1. Introduction

The evaluation process can become a controversial moment in teaching performance since it involves obtaining a result from the entire teaching and learning process. The conflict arises when the grade awarded must be adjusted to the work performed in relation to what has been learned. Evaluation must be more than a mere instrumentalization of grading to catalog student performance. It is a process, per se, in which the structure, form, mode, and organizational capacity of the data obtained can take the teacher much further than mere grading (

Álvarez Méndez, 2001).

In search of a tool that allows recording and control and that can provide the evaluation process with a method that is by itself a complete change of process and practice is advocated for. The participatory action research methodology gains strength in the work of an involved researcher who directly involves all parties in the process and product; this is the teacher and, in this work, students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (hereinafter ASD).

Regarding evaluation at the stage of Compulsory Secondary Education for students with special educational needs (hereinafter ACNEE) and paying special attention to evaluating the process and progress of formative aspects related to the socio-educational field, it is difficult to find structured and quality evaluation beyond qualitative reports or record sheets. The instruments available for assessing ACNEE students are cataloged in purely subjective descriptions, lacking real justification and with little formative projection beyond descriptive lyricism that is repeated year after year throughout the educational stage. All of the above-described difficulties specific to the students referred to make adjusting to individual needs focused on full inclusion and equity in the teaching/learning process particularly relevant.

1.1. Students with ASD and Social Skills

Autism Spectrum Disorder (hereinafter ASD) is based on a disorder that encompasses an entire spectrum with different manifestations, degrees, and, as it cannot be otherwise, the delicacy that implies differences among all people when we talk about diversity (

Álvarez-López et al., 2014).

Students with ASD may show different manifestations of this disorder, involving both their behavioral repertoire and purely cognitive abilities, executive functions, and even their main characteristic: their form of social interaction. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (

American Psychiatric Association, 2014), characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder are defined as follows: “Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts (…) Restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities” (p. 50), thus specifying identifiable areas typical of this type of disorder. Additionally, among its main characteristics are diagnostic criteria as follows (

American Psychiatric Association, 2014):

Criterion A: Persistent deficits in reciprocal social communication and social interaction. Criterion B: Restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Criteria C and D: These symptoms are present from early childhood and limit or impair everyday functioning (p. 53).

Among the other characteristics or manifestations associated with ASD are the following: linguistic deficiencies ranging from complete absence of speech due to language delays to poor understanding of others’ speech; echolalia or unnatural, overly literal language use even when formal language abilities (e.g., vocabulary grammar) remain intact; and use deteriorated reciprocal social communication (p. 53).

As indicated earlier, the DSM-V (

American Psychiatric Association, 2014) states that functional impairment is not equal in all individuals with the same disorder, showing variability depending on the characteristics of the individual and environment, giving meaning to the term autistic spectrum. According to the DSM-V (

American Psychiatric Association, 2014), “symptoms cause clinically significant impairment social occupational other important areas usual functioning” (p. 51).

For students with ASD, working on social skills becomes a fundamental aspect of achieving autonomy in daily life, keeping in mind particular characteristics of this type of disorder deficit associated with social competence, especially in the areas of communication and interaction (

Wing, 2002).

Given the difficulty in the problem intervention described, the study proposal made sense in coherence with the entire teaching–learning process, including specifically the transformation of the evaluation process, completely adapting interests to the individual needs of students. This could enhance cooperative, collaborative aspects of constructing learning social competencies in a reality context that is playable through gamification.

1.2. Evaluation in an Educational Innovation Method

Continuous transformation in teaching methods has increased the frenetic escalation appearance of new methodologies, classroom practices, and material applications for learners (

Cornellá et al., 2020). Additionally, increased interest in new methodologies is accompanied by increased use of Information Communication Technologies (ICT)—a fact worth emphasizing, given that educational field technology and methodological evolution seem to walk hand in hand (

Carneiro, 2019).

It is the arduous task of teachers to find the right key that can favor the learning of their students and, at the same time, provide an improvement in educational quality; this represents a daily challenge in teaching practice. The sum of the factors involved, together with the large number of available methods, can pose a real puzzle, especially when adjusting to ideal educational practice in didactic programming. Among the techniques and methodologies that can be found in the classroom are “problem-based learning”, “project-based learning”, “collaborative learning”, “cooperative learning”, “flipped classroom”, “game-based learning”, etc. In this small list, the constant appearance of new platforms and digital tools can also be added. The flagrant technological use to which ICT subjects teachers is joined by an incessant cascade of resources, in which educational practice is further compromised (

Akram et al., 2022). Thus, the erratic use of methods and tools becomes a constant to consider, avoiding falling into the use of fleeting educational trends.

The work developed here aims to go a step further in the search for improving educational quality and best practices. For this purpose, evaluation has been considered an essential process.

In previous lines, the importance of a method adjusted to each context, moment, or group has been mentioned; therefore, it should be expected that such practice is chosen based on criteria and justification. Considering the aforementioned, an integral part of the evaluation process is intention. Through the development of a tool based on the previously described purpose, an effective instrument is also intended to be added to the overall evaluation process, both in data collection and implementation and extraction of conclusions, shaping a method that goes beyond the end.

To conclude, it is essential to mention that despite the existence of educational intervention programs based on a multitude of methodologies, each with its particularities in practice, there is one element they all have in common: the evaluation process (

Medina-Díaz & Verdejo-Carrión, 2020).

Evaluation is a part of the teaching–learning process that becomes indispensable when the objective aims to go beyond mere numerical grading. The program chosen for this study, and more specifically, the evaluation section of said program, offers interesting aspects considering three fundamental axes: (a) educational innovation, (b) attention to individual differences linked to ASD students, and (c) holistic evaluation.

2. Objectives

The general objective of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of an evaluation procedure that follows an embedded methodology to assess the acquisition of social skills in ASD students enrolled in Compulsory Secondary Education.

The general objective is articulated into two specific objectives as described below:

To determine if there is an improvement in the acquisition or level of achievement in social skills as the program progresses so that the indicated actions can be concluded.

To determine if the methodological design of evaluation allows for comparing the level of acquisition of aspects related to social skills included in the proposal based on the hours spent in the ASD classroom program.

3. Working Hypotheses

The approach for the working hypotheses in this research revolves around the development and evolution of the experience carried out, along with the analysis of the proposed evaluation methodology. These hypotheses are described below.

Firstly, it is considered that there is an improvement in the effective performance of social skills as students progress in the ASD classroom program. That is, as the academic year progresses, better performance in the described task is observed.

Secondly, it is assumed that the proposed methodological design, understood as both the process and product of this research, allows for evaluating the level of acquisition of social skills in the classroom based on the number of hours invested.

4. Methodology

4.1. Methodological Approach

Given the characteristics of the longitudinal study proposal presented and based on the collection and treatment of the study’s data and variables, a quasi-experimental study following a quantitative methodological approach was conducted. This approach allows for the extraction of data and conclusions to test the hypotheses of this study.

4.2. Sample and Sampling Procedure

4.2.1. Target Population

Students diagnosed with ASD enrolled in Compulsory Secondary Education in the Community of Madrid in a regular regime and within a preferred center for ASD students equipped with an ASD classroom.

4.2.2. Accessible Population

ASD students within the age range of Compulsory Secondary Education (12–16 years) with the exception of two extraordinary repetitions, extending this age up to 18 years and adding an extraordinary repetition up to 19 years. The students referred to are part of a preferred educational center for ASD students in public Compulsory Secondary Education in the Community of Madrid.

4.2.3. Sampling Procedure

Access to the sample follows a non-probabilistic convenience sampling procedure. Several inclusion criteria were considered: having a diagnosis of ASD with any level of affectation, following the DSM-V diagnostic criteria; attending the ASD classroom at least 1 h per week in the educational center under investigation; being between 12 and 19 years old; having been referred by the Guidance Department of the educational center; and having obtained the consent of the parent/guardian responsible for the minor. Exclusion criteria include not having an ASD diagnosis and/or not having obtained the informed consent signature of the responsible person.

4.2.4. Sample Description

The sample consisted of 18 subjects (N = 18), with 83% male (n = 15) and 17% female (n = 3) between 12 and 19 years old. Specifically, 72.2% are 12 years old (n = 13), 16.7% are 13 years old (n = 3), and 11.1% are 16 years old (n = 2). The hours in the program ranged from a minimum of 360 to a maximum of 5760 with an average of 1530 h (SD = 1746.52). Specifically, the actual distribution of hours in the ASD classroom program is as follows: 55.6% (n = 10) spent 360 h; 5.6% (n = 1) 540 h; 11.1% (n = 2) 1440 h; 5.6% (n = 1) 3240 h; 11.1% (n = 2) 3600 h; 5.6% (n = 1) 4320 h; and 5.6% (n = 1) 5760 h.

4.2.5. Variables

This study considered dependent, independent, and control variables. Their fundamental characteristics are described below.

4.2.6. Independent Variables

Number of hours of participation in the program. This is an ordinal quantitative variable. It refers to the number of hours invested in the embedded gamification proposal included in the ASD classroom program.

Trimester. This is a nominal qualitative variable. It refers to the three-month period corresponding to each of the school evaluations (

Real Academia Española, 2024). It takes the values 1, 2, or 3, depending on the trimester referred to.

Embedded methodology for evaluating social skills based on a gamification program. This methodology consists of 5 evaluation stages, which assess the level of acquisition of social skills according to different evaluation criteria that differ in the level of concreteness of social skills. Each of these evaluation stages corresponds to a different independent variable. These are described below.

Evaluation Stage 1 (E1). Ordinal quantitative variable. Corresponds to the first stage of social skills evaluation, based on the embedded gamification model. This variable takes values ranging from 1 to 10 obtained from the computation of completed activities.

Evaluation Stage 2 (E2). Ordinal quantitative variable, corresponding to the second stage of social skills evaluation based on the embedded gamification model. This variable takes values from 1 to 10 obtained from a rubric that evaluates cooperative learning.

Evaluation Stage 3 (E3). Ordinal quantitative variable, corresponding to the third stage of social skills evaluation based on the embedded gamification model. This variable takes values from 1 to 10 obtained from a rubric that evaluates cooperative learning.

Evaluation Stage 4 (E4). Ordinal quantitative variable, corresponding to the fourth stage of social skills evaluation based on the embedded gamification model. This variable takes values from 1 to 10 obtained from a rubric that evaluates cooperative learning.

Evaluation Stage 5 (E5). Ordinal quantitative variable, corresponding to the fifth stage of social skills evaluation based on the embedded gamification model. In this last stage, this variable takes values ranging from 1 to 10 obtained from a rubric that evaluates the level of acquisition of basic, advanced, affective, negotiation, stress, and planning social skills.

The variables TOTAL E1, TOTAL E2, TOTAL E3, TOTAL E4, and TOTAL E5 are ordinal quantitative variables. They correspond to the total scores obtained in each of the intervention proposals carried out. They refer to the equivalent of the score obtained throughout a complete course.

4.2.7. Dependent Variables

The dependent variables considered in this study are linked to the level of acquisition of social skills. However, each evaluation stage incorporates an information collection instrument that distinguishes different levels of concreteness of the social skills construct. The dependent variables evaluated at each stage of the embedded social skills evaluation method are detailed below.

Skills evaluated in E1. The proposal corresponding to the first stage of the program was evaluated as either achieved or not achieved for the following criteria: active participation in the classroom, active participation outside the classroom, social interaction, respect for speaking turns, and intentional communication. Thus, achieving or not achieving each of the 12 activities proposed per trimester (repeated in each of them) granted a point of progress that was recorded at the end of the trimester on a scale of 1 to 10.

Skills evaluated in E2. In this second version of the first evaluation stage, the assessment dynamics remained similar to the previous one. However, the method for evaluating the degree of achievement or progress within this stage was carried out using an evaluation rubric that assesses cooperative learning, distinguishing the following criteria: group efficiency control, work quality, teamwork, contributions, time management, attitude, and conflict resolution. This facilitates both quarterly progress tracking and individual tracking in each activity. The values taken in the rubric fluctuate between 1 and 10 within each of the criteria to be evaluated depending on the performance level of each.

Skills evaluated in E3. For this third evaluation stage, the method for evaluating the degree of achievement or progress was maintained using the same rubric to assess cooperative learning. As in the previous stage, the criteria distinguished were group efficiency control, work quality, teamwork, contributions, time management, attitude, and conflict resolution. The values taken in the rubric were maintained, fluctuating between 1 and 10 within each of the criteria evaluated and depending on the performance level of each.

Skills evaluated in E4. In the fourth evaluation stage, the evaluation method used in E3 was maintained without making any modifications regarding the use of the instrument, evaluation criteria, and rubric values so that the evaluation method and instrument were stabilized within the program.

Skills evaluated in E5. For the fifth and final evaluation stage, two complementary instruments were used. The method for evaluating the degree of achievement or progress within this stage was carried out using the evaluation rubric that assesses cooperative learning already used in the previous stages. However, the scores obtained in each of the activities carried out and evaluated through this rubric were transferred to a tracking sheet of the teaching–learning process, allowing the monitoring of the entire process and distinguishing the following criteria around social skills: basic, advanced, affective, negotiation, stress, and planning social skills. The values taken in the tracking sheet fluctuated between 1 and 10 within each of the criteria depending on the performance level of each.

4.2.8. Control Variables

Gender. This is a nominal qualitative variable corresponding to the physiological and biological characteristics that define men and women of each of the study participants (

World Health Organization, 2024). It takes the following values: 01 = Male, 02 = Female.

Age. This is an ordinal quantitative variable. It corresponds to chronological age, that is, the amount of time lived from birth to the time of data recording. It also corresponds to the moment when each of the subjects begins their participation in the embedded gamification proposal included in the ASD classroom program.

5. Data Analysis

For data processing, the statistical program SPSS version 28 was used. The applied tests are indicated below.

First, a descriptive analysis was performed by applying the descriptive statistic of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation, minimum, and maximum) to the total scores of each evaluation stage. Relative percentage frequencies were also applied to the independent variable hours in the program.

Second, to test the hypotheses of this study, inferential statistics were used by applying non-parametric tests. Although the normality assumption was met in most dependent variables (

p > 0.05; according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), the sample was small (n < 30) and did not follow a probabilistic random procedure; thus, free distribution tests were indicated for this case (

Berlanga Silvente & Rubio Hurtado, 2012).

To test the first hypothesis and corroborate if the first specific objective of this study is achieved, the non-parametric test for K-related samples, Friedman’s test, was applied, considering the different evaluations of the five stages as dependent variables and each trimester of the academic year as the independent variable. If the null hypothesis was met (p > 0.05), the values obtained in the evaluations of the three trimesters belonged to the same distribution.

Finally, to test the second hypothesis and verify if the second objective of this study was met, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied, as it aims to determine if the values of the dependent variables (level of performance in social skills based on the total evaluation of each stage) vary depending on the number of hours students attend the ASD classroom. This test is an extension of the Mann–Whitney U test and represents an excellent alternative to the one-factor completely randomized ANOVA, such as the assignment of a certain number of hours to a specific student (

Berlanga Silvente & Rubio Hurtado, 2012).

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of central tendency and dispersion for each of the evaluations applied.

Secondly,

Table 2 shows the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test statistic to check if the dependent variables fit a normal distribution. The variables studied follow a normal distribution if the statistical significance level (

p) is greater than 0.05 (

p > 0.05).

Analyzing whether there were statistically significant differences among evaluation stages (Stage 1 (E1), Stage 2 (E2), Stage 3 (E3), Stage 4 (E4), Stage 5 (E5)) and project evaluations (E1TOTAL, E2TOTAL, E3TOTAL, E4TOTAL, E5_TOTAL) using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, a p < 0.200 (p > 0.05) was obtained, which does not allow the null hypothesis to be rejected (Ho is accepted). Therefore, there was no significant difference between the scores of the different methodological proposal projects.

Table 3 and

Figure 1 shows the results of the Friedman test for each evaluation stage to test the first hypothesis.

Since the significance level (p > 0.05) accepts the null hypothesis, there were no significant differences in the level of social skills acquisition at the first evaluation stage.

Table 4 and

Figure 2 shows the results of the Friedman test for each evaluation stage to test the first hypothesis.

Since the significance level (p > 0.05) accepts the null hypothesis, there were no significant differences in the level of social skills acquisition at the second evaluation stage.

Table 5 and

Figure 3 shows the results of the Friedman test for each evaluation stage to test the first hypothesis.

There were no significant differences in the level of social skills acquisition at the third evaluation stage (p > 0.05).

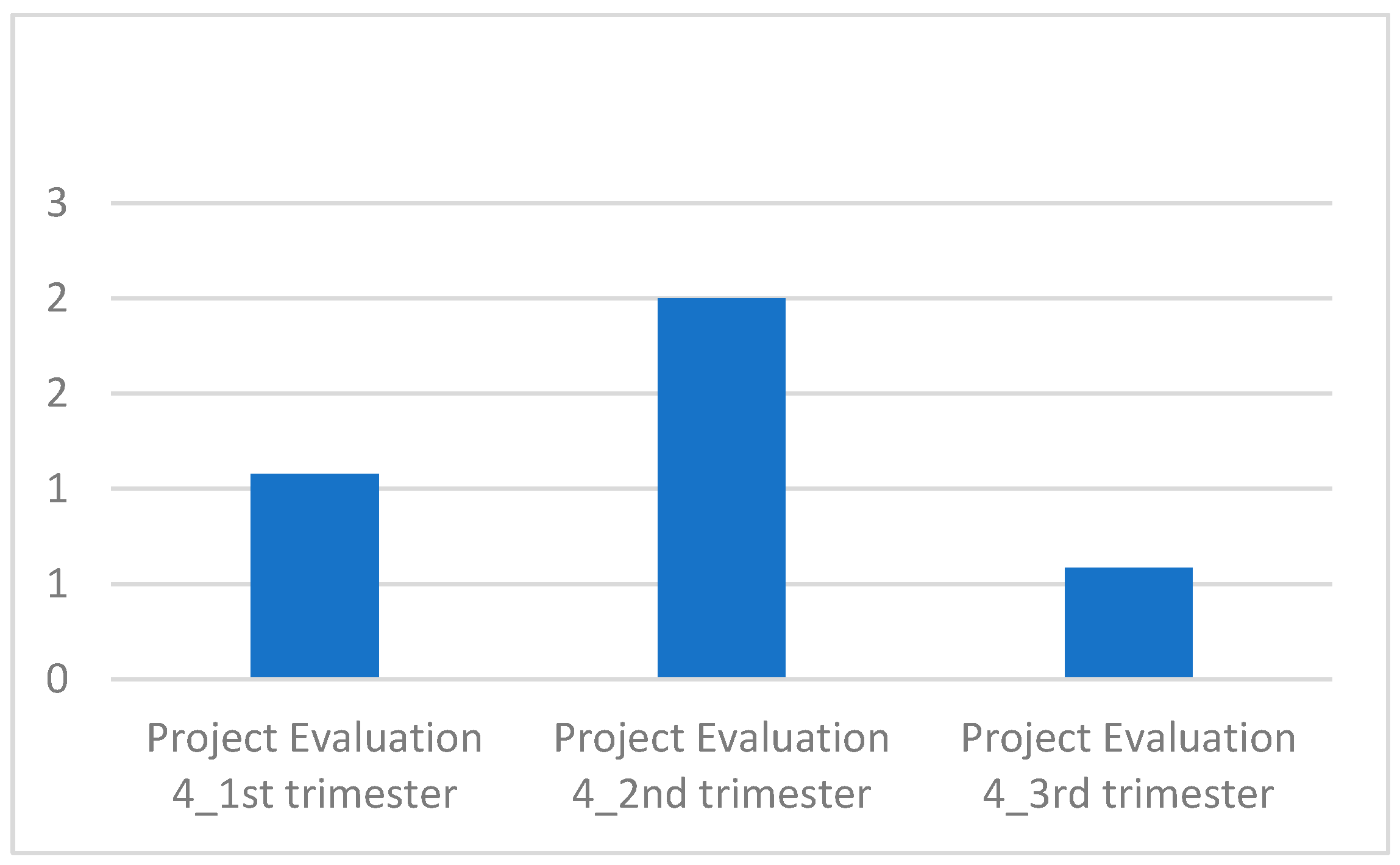

Table 6 and

Figure 4 shows the results of the Friedman test for each evaluation stage to test the first hypothesis.

Since the significance level (p > 0.05) accepts the null hypothesis, there were no significant differences in the level of social skills acquisition at the fourth evaluation stage.

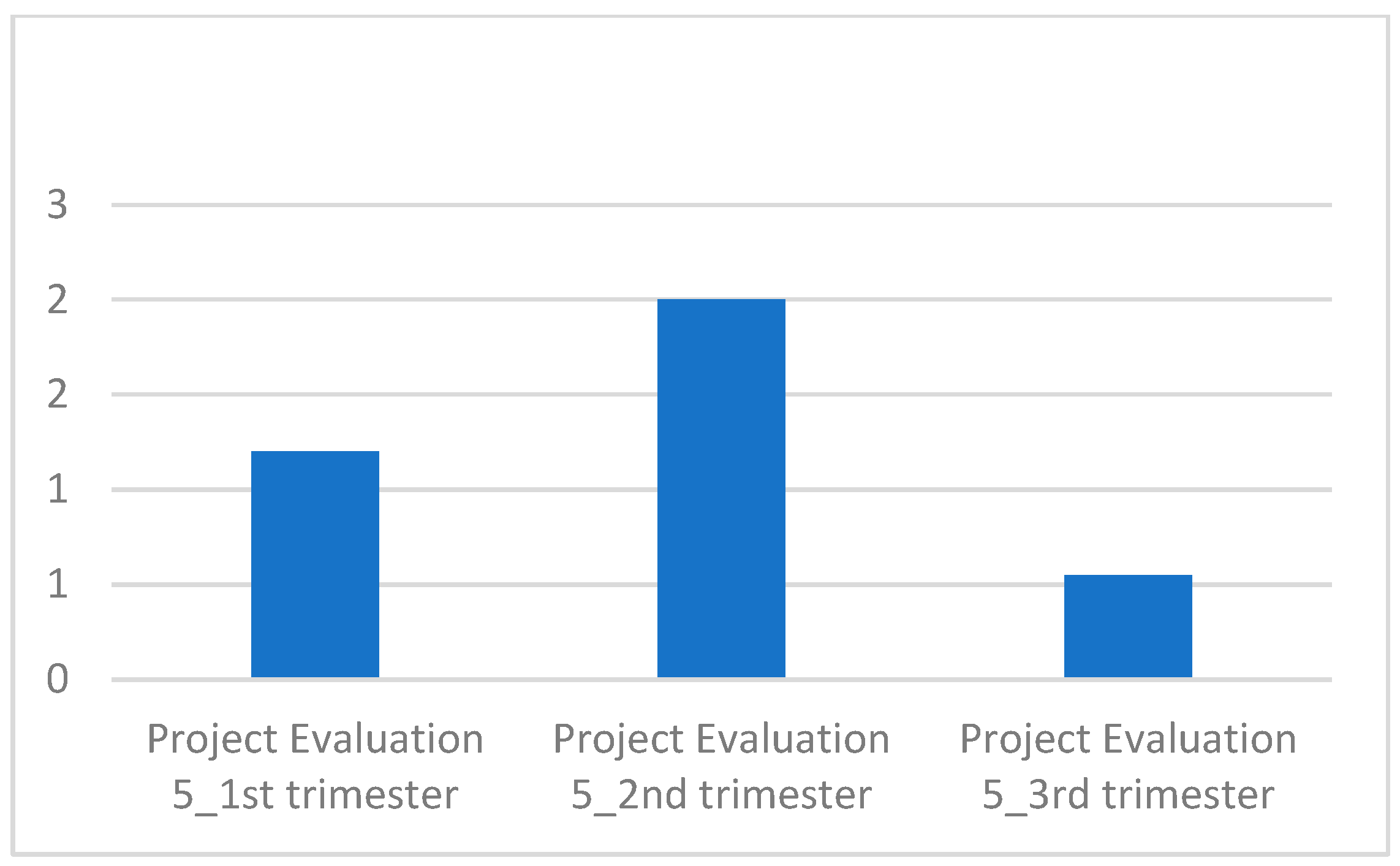

Table 7 and

Figure 5 shows the results of the Friedman test for each evaluation stage to test the first hypothesis.

There were no significant differences in the level of social skills acquisition at the fifth evaluation stage (p > 0.05).

Finally, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to test the second hypothesis. The results are presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9.

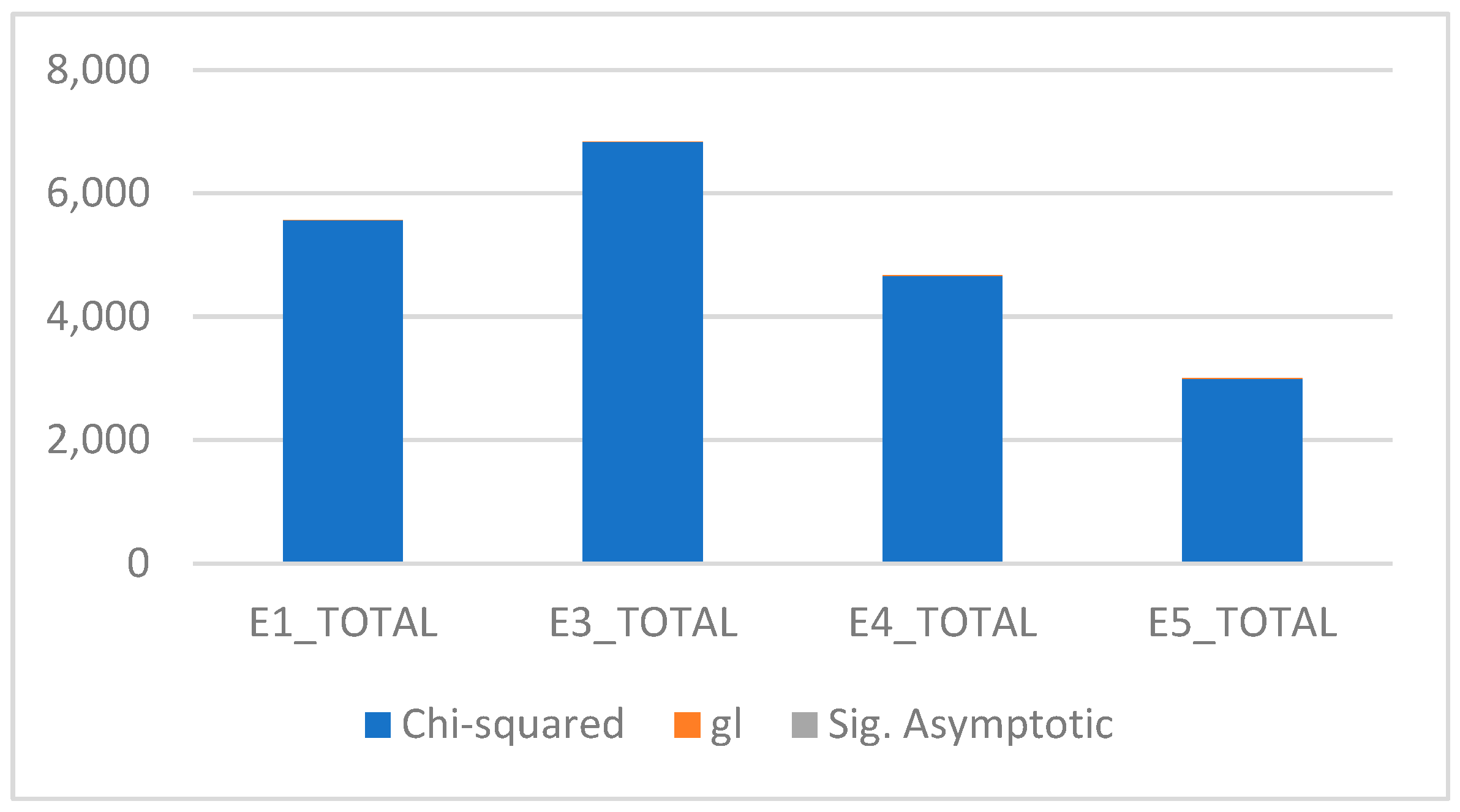

Table 8 and

Figure 6 shows the results of average rank resulting from the application of the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Table 9 and

Figure 7 shows the results of Kruskal–Wallis test for each stage based on the number of hours students attend the ASD classroom.

Since the significance level (p > 0.05) accepts the null hypothesis, the level of social skills acquisition in the classroom improved based on the number of hours invested.

6. Discussion

In the literature, there is a lack of studies similar to the one carried out. On the one hand, there are programs for social skills training, and on the other, there are methodological programs that rely on play or ICT for learning. However, no proposals have been found that encompass a complete program structured in stages under an embedded model that allows the monitoring and tracking of social skills learning with ASD students, as presented in this study.

For social skills training, the Social Skills Program (P.H.S.) by

Verdugo et al. (

2003) was found, which is a proposal for training these skills aimed at a population with intellectual disabilities, with an age range from 12 years to adulthood. This wide age range, combined with the use of the program in a population with intellectual disabilities, makes it unsuitable for the program carried out.

Similarly, we highlight the Social Interaction Skills Teaching Program (PEHIS) by

Monjas Casares (

2002), which is a proposal that covers an age range from 3 to 16 years, with an organization of social skills training stratified into thirty social interaction skills grouped into six areas: basic social interaction, making friends, conversational skills, related to feelings, emotions, and opinions, interpersonal problem-solving, and finally, relating to adults. Although this is a complete program that allows work on a wide variety of aspects related to social skills, there is no monitoring and tracking in this study.

Secondly, linking the search for similar programs to the experience carried out with the use of ICT and ASD students, we highlight a study conducted by

Adeleke (

2023). This study explored the impacts of intelligence and software on the education of children with ASD. The findings of the research showed that providing the necessary support and inclusive academic opportunities for students is essential. When individualized support is offered, autistic students can implement valid skills to achieve improvements in their educational progress.

Another study conducted by

Ök et al. (

2023) aimed to understand the opinions of special education teachers regarding the application of various innovative Special Education programs, some of them aimed at individuals with autism. This educational program was called “Together with Autism”. The game was applied to five students with autism in the presence of a special educator, and data on the subject were collected from five special education teachers based on semi-structured courses, as well as interviews composed of nine qualitative questions. After conducting and analyzing the study, they found that the gamified proposal provided an unparalleled contribution to the teaching–learning process, given the playful nuance it provided to the entire process.

In all of the described cases, there are similarities with the experience carried out in this study, supporting the methodological use and the importance of intervention in the areas described. However, no experience comprehensively encompassed the method, evaluation, and monitoring in the way the current study has.

7. Conclusions

The study conducted was based on an educational innovation experience supported by gamification and aimed at learning social skills with ASD students. This study specifically focused on the evaluation process as the object of study. The goal was to determine the effectiveness of the methodology used to evaluate social skills through the implementation and analysis of this experience in different stages.

The longitudinal analysis of a gamification-based learning method, embedded and focused on evaluation, confirms the use of evaluation as a process that permeates the entire teaching–learning action, allowing the monitoring of its development in terms of adaptation, flexibility, and individualization of teaching.

In this non-probabilistic sample, there were no statistically significant differences in the test results between the different evaluation stages under the chosen methodology. Therefore, it can be stated that, for the participating group, each of the gamified learning proposals were equally effective, as they were followed without altering the obtained results, allowing the monitoring, flexibility, and adjustment of the entire teaching–learning process. Finally, the consistent grades obtained concerning the stated objectives and hypotheses confirm the importance for students of the work carried out from an embedded methodology that gave meaning and coherence to the process.

Part of the explanation for the lack of statistical significance may be due to two situations: on the one hand, the small sample size, and on the other hand, more than half of the sample (55.6%) only spent 360 h in the classroom, and the majority (67%) attended only 2 days a week. Therefore, the time factor and participation in the program played a determining role.

8. Research Limitations

The limitations of this work were, firstly, the non-probabilistic sampling procedure, which does not allow for the generalization of the results, as they are limited to this sample. Since the data were obtained only in this classroom, different results could be expected with a larger sample. Secondly, the limited and variable time available to carry out the intervention work with the students should be noted. Finally, the unequal proportion of men and women should be taken into account.

9. Future Work Lines

Finally, as a proposal for improvement regarding the experience carried out, an extension of the intervention and educational innovation work is suggested, taking the method beyond the walls of the ASD classroom, permeating the entire Educational Center Program, and becoming part of its own methodology and identity. We advocate for the use of active and innovative methodologies as valuable tools in addressing diversity and educational inclusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C.; methodology, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C.; software, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C.; validation, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., formal analysis, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., investigation, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., resources, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., data curation, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., writing—original draft preparation, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., writing—review and editing, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., visualization, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., supervision, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., project administration, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C., funding acquisition, N.M.P., C.B.B. and N.F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adeleke, M. (2023). Innovation unleashed: Empowering autistic learners with revolutionary strategies and technology. Jurnal Pedagogi dan Pembelajaran, 6(3), 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, H., Abdelrady, A. H., Al-Adwan, A. S., & Ramzan, M. (2022). Percepciones de los docentes sobre la integración de la tecnología en las prácticas de enseñanza-aprendizaje: Una revisión sistemática. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 920317. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.920317/full (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de trastornos mentales (5th ed.). Asociación Américana de Psiquiatría. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-López, E. V., Barragán-Espinosa, J., Calderón-Vázquez, I., Torres-Córdoba, E., Beltrán Parrazal, L., López-Meraz, L., Manzo, J., & Morgado-Valle, C. (2014). Autismo: Mitos y realidades científicas. Revista Médica de la Universidad Veracruzana, 14, 36–41. Available online: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/veracruzana/muv-2014/muv141f.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Álvarez Méndez, J. (2001). Evaluar para conocer. Examinar para excluir. Barcelona: Morata. Revista Electrónica Diálogos Educativos, 6(12), 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga Silvente, V., & Rubio Hurtado, M. J. (2012). Clasificación de pruebas no paramétricas: Cómo aplicarlas en SPSS. REIRE: Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 5, 101–113. Available online: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/15045/00720123000098.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Carneiro, R., Toscano, J. C., & Díaz, T. (2019). Los desafíos de las TIC para el cambio educativo. Available online: https://www.oei.es/uploads/files/microsites/28/140/lastic2.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Cornellá, P., Estebanell, M., & Brusi, D. (2020). Gamificación y aprendizaje basado en juegos. Consideraciones generales y algunos ejemplos para la enseñanza de la geología. Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la Tierra, 28(1), 5–19. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/ECT/article/view/372920/466561 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Medina-Díaz, M. d. R., & Verdejo-Carrión, A. (2020). Validez y confiabilidad en la evaluación del aprendizaje mediante las metodologías activas. Alteridad, 15(2), 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjas Casares, M. I. (2002). Programa de enseñanza de habilidades de interacción social (PEHIS) para niños y niñas en edad escolar. CEPE. [Google Scholar]

- Ök, N., Alagöz, A., Uysal, O., Sakarya, Y., & Gürsoylar, G. (2023). An innovative educational digital game design for primary school children with Autism. Necatibey Eğitim Fakültesi Elektronik Fen ve Matematik Eğitimi Dergisi, 17, 744–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. (2024). Cultura. In Diccionario de la lengua española. Real Academia Española. Available online: https://dle.rae.es (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Verdugo, M. Á., Monjas, M. I., San José, T., San Román, M. E., & Alonso, P. (2003). PHS: Programa de habilidades sociales: Programas conductuales alternativos. Amarú. [Google Scholar]

- Wing, L. (2002). El autismo en niños y adultos. Una guía para la familia. Editorial Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Definiciones. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/sexual-health#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).