Abstract

Current policy recommendations for initial teacher education encourage teaching code-related literacy (phonics, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness) over pedagogical knowledge, and engaging practice in learning to read. To enhance early childhood pre-service teacher (PST) practices, this mixed-methods pilot study investigated a tool to support PSTs studying birth-to-eight years teaching, pedagogical practice, and knowledge to teach code-related literacy and supplementary vocabulary in conjunction with quality children’s literature. The Non-Scripted Intentional Teaching (N-SIT) tool was developed and then trialled with early childhood PSTs (n = 24) in Queensland, Australia. The participants planned phonics learning experiences using the N-SIT and picture books (e.g., Pig the Pug; Snail and the Whale). Survey data gathered participants’ code-related literacy knowledge before and after the N-SIT training. The data revealed most PSTs felt well-to-somewhat prepared to teach beginning reading and vocabulary and less-to-somewhat prepared to teach phonics. The data further revealed that all participants could define phonics but reported mixed conceptual understandings of phonological and phonemic awareness. The PSTs’ knowledge of phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, and planning for phonics-focused teaching through children’s literature improved post-N-SIT activity. Planned direct systematic phonics instruction strategies through the intentional shared reading of children’s literature and the potential benefits of the N-SIT tool in early childhood initial teacher education are discussed.

1. Introduction

Government policy in Australia, the UK, and several states in the USA prioritise the teaching of phonics in the first years of formal schooling with children aged five years and above (elementary or primary school) (Department for Education, 2024a; Queensland Government, 2025). In Australia, three states mandate synthetic phonics to teach early reading to children in the Preparatory year (first year of school) (Queensland Government, 2024; Allan, 2024; New South Wales Government, 2023). Following the New South Wales and South Australian states, the Victorian State Government Minister for Education has also mandated phonics as an approach to teaching reading, specifically synthetic phonics instruction, to commence across all first years of school in 2025 (Carroll, 2024). Changes to explicit synthetic phonics teaching in schools in Australia, the UK, and the USA have impacted initial teacher education. In Australia, this has resulted in an increased focus on early reading and phonics instruction (Department of Education, 2023).

Teaching phonics is mandated in Australian schools; however, this is not the case for prior-to-school settings. There are diverse approaches to teaching phonics and early alphabet literacy in the prior-to-school years. For example, in Australia, the prior-to-school Early Years Learning Framework V2.0 (EYLF) (Department of Education, 2022) suggests that phonics instruction is introduced through exploration and teachers drawing attention to letters during shared reading and environmental print. Despite this, there are no requirements to know all of the letters of the alphabet and some sounds, whereas, in the UK, the Early Years Foundation Stage Statutory Framework (Department for Education, 2024b) for children from birth to five years expects children to know and say the main sound for each letter in the alphabet, 10 digraphs, and use sound blending. Moreover, there is wide variability in what is thought to be taught in pre-service early childhood (birth-to-five and birth-to-eight) teacher education programs (Weadman et al., 2021).

There are some sequential alignments made between the prior-to-school EYLF V2.0 (Department of Education, 2022), such as the EYLF Learning Outcome 5, Children are effective communicators, 5.2 Children engage with a range of texts and gain meaning from these texts, evident when children “sing and change rhymes, jingles and songs” (ACECQA, 2023, p. 60), and the school-based Australian Curriculum: English V9 Foundation Year (5–6 year old children) Content Descriptor AC9EFLE04, “explore and replicate the rhymes of sound patterns of literary texts, such as poems, rhymes and songs” (ACECQA, 2023, p. 57). The connections between the two documents aim to provide a vision for teaching and school transitions (Early Childhood Australia [ECA] & Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2014). However, a seamless connection is not always clear, particularly with phonics. The challenge for early childhood teachers and pre-service teachers (PSTS) studying to teach children in the prior-to-school years with children aged from birth-to-five years is understanding how to support the code-related literacy transition from preschool to school. In the UK, PSTs studying to teach children aged three- to eight-years-old are required to demonstrate an understanding of effective early reading instruction, including synthetic phonics, to graduate (Hendry, 2019). The recent Australian teacher education report further highlighted the need for PST expertise in early reading, including phonics (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023). Alphabetic literacy in the prior-to-school years with children aged two- to five-years-old is supported through play-based emergent literacy pedagogies. In contrast, many schools (primary/elementary) in English-speaking countries mandate an explicit, systematic, synthetic approach to phonics with children aged five to eight years. Early childhood teachers are now required to understand the range of literacy pedagogies and practices to provide continuity of code-related literacy across the year before school and the first year of school (Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority, 2024). However, an Australian study revealed that there is less emphasis on code-related literacy, particularly phonological awareness, in early childhood PST programs (Weadman et al., 2021)

Children in the prior-to-school years develop an emerging awareness of phonics knowledge, with alphabet knowledge learning occurring through shared picture book reading, letter games, and environment print (McLachlan & Arrow, 2011; Neumann et al., 2011, 2013; Roskos & Christie, 2011). The frameworks for teaching early literacy in prior-to-school contexts, e.g., the Australian Early Years Learning Frameworks (EYLF), Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF), and Queensland Kindergarten Learning Guidelines (QLKG), support children in learning to represent and identify some letters and sounds through explicit modelling, environmental print, and reading stories, in addition to experimenting with writing letters and sounds (Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority, 2024).

A recent Australian study by Campbell (2021) investigated early childhood teachers’ shared reading and literacy environments and employed the Early Language and Literacy Classroom Observation Scale Pre-K (Smith et al., 2008), as it relates to picture books and phonics instruction for children aged three-to-five years, and it revealed little evidence of the quality shared reading of picture books and phonics teaching. The researcher found that aesthetically inviting literacy learning areas were also not considered a priority (Campbell, 2021). These findings highlighted the need for early childhood teachers to know the effective outcomes of the well-planned use of shared reading and aesthetic book corners to support young children’s developing phonics knowledge in the prior-to-school years (Guo et al., 2012), as well as for early childhood PSTs to plan for high-quality literacy experiences through the use of children’s literature.

A USA study investigating print-referencing in shared reading with emergent readers also reported that early childhood teachers often dedicated more time to the literal features of picture books, such as labelling nouns (57%), and far less time on code-related talk (11%). Although less time was dedicated to code-related talk, the most commonly observed talk was around letters and sounds, and less so around oral language skills (e.g., vocabulary) (Zucker et al., 2013). Unless teachers are effectively trained, they are unlikely to incorporate print and phonological references that improve children’s code-related literacy, as EC teachers may feel that drawing attention to letters and sounds during reading will detract from the story (Zucker et al., 2013), or they may not fully understand how effective children’s shared reading of quality literature can be used to support developing reading for pleasure (Boardman, 2024).

Recent research suggests that many early childhood teachers may not have the requisite knowledge of how to teach code-related literacy (Campbell, 2020). To address this gap, the present study aimed to address contemporary early childhood PSTs’ literacy knowledge and literacy learning challenges by actively engaging and motivating them to develop an understanding of code-related literacy (phonics, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness), together with supporting vocabulary development to enhance children’s comprehension skills. Therefore, the Non-Scripted Intentional Teaching (N-SIT) Tool (a reflective pedagogical tool to support EC teachers in planning for teaching code-related literacy and building children’s vocabulary) was developed and trialled in the present study with first-year and third-year EC PSTs (n = 24) studying for their teaching degree with children aged from birth to eight years of age. The N-SIT tool served as a blueprint and reflective tool for more efficient planning for teaching phonics, phonological and phonemic awareness, and building vocabulary through engaging in shared reading of quality children’s picture books.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pre-Service Teachers’ Knowledge of Early Reading

PSTs’ preparedness level to teach early literacy has been a focus of research, policies, and media discussions over the past decade, particularly around recent standardised tests reporting the decline in Australian, UK, and USA literacy standards (Bostock & Boon, 2012; Duffy, 2023; Meeks et al., 2020; Meeks & Kemp, 2017; Tortorelli et al., 2021). The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) was assigned to tertiary teacher preparation institutions to ensure PSTs in Australia were provided with the skills and knowledge to provide effective phonics instruction. In the UK, a study initiated by the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted, 2012) found inconsistent teaching of early reading in ITE programs, requiring all new teachers, including the Early Years Foundation Stage (birth-to-five), to be well-trained to teach literacy, including phonics. Similarly, in the USA, there are few standards or curricular specifications on teaching early reading, often with teaching decisions being dependent on individual academics or universities, leading to increased discussions around developing a core curriculum for teaching early reading (Moats, 2025, 2020b).

Early childhood teachers’ literacy knowledge, including content knowledge, such as how oral and written language are mapped to each other, supports young children’s early literacy and language development (Piasta et al., 2020a). Some studies have identified that PSTs may not have the requisite knowledge of effective literacy instruction, including reading and writing (Bostock & Boon, 2012; Meeks et al., 2020; Tortorelli et al., 2021), and professional development may help to support early childhood teachers’ literacy knowledge and quality teaching practices (Ottley et al., 2015; Piasta et al., 2020b). An Australian study of final-year early childhood and primary education students across sixteen universities found that less than 60% believed phonics was important, with 37% selecting direct instruction as supporting research-based literacy practices (Meeks et al., 2020). Meeks et al. (2020) further add that limited phonics and decoding knowledge may indicate that PSTs are not learning about early reading processes in their pre-service education programs and may not have the requisite literacy knowledge for quality classroom practices. Further, a comprehensive literature review by Tortorelli et al. (2021) in the USA found that PSTs have difficulty identifying, segmenting, and blending phonemes, an essential component of alphabetic literacy. Moreover, PSTs could benefit from specific support around code-related literacy, including stronger connections between coursework and enacting practices (Tortorelli et al., 2021).

Recent studies of 437 early childhood graduate teachers in the USA by Piasta et al. (2020a) and Piasta et al. (2020b) also reported a positive association between early childhood teachers’ literacy-related content knowledge and the quality of classroom literacy practices. Piasta et al. (2020b) found that phonological awareness of print and letter knowledge practices was positively associated with literacy teaching practices. Explicit targeting of literacy content knowledge in pre-service early childhood preparation programs may increase high-quality literacy practices (Piasta et al., 2020a). Teacher preparation programs need to prepare teachers better to teach code-related literacy. However, this comprises more than just teaching linguistic knowledge; instruction must be adaptable and equitable (Tortorelli et al., 2021).

2.2. Picture Book Shared Reading in the Prior-to-School Years and Code-Related Literacy

Picture books consist of a medium (book) and images (pictures). Picture books are described as having a balance between visuals and texts, as opposed to an illustrated text where the text is more dominant than illustrations. However, picture books do not necessarily include text (Kummerling-Meibauer, 2017; Sipe, 2012). Picture books engage young readers and use pictures and text, together with a range of discursive registers, providing opportunities for early childhood teachers to engage children with more cognitively demanding inferential questioning (Nicolopoulou et al., 2023). There is also reasoning around perceptions of what is occurring in the text, code-related talk, and rich language that can positively impact expressive and receptive vocabulary (Mesmer, 2016). Components of code-related literacy include phonics, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness. Shared reading of picture books can also support code-related literacy learning. Cracking the code requires children to learn printed words and map these onto meaning (Castles et al., 2018).

Shared book reading in the early years supports children’s literacy development and academic achievement (Zucker et al., 2009, 2013). Children’s literature and shared reading are commonly included in early childhood literacy programs (Mesmer, 2016; Pentimonti et al., 2021; Zucker et al., 2009), and research shows a positive link between building early literacy skills and sharing picture books (Bradfield & Exley, 2020; Lefebvre et al., 2011). Shared reading of picture books occurs in early childhood prior-to-school settings (Campbell, 2021; Hindman et al., 2012; Mesmer, 2016; Pentimonti et al., 2021) and, therefore, picture books are an ideal literary resource for teaching code-related literacy and vocabulary. Although the shared reading of picture books usually centres on story content discussion and vocabulary (Zucker et al., 2009), adult–child shared reading also offers opportunities to develop phonics, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness (Justice & Ezell, 2004; Lefebvre et al., 2011).

Early childhood teachers model print concepts during shared reading, for example, how to track print, print direction, and messages in print and images (Gehsmann & Mesmer, 2023). However, the amount of shared book reading does not necessarily indicate an increased understanding of phonics. Children can often ignore alphabetic letters and written words unless specific attention has been drawn to print on the page, known as print-referencing (Justice & Ezell, 2004; Zucker et al., 2013). Early childhood teachers’ direct linking of phoneme–grapheme instruction to picture books can support children’s phonics and phonological awareness while fostering reading enjoyment (Cabell et al., 2019). Phonological awareness can also occur through the shared reading of quality children’s picture books by teachers, embedding instruction at the rhyme and syllable level (Lefebvre et al., 2011). In addition to developing alphabet knowledge, it is widely known that shared book reading can foster children’s vocabulary skills (Dickinson & Porche, 2011; Gehsmann & Mesmer, 2023; Zucker et al., 2013).

2.3. Shared Picture Book Reading and Preschool Vocabulary Development

Vocabulary, one aspect of oral language, is the knowledge of words and their meanings, and it plays an important role in developing early literacy skills. Language skills and vocabulary strongly predict reading comprehension (Cabell & Zucker, 2023). Exposure to rich and varied vocabulary in children’s picture books can support vocabulary development (Zucker et al., 2013). The benefit of supporting vocabulary development through shared picture book reading is the exposure to uncommon words, where new and unusual words can be extracted and discussed during shared reading (Gehsmann & Mesmer, 2023). Words in picture books can be broken down into Tier-1, Tier-2, and Tier-3 words. Tier-1 words are words used in an everyday context (e.g., play, go, cat, happy), and Tier-2 words are those where a child can draw on existing schema, such as a known synonym (e.g., resolve, compare, environment). Tier-3 words refer to content areas or are subject-specific (e.g., photosynthesis, sonata, isosceles). Early childhood teachers should initially identify common, uncommon, and targeted vocabulary, such as Tier-1 and Tier-2, to build vocabulary at the literacy planning level and before adult–child reading occurs (Mesmer, 2016). Vocabulary discussions around Tier-2 words, where teachers use child-friendly definitions and rich language explanations around words in picture books, support children’s language and literacy development (Mesmer, 2016).

Extratextual discussion by teachers when reading with children is also positively associated with children’s vocabulary development (Zucker et al., 2013), particularly when focusing on inferential learning, such as extended rich discussions around word meanings. When young children engage in these rich discussions, they acquire new words and their meanings and learn how words work, thus further developing phonemic and phonological awareness and other oral language skills (Hill, 2020). Understanding and catering for the knowledge and practices children need to become effective readers is vital. Building pedagogical practices that develop such knowledge and understanding requires teachers to adopt an informed and adaptive approach to teaching literacy.

2.4. Adaptive Literacy Teaching and Early Reading

Learning to read is a complex task. It is generally agreed that learning to read relies on acquiring concepts and understandings like oral language, vocabulary, alphabet and print knowledge, phonology, and word identification, among others (Hill, 2020). Of course, we cannot treat reading as an isolated set of skills and practices. Learning to read is reinforced and contributes to developing other literate practices, for example, writing, speaking, listening, viewing, and creating. The act of reading—constructing meaning from print and other symbols—is a multidimensional process that relies on a myriad of skills, both complex and cognitive, and is always “situated in and mediated by social and cultural practices” (Moje, 2018, p. 2).

To facilitate the development of the whole literate child in the early years, teachers and knowledgeable others (Vygotsky, 1978) are the best-suited to provide opportunities that nurture the complex array of literacy capabilities that harness collaborative interactions with “tools, texts, people and resources” (Woods & Comber, 2020, p. 2). In this way, early childhood teachers can adopt a comprehensive approach to literacy teaching and learning, recognising it as a social, cultural, interactive, and material practice that relies on an interlacing suite of skills and strategies. Such an understanding can be supported through an adaptive approach where teachers work as “adaptive experts” (Darling-Hammond & Oakes, 2019), paying attention to the different facets of learning to read, including being aware of children’s social and cultural needs as they learn.

The notion of an “adaptive expert” (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005) makes the distinction between adaptive and routinised teaching. Never routine means that teaching is constantly in flux, and any teaching moment encompasses a woven mat of content, learning needs, situations, challenges, and dilemmas (Darling-Hammond & Oakes, 2019). Teachers as adaptive experts develop the “ability to be flexible and innovative to solve problems and develop their knowledge further” (Ellis & Bloch, 2021, p. 2497) by employing a “wide repertoire of strategies that allows them to continually adjust their teaching based on student outcomes” (Darling-Hammond & Oakes, 2019, p. 13). When teachers work as adaptive experts, they rely on building “expertise, knowledge and competencies” (Darling-Hammond & Oakes, 2019, p. 13) to meet student needs and new challenges that are inherent in our highly dynamic, technologised, and connected world. As adaptive literacy experts, teachers weave through strategies and pedagogies that include explicit instruction, guided and independent practice, and collaborative and inquiry-based learning, balancing teacher- and student-centred approaches. An adaptive approach to teaching reading considers the wide repertoire of strategies that inherently build reading capacities, making accessible “multiple factors, various processes, and multiple sources of information to inform reading” (Compton-Lilly et al., 2020, p. 185). Such an approach flies in the face of the recent preoccupation with and push for reductive and narrow approaches that argue that “explicit decoding is the necessary route to comprehension (Ellis & Bloch, 2021, p. 157).

The development of the N-SIT tool in the present study, is contextualised in wider, recurring, continuing, and highly divisive and politicised debates about the teaching of reading. N-SIT aims to build teacher knowledge about reading and locate phonics teaching in authentic contexts relevant to children aged two to five years. The tool offers opportunities for teachers to closely observe children so that they can adapt with learners and teach them how to manipulate reading resources to engage and comprehend text and other symbols to make meaning (Compton-Lilly et al., 2023).

The N-SIT tool addresses the complex nature of learning to read by foregrounding explicit components of the reading process within authentic literature. It focuses teachers’ attention on word meaning, word patterns, phonics, and spelling through interaction with a picture book whilst instilling a love of reading. This is timely, as some studies suggest a possible drop in children’s reading for pleasure (Boardman, 2024; Pink, 2022).

The following two research questions are addressed in this study:

- What knowledge of teaching reading do pre-service teachers have in relation to shared book reading and code-related skills?

- How can a Non-Scripted Intentional Teaching (NSIT) tool support phonics-focused teaching through the use of quality children’s literature?

3. Methodology and Materials

3.1. Picture Book Selection

The quality picture books chosen for this study were selected based on nationally and internationally awarded picture books, as well as high-quality potential phonics and phonological awareness teaching, and vocabulary text and diversity, noting that the lexical reservoirs are recommended to include five or more words. Tier-3 words are usually nouns, and Tier-2 words are generally adjectives or verbs (Hoffman et al., 2015). The picture books were chosen based on receiving children’s literature awards or nominations, for example, The Children’s Book Council of Australia Picture Book of the Year Awards and The British Children’s Book Award. The picture books contained a synergistic blend of text and illustration (Hoffman et al., 2015; Sipe, 2012), thematically and language-rich, with Tier-1, Tier-2, and Tier-3 words that have complex meanings and include known and unknown words (Hoffman et al., 2015).

The N-SIT pre-service teacher books included Pig the Pug (Blabey, 2016), The Snail and the Whale (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2017), Grandpa and Thomas (Allen, 2005), and Where is the Green Sheep? (Fox & Horacek, 2004). Except for The Snail and the Whale, the picture books were awarded or nominated winners by the Children’s Book Council of Australia. All picture books are early childhood prior-to-school resources, commonly found in long daycare and preschool settings. All books were chosen for their Tier-1 and Tier-2 vocabulary and ability to teach code-related literacy (phonological awareness and phonics). The picture book, My Friend Fred (Watts & Yi, 2019), that will be discussed is a representative example of the N-SIT framework in action.

The N-SIT teaching model picture book My Friend Fred (Watts & Yi, 2019) was selected for the following attributes:

- Australian author and illustrator;

- The Children’s Book Council of Australia Winner: The Children’s Book of the Year Awards;

- Author Frances Watts is a multiple award-winning children’s book author. Illustrator A. Yi is an illustrator of the well-known and best-selling Alice Maranda series written by Jacqueline Harvey;

- Repetition for its essential literary devices, including adding rhythm, supporting narrative structure, and generating meaning (Gannon, 2009);

- Inclusion of rhyme and/or alliteration to support phonics and phonological awareness;

- Inclusion of Tier-1 (my, friend, loves, dog, tree) and more than five Tier-2 words (bored, sniffs, disgusting, rather, handsome). Excluding the 11 repetitions of “My friend Fred”, the text contained 45% verbs, 29% nouns and 4% adjectives. Note that Tier-3 words were not a priority for this study, as Tier-3 words are usually relevant for specific content areas and more often occur in non-fiction texts in the prior-to-school years.

3.2. Development of the N-SIT Pedagogical Tool

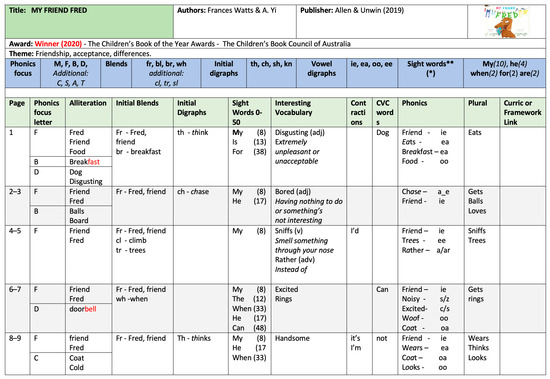

The N-SIT pedagogical tool was initially developed and trialled for early childhood educators teaching in the prior-to-school years. The N-SIT early childhood teacher pedagogical tool research, which was a preliminary observation and interview with an early childhood teacher, revealed the potential for the N-SIT to benefit pre-service early childhood teachers. Drawing on the feedback from the preliminary observation, the N-SIT pedagogical tool was adapted for PSTs (Figure 1). We then conducted the present pilot study with post-graduate early childhood teachers. A completed example of My Friend Fred functioning as an instructional model (Figure 2). The N-SIT pedagogical tool focuses on code-related literacy and vocabulary, and links to relevant early childhood frameworks.

Figure 1.

N-SIT Pedagogical Tool Template.

Figure 2.

N-SIT Instructional Model: My Friend Fred (Watts & Yi, 2019). ** Oxford Wordlist. (*) Oxford Wordlist Number.

The N-SIT is a living, working and evolving document that adapts to specific and authentic teaching contexts. Since the creation of the N-SIT and the trial with PSTs, the N-SIT will be amended further; for example, teachers who use a synthetic phonics approach, consonant blends, or consonant clusters as a unit are not taught separately, as sounds are taught through phoneme blending and segmenting of the individual phoneme–grapheme (Five From Five, 2025), and may not be required in the N-SIT tool. Therefore, this aspect could be removed from the N-SIT tool.

3.3. Pre-Survey and Post-Survey of Pre-Service Teacher Knowledge

Pre-N-SIT and post-N-SIT activity participant surveys were developed to ascertain PSTs’ knowledge of phonics, phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, and early literacy learning and teaching before and after engaging with the N-SIT pedagogical tool. The pre-test and post-test contained questions that focused on the same content. Of the 24 PST participants, 24 completed the pre-survey, and 17 completed the post-survey. To align with the appropriate terminology, the term ‘interesting vocabulary’ (Figure 2) was changed to ‘targeted vocabulary’ in the final N-SIT (Figure 3, see below).

Figure 3.

N-SIT for The Snail and the Whale (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2017). The student’s original handwritten N-SIT has been typed by the researchers to support readability.

The pre-N-SIT survey contained six Likert scale questions about how well-prepared they felt to teach literacy and their knowledge of phonics, phonological awareness, and vocabulary knowledge. Three open-ended questions asked participants to explain what they know about teaching early reading, describe a literacy teaching example they are familiar with, and describe what they would like to know about teaching literacy. The post-N-SIT survey contained four Likert scale questions about their knowledge of phonics and phonological awareness and one open-ended question asking the following specifically regarding the N-SIT: “In what way did the N-SIT support your understanding of code-related literacy and teaching vocabulary?”, “Was there an aspect of the N-SIT you found complex?”, and “What changes or refinements can you suggest for the N-SIT?” Pre- and post-N-SIT survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics. The responses to the surveys’ open-ended questions were analysed through reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022).

The completed N-SIT (Figure 3) demonstrates self-correction of incorrect initial blends, e.g., crossing out ‘sh-shark’, then rewriting ‘sh-shark’ into the initial digraphs column with one initial blend error (fo-formed) and initial digraph (fe-feather). The PSTs identified a phonics focus linked to alliteration and targeted vocabulary. Contractions, CVC, vowel digraphs, and curriculum links were not completed. This could be due to time constraints, as suggested by a post-survey respondent who felt a “little bit short on time” (Respondent 12). The PSTs’ errors provide their lecturers or teaching tutors with an assessment tool enabling targeted scaffolding and instruction.

3.4. The Study Setting and the Participants

Following university ethics approval (no. XXXX) to conduct the study, two early childhood (birth-to-eight) PST cohorts participated in the study. One group was enrolled in the first-year English and literacy unit, and one group of students were enrolled in a third-year English and literacy unit. All early childhood students attending tutorials participated in the N-SIT tutorial activity (internal and online cohorts), with 24 PSTs agreeing to participate in the study. Of the 24 participants, 12 were enrolled in the first-year unit and 12 were enrolled in the third-year unit. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary. The pre-and post-activity survey and engagement in the N-SIT literacy activity were part of the students’ usual tutorial activities during a teaching week focused on learning phonological awareness and phonics. To recruit participants an announcement regarding the study was added to the teaching unit website, along with N-SIT participant information and consent forms. The first-year students had recently completed an assessment task involving analysing and planning for teaching using children’s literature and understood the role children’s literature plays in supporting early literacy.

3.5. Data Collection

The data were collected during each (first and third year) of the two-hour online and face-to-face tutorial workshops. Most students knew the researchers as their current or former lecturers. A PowerPoint presentation and links to the survey were provided as an initial introduction. On campus face-to-face students were grouped into small table groups of three to four students. Online students worked independently. Time was allocated for participating students to complete the pre-survey before the commencement of the N-SIT activity lesson. The researcher gave each student an A3-sized blank N-SIT (Figure 1) and selected picture books. The researcher read My Friend Fred (Watts & Yi, 2019) to each tutorial student group and then presented the completed N-SIT (Figure 2) enlarged on the data projector. The researcher explained each category, defined phonics, and discussed phonological and phonemic awareness with worked examples. The example of the My Friend Fred (Watts & Yi, 2019) picture book was available to all students during the activity via an Interactive Smart Board at the front of the classroom. Upon completion of the activity, each group of participating students completed the post-N-SIT survey. During this time, students who had not consented to participate in the study worked on other unit-related activities. The student’s N-SIT work samples were analysed by the authors using qualitative methods of participant-written responses, with consideration of early reading theories/frameworks and the PSTs’ ability to identify a phonics focus, alliteration, digraphs, initial consonant blends, sight or high-frequency words, potential targeted vocabulary, and links to the EYLF Outcome 5 (AGDE, 2022) or the Australian Curriculum: English Foundation Year (The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, n.d.).

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Survey Data Analysis

The pre-survey was designed to examine PSTs’ understanding of early literacy skills (e.g., phonics, phonological and phonemic awareness, vocabulary) and the teaching of early reading (Table 1). The following responses explored their teaching knowledge by written responses describing what is most important in early reading instruction, a teaching example they have either learnt or thought was best practice in their previous teaching practicums, and a short Likert scale to identify correct code-related literacy definitions. The results are reported as follows:

Table 1.

Pre-Survey.

4.1.1. Likert Scale Reported Feelings of Preparedness to Teach Beginning Reading and Definitions

The survey asked the PSTs to identify the correct definition of phonics, phonological awareness, and phonemic awareness from multiple-choice answers with only one correct answer. Of the 27 responses, 100% of PSTs accurately defined phonics as matching letters of the alphabet with their corresponding sounds. When asked how alphabet knowledge is best taught, 75% (n = 18) reported through both reading and writing, 21% (n = 5) reported only through reading, and 4% (n = 1) were unsure. All third-year English students reported 100% accuracy in definitions.

Half of the PSTs could accurately identify the correct definition for phonemic awareness, as follows: 50% (n = 12), with 46% (n = 11) reporting the phonics definition, and 4% (n = 1) who were unsure. Only 21% (n = 5) could identify the correct response when asked to identify the most straightforward phonemic awareness task from a list of phonemic awareness tasks. Of the 27 PST responses, 50% (n = 12) accurately selected the correct definition for phonological awareness, with 50% (n = 12) selecting the definition for phonics. All third-year English students reported 100% accuracy in definitions and 21% correct responses to phonological awareness tasks.

The initial Likert scale and multiple-choice data revealed that the PSTs felt they were either well or somewhat prepared to teach vocabulary rather than phonics and phonological awareness. All PSTs understood phonics related to the association between letters and their sounds. Only half of the PSTs in this study could correctly define phonemic awareness and phonological awareness.

4.1.2. Pre-Survey Written Feedback

What is essential in teaching early reading?

The survey yielded 23 PST explanations of their current understanding of teaching early reading. Responses ranged from 14 to 56 words. Of the 23 written responses, 11 PST respondents reported an understanding that early reading involves a broad range of literacy areas, including phonics, comprehension, phonological awareness, fluency, and vocabulary, as the following statements suggest:

“Teaching early reading is, in general, focusing on comprehension vocabulary to understand the content of the story. Reading includes the knowledge of phonics vocabulary, comprehension and oral language” (Respondent 12);

“I know there are different parts and factors that compose students’ success in learning to read, such as phonological awareness, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension, teaching phonics” (Respondent 6).

Nine respondents also reported the importance of explicit and systematic instruction, including phonics and phonological awareness. The following statements are indicative of this view: “I understand that when teaching early reading, it is important to use an explicit approach…I also understand that I should use an explicit phonics program” (Respondent 1); “Early reading is a complicated task that requires explicit and systematic teaching” (Respondent 8); and “Teaching phonics is one of the prerequisites for children to learn to read, as they need to understand and be able to sound out alphabets in print in order to read” (Respondent 6).

Half of the PST respondents (n = 12) reported a more holistic view of early reading through shared songs, plays, connecting knowledge and interest, autonomy, language development, and reading for pleasure. This is evident in the following statements:

“Good experience with reading from a young age will make a foundation for their reading for pleasure in the future” (Respondent 15); “Educators connect play into learning and promote the language skills and other real knowledge” (Respondent 16); and “It is better to raise children’s interests” (Respondent 7).

These responses suggest that PSTs understand early reading but report different priorities regarding the most important one. Some PSTs prioritised the technicalities of reading, such as phonics and explicit teaching of phonological skills, whereas other PSTs reported a more holistic understanding of early reading, such as building foundations for reading for pleasure, telling stories through songs and plays, and improving social skills and critical thinking.

Explanations of what are considered by PSTs as examples of quality early reading teaching in classrooms?

The PSTs (n = 21) provided a range of appropriate early reading lesson ideas, ranging from 5 to 108 words. Only one PST responded that they did not know any teaching examples. Overwhelmingly, 76% of PSTs (n = 16) provided examples of teaching phonics, phonological awareness, and vocabulary through children’s literature. There were (n = 7) phonics lesson ideas, for example, “finger tracing letters…name recognition” (Respondent 1), “teach them the difference between upper and lower case (letters)” (Respondent 11), and “focus on the sound the letters make” (Respondent 19). Phonological awareness lesson ideas were reported by 20% (n = 4), for example, “repeat the word and clap hands to decode the syllables of the words” (Respondent 4).

Over half of the PSTs (61%, n = 13) described in-depth examples of teaching vocabulary. This is evident in the following examples:

One way I would teach is by reading a picture book to the students. I would then select a word that the students may be unsure of the definition of. I would then ask if anyone knows the definition. I would then explain what the word means and use examples of the children from the class using that word, e.g., if it was the word ‘auburn’, I would see if any child in the class has that colour hair “Sally has auburn hair”. I would then write the word out on a whiteboard and talk to the students about what letters they see and sounds they make.(Respondent 2);

When reading a book for a small group of children, emphasise the new vocabulary that the children might not seen/heard before by asking open-ended questions, explain the words, and provide examples(Respondent 12).

The range of different teaching examples reveals that the PSTs in this study understand the potential of children’s literature in planning lessons that can support children’s phonics, phonological awareness, and vocabulary learning. Four participants in this study did not provide a teaching example. The responses could indicate that the four PSTs may not know or feel confident giving an example.

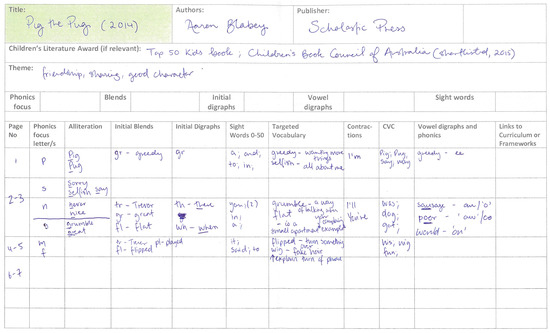

4.2. Implementation of the N-SIT During Tutorial Activities

The PSTs worked in small groups of four, reflected on their pedagogical decisions, and adopted a flexible and adaptive approach towards using the N-SIT tool. Observations of student engagement revealed collaborative learning, peer support, and students negotiating with each other to problem-solve and discuss literacy-focused concepts. Students’ verbal feedback included that the N-SIT experience was fun and enjoyable, the activity was practical, and the tutorial was the best literacy learning to date. The following are examples of completed N-SIT templates by PSTs during the tutorial activity for The Snail and the Whale (Donaldson & Scheffler, 2017) (Figure 3) and Pig the Pug (Blabey, 2016) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

N-SIT for Pig the Pug (Blabey, 2016).

The PST group in N-SIT Figure 4 completed the literature awards section and columns to curriculum frameworks with one initial digraph error ‘gr’. Like the example in Figure 3, the students could not complete the curriculum column, suggesting that more time may be needed, or they may not have known how to make these links. Lecturers or teaching tutors can scaffold learning with support in making links to early years frameworks and follow-up lesson planning.

4.3. Post-Survey Data Analysis

After completing the N-SIT tool tutorial experience, the PSTs were offered the opportunity to participate in a post-survey. Results revealed that 100% of PSTs responded with a correct definition of phonics both pre-survey and post-survey. Regarding correctly defining phonemic awareness, the post-survey revealed a decrease in incorrect responses from pre-survey (65%) to post-survey (35%). There was only a slight change in incorrect phonological awareness, with results from pre-survey at 50% and post-survey at 47% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Phonemic Awareness and Phonological Awareness Pre-Survey and Post-Survey Percentage Results.

The pre- and post-survey results suggest that PSTs had a clear definitional understanding of phonics. The N-SIT may have supported PSTs in an increased understanding of the term phonemic awareness and a slight understanding of phonological awareness. However, the results indicate that further scaffolding and explicit instruction on these terms are needed before and during the N-SIT activity, and as part of early childhood literacy units.

Post-Survey Written Data

The post-survey asked the PSTs how the N-SIT tutorial experience supported their understanding of code-related literacy. There were 17 responses, ranging from 10 to 55 words. The PSTs reported that the N-SIT tutorial experience supported their confidence in literacy teaching, provided an authentic guide for planning, and reinforced literacy knowledge in an enjoyable way. However, there were some areas of the N-SIT that PSTs found complex.

The N-SIT experience helped to increase PSTs’ confidence in teaching some early reading concepts. The following statements indicate this view: “It also eased my worries about the complexities of teaching literacy concepts to students in the classroom” (Respondent 3), “I feel as if I could use this on PEx (professional experience) confidently as feel I am specifically teaching early literacy skills” (Respondent 14), and “I found it empowering to learn a new way to teach the children” (Respondent 11), and “It (N-SIT) helped me to understand and gain a little confidence in the initial digraphs and blend differences.” “This N-SIT support is essential for future teachers” (Respondent 12).

The PSTs also reported that they found the N-SIT to be PST student-friendly, practical, and an enjoyable way to reflect on and consolidate early literacy knowledge, as the following respondents reported: “I actually found this really enjoyable and user-friendly and would use this in my future practice” (Respondent 16), “…also laid it out simply” (Respondent 11), and “It provides an explicit way for organising and teaching” (Respondent 5).

The N-SIT also supported an understanding of code-related literacy, as the following PSTs explained: “It opened my eyes further in identifying the elements of code-related literacy and teaching vocabulary” (Respondent 2), and “As a beginner to phonics, it helped to explain concepts, break them down, to connect with the literature” (Respondent 14).

The researchers also asked the PSTs if they found an aspect of the N-SIT complex. There were 16 responses with one word, “No” (Respondent 13), to 37 words. The respondents reported identifying initial digraphs and blends as the most challenging, but the N-SIT was supportive of learning. The following responses reflect this view: “identifying digraphs” (Respondent 2), “I found initial blends complex to determine whether the letters make that sound, or is there a sound they make with another letter (like st, sm, sl…)” (Respondent 3), and “At first, I had to figure out the difference between the initial blends and initial digraphs, but once I had worked that out, I was able to understand it very clearly” (Respondent 15).

The PSTs provided feedback on future refinements to the N-SIT tool. Most suggested they were sometimes confused about the difference between digraphs and initial consonant blends. One respondent pointed to having an additional prefix and suffix column to extend vocabulary lessons, and another suggested adding a column with an end digraph. One of the most important changes to be added was including a rhyme column. A group of students identified the absence of a column for rhyming words while working together during the N-SIT activity and brought this to the attention of the two research facilitators. A written survey response also identified this omission, stating, “Add a place for rhyming words because our book had a lot of rhyming words” (Respondent 16). This was important feedback for the researchers, given the number of children’s picture books containing rhyme and the importance of planning to support phonological awareness in the prior-to-school years. Another important change identified by a PST is to include a definition and exemplar for reference to assist future teachers in using the N-SIT resource.

The post-survey data and the PSTs’ N-SIT work samples identified that the N-SIT tool could support PSTs in further understanding how to plan for early reading through children’s literature in the prior-to-school years. Further explicit teaching of phonics, phonological awareness and phonemic awareness before, during, and after the N-SIT experience would be beneficial in supporting a more in-depth understanding of code-related literacy and how this can be supported in the year before beginning to teach in school. Respondents indicated that they would also like more content in their English and literacy units, as Respondent 7 indicated, “I would like a full unit targeting phonemes, so that not only for children but so we can learn about phonemes in an explicit and systematic way as well” (Respondent 7).

The above participant statements suggest that PSTs found blends and digraphs confusing. Current discussions around teaching phonics, specifically synthetic phonics, do not recommend teaching initial blends due to the amount of cognitive information children need to memorise when learning to read (Five From Five, 2025; Moats, 2020a, 2020b). Therefore, revised versions of the N-SIT need more explanation and identification of blends; furthermore, future research should consider why it is contested in current literacy teaching programs.

5. Discussion

To date, few studies, if any, have specifically explored potential strategies to support early childhood PSTs in developing their knowledge of teaching early reading and phonics with children aged from birth to eight five. However, many studies have explored PSTs’ early reading and code-related literacy knowledge (Meeks et al., 2020; Meeks & Kemp, 2017). Based upon government priorities and changes to ITE programs in English-speaking countries for the teaching of early reading in the classroom (Department of Education, 2023), the diverse phonics teaching practices in prior-to-school settings (Campbell, 2015), and the perceived lack of components of early reading, such as phonics and phonological awareness preparedness of PSTs (Meeks & Kemp, 2017; Weadman et al., 2021), the N-SIT has the potential to address the pressing need to discover innovative ways to support and train PSTs for effective reading instruction using authentic and positive tools and strategies. In particular, as PSTs’ knowledge and conceptions of reading development are still emerging in their early years of university study, designing strategies that integrate both shared book reading of quality children’s literacy and teaching code-related skills, such as phonics, would be invaluable. In addition, providing professional development in realising the potential of building vocabulary through shared picture book reading is crucial (Mesmer, 2016). Given that large-group, small-group, and one-to-one reading interactions between teachers and children are a common occurrence in a prior-to-school classroom (Gerde et al., 2016), the N-SIT may be useful for the planning and engagement of code-related literacy and vocabulary in ways that include quality children’s literature and potentially motivate children in their reading development.

The PSTs’ engagement with the N-SIT as a planning tool in combination with quality picture books (e.g., My Friend Fred) supported the analysis, identification, and mapping out of code-related skills (e.g., phonics, phonological awareness) within their chosen text. The PSTs identified targeted vocabulary in the picture books, noting that picture books provide rich and varied vocabulary (Zucker et al., 2013). The PSTs were supported in using the N-SIT tool for reflective planning and supporting beginning readers’ love of picture books. The teacher pre-survey found that most participants felt underprepared to teach phonics but felt more confident in teaching vocabulary than phonics skills. Developing confidence and growing knowledge and understanding of teaching reading by teachers in their training programs have been reported by previous studies (Bostock & Boon, 2012; Hendry, 2019; Meeks et al., 2020; Tortorelli et al., 2021). A key finding from N-SIT in the post-survey written feedback data was the increase in PSTs’ literacy planning confidence. Feeling underprepared is commonly reported by university students and is to be expected, especially in the initial years of PST training programs where students are rapidly learning a wide range of educational teaching, learning, and content and approaches across the pressures of several different curriculum areas.

The N-SIT tool has the potential to support PSTs in their teacher preparation programs for teaching reading. It could also be a useful resource for early literacy tutorial activities, as the tool supports the teaching of phonics that can be adapted to either synthetic or comprehensive phonics approaches. The PSTs reported the importance of systematic instruction, including phonics and phonological awareness, with all PSTs accurately defining the term phonics, indicating that they understood the important role phonics and phonological awareness play in early reading development. These findings differ from previous PST studies, finding reduced ability to define phonics and the importance of explicit and systematic code-related literacy instruction (Hendry, 2019; Meeks et al., 2020). The PSTs demonstrated direct linking of phoneme–grapheme opportunities and alliteration in the picture books, noting how both phonics and reading enjoyment can be planned as a joint positive experience (Cabell et al., 2019; Lefebvre et al., 2011).

Following the PSTs’ trial and implementation of the N-SIT tool during a university tutorial class, it was found that the participants’ knowledge of phonics and phonemic awareness was enhanced, and it helped them build a stronger understanding of the teaching of early literacy skills. Furthermore, there was an improvement in the PSTs’ understanding of the term phonological awareness; however, similar to Meeks et al.’s (2020) study, there were still a large number of PSTs who demonstrated limited phonological and phonemic awareness knowledge, confusing the terms phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, and phonics. These findings suggest that more focus is needed in supporting PSTs’ understanding of code-related literacy to be able to apply this knowledge to their planning.

The PSTs reported that the N-SIT was student-friendly and practical, and they enjoyed using the planning tool to unpack and critically analyse the selected texts of the picture books. They highlighted its usefulness in mapping phonics focus letters, associated blends, digraphs, plurals, and sight words from different picture books. As the PSTs collaborated in small groups, the NSIT activity also provided fruitful opportunities to discuss and complete an overarching evaluation of the book and identify key code-related skills and metalinguistic knowledge they could concentrate on during shared reading activities with emerging and beginner readers. These findings suggest that the N-SIT was particularly effective for collaborative planning phonics-focused teaching through children’s literature. The PSTs collaboratively approached the N-SIT activity, drawing on the notion of “adaptive experts” (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005), where they problem-solved, developed their knowledge as a small group, drawing on a repertoire of strategies, such as working together, collaborating, drawing on their existing understanding of code-related literacy, referring back to their course materials, and the pre-activity explicit instruction and training slides, peer learning, and questioning their tutors.

The PSTs provided critical feedback in the post-survey on using the N-SIT tool identifying the absence of columns, including rhyme, an important phonological component of early reading. It was interesting to note that although some participants were confidently able to describe engaging examples of planning activities with syllables and rhyme, they did not realise that these skills were, in fact, phonological awareness skills. The PSTs also suggested including a definition or exemplar to use as a resource. These findings are important for the improvement of the tool, and also as a way to support the development of PSTs’ metalinguistic skills and language.

In order to support PSTs’ teaching of reading to emerging and beginner readers, it is important to provide these university students with practical training tools such as the N-SIT, which can assist them in critically analysing a quality picture book and effectively utilising the text to support code-related skills such as phonics. This builds an understanding of the complex nature of learning to read and the crucial need for adaptive and flexible pedagogical practices (Darling-Hammond & Oakes, 2019). To assist in alleviating perpetual, contentious, and ongoing reading war issues (e.g., whole language versus phonics), it seems that blending both quality picture books and the critical analysis and identification of phonics skills embedded in these texts assisted in opening the eyes of the PSTs to an engaging pathway to plan for intentional teaching of phonics and vocabulary, alongside other important components of early reading skills. The N-SIT may provide a promising approach to teaching phonics; however, as the present study was a small trial with only a limited number of PSTs in one university, further work is needed to test the N-SIT with a larger participant sample, and with revised PSTs’ suggestions and in-depth pre-activity tutorials on phonological awareness and phonemic awareness. Future research is needed to examine how the N-SIT may fit within a synthetic phonics approach, and how the tool could be used for professional development to support teachers across various countries, such as Australia, the UK, and the USA, who require further knowledge and professional development training on how to effectively and authentically teach phonics with children in the prior-to-school years whilst engaging their love and motivation for reading.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. S.C., M.M.N. data curation S.C. and L.F., writing—original draft preparation S.C., M.M.N. and L.F., writing—review and editing, S.C., M.M.N. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted under the declaration of in according Queensland University of Technology Ethics Approval Number: LR-2023-6979-14253.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allan, J. (2024, June 13). Making best practice common practice in the education state. [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/making-best-practice-common-practice-education-state (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Allen. (2005). Grandpa and Thomas. Penguin Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2023, January 23). Mapping the updated EYLF to V9 Australian curriculum. Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/search?s=mapping+the+updated+EYLF+to+the+Australian+Curriculm_V2.0 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE]. (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. [Google Scholar]

- Blabey, A. (2016). Pig the Pug. Scholastic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, K. (2024, November 11). Children aren’t reading for pleasure according to new research—Here’s how you can help them love books. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/children-arent-reading-for-pleasure-according-to-new-research-heres-how-you-can-help-them-love-books-243108 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Bostock, L., & Boon, H. (2012). Pre-service teachers’ literacy self-efficacy and literacy competence. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 22(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, K., & Exley, B. (2020). Reading and viewing children’s picturebooks with grammar in mind. In A. Woods, & B. Exley (Eds.), Literacies in Early Childhood: Foundation for equity and quality (pp. 34–53). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cabell, S. Q., & Zucker, T. A. (2023). Using strive-for-five conversations to strengthen language comprehension in preschool through grade one. The Reading Teacher, 77(4), 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabell, S. Q., Zucker, T. A., DeCoster, J., Melo, C., Forston, L., & Hamre, B. (2019). Prekindergarten interactive book reading quality and children’s language and literacy development. Classroom organization as a moderator. Early Education and Development, 30(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. (2015). Feeling the pressure: Early childhood educators’ reported views about learning and teaching phonics in Australian prior-to-school settings. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(1), 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. (2020). Teaching phonics without teaching phonics: Early childhood teachers’ reported beliefs and practices. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 20(4), 783–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S. (2021). What’s happening to shared picture book reading in an era of phonics first? The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B. (2024, December 9). More support and better resources for phonics plus. Available online: https://premier.vic.gov.au/more-support-and-better-resources-phonics-plus (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2023). Strong beginnings: Report of the teacher education expert panel. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Compton-Lilly, C. F., Mitra, A., Guay, M., & Spence, L. K. (2020). A confluence of complexity: Intersections among reading theory, neuroscience, and observations of young readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. S1), S185–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton-Lilly, C. F., Spence, L. K., Thomas, P. L., & Decker, S. L. (2023). Stories grounded in decades of research: What we truly know about the teaching of reading. The Reading Teacher, 77(3), 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Oakes, J. (2019). Preparing teachers for deeper learning. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. (2024a). Choosing a phonics teaching program. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/choosing-a-phonics-teaching-programme/list-of-phonics-teaching-programmes (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Department for Education. (2024b). Early years foundation stage statutory framework: Setting the standards for learning, development and care for children from birth to five. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/670fa42a30536cb92748328f/EYFS_statutory_framework_for_group_and_school_-_based_providers.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Department of Education. (2022). Belonging, being & becoming: The early years learning framework. Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Department of Education. (2023). Quality initial teacher education review. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Dickinson, D. K., & Porche, M. V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading abilities. Child Development, 82(3), 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J., & Scheffler, A. (2017). The snail and the whale. Macmillan Children’s Books. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, C. (2023). Universities given two years to overhaul teaching degrees after education ministers’ meeting. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-07-07/review-of-university-teacher-degrees-at-ministers-meeting/102564402 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Early Childhood Australia [ECA] & Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2014). Foundations for learning: Relationships between the early years learning framework and the Australian Curriculum: An ECA-ACARA paper. Available online: https://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/ECA_ACARA_Foundations_Paper_FINAL-web.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Ellis, G., & Bloch, C. (2021). Neuroscience and literacy: An integrative view. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa, 76(2), 157–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Five From Five. (2025). Teaching consonant blends. Available online: https://fivefromfive.com.au/phonics-teaching/essential-principles-of-systematic-and-explicit-phonics-instruction/teaching-consonant-blends/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Fox, M., & Horacek, J. (2004). Where is the green sheep? Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon, S. R. (2009). One more time: Approaches to repetition in children’s literature. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 12(1), 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehsmann, K. M., & Mesmer, H. A. (2023). The alphabetic principle and concept of word in text: Two priorities for learners in the emergent stage of literacy development. The Reading Teacher, 77(2), 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H. K., Goetsch, M. E., & Bingham, G. E. (2016). Using print in the environment to promote early writing. The Reading Teacher, 70(3), 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Justice, L. M., Kaderavek, J., & McGinty, A. S. (2012). The literacy environment of preschool classrooms. Contributions to children’s emergent literacy growth. Journal of Research in Reading, 35(3), 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, H. (2019). Becoming a teacher of early reading: Charting the knowledge and practices of pre-service and newly qualified teachers. Literacy, 54(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S. (2020). Becoming a reader in the early years. In A. Woods, & B. Exley (Eds.), Literacies in early childhood: Foundations for equity and quality (pp. 193–208). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hindman, A. H., Wasik, B. H., & Erhard, A. C. (2012). Shared-book reading and Head Start preschoolers’ vocabulary learning: The role of book-related discussion and curricular connections. Early Education and Development, 23(4), 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J. L., Teale, W. H., & Yokota, J. (2015). The book matters! Choosing complex narrative texts to support literary discussion. YC Young Children, 70(4), 8–15. Available online: https://ezproxy.scu.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/book-matters-choosing-complex-narrative-texts/docview/1789780620/se-2 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2004). Print referencing: An emergent literacy enhancement strategy and its clinical applications. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 35(2), 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummerling-Meibauer, B. (2017). Introduction: Picturebook research as an international and interdisciplinary field. In B. Kummerling-Meibauer (Ed.), The routledge companion to picturebooks (pp. 1–8). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, P., Trudeau, N., & Sutton, A. (2011). Enhancing vocabulary, print awareness and phonological awareness through shared storybook reading with low-income preschoolers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11(4), 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, C., & Arrow, A. (2011). Literacy in the early years in New Zealand: Policies, politics and pressing reasons for change. Literacy, 45(3), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, L. J., & Kemp, C. R. (2017). How well prepared are Australian preservice teachers to teach early reading skills? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(11), 1–17. Available online: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol42/iss11/1 (accessed on 29 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Meeks, L. J., Madelaine, A., & Kemp, C. (2020). Research and theory into practice: Australian preservice teachers’ knowledge of evidence-based early literacy instruction. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 25(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer, H. A. (2016). Text matters: Exploring the lexical reservoirs of books in preschool rooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 34, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moats, L. (2020a). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3rd ed.). Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Moats, L. (2020b). Teaching reading is rocket science, 2020: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Available online: https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/moats.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Moats, L. (2025). Why have teachers been left unprepared to teach reading? Reading Rockets. Available online: https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/professional-development/articles/why-have-teachers-been-left-unprepared-teach-reading (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Moje, E. (2018). Conversation about the reading wars, sparked by a new documentary about literacy instruction: Q&A with Elizabeth Moje, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education: National Education Policy Center. Available online: http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/fyi-reading-wars (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Neumann, M. M., Hood, M., & Ford, R. (2013). Using environmental print to enhance emergent literacy and print motivation. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 26, 771–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M. M., Hood, M., Ford, R., & Neumann, D. L. (2011). The role of environmental print in emergent literacy. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 12(3), 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Government. (2023). Effective reading instruction in the early years of school. Available online: https://education.nsw.gov.au/about-us/education-data-and-research/cese/publications/literature-reviews/effective-reading-instruction-in-the-early-years-of-school (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Nicolopoulou, A., Hale, E., Leech, K., Weinraub, M., & Maurer, G. (2023). Shared picturebook reading in a preschool class: Promoting narrative comprehension through inferential talk and text difficulty. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofsted. (2012, November 16). Early language and literacy: From training to teaching. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-language-and-literacy-from-training-to-teaching (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Ottley, J. R., Piasta, S. B., Mauck, S. A., O’Connell, A., Weber-Mayrer, M., & Justice, L. M. (2015). The nature and extent of change in early childhood educators’ language and literacy knowledge and beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentimonti, J. M., Bowles, R. P., Zucker, T. A., Tambyraja, S. R., & Justice, L. M. (2021). Development and validation of the Systematic Assessment of Book Reading (SABR-2.2). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Park, S., Farley, K. S., Justice, L. M., & O’Connell, A. A. (2020a). Early childhood educators’ knowledge about language and literacy: Associations with practice and children’s learning. Dyslexia, 26(2), 115–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Soto, P. R., Farley, K. S., Justice, L. M., & Somin, P. (2020b). Exploring the nature of associations between educators’ knowledge and their emergent literacy classroom practices. Reading and Writing, 33(6), 1399–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, E. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs and intended practices around the promotion of reading for pleasure among primary children [Master’s thesis, Queensland University of Technology]. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/231720 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (2024). Queensland kindergarten learning guideline (QKLG). Available online: https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/kindergarten/qklg (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Queensland Government. (2024). Queensland’s reading commitment. Available online: https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/stages-of-schooling/queenslands-reading-commitment (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Queensland Government. (2025). Queensland’s reading commitment. Available online: https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/stages-of-schooling/queenslands-reading-commitment (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Roskos, K. A., & Christie, J. F. (2011). Mindbrain and play-literacy connections. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11(1), 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, L. R. (2012). Revising the relationship between text and pictures. Children’s Literature in Education, 43, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. W., Brady, J. P., & Anastasopoulos, L. (2008). Early language and literacy classroom observation scale, pre-K. Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (n.d.). English. F-10 version 9.0. Curriculum content F-6. Available online: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/content/dam/en/curriculum/ac-version-9/downloads/english/english-curriculum-content-f-6-v9.docx (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Tortorelli, L. S., Lupo, S. M., & Wheatley, B. C. (2021). Examining teacher preparation for code-related reading instruction: An integrated literature review. Reading Research Quarterly, 56, S317–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, F., & Yi, A. (2019). My friend Fred. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Weadman, T., Serry, T., & Snow, P. C. (2021). Australian early childhood teachers’ training in language and literacy: A nation-wide review of pre-service courses’ content. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(2), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, A., & Comber, B. (2020). Bringing together what we know about literacy and equity: A discussion about what’s important. In A. Woods, & B. Exley (Eds.), Literacies in early childhood: Foundations for equity and quality (pp. 2–15). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker, T. A., Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Pentimonti, J. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2013). The role of frequent, interactive Prekindergarten shared reading in the longitudinal development of language and literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1425–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, T. A., Ward, A. E., & Justice, L. M. (2009). Print referencing during read-alouds: A technique for increasing emergent readers’ print knowledge. The Reading Teacher, 63(1), 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).