‘They Started School and Then English Crept in at Home’: Insights into the Influence of Forces Outside the Family Home on Family Language Policy Negotiation Within Polish Transnational Families in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Language Education Policy in Ireland

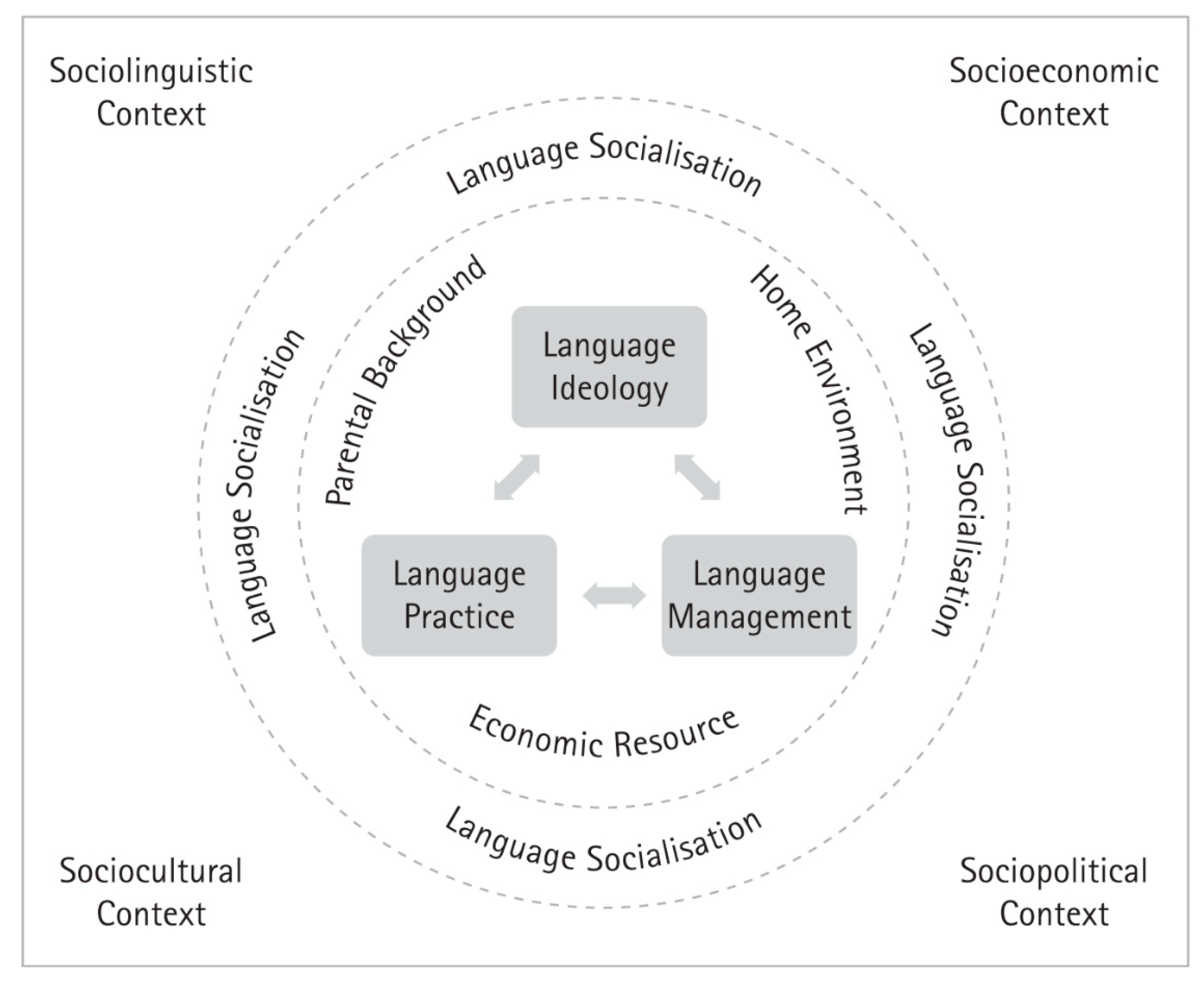

1.2. Family Language Policy and Theoretical Framework

1.3. Language Socialisation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment and Profiles

2.2. Data Collection Methods and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Parents’ Awareness of Their Children Being Socialised into English Language Use

What I find is that when Kuba is with Polish friends, they speak English. This is common I think for kids from Poland who are living here a long time, maybe ten years because of the school, and they are walking around the house speaking English.(II3)

It’s like in English-speaking countries, English is dominant and all the other languages, even the native languages, don’t matter so much. I think it’s because English is the language people speak and you don’t have to learn another language to do well because everybody in the world is learning English.(Mother, Family B)

When they start the primary school and when they make the Irish friends, this is when they speak so much English and then they get used to this more and more and they spend more time with their friends outside the house.(Mother, Family E)

I got advice from preschool for Zuzanna that I should teach her a little bit of English but I refused. I don’t want to teach incorrect English. I see lots of parents doing this and it’s not good. If they would like their children to have some English words, the children will get them themselves because they have to.(Mother, Family D)

You know Zofia’s teacher in junior infants said to me ‘Can you speak English at home so she will learn it more quickly?’ and my answer was ‘No, we will never do this. Polish is our language and they will need the language for when they are with Polish family.’ Also I was thinking our English is not too good for speaking at home.(Father, Family A)

3.2. Children’s Awareness of English Language Importance and Language Practice Preferences

The majority of my life is now in English. Like, the majority of people I talk to, I talk to in English. Therefore, it just becomes the default. Like, it becomes the language I turn to. I know more words in English and I can express myself better in English. I’ve just been here so much longer. So it’s Polish for the home stuff and English for everything else.(Son, Family E)

I don’t really get the opportunity to speak Polish very often since I’m always out with my friends or in school. I honestly find it easier to speak English since my English is more developed than my Polish.(Son, Family E)

Henryk: I think through English.Malgorzata: And in Polish…no?Henryk: When I think in my head, I always picture in English. I never think through Polish. I don’t think I’ll ever think through Polish.Malgorzata: And of course I think through Polish.Henryk: I don’t know where it comes from. I don’t know why I think in English and not Polish. But it doesn’t bother me at all.(Family C)

It’s easier for me to read and write in English. I would choose to read English books quicker. I read to expand my vocabulary and English I use more often in school, so picking English books is more useful to me for vocabulary.(Daughter, Family A)

When it comes to my brothers, I don’t really use too much Polish. Me and Kacper speak about school, friends, games all the time so it’s very difficult to translate all the words in our heads and talk about the things in Polish when we could just go to the easier alternative and speak English.(Son, Family E)

I have travelled around most of Europe and being able to speak English has been an advantage. I believe that English is a very handy and smart language. It is a very useful language and I think it will really help me in the future.(Son, Family E)

I think English will be great for me in the future if I want to work abroad or travel. My cousins in Poland learn English but they are not so fluent and it would be harder for them to communicate with people like in a work space if they ever work abroad but it’ll be easier for me because loads of people speak English around the world.(Daughter, Family A)

3.3. Children’s Experiences of Polish Language Recognition, Use, and Non-Use in School Settings

There were other kids from Poland in my class and we used to talk Polish together during the break but teachers told us to stop speaking Polish and to use English in the class … It felt so weird because I knew what I wanted to say to them in Polish but to try and say the same in English was tricky. The teachers knew I knew Polish but they probably wanted me to learn English since I was living in Ireland and English is the main language here.(Daughter, Family A)

I had to do lots of translation for the teachers when a new Polish child came or when they needed me to help a younger child. If there was a Polish child crying, they came to me and asked me to talk to the young child in Polish to try help them.(Son, Family E)

I’ve a few Polish friends because I went to Polish school and made friends there. Surprisingly, we speak all Polish because if I spoke English, it would be really awkward to hear us speaking English because we are just used to Polish in Polish school … Another Polish friend I have … I speak to him in English because I know him very well since second class of primary school.(Son, Family C)

3.4. Negotiating Family Language Policy

Kamil, because he is here more years than he was in Poland he prefers to communicate in English … In English he can speak better. He says ‘I use English in school so I am more familiar with it’ … You see I know everything he does is in English now. He goes to the movies. They are in English. He goes to school. Everything is in English. He speaks English with many of his friends. He was eight when he left Poland and he is now 18 years old. English is his language I know.(II2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonini, R. (2016). Caught in the middle: Child language brokering as a form of unrecognised language service. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(7), 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bezcioglu-Göktolga, I., & Yagmur, K. (2018). The impact of Dutch teachers on family language policy of Turkish immigrant parents. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 31(3), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1977a). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1977b). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16(6), 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, S., Hagan, M., O’Toole, B., Quinn, F., & Ryan, A. (2009, November 11). English as an additional language in undergraduate teacher education programmes in Ireland: A report on provision in two teacher education colleges. Standing Conference on Teacher Education, North and South, Armagh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2008). Language shift and the family: Questions from the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12(2), 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connaughton-Crean, L., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2017). Home language maintenance and development among first generation migrant children in an Irish primary school: An investigation of attitudes. Journal of Home Language Research, 2(1), 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connaughton-Crean, L., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2024). ‘We are always planning trips to Poland’: The influence of transnational family life on the family language policy of Polish-speaking families in Ireland. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSO. (2017). Summary results. Part 1. Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. (2023). Census of population 2022 profile 1—Population distribution and movements. Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2009). Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy, 8(4), 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2013). Family language policy: Sociopolitical reality versus linguistic continuity. Language Policy, 12(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2018). Family language policy. In J. W. Tollefson, & M. Pérez-Milans (Eds.), Oxford handbook of language policy and planning. OUP. [Google Scholar]

- DES. (2011). Literacy and numeracy for learning and life. The national strategy to improve literacy and numeracy among children and young people 2011–2020. Department of Education and Skills. Available online: http://www.education.ie/en/Schools-Colleges/Information/Literacy-and-Numeracy/Literacy-and-Numeracy-Learning-For-Life.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- DES. (2017). Languages connect, Ireland’s strategy for foreign languages in education, 2017–2026. Department of Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- DES. (2019). Primary language curriculum. Department of Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- DES. (2023). Towards a new literacy, numeracy and digital literacy strategy: A review of the literature. Department of Education (Ireland). [Google Scholar]

- Devine, D. (2005). Welcome to the Celtic tiger? Teacher responses to immigration and increasing ethnic diversity in Irish schools. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 15(1), 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D., & McGillicuddy, D. (2016). Positioning pedagogy—A matter of children’s rights. Oxford Review of Education, 42(4), 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, P. (2007). Second language socialization as sociocultural theory: Insights and issues. Language Teaching, 40(4), 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, P. (2014). Language socialization into Chinese language and “Chineseness” in diaspora communities. In X. L. Curdt-Christiansen, & A. Hancock (Eds.), Learning Chinese in diasporic communities: Many pathways to being Chinese (pp. 13–33). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogle, L. W. (2012). Second language socialization and learner agency. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fogle, L. W. (2013). Parental ethnotheories and family language policy in transnational adoptive families. Language Policy, 12(1), 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogle, L. W., & King, K. A. (2013). Child agency and language policy in transnational families. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 19(0). Available online: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/39b3j3kp (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Kealy, C., & Devaney, C. (2024). Culture and parenting: Polish migrant parents’ perspectives on how culture shapes their parenting in a culturally diverse Irish neighbourhood. Journal of Family Studies, 30(2), 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. A., & Logan-Terry, A. (2008). Additive bilingualism through family language policy: Strategies, identities and interactional outcomes (Vol. 6). Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=571561889002 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Kirwan, D. (2013). From English language support to plurilingual awareness. In D. Little, C. Leung, & P. Van Avermaet (Eds.), Managing diversity in education: Languages, policies, pedagogies. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kropiwiec, K., & King-O Riain, R. C. (2006). Polish migrant workers in Ireland. National Consultative Committee on Racism and Interculturalism (NCCRI). [Google Scholar]

- Kulick, D., & Schieffelin, B. B. (2007). Language Socialization. In A. Duranti (Ed.), A companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 347–368). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, E. (2007). Multilingualism and the family. In P. Auer, & L. Wei (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication (pp. 45–67). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Little, D., & Kirwan, D. (2019). Engaging with linguistic diversity: A study of educational inclusion in an Irish primary school. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Luykx, A. (2005, April 30). Children as socializing agents: Family language policy in situations of language shift. 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2013). A language socialization perspective on knowledge and identity construction in Irish post-primary education. In F. Farr, & M. Moriarty (Eds.), Language learning and teaching. Irish research perspectives (pp. 87–110). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2017). ‘To be like a home extension’: Challenges of language learning and language maintenance—Lessons from the Polish-Irish experience. Journal of Home Language Research, 2, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2019). Language and emotions: A follow-up study of ‘moral allegiances’—The case of Wiktoria. TEANGA, the Journal of the Irish Association for Applied Linguistics, 10, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2020). The multilingual adolescent experience: Small stories of integration and socialization by Polish families in Ireland. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Daid, R. (2011). Glos, voce, coice. Minority language children reflect on the recognition of their first languages in Irish primary schools. In M. Darmody, N. Tyrrell, & S. Song (Eds.), The changing faces of Ireland (pp. 17–33). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, L. C. (2005). Language socialization. In A. Sujoldzic (Ed.), Linguistic anthropology. EOLSS. [Google Scholar]

- NCCA. (2005). Intercultural education in the primary school: Guidelines for Schools. NCCA. [Google Scholar]

- NCCA. (2006). English as an additional language in Irish primary schools: Guidelines for teachers. NCCA. [Google Scholar]

- Nero, S. J. (2005). Language, identities, and ESL pedagogy. Language and Education, 19(3), 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestor, N., & Regan, V. (2011). The new kid on the block. In M. Darmody, N. Tyrrell, & S. Song (Eds.), The changing faces of Ireland (pp. 35–52). Rotterdam: SensePublishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Dhiorbháin, A., Nic Aindriú, S., Connaughton-Crean, L., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2023). It’s more the invisible benefits—Multilingual parents’ experiences of immersion education and their reasons for choosing immersion. Language and Education, 38(5), 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, E. (2008). Underneath the band-aid: Supporting bilingual students in Irish schools. Irish Educational Studies, 27(3), 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, E. (1999). Socialization. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 9(1–2), 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories. In R. Shweder, & R. LeVine (Eds.), Culture theory: Mind, self, and emotion (pp. 276–320). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (2011). The theory of language socialization. In A. Duranti, E. Ochs, & B. B. Schieffelin (Eds.), The Handbook of language socialization (pp. 1–21). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ó hIfearnáin, T. (2007). Raising Children to be Bilingual in the Gaeltacht: Language Preference and Practice. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(4), 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó hIfearnáin, T. (2013). Family language policy, first language Irish speaker attitudes and community-based response to language shift. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(4), 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palviainen, Å., & Boyd, S. (2013). Unity in discourse, diversity in practice: The one person one language policy in bilingual families. In M. Schwartz, & A. Verschik (Eds.), Successful family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction (pp. 223–248). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrak, A. (2019). An evaluation of Polish supplementary schools in Ireland. Teanga, Special Edition, 10, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Revis, M. (2019). A Bourdieusian perspective on child agency in family language policy. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(2), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieffelin, B., & Ochs, E. (1986a). Language socialization. Annual Review of Anthropology, 15(1), 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieffelin, B., & Ochs, E. (1986b). Language socialization across cultures. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. (2010). Family language policy: Core issues of an emerging field. Applied Linguistics Review, 1, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Christmas, C. (2021). ‘Our cat has the power’: The polysemy of a third language in maintaining the power/solidarity equilibrium in family interactions. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(8), 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Christmas, C. (2022). Double-voicing and rubber ducks: The dominance of English in the imaginative play of two bilingual sisters. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(4), 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. (2012). Family language policy—The critical domain. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallen, M., & Kelly-Holmes, H. (2006). ‘I think they just think it’s going to go away at some stage’: Policy and practice in teaching English as an additional language in Irish primary schools. Language and Education, 20(2), 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Mother or Father | Years in Ireland | Current Occupation | No. of Children | Transcript Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gracja | Mother | 9 years | Fitness instructor | 2 (Ages 4 and 6) | FG |

| Marcel | Father | 7 years | Mechanic | 2 (Ages 2 and 5) | FG |

| Daria | Mother | 11 years | Stay-at-home mother | 2 (Ages 4 and 8) | FG |

| Natalia | Mother | 1 year | Hairdresser | 2 (Ages 6 and 12) | FG |

| Patrycja | Mother | 2005–2008 (3 years) 2013–present (4 years) | Stay-at-home mother | 2 (Ages 6 and 12) | FG |

| Karina | Mother | 10 years | Chef | 2 (Ages 1 and 7) | FG |

| Name | Mother or Father | Years in Ireland | Current Occupation | No. of Children | Transcript Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidia | Mother | 17 years | Shop assistant | 2 (Ages 11 and 17) | II1 |

| Wioletta | Mother | 10 years | Childcare worker | 2 (Ages 5 and 18) | II2 |

| Dawid | Father | 11 years | Hotel waiter | 2 (Ages 13 and 16) | II3 |

| Judyta | Mother | 12 years | School secretary | 1 (Age 9) | II4 |

| Martyna | Mother | 10 years | Part-time shop assistant and part-time student | 2 (Ages 1 and 4) | II5 |

| Ewa | Mother | 11 years | Kitchen worker in childcare facility | 2 (Ages 4 and 7) | II6 |

| Family Name | Parent’s Name | Years in Ireland | Child’s Name and Age | Current Education | Languages Spoken in the Home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kowalski (Family A) | Matyas (Father) | 13 years | Zofia Age 16 | Transition Year (Post-primary school) | Polish English |

| Sonia (Mother) | 11 years | Agata Age 13 | Second year (Post-primary school) | ||

| Lewandowski (Family B) | Hanna (Mother) | 3 years | Ola Age 3 | Preschool | Polish |

| Kropkowska (Family C) | Oskar (Father) | 13 years | Henryk Age 17 | Fifth year (Post-primary school) | Polish English |

| Malgorzata (Mother) | 12 years | ||||

| Mazur (Family D) | Jakub (Father) | 10 years | Zuzanna Age 7 (born in Ireland) | First class (Primary school) | Polish English |

| Aneta (Mother) | 10 years | Maja Age 5 (born in Ireland) | Junior infants (Primary school) | ||

| Nowak (Family E) | Bozena (Mother) | 13 years | Kacper Age 16 | Transition Year (Post-primary school) | Polish English |

| Filip Age 14 | Second year (Post-primary school) | ||||

| Bartek (Father) | 12 years | Szymon Age 11 | Fourth class (Primary school) | ||

| Antoni Age 5 | Junior infants (Primary school) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Connaughton-Crean, L.; Ó Duibhir, P. ‘They Started School and Then English Crept in at Home’: Insights into the Influence of Forces Outside the Family Home on Family Language Policy Negotiation Within Polish Transnational Families in Ireland. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060732

Connaughton-Crean L, Ó Duibhir P. ‘They Started School and Then English Crept in at Home’: Insights into the Influence of Forces Outside the Family Home on Family Language Policy Negotiation Within Polish Transnational Families in Ireland. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):732. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060732

Chicago/Turabian StyleConnaughton-Crean, Lorraine, and Pádraig Ó Duibhir. 2025. "‘They Started School and Then English Crept in at Home’: Insights into the Influence of Forces Outside the Family Home on Family Language Policy Negotiation Within Polish Transnational Families in Ireland" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060732

APA StyleConnaughton-Crean, L., & Ó Duibhir, P. (2025). ‘They Started School and Then English Crept in at Home’: Insights into the Influence of Forces Outside the Family Home on Family Language Policy Negotiation Within Polish Transnational Families in Ireland. Education Sciences, 15(6), 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060732