Abstract

The teaching profession is consistently ranked as one of the most stressful occupations worldwide, creating an urgent need for teacher education programmes to prepare highly skilled and reliant educators. Rooted in social cognitive theory, this study aims to explore preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy beliefs and examine its associations with institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. Social self-efficacy describes one’s confidence in one’s ability to engage in interpersonal relationships, and institutional belonging reflects the extent to which one feels valued and accepted within an institution, while ostracism reflects one’s experience of social exclusion. Two hundred and seventy-one preservice teachers from Greece were recruited to participate in this study via convenience sampling. The measures used were the Perceived Social Self-Efficacy scale (PSSE), Institutional Belongness questionnaire (IB), and Workplace Ostracism Scale (WOS). The results of descriptive statistics showed that preservice teachers’ levels of sense of belonging and social self-efficacy were moderate to high, while they experienced low levels of perceived ostracism. The results of regression analyses indicated that institutional belonging positively correlated with social self-efficacy and negatively with perceived ostracism. The mediation analysis results demonstrated that social self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. Collectively, the findings highlight the importance of developing a supportive educational environment that promotes both a sense of belonging and efficacy beliefs. Enhancing these factors could support preservice teachers’ wellbeing and commitment to the profession and inform policies and practices that promote inclusive educational environments.

1. Introduction

Teaching is consistently ranked as one of the most stressful professions in the world. Teachers face daily challenges such as heavy workloads, inadequate support, demanding interpersonal interactions, and challenging student behaviour, all of which can increase their susceptibility to mental health issues, burnout, and professional dissatisfaction (McCallum et al., 2017; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). Teaching is a challenging and stressful job, particularly for preservice teachers and early-career teachers, who often encounter different stressors and dilemmas (Bjorklund et al., 2020; Kyriacou, 2001). The transition from preservice teachers to early-career teachers is also characterised by a range of tasks, such as managing classroom environments, designing and implementing lesson plans, and interacting with students, colleagues, families, and administrators. These challenges can lead to feelings of self-doubt and insecurity, which may even cause some preservice teachers to reconsider their career choice (Nichols et al., 2017).

A key factor that can prevent or mitigate these negative experiences is the concept of self-efficacy (Bjorklund et al., 2020; Meng et al., 2015), particularly social self-efficacy within this study. Rooted in Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy is defined as “beliefs in one’s ability to organise and execute the courses of action necessary to produce given outcomes” (Bandura, 1997, p. 3), emphasising that beliefs in one’s abilities can significantly influence whether an individual persists and succeeds in a task. Over the past few decades, research has highlighted the significant impact of high teacher self-efficacy on various teacher and student outcomes, including increased motivation, resilience, and the development of supportive and inclusive learning environments for students (Bandura, 1997; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Social self-efficacy, another domain of self-efficacy, is especially relevant for teachers, as it describes their confidence in developing and maintaining affective relationships with others, which is important for building a supportive professional network (Vatou et al., 2022, 2024).

While the benefits of high teacher social self-efficacy are well documented, less is known about the factors that contribute to its development, particularly in the early stages of a teacher’s career (De Clercq et al., 2018; Meng et al., 2015). Addressing this gap is essential, especially for preservice teachers whose social self-efficacy is still being formed as they navigate their training environment. Previous research suggests that a strong sense of institutional belonging can enhance social self-efficacy beliefs by developing a supportive community that fosters professional identity and resilience (Bjorklund et al., 2020; Le Cornu, 2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011, 2017). Conversely, experiences of social exclusion or ostracism can undermine social self-efficacy, leading to the feelings of isolation and disengagement (Hou et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021; Williams, 2007). These dynamics highlight the importance of examining the associations between institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism in the context of teacher preparation. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the level of preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy and explore its mediating role in the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Teacher Social Self-Efficacy

According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), self-efficacy influences how individuals approach challenges and tasks, how persistent they are in the face of adversity, and how resilient they are under stress. Self-efficacy is a future-oriented assessment of one’s abilities, focusing not on actual competence but on an individual’s belief in what they can do (Bandura, 1997). Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2017) described teacher efficacy as the “individual teachers’ beliefs in their own ability to plan, organise, and carry out activities necessary to achieve given educational goals” (p. 1059). Similarly, Pajares (1996) argued that efficacy beliefs “help determine how much effort people will expend on activity, how long they will persevere when confronting obstacles, and how resilient they will prove to be in the face of adverse situations—the higher the sense of efficacy, the greater the effort, persistence, and resilience” (p. 544).

Research based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997) has conceptualised social self-efficacy as a key component in determining an individual’s behaviour in a social setting (e.g., Smith & Betz, 2000; Fan et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2015). Social self-efficacy describes an individual’s perceived ability to initiate and maintain interpersonal relationships (Smith & Betz, 2000). Vatou et al. (2022)) defined teachers’ social self-efficacy as “the teacher’s ability to perform specific interactional tasks, and to develop and maintain positive interpersonal relationships” (p. 5).

Social self-efficacy as a key component of effective social skills has a determining role in social relationships and interaction of individuals (Luo et al., 2019; Sheu et al., 2023). Moreover, social self-efficacy has been identified as a significant predictor of various life outcomes in adults, including overall life satisfaction (Luo et al., 2019; Wright & Perrone, 2010), social outcome expectations and progress towards goals (Sheu et al., 2023), lower levels of depression (Niu et al., 2023), and successful social adjustment (De Clercq et al., 2018; Meng et al., 2015). Additionally, teachers with high social self-efficacy are often better able to build positive relationships with students and colleagues, navigate challenging social situations, and seek support when needed (Vatou et al., 2022, 2024). Fostering preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy within a teacher education program may better equip teachers to meet the interpersonal demands of the profession and, in parallel, enhance their potential for long-term career success (Bjorklund et al., 2020).

2.2. Sense of Belonging

A sense of belonging, which is a fundamental human need, has been widely recognised as crucial to the wellbeing and identity formation of individuals (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It arises from the development of relationships with individuals or groups that support feeling connected and accepted. Meanwhile, these relationships contribute to a sense of purpose and meaning in life (Haim-Litevsky et al., 2023; Lambert et al., 2013). As one becomes more integrated within a community, one develops a stronger sense of identity and belonging to that group (Allen et al., 2021).

A large body of research in educational contexts has demonstrated a positive association between a sense of belonging and various academic outcomes, such as increased motivation, engagement, and overall academic performance (Bjorklund, 2019; Lambert et al., 2013). When preservice teachers feel valued, accepted, and connected within their academic institutions, they report high levels of self-esteem, which promotes resilience and persistence in overcoming academic challenges (Bardach et al., 2022; Lambert et al., 2013; Samadieh & Rezaei, 2024). This sense of belonging is particularly important in higher education, where preservice teachers who perceive themselves as an integral part of their institutions are more likely to exhibit proactive behaviours, such as participating in classroom discussions, seeking support, and pursuing academic and personal goals with a sense of purpose (Strayhorn, 2023).

Institutional belonging in teacher education programmes refers to the extent to which preservice teachers feel connected, supported, and valued within their teacher education programmes. This sense of belonging can buffer against feeling of isolation and self-doubt that often arise during the transition into the teaching profession (Samadieh & Rezaei, 2024; Sotardi, 2022). A strong sense of belonging within teacher education programmes can foster an environment where preservice teachers are encouraged to engage in collaborative learning, seek support from peers and mentors, and develop a professional network that supports their growth and development (Ellis et al., 2020; Le Cornu, 2013, 2016).

While a sense of belonging is widely recognised as essential for students, relatively little research has investigated its impact on preservice teachers (Bardach et al., 2022; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2011) found a positive relationship between teachers’ sense of belonging and their job satisfaction as well as a negative association with emotional exhaustion. These findings underscore how feeling connected and valued within a school community can act as a protective factor against burnout. Similarly, other research has linked teachers’ identification with their school—a concept closely related to belonging—with increased self-efficacy (Bardach et al., 2022; Chan et al., 2008). Self-efficacy is further reinforced when teachers feel part of a supportive professional community and receive constructive feedback, recognition, and support, as suggested by Bandura (1997). This is especially important for preservice teachers. Research has shown that new teachers who feel supported by their peers and mentors are better equipped to handle the challenges of teaching and are less likely to experience isolation and job dissatisfaction (McCallum et al., 2017; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). Therefore, enhancing a sense of belonging for preservice teachers, both in their teacher preparation programmes and eventual school placements, is essential for the development of their efficacy beliefs.

2.3. Ostracism

Ostracism, i.e., social exclusion, is the experience of being ignored or excluded by others (Ferris et al., 2008). It is a distressing social experience that can have a negative impact on psychological wellbeing and adjustment (Chen et al., 2024). In educational settings, ostracism can be particularly harmful to students and teachers, as it undermines basic needs, such as belonging, self-esteem, control, and a sense of meaningful existence (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Hou et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021).

Research highlights that experiences of ostracism can have a cascading effect on an individual’s self-perception and social behaviour (Hou et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021; Williams, 2007). For example, individuals who feel ostracised may become more vigilant to potential social threats, leading to a heightened sensitivity to rejection and increased feelings of social inadequacy (Niu et al., 2023). In turn, these individuals may withdraw from social interactions or engage in maladaptive coping behaviours, such as problematic smartphone use, to cope with feelings of loneliness and exclusion (Sun et al., 2021).

Ostracism is particularly detrimental to preservice teachers who are in the process of forming their professional identity (Polat et al., 2023). Within the context of preservice teachers, ostracism may contribute to a sense of professional isolation that reduces their confidence and motivation to engage in their educational communities. When preservice teachers feel excluded, it may significantly impact their social self-efficacy, i.e., their belief in their ability to form and maintain social connections (Bjorklund, 2019). Studies have shown that lower social self-efficacy due to ostracism can lead to avoidance of collaborative opportunities, reduced participation in learning communities, and ultimately feelings of professional dissatisfaction and disengagement (Hou et al., 2019; Niu et al., 2023). Therefore, exploring the associations among the sense of institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism can offer valuable insights into how teacher education programmes can better support preservice teachers in developing resilience and a strong professional identity.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Social Self-Efficacy

Social self-efficacy can play a significant role in mediating the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism, as it reflects an individual’s confidence in their ability to navigate social relationships within an interpersonal domain (Vatou et al., 2022). According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), self-efficacy influences on how individuals interpret and respond to their social environment. When preservice teachers feel valued and integrated into their teacher education programmes, they are more likely to develop a strong belief in their ability to engage in social interactions, seek support, and build professional networks. Conversely, when preservice teachers experience ostracism, it can significantly undermine their social self-efficacy beliefs. In this vein, ostracism can create feelings of rejection and inadequacy, which can lead preservice teachers to doubt their social abilities (Chen et al., 2024; Williams, 2007). This can create a vicious cycle in which reduced social self-efficacy makes preservice teachers more likely to avoid social interactions, further isolating them and reinforcing the sense of exclusion (Sun et al., 2021).

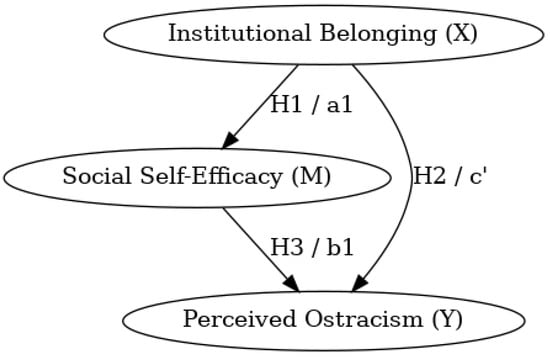

For preservice teachers, social self-efficacy can act as a buffering factor against the negative effects of perceived ostracism by increasing their sense of belonging within their teacher education programmes and, in turn, maintaining their commitment to the teaching profession (Chen et al., 2024; Ferris et al., 2008). Bjorklund et al. (2020) found that high levels of social self-efficacy encourage preservice teachers to engage more actively in collaborative learning, to seek support when needed, and to form meaningful connections within their academic community, enhancing their professional growth and development. Social self-efficacy can thus act as a mediator in this relationship, determining whether preservice teachers internalise their experiences of exclusion or use their social skills to navigate and overcome these challenges (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Diagram. Note: conceptual diagram examining (1) the indirect effect of institutional belonging (X) on ostracism (Y) through social self-efficacy (M) (a1 and b1) and (2) the direct effect of X on Y (c′).

3. The Present Study

The primary aim of the study is to investigate the level of preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy beliefs and to examine its associations with institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. This study also aims to test whether social self-efficacy mediates the direct relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. Three research questions (RQ) guided the study:

RQ1.

What is the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism among preservice teachers?

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Institutional belonging will have a negative relationship with ostracism.

RQ2.

What is the relationship between institutional belonging and social self-efficacy among preservice teachers?

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Institutional belonging will have a positive relationship with social self-efficacy.

RQ3.

Does social self-efficacy mediate the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism?

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Social self-efficacy will mediate the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

The participants in this study were preservice teachers (N = 271) enrolled in a four-year bachelor’s degree programme in early childhood education and care at a public university in Thessaloniki, Northern Greece. The sample included 74 (27.3%) first-year preservice teachers, 69 (25.5%) second-year preservice teachers, 64 (23.6%) third-year preservice teachers, and 64 (23.6%) fourth-year preservice teachers, with a mean age of 20.3 years (SD = 2.60 years). Demographic information collected during the survey included preservice teachers’ year of study and gender. A detailed description of the sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the sample.

4.2. Procedure

With the support of the university research team, 100 preservice teachers from each year group were invited to participate in an anonymous online questionnaire about their university experience. Email invitations and a QR code linking to the online questionnaire were distributed in October 2024 (the first term of academic year), and the questionnaire remained open for two weeks. The study received approval from the Ethics Advisory Board of the author’s department and adhered to all ethical guidelines. Participants provided informed consent prior to participation and received no additional credits or incentives.

4.3. Setting—Early Childhood Education and Care Bachelor Programme

The Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) bachelor programme is designed to equip future ECEC professionals with comprehensive knowledge and practical skills necessary for their role in ECEC settings. The curriculum is grounded in the principles of child development, health and safety, educational psychology, and pedagogy approaches tailored to early years as well as research methodology modules. Throughout the programme, preservice teachers engage in various activities such as group activities gaining hands-on experience in planning lessons, leading educational activities, and classroom management under the guidance of experienced ECEC teachers.

According to Bandura (1997), these experiences could be described as mastery experiences, a crucial source of self-efficacy, as preservice teachers build their confidence through successful teaching practice. Vicarious experiences are also embedded in the bachelor programme, as preservice teachers observe mentor teachers and peers, learning from their models of effective teaching. Additionally, the programme emphasises verbal persuasion through constructive feedback from mentor teachers and faculty supervisors, reinforcing preservice teachers’ skills and encouraging their efforts. Together, these elements could foster a strong sense of self-efficacy, preparing preservice teachers with the confidence and competence necessary to thrive in their future teaching careers.

4.4. Measures

4.4.1. Social Self-Efficacy

The Perceived Empathic and Social Self-Efficacy scale (Di Giunta et al., 2010) was used to examine preservice teacher’s social self-efficacy beliefs. The scale consists of 11 items that described two subscales: perceived empathic self-Efficacy (PESE, 6 items, e.g., “Recognise whether a person is annoyed with you?”) and perceived social self-efficacy (PSSE, 5 items, e.g., “Actively participate in group activities”). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not well at all) to 5 (very well). Higher scores indicate higher social self-efficacy beliefs. For the needs of this study, only the PSSE subscale was included in the survey. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the scale yielded satisfactory goodness-of-fit statistics (χ2 (df) = 90.2 (41), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.951; RMSEA = 0.066; SRMR = 0.046). In this sample, the internal consistency of PSSE was very good ω = 0.796.

4.4.2. Sense of Belonging

Institutional belonging was assessed with the five items developed by Sotardi (2022). An example item is “I feel safe at [institution]”. Participants responded to a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The CFA of the scale yielded satisfactory goodness-of-fit statistics (χ2 (df) = 4.31 (2), p = 0.116; CFI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.065; SRMR = 0.018). In this study, the omega’s ω coefficient was 0.759.

4.4.3. Perceived Ostracism

The 10-item Workplace Ostracism Scale (Ferris et al., 2008) was adopted to estimate perceptions of being social excluded. An example item is “Others refused to talk to you at [institution]”. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). A higher total score indicated higher perceived ostracism. The CFA of the scale yielded satisfactory goodness-of-fit statistics (χ2 (df) = 54.2 (26), p < 0.001; CFI = 0.979; RMSEA = 0.063; SRMR = 0.026). The omega’s ω coefficient was 0.913.

4.5. Data Analysis

To examine the study’s aims, a series of statistical analyses were conducted using the JAMOVI (ver. 2.6.2) to examine the relationships among the study’s variables. Outliers and the normal distribution of the data were checked before proceeding with the analyses. As no missing data were detected in this dataset, no imputation procedure was required. After this process, a total number of 271 individuals were considered valid cases for further analysis.

First, descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of the variables were computed to assess the distribution, central tendency, and the interrelationships of the study variables. In the next step, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimation method, appropriate for ordinal data to test the validity of the measurement model. This CFA included the three latent constructs of institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism. A combination of goodness-of-fit indices was used to test the hypothesised measurement model. As the χ2 statistic is highly influenced by the sample size, emphasis was placed on the comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR). The following values of the fit indices were considered acceptable: CFI and TLI with values ≥0.90 or 0.95, RMSEA and SRMR with critical values from ≤0.06 to ≤0.08, and SRMR with a cut-off value of <0.08 (Kline, 2015). Reliability analyses were also performed to assess the consistency of each measure.

Subsequently, a structural equation model (SEM) was estimated to examine the direct paths [institutional belonging -> social self-efficacy (H1) and institutional belonging -> perceived ostracism (H2)] and the indirect paths [institutional belonging -> social self-efficacy -> perceived ostracism (H3)]. Each construct was tested as a latent variable with several observed indicators: institutional belonging (4 items), social self-efficacy (5 items), and perceived ostracism (8 items). To test the mediation, a bootstrapping approach with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was conducted to assess the significance of the indirect effect of institutional belonging on perceived ostracism through social self-efficacy. The total, direct, and indirect effects are reported together with their standard errors and confidence intervals. The assumptions underlying the SEM were carefully considered. The relationships between the latent variables were assumed to be linear and additive. Multicollinearity was checked and found not to exist (no correlations exceeded r = 0.90). As the data were ordinal, normality was not assumed, and DWLS estimation was used.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables. The results showed high levels of social self-efficacy (M = 3.82, SD = 0.73), suggesting that, on average, participants feel confident in their ability to engage in social interactions within their educational environment.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

5.2. Measurement Model

To validate the structure of the proposed model and to assess the quality of the latent constructs, a full CFA was conducted using the DWLS estimation method appropriate for ordinal data. The results indicated a good fit (χ2 = 163, df = 116, p = 0.003, CFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.039, SRMR = 0.067). All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and above 0.40, indicating strong convergent validity across constructs.

5.3. Structual Model and Mediation Analysis

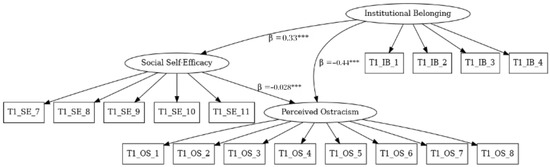

Following the validation of the measurement model, a structural equation model was estimated to test the hypothesised relationships between the study variables. Analyses revealed that institutional belonging significantly positively predicted social self-efficacy (H1: β = 0.33, p < 0.001). Also, a significant negative association was found between institutional belonging and predicted perceived ostracism (H2: β = −0.44, p < 0.001). Finally, a significant negative association was found between social self-efficacy and predicted perceived ostracism (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the test model with standardised path coefficients and structural model diagram with standardised coefficients.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the structural model with standardised coefficients (*** p < 0.001).

A bootstrapping mediation analysis with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was conducted to examine the mediating role of social self-efficacy between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism (H3). The analysis revealed that the indirect effect (a x b) of institutional belonging on ostracism through social self-efficacy was negatively significant (β = −0.06, p < 0.05), while the direct effect (c) of institutional belonging on perceived ostracism remained negatively significant (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). The total effect [c’ + (a × b)] of institutional belonging on perceived ostracism was negatively significant (β = −0.44, p < 0.001) indicating that social self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. The results of the mediation analysis are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The mediating effect of social self-efficacy between institution belonging and perceived ostracism.

6. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy beliefs and to better understand the relationships between institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism among preservice teachers. This study also examined the mediating role of social self-efficacy in the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. Grounded in social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), we expected that preservice teachers who have confidence in their perceived ability to interact socially with other members of their classroom and institution would report a positive sense of institutional belonging and experience low levels of perceived ostracism. The findings of this study supported all three research hypotheses.

This study found high levels of social self-efficacy among preservice teachers, suggesting that participants generally felt confident in their ability to engage in social interactions within their institution This finding is important, as social self-efficacy has been associated with resilience and professional identity development in preservice teachers (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Teachers who experience high levels of social self-efficacy are often better able to develop and maintain affective relationships with others (e.g., colleagues, parents, and children), seek support, and effectively manage classroom interactions (Zee & Koomen, 2016; Vatou et al., 2022).

6.1. Institutional Belonging as a Predictor of Social Self-Efficacy and Perceived Ostracism (H1 and H2)

The findings of this study revealed that feelings of institutional belonging were positively related to social self-efficacy in preservice teachers. This finding aligns with prior research that suggests feelings of belonging within an academic community positively influence self-efficacy in various domains (Haim-Litevsky et al., 2023; Strayhorn, 2023). Moreover, Bjorklund et al. (2020) found that preservice teachers who felt a sense of programme belonging experienced increased self-efficacy beliefs. This sense of belonging may support preservice teachers to see themselves as integral members of an educational network, thereby strengthening their commitment to the teaching profession (Strayhorn, 2023).

The positive association between institutional belonging and social self-efficacy could be further supported by the social cognitive theory, which posits that mastery and vicarious experiences as well as verbal persuasion are key sources of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). According to this theory, preservice teachers who felt high levels of belonging tend to engage more in meaningful interactions, receive positive feedback, and observe effective role models within their institutions. These factors may reinforce their social self-efficacy, which in turn enhances their ability to build and maintain positive relationships. These findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that a sense of belonging fosters social self-efficacy by providing a safe and encouraging environment in which preservice teachers feel valued and capable (Bardach et al., 2022; Sotardi, 2022).

The finding of a significant negative association between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism shows that a sense of belonging reduces feelings of exclusion and isolation (Hou et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021). It seems that preservice teachers who feel integrated and valued within their academic institution are less likely to perceive themselves as socially isolated. This finding echoes previous research indicating that feelings of ostracism can undermine preservice teachers’ wellbeing, engagement, and motivation, which in turn can lead to professional dissatisfaction (Hou et al., 2019; Niu et al., 2023; Polat et al., 2023).

6.2. The Mediating Role of Social Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Institutional Belonging and Perceived Ostracism (H3)

When it comes to examining the role of social self-efficacy as mediator, the results revealed a partial mediation in the relationship between institutional belonging and perceived ostracism. This means that when preservice teachers have a strong sense of belonging, they are likely to feel more confident in their social interactions, which can buffer against the negative effects of social exclusion. This finding is consistent with Bandura’s theory that individuals with high self-efficacy are more resilient in the face of social challenges (Bandura, 1997). This finding implies that preservice teachers with high social self-efficacy may perceive instances of exclusion as less threatening and feel better equipped to seek support in order to reduce the impact of ostracism on their wellbeing (Sun et al., 2021; Williams, 2007).

To summarise, by examining the above relationships, the study highlights how a strong sense of institutional belonging can positively influence preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy, which in turn can help to mitigate feelings of ostracism. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the social and psychological factors that shape preservice teachers’ experiences within educational settings and highlights the importance of fostering supportive and inclusive communities in teacher education programmes.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the current study need to be considered. First, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to offer causality about the relationships among variables. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies to track possible changes in institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism over time. Additionally, this study relied on self-reported data, which may introduce bias, as participants’ responses may be influenced by social desirability. As such, future studies could incorporate multiple sources of data, such as observational data or mentor ratings, to provide a more objective view of preservice teachers’ experiences. Another limitation is that the sample was drawn from a teacher education programme in Greece; thus, the findings cannot be easily generalised in other cultural and educational settings. Replicating this study in different educational settings could help to determine whether these relationships hold across different settings.

7. Conclusions and Implications

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the interplay between institutional belonging, social self-efficacy, and perceived ostracism among preservice teachers. The study showed that a strong sense of belonging can enhance preservice teachers’ social self-efficacy, which in turn can buffer against the negative feelings of ostracism. The mediation relationship highlights the importance of promoting both belonging and social self-efficacy within teacher education programmes. These elements could contribute not only to preservice teachers’ confidence and resilience but also to their ability to navigate the social demands of educational contexts (Le Cornu, 2013, 2016; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011, 2017; Vatou et al., 2024).

The findings of this study have several implications for practice. Institutions should prioritise the development of inclusive environments that foster a sense of community and belonging among preservice teachers. This could be achieved through mentoring programmes, peer support groups, and constructive feedback from mentors. These strategies could further support preservice teachers to gain confidence in their social interactions and reduce the likelihood of perceived ostracism. Additionally, institutions could benefit from developing a strategic plan for prevention and intervention that focuses on the promotion of social skills. Teacher education programmes could consider introducing social skills training to equip preservice teachers with tools for effective communication, conflict resolution, and collaborative engagement. These skills are essential for building positive relationships with mentors, peers, and future colleagues (Di Giunta et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2013). By fostering these social skills, teacher education programmes not only enhance preservice teachers’ mastery experiences but also prepare them for the collaborative demands of their future roles.

Author Contributions

All author contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection of the study were coordinated by A.V. Data analyses were conducted by A.V. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the grant titled ‘Social Self-Efficacy in Higher Education (SSEHE)’, awarded by the Special Account for Research Funds of the International Hellenic University. It falls under task 2 of the program ‘Measures to Promote Research through Financial Support to Laboratories and Institutes of the International Hellenic University’ (Code No. 81659).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving human participants in this study were performed following the ethical standards of the Department of the Early Childhood Education and Care and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration (Protocol Code: ΣΦ30/39 and date of approval 2-10-2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent forms were obtained from participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy and consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInerney, D. M., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bardach, L., Klassen, R. M., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Teachers’ psychological characteristics: Do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorklund, P., Jr. (2019). “Whoa. You speak Mexican?”: Latina/o high school students’ sense of belonging in advanced placement and honors classes. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 24(2), 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, P., Jr., Daly, A. J., Ambrose, R., & van Es, E. A. (2020). Connections and capacity: An exploration of preservice teachers’ sense of belonging, social networks, and self-efficacy in three teacher education programs. Aera Open, 6(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. Y., Lau, S., Nie, Y., Lim, S., & Hogan, D. (2008). Organizational and personal predictors of teacher commitment: The mediating role of teacher efficacy and identification with school. American Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 597–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Lin, X., Wang, N., Wang, Y., Wang, J., & Luo, F. (2024). When and how is depression associated with ostracism among college students? The mediating role of interpretation bias and the moderating role of awareness rather than acceptance. Stress and Health, 40(5), e3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2018). Workplace ostracism and job performance: Roles of self-efficacy and job level. Personnel Review, 48(1), 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Kupfer, A., Steca, P., Tramontano, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2010). Assessing perceived empathic and social self-efficacy across countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N. J., Alonzo, D., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (2020). Elements of a quality pre-service teacher mentor: A literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 92, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Litchfield, R. C., Islam, S., Weiner, B., Alexander, M., Liu, C., & Kulviwat, S. (2013). Workplace social self-efficacy: Concept, measure, and initial validity evidence. Journal of Career Assessment, 21(1), 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haim-Litevsky, D., Komemi, R., & Lipskaya-Velikovsky, L. (2023). Sense of belonging, meaningful daily life participation, and well-being: Integrated investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, N., Fan, J., Tan, J., Stuhlman, M., Liu, C., & Valdez, G. (2019). Understanding Ostracism from Attachment Perspective: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of International Students, 9(3), 856–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cornu, R. (2013). Building early career teacher resilience: The role of relationships. Australian Journal of Teacher Educatio, 38(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cornu, R. (2016). Professional experience: Learning from the past to build the future. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Permzadian, V., Fan, J., & Meng, H. (2019). Employees’ social self-efficacy and work outcomes: Testing the mediating role of social status. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(4), 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the literature. Association of Independent Schools of NSW. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H., Huang, P., Hou, N., & Fan, J. (2015). Social self-efficacy predicts Chinese college students’ first-year transition: A four-wave longitudinal investigation. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(3), 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S. L., Schutz, P. A., Rodgers, K., & Bilica, K. (2017). Early career teachers’ emotion and emerging teacher identities. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G. F., Shi, X. H., Yao, L. S., Yang, W. C., Jin, S. Y., & Xu, L. (2023). Social exclusion and depression among undergraduate students: The mediating roles of rejection sensitivity and social self-efficacy. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24198–24207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H., Karakose, T., Ozdemir, T. Y., Tülübaş, T., Yirci, R., & Demirkol, M. (2023). An examination of the relationships between psychological resilience, organizational ostracism, and burnout in K–12 teachers through structural equation modelling. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadieh, H., & Rezaei, M. (2024). A serial mediation model of sense of belonging to university and life satisfaction: The role of social loneliness and depression. Acta Psychologica, 250, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, H. B., Dawes, M. E., & Chong, S. S. (2023). Social self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goal progress among American college students: Testing temporal relations by gender and race/ethnicity. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 36(3), 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teachers’ feeling of belonging, exhaustion, and job satisfaction: The role of school goal structure and value consonance. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24(4), 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. M., & Betz, N. E. (2000). Development and validation of a scale of perceived social self-efficacy. Journal of Career Assessment, 8, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotardi, V. A. (2022). On institutional belongingness and academic performance: Mediating effects of social self-efficacy and metacognitive strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 47(12), 2444–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2023). Unraveling the relationship among engagement, involvement, and sense of belonging. In The impact of a sense of belonging in college (pp. 21–34). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X., Zhang, Y., Niu, G., Tian, Y., Xu, L., & Duan, C. (2021). Ostracism and problematic smartphone use: The mediating effect of social self-efficacy and moderating effect of rejection sensitivity. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21, 1334–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatou, A., Gregoriadis, A., Evagelou-Tsitiridou, M., Manolitsis, G., Mouzaki, A., Kypriotaki, M., Oikonomidis, V., Lemos, A., Piedade, F., Alves, D., Cadima, J., Michael, D., Charalambous, V., Agathokleous, A., Vrasidas, C., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2024). Cross-Cultural Validation of Teachers Social Self-Efficacy Scale: Insights from Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal. Education Sciences, 14, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatou, A., Gregoriadis, A., Tsigilis, N., & Grammatikopoulos, V. (2022). Teachers’ social self-efficacy: Development and validation of a new scale. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2093492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism: The kiss of social death. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. L., & Perrone, K. M. (2010). An examination of the role of attachment and efficacy in life satisfaction. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 796–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).