Exploring the Effectiveness of a Virtual Coaching Program to Support Staff Working at Families as First Teachers Playgroups in the Remote Northern Territory, Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

Families as First Teachers (FaFT) Playgroups

The Current Study

- How did the virtual coaching model impact participants’ levels of mastery and fidelity in the implementation of Conversational Reading strategies?

- How did participants engage with the virtual coaching model, and what were their perceptions of the model overall?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment

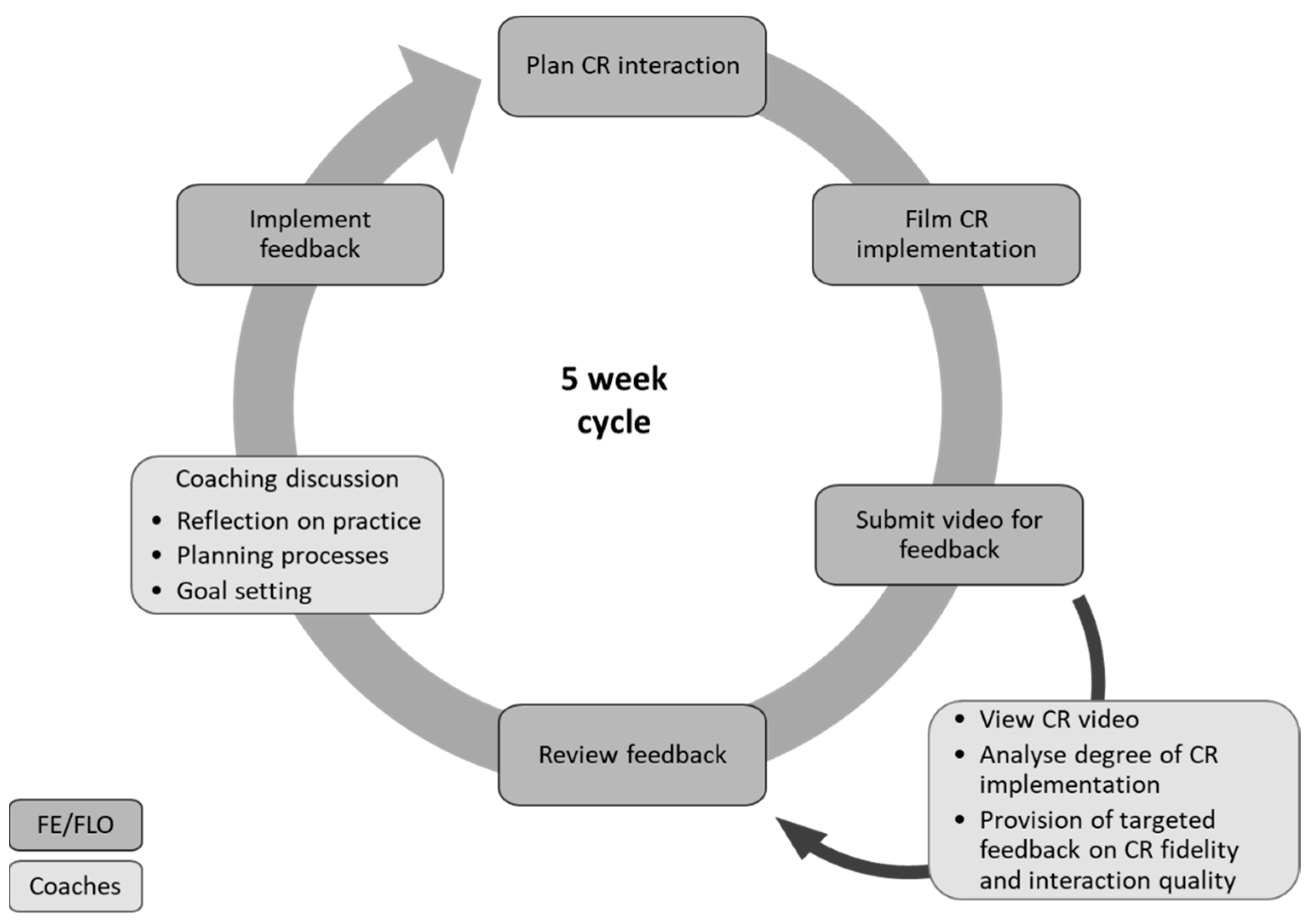

2.2. The Coaching Program

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Mastery and Fidelity of Implementation

2.3.2. Participant Engagement and Perceptions of the Program

3. Results

3.1. Participant Details

Content and Frequency of Coaching Feedback

3.2. Mastery of Implementation

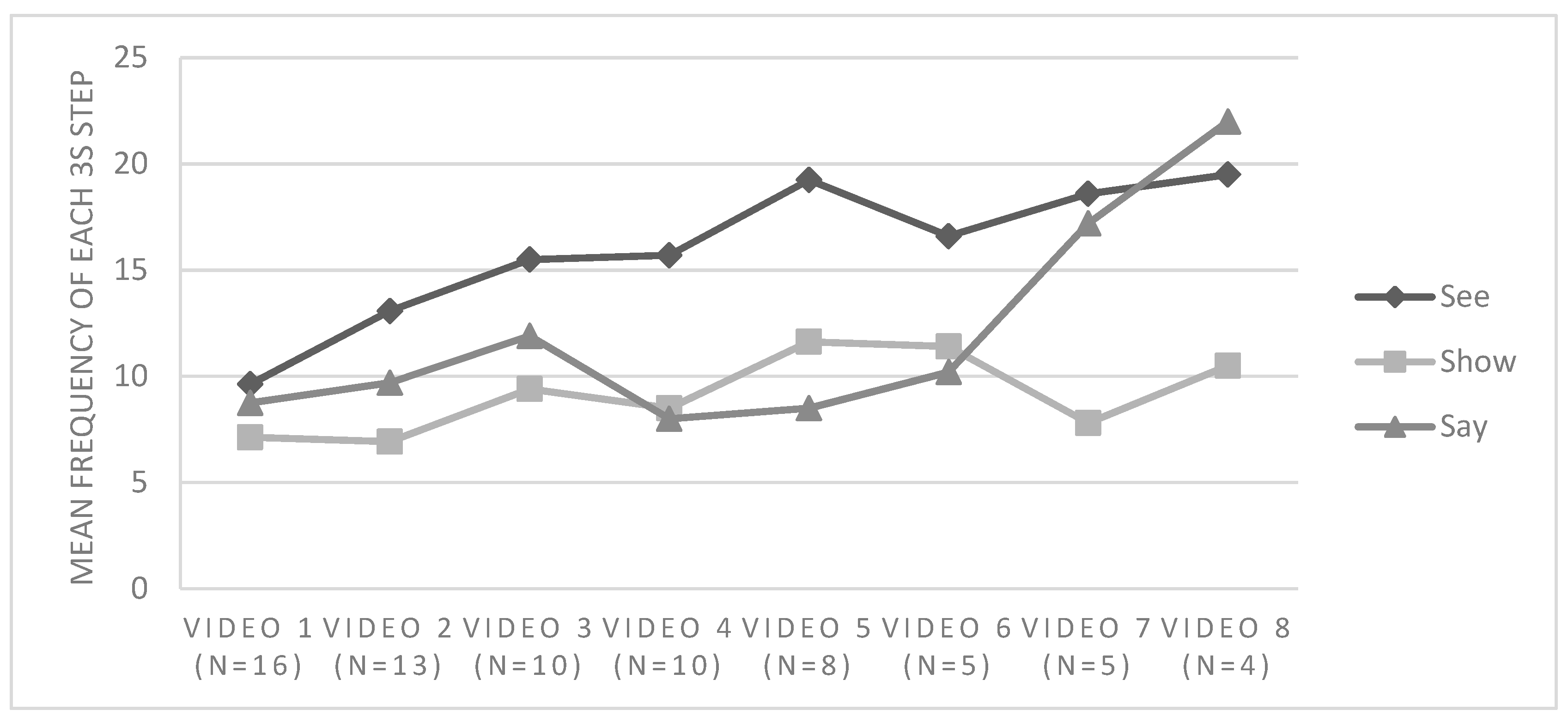

3.2.1. Frequency of 3S Implementation

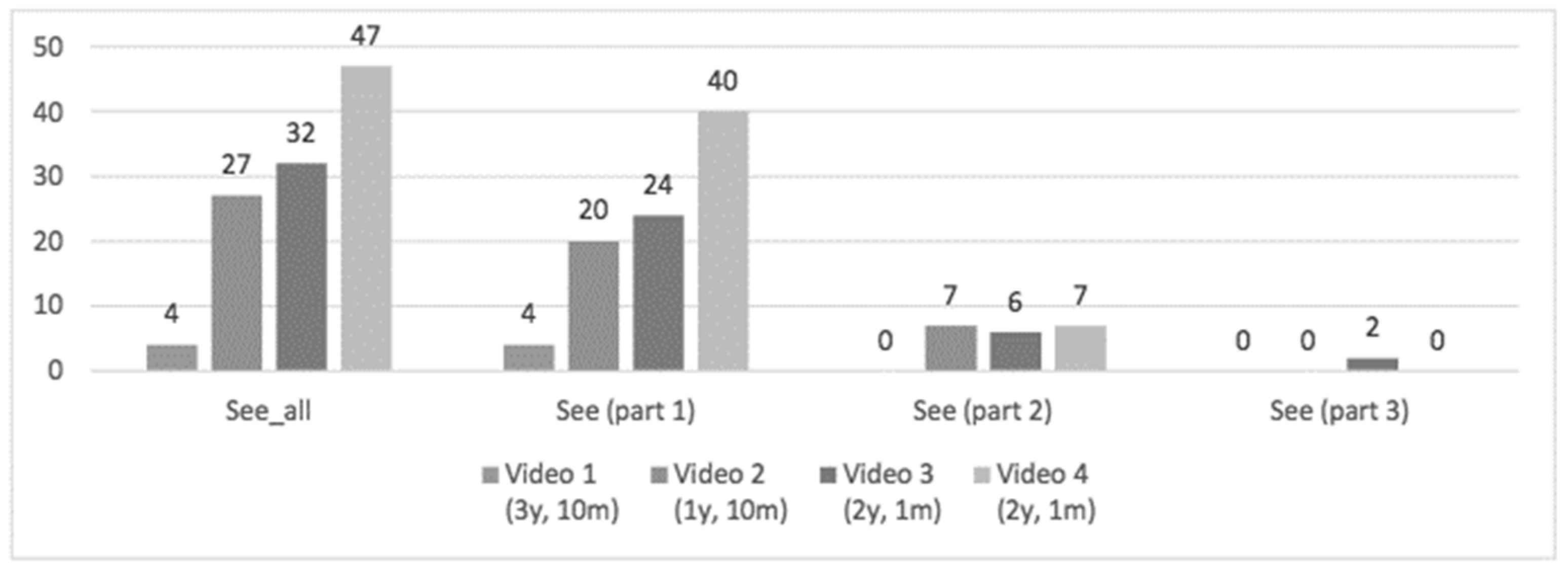

3.2.2. Use of 3S Steps in Combination

3.2.3. Exemplars

3.2.4. Exemplar 1, Jodie

3.2.5. Exemplar 2, Maggie

3.2.6. Exemplar 3, Sonia

3.3. Participant Perceptions of and Engagement with the Program

Participant Feedback

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arcos Holzinger, L., & Biddle, N. (2015). The relationship between early childhood education and care (ECEC) and the outcomes of indigenous children: Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC). Working paper No. 103/2015. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR). [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. (2020). Closing the gap report 2020. Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2017). Aboriginal and Torres strait islander health performance framework 2017 report: Northern territory. Cat. no. IHW 186. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Best Start Resource Centre. (2010). Founded in culture: Strategies to promote early learning among first nations children in Ontario. Best Start Resource Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman, S., Sayers, M., Goldfeld, S., & Kline, J. (2009). Population monitoring of language and cognitive development in Australia: The Australian early development index. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(5), 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, I., Cohrssen, C., Eadie, P., & Tayler, C. (2017). Seeing myself as others see me: Using video to support reflective practice in initial teacher education with a cross-country cohort. In Annual international conference on Education and e-Learning (EeL). Global Science and Technology Forum (GSTF). [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, I., & Tayler, C. (2016). Effects of an evidence-based intervention on the Australian English language development of a vulnerable group of young aboriginal children. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 41(4), 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M., Xue, Y., Auger, A., Tien, H.-C., Mashburn, A., Cavadel, E. W., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. (2016). Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Secondary data analyses of child outcomes: II. Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Methods. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(2), 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F., Wasik, B. H., Pungello, E., Burchinal, M., Barbarin, O., Kainz, K., Sparling, J. J., & Ramey, C. T. (2008). Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(4), 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2022). Australian early development census national report 2021. Department of Education, Skills and Employment. [Google Scholar]

- De Vincentiis, B., Guthridge, S., Spargo, J. C., Su, J.-Y., & Nandakumara, S. (2019). Story of our children and young people, northern territory 2019. Darwin. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, P., Page, J., & Murray, L. (2020). Continuous improvement in early childhood pedagogical practice: The Victorian advancing early learning (VAEL) study. In S. Garvis, & H. Lenz Taguchi (Eds.), Quality improvement in early childhood: Working to enhance children’s learning outcomes. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Ponder, B. B., & Pan, Y. (2017). Improving teacher-child interactions: A randomized control trial of making the most of classroom interactions and my teaching partner professional development models. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elek, C., Gubhaju, L., Lloyd-Johnsen, C., Eades, S., & Goldfeld, S. (2020). Can early childhood education programs support positive outcomes for indigenous children? A systematic review of the international literature. Educational Research Review, 31, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapany, D., Murukun, M., Goveas, J., Dhurrkay, J., Burarrwanga, V., & Page, J. (2021). Empowering aboriginal families as their children’s first teachers of cultural knowledge, languages and Identity at Galiwin’ku FaFT playgroup. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 47(1), 183693912110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S., Connor, E. O., Connor, M. O., Sayers, M., Moore, T., Kvalsvig, A., & Brinkman, S. (2016). The role of preschool in promoting children’s healthy development: Evidence from an Australian population cohort. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 35, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, J., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., Vass, G., & Moodie, N. (2019). Factors contributing to educational outcomes for First Nations students from remote communities: A systematic review. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthridge, S., Li, L., Silburn, S., Li, S. Q., McKenzie, J., & Lynch, J. (2016). Early influences on developmental outcomes among children, at age 5, in Australia’s northern territory. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 35, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B., Hatfield, B., Pianta, R., & Jamil, F. (2014). Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher–child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Development, 85(3), 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janus, M., & Offord, D. (2007). Development and psychometric properties of the early development Instr ment (EDI): A measure of children’s school readiness. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 39(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellard, K., & Paddon, H. (2016). Indigenous participation in early childhood education and care—Qualitative case studies. Australian Government, The Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakouer, J. (2016). Aboriginal early childhood education: Why attendance and true engagement are equally important. Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). [Google Scholar]

- Landry, S. H., Swank, P. R., Smith, K. E., Assel, M. A., & Gunnewig, S. B. (2006). Enhancing early literacy skills for preschool children: Bringing a professional development model to scale. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(4), 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Paro, K. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Classroom assessment scoring system. The Elementary School Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Leske, R., Sarmardin, D., Woods, A., & Thorpe, K. (2015). What works and why? Early childhood professionals’ perspectives on effective early childhood education and care services for indigenous families. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 40(1), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashburn, A. J., Downer, J. T., Hamre, B. K., Justice, L. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2010). Consultation for teachers and children’s language and literacy development during pre-kindergarten. Applied Developmental Science, 14(4), 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., Tawell, A., Slot, P., Broekhuizen, M., & Leseman, P. (2015). Review of research on impact of ECEC CARE: A review of research on the effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) upon child development. Bodleian Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Moodie, N., Maxwell, J., & Rudolph, S. (2019). The impact of racism on the schooling experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: A systematic review. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M., Gray, S., Tarasuik, J., O’Connor, E., Kvalsvig, A., Incledon, E., & Goldfeld, S. (2016). Preschool attendance trends in Australia: Evidence from two sequential population cohorts. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 35, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2017). Promising practices in supporting success for indigenous students. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Page, J., Cock, M. L., Murray, L., Eadie, P., Niklas, F., Scull, J., & Sparling, J. (2019). An abecedarian approach with aboriginal families and their young children in Australia: Playgroup participation and developmental outcomes. International Journal of Early Childhood, 51, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, J., Murray, L., Niklas, F., Eadie, P., Cock, M. L., Scull, J., & Sparling, J. (2021). Parent mastery of conversational reading at playgroup in two remote northern territory communities. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, B., Tondeur, J., Pareja Roblin, N., Vanslambrouck, S., & Zhu, C. (2019). Improving teacher professional development for online and blended learning: A systematic meta-aggregative review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67, 1145–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R., Funk, G., Hamre, B., Stuhlman, M., Hadden, D. S., Downer, J., & Hall, A. (2007). My teaching partner consultancy manual [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Virginia.

- Pianta, R., Hamre, B., Downer, J., Burchinal, M., Williford, A., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Howes, C., La Paro, K., & Scott-Little, C. (2017). Early childhood professional development: Coaching and coursework effects on indicators of children’s school readiness. Early Education and Development, 28(8), 956–975. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C., Lipscomb, D., & Ruzek, E. (2021). Coaching teachers to improve students’ school readiness skills: Indirect effects of teacher–student interaction. Child Development, 92(6), 2509–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D. R., Diamond, K. E., Burchinal, M., & Koehler, M. J. (2010). Effects of an early literacy professional development intervention on head start teachers and children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, C. T., & Ramey, S. L. (2005). Early learning and school readiness: Can early intervention make a difference? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(4), 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, C. T., Sparling, J., & Ramey, S. L. (2012). Abecedarian: The ideas, the approach, and the findings. Sociometrics Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC). (2012). Improved outcomes for aboriginal and Torres strait islander children and families in early childhood education and care services: Learning from good practice. SNAICC. [Google Scholar]

- Slot, P. L., Leseman, P. P., Verhagen, J., & Mulder, H. (2015). Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in dutch early childhood education and care settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 33, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, E. K., Hindman, A. H., & Wasik, B. A. (2019). A review of research on technology-mediated language and literacy professional development models. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 40(3), 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgett, M., & Grace, R. (2011). Engaging with early childhood education and care services: The perspectives of Indigenous Australian mothers and their young children. Kulumun: Indigenous Online Journal, 1, 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wakerman, J., Humphreys, J., Russell, D., Guthridge, S., Bourke, L., Dunbar, T., Zhao, Y., Ramjan, M., Murakami-Gold, L., & Jones, M. P. (2019). Remote health workforce turnover and retention: What are the policy and practice priorities? Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasik, B. A., Bond, M. A., & Hindman, A. (2006). The effects of a language and literacy intervention on head start children and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Huang, R., Su, Y., Zhu, J., Hsieh, W. Y., & Li, H. (2022). Coaching early childhood teachers: A systematic review of its effects on teacher instruction and child development. Review of Education, 10(1), e3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 3S Step | Title 2 |

|---|---|

| See statement introducing descriptive language | “You are looking at a pink teddy bear.” |

| Show question prompting recall and understanding of colour concept | “Where is the thing that is pink?” |

| Say question to elicit three-word utterance from child | “Can you say ‘pink teddy bear’?” |

| Extracts from Planning Documents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary (Examples from Book) | See Statements | Actual See Statements Used in Interaction | |

| Video 3 | Home; Bed; Baby; Nana; Flowers; Swimming pool; Butterfly; Horse; Cat; Rabbit; Duck; Elephant; Tiger; Monkey; Crocodile | “Can you see the butterfly?” “You are looking at the horse” | “You are looking at the teddy bear” “It’s a rabbit” |

| Video 4 | Furry penguin; Bumpy strawberry; Sparkly moon; Shiny trunk; Soft butterfly; Fluffy cloud | “You can see a crocodile” “You’re looking at a fluffy penguin” | That’s a red strawberry” “That’s a bee. You are touching a black bee” “That’s a penguin. Fluffy penguin.” |

| Video 5 | As above (video 4) | “It’s a fluffy, white cloud” “Bumpy, red strawberry” “That’s a blue truck. A shiny, blue truck.” | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Page, J.; Brookes, I.; Elek, C.; Eadie, P.; Murray, L. Exploring the Effectiveness of a Virtual Coaching Program to Support Staff Working at Families as First Teachers Playgroups in the Remote Northern Territory, Australia. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060699

Page J, Brookes I, Elek C, Eadie P, Murray L. Exploring the Effectiveness of a Virtual Coaching Program to Support Staff Working at Families as First Teachers Playgroups in the Remote Northern Territory, Australia. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):699. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060699

Chicago/Turabian StylePage, Jane, Isabel Brookes, Catriona Elek, Patricia Eadie, and Lisa Murray. 2025. "Exploring the Effectiveness of a Virtual Coaching Program to Support Staff Working at Families as First Teachers Playgroups in the Remote Northern Territory, Australia" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060699

APA StylePage, J., Brookes, I., Elek, C., Eadie, P., & Murray, L. (2025). Exploring the Effectiveness of a Virtual Coaching Program to Support Staff Working at Families as First Teachers Playgroups in the Remote Northern Territory, Australia. Education Sciences, 15(6), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060699