Abstract

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may face significant challenges in general education settings, particularly in the absence of support from skilled teachers. One of the most frequently reported challenges in the literature involves difficulties in the social domain, specifically in peer interactions. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the efficacy of a behavior analytic intervention in improving the social skills of three preschoolers with ASD during recess. The efficacy of the treatment, which included prompting, social reinforcement, and self-management procedures, was assessed using a multiple-baseline across-participants experimental design. Results demonstrated that the intervention was effective in promoting appropriate social behavior of the three preschoolers with ASD, whereas self-management strategies contributed to further improvement and maintenance of the treatment outcomes even in the absence of support from a shadow teacher.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education has emerged as a cornerstone of educational reform in many countries, aiming to make education accessible to all students with disabilities and offer them opportunities for equal participation and educational benefits across all levels of education (Kefallinou et al., 2020). Despite the progress achieved in inclusive education in terms of legislation, leadership, and practices, numerous challenges remain and need to be addressed, which leads to controversies among researchers, practitioners, and government officials. One of the primary controversies is whether it is necessary to provide specialized interventions and practices according to the individual needs of each student with a disability; in other words, whether inclusive education practices are sufficient to ameliorate the outstanding difficulties of students with disabilities and therefore lead to the discontinuation of all types of specialized interventions (Kauffman et al., 2022). While the ethical, therapeutic, and educational benefits of inclusive education are well established, the need for specialized services and interventions cannot be overlooked to effectively meet the needs of each group of students with the same diagnosis and even of each individual student since there is great heterogeneity in the phenotypes of each diagnostic categorization (Kauffman et al., 2023). The current study aims to highlight the importance of evidence-based interventions as a means of facilitating decision making regarding students with special educational needs, with an emphasis on students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The specific population was selected because an ever-growing number of children with ASD are included in general educational settings (Snyder et al., 2019). Nevertheless, preschool and school-age children with ASD, even those with IQ scores within or above average, are less engaged in peer interactions and demonstrate great difficulties in initiating interactions and in responding to the social invitations of their peers (Locke et al., 2016). Those difficulties impede their ability to establish relationships with peers and to adjust to school demands (Camargo et al., 2015).

There is a great challenge in teaching students with ASD to engage socially in a school setting for several reasons, including impaired social cognition and difficulties in recruiting social reinforcement and in achieving emotional regulation (Chevallier et al., 2012; Southall & Gast, 2011). Thus, systematic intervention efforts that promote social engagement, especially during recess, are important for the well-being of children with ASD in schools, as participation in social activities in this context offers numerous developmental and educational benefits (Gilmore et al., 2019; Lang et al., 2011; Locke et al., 2016). Additionally, recess provides valuable opportunities to teach and practice social skills, which are likely to generalize and be maintained as they come under natural contingencies of reinforcement (Bellini et al., 2007). There are a great number of behavior analytic studies that have successfully addressed those skills (Camargo et al., 2015). For example, there are studies that adopt adult-mediated procedures, such as prompting and reinforcement contingencies (e.g., Gena, 2006; Hustyi et al., 2023), incidental teaching (Blackwell & Stockall, 2021), and script-fading procedures (Wichnick-Gillis et al., 2019), which were found to be highly effective in this domain.

Despite their efficacy, adult-mediated procedures may also have disadvantages, such as being intrusive or leading to over-dependency on prompting procedures (Kasari et al., 2011). To address those shortcomings, self-mediated procedures have also been employed. Self-management, defined as “the personal application of behavior change tactics that produces a desirable improvement in behavior” (Cooper et al., 2020, p. 736), has been shown to be effective in promoting independent functioning in inclusive settings (e.g., Agran et al., 2005; Reinecke et al., 2018) and in the acquisition, generalization, and maintenance of social skills (e.g., Cohen et al., 2022; Hume et al., 2021; Koegel et al., 2014). Such outcomes lead us to consider self-management procedures, such as self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-administered consequences, to be highly appropriate and effective in promoting social competence in children with ASD (Davis et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2007).

A literature review on self-management and ASD led to five studies that employed self-management procedures to improve the social skills of children with ASD in inclusive educational settings, and they all employed self-monitoring procedures in combination with prompting procedures and reinforcement contingencies (Apple et al., 2005; Loftin et al., 2007; Morrison et al., 2001; Shearer et al., 1996; Strain et al., 1994). Nevertheless, apart from one study (Loftin et al., 2007), the conditions under which training occurred was rather contrived (e.g., in pull-out classrooms with trained peers). In the Loftin et al. study, however, the social improvement of children with ASD was noted during lunchtime.

Due to the paucity of research in the area of ASD in Greece, in conjunction with some important issues that arise from the literature regarding the efficacy of behavior analytic technology in addressing the social interaction difficulties of preschoolers with ASD, this study aimed to identify procedures that promote and maintain independent social functioning during free-play activities during recess. Specifically, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of a multi-component behavior analytic intervention that incorporates antecedent strategies (e.g., prompting procedures), reinforcement contingencies (e.g., social reinforcement contingencies), and self-management procedures in fostering and maintaining independent interactions with peers. To address these objectives, the following research questions were formulated:

Research Question 1. does a treatment package combining adult-mediated and self-management procedures increase the frequency of independent initiations for interaction and replies to peer initiations among three preschoolers with ASD in an inclusive school setting during recess?

Research Question 2. do self-management procedures reduce the need for guidance and reinforcement provided by shadow teachers, and do the treatment outcomes maintain in the absence of adult-mediated interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample of the present study was a convenient sample and consisted of three preschoolers with ASD who were recruited from a non-profit day-treatment center located in Greece specializing in early intensive behavior analytic intervention, which they attended after school. The criteria for participation were as follows: (a) a formal diagnosis of ASD, (b) within the age range of 4–6 years, (c) typical intellectual functioning, (d) ability to communicate verbally, (e) absence of severe behavioral problems, (f) enrollment in a general education preschool, (g) difficulties in interacting with peers, and (h) receiving behavior analytic treatment. Those criteria were verified by formal assessments and by the clinical teams responsible for the participants. The participants’ diagnoses were given by independent agents working in public health settings and were based on ICD-11 and DSM-5 criteria.

The three 4-year-old preschoolers who were selected were given the pseudonyms Keith, Bob, and Gregory. They all lived in an urban area with their families and had acquired basic expressive and receptive language skills, imitation skills, and had mild behavioral difficulties. Their intellectual functioning was considered to be at age-appropriate levels as assessed by independent professionals working in public health settings. Nevertheless, they were all isolated from their peers at school and engaged mostly in solitary activities during free-play activities. They did not respond to their classmates’ social invitations nor did they initiate such interactions. In addition, Bob and Gregory were highly dependent on their shadow teachers’ assistance. Participants’ scores, characteristics, and hours of intervention are summarized in Table 1. The participants’ parents signed a consent form after they were informed about the purposes and the procedures of this research effort.

Table 1.

Participants’ chronological age, scores, and therapeutic intervention.

2.2. Settings and Therapists

This study was conducted in the three preschools where the participants were enrolled. Data were collected in the schoolyard during recess. The schedule was held as usual, and no special arrangements were made for the purposes of this study. In the schoolyard, there were 20–40 children at all times, supervised by one to two teachers, who did not interfere or instruct the children during their play activities. Sandpits, slides, seesaws, and other outdoor game activities were available.

Three therapists, with a degree either in psychology or education and highly experienced in the use of behavior analytic intervention for children with ASD, were hired by the participants’ parents to serve as shadow teachers in the general education school settings. They provided support to the participants throughout the school day and implemented the intervention during recess. Prior to the intervention, the shadow teachers received training that included familiarization with the intervention procedures used in the study (i.e., prompting, social reinforcement, and self-management) and the data collection methods. The training of the therapists in data collection procedures was conducted by the first researcher and consisted of two brief sessions of approximately 30 min each. A mastery criterion of 80% was set for procedural fidelity.

2.3. Response Definitions for the Dependent Variables

For the purposes of the present study, the functional definitions of the dependent measures of the Gena (2006) study were used with minor adaptations. Independent initiations for interaction with peers were defined by the statements that the participants made toward classmates. They had to (a) include socially appropriate language, (b) be contextually relevant, (c) be articulated clearly and loudly so that peers could hear and comprehend them, and (d) be articulated independently, without the shadow teacher’s help, and in the absence of disruptive or stereotypic behavior.

The types of initiations taught belonged to the following response categories: (a) asking questions, (b) showing affect, (c) giving commands, (d) announcing information, (e) inviting classmates, and other types of socially appropriate social initiations (e.g., giving compliments). Those categories were identified as the most frequently used during interactions of typically developing preschoolers (Gena & Kymissis, 2001).

Independent replies were defined by the verbal and nonverbal responses to peers’ initiations for interaction (e.g., the child with ASD followed his classmate after the latter’s invitation to play together). Replies were defined by the same criteria as initiations.

2.4. Experimental Design and Procedure

A concurrent multiple-baseline across-participants design was used to assess the efficacy of the intervention (Gast et al., 2018). The experimental phases included a baseline, two intervention phases, and a follow-up condition. The baseline and the first intervention condition closely followed those applied in the Gena (2006) study.

Baseline. During baseline, the shadow teacher gave the instruction “you can play now” and provided no other instruction, assistance, or reinforcement contingent on the dependent variables of this study or related to the child’s play. Nevertheless, the shadow teacher remained within 6-feet proximity to the child and did not interact with him unless he addressed her or to interrupt his inappropriate behavior. When a minimum of 3 sessions were completed and stable responding was obtained, treatment was introduced for the first participant, while continuing to collect baseline data for the other two participants. Upon reaching improved responding, as estimated by visual inspection, treatment was introduced for the second and then for the third participant.

Prompting and Social Reinforcement. As in baseline, the initial treatment condition began with the shadow teacher informing the child with ASD that it was time to play. During this experimental condition, the shadow teacher provided prompting and social reinforcement to increase the frequency of occurrences of the target responses.

Prompting procedures included verbal prompting, verbal modeling, and physical guidance (e.g., a light touch on the participant’s shoulder as a reminder to respond to a peer’s initiation). For example, the shadow teacher would prompt a participant to address a classmate with statements, e.g., “Would you like to play hide and seek?” or “Look what I drew!” The number of prompts provided during half-hour sessions ranged between 20 and 30 to approximate the number of initiations emitted by typically developing peers (Gena & Kymissis, 2001). For replies, a full prompt was provided if a participant did not respond 3 sec after his classmate’s initiation. Since the shadow teachers were highly skilled, they were not given any further instruction regarding the criteria for providing prompts. Social reinforcement was provided contingently upon independent social initiations and replies to peer initiations using a continuous schedule of reinforcement. Social reinforcement included praise and physical contact (e.g., a pat on the back).

Self-management. During the second treatment phase, the participants were trained to self-monitor and self-evaluate their interactions with peers, and to recruit contingent social reinforcement from their shadow teacher. The combination of those procedures was used to promote optimal levels of independent social functioning. As in the previous condition, the shadow teacher delivered prompting and social reinforcement contingencies to increase the frequency of target responses. Following implementation of the self-management strategies, prompting was gradually faded out and the schedule of reinforcement, which was initially continuous, was gradually thinned out to fixed-ratio schedules ranging from 10 to 15 responses per reinforcement delivery.

The participants were trained to identify and record their own social initiations and replies toward their typically developing peers in the context of free-play activities. The self-monitoring part of their training was based on the training manual of Koegel et al. (1992). Specifically, two days prior to the second treatment phase, the participants were taught to discriminate between occurrences and non-occurrences of initiations and replies. The shadow teachers explained what “talking to peers” means and then asked “Are you talking to your peers?” during both prompted and unprompted interactions with peers. The child’s answer was followed by the shadow teacher’s feedback—either corrective or praise contingent upon the child’s accurate discriminations. The training criterion was set at 80% accuracy. Participants acquired the discrimination skills within three 30 min training sessions conducted on 2 consecutive days.

After completion of the discrimination training, the second phase of the intervention, the self-management phase, began. The participants were trained (through verbal prompting, modeling, and physical guidance) to self-monitor the target responses. Specifically, they learned to track down their responses by using a small hand counter hung by a hoop on their trousers. A light press on the hand counter—which the participants were able to make without diverting their attention from activities or drawing their classmates’ attention—was sufficient for tracking the cumulative number of their initiations and replies. Social reinforcement was used contingently upon correct recordings of the participants. If they exhibited the appropriate behavior without recording it, the shadow teacher would praise for appropriate social behavior but would also remind them to self-monitor. In addition, the participants were taught (through verbal prompting, physical guidance, and social reinforcement procedures) to self-evaluate their performance and recruit social reinforcement from the shadow teacher when they had earned enough points. Instead of verbally reminding the participants of the criteria for receiving reinforcement, the shadow teacher wrote on the child’s hand, at the beginning of each session, how many points he needed to earn. In addition, they were taught to check their counters during their interaction with their peers and compare the number on the counter with the cue written on their hand, and to approach the shadow teacher when they earned the due number of points and say to her “look” or “I earned… (number of points)”. After the participants’ behavior was reinforced, their counter was reset, and they started self-monitoring their interactions all over.

All prompts and reinforcers provided for self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and recruiting reinforcement were systematically faded out apart from the visual prompt for self-evaluation. Specifically, when the participants were able to record accurately and independently 80% of their social interactions, prompting and reinforcement were no longer provided for self-monitoring, whereas, for recruiting reinforcement, the training criterion was set at 100%. Within 6, 3, and 4 sessions, Keith, Bob, and Gregory, respectively, acquired the targeted self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and recruiting reinforcement skills.

Follow-up. Following completion of the intervention phases, a 3-month follow-up session was conducted. The same procedure as in baseline was implemented during follow-up sessions. During follow-up, no training was provided and the hand counter for self-management was not available. In addition, for Bob, a second follow-up session was conducted a year after the completion of the intervention.

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected once or twice per week. For Keith, the duration of baseline and intervention was 3 months, whereas for Bob and for Gregory it was 6 and 9 months, respectively. The long duration of the intervention in the case of Gregory was partly attributed to a period of a one-month interruption of this study due to a temporary departure of his family from their hometown, the location where the research was conducted. Sessions began at the starting point of free-play activities and had a 30 min duration.

Occurrences of initiations were recorded by drawing tally marks in the boxes that corresponded to each response category (questions, commands, etc.). The sum of initiations per 30 min sessions added to one data point. Occurrences of replies were recorded by scoring a “+” sign and a “−” sign for non-occurrences. A reply was expected for all opportunities for interaction attempted by classmates, whether verbal or nonverbal, that aimed to engage the participants in social interaction. The percentage of replies to classmates’ initiations was calculated by dividing the number of replies by 5—for every 5 opportunities for interaction provided by classmates—and multiplying that quotient by 100.

Regarding self-monitoring accuracy, recordings were considered accurate when the participants scored an initiation or reply when they occurred and inaccurate when either scored in the absence of a communication attempt or when the participant failed to record the occurrence of an initiation or reply. The percentage of self-monitoring accuracy was calculated by dividing the child’s number of correct recordings by the total number of self-monitoring opportunities (i.e., total number of initiations and responses) and multiplying that quotient by 100.

2.6. Inter-Observer Agreement

The first author served as the primary observer and the shadow teachers served as secondary observers for inter-observer reliability purposes. Inter-observer agreement (IOA) was calculated using the total count IOA method (Cooper et al., 2020) on at least 33% of the sessions for each participant and for all experimental conditions. Specifically, the smaller number of initiations, recorded by one observer, was divided by the larger number of initiations or replies recorded by the second observer and the quotient was multiplied by 100. The same procedure was followed to calculate inter-observer agreement for replies, frequency of prompting, and self-monitoring accuracy. For privacy reasons, video recording of the sessions was prohibited and therefore trial-by-trial IOA calculations could not be obtained.

Inter-observer agreement across all observations ranged from 80 to 100%, with an average of 95% agreement. Specifically, the percentage of agreement for initiations of interaction with peers averaged at 92% (range: 82–100%), whereas, for replies, the average was 96% (range: 80–100%), for self-monitoring 95% (range: 90–100%), and for prompts 98% (range: 94–100%).

2.7. Procedural Fidelity

A 25-item (e.g., no more than 30 prompts were delivered, the child was wearing his hand counter, social reinforcement was delivered contingently) checklist was constructed for the purposes of the present study to secure procedural integrity. Fidelity was assessed in 50% of the sessions across all conditions and for each participant and it was calculated by dividing the number of items completed accurately by the total number of items. Overall fidelity averaged at 98%, with a range of 95% to 100%.

2.8. Social Validity

Το ensure that the targeted responses were socially valid, parents and preschool teachers were asked to evaluate the most outstanding needs of their children with ASD in inclusive settings. In addition, the target responses were drawn from a normative data study pertaining to the social responding of preschoolers conducted in the same geographical area as the present research (Gena & Kymissis, 2001).

Furthermore, the social validity of the outcome of the intervention was assessed using normative data and specifically by comparing the average performance on target responses of each participant with the performance of typically developing peers as they were depicted in the study of Gena and Kymissis (2001). Finally, the three preschool teachers of the participants answered four open-ended questions, regarding the importance of changes noted in each of the participants’ social behavior following intervention (e.g., “Did you notice any changes in ___ (name of the participant)’s behavior since we started our program?” “Do you attribute any of those changes to the intervention?”).

2.9. Data Analysis

To evaluate the efficacy of the intervention, both visual and statistical analyses were used. Level of responding, trend, variability, immediacy, overlap, and consistency were taken into consideration for the purposes of visual analysis (Barton et al., 2018). The statistical analysis included the calculation of the Tau-U index, which is an overlap metric assessing the degree of non-overlapping data between adjacent conditions (Parker et al., 2011). In addition, it is often used to calculate effect sizes of interventions (e.g., Wolfe et al., 2019) (Tau-U ≤ 0.31 = minimal effect, range of 0.32–0.84 = moderate effect, Tau-U > 0.85 = strong effect; Parker & Vannest, 2009). For the purposes of the current study, the data from both intervention phases were collapsed and compared with baseline data using the online calculator developed by Vannest and colleagues (Vannest et al., 2016). Tau-U was calculated separately for each tier of the multiple baselines and for the total number of initiations and replies.

3. Results

3.1. Initiations for Interaction

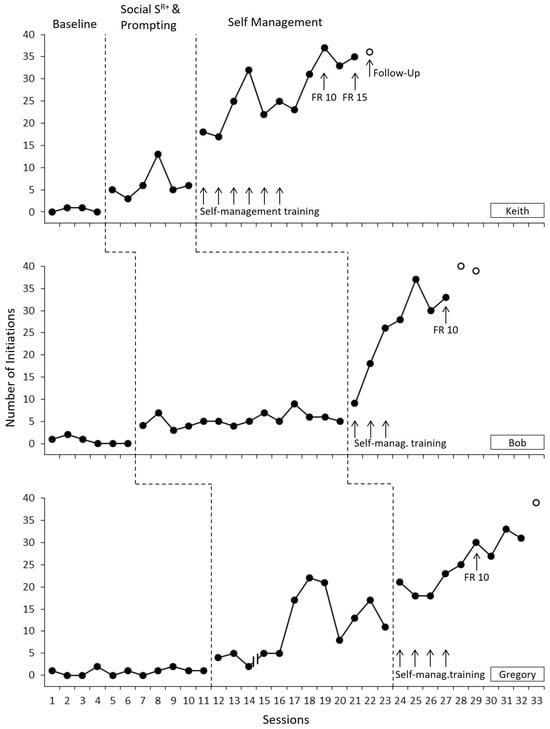

Figure 1 depicts the number of independent initiations emitted by children with ASD toward their peers. The open circles depict the follow-up data. The arrows indicate the sessions in which self-management training was provided and the point at which the reinforcement schedule was thinned to the lowest level of the fixed ratio (10 or 15 responses per reinforcement delivery). The parallel vertical lines on Gregory’s graph indicate the point at which data collection was interrupted for technical reasons.

Figure 1.

Number of independent initiations of three children with ASD per session.

Throughout baseline, the participants made a very small number of initiations toward their peers, close to zero levels. Their performance was stable with no trend or variability. As visual analysis revealed, an immediate change in level and trend occurred only when the intervention was introduced for each participant, with no changes in the baseline data in the other tiers. Following the implementation of self-management strategies, the frequency of initiations increased further, along with the data trend. Changes in performance were consistent across the three demonstrations of effect, and statistical analysis indicated a significant increase in initiations (Tau-U = 0.99, 90% CI [0.73, 1]), indicative of a highly effective intervention.

During baseline, Keith emitted 0–1 initiations per 30 min sessions. During the initial treatment phase—the social reinforcement and prompting condition—there was an immediate increase (M = 6, range = 3–13) in the frequency and trend of the initiations. During the second treatment phase—the self-management condition—Keith’s initiations increased dramatically to an average of 27 per 30΄ (range = 17–37). In the 3-month follow-up session, Keith emitted 36 independent initiations for interaction with peers per session. Differences between baseline and the two intervention phases resulted in a Tau-U score of 1.00 (90% CI [0.46, 1]), indicating a strong effect size. During baseline Bob emitted 0–2 initiations. With the introduction of the initial intervention, there was an immediate change in the level of the data, in the desired direction, with no overlap with baseline (M = 5, range = 3–9). The frequency of the initiations increased further after the implementation of the self-management phase (M = 26, range = 9–37) accompanied by increases in the trend. At the 3-month and 1-year follow-up sessions, Bob emitted 40 and 39 initiations, respectively. The Tau-U score for the second participant was 1.00 (90% CI [0.55, 1]), indicating a strong effect of the intervention. Gregory made 0–2 initiations to peers during the 11 sessions of the baseline condition. Upon the introduction of the initial treatment phase, a slight increase in level occurred with minimal overlap (1 data point) during the first five sessions, followed by a large increase in level and trend during the next sessions. The average of initiations to peers during the first treatment phase was 11 (range = 2–22). Gregory’s initiations to peers continued to increase following the introduction of the second treatment phase (M = 25, range = 18–33). Gregory’s initiations increased to 39 during the 3-month follow-up session. His Tau-U score was 0.99 (90% CI [0.63, 1]). Variability in the type of initiations was also noted. Specifically, 28% of the initiations were announcements, 25% asking questions, 24% giving commands, 2% affective expressions, and so on.

3.2. Replies to Peers’ Initiations for Interaction

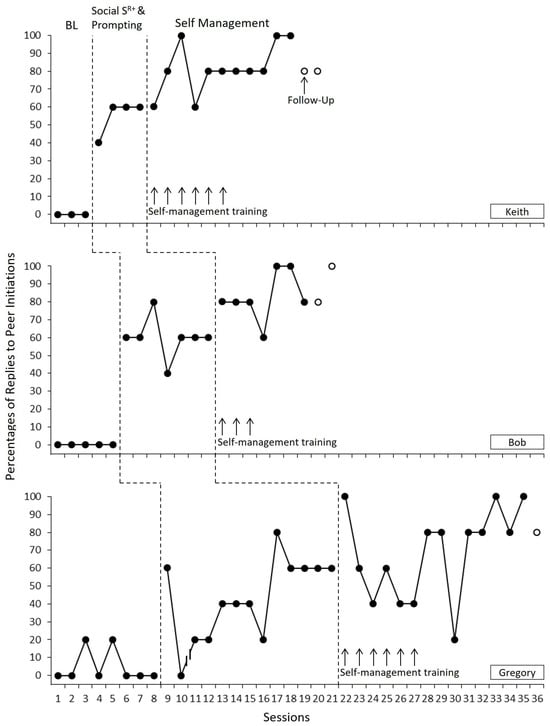

Figure 2 depicts the percentages of the participants’ independent replies to their peers’ initiations for social interaction. Each data point reflects the percentage of independent replies per five invitations for social interaction (the same figure captions were used as for the initiation data).

Figure 2.

Percentages of independent replies of three children with ASD per session.

Throughout baseline, the participants replied to 0–20% of their peers’ initiations. As in the case of initiations, intervention was introduced for each participant when a clear increase in the data of the previous participant was noted. An immediate increase in level occurred following the initiation of the intervention for all three participants. The statistical analyses revealed a significant increase in replies, with a Tau-U score of 0.96 (90% CI [0.67, 1]) across the three participants.

During baseline, Keith and Bob did not reply to any of their peers’ initiations for interaction, whereas Gregory responded to an average of 5% (range = 0–20%) of his peers’ initiations, with a slight downward trend in his performance. With the introduction of intervention, there was an immediate and high increase in all three participants’ replies. Specifically, during the initial treatment phase, Keith replied to his classmates’ initiations with an average of 55% per five opportunities (range = 40–60%). Following the introduction of self-management procedures, Keith’s replies averaged at 82% (range = 60–100%). Replies were maintained at 80% during the 3-month follow-up session. Keith had a Tau-U score of 1.00 (90% CI [0.38, 1]). Bob demonstrated an immediate increase in the level of independent replies after the introduction of the first treatment phase (M = 60%, range = 40–80%), which increased to 83% on average (range = 60–100%) during the second treatment phase. Furthermore, during the 3-month and 1-year follow-up sessions, Bob replied an average of 80% and 100%, respectively. The Tau-U score for the second participant was 1.00 (90% CI [0.49, 1]). Greater variability was noted in Gregory’s performance. During the first treatment phase, there was an immediate change in levels in the first session, followed by a decline in his performance. Although there was a minimal overlap with baseline (4 data points out of 13), the average was well above the baseline level (M = 43, range = 0–80%). After the implementation of the self-management procedures, his replies averaged 69% (range = 20–100%). During the 3-month follow-up session, his independent replies were at 80%. Gregory’s Tau-U score was 0.91 (90% CI [53, 1]), which corresponds to a strong effect size.

3.3. Frequency of Prompting

During the initial treatment phase, 22 prompts, on average, were provided per session for Keith (range: 20–25), 26 for Bob (range: 22–30), and 25 for Gregory (range: 22–30); during the self-management phase, 3 prompts, on average, were provided per session for Keith (range: 0–10), 7 for Bob (range: 0–22), and 5 for Gregory (range: 0–15). Nevertheless, shadow teachers’ prompts gradually faded within four to six sessions following implementation of the self-management procedures. No prompts were provided during the last three sessions of the second treatment phase.

3.4. Self-Monitoring Accuracy

The accuracy with which the children with ASD independently self-monitored their interactions with peers averaged 76% and ranged from 72% for Gregory to 83% for Keith. Most errors were attributed to failure to record interactions that occurred. “Cheating” (recording interactions that had not occurred) happened only twice throughout this study.

3.5. Social Validation of the Results

Based on the preschool teachers’ responses to the open-ended questions, the intervention was highly effective. Specifically, all three preschool teachers considered the intervention to be effective, reporting rapid improvements in social interactive skills of the participants, which resulted in age-appropriate levels of social behavior during free-play activities. In addition, they reported a shift in their expectations from children with ASD. Namely, they started to realize that improvement was possible for their students with ASD, and, in fact, they expressed an interest in receiving training to learn to implement the treatment procedures themselves.

The comparison between the average performances on target responses of each participant with those of typically developing peers (Gena & Kymissis, 2001) showed that, although, during baseline, the participants’ performances were below the range of normative data, during the treatment conditions, both initiations and reply statements increased to the point of reaching that range. The only exception was Gregory’s replies, which continued to be below average. In addition, during the self-management condition, the average of Keith and Bob’s initiations and the average of Keith’s replies were even higher than the average performance of their peers.

4. Discussion

The present study has demonstrated that a combination of behavior analytic procedures was effective in producing improved outcomes in the social skills of preschoolers with ASD during interactions with their peers at school. Specifically, a combination of reinforcement and prompting procedures was effective in increasing the frequency of the participants’ independent initiations for interaction and their replies to peers’ initiations, aligning with findings from the Gena (2006) study. Most importantly, it was demonstrated that, for students with ASD, self-management skills, such as self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and recruiting reinforcement for oneself, may be effective in enhancing the social skills of preschoolers with ASD and in maintaining those skills over time under the most challenging conditions for a child with ASD—the unstructured setting of free-play activities in preschool—and in the absence of teaching assistance.

Even though several studies have addressed the social behavior of children with ASD in inclusive settings, the present study is innovative in several ways as follows: (a) Classmates were naive to the purposes of this study and did not receive training aiming to facilitate treatment outcomes. (b) A wide range of social responses were targeted (e.g., asking questions, giving commands, announcing information), in contrast to prior self-management studies that addressed a limited number of social responses (e.g., Loftin et al., 2007). (c) Data were collected for a much longer period (3 to 9 months), and maintenance of the acquired responses was assessed at a much later point in time (up to one-year follow-up for one of the participants). (d) Social reinforcement contingencies were used, rather than primary reinforcers, as in prior self-management studies. (e) A self-evaluation and self-recruiting reinforcement strategy was introduced as a means of increasing the social behavior of preschoolers with ASD in inclusive educational settings. Although this strategy is identified as being important for the purposes of inclusion (Alber & Heward, 2000), its effectiveness has not been empirically investigated in schools, as our review of the literature revealed. (f) The social validity of the present study was evaluated in several ways, including the use of normative data for the selection of response categories and the evaluation of the treatment effects, unlike most self-management studies (e.g., McDougall et al., 2017).

Self-management procedures contributed to an increase in social interaction skills, which the participants had acquired through direct instruction (prompting and reinforcement procedures). This finding is in agreement with prior research findings (e.g., Loftin et al., 2007) and in alignment with the theoretical framework of self-management from a behavior analytic perspective (Gena et al., 2014). For children with ASD, interactions with peers per se may not have reinforcing properties. Self-monitoring and other self-management procedures function as mediators between the target behavior and both weak (e.g., peer replies to participant’s initiation) and delayed (e.g., reinforcement provided by the shadow teacher after a predetermined number of initiations have occurred) reinforcing contingencies, which would probably not be sufficient to exert control over the social behavior of children with ASD in the absence of this mediation (Baer, 1984).

Maintenance of the treatment outcomes was obtained and may be attributed to two parameters: (a) the follow-up was conducted in the same setting as the intervention since it was a naturalistic setting (the participants’ schools) and (b) the length of the treatment phases that may have resulted in over-training. A possible interpretation of this finding would be that participants with ASD continued covertly to self-manage their social behavior (Stokes & Osnes, 1986) or that covert rules governed their behavior (Malott, 1984). Finally, it is possible that the newly acquired social responses came under the control of natural contingencies of reinforcement, which also led to the high maintenance of those responses, as has been the case in prior research addressing social behavior (Briesch et al., 2018).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Nevertheless, the aforementioned interpretations about what parameters may govern self-management and social-engagement skills cannot be confirmed since they were beyond the scope of the present study, but they are certainly worth investigating in future research. A limitation of the present study was the unavoidable interruption of the data collection procedure for one month for the third participant (Gregory) due to the temporary relocation of his family. A further point of concern was the physical presence of the researcher during the follow-up condition, which may have led to inadvertently cuing the targeted social behavior. It would be preferable if the follow-up data were collected by an independent observer naive to the purposes of the study and unfamiliar to the participants. Additionally, since video recording was not permitted in the school settings, it was not possible to assess the reliability of the procedural fidelity data and apply more stringent criteria to assess the reliability of the data collection process, such as calculating the trial-by-trial agreement using the time stamps. The present study concentrated on quantitative characteristics of the participants’ social behavior (number of initiations and replies). In the future, it would be interesting to explore both quantitative and qualitative aspects of social interactions between children with ASD and their peers. This could include factors such as the appropriateness of their effects during interactions, whether they engaged with multiple peers or just a few, the quality and duration of their conversations (e.g., length of utterances, number of exchanges in dialogues), and the generalization of acquired social skills to different school settings, such as instructional periods or group activities in the classroom. Furthermore, future studies could also examine the extent to which these social skills generalize to non-school environments, such as the home or community settings, to better understand the broader impact and sustainability of the intervention.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated a functional relationship between behavior analytic teaching procedures and the social skills of three preschool children with ASD in inclusive educational settings, specifically during recess. These procedures appeared to enhance the children’s ability to interact with peers and facilitated their adaptation to the school environment, as engaging in play and social interactions with classmates during recess is a fundamental aspect of their school experience, contributing to their physical, cognitive, and social development.

The effectiveness of these methods suggests that shadow teachers may consider implementing behavior analytic approaches to promote social engagement and autonomy in children with ASD in general education settings, provided they are trained to implement them with fidelity. Specifically, strategies such as prompting, social reinforcement, and self-management may be employed to support social skill development across various school contexts that provide ample opportunities for peer interaction, including classroom instruction, group activities, free play, lunchtime interactions, field trips, team sports, and leisure activities.

Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size and the individualized shadow-based nature of this intervention. There is only one prior study that followed the same methodology applied with equal success, which also involved a small number of children with ASD (Gena, 2006). Further research involving larger and more diverse samples of children with ASD, and studies in which school teachers serve as the primary implementers of the intervention, is necessary to assess the generalizability and practical feasibility of these strategies when applied in general education classroom settings without one-on-one support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and A.G.; methodology, P.G. and A.G.; validation, P.G. and A.G.; formal analysis, P.G.; investigation, P.G. and A.G.; resources, P.G. and A.G.; data curation, P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, P.G. and A.G.; visualization, P.G.; supervision, P.G. and A.G.; project administration, P.G. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of INSTITUTE OF SYSTEMIC BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS-ISAS (protocol code: 2090, approval date: 29 June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants included in the study, as well as from the parents of the minors who participated in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agran, M., Sinclair, T., Alper, S., Cavin, M., Wehmeyer, M., & Hughes, C. (2005). Using self-monitoring to increase following-direction skills of students with moderate to severe disabilities in general education. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40(1), 3–13. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879767 (accessed on 10 June 2010).

- Alber, S. R., & Heward, W. L. (2000). Teaching students to recruit positive attention: A review and recommendations. Journal of Behavioral Education, 10(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apple, A. L., Billingsley, F., Schwartz, I. S., & Carr, E. G. (2005). Effects of video modeling alone and with self-management on compliment-giving behaviors of children with high-functioning ASD. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D. M. (1984). Does research on self-control need more control? Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 4(2), 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, E. E., Lloyd, B. P., Spriggs, A. D., & Gast, D. L. (2018). Visual analysis of graphic data. In J. R. Ledford, & D. L. Gast (Eds.), Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (3rd ed., pp. 179–214). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L., & Hopf, A. (2007). A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28(3), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, W., & Stockall, N. (2021). Incidental teaching of conversational skills for students with autism spectrum disorder. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 54(2), 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A. M., Daniels, B., & Beneville, M. (2018). Unpacking the term “self-management”: Understanding intervention applications within the school-based literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, S. P. H., Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Hong, E. R., Davis, H., & Mason, R. (2015). Behaviorally based interventions for teaching social interaction skills to children with ASD in inclusive settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education, 25(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, C., Kohls, G., Troiani, V., Brodkin, E. S., & Schultz, R. T. (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Koegel, R., Koegel, L. K., Engstrom, E., Young, K., & Quach, A. (2022). Using self-management and visual cues to improve responses to nonverbal social cues in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification, 46(3), 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2020). Applied Behavior Analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. L., Mason, B. A., Davis, H. S., Mason, R. A., & Crutchfield, S. A. (2016). Self-monitoring interventions for students with ASD: A meta-analysis of school-based research. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, D. L., Lloyd, B. P., & Ledford, J. R. (2018). Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In J. R. Ledford, & D. L. Gast (Eds.), Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (3rd ed., pp. 239–281). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gena, A. (2006). The effects of prompting and social reinforcement on establishing social interactions with peers during the inclusion of four children with autism in preschool. International Journal of Psychology, 41(6), 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gena, A., & Kymissis, E. (2001). Assessing and setting goals for the attending and communicative behavior of three preschoolers with autism in inclusive kindergarten settings. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 13(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gena, A., Galanis, P., & Ala’i-Rosales, S. (2014). Self-management from a behavior analytic standpoint: Theoretical advancements and applications in autism spectrum disorder. Hellenic Journal of Cognitive Behavior Research and Therapy, 1(1), 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, S., Frederick, L. K., Santillan, L., & Locke, J. (2019). The games they play: Observations of children with autism spectrum disorder on the school playground. Autism, 23(6), 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K., Steinbrenner, J. R., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2021). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: Third generation review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(11), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustyi, K. M., Ryan, A. H., & Hall, S. S. (2023). A scoping review of behavioral interventions for promoting social gaze in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 100, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2011). Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J. M., Ahrbeck, B., Anastasiou, D., Felder, M., Hornby, G., & Lopes, J. (2023). The Unintended consequences of the full inclusion movement. Global Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 11(4), 555819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J. M., Anastasiou, D., Hornby, G., Lopes, J., Burke, M. D., Felder, M., Ahrbeck, B., & Wiley, A. (2022). Imagining and reimagining the future of special and inclusive education. Education Sciences, 12(12), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefallinou, A., Symeonidou, S., & Meijer, C. J. W. (2020). Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. Prospects, 49(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., & Parks, D. R. (1992). How to teach self-management to people with severe disabilities. A training manual. University of California. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336880 (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Koegel, L. K., Park, M. N., & Koegel, R. L. (2014). Using self-management to improve the reciprocal social conversation of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R., Kuriakose, S., Lyons, G., Mulloy, A., Boutot, A., Britt, C., Caruthers, S., Ortega, L., O’Reilly, M., & Lancioni, G. (2011). Use of school recess time in the education and treatment of children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H., Simpson, R. L., & Shogren, K. A. (2007). Effects and implications of self-management for students with autism: A meta-analysis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(1), 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J., Shih, W., Kretzmann, M., & Kasari, C. (2016). Examining playground engagement between elementary school children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(6), 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftin, R. L., Odom, S. L., & Lantz, J. F. (2007). Social interaction and repetitive motor behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(6), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malott, R. W. (1984). Rule-governed behavior, self-management, and the developmentally disabled: A theoretical analysis. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 4(2), 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, D., Heine, R. C., Wiley, L. A., Sheehey, M. D., Sakanashi, K. K., Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2017). Meta-analysis of behavioral self-management techniques used by students with disabilities in inclusive settings. Behavioral Interventions, 32(4), 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L., Kamps, D., Garcia, J., & Parker, D. (2001). Peer mediation and monitoring strategies to improve initiations and social skills for students with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(4), 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, D. R., Krokowski, A., & Newman, B. (2018). Self-management for building independence: Research and future directions. International Journal of Educational Research, 87, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, D. D., Kohler, F. W., Buchan, K. A., & McCullough, K. M. (1996). Promoting independent interactions between preschoolers with autism and their nondisabled peers: An analysis of self-monitoring. Early Education and Development, 7(3), 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2019). Digest of education statistics 2018 (NCES 2020-009). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020009.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Southall, C., & Gast, D. (2011). Self-management procedures: A comparison across the autism spectrum. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46(2), 155–171. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23879688 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Sparrow, S., Balla, D., & Cicchetti, D. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales. American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, T. F., & Osnes, P. G. (1986). Programming the generalization of children’s social behavior. In P. S. Strain, M. J. Guralnick, & H. M. Walker (Eds.), Children’s social behavior: Development, assessment, and modification (pp. 407–443). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strain, P. S., Kohler, F. W., Storey, K., & Danko, C. D. (1994). Teaching preschoolers with autism to self-monitor their social interactions: An analysis of results in home and school settings. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2(2), 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., Gonen, O., & Adiguzel, T. (2016). Single case research: Web based calculators for SCR analysis. (Version 2.0) [Web-based application]. Available online: https://singlecaseresearch.org/ (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Wichnick-Gillis, A. M., Vener, S. M., & Poulson, C. L. (2019). Script fading for children with autism: Generalization of social initiation skills from school to home. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(2), 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K., Pound, S., McCammon, M. N., Chezan, L. C., & Drasgow, E. (2019). A systematic review of interventions to promote varied social-communication behavior in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Behavior Modification, 43(6), 790–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).