From Picturebooks to Play: Dialogic Pedagogy for Cultivating Agency and Social Awareness in Young Learners

Abstract

1. Introduction

“If we had empathy and someone saw that someone else is being mean, we could stick up for them (the victim) and say stop being mean to them because they don’t like it.”(Brittany)

“If everyone in the world had empathy, people would stop doing mean things.”(Eli)

2. Literacy as a Social Act

3. Making Meaning Using Picturebooks

4. Drama- and Play-Based Pedagogies

5. Conceptual and Theoretical Frameworks

5.1. Sociocultural Theory

5.2. Critical Literacy Inquiry

5.3. Dialogic Pedagogy as a Framework for Empathy and Inquiry

6. Methods and Materials

7. Context and Participants

8. Procedures

9. Overview of Curricular Engagements

9.1. Picturebook Read-Alouds

9.2. Sample Activity Plan Using Picturebooks and Drama

- Objectives:

- Develop students’ ability to recognize and discuss empathy;

- Engage students in dramatic play to explore different perspectives;

- Encourage reflection through writing and group discussions.

- Read-Aloud and Discussion (20 min)

- ○

- The teacher reads aloud, The Invisible Boy, by Trudy Ludwig.

- ○

- Students discuss the main character’s feelings and experiences, guided by the following questions:

- ▪

- How does Brian feel throughout the story?

- ▪

- What changes for Brian by the end?

- ▪

- Have you ever felt invisible? How did that experience make you feel?

- Dramatic Play (20 min)

- ○

- Students participate in a “Hot Seating” activity, where one student plays the role of Brian, and others ask him questions about his experiences.

- Writing Reflection (20 min)

- ○

- Students write a short response from Brian’s perspective: “How did it feel to be invisible? What could others do to make you feel included?”

- ○

- Students share their responses in small groups.

- Classroom Discussion (15 min)

- ○

- The teacher facilitates a final discussion about empathy and how students can apply these ideas to their daily interactions.

10. Data Analysis

10.1. Thematic Analysis

10.2. Critical Literacy Framework

11. Researcher Positionality

12. Results and Key Themes

13. Student Agency and Dialogic Engagement

One student stated, “You can’t play Peter Pan. He isn’t black.”

Ella first said, “That’s kinda rude!” then added, “That’s racist.”

Gary said, “Bad, because I don’t like it when people call me racist,”

Ella interjected, “Peter Pan may be white, but if she (Amazing Grace) puts her mind to it, she can be anything she wants, not due to her skin color but with her imagination. She can imagine. She doesn’t care if she’s black or not.”

Eli explained, “The racist part was whenever Natalie said you can’t be Peter Pan ‘cause you’re black and Peter Pan is white. That’s kind of racist.”

Ella affirmed, “That’s pretty racist!”

Jason, who had been sitting quietly, said, “I don’t know what racist means.” Brittany offered, “Racist means being mean because of skin color.”

Lila added, “That’s mean.”

14. Fostering Inclusivity Through Collaborative Inquiry

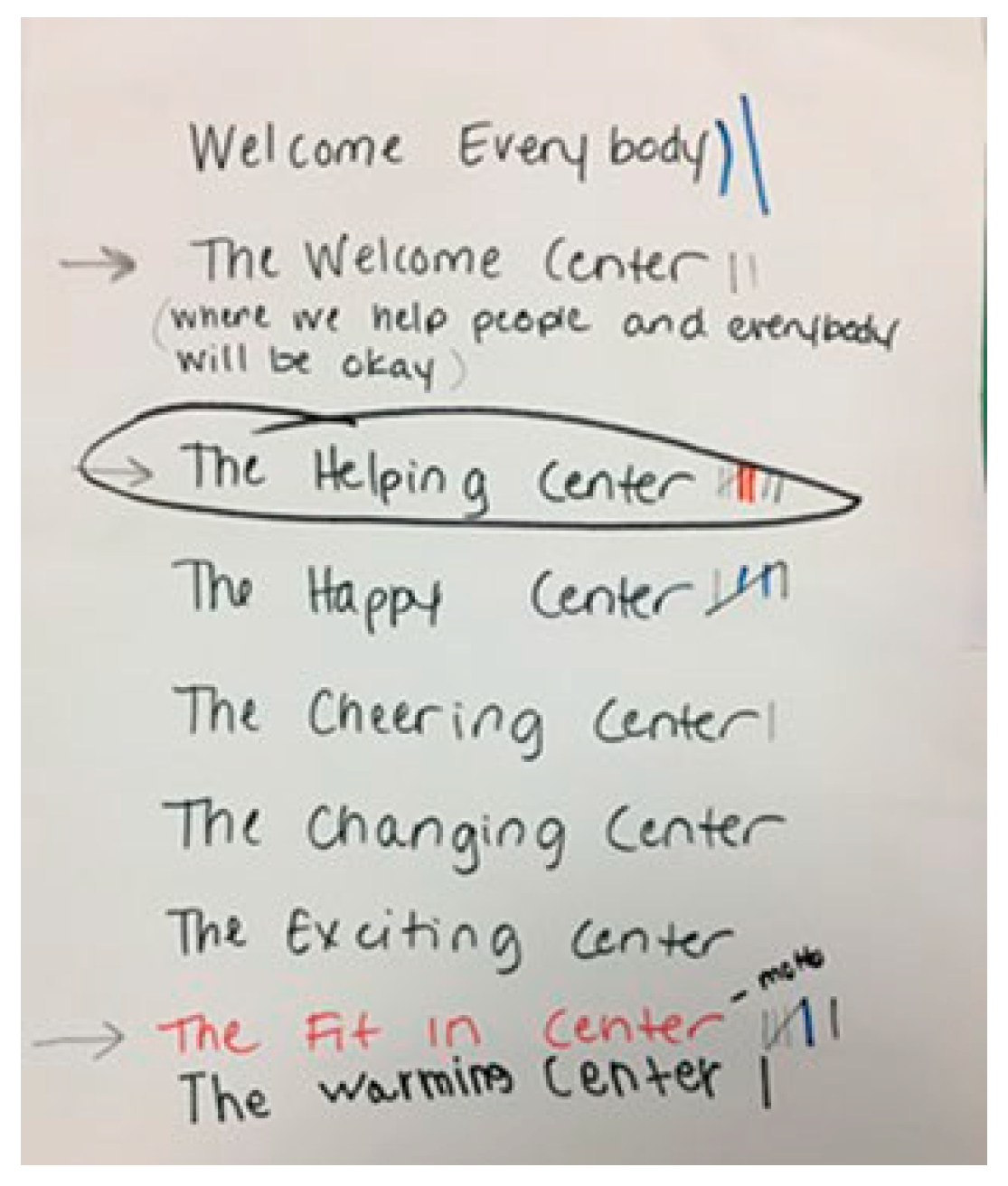

14.1. Conducting Research

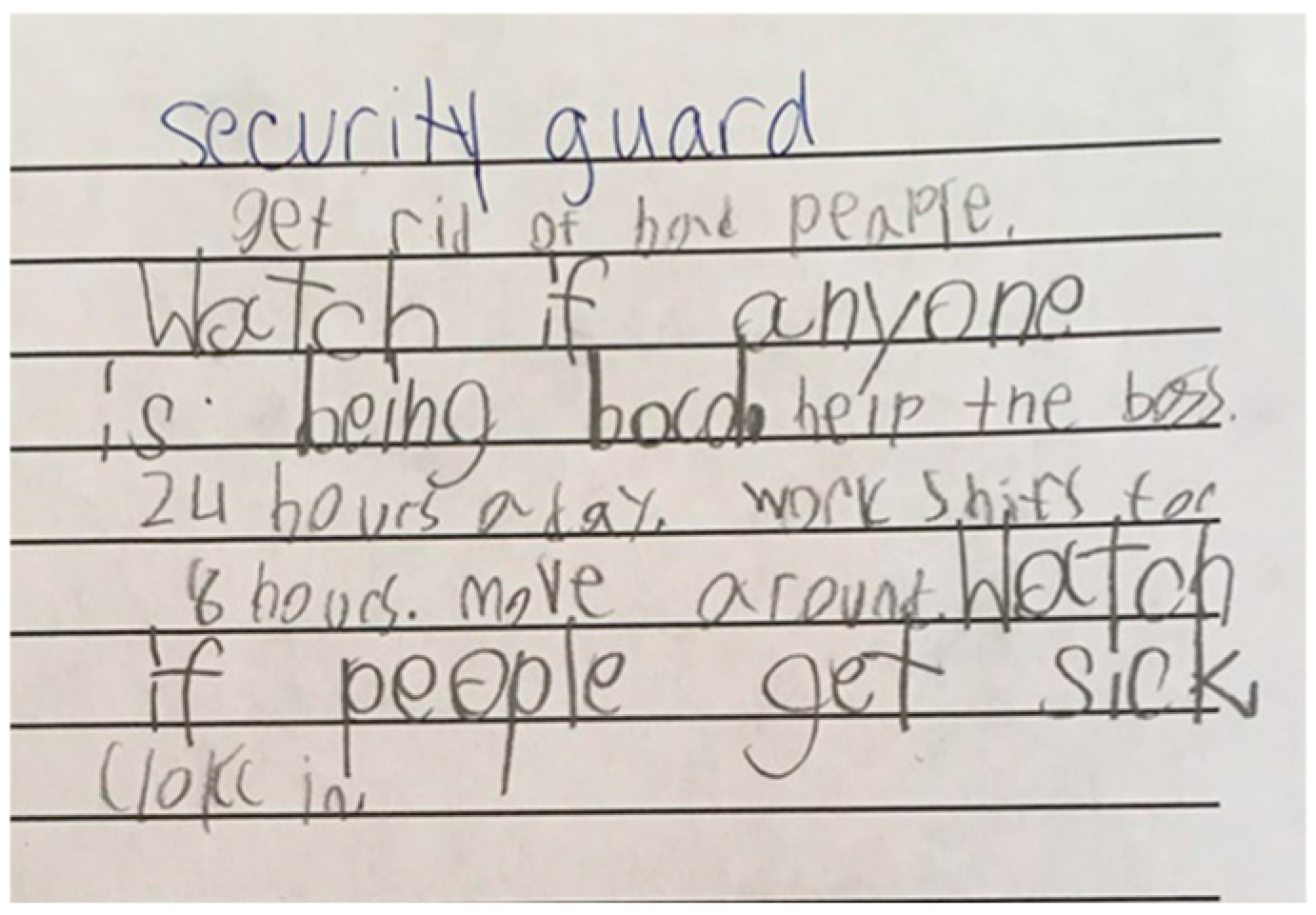

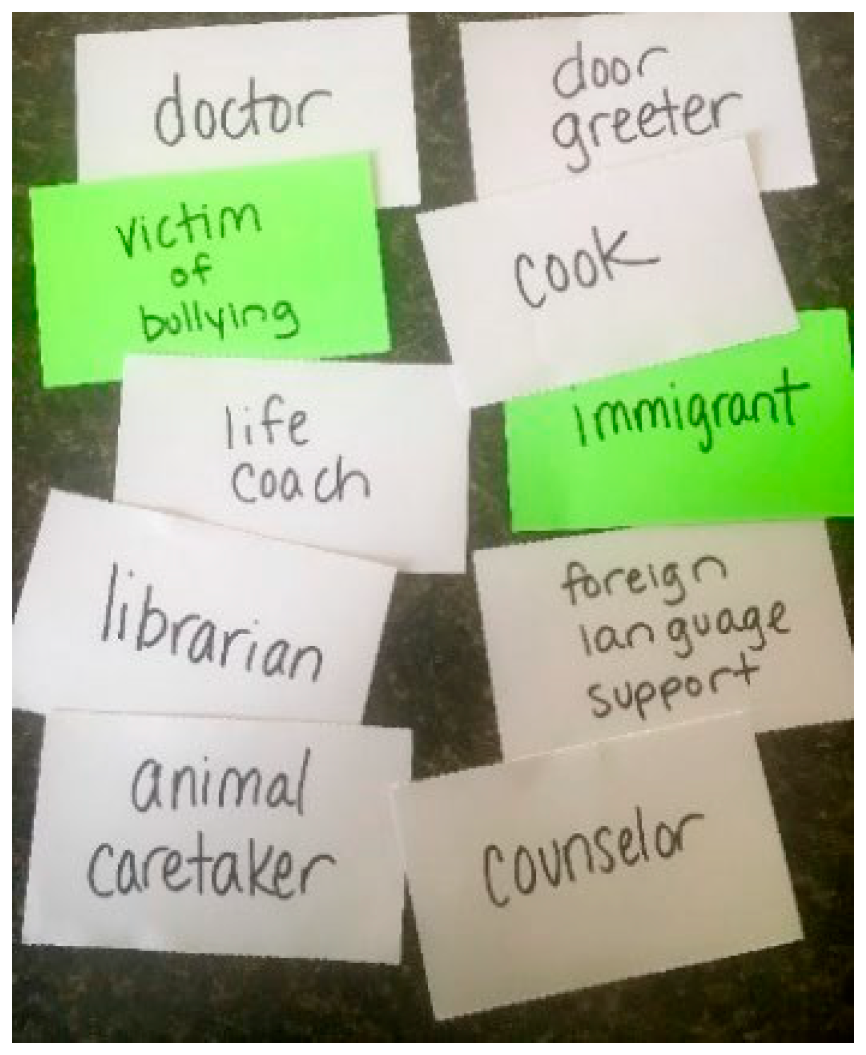

14.2. Creating Jobs and Job Descriptions for the Helping Center

15. Empathy Development: From Dialogue to Action

Ella: “The best thing about it was you get to imagine what you would do and if it was true.”

Me: “How can what we’ve talked about with empathy carry over into your life outside of school or when you move to a new school?”

Ella: “I think, um, at my new school I’d actually teach them about empathy and say I learned about it at my old school.”

Me: “Oh. What would you teach them?”

Ella: “Um, about how, um, we learned all this stuff, and agents for change, and all this cool stuff we did.”

Me: “I’m curious to know if you think people should learn about other people’s perspectives?”

Ella: “Yeah.”

Me: “Why?”

Ella: “I think that would be something great in the world. So, if you like… so you know how you only see your perspective, what if you could see out of other people’s eyes and be them for a day.”

Me: “How would that make the world different?”

Ella: “It would, um, change the way they would see and feel about the person that they’re seeing their eyes through.”

Me: “Is that a good thing…a bad thing…what do you think?”

Ella: “Um, I think that it would be a good thing because then if everybody was able to look through the person’s eyes that they dislike or that they don’t really like that much, I think they’d change because some people could be under trauma, they could be under anything bad and you might actually want to care for that person.”

16. Discussion and Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, R. J. (2008). Towards dialogic teaching (4th ed.). Dialogos. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanič, R. (2000). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, G., & Garvis, S. (2019). Theorizing compassion and empathy in educational contexts: What are compassion and empathy and why are they important? In G. Barton, & S. Garvis (Eds.), Compassion and empathy in educational contexts. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Boelts, M., & Jones, N. (2009). Those shoes. Candlewick Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bomer, R., & Bomer, K. (2001). For a better world: Reading and writing for social action. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, D. (1985). Imaginary gardens with real toads: Reading and drama in education. Theory into Practice, 24, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, D. (1994). Story drama: Reading, writing and roleplaying across the curriculum. Pembroke Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, C. (2020). Gender disrupted during storytime: Critical literacy in early childhood. Journal of Childhood Studies, 45(4), 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L., & Whitney, E. (2009). Walking in their shoes: Using multiple-perspective texts as a bridge to critical literacy. The Reading Teacher, 62(6), 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, B., Thomson, P., & Wells, M. (2001). Critical literacy finds a “place”: Writing and social action in a low-income Australian grade 2/3 classroom. The Elementary School Journal, 101, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B. (2011). Empathy in education: Engagement, values and achievement. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, P. A., Roberts, S. K., & Zygouris-Coe, V. (2019). Addressing 21st century crises through children’s literature: Picturebooks as partners for teacher educators. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 40(1), 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research. planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, N. (2021). Kittens, blankets and seaweed: Developing empathy in relation to language learning via children’s picturebooks. Children’s Literature in Education, 52, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *de la Peña, M. (2015). Last stop on Market Street. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Deliman, A. (2021). Picturebooks and Critical Inquiry: Tools to Re(imagine) a More Inclusive World. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, 59(3), 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliman, A., & Breitenstein, J. (2022). Nurturing meaningful student agency: A kindergarten teacher supports beginning readers using wordless and post-modern picturebooks. The Dragon Lode, 40(2), 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston, B. (2007). Mission to mars: Using drama to make classrooms more inclusive for the language and literacy learning of children with disabilities. Language Arts, 84(4), 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Groves, C. (2023). Dialogic pedagogies. In Oxford handbook of research in education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth, E. (1989). Why doesn’t this feel empowering? Working through the repressive myths of critical pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review, 59(3), 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, G. (2016). Reader response and embodied performance: Body-poems as performative response and performativity. In G. Enriquez, E. Johnson, S. Kontovourki, & C. A. Mallozzi (Eds.), Literacies, learning, and the body: Putting theory and research into pedagogical practice (pp. 41–56). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farini, F., Baraldi, C., & Scollan, A. (2023). This is my truth, tell me yours: Positioning children as authors of knowledge through facilitation of narratives in dialogic interactions. International Journal of Student Voice, 5(1), 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, T. K. (2018). Responsive play: Creating transformative classroom spaces through play as reader response. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 20(2), 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, T. K. (2020). Children’s critical reflections on gender and beauty through responsive play in the classroom context. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(6), 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E., & Short, K. (2021). Enacting empathy through international literature of young people. Voices from the Middle, 29(1), 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1990). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carrión, R., López de Aguileta, G., Padrós, M., & Ramis-Salas, M. (2020). Implications for Social Impact of Dialogic Teaching and Learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P. W., & Parker, T. S. (2018). Young children’s picture-books as a forum for the socialization of emotion. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(3), 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts and social change. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Harste, J. C. (2014). The art of learning to be critically literate. Language Arts, 92(2), 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, D., & Bolton, G. M. (1995). Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach to education. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- *Hoffman, M. (1991). Amazing Grace. Dial Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- *Hoose, P., & Hoose, H. (1999). Hey, little ant. Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, J. (2018). “The soldiers came to the house”: Young children’s responses to the colour of home. Children’s Literature in Education, 49, 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52(2), 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janks, H. (2009). Literacy and power. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Is low empathy related to bullying after controlling for individual and social background variables? Journal of Adolescence, 34, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Khan, R. (2010). Big red lollipop. Viking Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. Y., & Wilkinson, I. A. G. (2019). What is dialogic teaching? Constructing deconstructing, and reconstructing a pedagogy of classroom talk. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 125(21), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krznaric, R. (2014). Empathy: Why it matters, and how to get it. Tarcher. [Google Scholar]

- Kuby, C. R., & Vaughn, M. (2015). Young children’s identities becoming: Exploring agency in the creation of multimodal literacies. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(4), 433–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lain, S. (2019). Picture books teach empathy and much more. New Jersey English Journal, 8(6), 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Le, M. (2018). Drawn together. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Leland, C. H., Harste, J. C., & Huber, K. R. (2005). Out of the box; critical literacy. Language Arts, 82(4), 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, C. H., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. (2013). Teaching children’s literature: It’s critical! Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- *Levison, C. (2017). The youngest marcher: The story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a young civil rights activist. Atheneum Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. (2001). Literary practices as social acts: Power, status and cultural norms in the classroom. L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Lindstrom, C. (2020). We are water protectors. Roaring Brook Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Ludwig, T. (2013). The invisible boy. Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Lyle, S. (2008). Dialogic teaching: Discussing theoretical contexts and reviewing evidence from classroom practice. Language and Education, 22, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martello, J. (2001). Drama: Ways into critical literacy in the early childhood year. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 24(3), 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- *Martinez-Neal, J. (2018). Alma and how she got her name. Candlewick. [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. (2016). Literature and the young child: Engagement, enactment, and agency from a sociocultural perspective. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(4), 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C. (2004). The construction of drama worlds as literary interpretation of Latina feminist literature. Research in Drama Education, 9(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomerie, D., & Ferguson, J. (1999). Bears don’t need phonics: An examination of the role of drama in laying the foundations for critical thinking in the reading process. Research in Drama Education, 4(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Muhammad, I. (2019). The proudest blue: A story of hijab and family. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Muspratt, S., Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1997). Constructing critical literacies: Teaching and learning textual practice. Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, D. S., & Susanto, S. (2021). Using drama in EFL classroom for exploring students’ knowledge and learning. English Review: Journal of English Education, 9(2), 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newstreet, C., Sarker, A., & Shearer, R. (2018). Teaching empathy: Exploring multiple perspectives to address islamophobia through children’s literature. The Reading Teacher, 72(10), 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Noble Maillard, K. (2019). Fry bread: A Native American family story. Roaring Brook Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A relational approach to ethics & moral education (2nd ed.). updated. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L., Norris, J., White, D., & Moules, N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C. (1995). Drama worlds: A framework for process drama. Heineman. [Google Scholar]

- Papen, U., & Peach, E. (2021). Picture books and critical literacy: Using multimodal interaction analysis to examine children’s engagements with a picture book about war and child refugees. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 44(1), 61–74. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.743008380052774 (accessed on 20 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- *Paul, M. (2015). One plastic bag: Isatou Ceesay and the recycling women of the Gambia. Millbrook Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, P. G. (2015). Teaching and learning in a diverse world. Multicultural education for young children. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, M. K., & Morrow, L. M. (2021). The contribution of play experiences in early literacy: Expanding the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S239–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Roberts, J. (2018). On our street: Our first talk about poverty. Orca Book Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem. Southern Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, D. W. (2007). Bringing books to life: The role of book-related dramatic play in young children’s literacy learning. In K. Roskos, & J. Christie (Eds.), Play and literacy in early childhood: Research from multiple perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 37–63). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- *Saied Méndez, Y. (2019). Where are you from? HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sornson, R. (2013). Stand in my shoes: Kids learning about empathy. Love and Logic. [Google Scholar]

- *Street, B. (2003). What’s “new” in new literacy studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 5(2), 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Suttie, J. (2021). How small moments of empathy affect your life. Greater Good Magazine: Science-Based Insights for a Meaningful Life. Available online: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_small_moments_of_empathy_affect_your_life (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Taylor, S. V., & Leung, C. B. (2019). Multimodal literacy and social interaction: Young children’s literacy learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trout, J. D. (2009). Why empathy matters: The science and psychology of better judgement. Penguin Group. [Google Scholar]

- Tschida, C., Ryan, C., & Ticknor, A. (2014). Building on windows and mirrors: Encouraging the disruption of “single stories” through children’s literature. Journal of Children’s Literature, 40(1), 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R., Deliman, A., & Robertson, M. K. (2023). Curriculum integration using picture books: Combining language arts and social studies standards to address controversial issues. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 36(1), 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, D. (2022). Scaffolding in-depth learning: Picturebooks for intercultural citizenship in primary English teacher education. In D. Valente, & D. Xerri (Eds.), Innovative practices in early english language education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, V. M. (2017). Critical literacy. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H., & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M. (2019). What is student agency and why is it needed now more than ever? Theory into Practice, 59, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M. (2021). Student agency in the classroom: Honoring student voice in the curriculum. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, B. (1988). Research currents: Does classroom drama affect the arts of language? Language Arts, 65(1), 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., Lonigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., & Caulfield, M. (1988). Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Developmental Psychology, 24(4), 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69(3), 848–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, J., & Edmiston, B. (1998). Imagining to learn: Inquiry, ethics, and integration through drama. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- *Williams, K. L., & Mohammad, K. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Eerdmans Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlwend, K. (2022). Serious play for serious times. The Reading Teacher, 76(4), 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Woodson, J. (2012). Each kindness. Nancy Paulsen Books. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

| Introduction: What is Empathy? Stand in My Shoes (Sornson, 2013) |

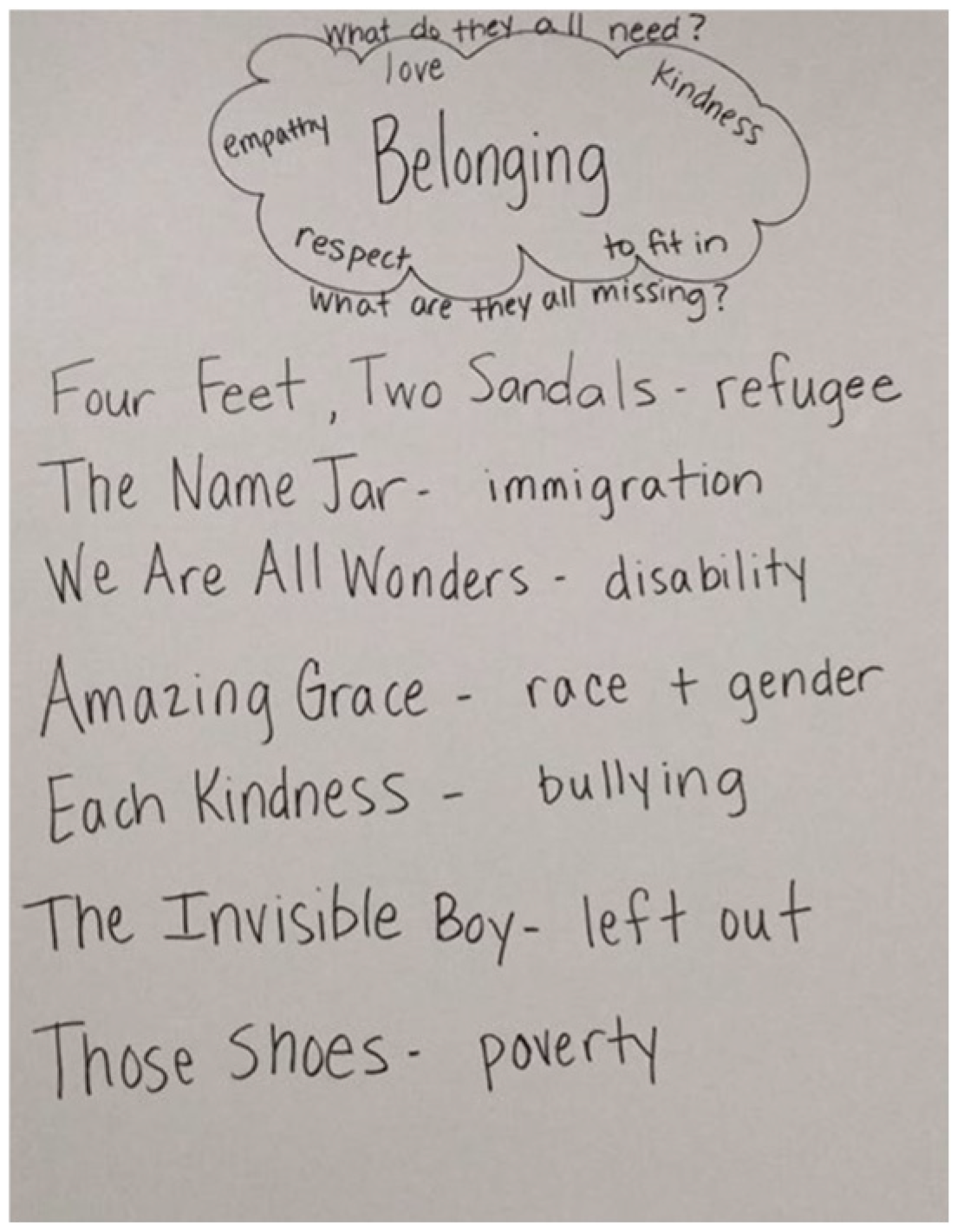

| Belonging |

| *Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story (Noble Maillard, 2019) *Where Are You From? (Saied Méndez, 2019) My Name Is Sangoel (Williams & Mohammad, 2009) |

| Bullying |

| The Invisible Boy (Ludwig, 2013) Each Kindness (Woodson, 2012) |

| Identity |

| Amazing Grace (Hoffman, 1991) *Alma and How She Got Her Name (Martinez-Neal, 2018) *The Proudest Blue: A Story of Hijab and Family (Muhammad, 2019) |

| Perspective-Taking |

| Last Stop on Market Street (de la Peña, 2015) Hey, Little Ant (Hoose & Hoose, 1999) Big Red Lollipop (Khan, 2010) *Drawn Together (Le, 2018) |

| Poverty |

| Those Shoes (Boelts & Jones, 2009) *On Our Street: Our First Talk About Poverty (Roberts, 2018) |

| Activism/Agency |

| The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a Young Civil Rights Activist (Levison, 2017) *We Are Water Protectors (Lindstrom, 2020) One Plastic Bag: Isatou Ceesay and the Recycling Women of the Gambia (Paul, 2015) |

| Drama Strategy and Description | Writing Activity and Description |

| Tableaux—Dramatic engagement where participants make still images with their bodies to represent a scene | Defining Key Terms—In this activity, the children were asked to define empathy; this occurred at the start of the data collection phase and during the closing interviews |

| Reader’s Theater—Dramatic engagement where the students orally read scripts (usually the reader takes on one specific role) | Persuasive Writing—In this activity the students were persuading the reader to believe the boy should or should not squish the ant as an ending to the story Hey, Little Ant (1999) |

| Process Drama—A form of dramatic inquiry where the teacher and students create imaginary worlds to work through events and to address challenges using improvisation and elaboration (O’Neill, 1995) | Partner Writing—In this activity the children wrote about the similarities and differences they had with a partner after discussing the story, Same, Same but Different (2011). This occurred on a writing template that was created so that the children could write their personal stories side-by-side on one piece of paper. |

| Character Role-play with Props—Dramatic engagement where those in role imagine what it is like to step into a character’s shoes | Writing in Role—In this activity the children were writing as if they were the main character in Red, A Crayon’s Story (2015) |

| Hotseating—Dramatic engagement where a person (playing in role) sits in the “hotseat” and is asked questions by others who can be in or out of role | Writing to Explain Understanding—In this activity the students write about a character who felt empathy in the story The Invisible Boy (2013) |

| Improvisation with Props—Unplanned dramatic engagement where those in role use props and improvise | Open Writing—This writing activity encouraged the children to make up their own stories that included empathy or to write about real-life experiences that include someone who felt empathy |

| Mantle of the Expert—This involves the creation of a fictional world where students assume the role of experts (Heathcote & Bolton, 1995) |

| Thematic Analysis Questions |

|

| Critical Analysis Questions |

|

| Interview Questions | Post-Interview Responses |

| What does empathy mean? How can having empathy help? | “Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes. Trying to think of others’ feelings. It is important to show empathy so that we can make the world a better place.”—Vanessa “It means how others would feel and standing in their shoes if they’re getting left out. Um, if everybody haves it, everybody would be nice to each other.”—Rick |

| What do you think is the most important thing that you’ve learned? | “Not to bully or uninclude people or leave someone out which is basically unincluding them.”—Vanessa “Um, standing in other people’s shoes. Um, it helps because, if somebody got left out if you standed in their shoes, you would see how it feels to be left out.”—Rick |

| What is something that you learned that might help you in the future? | “Um, helping people out if they need something. Understanding what they are feeling.”—Vanessa “Being nice to other people.”—Rick |

| Do you think we should learn about other people’s perspectives? If so, why? If not, why not? | “Um, yeah. So, they can feel how they’re feeling and know how they’re feeling so if they do something wrong they can fix that.”—Vanessa “Yeah, because it, um, it might not feel good if you leave people out.”—Rick |

| How could having empathy help you think about other cultures or other places? | “I could study about their language and help them about ours. They can understand our world or our part of the world.”—Vanessa “If there’s a person that needs help, you can help them.”—Rick |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deliman, A. From Picturebooks to Play: Dialogic Pedagogy for Cultivating Agency and Social Awareness in Young Learners. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060731

Deliman A. From Picturebooks to Play: Dialogic Pedagogy for Cultivating Agency and Social Awareness in Young Learners. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):731. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060731

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeliman, Amanda. 2025. "From Picturebooks to Play: Dialogic Pedagogy for Cultivating Agency and Social Awareness in Young Learners" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060731

APA StyleDeliman, A. (2025). From Picturebooks to Play: Dialogic Pedagogy for Cultivating Agency and Social Awareness in Young Learners. Education Sciences, 15(6), 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060731