Abstract

LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) was used to understand the ideals of connectivity and inclusivity among students, adult learners, and workers in a higher education community. While connectivity in nature’s ecosystem has been well studied, it is important to explore this form of connectivity among humans. The objectives of this study were to determine and analyze the main barriers and enablers of connectivity and inclusivity in higher education teaching, learning, and operations, and to propose key action plans. By using LSP in our study, we explored a kinesthetic approach where participants from diverse age groups (20–56 years) and professional/academic levels built models and shared their stories with others. An evaluation of the workshop was obtained using questionnaires (open-ended and scale-based surveys). All the participants found the LSP useful for the overall experience, indicating a strong overall support for its use. In total, 75% of the participants found it valuable and 50% of the participants found the process “difficult”, particularly in group communication and model representation, which require further refinement. Participants’ responses showed that both affective and cognitive elements were active during the workshop, suggesting that this method encourages all voices to be heard. In addition, the methodology for problem-solving and entertainment is a promising pedagogical and andragogical tool for teaching in higher education and in non-academic settings.

1. Introduction

In nature, connectivity refers to how easily plants and animals can move between different habitat patches, including movement into non-local ecosystems. This connectivity is crucial for ecosystem function and the flow of materials (ConnectGreen, 2021). Human activities are increasingly disrupting this natural connectivity, which, in turn, affects the abundance, distribution, and survival of various species (Crook et al., 2015). Learning from nature, we can see the importance of reducing barriers in human systems. In practical terms, strong human connectivity supports effective social interactions and adaptation to changing environments, with studies showing that good social ties contribute significantly to an improved mood and mental health (Martino et al., 2017). Connectivity has also been shown to be socially beneficial to businesses, as it accelerates human progress, improves Gross Domestic Product (Harish, 2016), and creates value to consumers, leading to higher profits (He et al., 2012).

Connectivity in natural ecosystems enhances the cycling of materials from one part of the system to the other, in which all-living things—humans, animals, and plants—depend. While ecological connectivity underpins species persistence and ecosystem resilience (Beger et al., 2022), human activities are changing connections within and between ecosystems over a wide range of spatial scales and habitat types, and these effects threaten the biota and the ecosystem (Crook et al., 2015). Maintaining a functional ecological connectivity would, therefore, protect the ecosystem humans depend on in the short and long terms (ConnectGreen, 2021). As humans are part of natural ecosystems and are not separate from them, long-term human sustainability hinges on the premise of protecting ourselves and nature (Lankenau, 2018).

Building connections with colleagues through meetings and social interactions promotes social learning, enhances understanding of complex interconnected problems, and helps individuals better appreciate each other’s perspectives. This improved mutual understanding strengthens workplace relationships and creates a foundation for sustainable collaboration and networking (Ridder et al., 2005). In higher education, fostering connections among students creates more engaging and relevant learning experiences. This approach helps learners appreciate the role of emotions in group work, understand diverse perspectives, and cultivate respect for diversity (Peabody & Turesky, 2018). Achieving this requires open, psychologically safe environments—often built through playful activities. As (Barton & Ryan, 2014) explains, playfulness breaks down barriers to participation and sparks curiosity and wonder, making learning more engaging. Incorporating playfulness into learning can help cultivate and strengthen connectivity, as it often involves experiential and collaborative activities. Experiential learning, which emphasizes hands-on kinesthetic experiences, becomes even more powerful when combined with social constructivist teaching methods (Barton & Ryan, 2014; Mobley & Fisher, 2014). Social constructivist approaches aim to expose students to diverse perspectives, encourage multiple ways of thinking and problem-solving, and foster a sense of ownership and self-awareness in the learning process (Schweitzer & Stephenson, 2008).

The LEGO® Serious Play (LSP) model has been adopted across both pedagogical and andragogical settings (Fry et al., 2009), especially with advanced learners (Dann, 2018; Hoskins & Newstead, 2009; McCusker & Swan, 2018; Peabody & Noyes, 2017). In higher education, LSP has been used in fields as varied as management (Benesova, 2023), leadership development with graduate students (Peabody & Turesky, 2018), academic librarianship (Wheeler, 2023), occupational therapy (Peabody & Noyes, 2017), fashion (James, 2013), and nursing (Stead et al., 2020), where it promotes peer interaction and the collaborative exploration of complex topics. By guiding participants through iterative cycles of building, storytelling, and reflection, LSP captures participants’ thoughts and feelings to drive experiential self-directed learning in the social, psychological, and connectivity domains (Peabody & Turesky, 2018). While LSP actively engages hands and minds in constructing visual models, it also fosters self-discovery (Regalado, 2015) and the sharing of visual metaphors through narrative—an approach shown to inspire, motivate, build trust, influence others, encourage reflection, and enhance interpersonal interaction (Dahlstrom, 2014). Moreover, this playful process gives participants ownership of their learning, boosts engagement, amplifies their “voice” in a shared space, and demonstrates respect for diverse cultural perspectives (Burk, 2000). This article presents LSP as an experiential constructivist method for reflecting on, learning about, and exploring connectivity and inclusivity (C & I) among adult learners with varied backgrounds and experiences.

The aim of this study is to explore and deepen our understanding of connectivity and inclusivity (C & I) in higher education by using LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) as a practical tool for co-created learning and problem-solving. The specific objectives of this study were to build models, share and discuss the stories behind these models, explore participants’ experiences of the model-building process, identify personal and group action plans, and draw conclusions about the concept of connectivity by using a qualitative analysis of the participants’ shared insights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

The LSP workshop adopted in this study aligns with the method used in (Dann, 2018; Peabody & Turesky, 2018; Wheeler, 2023) and a number of principles., i.e., the facilitator provided a brief overview of the exercise and participants were provided with a set of questions; they built models in response to the questions; shared stories with members of the group using their models; both facilitator and participants shared their insights; and the facilitator provided a summary of all the connecting ideas. Below is a flowchart that illustrates each key step of the workshop:

A [Facilitator provided a brief overview, and the participants received a set of questions]

B [Build models in response to questions]

C [Share model’s meaning and story with the group]

D [Facilitator and participants crystalize insights]

E [Facilitator provides summary of connections]

F [Visual storytelling and phenomenological methods to gather deep qualitative data]

G [Analyze stories, perceptions, written feedback and questionnaires]

A --> B

B --> C

C --> D

D --> E

E --> F

F --> G

The flowchart captures the sequential flow of the process while emphasizing the collaborative and reflective nature of the study, incorporating both the creative and analytical aspects of the methodology. The exercises were time-bound for a duration of one and a half hours.

The facilitator also provided instructions for shared engagement in open and safe spaces for confidentiality and inclusion. The ground rules for the exercise emphasized the role of mutual communication, i.e., a culture of giving and sharing information to promote balanced interactions and engagement among the participants.

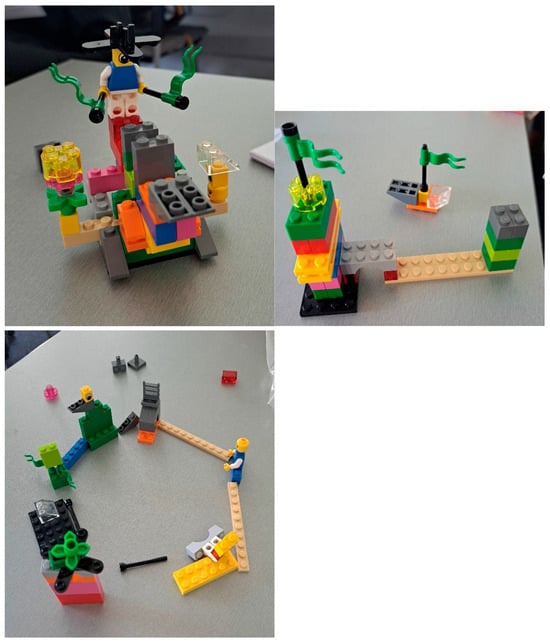

By using visual storytelling after model building (Figure 1), along with participants’ sharing of their experiences using phenomenological methods (Lester, 1999), helped to gather rich in-depth information and insights. The qualitative data collected included personal stories, perceptions, written feedback, and questionnaire responses, all of which were analyzed to explain the dynamics of the models and the nature of participants’ contributions.

Figure 1.

Models built by participants in response to questions.

The workshop questions were arranged into two parts. Part 1 constituted three open-ended questions which were designed as a follow-up to the two previous connectivity and inclusivity workshops (Medupin, 2023, 2024) held in 2022 and 2023. The questions asked were as follows: (a) What are the barriers to connectivity and inclusivity in higher education? (b) What are the enablers connectivity and inclusivity in higher education (c) What are your key action plans from connectivity with LSP? The responses to these questions were collated and sorted into sub-themes based on the similarity of participants’ responses. Three open-ended questions were asked based on three themes as follows:

- Experience with LSP representation: Please share your experience of representing your answers using LSP.

- Application of lessons learnt: Can you relate the lessons learnt from sharing with LSP to any proposed review in your teaching, research, or other professional activities?

- Workshop feedback: Share how the settings and approach for the workshop can be improved.

For the Part 2 questions, there were a mixture of ten closed and open-ended questions, rating survey questions based on participants’ feedback on their experience of LSP. The participants were asked to rate five items based on a three-point scale (see Table 1). The three-point scale was applied in this study to make the survey easier for the respondents to complete and to provide perspectives on LSP.

Table 1.

Participants’ responses using a three-point Likert-type scale. For each item, the scale is tailored to reflect a specific dimension of evaluation. The rating options are coded numerically from 3 to 1, with 3 generally indicating a less favorable or more moderate perception and 1 representing the most favorable evaluation.

2.2. Participants

Eighteen people (seven males and eleven females) participated in the workshop. These people included undergraduate students (n = 3), early career researchers (n = 2), non-academic professionals (n = 5), and academics (n = 8) who participated in the workshop and shared reflections in groups of from five to seven. The participants’ organizations included universities in the United Kingdom and institutions from the Global South, professional science organizations, private businesses, Non-Governmental Organizations, the National Environmental Research Council for Engaging Environments, and from charitable and religious organizations. The purpose of the small sample was to understand the experiences of diverse learners as they were immersed in a group process activity for a duration of an hour-and-a-half-long session. The participants approved the use of their responses from the questionnaires for the purpose of this publication.

3. Results

In Section 3.1, we present participants’ responses to the questions asked during the LSP workshop. In Section 3.2, we share their responses to open-ended questions completed after the workshop, along with the results of the overall evaluation. Eighteen participants took part, but response rates varied by question: for the questions on barriers to C & I, all 18 participants responded, seven participants responded to the enablers of C & I, and most participants devised unique key action plans after the LSP workshop.

3.1. The Responses to Questions During the Workshop

- Question 1: What are the barriers to effective connectivity and inclusivity in higher education?

The participants collectively provided twenty-one responses, which we organized into four barrier types. The categorized barriers highlight multiple factors affecting engagement and participation and provide a clear structure for designing targeted interventions.

- Institutional barriers:

- Physical and infrastructural limitations: Issues like unfriendly institutional policies, limited understanding of inclusion, and duplicity of issues.

- Challenges posed by the academic hierarchy and physical separation of staff at different buildings, which makes social interaction (e.g., obtaining coffee) inconvenient.

- Time and resource constraints: Overloaded time commitments making non-funded activities, such as academic social interactions, difficult.

- Communication barriers:

- Ineffective information-sharing: Poor communication, leading to the isolation of staff and students; difficulty in finding relevant information; uncertainty about whom to contact.

- Leadership and engagement challenges: Lack of senior management’s willingness to engage with the community; a general reluctance to participate in challenging discussions.

- Resistance to change:

- Maintaining the status quo: Some responses indicated that some individuals preferred existing conditions, demonstrating an unwillingness to adapt policies to evolving circumstances.

- Personal and cultural barriers:

- Self-confidence and individual differences: Issues such as imposter syndrome, shyness in expressing opinions, and personal mental health challenges.

- Cultural and empathy factors: Difficulties in understanding cultural differences; limited empathy; the impact of broader societal expectations on individual behavior.

- Question 2: What are the enablers of connectivity and inclusivity in higher education?

There were seven responses provided by participants which were categorized by the authors into four groups as follows:

- Promote connectivity via the following:

- Building bridges: Creating opportunities for collaboration and shared activities, e.g., interdepartmental workshops and seminars.

- Inclusive actions: Implementing strategies that are non-divisive and welcome everyone.

- Identifying gaps: Addressing disconnections in student engagement during teaching and learning.

- Building networks: Fostering networks and provide orientation for new staff.

- Improved communication and accessible information: Enhance communication channels to ensure information is made available to all.

- Identify and recognize leaders who are approachable and can positively influence others within academic spaces.

- Cultivate virtuous qualities, e.g., empathy, humility, kindness, and active listening to foster an empathetic community.

- Question 3: What are your key action plans following your connection with LSP?

The participants provided fourteen action plans based on their experiences with LSP. The authors categorized these responses into three sub-groups: promoting an inclusive culture, fostering personal and professional connectivity, and engaging others.

- 1.

- Promote an inclusive culture via the following:

- Learning from others: Learning about other people’s journeys, experiences, the knowledge they have acquired, and being willing to ask.

- Tailoring opportunities: Recognizing that everyone is at different stages of their journeys, and building supportive environments.

- Enhanced knowledge sharing: Fostering knowledge sharing and increasing undergraduate involvement in academia through attendance at social events and at laboratory meetings.

- Reflection: Making time to reflect on projects or teaching and question if they are connected and inclusive.

- Diverse opportunities: Identifying possibilities for improvement or development. Seeking opportunities to implement the lessons learnt from ongoing projects.

- 2.

- Promote connectivity and 3. engage others via the following:

- Encouraging institutional connectivity through adapting an inclusive culture and patterns of leadership.

- Celebrating team efforts and identifying quick wins.

- Involving the entire team: Take practical steps and actions to get team members on board.

- Embracing unlearning and relearning: Acknowledge that difficult lessons will be learnt and that difficult decisions will be made.

- Enhancing personal well-being through self-care.

- Strengthening existing connections.

- Actively seeking help: By asking for help, personal connectivity is improved.

- Promoting mentorship, continued learning through further training and skills development.

- Making teaching engaging.

3.2. The Post Workshop Responses to Questions and Evaluation Results

Table 2 shows participants’ responses based on open-ended feedback questions.

Table 2.

The participants’ responses to three open-ended feedback questions are presented.

The workshop evaluation revealed how participants experienced and assessed the LSP session across several key dimensions:

- Overall usefulness: All participants (100%) rated the LSP workshop as useful or extremely useful for their overall experience, particularly in exploring issues of connectivity and inclusivity. This unanimous positive response indicates a strong perceived benefit of the workshop’s methodology.

- Addressing challenging questions: When asked about the effectiveness of LSP in tackling challenging professional questions, 75% of the participants found it valuable, while the remaining 25% considered it only slightly valuable. This suggests that most participants see LSP as a beneficial tool in professional problem-solving, although a minority felt its impact to be limited.

- Information sharing within a group: The responses were mixed regarding the use of LSP for sharing information: 50% of respondents rated it as unhelpful, 25% found it helpful, and 25% remained neutral. This distribution indicates that while LSP was well received in some respects, its role in facilitating group communication may require further improvement.

- Lessons learnt through sharing: In total, 75% of the participants affirmed that they learnt lessons by sharing their answers using LSP, while 25% did not feel they gained these insights. The response of the majority highlights that the process of using LSP was not only engaging, but also educational.

- Ease of representing answers with LSP: The participants’ experiences with representing their answers using LSP were divided: 50% found the process difficult, 25% felt neutral about it, and 25% found it easy. These findings suggest that while LSP can be a powerful tool for representation, half of the participants encountered challenges in using it, which might suggest additional support or training for participants.

- Timing of the workshop: Regarding the workshop’s duration, 25% of participants felt that the timing was too short, whereas 75% were neutral about it. This indicates that while a quarter of the group may benefit from a longer session, the majority did not have significant concerns about the allotted time.

The evaluation reveals a strong endorsement of LSP for enhancing overall experience and exploring key questions of connectivity and inclusivity. However, mixed opinions on group information-sharing and the perceived difficulty in representing answers suggest that there are specific aspects of the workshop that could be refined to better support all participants.

4. Discussion

This study explores our understanding of connectivity and inclusivity (C & I) in higher education by using LSP as a tool for co-created learning and problem-solving.

4.1. The Barriers to C & I in the Academic Community

The barriers to effective C & I identified in this study highlight the multifaceted nature of the disconnections inherent within higher education institutions. These include institutional barriers, lack of effective communication, resistance to change in policies, and personal and cultural barriers. Institutional barriers emphasize strong physical and structural limitations, which allude to the role of higher education institutions being influenced by market-based policies. The drive for competition between and within institutions and the increasing workload based on the demand for excellence in teaching and research have contributed to widening the gaps between higher education staff, students, and leadership. This fact is supported by the author of Universities Under Fire, Jones (2022). The tendency, therefore, for institutions to resist change is supported by Shore and Taitz (2012), who traced this rise to the increasing emphasis placed on enterprise and money-making initiatives by both government and universities. In addition, institutions risk maintaining silos that not only stifle collaboration and innovation within academia, but which extend beyond the higher education community. By creating silos, the reluctance to challenge existing norms is a significant barrier to fostering connectivity. With increasing demand placed on higher education institutions, staff and students feel isolated and unsupported, exacerbated by poor information dissemination, leading to rising mental health challenges among members of the academic community. Participants cited imposter syndrome, mental health challenges, and cultural misunderstandings as barriers to connectivity. These barriers are well-documented in the literature on academia (Morris et al., 2022). For example, challenges of imposter syndrome in UK higher education was explored by Cristea and Babajide, stating, in their article, on pp. 56–67 (Morris et al., 2022), that academic institutions, once considered to be intellectual environments for knowledge acquisition and dissemination, are no longer supportive environments. These challenges emerged with increasing academic competition, divergence between self-identity and academic misrepresentation, a feeling of not belonging to the space, and the illusion of incompetence (see Butler in pp. 37–53 (Morris et al., 2022)). With imposter syndrome highly prevalent among early career academics compared to more senior academics, Cristea and Babajide found a correlation between imposter syndrome and poor psychological well-being and job dissatisfaction. These challenges, in addition to cultural misconceptions, could exacerbate mental health challenges, leading to feelings of uncertainty, lack of authenticity, insecurity, and anxiety among members of higher education communities. Figure 1 in Naylor and Mifsud (2019) displays a series of internal structural inequalities in higher education that affect students and staff, such as administration and the physical environment. These rising systemic and structural features in academia place a pressure that perpetuates exclusion and disconnections in higher education.

Although the LSP participants recognized time and resource constraints as inhibitors to participation in community-building activities based on these challenges, they reinforced the notion that academic workloads limit opportunities for meaningful interactions. Recognizing that time spent listening and learning from diverse perspectives could empower individuals to connect and solve problems in non-threatening, inclusive environments. (Peabody & Noyes, 2017; Stead et al., 2020) observed that the process could serve as an invaluable andragogical and pedagogical tool in fostering learning, as well as improve learners’ unique contextual knowledge and experience.

4.2. The Enablers of C & I in the Academic Community

Participants identified several factors that could enable the effective C & I necessary to overcome the previously mentioned barriers. These responses were organized into four main themes: promote connectivity, improve communication and make information accessible, recognize leadership in spaces, and cultivate virtuous qualities. Encouraging effective collaboration and advancing opportunities to welcome new entrants academia were seen as crucial to building inclusive networks. These responses align with (Naylor & Mifsud, 2019)’s case studies carried out among Australian higher education students and academics. (Naylor & Mifsud, 2019) identified structurally enabling approaches necessary to dismantle barriers and structural inequalities, including the need to build capacity for staff, use a blended approach to teaching which can help reduce inequities among students, and include students as co-designers to the curriculum. The authors argued that maintaining ongoing positive interactions around expectations through a variety of communication channels, actively operationalizing feedback on administrative processes, and enacting institutional will in leadership could facilitate effective engagement. These suggestions echo our LSP respondents’ view that clear, accessible communication benefits everyone and ensures that no-one is left behind. Furthermore, identifying visible, approachable role models in various settings of higher education can strengthen connectivity. Such leaders exemplify positive behaviors, promote professional identity development, and, through mentorship, cultivate strong working alliances. Naylor and Mifsud (2019) call this the distributed leadership model, which allows for more effective change, builds greater capacity, and improves decision-making.

Empathy, humility, and kindness emerged from the participants as foundational cultural values. Empathy, which could be both the cognitive or affective understanding of others, fosters belonging and underpins an inclusive institutional culture. The author (Gordon, 2018) emphasizes empathy as central to our humanity and advocates the need to cultivate active listening within educational settings.

4.3. The Key Action Plans Following the LSP Workshop

Participants’ action plans fell into three themes: promoting an inclusive culture, fostering both personal and professional connectivity, and actively engaging others. These themes reflect LSP’s core principles of reflection and co-construction of meaning. Reflection through the systematic examination of ideas in sequence and viewing them from multiple angles ensures that no critical insight is overlooked, making it a vital experiential learning tool, e.g., see (Mojsoska-Blazevski, 2012). Learning from others’ experiences, tailoring support, and boosting student engagement exemplify equity-minded practice. When people are given time to listen to others’ personal stories and reflect, their thinking shifts from a surface level to a deeper, action-oriented approach, fueling concrete planning and meaningful change. Multiple studies, such as (Ali & Sichel, 2018; Deacon, 1945; Edell, 2018; Martino et al., 2017; Peabody & Noyes, 2017; Peabody & Turesky, 2018; Wheeler, 2023), confirm that active engagement combined with reflection helps participants cultivate a genuine sense of shared humanity. Participants outlined some action plans to celebrate key contributions and actively involve team members. In her Forbes Communication Council newsletter, ‘The Power Of Celebrating Success In The Workplace’ (Leibtag, 2023), Leibtag argues that mutual celebration reframes how we share and recognize success, strengthens team bonds, fosters a genuine sense of belonging and helps colleagues to feel valued and appreciated (See https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescoachescouncil/2025/04/18/14-reasons-why-nonpromotional-thought-leadership-is-so-valuable/ (accessed on 25 January 2024)). In addition, the participants mentioned that they would actively maintain physical and mental health to reduce stress, combat feelings of imposter syndrome, and prevent burnout; these are common challenges faced by members of the academic community (Orsini, 2023). Furthermore, actively seeking help and fostering connections are vital in countering isolation.

4.4. Responses to the Open-Ended Feedback on LSP

Participants’ open-ended feedback revealed a diverse range of LSP experiences that closely align with the established principles of experiential and constructivist learning.

The experience of representing answers using LSP showed that many participants initially found it difficult to translate abstract ideas into physical LEGO® models. However, this very challenge created a welcome “break from routine” that stimulated creative thinking. Constructivist theory holds that learners build the deepest understanding when they engage in hands-on activities and then reflect on them (Buskes et al., 2009; Phillips, 1995; Prince, 2004). Furthermore, research shows that manipulatives like LEGO® pieces help externalize internal thought processes, encouraging reflection and deeper comprehension (Allen & Hartman, 2009; Jenkins, 2013). Although the shift from abstract concept to concrete forms demands a new way of thinking, mastering it supports cognitive development. Once participants overcame their initial hesitation, they reported the process as both engaging and enjoyable, echoing studies that playful, creative tasks can enhance learning and spark innovation by activating multiple modes of thinking (James, 2013; Peabody & Noyes, 2017). While the study objective was to co-address key questions on connectivity and inclusivity in higher education with diverse age groups and professional and academic levels, we observed that participants’ experiences differed with the use of LSP. (Vergara et al., 2023)’s study showed that understanding player profiles could significantly influence participants’ experiences and the results obtained while learning through play.

Many participants recognized that the techniques and insights gained through LSP could be applied to a variety of professional contexts, from teaching and research to strategic planning and leadership. The literature on LSP and experiential learning consistently points out that LSP can facilitate reflective dialog and collaborative problem-solving, making it an effective tool for group learning and team building. Although other educational practices, such as role-playing, simulate real-life scenarios, foster communication, team work, and the development of practical skills among participants (Rao & Stupans, 2012), LSP provides a structure for exploring multiple perspectives, including addressing complex ideas, problem-solving, building consensus, and fostering creativity by all, and these benefits are echoed in studies on collaborative learning (Benesova, 2023; Ridder et al., 2005). The process of externalizing thought through model-building can serve as a catalyst for strategic planning. For instance, leaders may use such methods to visualize complex problems and explore innovative solutions, a process supported by research on visualization and strategic thinking (McCusker, 2020; Peabody & Turesky, 2018). In addition, the use of LSP as an icebreaker or collaborative tool can help reduce barriers, especially for individuals who might initially feel alienated by unconventional teaching methods. Some responses suggested that the insights from LSP sessions could inform better data-driven strategies; this is a concept increasingly endorsed in both the educational and professional development literature.

To enhance the LSP workshop, participants recommended lengthening the initial phase to allow for more time for exploration and unstructured play. Experiential learning theory shows that this “play period” lowers barriers to connection and helps learners—especially those new to LSP—to become comfortable with the medium (Peabody & Noyes, 2017). Play-based learning research equally highlights how unstructured time fosters creative and critical thinking (Holliday et al., 2005; Wheeler, 2023). Finally, incorporating more group-based model-building activities aligns with collaborative learning principles: social interaction not only cultivates a shared understanding and collective creativity, but also supports each individual’s active construction of knowledge (Ridder et al., 2005).

4.5. Evaluation of the LSP Workshop

The LSP methodology received overwhelmingly positive feedback for enhancing engagement and reflection on complex issues. One hundred percent of the participants found it useful for engaging complex issues and seventy-five percent rated it valuable for tackling difficult questions. Its participatory and reflective format enabled groups to identify the barriers and enablers of C& I in higher education and bring abstract ideas to life, further boosting engagement (see Figure 1 and Table 1). These results mirror earlier findings (Peabody & Turesky, 2018; Dann, 2018; Peabody & Noyes, 2017; Wheeler, 2023) and demonstrate how LSP fosters a shared sense of humanity (Ali & Sichel, 2018; Deacon, 1945; Martino et al., 2017). Furthermore, by connecting cognitive and affective processes through collaboration, participants exhibited key traits of effective, strategic leaders (McCusker, 2020; Peabody & Turesky, 2018).

Seventy-five percent of participants reported that learning through model-sharing demonstrated LSP’s strength as a collaborative learning tool. However, several challenges emerged, as shown in Section 3.2. The feedback was mixed regarding LSP’s ability to facilitate group discussion, underscoring the importance of a robust debrief and, as noted by (Dann, 2018), allocating additional warm-up time to build participants’ confidence. With regard to timing, some participants indicated that extending the workshop would allow for deeper reflection. Previous research (Wheeler, 2023) confirms that striking the right balance between building, sharing, and reflecting demands both enough time and skilled facilitation.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights significant barriers and actionable pathways for enhancing connectivity and inclusivity in higher education. Institutional, communicative, personal, and cultural barriers must all be addressed through empathetic leadership, the intentional design of inclusive spaces, and support for effective connectivity. The use of LSP provides a novel and effective platform for engaging participants in complex discussions, although refinements are needed to support inclusivity in model expression and group communication. Following the responses provided by the participants, LSP presents an initial learning curve, but it ultimately offers significant benefits in fostering creative, reflective, and collaborative thinking. In addition, the problems were solved through the sharing among the participants, which led to the provision of key action plans. These observations are well-supported by the literature on experiential learning, constructivist education, and collaborative problem-solving. As observed in the workshop, the integration of physical and creative methodologies like LSP in professional and educational settings can lead to improved engagement, better conceptual understanding, and more innovative problem-solving approaches. Embedding these insights into institutional practice is essential for transforming academic cultures.

6. Limitations of the Study and Recommendations

This study relies on a small sample size. Although qualitative research methods provide a deeper understanding of experiences through the lens of a few individuals, they may not generally represent the experience of all the participants. Future research should examine how participants’ player profiles influence their experiences, engagement, and motivation with LSP. Understanding these profiles could inform the design and facilitation of the learning activity. Further studies could involve a larger sample size. Also, interviewing the participants as a follow-up to the questionnaire would provide more depth to the information gathered from the participants.

Author Contributions

The topic was conceptualized by C.M. and C.R.; written, and interpreted by C.M. It was reviewed and edited by C.M., C.R. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by an award received from the University of Manchester.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during the study were utilized in the preparation of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the participants at the workshop on connectivity and inclusivity in higher education—a solutions-based approach toward environmental sustainability whose contributions led to the report—to the funders of the project, the National Environmental Research Council (NERC) Engaging Environments, and to the anonymous reviewers whose feedback improved the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Author C.R. was employed by Tekiu Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, A., & Sichel, C. E. (2018). Humanizing the scientific method. In N. Way, A. Ali, C. Gilligan, & N. Pedro (Eds.), The crisis of connection: Roots, consequences, and solutions (1st ed., pp. 211–228). New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S. J., & Hartman, N. S. (2009). Sources of learning in student leadership development programming. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(3), 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G., & Ryan, M. (2014). Multimodal approaches to reflective teaching and assessment in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 33(3), 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beger, M., Metaxas, A., Balbar, A. C., McGowan, J. A., Daigle, R., Kuempel, C. D., Treml, E. A., & Possingham, H. P. (2022). Demystifying ecological connectivity for actionable spatial conservation planning. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 37(12), 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesova, N. (2023). LEGO® Serious Play® in management education. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2262284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, N. M. (2000, November 8–12). Empowering at-risk students: Storytelling as a pedagogical tool. Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association (86th), Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Buskes, G., Shen, B., Evans, J., & Ooi, A. (2009). Using active teaching workshops to enhance the lecture experience (pp. 67–72). Available online: https://ucd.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/professional/docview/855550030?accountid=14507%5Cnhttp://jq6am9xs3s.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/Australian+Education+Index&rft_va (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ConnectGreen. (2021). Ecological connectivity, the web of life for people and nature. Available online: www.interreg-danube.eu/connectgreen (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Crook, D. A., Lowe, W. H., Allendorf, F. W., Eros, T., Finn, D. S., Gillanders, B. M., Hadwen, W. L., Harrod, C., Hermoso, V., Jennings, S., Kilada, R. W., Nagelkerken, I., Hansen, M. M., Page, T. J., Riginos, C., Fry, B., & Hughes, J. M. (2015). Human effects on ecological connectivity in aquatic ecosystems: Integrating scientific approaches to support management and mitigation. Science of the Total Environment, 534, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M. F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 13614–13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, S. (2018). Facilitating co-creation experience in the classroom with Lego Serious Play. Australasian Marketing Journal, 26(2), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, G. (1945). The science of human relationships. Nature, 155(3944), 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edell, D. (2018). “We don’t come from the same background … but I get you”: Performing our common humanity by creating original theater with girls. In N. Way, A. Ali, C. Gillian, & P. Noguera (Eds.), The crisis of connection: Roots, consequences and solutions (1st ed., pp. 363–379). New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., & Marshall, S. (2009). Understanding student learning. In H. Fry, S. Ketteridge, & S. Marshall (Eds.), A handbook for teaching and learning: Enhancing academic practice (3rd ed., pp. 8–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M. (2018). Empathy as strategy for reconnecting to our common humanity. In N. Way, A. Ali, & P. Noguera (Eds.), The crisis of connection: Roots, consequences, and solutions (1st ed., pp. 250–273). New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, J. (2016). Human connectivity: The key to progress. Cadmus, 3(1), 77–83. Available online: http://cadmusjournal.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- He, T., Kuksov, D., & Narasimhan, C. (2012). Intraconnectivity and interconnectivity: When value creation may reduce profits. Marketing Science, 31(4), 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, G., Statler, M., & Flanders, M. (2005). Developing practically eise leaders through serious play. Consulting Psychology Journal, 59(2), 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, S. L., & Newstead, S. E. (2009). Encouraging student motivation. In H. Fry, S. Ketteridge, & S. Marshall (Eds.), A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice (3rd ed., pp. 27–39). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A. R. (2013). Lego serious play: A three-dimensional approach to learning development. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D. M. (2013). Exploring instructional strategies in student leadership development programming. Journal of Leadership Studies, 6(4), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. (2022). Universities under fire hostile discourses and integrity deficits in higher education (U. Smyth, & John University of Huddersfield Eds.). Palgrave critical university studies. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau, G. R. (2018). Fostering connectedness to nature in higher education. Environmental Education Research, 24(2), 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibtag, A. (2023, April 18). The power of celebrating success in the workplace. Forbes Communication Council. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescoachescouncil/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lester, S. (1999). Introduction to phenomenological research. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 25(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, J., Pegg, J., & Frates, E. P. (2017). The connection prescription: Using the power of social interactions and the deep desire for connectedness to empower health and wellness. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 11(6), 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, S. (2020). Everybody’s monkey is important: LEGO® Serious Play® as a methodology for enabling equality of voice within diverse groups. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 43(2), 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, S., & Swan, J. C. (2018). The use of metaphors with LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® for harmony and innovation. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 5(4), 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medupin, C. (2023). Connectivity as an antidote to fragmentation: Connectivity and Inclusivity (C & I) in higher education a solutions-based approach from environmental sustainability. Available online: https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=67537 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Medupin, C. (2024). To be an agent of change, you need to understand your evvironment: Connectivity and Inclusivity (C & I) in higher education a solutions-based approach from environmental sustainability. Available online: https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=73221 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Mobley, K., & Fisher, S. (2014). Ditching the desks: Kinesthetic learning in college classrooms. The Social Studies, 105(6), 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojsoska-Blazevski, N. (2012). Learning through a reflection: Becoming an effective PhD supervisor. International Journal of Learning and Development, 2(5), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C., Kadiwal, L., Telling, K., Ashall, W., Kirby, J., & Mwale, S. (2022). restorying imposter syndrome in the early career stage: Reflections, recognitions and resistance. In The palgrave handbook of imposter syndrome in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R., & Mifsud, N. (2019). Structural inequality in higher education: Creating institutional cultures that enable all students (p. 67). La Trobe University. Available online: http://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NaylorMifsud-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Orsini, J. (2023). Mentoring and well-being in higher education. Journal of Leadership Studies, 17(3), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, M., & Noyes, S. (2017). Reflective boot camp: Adapting LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® in higher education. Reflective Practice, 18(2), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, M., & Turesky, F. E. (2018). Shared leadership lessons: Adapting LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® in higher education. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 5(4), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. C. (1995). The good, the bad, and the ugly: The many faces of constructivism. Educational Researcher, 24(7), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D., & Stupans, I. (2012). Exploring the potential of role play in higher education: Development of a typology and teacher guidelines. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(4), 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, C. (2015). Promoting playfulness in publicly initiated scientific research: For and beyond times of crisis. International Journal of Play, 4(3), 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, D., Mostert, E., & Wolters, H. A. (2005). Learning together to practice together. In D. Ridder, E. Mostert, & H. A. Wolters (Eds.), Harmonising collaborative planning. University of Osnabrück, Institute of Environmental Systems Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, L., & Stephenson, M. (2008). Charting the challenges and paradoxes of constructivism: A view from professional education. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(5), 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, C., & Taitz, M. (2012). Who “owns” the university? Institutional autonomy and academic freedom in an age of knowledge capitalism. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10(2), 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, R., Dimitrova, R., Pourgoura, A., Roberts, S., & West, S. (2020). Building knowledge and learning communities using LEGO° in nursing. In K. Gravett, N. Yakovchuk, & I. M. Kinchin (Eds.), Enhancing student-centred teaching in higher education: The landscape of student-staff research partnerships. Palmgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D., Antón-Sancho, Á., & Fernández-Arias, P. (2023). Player profiles for game-based applications in engineering education. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 31(1), 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A. (2023). Lego® Serious Play® and higher education: Encouraging creative learning in the academic library. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).