (in) | All objectively and introspectively observable activities that shape teachers’ everyday life and define their way of living. |

| Category | Subcategory | Definition of Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional/affective experiences (com) 1 | Absence of negative affect (com) | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that are unpleasant and undesired and not specific to a certain environment or situation. |

| Presence of positive affect (com) | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that are pleasant and desired and not specific to a certain environment or situation. | |

| Emotional/affective experiences in job | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that a person can express with reference to their job. | |

| Emotional/affective experiences in relationships | All emotions, feelings, sentiments, or moods that a person can express to describe their connection to or interaction with other people. | |

| Domain-specific beliefs and evaluations (com) | Life-specific beliefs and evaluations (com) | Relatively enduring examinations and overall appraisals of or associations with teachers’ lives, often derived from past experiences, thereby including affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). |

| Work-specific beliefs and evaluations (com) | Relatively enduringl examinations and overall appraisals of or associations with teachers’ work, often derived from past experiences, thereby including affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). | |

| Relation-specific beliefs and evaluations | Relatively enduring examinations and overall appraisals of or associations with teachers’ relationships, their quality, and depth, thereby including affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). | |

| Self-specific beliefs and evaluations (com) | Relatively enduring and examinations and overall appraisals of or associations of oneself, describing teachers’ self-concept and self-perception, thereby including affective as well as cognitive components (Levin, 2015; Skott, 2015). | |

| Absence of ill-being | Low(er) levels of distress (com) | TWB is described through the absence of or fewer experiences of imbalances between demands and resources and better coping with stressors (Viac & Fraser, 2020). |

| Low(er) levels of burnout (com) | TWB is described through the absence of or fewer experiences of exhaustion due to less overexertion. | |

| (Psycho-)physical components | (No further distinction) | |

| Dispositional characteristics (com) | (No further distinction) | |

| Behavioral component (com) | Lifestyle behavior (com) | All objectively and introspectively observable activities that shape teachers’ everyday lives, define their ways of living, and express TWB. |

| Under-/non-defined generic terms and subcategories | Cognitive component | The statement that TWB has a cognitive component or dimension. |

| Positive psychology | A specific field of psychology that examines the positive development of people (Hascher & Waber, 2021) but is used as a synonym for TWB. | |

| Work-related/occupational well-being | Well-being that is related to work life (Green, 2021) but not specified further. | |

| Multidimensionality | (No further distinction) |

| Category | Subcategory | Definition of Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

| Inward outcomes | Self-related inward outcomes | All implications of TWB on the factors that lie within the individual teachers themselves. |

| Job-related inward outcomes | All implications of TWB on the factors that relate to teachers’ beliefs and evaluations regarding their work lives. | |

| Level of stress and burnout (out) | The experience of imbalances between demands and resources as a consequence of the level of TWB (Viac & Fraser, 2020). | |

| Outward outcomes | School/classroom-related outcomes | The effects of TWB that influence the learning environment, classroom processes, and its quality (Viac & Fraser, 2020). |

| Relational outcomes | All effects of TWB that pertain to teachers’ interactions with other people or groups. | |

| Student-related outcomes | All effects of TWB that influence students. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurrle, L.M.; Warwas, J. Teacher Well-Being—A Conceptual Systematic Review (2020–2023). Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060766

Kurrle LM, Warwas J. Teacher Well-Being—A Conceptual Systematic Review (2020–2023). Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):766. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060766

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurrle, Laura Maria, and Julia Warwas. 2025. "Teacher Well-Being—A Conceptual Systematic Review (2020–2023)" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060766

APA StyleKurrle, L. M., & Warwas, J. (2025). Teacher Well-Being—A Conceptual Systematic Review (2020–2023). Education Sciences, 15(6), 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060766