Linking Education, Culture and Community: A Proposal for an Intercultural Educational Triad

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Context and Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Analysis Plan

3. Results

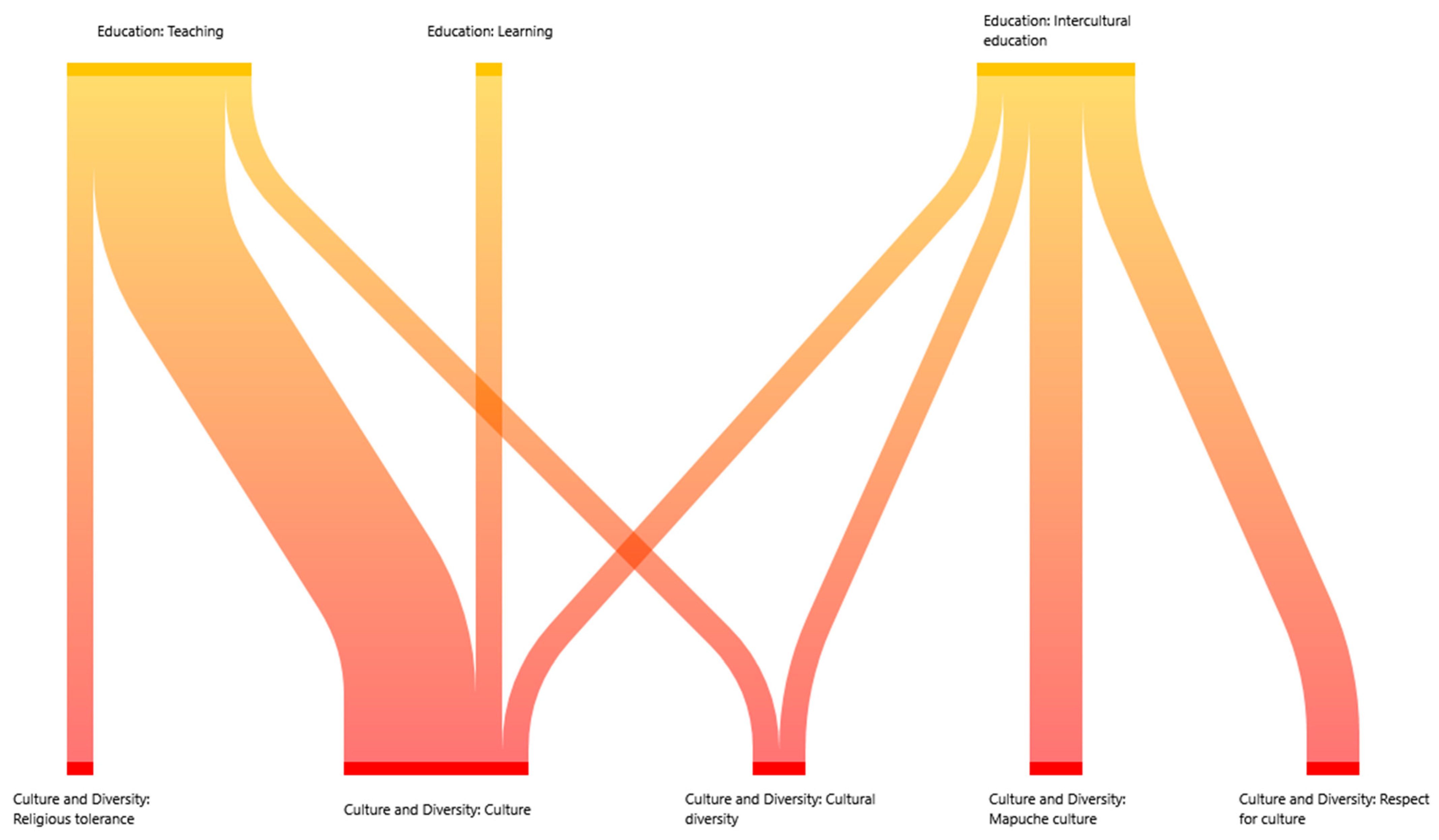

3.1. Culture and Diversity Category

For example, from the Mapuche point of view, the spiritual theme has a lot of influence, so being in a circle, being in contact with nature, for example, the circular methodology is used a lot, right, duality, and that is not seen much in the, in the traditional culture.(Interviewee 1, quote 25)

I think that ninety or one hundred percent of the children are of Mapuche ancestry, so I think that eighty percent were very participative.(Interviewee 3, quote 46)

We make some meals, we also participate with them, I feel that emotionally this is very good for the children and for us, to see us participate because they, apart from the fact that we teach them to our students, they also teach us about their culture.(Interviewee 2, quote 32)

Yes, I think that here you live more in community, everything is more like a meeting, much closer, in fact, here I experienced the first We tripantu (Mapuche New Year) with which I participated and for me it was like everything was new, first of all like the connection with the earth, sharing food, all of that was new to me, unlike in urban schools and besides that here there is a very familiar atmosphere and that allows for greater closeness.(Interviewee 3, quote 91)

3.2. Education Category

you can’t ask a child who feels anger to learn to multiply, you can’t, because there is something neural that prevents him/her, now we talk about raising with respect, about teaching, because there are things that are blocked in the brain when we are angry, when we are sad.(Interviewee 12, quote 64)

I believe that in all spaces they can learn, I believe that in all spaces they can learn, it depends on how the teacher delivers the strategies, varies the work dynamics, I believe that it depends on the teacher.(Interviewee 3, quote 87)

as a teacher, even if we don’t want to, we always have to know what the context is that the students have, especially at the moment of learning, so it is both physical, and also what one feels as part of oneself.(Interviewee 8, quote 10)

That is to say, the teaching is adapted, there are also curricular educations that we call it that for example ‘hey, remember’, that is, later we had our code, it was like ‘in the test you are not going to put a tremendous indication’ if the child with luck, no, he will not be able to read it, if it was four basic and the child was just learning the letters.(Interviewee 15, quote 37)

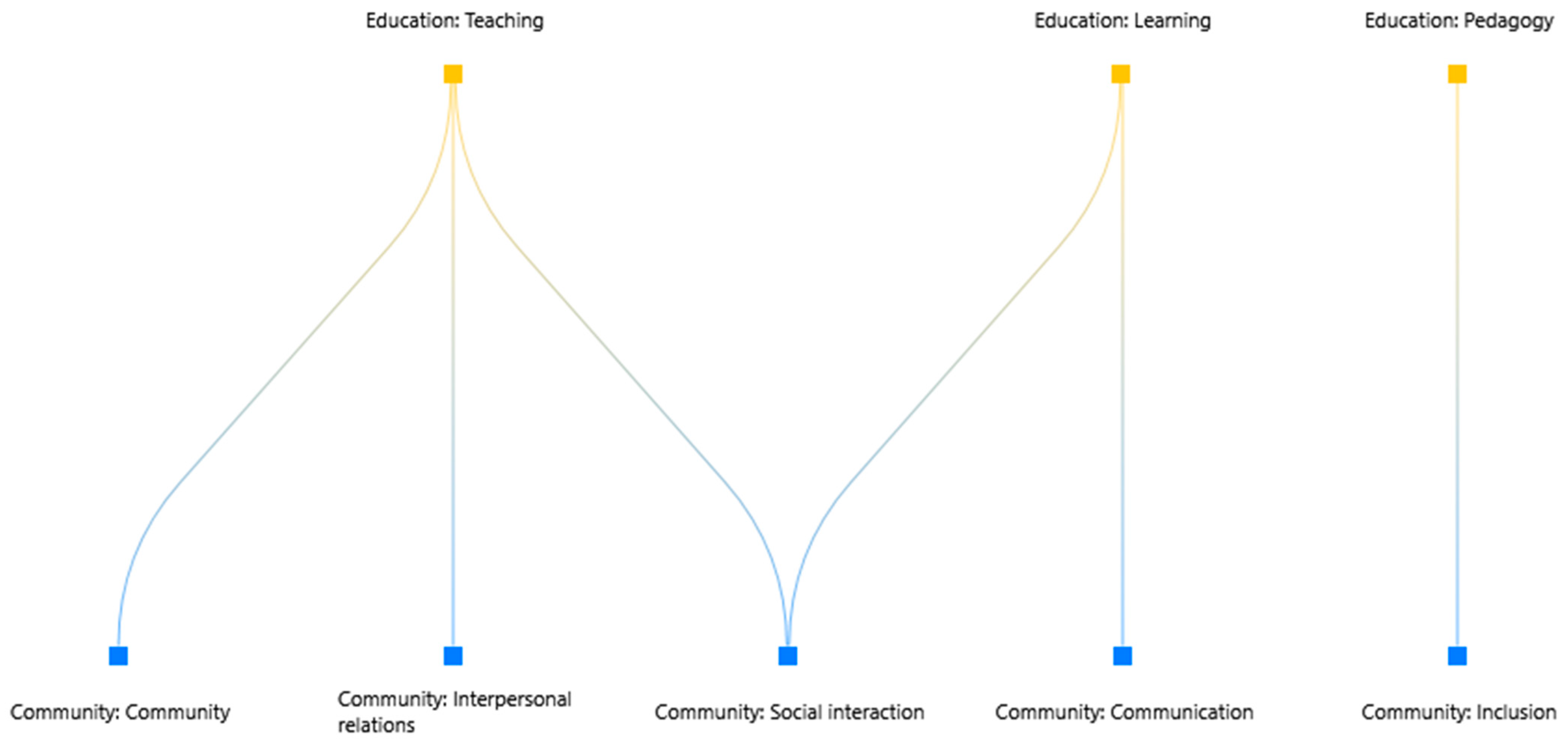

3.3. Community Category

Socially, there is a very good communication between the communities because we participate with communities, you have to think that there are people there who are in charge of the communities who are the Loncos, so they are like the heads of the communities and we have to have a good communication or socially adapt to all that, is to adapt to all the students as well, The director has to go and visit the Lonco and the whole thing so that there is good communication as well, so socially one adapts to all these types of communities that exist, so it is, sometimes it is a bit complicated, but we all try to adapt.(Interviewee 2, quote 29)

Look, I don’t remember in what year, they started to put the names in Mapu-Zungun and Spanish on the parts of the school, so, for example, the dining room, the library, they put a little piece of paper outside that space, or the playground, the bathroom, like those words. I could say that they tried to consider the culture, but from what I saw I couldn’t say that the school doesn’t do it.(Interviewee 5, quote 43)

I think that this loss of knowledge is because of what the children experience, they are no longer educated by their grandparents or they have little relationship with their grandparents who are the transmitters of cultural content, we could say, so they adopt a non-Mapuche lifestyle, many no longer live in the countryside(Interviewee 1, quote 27)

They have lost a bit, they have lost a bit, before they used to do much more, even with animals, they used to kill animals in the school, they used to do rogations (ceremonies where ancestral ceremonies are performed to thank the forces of nature and ask for the health, abundance and well-being of the community), the Machi used to go there and then there was a drastic change and then they didn’t do rogations anymore, they just did an act and that was like a lack of respect for the community and there was also a lot of tension, a lot of tension with the community and several supporters withdrew their children from school because of the same thing.(Interviewee 3, quote 112)

3.4. Co-Occurrence Analysis Between Categories

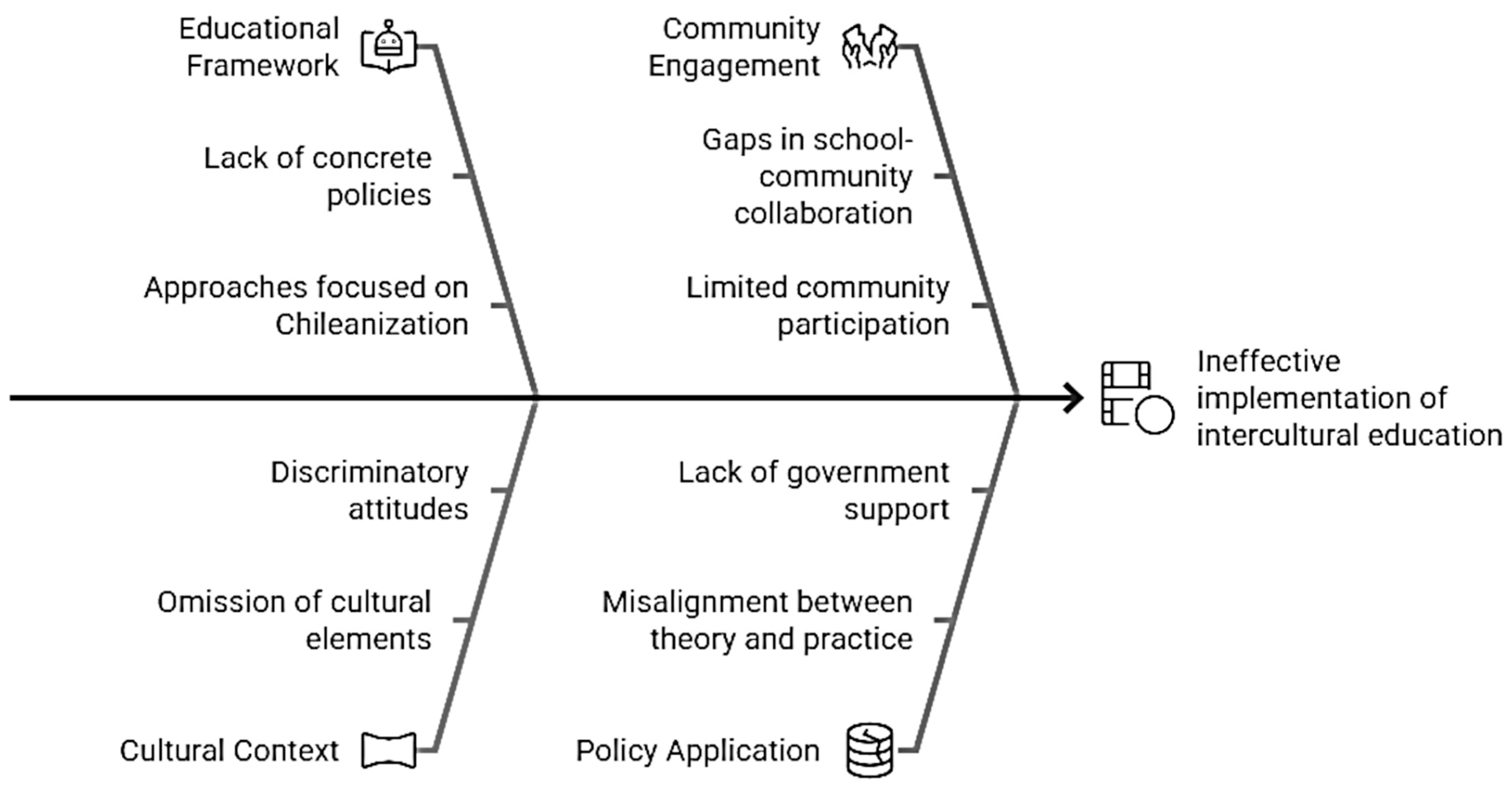

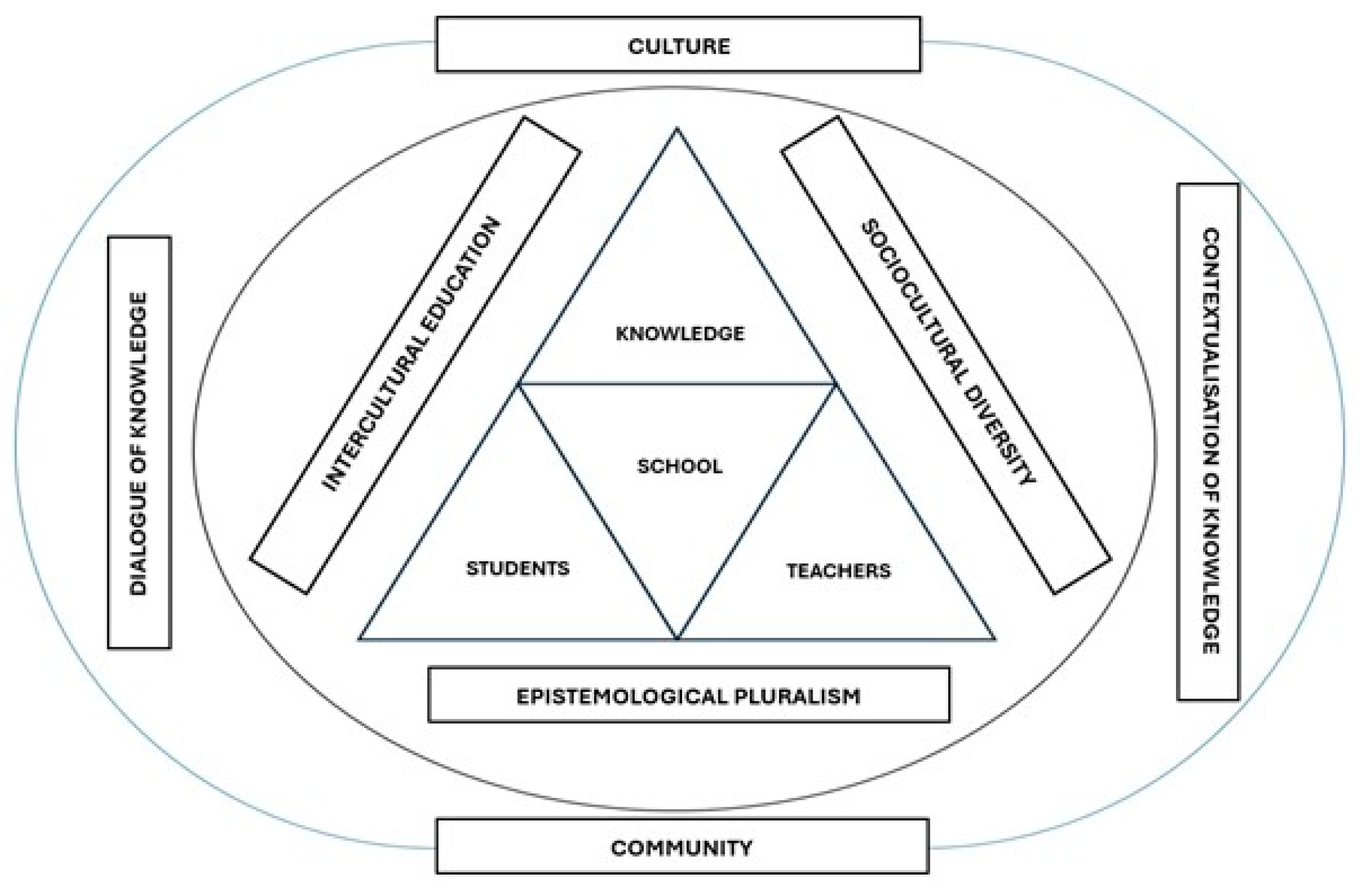

4. Discussion

4.1. Proposal for Intercultural Educational Articulation

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Umairi, M. (2023). Development of social interaction and behavior for early childhood education in the era society (5.0). JOYCED: Journal of Early Childhood Education, 3(2), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio Gervás, J. M., Tilley Bilbao, C. D., & Orozco Gómez, M. L. (2015). La escuela como mecanismo de aculturación en la Araucanía durante el siglo XIX. Revista Colombiana de Educación, (68), 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ortega, K. (2022). Voces de educadores tradicionales mapuches sobre la educación intercultural en la Araucanía, Chile. Diálogo Andino, (67), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ortega, K., Muñoz, G., & Quintriqueo, S. (2023). Discriminación percibida entre profesor y educador tradicional en la educación intercultural en La Araucanía, Chile. Educação e Pesquisa, 49, e250586. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Ortega, K., & Quintriqueo-Millán, S. (2020). Ensino superior no contexto mapuche: O caso de La Araucanía, Chile. Revista Electrónica Educare, 24(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, G., & Toro-Mayorga, L. I. (2021). Interacción social entre los niños y niñas con necesidades educativas especiales y sus pares. Una revisión narrativa. Revista Ecos de la Academia, 7(13), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gallego, M. M., Herrera-Rivera, O., & Guzmán-Atehortúa, N. (2021). Estrategias de acompañamiento educativo y familiar en la educación inicial: Una revisión teórica. Revista Lasallista de Investigación, 18(2), 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Véliz, J. C., Tereucán-Angulo, J. C., & Pérez-Morales, S. H. (2022). Prácticas dialógicas y colaborativas que promueven los kimeltuchefes para articular conocimientos y saberes mapuche y, escolares en contextos mapuche. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26(2), 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizama Colihuinca, K., Riquelme Mella, E., Fuentes Vilugrón, G., & Muñoz-Troncoso, F. (2023). Teaching of educational content expressing mapuche values to children in initial education in La Araucanía Region, Chile. Education Sciences, 13(7), 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-García, M. Á., & López-Suárez, A. D. (2016). Ejemplificación del proceso metodológico de la teoría fundamentada. Cinta de Moebio, (57), 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbor-Balón, C. M. (2024). Habilidades sociales y relaciones interpersonales en docentes como agentes educativos. Revista Arbitrada Interdisciplinaria Koinonía, 9(17), 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, A. R., Romero, J. J. V., & Posada, J. J. Z. (2021). Familia y escuela: Educación afectivo-sexual en las escuelas de familia. Revista virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, (63), 312–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, I., Riquelme-Mella, E., Saldivia, X., & Fuentes-Vilugrón, G. (2023). Education of the affective ideal un contexts of cultural diversity: BIBLIOMETRIC and thematic analysis (2006–2021). International Journal of Membrane Science and Technology, 10(2), 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro de Estudios MINEDUC. (2024). Análisis de la educación rural en Chile. Available online: https://centroestudios.mineduc.cl/2024/03/05/evidencias-61-analisis-de-la-educacion-rural-en-chile/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Choez, J. S. M., Bazurto, D. C. P., & Zambrano, D. P. C. (2022). Los tipos de familia y su incidencia en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes de educación básica. REFCalE: Revista Electrónica Formación y Calidad Educativa, 91–106. Available online: https://refcale.uleam.edu.ec/index.php/refcale/article/view/3523 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Cornejo, C. O., Rubilar, F. C., Díaz, M. C., & Rubilar, J. C. (2014). Cultura y liderazgo escolar: Factores claves para el desarrollo de la inclusión educativa. Revista Electrónica “Actualidades Investigativas en Educación”, 14(3), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, H. T., & Carrillo, M. F. (2020). Elementos críticos de la escuela en territorio mapuche. Educar em Revista, 36, e66108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Espriella, R., & Restrepo, C. G. (2020). Teoría fundamentada. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 49(2), 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domich, M. A., & Lalangui, J. A. M. (2022). Diversidad cultural y educación: Una mirada desde la etnia Saraguro–Ecuador. Revista Dialogus, (10), 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Vilugrón, G., Arriagada-Hernández, C., Caamaño-Navarrete, F., Vera Gajardo, N., & Riquelme Mella, E. (2025a). Social representations about the concepts of emotion and culture according to student teachers. Pakistan Journal of Life & Social Sciences, 23(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Vilugrón, G., Caamaño-Navarrete, F., Riquelme-Mella, E., Godoy Rojas, I., Saavedra-Vallejos, E., del Val Martín, P., Muñoz-Troncoso, F., & Arriagada-Hernández, C. (2025b). The impact of physical/natural spaces on the mental and emotional well-being of students according to the report of rural female teachers. Psychiatry International, 6(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Vilugrón, G., Saavedra Vallejos, E., Rojas Mora, J., & Riquelme Mella, E. (2023). Incidencia de los espacios escolares sobre la regulación emocional y el aprendizaje en contextos de diversidad social y cultural. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 22(49), 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, A. J. L., Maza, A. M. C., López, M. F. G., Bermúdez, P. A. S., & Chicaiza, R. M. P. (2025). Como influye la pedagogía dentro del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 9(1), 3124–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, B. M., & Niemelä, R. (2010). Formas de implicación de las familias y de la comunidad hacia el éxito educativo. Revista Educación y Pedagogía, (56), 69–77. Available online: https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/revistaeyp/article/view/9821 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Henríquez, S. S., Moltó, M. C. C., Fernández, V. H., Adell, M. J. B., & Carrillo, M. F. (2021). Sensibilidad intercultural en el alumnado y su relación con la actitud y estilo docente del profesorado ante la diversidad cultural. Interciencia, 46(6), 256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, T. (2007). Cultura, diversidad y desarrollo humano. Quórum. Revista de Pensamiento Iberoamericano, (17), 59–63. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/520/52001707.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Herrera Rodríguez, J. I., Guevara Fernández, G. E., & Munster de la Rosa, H. (2015). Los diseños y estrategias para los estudios cualitativos. Un acercamiento teórico-metodológico. Gaceta Médica Espirituana, 17(2), 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Sáiz, M. S., González-Elorza, A., & Gómez, G. R. (2023). Aportaciones metodológicas para el uso de la entrevista semiestructurada en la investigación educativa a partir de un estudio de caso múltiple. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 41(2), 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]. (2018). Radiografía de género: Pueblos originarios en Chile 2017. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/genero/documentos-de-análisis/documentos/radiografia-de-genero-pueblos-originarios-chile2017.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Jean, H. (1988). Le triangle pédagogique. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Naranjo, Y., & Sánchez-Antonio, J. C. (2020). Pluralismo epistémico, alteridad, comunidad y escuela: Una relación que discutir. De Prácticas y Discursos, 9(13), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriakina, A. A., Tretyakova, T. V., Ignatiev, V. P., & Olesova, S. G. (2019). Formation of tolerance in multicultural educational environment. Revista Espacios, 40(09), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla Sepúlveda, J. (2020). República colonial chilena 1929–1973. Escuela e invisibilización del mapun-kimun del pueblo nación mapuche. Revista historia de la Educación Latinoamericana, 22(35), 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Maldonado, P., Armengol Asparó, C., & Muñoz Moreno, J. L. (2019). Interacciones en el aula desde prácticas pedagógicas efectivas. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 18(36), 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Saavedra, S., Quintriqueo Millán, S., Arias-Ortega, K., & Zapata Zapata, V. (2022). Vinculación familia-escuela-comunidad: Una necesidad para la educación intercultural en infancia. CUHSO (Temuco), 32(1), 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica-Johnson, F. (2024). Alteridad y diversidad en la educación Latinoamericana. Aportes epistemo-lógicos de Paulo Freire. Revista de Inclusión Educativa y Diversidad (RIED), 2(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, G., Quintriqueo, S., Torres, H., & Galaz, A. (2022). Küpan y tuwün como fondos de conocimiento para contextualizar la educación intercultural en territorio mapuche. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 11(1), 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Troncoso, G. (2021). Educación familiar e intercultural en contexto mapuche: Hacia una articulación educativa en perspectiva decolonial. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia), 47(1), 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, G. R., Zambrano, V. V., & Sepúlveda, J. G. M. (2024). Percepción de directivos escolares hacia la escolarización alumnos inmigran-tes en una escuela de enseñanza básica de La Araucanía. Revista de Inclusión Educativa y Diversidad (RIED), 2(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzún, J. d. D., Parcerisa, L., & Carrasco, A. (2022). Discriminación étnica y cultural en procesos de elección de escuela en minorías socioculturales en Chile. Psicoperspectivas, 21(1), 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pailthorpe, B. C. (2017). Emergent design. In The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1–2). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Rodríguez, O. A. (2021). La teoría fundamentada: Origen, supuestos y perspectivas. Intersticios Sociales, (22), 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek de Pinto, E., Ávila de Vanegas, N., & Matos de Rojas, Y. (2015). Concepciones sobre participación social que poseen los actores educativos y sus implicaciones. Paradigma, 36(2), 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pire, A., & Rojas, A. (2020). Escuela y familia: Responsabilidad compartida en el proceso educativo. Conrado, 16(74), 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada-Carrasco, P. (2022). Educación intercultural: Una alternativa a la educación monocultural en contexto Mapuche. CUHSO (Temuco), 32(2), 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilaqueo, D., Riquelme, E., Paez, D., & Mera-Lemp, M. J. (2023). Dual educational rationality and acculturation in Mapuche people in Chile. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quivy, R., & Carnpenhoudt, L. V. (2005). Manual de investigación en ciencias sociales. Limusa. Available online: https://www.fapyd.unr.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/manual-de-investigacion-en-ciencias-sociales-quivy-campenhoudt.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ramírez, P. M., Ruiz, A. F., Mayorga, D. M., & Chida, J. C. (2024). Habilidades sociales como clave en el éxito académico. 593 Digital Publisher CEIT, 9(1), 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Iñiguez, A. A. (2017). La educación con sentido comunitario: Reflexiones en torno a la formación del profesorado. Educación, 26(51), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, N. R., Alzate, J. I. C., Taborda, Y. M., & Ayala, L. J. (2023). Currículo contextualizado con pertinencia cultural para la educación infantil en contextos rurales. REICE: Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 21(3), 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, G. R. B. (2021). El aprendizaje significativo como estrategia didáctica para la enseñanza–aprendizaje. Polo del Conocimiento: Revista Científico-Profesional, 6(5), 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, R. D. (2015). Cultura: Factor determinante del desarrollo humano. Entorno, (58), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J., & Gómez, T. (2021). Aprendizaje contextualizado y expansivo: Una propuesta para dialogar con las incertidumbres en los procesos educativos. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 21(3), 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Salamanca, H. A. B., Cárdenas, P. A. R., Pérez, T. V., Diaz, N. F. G., Ortega, J. A. G., & Gámez, M. I. V. (2024). La entrevista semiestructurada: Una herramienta pertinente en la percepción de valores sociales para la vida. Revista Lasallista de Investigación, 21(1), 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín Ulloa, C., Rogers, P., Troncoso, C., & Rojas, R. (2020). Camino a la educación inclusiva: Barreras y facilitadores para las culturas, políticas y prácticas desde la voz docente. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 14(2), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, C., & Giné, C. (2016). Escuela, familia y comunidad: Construyendo alianzas para promover la inclusión. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 10(1), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefoni, C., & Stang, F. (2016). Educación e interculturalidad en Chile: Un marco para el análisis. Estudios Internacionales (Santiago), 48(185), 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suricalday, A. S., García-Varela, A. B., & Castro-Martín, B. (2022). Desarrollo de un modelo de investigación educativa basado en la teoría fundamentada constructivista. Márgenes Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 3(2), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, G. O. M., & Millán, S. Q. (2019). Escolarización socio-histórica en contexto mapuche: Implicancias educativas, sociales y culturales en perspectiva intercultural. Educação & Sociedade, 40, e0190756. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Valdés, I., Guerra Iglesias, S., & Camargo Ramos, M. (2020). Las habilidades de interacción social: Un puente hacia la inclusión. Mendive. Revista de Educación, 18(1), 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, B. J., Berrio, V. B., & Díaz, K. C. (2020). La transición escolar como reto en el proceso formativo de los niños y niñas. Infancias Imágenes, 19(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, T. V., & Sutton, L. H. (2021). La codificación y categorización en la teoría fundamentada, un método para el análisis de los datos cualitativos. Investigación en Educación Médica, 10(40), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilugrón, G. F., Mansilla, E. A., Carrasco, I. B., Hernández, R. L., & Mella, E. R. (2023). Analysis of school educational spaces: A challenge for spatial relevance in contexts of sociocultural diversity. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 25(1), 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermeyer-Jaramillo, M. A. (2024). Construcción discursiva de estudiantes mapuches en torno a la machi: Racismo, escolarización y evangelización. Educação e Pesquisa, 50, e261949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermeyer-Jaramillo, M., & Osses Bustingorry, S. (2021). Aprendizaje de las ciencias basado en la indagación y en la contextualización cultural. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 20(42), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, A. U., Salazar, D. A. R., & Álvarez, O. H. (2021). Apuntes sobre teoría fundamentada constructivista en educación. In Investigación para ampliar las fronteras (p. 173). Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, V. A. (2022). Relación familia-escuela en el contexto de diversidad social y cultural, desde un enfoque educativo intercultural: Principales tensiones epistemológicas. Revista Educación, 46(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Question |

|---|---|

| Experience and context | 1. Could you describe your experience as a teacher in rural contexts? |

| 2. What characteristics do you think are important in the socio-cultural context of your teaching practice? | |

| 3. How does this context influence the emotional needs of your students? | |

| Socio-cultural knowledge and emotions | 4. What local cultural knowledge or knowledge do you consider important for emotional regulation? |

| 5. What are some specific examples of how this knowledge is reflected in the community’s daily life? | |

| 6. How do educators integrate knowledge of emotional regulation into their pedagogical practices? | |

| Pedagogical practices and strategies | 7. What strategies do you use to promote emotional regulation in your teaching practices? |

| 8. How do you incorporate sociocultural knowledge into these strategies? | |

| 9. Have you noticed any positive effects on your students’ emotional regulation by incorporating this knowledge into your teaching practices? In what ways? | |

| Challenges and opportunities | 10. What are the main challenges you face when integrating socio-cultural knowledge into the teaching of emotional regulation? |

| 11. What resources or support do you consider necessary to strengthen this approach? | |

| 12. What opportunities do you see for integrating socio-cultural knowledge into rural education in the future? |

| Category | Codes | Percentage | Citations | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture and diversity | 22 | 44.9% | 295 | 53% |

| Education | 16 | 32.7% | 168 | 30.2% |

| Community | 11 | 22.4% | 94 | 16.9% |

| Total | 49 | 100% | 557 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes-Vilugrón, G.; Sandoval-Obando, E.; Landeros-Guzmán, D.; Pérez-Quinteros, L.E.; Arriagada-Hernández, C.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Etchegaray-Pezo, P.; del Val Martín, P.; Jara-Tomckowiack, L.; Muñoz-Troncoso, G.; et al. Linking Education, Culture and Community: A Proposal for an Intercultural Educational Triad. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060705

Fuentes-Vilugrón G, Sandoval-Obando E, Landeros-Guzmán D, Pérez-Quinteros LE, Arriagada-Hernández C, Caamaño-Navarrete F, Etchegaray-Pezo P, del Val Martín P, Jara-Tomckowiack L, Muñoz-Troncoso G, et al. Linking Education, Culture and Community: A Proposal for an Intercultural Educational Triad. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060705

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes-Vilugrón, Gerardo, Eduardo Sandoval-Obando, Daniella Landeros-Guzmán, Lorena Elizabeth Pérez-Quinteros, Carlos Arriagada-Hernández, Felipe Caamaño-Navarrete, Paulo Etchegaray-Pezo, Pablo del Val Martín, Lorena Jara-Tomckowiack, Gerardo Muñoz-Troncoso, and et al. 2025. "Linking Education, Culture and Community: A Proposal for an Intercultural Educational Triad" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060705

APA StyleFuentes-Vilugrón, G., Sandoval-Obando, E., Landeros-Guzmán, D., Pérez-Quinteros, L. E., Arriagada-Hernández, C., Caamaño-Navarrete, F., Etchegaray-Pezo, P., del Val Martín, P., Jara-Tomckowiack, L., Muñoz-Troncoso, G., & Muñoz-Troncoso, F. (2025). Linking Education, Culture and Community: A Proposal for an Intercultural Educational Triad. Education Sciences, 15(6), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060705