Abstract

Studies have documented a striking rise in income inequality and opportunity gaps in young children’s access to literacy. Recognizing the need, this study examines the local laundromat as an organizational broker and how specially designed spaces within this setting may support children’s literacy-related activities in under-served neighborhoods. Three laundromats in neighborhoods were examined. This year-long study examined changes in children’s activities resulting from the design changes alone, and subsequent changes when trusted messengers from the neighborhood supported their culturally and linguistically diverse traditions. The results suggest that everyday spaces in neighborhoods can serve as cultural niches that become important sites for learning.

1. Introduction

Early literacy development is a social process, embedded in the relationships, activities and settings in the everyday lives of young children (McLane & McNamee, 1990). In these settings, family members, and other caregivers will play critical roles in children’s early experiences, serving as language mentors, offering help and encouragement, and communicating their beliefs about language and learning early in life. Children will use these everyday experiences to make connections between talking, playing, reading, and writing based on the opportunities available to them and on how people around them engage with language and print. Consequently, children’s earliest socialization experiences will be shaped by these proximal influences, along with the priorities, expectations, and local practices held by their broader cultural community (Gutierrez & Rogoff, 2003; van Bergen et al., 2016).

There is a growing interdisciplinary consensus that children’s developing language and literacy learning must be understood in relation to cultural practices (Adamson et al., 2021; Larson et al., 2020). This sociocultural perspective highlights the social processes underlying developmental change, and the critical role of the social context in facilitating language and literacy learning opportunities. It also draws on ecological constructs developed from activity theory to better articulate the interdependencies between the person and context in producing developmental change (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Tharp and Gallimore (1988) described the activity setting as a meaningful way to integrate culture, local contexts, and individual function. Accordingly, activity settings include the participants who may assist the child, the roles or cultural scripts that might govern the interaction, and the setting or purpose of the activity (Cole, 1990; Weisner et al., 1988).

Typically, studies in early learning have focused on activity settings in early care and education classrooms or in homes, examining the dyadic relationships between the adults and children (Au, 1998; Hadley et al., 2022). However, this sociocultural perspective calls attention to the multiple spaces that might serve as activity settings, and to the adults who might assist in young children’s learning. It suggests that everyday places such as grocery stores, barbershops, and nail salons may create unique social and cultural niches with meaningful and contextualized language and literacy experiences for children seeking to understand their world (Delgado, 1997; Hanner et al., 2019). For example, in a recent study of black-owned barbershops, barbers took on the role of trusted messengers, sharing their cultural values and the transformative potential of reading while cutting children’s hair. Surveys showed that children in these sites were more likely to identify themselves as readers compared to those in the control, business-as-usual barbershops (Neuman, 2022). Building on an asset-based cultural perspective, it highlights the potential for creating powerful learning arrangements in everyday spaces that map on to local interests, values, contexts and practices. From this perspective, such everyday spaces are physical and social spaces that merge the experiences and knowledge (s) of learners’ home communities and networks with those of more formal, privileged spaces such as schools (Moje et al., 2004).

In this study, we examine how the local laundromat in three neighborhoods can promote opportunities for children’s language and literacy development. We describe how trusted messengers, respected members from the local community who are seen as a credible, relatable sources of information engage with families and their children in ways that support their cultural and linguistically diverse traditions (Chau et al., 2023). In these everyday learning spaces, young learners and these adults engage in informal conversations, generating and shaping experiences that bridge the activity settings of home, school, and neighborhood. Building on an asset-based cultural perspective, activities in these local settings—guided by trusted messengers may create meaningful learning opportunities that reflect the community’s interests, values, and everyday practices. In so doing, we argue that such nontraditional settings can serve to complement children’s development, and to provide families with information resources and more equitable opportunities for children’s learning.

1.1. The Role of Neighborhood Institutions as Organizational Brokers in Accessing Resources and Opportunities

Children’s experiences in their neighborhoods play a role in shaping their aspirations, learning opportunities, and interactions with others (McCoy et al., 2023). Yet, in recognizing the intersecting roles of communities, families, and institutions in nurturing young children and leveraging local resources, we must also attend to how the histories of structural inequities, economic circumstances, and discriminatory practices in many low-income communities have constrained children’s access to resources and opportunities (Massey & Denton, 1993; Sharkey, 2013). Studies have shown that many children have limited access to books and other rich reading materials in communities (Neuman & Moland, 2019; McGill-Franzen & Allington, 2013). In one study, for example, 832 children in a book desert neighborhood would have to share one book to read during the summer months (McGill-Franzen & Allington, 2013; Neuman & Moland, 2019; Neuman et al., 2021). In addition, families living under difficult economic circumstances are likely to have less disposable income to engage their children in enrichment-oriented activities during the year and over the summer months (Duncan & Murnane, 2014; Ludwig et al., 2012; Phillips, 2011). Coley and her colleagues (Coley et al., 2016) found that higher-income families were able to spend over 60 percent more time on enriching materials and opportunities for their children such as educational programs, literacy materials, and extracurricular activities than their lower-income peers. In short, differences in access to these learning resources are likely contributors to differences in school readiness and achievement.

Consequently, studies have shown that residents in under-served and poor communities often turn to local neighborhood institutions such as the church, recreation centers, and childcare centers to maintain social ties to others and to access valuable resources like information about schools (Small, 2009; Stack, 1974; Wilson, 1997). These neighborhood institutions may often serve as organizational brokers (Klinenberg, 2018; Small, 2006), a term employed in organizational and social networking studies that connects two separate areas of a network: the organization and the individual (Burt, 1992; Stovel & Shaw, 2013). Serving in a community capacity-building role (Chaskin, 2001), an organizational broker refers to a physical establishment located in a neighborhood with built ties to other organizations that serves the needs of its local clientele. Delgado (1997), for example, examined how beauty salons in one Latino community became an informal social service agency, providing culturally appropriate help for customers in need of information on formal and informal resources. In this analysis, Delgado found that this nontraditional setting served as an indigenous source of support, where individuals could congregate and exchange concerns and advice with staff who shared the same ethnicity, socioeconomic circumstances, and religion.

Within these neighborhood institutions there are individuals who help to make the connections across organizations, say from neighborhood to school. A trusted messenger is an individual, beyond one’s inner circle, that people have come to trust and to turn to for trustworthy information (Feldmann et al., 2023). Studies suggest that they may come from many walks of life; they may be nurses, librarians, and members of the clergy, as well as hairdressers, childcare staff and local neighbors. Among the common features, however, is their authenticity, their practical know-how, and their ability to relate to others without being judgmental (Burt, 1992, 2004). In these neighborhood institutions, trusted messengers often communicate with others informally through casual conversation. For example, in his study of childcare centers as organizational brokers, Small (2009) found that the informality of the exchanges between parents and staff was affected by the ethnic and cultural similarity between the families and their teachers. Centers where the staff were Latino immigrants, for example, engaged in more casual and trusting relationships, allowing them to broker more resources with Latino parents than other centers serving Latino immigrants.

Institutions that act as organizational brokers can be public or private, religious or secular, for-profit, or not for profit. In urban neighborhoods, community centers, churches, bodegas, and other places where locals are likely to gather to exchange information may serve in the capacity of organizational broker. In these spaces, parents and children are likely to encounter familiar faces from the neighborhood, establishing social ties that can connect them to other resources and new opportunities (Pearman, 2020). Some locals in these settings may take on the role of trusted messengers who are seen by others in the community as credible information providers within their social network.

Therefore, the concept of organizational brokerage is to connect people to other people and to tie people to organizations that might serve their needs and provide services that might benefit them. It stands in contrast to deficit-oriented models of poor neighborhoods that have focused on distress and disadvantage (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2010). Rather, it highlights the interaction of human capital, organizational resources, and social capital existing within a neighborhood that can be leveraged to improve or maintain the well-being of their community (Chaskin, 2001).

1.2. The Laundromat as an Organizational Broker

Although many neighborhood institutions may serve as informal educational spaces, not all may act as organizational brokers. Neighborhood institutions are likely to differ in the ways in which they operate, and their norms of behavior. For example, there are neighborhood institutions, like community-based child-care programs, which may seek to disrupt educational inequity, creating mechanisms to establish social capital among families as a bridge between home and school discourses. However, there are other community-based educational spaces that have become beholden to the same standardized and measures of success as their public-school counterparts, essentially reproducing the status quo, and continuing to marginalize communities of color (Baldridge et al., 2017). Out-of-school programs such as Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL), designed to foster young learners’ interest in science, are increasingly required to demonstrate effectiveness through empirical evidence, with future funding often tied to measurable gains in standardized achievement scores. DiMaggio and Powell (1983) describe such institutional influences as ‘coercive’ pressures,’ often stemming from outside agencies that may establish mandates or regulations in exchange for resources (see, for example, 21st century community learning centers’ regulations URL: (https://www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/formula-grants/school-improvement/nita-m-lowey-21st-century-community-learning-centers (accessed on 3 March 2025).

In contrast, as a neighborhood institution, a laundromat may act as a passive organizational broker, providing a physical space for social interaction and social networking, a neighborhood-centric space that acknowledges the lived realities of people in their community and affirms their identities (Baldridge, 2020). As a fixture in many under-resourced communities, the laundromat has often served as an informal conduit to other resources and organizations. Particularly in low-income, renter-occupied communities, families are likely to spend about 156 min per week at the laundromat, often with their young children in tow (Holland, 2021). With time between wash- and dry- cycles running from 38 to 45 min, informal interactions between customers and staff members and among customers themselves are common (see coinlaundry.org) (URL accessed on 5 December 2024). For example, in a previous study, Neuman (2023) found that customers socialized and shared information on such topics as immigration and housing services, and exchanged information about their children’s difficulties in school. Given that over 90% of customers are repeat customers, and these are open for many hours (Cruz, 2024), laundromats may serve as an important neighborhood institution for organizational brokering.

1.3. Language and Literacy Learning in Informal Spaces

These neighborhood institutions may also provide an opportunity for children’s language and literacy learning in the early years. Studies suggest that everyday experiences, even the most mundane, are sources of learning for the young child (Phillips, 2011). Through their talk, gestures, and pretend play, children discover different ways of making, interpreting and communicating meaning. Early literacy experiences may include pretending to read a story, writing a letter to Santa, playing with blocks, drawing and scribbling, all of which involve the use of symbols (e.g., words, gestures, marks on paper) to represent and express their ideas. These early symbolic modes are thought to serve as ‘bridges to literacy’ as children begin to master a complex set of understandings, attitudes, expectations as well as specific skills related to written language (McLane & McNamee, 1990).

Consequently, the range of activities in which children are involved, whether it is cooking and cleaning up after meals, shopping, or doing laundry, can engage them in these symbolic activities and conversations with their caregivers that are rich in potential for expanding their social and cultural world. Because of their shared lives, parents frequently relate present to past experiences, bridging known and new information, building and extending children’s knowledge base (Rogoff & Lave, 1984; Tizard & Hughes, 1984). Conversations and shared periods of joint focus in parent–child interactions in one’s home and/or second language (Tomasello, 2000; Tompkins et al., 2017), along with positive affect, are known to support language development and cognitive growth.

Yet, there is some evidence that other adults, such as teachers and trusted messengers who come from a similar linguistic and cultural community as the children themselves, may connect meaningfully in ways that support intersubjectivity (Larson et al., 2020; Rogoff, 1990), the sharing of common ground so crucial for language development. In the natural course of interaction, these adults may speak to children in their native language, actively supporting their linguistic strengths (Cycyk & Hammer, 2020; Duran et al., 2016). They may also use language-promoting strategies such as engaging in conversational exchanges in the native language and in English (Adamson et al., 2021; Castro et al., 2011). A convergence of evidence has shown that these practices may have reciprocal effects on children’s overall language development, strengthening children’s native language and English language skills (Cunningham & Graham, 2000; Marchman et al., 2020).

These exchanges by skilled, trusted messengers may share some of the common features of parent–child talk. Having something in common, such as neighborhood experiences, may form the basis of the conversational ‘duet’ that lays the foundation for language development (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2018). A recent longitudinal study between these conversational turns and vocabulary development, for example, highlighted the dynamic interplay between the two, with growth in conversational turns predicting growth in vocabulary and vice versa, showing their mutual influence across children’s development (Donnelly & Kidd, 2021). In the course of these conversations, adults may introduce novel words related to the context, which, in addition to their communicative function, play an important role in shaping language development (Montag et al., 2018).

Living in the community in which children reside, trusted messengers are also likely to share cultural practices, values, and experiences with their conversational partners (Cycyk & Hammer, 2020). This shared understanding may include the flexible use of multiple languages or language varieties—a practice known as translanguaging—which allows children to draw on their full linguistic repertoires to make meaning, communicate, and learn (Garcia, 2009). Trusted messengers are likely to be empathetic and caring, cognizant of the injustices and biases based on race, ethnicity, social class, and/or gender that have influenced interactions with others, and children’s opportunities to learn (Gay, 2010). Some may see themselves as change agents, using cultural knowledge and frames of reference from their neighborhood to make learning encounters more real and relevant to young children (Nasir et al., 2012). Ladson-Billings (2014), for example, maintains that such cultural knowledge can empower children intellectually, socially, and emotionally because it uses known cultural referents to convey knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Children and families who feel that the activities of a trusted messenger align with their cultural beliefs—seeing their culture as a strength—may be more inclined to participate in programs, which could ultimately enhance children’s outcomes.

There is emerging evidence that these culturally and linguistically responsive practices may affect young children’s interests and engagement in early literacy activities (Portes et al., 2018). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine how the neighborhood laundromat might serve as an organizational broker in the community. To do so, we conducted this research within a qualitative paradigm, adopting a reflexive thematic analysis perspective (Braun & Clarke, 2021). This approach emphasizes the importance of the researcher’s subjectivity as an analytic resource in which themes are developed through a coding process that involves reflecting, questioning, and ‘dwelling with’ the data (Gough & Lyons, 2016), in contrast to finding evidence for pre-conceptualized themes.

This project was designed as a replicated single-case experiment. In this type of experiment, one unit is observed repeatedly during a certain period of time under different levels of manipulated variables. Similar to a case study, it focuses on a specific unit (e.g., in this case, a laundromat) and collects detailed data about the ecological setting. However, unlike a case study, the single-case design manipulates the environment, in this case, over two phases of design changes in the ecological setting (e.g., independent variables), to determine its effects on children’s behavior (e.g., literacy-related activity). The design provided an opportunity to gather both quantitative and qualitative information resulting from changes in the environment.

In the first phase of this study, we focus on how modest changes in the environment in the laundromat might influence children’s language and literacy activity. In the second phase, we examine the role of the local trusted messenger in creating an activity setting that supports children and their family’s engagement in language and literacy activity. This study may inform our understanding of the varieties of learning environments that might shape children’s development, and to recognize and leverage local forms of expertise that help build children’s confidence and self-identities, bridging learning opportunities across families, communities and organizations.

Specifically, our research addressed the following questions:

- What is the effect of design changes in the everyday spaces of the laundromat on children’s language and literacy-related activity?

- To what extent do trusted messengers in these transformed spaces influence children’s literacy-related activity?

- In what ways do trusted messengers engage in culturally and linguistically responsive interactions with children and broker relationships with their families?

2. Methods

2.1. Background

This research builds on two previous studies that have examined the neighborhood laundromat as an organizational broker. In previous studies (Neuman et al., 2020; Neuman & Knapczyk, 2022), we sought to understand how these ecological niches, with the addition of design features to support early language and literacy might serve as potential sources of learning for young children, helping to bridge opportunity gaps for those who lived in under-resourced communities.

The purpose of these design changes in these previous studies had been to create a space for language and literacy learning, a space that could merge the experiences and knowledge of the children and their family’s cultural traditions and language with those that are traditionally privileged in more formal learning spaces. The design features were intended to support playful experiences in which the children could make connections between their immediate personal world and activities in their larger social world of family and community. From this perspective, we viewed the space as a supportive scaffold, or, as others have described it, a ‘navigational space’ for children to understand, expand and make sense of the cultural artifacts and objects associated with literacy learning (Moje et al., 2004). Frequent visits by librarians from local branches, acting as trusted messengers, created additional opportunities for children to hear stories, and experience extension activities in efforts to connect the contents of the books with the context of the laundromat.

The results of this previous research suggested that these design features made a difference in children’s activities. Studies in three neighborhoods in New York City and ten neighborhoods in Chicago provided convergent findings that modest changes to these settings, such as the addition of literacy-related tools, toys, books, and child-sized furniture, could influence children’s behavior (Neuman et al., 2020; Neuman & Knapczyk, 2022). For example, we found that children would spend an average of 30 min engaged in literacy-related activity on their own or with others; with the addition of a trusted messenger, a public librarian, that time increased to over 47 min of activity. These findings provided convincing evidence that such everyday environments could be intentionally designed to support children’s language and literacy development.

At the same time, though highly regarded as trusted messengers, public librarians, with their extensive education and credentials, were likely to be perceived as outsiders by many in a community. In our previous studies, for example, none of them came from the neighborhoods in which they served. Their social status and position in the community seemed to set them apart from others in the laundromat including the local staff who worked there. Our observations indicated that while parents might occasionally observe children’s activities with the librarian, they rarely interacted or engaged them in conversation.

Therefore, in contrast to this approach, our goal in this study was to examine how insiders in a community, similar in racial and ethnic identity and social status, might generate learning arrangements for children and their families and to examine how such educational capital might be recognized and leveraged for broader social purposes.

2.2. Research Design

Our work reflects a growing interest in understanding how people experience activities in informal settings. The National Science Foundation (NSF), for example, has provided funding for a myriad of projects to examine the behavior and attitudes of parents and children in such natural environments as parks and recreation centers, grocery stores, and libraries. Recognizing that these settings may represent a challenge for traditional IRB offices, the Center for the Advancement of Informal Education (CAISE; informalscience.org), in cooperation with NSF, produced a series of recommendations on the ethical and practical procedures for protecting human subjects in informal settings (Gutwill, 2008). In addition to the application of the Belmont principles (1974–79) (e.g., respecting participants, limiting risks, and applying fair distribution of cost and benefits), the guidance included working with the IRB office at the local institution to determine whether this research might be eligible for exempt review or limited IRB review under the 2018 Common Rule. With these procedures in mind, prior to data collection, IRB approval was received through New York University. Given that the review provided assurances that privacy and confidentiality protections were adequate, and that the project presented no risk to the participants, we were not required to collect informed consent or debrief the participants. In accordance with the IRB guidelines, we used non-intrusive observation methods, including written field notes. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained at all times, and no personally identifiable information was collected.

Our study was designed to examine the effects of two sets of changes to the environment in the laundromats: (i) the installation of a specially designed play space by KaBoom!, a local architectural firm in Philadelphia known for creating playful environments; and (ii) the introduction of Reading Captains’ active engagement in the play space. This study took place over an 11-month period. Three laundromats in three different locations in the city volunteered for the project (see descriptions below). We used a similar research design procedure for each of the laundromats. Starting with the Big Bubbles laundromat, the first phase of this research was designed to establish a baseline of activity in the laundromat. Our focus was to understand how adults and children were likely to spend their time in a particular laundromat, the most frequent hours of operation with children, and the typical activities that occurred during their time together. Following a 2-week baseline period, in the second phase of this research, a literacy-related play area with materials was installed in the laundromat by KaBoom!, the architectural firm. During that time, we conducted observations to examine how children used their time in the area, comparing these activities to the baseline period over the next 8 weeks. Here, we were interested in how the reconfigured space might contribute to children’s literacy-related activities on their own and with others. In the third phase, over the next 8 weeks, we examined the potential value-added benefit of the trusted messengers, two volunteers from the neighborhood designated by the Global Citizen’s organization as Reading Captains. During this period, we conducted weekly observations to understand in what ways they appeared to support children’s literacy-related activities and engage with families. This research cycle was repeated for the second (e.g., Laundry Suds) and the third laundromat (e.g., 12th Street laundromat). Therefore, each cycle occurred over an 18-week period, totaling 48 weeks of observation. At the end of each cycle, we conducted a brief six-item survey of adults in the laundromat on that day to examine their beliefs about talking to their children (described below). Given the informality of the setting, our goal was to assess whether the design changes influenced language promotion activities among caregivers.

The data collection period ended with a brief focus group with Reading Captains. Together, the analysis could identify the potential effects of environmental changes on behaviors on the basis of the physical design changes alone, and the potential added influence of the trusted messengers from the community for promoting children’s early language and literacy development.

2.3. Research Setting

Our project took place in Philadelphia, the sixth largest city in the U.S. Known as a “city of neighborhoods”, it is also known as the “poorest big city in America”, with a poverty rate of over 23% that has stubbornly persisted despite years of growth and development (Cooper, 2024). Among the many initiatives to improve children’s opportunities, the William Penn Foundation funded a series of projects designed to promote literacy-enriched environments in organizations and businesses throughout the city. Based on the promising evidence from the previous studies, the Clinton Foundation’s Too Small to Fail, in partnership with Global Citizens, a non-profit organization in Philadelphia designed to advance social justice efforts through ongoing civic engagement, were awarded a grant to develop literacy-related activities in the laundromat. Leading the team, Too Small to Fail recruited three laundromats, representing three different neighborhoods in Philadelphia to participate in the project. This design allows us to observe how patrons in different demographic neighborhoods might respond to the changes in the environment and the role of trusted messengers in these different settings.

As shown in Table 1, the laundromats resided in demographically diverse neighborhoods. Laundry Suds*, for example, served families in a highly diverse, low-income neighborhood; Big Bubbles, on the other hand, largely served an African American community; and 12th Street was in a younger, working-class neighborhood.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of laundry sites.

2.4. Research Positionality

We each bring our positionality—as women who are White, middle-class of eastern European descent—to this study of neighborhood institutions in the city of Philadelphia. Having lived and worked in the communities to be studied for many years, we have seen the power of informal ties among families in poor neighborhoods in places that have ranged from branch libraries to barbershops. We undertook this project because we believed that such neighborhood institutions have often been overlooked as a source of strength and support for families, helping them to build ties to other organizations, resources and information, as well as to people that might serve their needs. In examining such local spaces as the laundromat, we have addressed this topic from an asset-based cultural perspective, hoping to learn how such neighborhood institutions create social and ecological niches for literacy learning that might engage children in symbol-using activities and take advantage of the knowledge and expertise of local people in the community.

Our research was independent of the organizations that put the materials and supports in place in these laundromats. Kaboom! the architectural firm, and the Global Citizens program, known for establishing the Greater Philadelphia Martin Luther King day of service, have deep ties to the neighborhoods, and are part of a larger consortium of programs in the Read by 4th campaign network (e.g., associated with the Campaign for Grade-level Reading). Although we were informed about their activities and the scheduling of Reading Captains in the laundromats, we had no direct contact with these organizations throughout this study. However, the first author had a much longer history of working within the consortium led by the Read by 4th campaign which might have helped to build a common understanding among the organizations and our team.

The research team (authors and research assistants) were familiar with the neighborhoods; in fact, one had lived nearby for a number of years and knew many of the local institutions. Each was instructed to make their presence known to the staff member at the laundromat, and to the Reading Captains in the second phase of this project. On the few occasions that an adult might query about their activity, they were encouraged to answer briefly, but to limit their interactions so they might observe children at play.

Our positionality certainly shaped how we viewed and examined our data. To date, a good deal of empirical research has focused on relatively simplistic categorizations of neighborhoods, seeing them in the eyes of socioeconomic status and/or racial and ethnic composition. Our work was designed to contrast this deficit orientation, to examine how families and community members may create alternative pathways of learning for their children, and the role that brokers, organizational and people, may contribute to shaping these patterns for language and literacy learning.

2.5. Procedures

Our research team included three graduate students of color from local colleges who were working toward their masters’ degrees in urban education or anthropology and lived and worked in the city. We recruited them using Handshake, a job search platform used primarily for college students at many institutions across the country to connect them with employers for internships and other career opportunities. Each graduate student had training in qualitative research through their program, and participated in a half-day observational training session with us prior to the beginning of this study. Spanish was the home language of two of the research assistants who were Hispanic; another was a native English speaker who had majored in Spanish (African American).

Prior to any design changes, the research assistants conducted baseline observations in each of the three laundromats. The purpose of the baseline observations was to understand how time was spent in each laundromat for adults as well as children. Each research assistant was assigned to visit each of the laundromats for 2 h per visit to observe activities at different hours of the week and weekend. After first mapping the physical configuration of the laundromat, they conducted frozen time checks, a momentary time sampling method to examine activity. At 15 min intervals, the research assistant would walk through the laundromat and mark where each adult and child might be standing or sitting and what they might be doing at that moment. Over the course of two weeks, the researchers observed activities for 8 h in each laundromat for a total of 24 h, marking actions by adults and older teens, and children aged 8 and under.

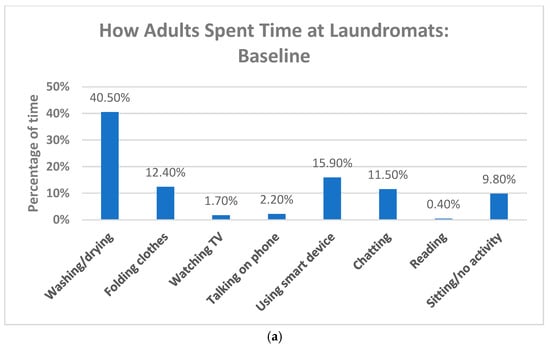

Collapsing the data across laundromats, as Figure 1a,b shows, our baseline observations indicated that adults spent time washing and folding (52.9% of actions), followed by time on their smart devices (15.9% of actions), chatting (11.5%), sitting or standing (9.8%), and ‘other’ including watching TV (1.7%), or talking on their phone (2%). There was negligible reading activity. Left to their own devices, children’s activity was primarily spent playing independently (25%), using a smart device (16%), standing or sitting (19%), among other activities. No book reading activity was observed.

Figure 1.

(a,b) Adult and children’s activity at the laundromat: baseline.

2.6. Phase 1: Design Changes

The first phase of the intervention was to transform an area in the laundromat to support children’s literacy-related play and reading activity. Partnering in this effort, Too Small to Fail first gathered input from the community to determine the themes, interests and possible changes families might like to see in the laundromat for their children. Surveying over 80 caregivers, the responses indicated their interest in colorful settings with themes that might include animals, trains, and oceans, with games and toys to amuse their children while they were busy doing laundry.

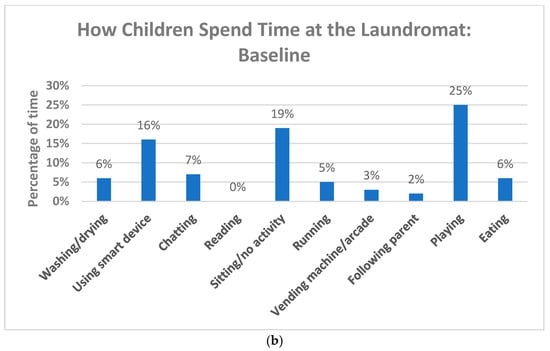

Following our baseline observations, Kaboom! installed a literacy-enriched play area based on the animal theme in Big Bubbles, the first laundromat to be transformed. Unlike our previous studies which included small-scale play areas with semi-fixed structures, their efforts were designed to use the entire laundromat as a play space. Children could build with blocks, read books about animals available in an open-faced bookshelf, play hopscotch with paw print-like letters and numbers, and find animal decals, words and alphabet letters in scavenger-like activities. The area also included signs written in Spanish and English to encourage parents to ‘talk, sing, and read’ with children (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Before and After Space Transformations.

Literacy-related activity was defined as the use of symbols in play, such as scribbling, pretend reading, and block-building to make meaning. We used this broad characterization of literacy to reflect the many ways children begin to represent experiences—capacities they will draw on when they begin to formally interpret decontextualized print. Conversations with adults, playing with toys, letters, and puppets, as well as listening to stories, flipping pages in a book, and drawing may constitute young children’s early symbol-using activities and highlight the many pathways to literacy learning. In this respect, our characterization of literacy was designed to expand beyond what is traditionally valued in early literacy instruction in school, creating a space where children could find ways to make meaning long before they can formally read and write.

Once the design changes were in place, the research assistant conducted two-hour weekly observations of children’s activity in the laundromat. Adapting a protocol from our previous studies, we developed a time-use diary that identified: (i) who played in the setting or in the literacy-related areas in the laundromat (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity), (ii) what they did in the setting (e.g., reading, block playing, etc.), and (iii) their interactions with adults. Each ‘instance,’ defined as a literacy-related unit of action (e.g., reading, writing), was counted. For example, the child might read for a few minutes, then play with blocks, then return to book reading, indicating three instances of literacy-related activity, two of which were book reading. Within each time block, we took low-inference notes, describing what was taking place without drawing conclusions (e.g., Engage NYC).

Conversations with an adult (e.g., parent or caregiver) in the play setting were coded as they occurred in real-time using an adapted version of the codebook (e.g., Promoting Communication (PC) Talk) developed by Walker and her team (Walker & Bigelow, 2020) and known to support child language outcomes. Specific to our research, the research assistants used a checklist marking the presence of a language promotion activity if the adult: (i) labeled objects or things for the child (Ricciuti et al., 2006); (ii) asked an open-ended question (Whitehurst et al., 1994), and (iii) engaged in a conversation (e.g., identified as two discrete utterances between a child and adult dyad (Gilkerson et al., 2017). In the first week, two research assistants were assigned to the laundromat, and used the checklist independently during a day’s activity to establish reliability. Cohen’s Kappa indicated 0.90 on coded variables, occasionally mis-estimating the child’s age. Low-inference notes were also reviewed by the project manager, identifying specific language to determine agreement on coders’ assignments of talk strategies. Once reliability was established, the research assistants individually observed activity for an 8-week period, totaling 16 h of observation in the laundromat.

2.7. Phase 2: Enter the Trusted Messenger

Following the Phase 1 observation period, Phase 2 introduced the trusted messengers in the laundromat. Launched in 2017, the Reading Captain program was designed to help local families connect to resources and organizations to support their children. Established by the Read by 4th campaign and trained through the Global Citizens’ nonprofit organization, the Reading Captain program is a voluntary organization of adults who are interested and committed to helping their neighbors raise strong readers. Volunteers must be over the age of 18, already connected to families in their neighborhood and around Philadelphia, and committed to working in their community and collaboratively with partners citywide. The volunteers received training in trauma-informed practices and early literacy, and participated in periodic virtual meetings with the nonprofit. The program developers describe them as similar to a block caption, but for “all things early literacy”. Other than being an adult resident in the neighborhood, there were no particular requirements or hours specified for the position.

Recognizing that families often turn to their friends and neighbors for important information and guidance, the goal of the program is to help families learn about the literacy resources available to them, and to share information resources in places where their neighbors are likely to go such as the grocery store, barbershop, and laundromat. As one Reading Captain put it, “Who knows the neighborhood better than someone who lives on that block?”

Six Reading Captains, in total, participated in this project (five female; one male). Three were Hispanic; two were African American; one was White (average age: females over 60; male, 40 years old). Based on the demographics of the neighborhood, two Reading Captains were assigned by Global Citizens to each laundromat to read and engage with families in two-hour weekly visits for the next eight weeks. Both were from the immediate neighborhood; in the first laundromat for example, one was Hispanic, and the other was African American. Under the larger umbrella of playful learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009), their task was to engage children in activities such as book reading and play, and to act as an information resource to families about early literacy.

The Reading Captains began their visit by inviting the children who might be wandering around the laundromat to read some books and play games. They might gather in the literacy area, away from the machines, read and engage them in conversations, and draw pictures together. Other times, they might chat with staff and family members about neighborhood events, and activities at the local library, making parents aware of services and what was available for free. Their visits, however, were unscripted, and spontaneous. If a parent was too busy to talk, or the child was too shy to play, the Reading Captains might just wander off to talk with staff or other families. For example, they might talk to one parent about kindergarten registration, to another, about activities at the local school. As one Reading Captain put it, their role was to be a “Captain Americas of reading” by connecting with children and families. “We’re ‘engagers.’ We build relationships. It’s going to take the whole village to get our kids where they need to be”.

During the next 8 weeks, the research assistant observed the Reading Captains’ interactions with children, and families using the same checklist as in Phase 1. We also continued to engage in low-inference note-taking, delineating the context of the activity and what the Reading Captain and children might be saying and doing in the activity setting. In total, we observed 16 h of activity in the treatment setting. In this respect, we could determine how each design phase compared to one another.

This cycle of activity occurred in two more cycles of data collection; for example, following baseline, the Laundry Suds environment was enhanced with literacy-related materials in Phase 1 for 8 weeks; in Phase 2, the environment was further supported by two Reading Captains, both African American from the neighborhood for 8 weeks. A similar cycle occurred for the 12th Street laundromat. Together, 96 h of observation occurred across these three laundromats.

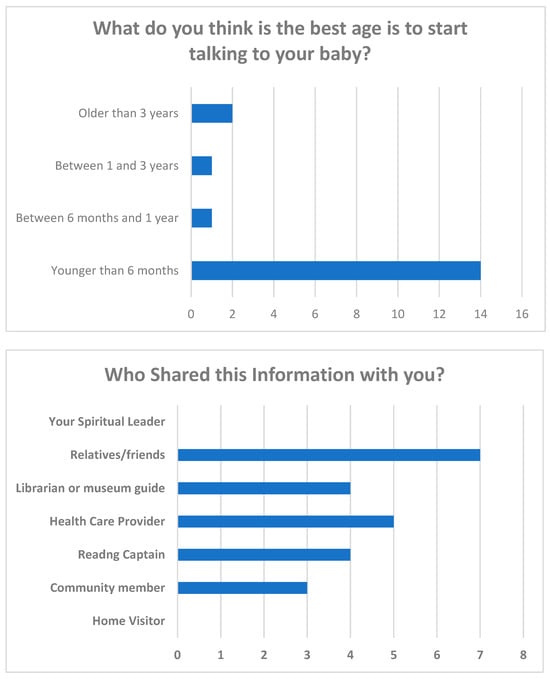

Toward the end of the project, we visited each laundromat for a final time and gave a brief 6-item survey from the Child-Family Information survey (Child-Family Information Survey, NIH) to caregivers with children who were doing laundry on a particular weekend day. The items asked caregivers: (1) whether they were a resident of the local community; (2) the child’s age; (3) whether anyone in their family and community ever communicated about the importance of talking with their child; (4) who shared the information; (5) what the best age might be to start talking to their baby; and (6) who shared the information with them, adding the option of Reading Captain among the items. Twenty-two caregivers responded to the survey across the three laundromats at the end of the Phase 2 observational period.

Following the conclusion of this project, we held a brief, informal conversation with all six Reading Captains to understand how they saw their role in the project. The conversation was held on zoom, and recorded with their permission.

2.8. Analysis

Our analysis was based on the activities in the sites and not on the individual children. We collapsed the data from individual sites in two categories: observations of activities as a result of the environmental changes alone in Phase 1, and observations with Reading Captains in Phase 2. All data were transferred to excel files. We counted the number of instances and the type of play within each observation of literacy-related activity. For example, a child might spend 20 s flipping through a book, 5 min drawing a picture, and 10 min building with blocks during the time in the center. This would be counted as three instances of literacy-related activity noted by the type of activity and the time devoted to it.

To analyze the data, we calculated the percentage of time spent and the type of children’s activity across sites. We then examined the social communication features in these activity settings using information from the checklist, focusing on labeling (e.g., “I am sorting by color. This one is green”), open-ended questioning (e.g., “if you were this animal, what would you do?”) and conversational turn-taking (e.g., two or more turns), all of which are known to support gains in language development (Gilkerson et al., 2017; Ricciuti et al., 2006; Romeo et al., 2018; Whitehurst et al., 1988). Together, these data provided quantitative information on changes in children’s activities as a result of the design changes alone, and the additional supports of the trusted messengers in the settings.

Finally, we conducted a qualitative analysis, focusing on how Reading Captains engaged in these discourse practices with children and families, and the cultural and linguistic features of their interactions. To conduct this qualitative analysis, we first reviewed the research literature to identify strategies that appeared to promote language and literacy development for children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. This research highlighted the benefit of labeling, conversational turns, and responsive interactions in children’s home language (Gilkerson et al., 2017; Romeo et al., 2018). For example, studies have shown that programs that promote the continued use of children’s native language in addition to English best support language development for dual language learners (Hammer et al., 2009). Adults and children may incorporate translanguaging, or multiple discursive practices to make meaning, in contrast to a strict separation of languages (e.g., English or Spanish) (Flores, 2019; Garcia, 2009). Translanguaging allows individuals to draw from their full linguistic repertoire, blending languages fluidly to enhance communication and understanding. This approach challenges traditional language boundaries and promotes inclusivity by acknowledging the richness of bilingual or multilingual experiences. It fosters a more supportive learning environment and helps bridge the gap between students’ lived experiences and formal educational settings. Similarly, studies have shown the importance of respecting children’s home language by taking full advantage of children’s oral language repertoires, and their dialectal variations, which might differ from the more general versions of standard English used in school (Washington et al., 2018). Programs that incorporate children’s own life experiences, reflective of their group membership, have been identified as a culturally responsive practice (Griner & Stewart, 2013). From this literature, we developed an initial set of strategies that might reflect the interactions we observed in these settings.

We then transferred all low-inferences notes to the MAXQDA qualitative software. To analyze the data, we applied Braun and Clarke’s theoretical thematic analysis framework to our dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This approach tends to be driven by researchers’ theoretical interest, and is more explicitly focused on a detailed analysis of some aspect of the data related to a research question. We sought to identify cultural and linguistic features of interactions on a semantic level within the explicit behaviors and actions of the participants.

Following their analytic framework, in the first step, the research team (the authors, and a graduate research assistant) independently read and re-read notes, using the highlighting features of the software to capture features in Reading Captains’ interactions with children and families. At this point, our goal was to code interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the dataset using open coding, and to collect examples relevant to each code. In the next phase of the analysis, we then reviewed our notes, comparing what we were finding with the strategies identified from the literature. We identified examples of interactions that reflected a particular strategy. For example, a Reading Captain’s use of translanguaging was an example of successful interventions that encouraged the use of the native language alongside English (Garcia & Wei, 2014). In so doing, our goal was to try and capture the instructional features of these interactions across these informal settings.

However, our analysis was not a linear process of simply moving from one phase to the next. Instead, it was a more recursive process, where movement went back and forth as needed. As we reviewed and refined our categories, we examined additional examples, keeping in mind Patton’s dual criteria of coherence within theme and distinctions between them (Patton, 1990). In the final process, we reduced our original categories to several key themes, keeping in mind that the ‘keyness’ of a theme according to Braun and Clarke (p. 92) was not to be defined in any quantifiable terms, but on whether it captured something distinctive in relation to the overall research question.

We used several procedures to examine the credibility and trustworthiness of our interpretations (Nowell et al., 2017). We held several debriefings with organizations (e.g., Too Small to Fail; Read by 4th) who were familiar with the project, but not directly involved in it as an external check on our interpretations. Read by 4th, for example, had worked extensively in communities, establishing the role of block captains for family support in selected neighborhoods. They provided validation, indicating that the themes resonated with their perspectives as well as useful feedback to our preliminary findings. We also engaged in member-checking, asking three of the Reading Captains to review our themes and to check for the authenticity of our interpretations. Their verbal feedback in an open forum gave us further validation on the accuracy of our analysis. Finally, we presented our themes with examples to a working outside group, collectively known as the Literacy-enriched Environment Community of Practice funded by the William Penn Foundation, all of whom were highly familiar with the research being explored. They provide verbal confirmations from their research in the communities, adding further credibility to this research.

3. Results

In the following results, we first examine children’s activities in the laundromat as a result of the changes in the environment alone, specifically the addition of literacy-related materials. We then broaden our lens to understand how Reading Captains might influence the types of interactions and behaviors of children in these activity settings. Lastly, we focus on the qualitative features of these interactions, highlighting the ways in which these community volunteers appeared to build connections with children and their families through culturally and linguistically responsive talk grounded in the daily activities of their neighborhood.

3.1. Effects of Design Changes in the Laundromat

Table 2 describes children’s activities before, and after the changes to the environment. Prior to the changes, the children seemed to engage in activities that mirrored those of the frozen time checks. They spent time playing on their own, but otherwise spent time sitting quietly, often using their smart devices or chatting, running, eating, or sometimes using the vending machine. There were no print-related activities visible to research assistants recorded in these observations.

Table 2.

Children’s activities before and after the space transformation in the laundromat: Phase 1.

Once the materials were in place, however, children spent more time playing on their own and with others in the laundromat space. They spent time playing with blocks, and some time on reading, though without an adult to guide them, much of that time was ‘flipping.’ This was a term to describe brief episodes of picking up a book, thumbing through the pages for a minute or two, and putting it down.

Nevertheless, overall, there was limited evidence of much literacy-related activity other than the modest changes in drawing/writing and book flipping in the play areas. Rather, the environmental changes alone did not appear to generate many additional opportunities for children to engage in tasks or talk related to early literacy.

3.2. Effects of the Involvement of Reading Captains in the Laundromat

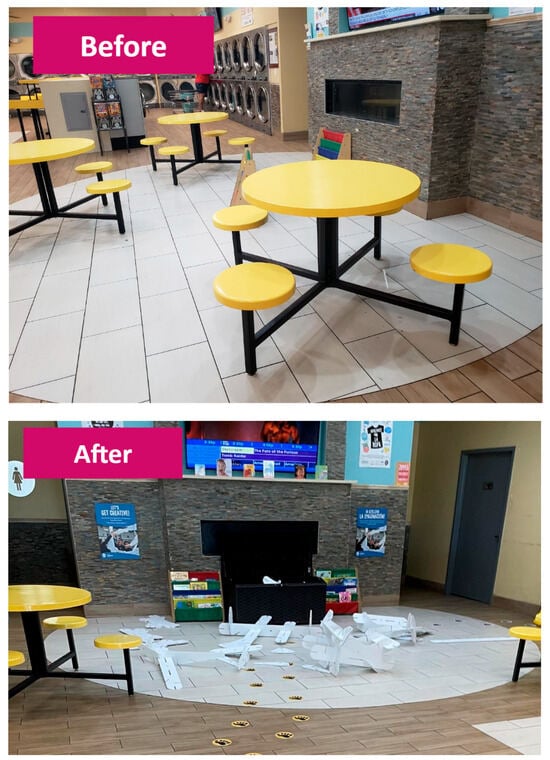

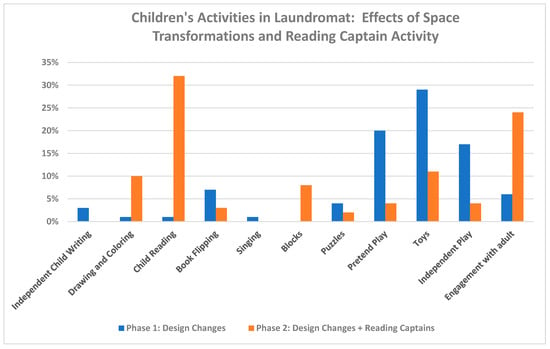

These sociocultural environments, however, were about to change with the involvement of the Reading Captains. Figure 3 describes the changes in activities resulting from these weekly visits. Most striking were the differences in the amount of time spent reading with children. On average, the Reading Captains read four books to children per visit with book flipping reduced, and spent more time drawing, writing, and playing with blocks. As a result, children spent less time on independent activities than in the prior phase of the intervention.

Figure 3.

Comparing children’s engagement in literacy resulting from space transformations and Reading Captains’ activity.

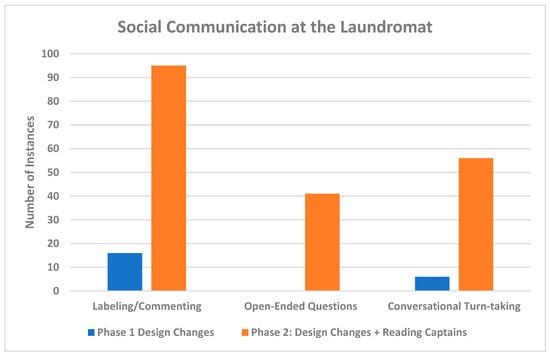

The Reading Captains’ participation affected the language environment in these settings. Figure 4 describes the social communication patterns following the changes to the environment compared to the times when Reading Captains were present. As Figure shows, talk increased substantially during their visits, as shown in the instances of labeling, open-ended questioning and conversational turn-taking.

Figure 4.

Comparing children’s engagement in talk resulting from space transformations and Reading Captains’ activity.

The context of book reading seemed to generate many of these interactions. In the course of reading books, for example, Reading Captains would engage children in conversations, introducing new words, such as “This is called a weathervane. It helps us to tell the weather”, asking open-ended questions such as “What’s the weather like in this picture, do you think?” and turn-taking conversations, like the following:

After reading a page, RC1 points at the illustration. “Do you know what that is?”

- Child #1: Corn!

- RC1: Do you like to eat corn?

- Child #1: Yes

- RC1: You like it with chili? And queso? (she motions as though she is eating)

- Child #1: Yes, I like corn with cheese.

- RC1: Me too!

Yet, as the figure also shows, there were times when children and the Reading Captains would choose to spend time together, striking up conversations informally apart from any particular activity. They might play with blocks or toys, or just spend time talking together. In addition, in between various cycles of laundry, parents might stop to chat with the Reading Captains. The informality of these conversations seemed to convey a ‘comfort level’ that we had not seen in previous studies (Neuman et al., 2020; Neuman & Knapczyk, 2022). As shown in Figure 4, the Reading Captains’ process of sharing experiences, knowledge and understandings appeared to support a number of culturally and linguistically responsive language-promoting strategies with children while building trust with families in these communities of color.

3.3. Ways in Which Trusted Messengers Engaged in Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Interactions

Our qualitative analysis revealed four inter-related features in Reading Captains’ conversations with children and parents that seemed to support their participation. Table 3 describes these features and provides a brief example.

Table 3.

Trusted messengers’ culturally and linguistically responsive talk strategies.

The first feature was the Reading Captain’s use of the children’s native language, Spanish, alongside their use of English. As they engaged with children, they would often weave various phrases in conversations in both languages in a way that seemed natural and fluid, supporting children’s use of their full linguistic repertoires. For example:

A 4-year-old is unwrapping her new school supplies. “What is this?”, she asks the Reading Captain, holding up a pen.

- RC: Es un boligrafo

- Child: [Holding a ruler]. What’s this?

- RC: A ruler-la regla. We use it to measure how big things are. Do you measure in 4 inches or in centimeters?

- Child: [Doesn’t answer, but uses her finger to count each centimeter]. “Eleven”

- RC: That’s right 11 cm!

- Child: [Now holding a pack of erasers from her bag]. “Y borradorres”

- RC: Yes, erasersa

Reading Captains would often begin their conversations by asking children their language preference. Sometimes a child would answer; sometimes, not. In one case, for example, the Reading Captain asked a child, “Let’s go find some books; vamos a buscar los libros”. The child did not respond, but shyly put her hands on a book. In response, the Reading Captain said, “This is just in English. Do you want me to do a translation in Spanish?” The child nods yes.

Speaking their native language, Reading Captains frequently approached parents to offer guidance about activities in the city and available resources. For example, a 35-year-old Hispanic parent is looking over the materials on the book shelf, when the Reading Captain comes over and greets her in Spanish, telling her more about the activities with children in the laundromat. They start a conversation about the Reading Captain’s work with immigrant families, and soon it reminds one of a coffee klatch as they chat at the table while building blocks with the children. After a while, the mother returns to her laundry with the Reading Captain’s contact information in hand, along with a book for her child.

The second feature, related to the first, addressed the issue of resources in these spaces. There was a deliberate attempt to include signs, materials, and book selections that represented the populations that visited the laundromat and local relevance. For example, throughout the laundromat, signs and game activities were in Spanish and English. Book selections included stories and pictures about Philadelphia, some even by local authors. Games engaged children in culturally related activities. During one observation, for example, the Reading Captain and children start singing the alphabet song. She then hands out macarenas, and they start to sing the ABC’s again, giggling while they try to keep the beat with the macarenas. Another time she chooses a book called “Guacamole” written primarily in English with some Spanish words. “This is a cooking book about making guacamole. You like to cook?” The children then draw their own guacamoles (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Reading Captains’ Activities.

The Reading Captains used their understanding of the life experiences of families in the neighborhood to make connections with the children and parents, the third culturally and linguistically responsive feature. They seemed at ease in approaching people, in this case, a young 20-year-old Latine male, who seems to be spending time during the day at the laundromat. She opens by asking him if he is in school, and what he likes to study, and learns in the course of conversation that he finds math interesting but needs to take care of a couple of siblings. She then mentions the educational support work she’s engaged in with students his age, and how she helps families access services. He seems interested and takes her contact information before he leaves. At another time, the Reading Captain approaches a parent, hoping to read to his child. They discuss the problem of violence in the city, and their fear of bringing children in and around the city. Living in the same context, she seems to convey a joint cultural understanding of the complexities of raising children in the city, creating a common bound with the parent that prompted an ongoing conversation.

Throughout our observations, Reading Captains frequently gave their contact information to families. Without any specific prompting, they might walk up to families, strike up a conversation, and depending on the topic, encourage them to reach out if they needed help. “Food, clothes, health care, community services or any service, whatever you need, I’m here to help”, say one RC. At times, they might offer a free book to the children or toys or even money for the vending machine. When the observer asked about these instances, the Reading Captain replied, “These families need additional support. The schools can’t do it 100%. No one is going to say anything negative to these children. A lot of classrooms have negativity. I work on the children’s self-esteem”.

Relatedly, the fourth feature seemed to build on their understanding of a shared group membership, and cultural understanding of the community to create ties within and across other institutions. They knew their city, and a result, could help families navigate complicated waters. As one RC put it, “We’re not only talking with parents, we’re pulling together other resources within the community. We’re bringing them all together. We have something for everyone”. For example, some parents were unaware about kindergarten registration, as one RC recalled:

Striking up a conversation with a father, she asks:

- RC: How old is your child?

- Father: He’s 4-year’s old.

- RC: Is he in school?

- Father: I’m getting him ready to start school next year

- RC: Is he enrolled in kindergarten?

- Father: I’m not sure what you mean.

- RC: In Philadelphia, you need to enroll your child right now in kindergarten. They’re only so many slots for the kids in the city. I’ll show you the place to register [gets out her phone to show him].

Other times, the Reading Captains would hand out library registration forms, special story hours, clothing drives, bulletins about where to obtain free mammograms, building connections to other resources in the community. In this respect, they used the laundromat as an organizational broker to provide families with information on access to an array of resources from other external institutions. They seemed to understand that families were “not only struggling with reading but other things as well”, and sought to show how different community organizations and institutions may come to their support in raising their children and ensuring their well-being. Together, these culturally and linguistically responsive features in Reading Captains’ interactions with children and families appeared to create communication patterns that were empathetic, respectful, and practical, adding to their credibility as trusted messengers in their community.

Supporting this thesis, as shown in Figure 6, our survey revealed that Reading Captains were among the individuals most recognized as information providers in the community. Although family and friends topped the list, caregivers reportedly relied on health care providers, librarians, and Reading Captains for information on child development. These results suggest that over a relatively brief time period, these individuals seemed to know how to connect to their audience, conveying knowledge and values central to child development and, in its course, becoming resource brokers that may influence family life in (Milner, 2020) communities.

Figure 6.

Survey results of caregivers in the laundromat.

4. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to understand the role of the laundromat as an organizational broker in a community, and how everyday spaces in these activity settings might influence children’s language and literacy activities. It builds on the research showing how neighborhood institutions like hair salons, barbershops and childcare centers may connect people to other people and to other organizations and their resources. Studies (Small, 2006, 2009) have shown how crucial these institutions may be in promoting social ties and for accessing information and resources, particularly for those living in poor and immigrant communities where structural inequalities and discriminatory practices have severely limited learning opportunities. In communities where resources are often channeled through a maze of complex bureaucracy, these institutions may serve as critical bridges, providing access to services that would otherwise be unattainable.

In this study, the physical space within the neighborhood laundromat seemed to act as a passive organizational broker, a space for the exchange of information, resources, social interaction and networking. It provided opportunities for young children with support from trusted messengers in their community to engage in literacy-related play, and for families to interact with others in informal interactions that mapped on to their local interests and cultural histories.

4.1. Creating a Space for Literacy Learning

Resources and materials were integrated with literacy-learning opportunities to create a space grounded in children’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds. It was designed to expand beyond the traditional boundaries of literacy as simply decoding and encoding print to include pretending to read, drawing and scribbling, and playing with puppets among other symbolic activities. In these spaces, children crafted opportunities and resources for constructing and communicating meaning with their peers and trusted messengers. This suggests that these intentionally designed, community-based spaces can help build experiences that serve as bridges to early literacy learning.

These activity settings were created through a community-informed process that sought to engage local customers in design concepts. The survey results were used by the designers to create a space in the laundromat based loosely on a particular theme, with books, blocks and some toys to involve young children in playful learning. In the first phase of this study after the initial baseline, our aim was to understand how time was used in these settings and the social interaction patterns that children might engage in with other children and adults. Our results found modest changes in children’s activities with increases in playing with toys, drawing, and writing, and book reading (though mostly book flipping), and decreases in non-intentional play (running around), viewing of a mobile device, and sitting.

The role of the trusted messenger. This pattern of activity was changed dramatically with the involvement of the Reading Captains, local volunteers from the neighborhood. Book reading often provided the resource for communication patterns that supported labeling, open-ended questioning, and conversational turns with children, rising sharply in comparison to these patterns during the design phase alone. An analysis of these conversations highlighted the Reading Captain’s ability to create intersubjective ties with children and their families that were sensitive to the cultural and linguistic context of their neighborhood. Their use of translanguaging, ability to adapt materials and resources to support children’s strengths and interests, their knowledge of the city, both its challenges for raising children and well as its assets, specifically the organizations and resources designed to help, seemed to endear them to the people they were there to serve. They became trusted messengers in their community.

Studies of social impact campaigns have long recognized the power of trusted messengers in delivering information and countering misconceptions and fake news. As one research team put it, “A message is only as effective as the person who delivers it” (Wright et al., 2021, p. 2). However, what makes these messengers become trusted is far less well understood. Health-related campaigns, for example, have found that the closer a messenger is to a person, the more they are likely to trust them in understanding issues (Metzger et al., 2010). Our brief survey confirmed this finding, indicating that caregivers were most likely to go to friends and relatives for information and advice. In addition, during the recent pandemic, the CDC found that messages were often better received if the messenger was of a similar race or ethnic group, or in a similar situation as their intended audience. Doors were more likely to be opened to their neighbors than for someone outside the neighborhood. The Reading Captains seemed to understand this; as one put it, “You see each other every day; you’re walking in the same grocery stores—children go to school around the corner. They look at us as part of their family. They trust us. They are more receptive to us rather than someone coming in from outside. It’s a warmer climate”.

In addition to their familiarity with the context, these individuals engaged in culturally and linguistically responsive communication patterns that have been shown to make learning encounters more relevant and effective. Their use of these asset-based practices positioned children’s language, culture, and identities as resources and shaped these learning opportunities, providing a foundation for establishing a relationship with children and their families. These findings are convergent with a recent meta-analysis (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), indicating that feeling good about one’s ethnic and racial identity is inextricably related to positive adjustment and learning, with studies reporting small to medium effect sizes (0.11 to 0.37). Therefore, incorporating these culturally sustaining practices may represent essential competencies in identifying or becoming a trusted messenger.

Different roles of trusted messengers. Our findings also suggested that trusted messengers may play different roles in these everyday spaces. For example, in two prior studies, children’s public librarians took on the role of trusted messengers, spending the majority of their time engaging children in informal literacy-related activities that included book reading, singing, writing, and puppetry (Neuman et al., 2020; Neuman & Knapczyk, 2022). Children’s involvement in these literacy-related activities soared, spending an average 47 min of activity in the setting. Yet, there was minimal interaction with parents or caregivers. In contrast, trusted messengers in this project seemed to approach their role more broadly, developing relationships between children and their caregivers in activities related to reading and to other services that families might need. Although they read frequently to the children, they appeared to spend an almost equal time talking with children and trying to connect with families in a myriad of ways. In this respect, the emphasis was less on teaching, and more on relationship-building with children and their families.

This is not to suggest a preference for one approach over another. Children undoubtedly will need readiness skills and knowledge to become highly capable readers. Yet, it does suggest that children will need to build these readiness skills along with a variety of other personal and social assets as well. Studies have documented that social–emotional skills are linked to language and literacy outcomes concurrently and longitudinally (Skibbe et al., 2011). In this study, children received implicit confirmation that their language and social practices were not just accepted but valued by others. Therefore, a broader, more holistic view of helping our young children reach their full potential is gaining wider credence in policy and practice. In these everyday spaces, children are likely to engage with caring adults inside and outside their families, and in the course of these relationships, develop a sense of security and personal identity needed to become successful thinkers and learners.

Materials and resources in everyday spaces. To complement this work, we will need further research that can inform the design of these everyday spaces. For example, space transformations in this study resulted in only modest changes in literacy-related activities compared to the sizable gains in previous studies. In a study conducted in three neighborhoods in NYC, children in laundromats outfitted with literacy-related play centers engaged in 30 times more literacy activities than did children in laundromats that did not have such resources (Neuman et al., 2020). In contrast to the small play centers configured in this previous research, the designers of this study attempted to use the full laundromat as a play setting with themes that had little relation to the setting itself (e.g., wild animals; oceans). Studies of playful learning, however, have shown that smaller spaces with semi-fixed structures, as opposed to wide expanses, provide more opportunities for social interaction (Roskos & Christie, 2007). Further, aggregating collections of materials and objects in familiar and relatable themes (e.g., dramatic play) is known to sustain conversational interactions in play (Neuman & Roskos, 1993). Therefore, integrating design features in literacy-related play along with community input might promote more language-enriching activities in these everyday spaces.

4.2. Limitations

We recognize that there are limitations in this research. First, although we have argued that neighborhood institutions like the laundromat can serve as an organizational broker, not all may serve in this capacity. Importantly, policy mandates, outside funders or larger organizations might play a role in the brokerage process, compromising the institution’s ability to serve as sites that reflect community interests, and social interaction. Coercive pressures from more powerful authority mandates may hold sway, creating an environment hostile to the brokering of resources, and its crucial role in disrupting inequality (Baldridge et al., 2017). Consequently, much work remains to be conducted to determine which neighborhood institutions are likely to operate as organizational resource brokers.

Second, we recognize that the relative novelty of this setting and its pedagogical approach presents a number of methodological challenges in studying how language and literacy-related activity occurs in this everyday setting. Given the nature of informal learning and the public space in which it occurred, it was impossible to focus on the individual child level; rather, we needed to focus on the context and how children interacted with others and reacted to that context. In addition, due to institutional review board restrictions, no recording devices were used. Instead, we conducted rapid ethnographic techniques (Sangaramoorthy & Kroeger, 2020), including observation and low-inference note-taking, and photographic analysis (e.g., areas and placement of materials), in addition to brief surveys, and conversations with families and Reading Captains.

Third, we also acknowledge that this project involved only three treatment sites. Yet, these laundromats served neighborhoods that were diverse in racial composition, size, and population density (5187–17,550 people per square mile), providing a fair representation of life in urban communities. In addition, we recognize that our findings cannot generalize to other communities or settings or that the Reading Captains in this project might be representative of trusted messengers in other neighborhoods. At the same time, we can suggest that the communication patterns reported in this project may serve as important exemplars for volunteers who may wish to become trusted messengers.

With these limitations in mind, our study highlights the role that a neighborhood institution might play as an organizational broker in creating an everyday space for more equitable opportunities for children’s language and literacy learning. It suggests that everyday spaces can serve as cultural niches that become important sites for learning. It also shows how the expertise of local citizens can be leveraged to generate powerful learning opportunities that foreground language and literacy learning as a cultural practice. In this respect, it expands our understanding of the social and relational practices that may constitute early literacy learning and the opportunities for participation and new experiences that these spaces may provide. Moreover, it is likely to offer additional pathways for literacy learning beyond the institutional walls.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.N.; Formal analysis, L.K.; Data curation, S.B.N. and L.K.; Writing—original draft, S.B.N.; Writing—review & editing, S.B.N.; Visualization, L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding