Leadership for Student Participation in Data-Use Professional Learning Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Student Participation

- Children are listened to, as shown in the way of working and policy of the school.

- Children are supported in expressing their views, both in the availability of a range of activities to help children express their views and in the school’s policy requirements.

- Children’s views are taken into account in the decision-making process in the school, and the school has a policy requirement that the children’s views must be given proper weight in decision making.

- Children are involved in decision-making processes in the school, as acknowledged in both procedures and policy.

- Children share power and responsibility for decision making in the school, in terms of both policy requirements and procedures to enable children and adults to share power and responsibility.

2.2. Leadership for Student Participation in Data Use

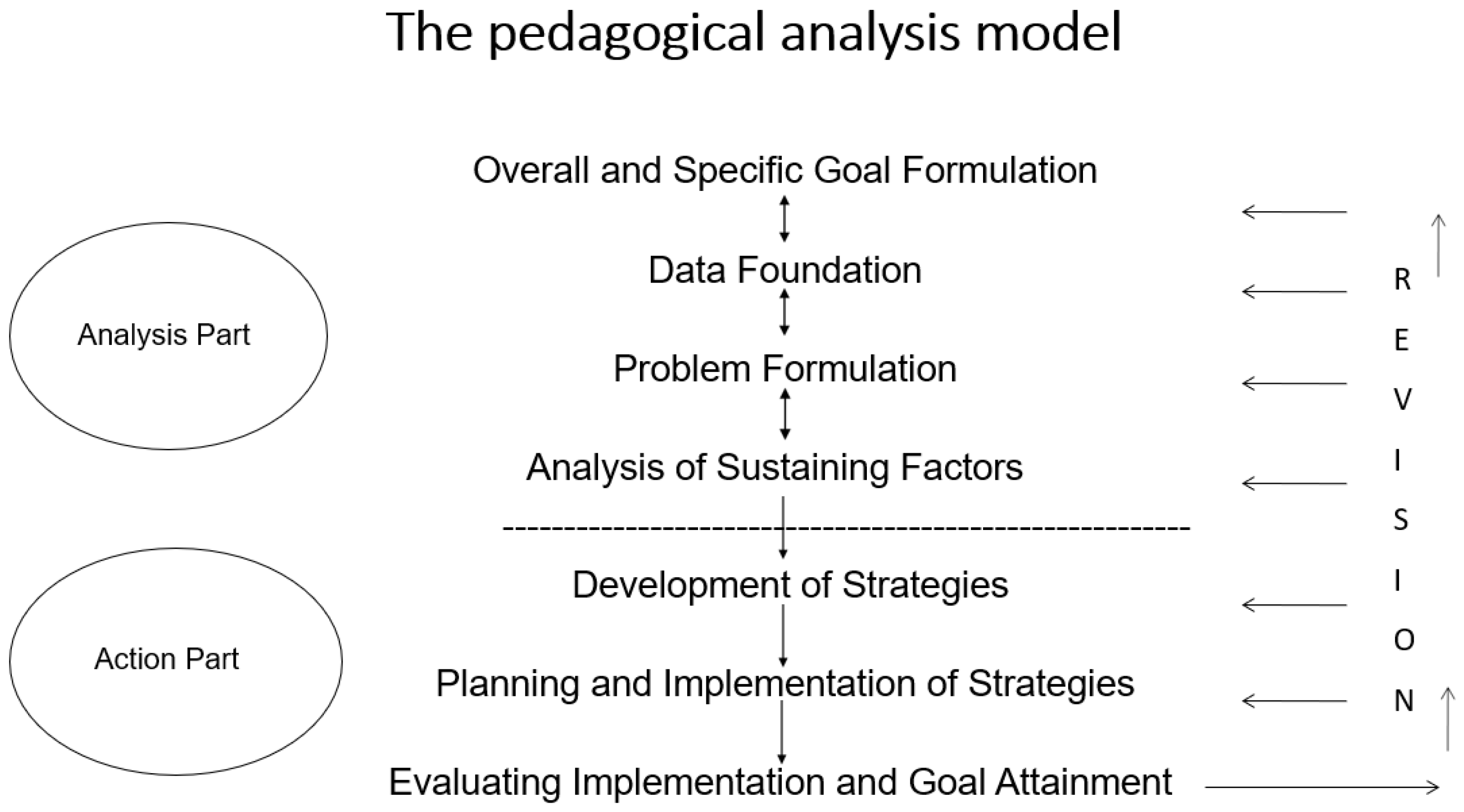

3. PA-Model Intervention in This Study

3.1. Collaboration in Data-Informed Decision Making by Students, Teachers, and School Leaders in the PA-Model Intervention

3.2. Participants

- Overall goal: Each student PLC should start by establishing an overall goal that they want to work on, related to the themes of a survey that is used for data collection in this step. The survey covers the following aspects: well-being, motivation, bullying, student participation, classroom structures and rules, and so forth. The teacher collects the input from the students, and, then, either the teacher decides (Level 4) on the purpose based on the student input or the teachers and students collectively decide (Level 5) on the purpose (e.g., via a whole-classroom discussion, via voting). In this step, it is important that a shared purpose is developed within the entire classroom.

- Data foundation: This step of the PA model involves systematically gathering and organizing information that represents various aspects of the school. Both quantitative (e.g., surveys, assessment results) and qualitative (e.g., classroom observations, interviews) data can be collected. After the data are collected, the quality (i.e., reliability and validity) of the data need to be checked. It is not possible to draw correct conclusions from poor-quality data. In this step, the teacher (Level 4) or the student PLCs together with the teacher (Level 5) decide which data to collect given the goal from the previous step and how to verify the quality of the collected data.

- Problem formulation: In this step, a final problem is formulated, related to the overall purpose and based on the data collected. For example, each student PLC can individually formulate a problem, after which all the problems are collectively discussed in the classroom, and a final shared problem is formulated by the teacher (Level 4) or the teachers and students together (Level 5). Problem definitions are often phrased in the form of statements or why questions.

- Specific goal formulation: Specific goals are related to the overall goal and should be formulated in a way that clearly expresses what is intended to be achieved. These goals should encompass both short-term and long-term objectives and be formulated in a way that allows for the evaluation of goal attainment. Here, for example, each PLC in the class can formulate a realistic and feasible goal that they present to the class, after which the teacher facilitates a discussion between the PLCs. The teacher can take the input of this discussion into account to formulate the final goal (Level 4). Alternatively, teachers and students could together decide (Level 5) on the final problem, for example, by voting for the best problem formulation.

- Analysis of factors that contribute to the problem: These factors are key elements within the pedagogical context that likely contribute to the problem. The analysis aims to identify and examine these factors to gain a deeper understanding of their impact on students’ situations and the perpetuation of difficulties. Here, for example, each PLC in the class can suggest possible factors that contribute to the problem and the data needed to investigate this. Then, all the PLCs present this information to each other. After the presentations, the teacher can decide (Level 4) which PLC is going to be responsible for investigating which possible causes and which data to collect. Alternatively, teachers and students could decide together (Level 5) on which PLC will investigate which possible causes.

- Development of strategies: The development of strategies is based on the analysis of the contributing factors. It is important to address multiple contributing factors simultaneously and to work systematically on implementing the strategies over time. When choosing strategies, it is advisable to rely on research-based knowledge wherever possible. In this step, the student PLCs brainstorm about possible strategies based on the identified contributing factors (for example, in their PLC or with the whole classroom) or select from a top-three list of strategies suggested by teachers. Either the teacher ultimately decides which strategies are going to be implemented (Level 4) or this is decided jointly (Level 5).

- Planning and implementation of strategies: When planning the implementation of strategies, careful consideration should be given to how they will be executed, who will be responsible for their implementation, and when they will be carried out. The teacher can plan and implement these strategies together with the student PLCs. The teacher can ultimately decide this (Level 4), or the decision can be made with the students (Level 5).

- Evaluating implementation and goal attainment: Planning and conducting an evaluation of the work performed increases the likelihood of realizing new practices. The evaluation of implementation and goal attainment should take place regularly and continually. It is important to focus on progress, that is, the extent or degree of improvement. Regardless of whether the goals are achieved or not, it is important to evaluate the potential reasons for this. In this step, for example, each student PLC can develop an evaluation plan, and, then, the teacher decides who does what (Level 4), or the teacher and students can make this decision together (Level 5).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Instruments and Data Collection

4.2. Ethical Considerations

4.3. Data Quality and Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Student Participation in the Use of Data

5.2. Organizing and (Re-)Designing the Organization

5.3. Managing the Teaching and Learning Programme

5.4. Understanding People and Supporting Their Development

If we had any questions, we could just ask the school leaders. We have asked for support and help throughout the whole implementation process, including when a school leader has been doing observations in the classroom. We did receive support and help when we needed it.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

6.2. Limitations and Implications for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Code Book

- Organizing and (re)designing the organization: Clear vision for student participation in data use (why is the school working with…)

- ○

- Making this a priority (facilitation, resources, scheduling).

- ○

- Coherence between student participation in data use and the school organization (connecting, e.g., taking into account at different levels coordination within the school so it can be organized and carried out; connection of school’s goals and intervention goals).

- Managing the teaching and learning plan: Planning

- ○

- Monitoring (e.g., observations by school leaders).

- ○

- Evaluation (e.g., by asking the students systematically what their experiences were).

- Understanding people and supporting their development: Providing support

- ○

- Being available and accessible (e.g., listening to teachers, being available for meetings/questions with teachers or students about the intervention).

- ○

- Being able to support connections and building trust (e.g., connections with the university coaches; building trust among teachers and students to work with the intervention).

- ○

- Being a role model (for student participation in data use, being actively engaged/participating).

- ○

- Being knowledgeable about this, as well as sharing knowledge (being able to answer questions about the intervention, communicating findings, and insights to others).

- New code(s) emerging from the data about leadership supporting student participation in data use not captured in the codes: gatekeeping, school leader first to implement and experiment (see Table 4, italics).

| Leadership Practices | Code Definition | Example Quote |

| Organizing and (re-) designing the organization | ||

| Vision and goals | Development of and communication of vision and goals | “The path was, in a way, created as we walked.” (SL1) |

| Managing the teaching and learning plan | ||

| Facilitating | Human resource management, use of time, Time for collaboration among staff | “We have indeed allocated time for it in the school’s overarching plans: which sessions in the different classes should be used for what, who should do what, what roles the various individuals should have, and what teachers need from the school’s leadership, and vice versa.” (SL1) |

| Planning | Staffing of teaching, monitoring student progress in learning, facilitating/shielding the employees | “The school leader has led the project, held onto it, and made plans and structures so the intervention could be carried out regularly” (SL4) |

| Understanding people and supporting their development | ||

| Actively involved | Actively involved in the pilot | “Because it’s also about being interested, right? That you are actually there and see what they are doing. But one of us was always there, so someone from the leadership team was always involved.” (SL5) |

| Supporting and motivating | Providing support | “After each round of observation, we always discussed it immediately on the same day. While the session was still fresh, we let the teachers reflect on how they thought it went. Yes, then we talk about it, right? About any possible tips, right? What could have been done differently there.” (SL5) |

| Modelling | Being a role model for student participation in data use | “And then it was us who started, it was me and the principal who sort of started inside (in the classes) with students, the first time.” (SL5) |

| 1 | Professional Learning Networks using data for learning and student engagement. |

| 2 | The second and fourth author were involved in designing this study and in writing this paper. They were not involved in coaching any participants, nor were they involved in data collection. |

| 3 | Italics mean new codes. |

References

- Anderson, S., Leithwood, K., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading data use in schools: Organizational conditions and practices at the school and district levels. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 292–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansyari, M. F., Groot, W., & De Witte, K. (2020). Tracking the process of data use professional development interventions for instructional improvement: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 31, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Flood, J. (2020). The three roles of school leaders in maximizing the impact of Professional Learning Networks: A case study from England. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capobianco, B. M., & Feldman, A. (2010). Repositioning teacher action research in science teacher education. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Deakin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Datnow, A., & Hubbard, L. (2016). Teacher capacity for and beliefs about data-driven decision making: A literature review of international research. Journal of Educational Change, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutch Secondary Education Council. (2021). Convenant versterking samenspraak leerlingen [Agreement on increasing student participation]. Agreement by the Dutch Secondary Education Council and the Dutch National Student Interest Group. Available online: https://www.vo-raad.nl/nieuws/laks-en-vo-raad-tekenen-convenant-voor-versterking-inspraak-leerlingen (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Fielding, M. (2001). Beyond the rhetoric of student voice: New departures or new constraints in the transformation of 21st century schooling? In Forum for promoting 3–19 comprehensive education (Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 100–109). FORUM. [Google Scholar]

- Forfang, H., & Paulsen, J. M. (2019). Under what conditions do rural schools learn from their partners? Exploring the dynamics of educational infrastructure and absorptive capacity in inter-organisationallearning leadership. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 3(4), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forfang, H., & Paulsen, J. M. (2021). Linking school leaders’ core practices to organizational school climate and student achievements in Norwegian high-performing and low-performing rural schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(1), 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gebre, E. H. (2018). Young adults’ understanding and use of data: Insights for fostering secondary school students’ data literacy. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 18(4), 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarek, J., & Kallemeyn, L. M. (2020). Does teacher data use lead to improved student achievement? A review of the empirical evidence. Teachers College Record, 122(12), 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, A. M., & Nordahl, T. (2024). Pedagogisk analyse: En modell for kvalitetsvurdering og kvalitetsutvikling i skolen [Pedagogical analysis: A model for quality assessment and quality development in schools]. In H. Forfang, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Ledelse av kvalitetsarbeid i skolen (pp. 111–136). Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. UNICEF International Child Development Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, M. A., & Scheerens, J. (2013). School leadership effects revisited: A review of empirical studies guided by indirect-effect models. School Leadership & Management, 33(4), 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Holquist, S. E., Mitra, D. L., Conner, J., & Wright, N. L. (2023). What is student voice anyway? The intersection of student voice practices and shared leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(4), 703–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, M., Poortman, C. L., Schildkamp, K., & Forfang, H. (2025, February 10–14). Student involvement in the use of data in professional learning communities: Level of involvement and effects. ICSEI Congress [Paper presentation], Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen, M. M. F., Myhr, L. A., & Nordahl, T. (2024). Elevenes medvirkning i kvalitetsarbeidet [Student participation in quality work]. In M. Paulsen Jan, & H. Forfang (Eds.), Ledelse av kvalitetsarbeid i skolen (pp. 136–160). Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson, J. B., Cho, V., & Wayman, J. C. (2016). Student-involved data use: Teacher practices and considerations for professional learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. P. (2003). What every teacher should know about action research (3rd ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. A., & Hall, V. (2022). Redefining student voice: Applying the lens of critical pragmatism. Oxford Review of Education, 48(5), 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. K., & McNaughton, S. (2016). The impact of data use professional development on student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2021). A review of evidence about equitable school leadership. Education Sciences, 11(8), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful leaders transform low-performing schools (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, U., & Nowak, P. (2012). Effects of student participation in decision making at school. A systematic review and synthesis of empirical research. Educational Research Review, 7(1), 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandinach, E. B., & Jimerson, J. B. (2016). Teachers learning how to use data: A synthesis of the issues and what is known. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A. (2012). Interventions promoting educators’ use of data: Research insights and gaps. Teachers College Record, 114(11), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A., & Farrell, C. C. (2015). How leaders can support teachers with data-driven decision making: A framework for understanding capacity building. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(2), 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Meelissen, M., Maassen, N., Gubbels, J., van Langen, A., Valk, J., Dood, C., Derks, I., ’t Zandt, M. I., & Wolbers, M. (2023). Resultaten PISA-2022 in vogelvlucht [PISA results at a glance]. University of Twente. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D. L. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106(4), 651–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, T. (2016). Bruk av kartleggingsresultater i skolen: Fra data om skolen til pedagogisk praksis [Using survey results in schools: From school data to pedagogical practice]. Gyldendal akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Overordnet del—Verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen [Core curriculum—Values and principles for primary and secondary education]. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- OECD. (2019). An OECD learning framework 2030. In The future of education and labor (pp. 23–35). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman, C. L., Brown, C., & Schildkamp, K. (2022). Professional learning networks: A conceptual model and research opportunities. Educational Research, 64(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortman, C. L., & Schildkamp, K. (2012). Alternative quality standards in qualitative research? Quality & Quantity, 46, 1727–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Rinnooy Kan, W. F., Munniksma, A., Volman, M., & Dijkstra, A. B. (2023). Practicing voice: Student voice experiences, democratic school culture and students’ attitudes towards voice. Research Papers in Education, 39(4), 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roald, T., Køppe, S., Bechmann Jensen, T., Moeskjær Hansen, J., & Levin, K. (2021). Why do we always generalize in qualitative research? Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V., & Gray, E. (2019). What difference does school leadership make to student outcomes? Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(2), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. M. (2010). From instructional leadership to leadership capabilities: Empirical findings and methodological challenges. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkamp, K., Poortman, C. L., Ebbeler, J., & Pieters, J. M. (2019). How school leaders can build effective data teams: Five building blocks for a new wave of data-informed decision making. Journal of Educational Change, 20(3), 283–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children & Society, 15(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. (2019). Student voice and children’s rights: Power, empowerment, and “protagonismo”. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of teacher education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijbos, J., & Engels, N. (2023). Micropolitical strategies in student-teacher partnerships: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives on student voice experiences. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Przybylski, R., & Johnson, B. J. (2016). A review of research on teachers’ use of student data: From the perspective of school leadership. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 28, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boom-Muilenburg, S. N., de Vries, S., van Veen, K., Poortman, C., & Schildkamp, K. (2022). Leadership practices and sustained lesson study. Educational Research, 64(3), 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Scheer, E. A., & Visscher, A. J. (2018). Effects of a data-based decision-making intervention for teachers on students’ mathematical achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(3), 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Visscher, A. J., & Fox, J. P. (2016). Assessing the effects of a school-wide data-based decision-making intervention on student achievement growth in primary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 53(2), 360–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennergren, A. C., & Blossing, U. (2017). Teachers and students together in a professional learning community. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(1), 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yonezawa, S., & Jones, M. (2007). Using students’ voices to inform and evaluate secondary school reform. In International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school. Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Levels of Participation | Openings | Opportunities | Obligations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 5 | Are you ready to share some of your adult power with children? | Is there a procedure that enables children and adults to share power and responsibility for decisions? | Is it a policy requirement that children and adults share power and responsibility for decisions? |

| Level 4 | Are you ready to let children join your decision-making processes? | Is there a procedure that enables children to join in decision-making processes? | Is it a policy requirement that children must be involved in decision-making processes? |

| Level 3 | Are you ready to take children’s views into account? | Does your decision-making process enable you to take children’s views into account? | Is it a policy requirement that children’s views must be given due weight in decision making? |

| Level 2 | Are you ready to support children in expressing their views? | Do you have a range of ideas and activities to help children express their views? | Is it a policy requirement that children must be supported in expressing their views? |

| Level 1 | Are you ready to listen to children? | Do you think in a way that enables you to listen to children? | Is it a policy requirement that children must be listened to? |

| School (Type) | Teachers in the School | Number of Students in the School | Teachers Participating in PULSE | Classrooms Participating in PULSE | Grade Level(s) for the Participating Classrooms (Age Range in Years) | Students (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School 1 (secondary) | 68 | 545 | 1 | 1 | 8 (13–14) | 30 |

| School 2 (primary) | 35 | 353 | 2 | 3 | 5, 6, 7 (10–13) | 7 * |

| School 3 (primary) | 28 | 324 | 1 | 1 | 7 (12–13) | 25 |

| School 4 (secondary) | 25 | 179 | 3 | 3 | 9 (14–15) | 60 |

| School 5 (primary) | 13 | 113 | 2 | 2 | 5, 6 (10–12) | 37 |

| Respondents | School Leader | Teachers |

|---|---|---|

| School 1 | 1 | 1 |

| School 2 | 1 | 2 |

| School 3 | 1 | 1 |

| School 4 | 1 | 3 |

| School 5 | 2 | 2 |

| School | Organizing and (Re)Designing the Organization: Clear Vision for Student Participation in Data Use | Managing the Teaching and Learning Plan: Facilitation and Planning | Understanding People and Supporting Their Development: Providing Support, Involvement, and Modelling | Levels of Student Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School 1 (secondary) | Goals developed in collaboration with the teachers Effort to reach consensus on ‘student participation’ | Regular meetings (periodic) emphasizing and facilitating teachers’ participation in networks Gatekeeping3 | Observation, feedback, individual support | 4 |

| School 2 (primary) | Goals and expectations not communicated School leader carried out the intervention themself | Scheduled meeting Implementation jointly planned by school leaders and teachers School leader first to implement and experiment | Modelling of desired practices Provided support when needed | 4 |

| School 3 (primary) | Goals developed in collaboration with teachers Highlighted the coherence between previous school development and PULSE project | Scheduled meetings Extra time for teachers’ participating in the pilot Implementation plan, strategy for enhancing teachers’ knowledge Gatekeeping | Participation in teacher PLCs Emphasis on support and feedback Observations | 4–5 |

| School 4 (secondary) | Lack of emphasis on project goals Search for meaning and direction throughout the whole implementation process | Regular meetings, entire staff and teacher PLCs involved in the pilot Emphasizing and facilitating teachers’ participation in networks Gatekeeping | Monitoring Participation in teachers’ PLCs Observations, feedback, and support | 4–5 |

| School 5 (primary) | Emphasis on and communication of goals to all teachers | Regular meetings for whole staff and grade-level teams, extra time for teachers in the pilot Implementation plan Gatekeeping | Modelling of desired practices Actively involved in implementation Support, also provided individual support | 4–5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forfang, H.; Poortman, C.L.; Jenssen, M.M.; Schildkamp, K. Leadership for Student Participation in Data-Use Professional Learning Communities. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050548

Forfang H, Poortman CL, Jenssen MM, Schildkamp K. Leadership for Student Participation in Data-Use Professional Learning Communities. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050548

Chicago/Turabian StyleForfang, Hilde, Cindy Louise Poortman, Mette Marit Jenssen, and Kim Schildkamp. 2025. "Leadership for Student Participation in Data-Use Professional Learning Communities" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050548

APA StyleForfang, H., Poortman, C. L., Jenssen, M. M., & Schildkamp, K. (2025). Leadership for Student Participation in Data-Use Professional Learning Communities. Education Sciences, 15(5), 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050548