Abstract

Student participation in educational decision making, for example, through data-informed decision making, can have a positive effect on student well-being, engagement, and performance. Teachers play a crucial role in student participation, and leadership is a main factor influencing teacher professional development, which can lead to improved experiences and outcomes for students. In this study, we aimed to combine the benefits associated with data-informed decision making with those associated with Professional Learning Communities. Moreover, we included students as PLC participants. This study therefore focuses on the question how school leaders can support teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs. Based on previous research, we used leadership core functions needed for successful PLCs to describe school leaders’ roles in an approach to student participation that combines the pedagogical analysis model and Shier’s model for student participation. School leaders and teachers from five schools participating in the previous study were interviewed to describe school leaders’ roles. The findings show what concrete school leader activities can support teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs and what implications this has for practice, policy, and further research.

1. Introduction

Student well-being, engagement, and performance are increasingly at stake internationally (Meelissen et al., 2023; Rinnooy Kan et al., 2023). Student participation in educational decision making, for example, through data-informed decision making, can have a positive effect on student well-being, engagement, and performance (Jimerson et al., 2016; Mitra, 2004; Yonezawa & Jones, 2007). Data-informed decision making, or data use, is considered a key strategy to support instructional improvement and student achievement. Data use concerns teachers and school leaders systematically collecting and analyzing different types of data to guide decisions to help improve the success of students and schools (Datnow & Hubbard, 2016; Mandinach & Jimerson, 2016; Marsh & Farrell, 2015). Active student participation can help educators better understand and address the problems that schools are facing (Mitra, 2004; Yonezawa & Jones, 2007) because students may have a different perspective on certain problems. This can help educators to improve the school for all students (Fielding, 2001; Yonezawa & Jones, 2007). Moreover, students’ involvement in data use can contribute to developing data literacy among students, which is an important skill in our society (Gebre, 2018; OECD, 2019). Ministries of Education and national education policy organizations have also emphasized the importance of student participation (Dutch Secondary Education Council, 2021; Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, 2017).

Teachers play a crucial role in student participation, while leadership is a main factor influencing teacher professional development, in general (V. M. Robinson, 2010), and data use specifically (Anderson et al., 2010; Marsh & Farrell, 2015), which can lead to improved experiences and outcomes for students (V. Robinson et al., 2008). Specifically, leadership is important for student–teacher partnerships, given the related shift in power relations accompanying these partnerships (Strijbos & Engels, 2023). School leadership has been studied extensively regarding impact on teaching practice and student performance (e.g., Hendriks & Scheerens, 2013; V. Robinson et al., 2008; V. Robinson & Gray, 2019) but not often in relation to student participation. To go beyond the rhetoric and let students feel that teachers and school leaders truly value student participation, greater clarity is needed on what achieving student participation means in practice and how leadership can support that (Holquist et al., 2023). Therefore, in this paper, we focus on the role of school leadership in connection with student participation.

In this study, we aimed to combine the benefits associated with data use (e.g., Ansyari et al., 2020; Grabarek & Kallemeyn, 2020; Lai & McNaughton, 2016; Van Geel et al., 2016; Van der Scheer & Visscher, 2018) with those associated with PLCs (e.g., Poortman et al., 2022; Wennergren & Blossing, 2017). According to Stoll et al. (2006), professional learning communities are groups of teachers (and possibly school leaders) who share and critically interrogate their educational practice in an ongoing, reflective, collaborative, and learning-oriented way. In this study, we expand the PLC participant group to that of students.

While school leader core practices (Leithwood et al., 2020) are crucial for school improvement, the ways in which these are adapted to specific contexts is key (van den Boom-Muilenburg et al., 2022). The current study focuses on the core leadership practices that are needed in connection with active student participation in data-informed decision making. This study’s main question is the following: how can school leaders support teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Student Participation

Student participation has been elaborated in different models, such as Hart’s (1992) ladder and Shier’s (2001) pathways. In this study, we conceptualized student participation according to Shier (2001). While Hart’s ladder of participation was very influential in the field, Shier builds on Hart’s ladder, recognizing how the adults involved have different degrees of commitment to student empowerment (Shier, 2019) (see Table 1) with five levels of student participation. Teachers’ and school leaders’ level of commitment at each level of participation can be different. The question is not only whether staff are ready to listen to children, support them in expressing their views, and so forth (openings) but also whether procedures are available to really make this happen (opportunities) and whether it is a policy requirement (obligations). Being ready, having procedures available, and having policy requirements at each level of participation are three stages of commitment needed for successful student participation, according to Shier (2001).

Table 1.

Pathways to participation (adapted from Shier, 2001, p. 111).

Shier (2001) identified five possible levels of student participation:

- Children are listened to, as shown in the way of working and policy of the school.

- Children are supported in expressing their views, both in the availability of a range of activities to help children express their views and in the school’s policy requirements.

- Children’s views are taken into account in the decision-making process in the school, and the school has a policy requirement that the children’s views must be given proper weight in decision making.

- Children are involved in decision-making processes in the school, as acknowledged in both procedures and policy.

- Children share power and responsibility for decision making in the school, in terms of both policy requirements and procedures to enable children and adults to share power and responsibility.

2.2. Leadership for Student Participation in Data Use

Several systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses addressing successful school leadership are available (Leithwood et al., 2008, 2020; V. Robinson et al., 2008). These reviews show, for example, that leadership significantly influences school organization features and, consequently, the quality of teaching and learning (Leithwood et al., 2020). As demonstrated in these reviews, almost all successful leaders draw on distinctive leadership practices, such as setting directions, building relationships, developing people, redesigning the organization, and improving the instructional programme (Leithwood et al., 2020). Previous studies about the role of school leadership for successful PLCs have used leaders’ core functions to describe their role in relation to educational improvement (Bryk et al., 2010; Leithwood, 2021; V. Robinson et al., 2008). The leadership practice of setting directions, for example, refers to building a shared vision and communicating the vision and goals. In the current study, which focuses on leadership that is required for supporting teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs, we used leaders’ core functions as described by van den Boom-Muilenburg et al. (2022). These authors summarized the core leadership functions needed for successful PLCs (also data-use PLCs), also based on previous research (e.g., Forfang & Paulsen, 2021; Leithwood et al., 2020): (1) organizing and (re)designing the organization, (2) managing the teaching and learning plan, and (3) understanding people and supporting their development.

The first core function, related to organizing and (re)designing the organization, concerns a clear vision for data use (including goals and expectations; Schildkamp et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2016; Leithwood et al., 2020) and student participation, along with making these a priority (Brown & Flood, 2020) and creating coherence between student participation in data use at the school and the school organization (van den Boom-Muilenburg et al., 2022). The second core function of managing the teaching and learning plan refers to planning, monitoring, and evaluation, in this case with reference to student participation in data use. The leadership practices in this core function have the most direct effects on students because they directly shape the nature and quality of instruction in classrooms (Leithwood et al., 2010). The third core function about understanding people and supporting their development refers to providing support, being available and accessible, and being able to support connections and building trust to improve education. This also concerns being a role model (for student participation in data use) as a leader and being knowledgeable about this, as well as sharing knowledge (van den Boom-Muilenburg et al., 2022).

3. PA-Model Intervention in This Study

3.1. Collaboration in Data-Informed Decision Making by Students, Teachers, and School Leaders in the PA-Model Intervention

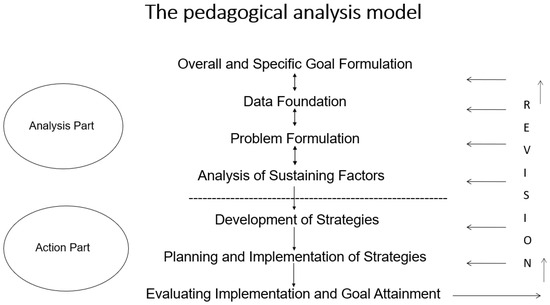

We used the PA model (Gustavsen & Nordahl, 2024; Nordahl, 2016) for data use by teachers and students, in collaboration with and guided by their school leaders. We used this in combination with the Shier (2019) model. The PA model involves a systematic and critical evaluation of teaching practices and learning environments (Gustavsen & Nordahl, 2024; Nordahl, 2016). This approach aims to enhance teaching and learning by identifying and analyzing educational challenges and proposing solutions based on data. This model, similar to other data-use models (e.g., Marsh, 2012), has two primary components: an analytical part and an action-oriented part (see Figure 1). The analytical part entails establishing a purpose, data collection and quality assessment, problem articulation, specific goal formulation, and an analysis of factors contributing to the problem. The action-oriented part encompasses the development of strategies, planning, and implementation of these strategies and the evaluation of both implementation and goal attainment. A paramount consideration is to complete the analytical portion prior to initiating the planning of the action-oriented part.

Figure 1.

PA data-use model (Nordahl, 2016, p. 47).

The process of pedagogical analysis is a collaborative one, involving teachers, school leaders, and, in this project, students, who work together in a PLC. This collective effort allows for the identification of challenges and the exploration of potential solutions, with active involvement from students.

3.2. Participants

We used a convenience sample for this study. This study is part of a larger research and development project, “PULSE1”, intended to increase student participation in data-informed school improvement. This project was initiated by district leaders at the municipal level from two regions in Norway, in partnership with the university located in this region. All the principals in the regions were asked if they were interested in joining the PULSE project. Five schools from three municipalities in the regions wanted to participate. An overview of the participants per school can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of participants.

In this project, each teacher used the PA model with students (in a whole-classroom approach) with teams of 4–6 students and tried to involve students in identifying and solving challenges based on data. Each student team went through the whole PA model as a PLC.

Teachers participating in the intervention received a manual with a detailed description of all the steps in the model and suggestions for how to conduct these steps with students at Levels 4 and 5 of participation per Shier’s (2019) model (M. M. F. Jenssen et al., 2024). The model consists of the following steps:

- Overall goal: Each student PLC should start by establishing an overall goal that they want to work on, related to the themes of a survey that is used for data collection in this step. The survey covers the following aspects: well-being, motivation, bullying, student participation, classroom structures and rules, and so forth. The teacher collects the input from the students, and, then, either the teacher decides (Level 4) on the purpose based on the student input or the teachers and students collectively decide (Level 5) on the purpose (e.g., via a whole-classroom discussion, via voting). In this step, it is important that a shared purpose is developed within the entire classroom.

- Data foundation: This step of the PA model involves systematically gathering and organizing information that represents various aspects of the school. Both quantitative (e.g., surveys, assessment results) and qualitative (e.g., classroom observations, interviews) data can be collected. After the data are collected, the quality (i.e., reliability and validity) of the data need to be checked. It is not possible to draw correct conclusions from poor-quality data. In this step, the teacher (Level 4) or the student PLCs together with the teacher (Level 5) decide which data to collect given the goal from the previous step and how to verify the quality of the collected data.

- Problem formulation: In this step, a final problem is formulated, related to the overall purpose and based on the data collected. For example, each student PLC can individually formulate a problem, after which all the problems are collectively discussed in the classroom, and a final shared problem is formulated by the teacher (Level 4) or the teachers and students together (Level 5). Problem definitions are often phrased in the form of statements or why questions.

- Specific goal formulation: Specific goals are related to the overall goal and should be formulated in a way that clearly expresses what is intended to be achieved. These goals should encompass both short-term and long-term objectives and be formulated in a way that allows for the evaluation of goal attainment. Here, for example, each PLC in the class can formulate a realistic and feasible goal that they present to the class, after which the teacher facilitates a discussion between the PLCs. The teacher can take the input of this discussion into account to formulate the final goal (Level 4). Alternatively, teachers and students could together decide (Level 5) on the final problem, for example, by voting for the best problem formulation.

- Analysis of factors that contribute to the problem: These factors are key elements within the pedagogical context that likely contribute to the problem. The analysis aims to identify and examine these factors to gain a deeper understanding of their impact on students’ situations and the perpetuation of difficulties. Here, for example, each PLC in the class can suggest possible factors that contribute to the problem and the data needed to investigate this. Then, all the PLCs present this information to each other. After the presentations, the teacher can decide (Level 4) which PLC is going to be responsible for investigating which possible causes and which data to collect. Alternatively, teachers and students could decide together (Level 5) on which PLC will investigate which possible causes.

- Development of strategies: The development of strategies is based on the analysis of the contributing factors. It is important to address multiple contributing factors simultaneously and to work systematically on implementing the strategies over time. When choosing strategies, it is advisable to rely on research-based knowledge wherever possible. In this step, the student PLCs brainstorm about possible strategies based on the identified contributing factors (for example, in their PLC or with the whole classroom) or select from a top-three list of strategies suggested by teachers. Either the teacher ultimately decides which strategies are going to be implemented (Level 4) or this is decided jointly (Level 5).

- Planning and implementation of strategies: When planning the implementation of strategies, careful consideration should be given to how they will be executed, who will be responsible for their implementation, and when they will be carried out. The teacher can plan and implement these strategies together with the student PLCs. The teacher can ultimately decide this (Level 4), or the decision can be made with the students (Level 5).

- Evaluating implementation and goal attainment: Planning and conducting an evaluation of the work performed increases the likelihood of realizing new practices. The evaluation of implementation and goal attainment should take place regularly and continually. It is important to focus on progress, that is, the extent or degree of improvement. Regardless of whether the goals are achieved or not, it is important to evaluate the potential reasons for this. In this step, for example, each student PLC can develop an evaluation plan, and, then, the teacher decides who does what (Level 4), or the teacher and students can make this decision together (Level 5).

Besides the manual, schools can use a digital learning environment to guide them through the steps, and four workshops were organized with all the schools participating in the intervention. The first two workshops were organized to prepare the participating schools for the intervention. These workshops covered topics such as data use, data literacy, the PA model, how to involve students, and how to prepare schools for this type of work. The school leaders at the participating schools also attended all workshops. In the third workshop, the results of the survey, which was the basis for Step 1 of the PA model, were discussed with the schools, and all schools made a plan for how they would start working with the students with the PA model. At the time of the fourth workshop, the schools had been working with the intervention for 4 months. In this workshop, the schools presented their progress and what they had learned, and the focus was on how to make the work sustainable.

Finally, each school had a coach (one of whom is author of this paper). The coach visited each school between three and five times. The focus of these coaching sessions was primarily on ensuring that school leaders and teachers had a comprehensive understanding of pedagogical analysis. Therefore, the coaches conducted workshops at each school and additionally ensured that teachers became familiar with the digital learning environment tool. The teachers used the digital tool to structure student work continuously. Several schools also desired a more in-depth examination of student participation and the various steps in Shier’s (2019) ladder. The coaches also spent a substantial amount of time discussing with school leaders how this project would be carried out regarding time schedules, the use of time at each step of the PA model, and how to support the teachers. Additionally, the school leaders and the coaches collaboratively formulated detailed plans for data collection at each individual school.

4. Materials and Methods

We conducted a qualitative interview study to answer the research question; details are provided below. Note that the students also collected data in their PLCs, which could be described as a type of action research. Carr and Kemmis (1986) define action research as inquiry undertaken by participants (in our case, students and teachers) in social situations (in our study, classrooms and the school) in order to improve their own practices (in this study, the quality of education), their understandings of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out. Students conducted their research around a cycle of inquiry (Johnson, 2003), in our case, the PA data-use model, and they conducted this collaboratively in a PLC (Capobianco & Feldman, 2010) with their teachers. We studied how school leaders supported teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs conducting their action research projects.

4.1. Instruments and Data Collection

The six school leaders of all participating schools were interviewed during the autumn of 2024. For triangulation purposes, we also interviewed a total of nine teachers during spring of 2024 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of number of participants interviewed.

We used an interview schedule for all the interviews. The first (also project leader) and third author carried out all the interviews2. For the school leaders, interview questions were grounded in the core functions as described in our theoretical framework (i.e., organizing and (re)designing the organization; managing the teaching and learning plan; and understanding people and supporting their development). For teachers, we asked questions about the levels of student participation in all steps in the PA model, as well as how leadership supported teachers in enhancing student participation in the use of data. Teacher interviews took place within the school facilities, while those with school leaders were conducted either in person at the school or digitally on Teams. On average, these interviews lasted 45 min. The interviews (originally in Norwegian) were recorded and transcribed verbatim. They were analyzed by the first and third author.

4.2. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. Information explaining the purpose and procedure of this study was provided to all participants, who were also assured that participants would remain anonymous and that participation was voluntary.

4.3. Data Quality and Analysis

Levels of student involvement reached at each of the schools were determined in a previous study (M. Jenssen et al., 2025), based on observations and interviews with teachers and students. Our analysis technique for describing leadership support consisted of multiple steps, inspired by thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In the first step, which involves becoming familiar with the data, the interview transcripts were re-read, and relevant sections or excerpts of text were marked. Next, the sections or excerpts for each school were coded using the core leadership functions for data-use PLCS based on van den Boom-Muilenburg et al. (2022), which offered a comprehensive framework and direction in approaching our data. Codes and categories (core functions) were discussed among the researchers to agree on how they perceived the codes and categories and which aspects of the data each core function captured. Although we had a deductive approach in our analytic work, we were open to the emergence of new codes (Braun & Clarke, 2006), and two new codes arose from our data (in italics in Table 4). Our codebook can be found in Appendix A. Finally, we placed all the schools in a common table based on the core functions. This gave us an overview of leadership practices for student participation in data use in each of the schools, as well as across the five schools (see Table 4).

Table 4.

An overview of leadership practices organized by core functions per school and associated level of student participation.

For reliability purposes, we used a systematic approach to data collection, consistent with our research question. We audio-recorded the interviews, and the instruments were all based on our theoretical framework and existing models. Finally, the first and third author coded 100% of the interviews together, discussing any initial differences in interpretation and adjusting the codebook accordingly.

For validity purposes, we used a matrix display to organize our results, including quotes from respondents. Quotes were translated into English. Moreover, we described the congruence with our theoretical framework (Poortman & Schildkamp, 2012).

5. Results

5.1. Student Participation in the Use of Data

The goal of this project was increasing student participation in the use of data, preferably to Levels 4 and 5 of Shier’s (2001) model. The results showed that this was successful in all five schools to a certain extent, although, in School 1, Level 3 and 4 were mostly present. Teachers were able to create forms of student participation at Level 4, or Levels 4 and 5 at several steps in the PA model in most schools. For example, in School 5, the student PLCs worked on problem formulation based on the data collected. Each student-PLC member wrote suggestions for problem formulation on sticky notes. They then shared these notes in their PLCs and worked on joint problem formulation. Next, each student PLC shared their joint problem definition on the board in the front of the classroom and explained their problem definition. Then, the students voted on the different problem definitions, and the classroom continued working through the steps of the PA model with the problem definition that received the most votes. The teacher of these students explained that the students participated actively in this process, and they decided what to do: “…then it was entirely up to them to take hold of what they wanted to. We didn’t set any guidelines on that” [translated from Norwegian to English].

In School 4, for example, the teachers and students used data to find factors that contributed to the problem being studied. The teachers summarized the findings, and, then, the students wrote down suggestions for strategies on their own sticky notes, which they then presented in their student PLC. Each PLC agreed on which measures they wanted to propose to the entire classroom. The proposals from all the PLCs were presented. The teacher took all the possible strategies and structure and presented them in an organized way, after which the teacher and students decided collectively which ones to implement.

Teachers were able to involve students in the use of data according to the PA model. School leaders in these schools actively supported the teachers in relation to student participation in data-use PLCs. As stated by one school leader (SL5), “I do not believe that we would have come this far in this work if we, the school leaders, had not been so close to” the teachers. Below, we describe how school leaders supported the teachers.

5.2. Organizing and (Re-)Designing the Organization

We found various strategies across the five schools regarding organizing and (re)designing, referring to a vision and priority for data use and student participation, and creating coherence with the school organization. First, the school leaders all developed and communicated a vision and goals for the PULSE project. However, the degree and method of communicating this vision, the goals, and expectations showed substantial variation among the schools. For example, School 1’s school leader had an expectation that this project would contribute to a more shared understanding of the concept of student participation. However, this was not explicitly communicated to the teachers. The school leader and teachers together developed goals for the work with student participation in data-use PLCs. A similar pattern was identified at School 3, where the leadership team and teachers collaboratively developed the goals, with an effort to highlight the coherence between previous school improvement focus areas and the PULSE-project: “So, it was essentially about making the connection between what we have been working on for a couple of years already, with student participation and this project, visible” (School Leader-SL3). On the other hand, at School 4, the school leader did not place much emphasis on the explicit communication of goals. The approach that was adopted could be characterized as a search for meaning and direction throughout the implementation process: “In a way, the road was made as we made the steps forward” (SL4).

At School 2, the school leaders did not place much emphasis on the communication of this project’s goals and expectations. This may be because the school leader herself chose to carry out the intervention with a group of students from 5th to 7th grade: “The school leader carried out the intervention herself. It was she who did the pedagogical analysis with the group of students” (Teacher-T4).

In School 5, both school leaders placed strong emphasis on the communication of goals and expectations: “It is stated in our school development plan that one of our focus areas is student participation in data-use PLCs” (SL5). During the initiation phase, time was spent on developing goals, both in the school’s development team and among the entire staff. There were expectations that all teachers should focus on student participation in their lessons. In addition, clearer goals and expectations were communicated to the teachers of the 5th and 6th grades, who were selected to carry out the intervention. Vision, goals, and expectations were also communicated by the school leader in the classrooms of the participating teachers, demonstrating the importance of the work to both teachers and students. As one of the teachers (T5) stated, “It was great that the PULSE project started with someone from the school’s leadership initiating a “kick-off” for the project for the students. This can be somewhat symbolic for the students that this work is important”.

5.3. Managing the Teaching and Learning Programme

The second core function of managing the teaching and learning plan refers to planning, monitoring, and evaluating student participation in data use. In School 1, regular meetings were scheduled for the entire staff and for participating teachers: “We have indeed allocated time for this project in the school’s overarching plans: the use of lessons for different classes and distribution of tasks and responsibilities” (SL1).

At School 2, where the school leader herself carried out the intervention with a group of students, regular meetings were held with one teacher from each of the three grades that were involved. The reason for involving the teachers in the planning was that, according to the school leader, the teachers should carry out observations during the various phases of the work and obtain knowledge and experience so that they could later carry out the intervention in their own classes. In the interview, the teachers said that it was fine with them that the school leader took responsibility for the first implementation and that they themselves were included in the planning, to observe and learn. These results pointed to a new code ‘School leader first to implement and experiment”, which was not included in our theoretical framework. It did contribute to one of the other core functions, being a role model. If school leaders implement an innovation themselves first, they can also be better role models for teachers.

At School 3, regular meetings were conducted with all teachers, with extra time allocated specifically for those involved in this project. The school leader at School 3 went beyond mere logistical arrangements and placed great emphasis on enhancing teachers’ knowledge and skills related to student participation and data use. The school leader provided time for the teachers to read Shier’s (2001) article on student participation. Together, the teachers and the school leader discussed different levels of student participation, the levels they were currently at in their own practice, and how they could achieve a higher level on the ladder. Before implementing any new strategies with students, the leader insisted on thorough preparation of the teachers. The leader stated, “So it was our knowledge base that had to be in place… Yes, that was very important, and we indeed dedicated a significant amount of time to this”.

The school leaders at Schools 4 and 5 also scheduled consistent meetings involving the entire staff, grade-level teams, and extra meetings for participating teachers: “The school leader has led the project, held onto it, and made plans and structures so the intervention could be carried out regularly” (T4). At School 5, an additional meeting schedule was set specifically for the two teachers participating in this project, which also included meetings with the school leadership.

Four network meetings were arranged for the participating schools by the coaches. Emphasizing and facilitating teachers’ participation in this network seemed important for the school leaders in Schools 1 and 4. They both highlighted the value of learning from colleagues in other schools.

School leaders from Schools 1, 3, 4, and 5 underscored the crucial role of school leaders as gatekeepers (another new code that arose from our data). Gatekeeping involves the careful selection and limitation of projects and initiatives that deserve time and attention (Forfang & Paulsen, 2019). As articulated by one school leader (SL3), “I am very focused on being the gatekeeper, so that we don’t have too many focus areas. We have committed our school to this project and that is what we are going to prioritize”. One school leader (SL4) also described how they protected the teachers involved in this project. If there was a need for substitutes elsewhere in the school, they did not reassign the teachers involved in this project.

5.4. Understanding People and Supporting Their Development

The third core function about understanding people and supporting their development, refers to providing support, being available and accessible, and being able to support connections and building trust.

School leaders at Schools 1, 3, and 4 demonstrated how they integrated observation and guidance as essential components of the learning process. After each classroom observation, they engaged in immediate discussions with the teachers, capitalizing on the freshness of the experience. This approach provided teachers with an opportunity for self-reflection on their practice and facilitated sharing of their perceptions of the intervention session’s progress. These discussions served as a platform for examining potential improvements and exploring alternative approaches, thus making them an invaluable tool for continuous professional development.

Two of the school leaders described how they supported teachers in their work by modelling desired practices. They achieved this by personally conducting sessions with the students, allowing teachers to observe firsthand. As one school leader (SL2) expressed, “So I see my role as essentially providing reassurance and showing”.

Providing individualized support is another leadership strategy that was found. For example, in School 1, school leaders adeptly addressed the individual needs of teachers by providing tailored support as and when it was required. The support could be small informal conversations aimed at ensuring a teacher’s confidence in the various phases of the PA model. In School 2, the school leader was notably active in the implementation process, not only demonstrating the practices that they desired to promote but also providing essential support. The school leaders acknowledged the significant roles of teachers and their need for guidance. In School 4, school leaders provided support in various formal and informal contexts and often through daily interactions with the teachers. In School 5, the leaders also provided support, including individual support, as and when required. As one of the school leaders expressed, “Because it’s also about being interested, right? That you are there and see what they are doing. But one of us was always there, so someone from the leadership team was always involved” (SL5).

The school leader at School 3 described how the leaders supported the teachers by taking part in the practical work: “It’s our culture that we try to do a lot of things together. Together as a leadership team and together with the teachers to the extent possible”. A member of the leadership team always participated in the teachers’ collaboration meetings, wondered along with them, and encouraged them both beforehand and along the way to try out what they had planned: “It was more about being the cheerleading squad, we try! Yes, this can go wrong, but how wrong can it go? And what is the worst that can happen?”

The teachers said that the school leaders had supported their development. The teachers at School 4 stated that the school leaders had been strongly involved. Furthermore, one of them pointed out the following:

If we had any questions, we could just ask the school leaders. We have asked for support and help throughout the whole implementation process, including when a school leader has been doing observations in the classroom. We did receive support and help when we needed it.

At School 3, the teachers emphasized that the principal and assistant principal had been present at almost all lessons related to the data use intervention with students. Furthermore, they pointed out that perhaps the school leaders could have asked even more about how things were going, but, at the same time, “One also feels that they have given us teachers trust and a responsibility for the project”. At School 5, the two teachers highlighted that the school leaders carried out the initial phases of the data-use intervention in the participating classes. Furthermore, they emphasized that the school leaders had supported the development of research-based strategies and actions. The teachers said that “The school leaders have really been great supporters and collaborators in this project” (T5).

6. Conclusions and Discussion

In summary, the results showed varying strategies across the schools regarding organizing and (re-) designing the organization. Communicating a clear vision, goals, and expectations regarding student participation in the use of data seemed to be important. However, the degree and method of communication differed per school. Communicating the vision and goals to students as well, to show the importance of student participation, was only explicitly mentioned for one school (School 5) but appeared to be of added value here.

Concerning the core function of managing the teaching and learning programme, all school leaders facilitated regular meetings and teachers’ participation in network meetings across schools, stressing the importance of participating in these networks. At one of the schools, the results also pointed to a possible new core function “School leader first to implement and experiment”, not included in our theoretical framework. At this school, the school leader piloted the intervention herself first. Her rationale was to try this out first on a small scale with a few students, while teachers followed the process. After this, the teachers were expected to implement this way of working in their own classroom. For this school, this supported the teachers in their work, and they could model their work after that of the school leader. However, as this is a small scale pilot, larger follow-up studies are needed to confirm if this really is a new core function that needs to be added to the theoretical framework.

Furthermore, providing the time that teachers needed was also found to be crucial, as already often mentioned in other studies with regard to teacher professional development, in general, and for working in PLCs specifically (Poortman et al., 2022; Vangrieken et al., 2017). In relation to this, the school leaders stressed the importance of “gatekeeping” (another new core component that arose from our data), selecting a limited number of projects and initiatives that deserve time and prioritizing the current project (Forfang & Paulsen, 2019). This could help create sufficient time and shows how their vision was made concrete in practice.

Finally, regarding understanding people and supporting their development, school leaders demonstrated crucial leadership behaviours such as providing individualized support, modelling desired practices, and being available and accessible. Observation and feedback mechanisms were also found to be important here. For example, school leaders observed the lessons of the participating teachers and provided them with feedback and/or modelled sessions with students while they were being observed by participating teachers. One school (School 3) leader, for example, specifically gave teachers time to read Shier’s (2001) article on student participation. Providing intensive support and being part of the intervention (V. Robinson et al., 2008) showed both teachers and students the importance of student participation and how to realize this in practice.

6.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

Given the promise of student participation in data use for student well-being, engagement, and performance (e.g., Jimerson et al., 2016; Jones & Hall, 2022; Yonezawa & Jones, 2007), schools need support in increasing student participation in practice. Moreover, this is important given that, although the selection of students happens in schools regularly, for example, via student councils, schools are looking for ways to involve all students and consult students on areas beyond practical or organizational matters. The PULSE approach shows how all students in a class can be involved in data use for educational improvement. This study confirms previous research findings in terms of the importance of school leadership confirming again the importance of the core functions as described above (e.g., Leithwood et al., 2008, 2020; V. Robinson et al., 2008) but also how, specifically, school leaders play a role in supporting student participation for data use in schools. Creating sufficient time and specifically gatekeeping, participating intensively, or first modelling the approach is especially important in such an approach, apart from providing support. In these cases, the results show what concrete school leader activities can support teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs.

This also has implications for practice and policy. In countries around the world, both data use and student participation are emphasized more and more. For example, student participation and data use are important topics at the national policy level in Norway. However, having national policies around student participation and data use is not enough. This also requires policy guidelines, procedures, and commitment (from school leaders) at the school level (Shier, 2001). The results of this study, in which we combined three well-known effective ingredients for school improvement, (1) student participation (e.g., Mager & Nowak, 2012), (2) data use (e.g., Grabarek & Kallemeyn, 2020), and (3) working in PLCs (Vangrieken et al., 2017), could be used as input for these much needed policy guidelines and procedures at the school level.

6.2. Limitations and Implications for Further Research

This is a small-scale exploratory study into how school leaders from a convenience sample supported student participation in data-use PLCs in their schools. School leaders volunteered to participate in this study, were already using the PA data-use model, and were enthusiastic about this project regarding how to increase student participation in the use of data. Therefore, this study does not allow for generalization (Yin, 2003), nor was this the purpose of our study. However, by providing qualitative descriptions based on interviews with both teachers and school leaders, we aimed to provide an in-depth description of how student participation was supported by school leaders in these schools, therefore supporting analytical generalization (Roald et al., 2021). Further research could include a larger sample of schools, teachers, and school leaders. This could also provide more insight into school leaders’ role, the leadership role of the teachers involved (i.e., distributed leadership; Leithwood et al., 2020), and the level of student participation achieved, as well as effects at the level of student performance over the long term.

Apart from describing how school leaders can support teachers in connection with student participation in data-use PLCs, this study indicates how distributed leadership can be expanded to include students also in what Holquist et al. (2023) defined as “student-led decision-making” (with adult support) (M. Jenssen et al., 2025). This is about teachers and school leaders giving students the power to make decisions and implement change: “Students can play vital parts in developing, implementing, and evaluating an agenda for change” (Holquist et al., 2023, p. 733). With scholarship on leadership traditionally focusing on leadership as an adult-only space (Holquist et al., 2023), further research could focus more on how student participation as distributed leadership affects school improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F., C.L.P., M.M.J., and K.S.; methodology, H.F., C.L.P., M.M.J., and K.S.; writing—original draft, H.F., C.L.P., M.M.J., and K.S.; writing—review and editing, H.F., C.L.P., M.M.J., and K.S.; project administration, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 400865, 18 June 2024). Information explaining the purpose and procedure of this study was provided to all participants, who were also assured that participants would remain anonymous and that participation was voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study can be made available upon request to the corresponding author and in accordance with ethical considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Code Book

Leadership

- Organizing and (re)designing the organization: Clear vision for student participation in data use (why is the school working with…)

- ○

- Making this a priority (facilitation, resources, scheduling).

- ○

- Coherence between student participation in data use and the school organization (connecting, e.g., taking into account at different levels coordination within the school so it can be organized and carried out; connection of school’s goals and intervention goals).

- Managing the teaching and learning plan: Planning

- ○

- Monitoring (e.g., observations by school leaders).

- ○

- Evaluation (e.g., by asking the students systematically what their experiences were).

- Understanding people and supporting their development: Providing support

- ○

- Being available and accessible (e.g., listening to teachers, being available for meetings/questions with teachers or students about the intervention).

- ○

- Being able to support connections and building trust (e.g., connections with the university coaches; building trust among teachers and students to work with the intervention).

- ○

- Being a role model (for student participation in data use, being actively engaged/participating).

- ○

- Being knowledgeable about this, as well as sharing knowledge (being able to answer questions about the intervention, communicating findings, and insights to others).

- New code(s) emerging from the data about leadership supporting student participation in data use not captured in the codes: gatekeeping, school leader first to implement and experiment (see Table 4, italics).

Codebook for interviews with school leaders and teachers

| Leadership Practices | Code Definition | Example Quote |

| Organizing and (re-) designing the organization | ||

| Vision and goals | Development of and communication of vision and goals | “The path was, in a way, created as we walked.” (SL1) |

| Managing the teaching and learning plan | ||

| Facilitating | Human resource management, use of time, Time for collaboration among staff | “We have indeed allocated time for it in the school’s overarching plans: which sessions in the different classes should be used for what, who should do what, what roles the various individuals should have, and what teachers need from the school’s leadership, and vice versa.” (SL1) |

| Planning | Staffing of teaching, monitoring student progress in learning, facilitating/shielding the employees | “The school leader has led the project, held onto it, and made plans and structures so the intervention could be carried out regularly” (SL4) |

| Understanding people and supporting their development | ||

| Actively involved | Actively involved in the pilot | “Because it’s also about being interested, right? That you are actually there and see what they are doing. But one of us was always there, so someone from the leadership team was always involved.” (SL5) |

| Supporting and motivating | Providing support | “After each round of observation, we always discussed it immediately on the same day. While the session was still fresh, we let the teachers reflect on how they thought it went. Yes, then we talk about it, right? About any possible tips, right? What could have been done differently there.” (SL5) |

| Modelling | Being a role model for student participation in data use | “And then it was us who started, it was me and the principal who sort of started inside (in the classes) with students, the first time.” (SL5) |

Notes

| 1 | Professional Learning Networks using data for learning and student engagement. |

| 2 | The second and fourth author were involved in designing this study and in writing this paper. They were not involved in coaching any participants, nor were they involved in data collection. |

| 3 | Italics mean new codes. |

References

- Anderson, S., Leithwood, K., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading data use in schools: Organizational conditions and practices at the school and district levels. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(3), 292–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansyari, M. F., Groot, W., & De Witte, K. (2020). Tracking the process of data use professional development interventions for instructional improvement: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 31, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Flood, J. (2020). The three roles of school leaders in maximizing the impact of Professional Learning Networks: A case study from England. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capobianco, B. M., & Feldman, A. (2010). Repositioning teacher action research in science teacher education. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 21, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Deakin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Datnow, A., & Hubbard, L. (2016). Teacher capacity for and beliefs about data-driven decision making: A literature review of international research. Journal of Educational Change, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutch Secondary Education Council. (2021). Convenant versterking samenspraak leerlingen [Agreement on increasing student participation]. Agreement by the Dutch Secondary Education Council and the Dutch National Student Interest Group. Available online: https://www.vo-raad.nl/nieuws/laks-en-vo-raad-tekenen-convenant-voor-versterking-inspraak-leerlingen (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Fielding, M. (2001). Beyond the rhetoric of student voice: New departures or new constraints in the transformation of 21st century schooling? In Forum for promoting 3–19 comprehensive education (Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 100–109). FORUM. [Google Scholar]

- Forfang, H., & Paulsen, J. M. (2019). Under what conditions do rural schools learn from their partners? Exploring the dynamics of educational infrastructure and absorptive capacity in inter-organisationallearning leadership. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 3(4), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forfang, H., & Paulsen, J. M. (2021). Linking school leaders’ core practices to organizational school climate and student achievements in Norwegian high-performing and low-performing rural schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(1), 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gebre, E. H. (2018). Young adults’ understanding and use of data: Insights for fostering secondary school students’ data literacy. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 18(4), 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabarek, J., & Kallemeyn, L. M. (2020). Does teacher data use lead to improved student achievement? A review of the empirical evidence. Teachers College Record, 122(12), 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, A. M., & Nordahl, T. (2024). Pedagogisk analyse: En modell for kvalitetsvurdering og kvalitetsutvikling i skolen [Pedagogical analysis: A model for quality assessment and quality development in schools]. In H. Forfang, & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Ledelse av kvalitetsarbeid i skolen (pp. 111–136). Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. UNICEF International Child Development Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, M. A., & Scheerens, J. (2013). School leadership effects revisited: A review of empirical studies guided by indirect-effect models. School Leadership & Management, 33(4), 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Holquist, S. E., Mitra, D. L., Conner, J., & Wright, N. L. (2023). What is student voice anyway? The intersection of student voice practices and shared leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(4), 703–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, M., Poortman, C. L., Schildkamp, K., & Forfang, H. (2025, February 10–14). Student involvement in the use of data in professional learning communities: Level of involvement and effects. ICSEI Congress [Paper presentation], Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen, M. M. F., Myhr, L. A., & Nordahl, T. (2024). Elevenes medvirkning i kvalitetsarbeidet [Student participation in quality work]. In M. Paulsen Jan, & H. Forfang (Eds.), Ledelse av kvalitetsarbeid i skolen (pp. 136–160). Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson, J. B., Cho, V., & Wayman, J. C. (2016). Student-involved data use: Teacher practices and considerations for professional learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. P. (2003). What every teacher should know about action research (3rd ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. A., & Hall, V. (2022). Redefining student voice: Applying the lens of critical pragmatism. Oxford Review of Education, 48(5), 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. K., & McNaughton, S. (2016). The impact of data use professional development on student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2021). A review of evidence about equitable school leadership. Education Sciences, 11(8), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Strauss, T. (2010). Leading school turnaround: How successful leaders transform low-performing schools (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, U., & Nowak, P. (2012). Effects of student participation in decision making at school. A systematic review and synthesis of empirical research. Educational Research Review, 7(1), 38–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandinach, E. B., & Jimerson, J. B. (2016). Teachers learning how to use data: A synthesis of the issues and what is known. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A. (2012). Interventions promoting educators’ use of data: Research insights and gaps. Teachers College Record, 114(11), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A., & Farrell, C. C. (2015). How leaders can support teachers with data-driven decision making: A framework for understanding capacity building. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(2), 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Meelissen, M., Maassen, N., Gubbels, J., van Langen, A., Valk, J., Dood, C., Derks, I., ’t Zandt, M. I., & Wolbers, M. (2023). Resultaten PISA-2022 in vogelvlucht [PISA results at a glance]. University of Twente. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D. L. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106(4), 651–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, T. (2016). Bruk av kartleggingsresultater i skolen: Fra data om skolen til pedagogisk praksis [Using survey results in schools: From school data to pedagogical practice]. Gyldendal akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2017). Overordnet del—Verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen [Core curriculum—Values and principles for primary and secondary education]. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- OECD. (2019). An OECD learning framework 2030. In The future of education and labor (pp. 23–35). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman, C. L., Brown, C., & Schildkamp, K. (2022). Professional learning networks: A conceptual model and research opportunities. Educational Research, 64(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortman, C. L., & Schildkamp, K. (2012). Alternative quality standards in qualitative research? Quality & Quantity, 46, 1727–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Rinnooy Kan, W. F., Munniksma, A., Volman, M., & Dijkstra, A. B. (2023). Practicing voice: Student voice experiences, democratic school culture and students’ attitudes towards voice. Research Papers in Education, 39(4), 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roald, T., Køppe, S., Bechmann Jensen, T., Moeskjær Hansen, J., & Levin, K. (2021). Why do we always generalize in qualitative research? Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V., & Gray, E. (2019). What difference does school leadership make to student outcomes? Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(2), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. M. (2010). From instructional leadership to leadership capabilities: Empirical findings and methodological challenges. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkamp, K., Poortman, C. L., Ebbeler, J., & Pieters, J. M. (2019). How school leaders can build effective data teams: Five building blocks for a new wave of data-informed decision making. Journal of Educational Change, 20(3), 283–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children & Society, 15(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. (2019). Student voice and children’s rights: Power, empowerment, and “protagonismo”. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of teacher education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijbos, J., & Engels, N. (2023). Micropolitical strategies in student-teacher partnerships: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives on student voice experiences. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Przybylski, R., & Johnson, B. J. (2016). A review of research on teachers’ use of student data: From the perspective of school leadership. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 28, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boom-Muilenburg, S. N., de Vries, S., van Veen, K., Poortman, C., & Schildkamp, K. (2022). Leadership practices and sustained lesson study. Educational Research, 64(3), 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Scheer, E. A., & Visscher, A. J. (2018). Effects of a data-based decision-making intervention for teachers on students’ mathematical achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(3), 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Visscher, A. J., & Fox, J. P. (2016). Assessing the effects of a school-wide data-based decision-making intervention on student achievement growth in primary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 53(2), 360–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennergren, A. C., & Blossing, U. (2017). Teachers and students together in a professional learning community. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(1), 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yonezawa, S., & Jones, M. (2007). Using students’ voices to inform and evaluate secondary school reform. In International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school. Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).