Abstract

This study explores the effectiveness of Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (TAVL) using student-created video learning materials within a tertiary-level English as a Foreign Language (EFL) flipped classroom. By leveraging the flipped classroom model, which allocates classroom time for interactive activities and shifts instructional content delivery outside of class, the research investigates how student-produced videos can enhance vocabulary acquisition and retention. Conducted with 47 university students from a Translation and Translation Studies course, the study aims to fill a gap in empirical evidence regarding this innovative approach. Quantitative analysis revealed that students who created and utilized videos (Group 1) showed the highest improvement in vocabulary scores, followed by those who only used the videos (Group 2), with the control group relying on traditional teacher-led methods showing the least improvement. Qualitative feedback highlighted that video creators experienced deeper engagement and better vocabulary retention, while users appreciated the videos’ visual and auditory elements but faced challenges with vocabulary overload. The findings suggest that incorporating student-created videos into the curriculum fosters a dynamic and collaborative learning environment, offering practical implications for enhancing vocabulary instruction through technology-enhanced pedagogical practices. Future research should focus on optimizing video production processes and integrating these methods with traditional teaching for comprehensive vocabulary learning.

1. Introduction

Many undergraduate students face significant challenges in mastering foreign language vocabulary and developing a lexicon of both general and technical terminologies in their EFL language courses. A typical EFL course often includes short reading passages, vocabulary memorization, and grammar exercises, with vocabulary acquisition built on direct teaching instruction, such as completing vocabulary tasks and activities either in the classroom or at home (Sinyashina, 2020; Nami & Asadnia, 2024). These courses aim to build a solid foundation in English, but students frequently struggle with the volume of new vocabulary and the need to retain and apply these words effectively in various contexts (Miroshnychenko, 2024; Afzal, 2019). Unfortunately, this approach often leads to poor outcomes, as students quickly forget the words and fail to perform well on tests. Research highlights these challenges. For instance, Abramova et al. (2013) discuss the difficulties faced by university students in acquiring English vocabulary, emphasizing the need for more interactive and student-centered teaching methods. Similarly, Kovsh (2020) points out the importance of integrating multimedia resources and technology to enhance vocabulary learning and retention.

Recognizing these persistent challenges, the integration of technology into language education has emerged as a promising solution to address vocabulary learning difficulties, particularly in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instruction at the tertiary level. Among the innovative approaches gaining prominence is the flipped classroom model, which inverts conventional teaching methods by delivering instructional content outside of class and reserving classroom time for interactive activities. This strategy has been shown to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes (Bergmann & Sams, 2012). Within this flipped classroom framework, Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (TAVL) plays a crucial role by leveraging digital tools to facilitate vocabulary acquisition and retention (Pratiwi et al., 2024).

Vocabulary is widely recognized as a crucial component in language learning and communication, serving as the foundation for understanding and conveying meaning (Barani & Seyyedrezaie, 2013; Folse, 2004). Research indicates that vocabulary knowledge often surpasses grammar in importance for effective communication, and neglecting it in language courses can significantly hinder learners’ progress (Barani & Seyyedrezaie, 2013). The rapid advancement of new technologies has provided learners with unprecedented opportunities to address the challenge of acquiring L2 vocabulary. Modern tools, such as language learning apps, online communication platforms, digital glosses, and educational games on computers and mobile devices, offer diverse methods for vocabulary development. Recent research highlights the effectiveness of Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning in EFL contexts, showing that these methods outperform traditional instruction with moderate to large effect sizes (Hao et al., 2021; Yu & Trainin, 2021).

In a recent meta-analysis, Webb et al. (2023) asserted that both incidental and intentional learning activities have significantly positive effects on vocabulary learning. Sinyashina (2020) compared “incidental + intentional” and “intentional + incidental” learning methods, finding the former to be potentially more effective. Reynolds et al. (2022) conducted a meta-analysis revealing that captioned and subtitled videos positively impact vocabulary learning, with intralingual captions showing the largest effect. Teng (2022) demonstrated that viewing captioned videos led to the most pronounced incidental vocabulary learning outcomes compared to reading and listening, with prior vocabulary knowledge being more important than frequency. Lu (2022) reviewed both incidental and intentional learning strategies, highlighting the potential of video games, background music, and cartoons for incidental learning, while also discussing conventional intentional methods like word-lists and flashcards. The study also introduced Data-Driven Learning as a new approach combining both methods, emphasizing the importance of learners’ thinking and recognition skills.

A promising development within TAVL is the use of self-created video and digital storytelling (Yu & Trainin, 2021; Nami & Asadnia, 2024). This approach has gained significant prominence due to the increasing popularity of platforms such as TikTok and other similar video-based mobile applications, as well as the influence of YouTubers and social media influencers. It encourages students to create their own video content to illustrate and contextualize new vocabulary, transforming passive learning into an active, student-centered process (Hafner & Miller, 2011). By producing educational videos, students not only encounter new lexical items but also apply them in meaningful contexts, enhancing their understanding and retention (Swain et al., 2015). Self-made digital stories have been found to improve vocabulary acquisition by contextualizing words in multimodal narratives and enhancing cognitive–affective engagement (Nami & Asadnia, 2024). Additionally, audio–visual materials, especially videos, have demonstrated positive effects on incidental vocabulary learning by providing meaningful contexts (Karami, 2019). This method allows students to use vocabulary in authentic settings, deepening their grasp of practical applications and improving their ability to recall and use vocabulary effectively.

While the use of video-based materials for vocabulary learning has been extensively studied, there remains a significant gap in research specifically addressing the impact of self-created videos. Current literature predominantly explores the benefits of consuming pre-made video content, with limited attention given to the potential advantages of students creating their own videos (Yawiloeng, 2020). This gap is particularly evident in the context of higher education EFL settings, where empirical evidence on the effectiveness of self-produced videos in enhancing vocabulary acquisition is scarce (Hafner & Miller, 2011; Hung, 2015). Additionally, there is a lack of research comparing the vocabulary learning outcomes between students who produce videos and those who consume them within a flipped classroom model. Understanding whether the act of creating video content leads to deeper engagement and better retention of vocabulary compared to merely watching videos is crucial for optimizing instructional strategies. Addressing these gaps could provide valuable insights into the pedagogical benefits of integrating self-produced videos into language learning curricula.

To address this gap, the present study aims to investigate EFL students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of student-created video learning materials in a tertiary-level EFL flipped classroom. This study, conducted with 47 EFL university students of Translation and Translation Studies, explores the following research questions:

- RQ1. How does the use of student-created videos (SCVs) in a flipped classroom setting impact vocabulary acquisition compared to vocabulary teaching based on traditional teacher-led methods?

- RQ2. What are students’ perceptions of producing self-created videos as a learning tool within the EFL flipped classroom?

- RQ3. What are students’ perceptions of using self-created videos as a learning tool within the EFL flipped classroom?

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: The paper opens with an in-depth exploration of the theoretical foundations and a thorough review of relevant research in the field. This is followed by a detailed account of the study’s methodology and key findings. The final section examines the pedagogical implications of the study within the EFL context, providing a critical analysis and offering actionable insights for practice.

2. Theoretical Background

Self-created videos, including educational videos, digital stories, and other multimedia projects, have emerged as an innovative, technology-driven pedagogical approach that significantly enhances language learning and motivation. These videos are particularly effective for vocabulary acquisition, as they engage students in multimodal processing, promoting active learning and vocabulary building (Anas, 2019). Recent studies have shown that short videos can enhance vocabulary acquisition through interactive and engaging content (Chen, 2023). The process of creating videos requires students to actively engage with the material, think critically about presentation, and use language creatively, which reinforces vocabulary and concepts, making them more memorable. Additionally, by creating videos, students develop agency in their learning, improve language skills, and enhance intercultural communication competence (Guenier, 2023). Collaborative video projects further foster student motivation, participation, and vocabulary enrichment in EFL contexts (Abdulrahman & Basalama, 2019).

Supporting this approach, Dale’s (1969) cone of learning model suggests that students retain information differently based on the method of learning, such as reading, listening, viewing images, watching videos, or participating in hands-on activities. Bruner (1983) emphasizes that learning through linguistic symbols and experiential knowledge is more effective for cognitive development than merely reading and writing. In the context of learning English vocabulary, it is crucial for students to grasp the meanings of words through both iconic and symbolic representations. A widely accepted approach to teaching new vocabulary to L2 learners involves using visual aids that are linked to the target vocabulary (Gersten & Baker, 2000). Research in the L2 domain, particularly on multimedia glossing, has shown that visual supports, such as pictures, are effective for incidental vocabulary acquisition (e.g., Al-Seghayer, 2001; Kost et al., 1999; Yanguas, 2009). These findings highlight the pedagogical value of using visual aids, including videos, to enhance vocabulary learning.

The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) and the Dual Coding Theory further provide a robust foundation for using visual aids in L2 vocabulary acquisition. These theories suggest that learners process information through dual channels (verbal and visual) with limited capacity, requiring active processing for meaningful learning (Rudolph, 2017; Plass & Jones, 2005). Dual Coding Theory, proposed by Allan Paivio, posits that humans have two interconnected systems for processing information: verbal and visual. Cognition is enhanced when information is presented in both formats, facilitating better processing, storage, and retrieval. When learners encounter new vocabulary with relevant images, they create stronger mental associations, leading to improved recall and understanding (Paivio, 1986, 2010). Mayer’s CTML builds on Dual Coding Theory and emphasizes the importance of multimedia components in instructional materials. This theory is based on three assumptions: there are two separate channels (auditory and visual) for processing information, each channel has limited capacity, and learning is an active process of filtering, selecting, organizing, and integrating information. CTML suggests that people learn more effectively from words and pictures than from words alone because multimedia instruction engages multiple cognitive processes. Visual aids help reduce cognitive load and enhance comprehension (Mayer, 2021; Plass & Jones, 2005). Both theories underscore the importance of using visual aids in vocabulary instruction, providing a comprehensive foundation for the use of videos and other visual aids in enhancing L2 vocabulary acquisition.

Research on video-based materials highlights their potential for enhancing vocabulary knowledge (Reynolds et al., 2022; Karami, 2019). However, much of this research has primarily examined the advantages of using pre-produced video content. It is well established that input plays a major role in second language (L2) acquisition, with audio–visual input like TV and video being particularly rich sources. These materials expose learners to authentic language use (Lin, 2014) and combine imagery and audio to stimulate comprehension and vocabulary learning (Rodgers, 2018). Research shows that out-of-class exposure, such as watching TV and videos in a foreign language, is popular among learners and positively impacts listening, reading proficiency, and vocabulary knowledge (Kuppens, 2010; Lindgren & Muñoz, 2013; Peters, 2018; De Wilde et al., 2019). Research has also examined the effects of audio–visual input from various angles, including the vocabulary demands of TV programs (Webb & Rodgers, 2009; Rodgers & Webb, 2011) and the role of TV programs in incidental vocabulary learning (Peters & Webb, 2018; Rodgers & Webb, 2017). The benefits of on-screen text, such as subtitles and captions, have been widely studied, showing that captioned videos enhance comprehension and vocabulary learning (Montero Perez et al., 2013) and improve automatic word recognition (Mitterer & McQueen, 2009). Other research has compared the effects of L1 subtitles and captions (Peters et al., 2016) and investigated different types of captions, such as keyword captions.

The impact of self-produced video materials on vocabulary learning is relatively underexplored. While video-based approaches have the potential to help learners move beyond the rote memorization of vocabulary—a common challenge in higher education—little research so far has been performed to investigate the effectiveness of learners creating their own video content, especially in flipped classroom contexts. It is worth noting, however, that several studies suggest that greater involvement in video creation, annotation, or dubbing is often associated with improved vocabulary acquisition. For instance, Zhou and Wu (2024) conducted a study with 26 university undergraduates who watched video clips using two techniques for new words: generating their own contextual clues and using instructor-provided clues. The results showed that learners who generated their own contextual clues had superior vocabulary learning performance compared to those who used instructor-provided clues (Zhou & Wu, 2024). Similarly, Nami and Asadnia (2024) found that students who engaged in collaborative digital storytelling (DST) projects outperformed control groups on vocabulary tests. DST empowered students to integrate vocabulary learning into daily contexts, experience peer-promoted learning, contextualize vocabulary in multimodal stories, personalize the learning process, and enhance engagement. Additionally, research by Argudo-Serrano et al. (2024) supports the effectiveness of student-made videos in enhancing English proficiency. Their study compared the outcomes of student-made videos versus traditional teacher-led methods in EFL classes and found that student-made videos led to better learning outcomes.

Although studies on the use of self-produced videos in a flipped classroom context are scarce, most reflect the positive impact of flipped instruction on vocabulary learning. For instance, Ebadi et al. (2022) found significant improvements in vocabulary acquisition for students experiencing flipped learning, especially in form and meaning, with students appreciating the online materials and collaborative activities. Similarly, Al Qasmi et al. (2022) showed that Omani students in flipped classrooms outperformed those in conventional settings and had higher motivation. However, some other studies, such as Engin (2014), suggest that while student-created videos can promote second language learning by encouraging research and explanation, students often prefer teacher-produced explanations and have concerns about the trustworthiness of peer-created tutorials. These findings indicate that while self-produced videos in flipped learning contexts can enhance vocabulary acquisition and engagement, challenges remain regarding student preferences and the perceived reliability of peer-generated content.

In almost all these studies, the positive impact of video-based materials on vocabulary learning is evident. However, the specific benefits of self-produced videos, particularly in flipped classroom contexts, remain underexplored. This study aims to address this gap by systematically investigating the effectiveness of self-developed videos for vocabulary learning in EFL university courses. By doing so, it seeks to provide insights into how self-produced videos can enhance vocabulary acquisition and create rewarding learning experiences for students. This research responds to the need for more effective and engaging learning strategies in higher education, offering potential solutions to the challenges of rote memorization and passive learning.

3. Method

This study employed a descriptive, exploratory, and experimental research design, conducted on a small scale and over a relatively short duration. The primary objective was to systematically collect and present data on the implementation of student-created video (SCV)-assisted vocabulary teaching and learning in a flipped English Language Teaching (ELT) classroom.

The research was divided into two stages. Stage 1 aimed to quantitatively analyze the effect of producing or using SCVs in a flipped classroom on vocabulary acquisition. This stage involved both a pre-test and a post-test designed to assess students’ vocabulary acquisition. The participants were divided into three groups: Group 1, where students created vocabulary learning videos weekly for 16 flipped thematic classes focused on vocabulary; Group 2, where students used the videos created by Group 1 for vocabulary acquisition in a flipped classroom setting; and Group 3, the control group, which received face-to-face instruction following a traditional teacher-led methodology grounded in direct instruction, repetition and practice. In this instruction, no video materials were utilized. The focus remained on traditional teaching aids such as textbooks, worksheets, and verbal explanations provided by the instructor. This method aimed to provide a baseline for comparison with the experimental groups using student-created video-based learning.

Stage 2 involved a qualitative exploratory case study to gather in-depth insights into students’ perspectives on SCV-assisted vocabulary learning. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with selected participants from Groups 1 and 2. The aim was to explore their experiences, attitudes, and perceptions regarding the SCV-based methodology.

3.1. Participants

The study involved 47 second-year university students (10 male, 37 female) enrolled in the Specialist Program “Translation and Translation Studies”. Participants, aged 20–21, were undertaking the “Active Vocabulary” module as part of their compulsory four-semester English language course. This course encompasses various components, including “Practice of Oral and Written Speech”, “Grammar”, “Phonetics”, and “Active Vocabulary” (offered in semesters 3 and 4). The primary aim of the course is to enhance students’ communicative competence at the B2+/C1 levels, with elements of C2 level, according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001), and to prepare them for professional communication in English. The demographic breakdown of participants included 43 Russian speakers, 3 Tajik speakers, and 1 Azerbaijani speaker.

The study involved students from three pre-existing groups, which remained unchanged throughout the research period. These groups were not specifically created for the purposes of this study but were established learning cohorts already following a standardized curriculum across all core subjects. Consequently, the group sizes varied: Condition 1 (n = 16), Condition 2 (n = 17), and Condition 3 (n = 14). To address the non-random assignment of participants, an initial diagnostic test, including a lexical component, was administered. This test aimed to ensure that the groups had comparable levels of language proficiency at the outset. While this approach does not entirely eliminate the possibility of pre-existing differences influencing the results, it significantly mitigates this potential limitation.

Fourteen students from the study expressed their desire to participate in the interview phase. Detailed demographic information for these interview participants is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic information.

3.2. Materials and Instruments

3.2.1. Student-Created Videos

The primary materials for this project were the student-created videos (SCVs), which played a crucial role in introducing and reinforcing new vocabulary. These videos were designed to be both engaging and educational, following a set of structured guidelines to maximize their effectiveness (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Guidelines for student-created videos.

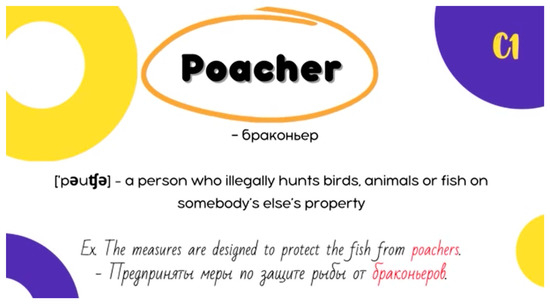

In addition to these steps, the videos incorporated excerpts from movies and documentaries where the target vocabulary was used in context, enhancing the learning experience (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of a student-created video illustrating a vocabulary word.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of a student-created video featuring a news excerpt.

3.2.2. Pre- and Post-Tests

To evaluate the effectiveness of vocabulary instruction in the Active Vocabulary class, pre-tests and post-tests were administered (See Appendix A). The pre-tests established a baseline measure of students’ pre-existing knowledge of the target vocabulary domain rather than testing knowledge of the specific words to be taught. Approximately 25% of the words intended for instruction were already known by the students, as indicated by the pre-test and were therefore excluded from the teaching phase. Instruction focused solely on new vocabulary. To measure actual learning, the post-tests assessed only the newly introduced vocabulary.

Thematically organized words were included in the Active Vocabulary course materials, which were developed by the Linguistics department. Vocabulary selection took into account the students’ English proficiency level, as determined through diagnostic testing. High-frequency words were selected based on the students’ age, interests, daily experiences, and prior knowledge of the subject matter, ensuring direct alignment with course objectives.

The assessment consisted of 200 items across themes such as Crime and Punishment, Money and Banking, Houses and Homes, Religion, Pastimes, and Travel, divided into four sections: Word Recognition (50 multiple-choice items), Meaning Recognition (50 multiple-choice items), Definition-Based Word Recall (50 items), and Translation-Based Word Recall (50 items). Each correct answer was worth one point, so the total score was 200.

The multiple-choice options were crafted using simpler language compared to the target vocabulary to ensure clarity. In the definition-based recall section, definitions were formulated using higher-frequency words wherever possible to facilitate comprehension. Bilingual test items were incorporated, with synonyms provided for translation to accommodate linguistic needs (see Appendix A). This structured approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the students’ vocabulary acquisition, ensuring that the assessment accurately reflected their learning outcomes.

3.2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

To gain qualitative insights into students’ perceptions and experiences, semi-structured interviews were conducted via the MS Teams platform (See Appendix B). This platform was selected as it serves as the university’s official online communication tool, guaranteeing full access for both students and faculty. The interviews aimed to explore students’ views on the use of student-created videos (SCVs) as a learning tool and their effectiveness within the flipped classroom. Each interview lasted approximately 10 min and was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Conducting the interviews in English, the interviewers ensured that students were informed that their recordings would be anonymized and used solely for research purposes. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, allowing the use and publication of the study results.

The interviews were structured around two main focus areas: the first group of questions aimed to understand students’ perceptions of producing SCVs, including the benefits and challenges associated with this method. The second group of questions focused on students’ views regarding SCV materials specifically developed for vocabulary learning, addressing both the benefits and challenges encountered in this approach. This comprehensive approach facilitated a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of SCVs in enhancing the flipped ELT classroom experience.

To design the interview questions for exploring students’ perspectives on the experimental vocabulary teaching approach, a combination of methods was employed. First, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to examine existing research on vocabulary acquisition and teaching methodologies. This review helped identify key themes and commonly investigated questions in similar studies. Based on these insights, clear, concise, and unambiguous questions were then developed, ensuring alignment with the study’s objectives. These questions were finally pilot-tested to confirm their relevance and suitability, particularly in the context of student-created videos (SCVs) and flipped classroom environments (see Appendix B).

3.3. Procedures

Stage 1: Experimental Teaching. The experimental teaching phase lasted for 18 weeks, from 11 February 2022 to 10 June 2022. The objective was to analyze the effects of SCV and compare the progress of the students in the three groups: the video creators, the video users, and those who followed a conventional methodology. One single instructor, who was also one of the researchers, presented the same vocabulary content to three groups. However, the instruction was delivered at different times, always using distinct teaching methods specifically tailored to each group. This design ensured consistency in the vocabulary content while facilitating a rigorous comparative analysis of the pedagogical approaches.

Group 1: The video creators produced weekly vocabulary learning videos for each of the 16 flipped thematic vocabulary classes (See Appendix C). Organized into four groups of four, they uploaded their videos to the MS Teams platform several days before each lesson. During class, these videos served as the foundation for various activities designed to practice and reinforce the newly introduced vocabulary. All materials were compiled into a dedicated e-booklet. Vocabulary acquisition was assessed at the end of each lesson.

Group 2: The video users did not produce any videos themselves but instead used those created by Group 1. Their homework consisted of watching these videos to independently learn new vocabulary, enabling more classroom time to be dedicated to in-depth exploration of the content. Vocabulary acquisition was evaluated at the end of each lesson.

Group 3: The control group followed a traditional teaching methodology. They participated in face-to-face instruction, engaged in vocabulary practice during class, and completed homework assignments. To reinforce retention and understanding, the teaching process included brief tests at the start of each lesson to assess their grasp of the vocabulary.

A summary of the activities and methodologies for each group is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Group 1, 2 and 3 activity schedule.

Out of the 18 lessons, two were allocated for organization and testing. The first lesson was dedicated to the pre-test, while the final lesson focused on the post-test. The remaining 16 lessons were thematically structured for vocabulary teaching and practice, as outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Thematic vocabulary lesson plan.

Stage 2: Interviews. Stage 2 consisted of semi-structured interviews with selected students from Group 1 (8 out of 16) and Group 2 (6 out of 17). The goal was to investigate their attitudes toward producing SCVs in a flipped classroom setting and their perceptions of the Active Vocabulary flipped classroom methodology using SCVs.

A mixed-methods approach was followed for data analysis, leveraging the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data from pre-tests and post-tests were analyzed using SPSS version 29.0 to evaluate vocabulary acquisition across the three groups. This analysis also facilitated a comparison of the impacts of producing and using SCVs versus the traditional teaching methods employed in the control group. For the qualitative part of the analysis, we conducted interviews with students, which were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis to gain deeper insights into their experiences and perceptions. To further explore students’ views on creating vocabulary learning videos and using SCV materials in the flipped English Language Teaching (ELT) classroom, we employed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). The process was systematic and rigorous. First, we immersed ourselves in the data by transcribing the interview recordings, carefully reading and rereading the transcripts, and making detailed initial notes. Next, we conducted inductive thematic coding to identify key themes aligned with the study’s objectives, ensuring a focus on students’ perspectives while minimizing biases from prior research (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Finally, we reviewed and refined the emerging themes to produce a comprehensive and coherent set of subthemes that accurately captured participants’ experiences and insights. The analysis was conducted manually to ensure close, systematic engagement with the data and to preserve the contextual depth of participants’ responses.

To ensure the robustness of the analysis, two independent researchers coded the transcriptions separately and then compared their results to enhance interrater reliability (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007). Interrater reliability was approximately 97%, indicating a high degree of consistency in coding between the researchers.

4. Analysis of Results

To address the first research question, a descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS (IBM Corp, 2022) to evaluate the impact of student-created videos (SCVs) on vocabulary acquisition. The analysis revealed notable differences in performance across the three groups.

The pre-test scores were relatively similar across all groups, indicating comparable initial vocabulary knowledge (see Table 5). Group 1 had an average pre-test score of 25.56, Group 2 scored 24.94, and Group 3 had a score of 25.50. These results suggest that the groups started with similar levels of vocabulary understanding. However, the post-test scores exhibited significant variations (Table 6). Group 1, which utilized SCVs in a flipped classroom setting, achieved the highest mean post-test score of 87.69, reflecting an improvement of 62.13 points from their pre-test score and indicating substantial gains in vocabulary acquisition. Group 2, which used the SCVs created by Group 1, had a mean post-test score of 83.12, showing an improvement of 58.18 points from their pre-test score. Although significant, their gains were slightly less than those of Group 1. Group 3, the control group, recorded the lowest mean post-test score of 79.64 and an improvement of 54.14 points from their pre-test score. This group also exhibited the highest variability in scores, which could suggest inconsistencies in the effectiveness of the traditional method, with varying levels of student engagement.

Table 5.

Average pre-test scores across the three groups.

Table 6.

Comparison of the post-test performance of the three groups.

To address the second research question concerning students’ perceptions of creating self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom, qualitative data from Group 1 were analyzed. The findings revealed a spectrum of both positive and negative perceptions regarding this approach. In relation to the positive perceptions of creating SCVs as a learning tool, several key themes emerged: vocabulary expansion, SCVs’ effectiveness as a teaching and learning tool, benefits for visual learners, increased engagement and enjoyment, the development of digital competencies, and complementary use alongside traditional instructional methods (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Students’ positive perceptions of creating self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom.

Conversely, the analysis also revealed several negative perceptions associated with the use of SCVs as a learning tool, underscoring specific challenges and concerns expressed by students. The predominant themes included the time-consuming nature of video production, difficulties in achieving high production quality, challenges related to group collaboration, excessive video length, and feelings of embarrassment during the recording process (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Students’ negative perceptions of creating self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom.

Overall, the analysis of Group 1’s perceptions highlighted both the strengths and challenges of creating self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom. On the positive side, students reported significant vocabulary enhancement, as the production process required extensive interaction with new vocabulary, repetition, and contextual learning. SCVs were also viewed as an effective teaching and learning tool, particularly for visual learners, who found the method helpful for retaining and using vocabulary in speech. Many students enjoyed the creative process, which motivated them and deepened their understanding of vocabulary. Additionally, the project fostered the development of digital skills, such as video editing, which students recognized as valuable for 21st-century learning. Some suggested combining SCVs with traditional methods to optimize learning outcomes. However, the method also faced criticism. Students found the process time-consuming, with difficulties balancing video production with other academic commitments. Technical challenges, such as maintaining high production quality, and teamwork issues, including delays caused by reliance on peers, were notable drawbacks. Other concerns included the length of videos, which some students felt should be shorter to accommodate today’s attention spans and feelings of embarrassment about appearing in videos.

To address the third research question regarding students’ perceptions of using self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom, qualitative data from Group 1 were analyzed. The findings reveal a range of both positive and negative perceptions about this approach. Positive perceptions of using SCVs as a learning tool included themes such as their effectiveness in teaching and learning, vocabulary expansion, increased motivation, innovative use of technology, and integration with traditional methods. Conversely, negative perceptions highlighted issues such as the overwhelming vocabulary load, deadline issues affecting preparation time, and retention challenges with new vocabulary. Table 9 provides a more detailed description of each of these themes, including students’ comments.

Table 9.

Students’ perceptions of using self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom.

Overall, the analysis of Group 2’s perceptions of using self-produced videos (SCVs) as a learning tool in the EFL flipped classroom also revealed both positive and negative results. On the positive side, students praised SCVs as an effective and engaging vocabulary teaching tool. They found this method more manageable and interesting than traditional approaches, with some suggesting its broader adoption in educational settings. SCVs were also credited with enhancing vocabulary acquisition, as students appreciated the combination of visual and audio elements, their accessibility enabling them to review materials repeatedly, and the enjoyable learning experience. Peer-created videos boosted students’ motivation and engagement, leading to better learning outcomes. They highlighted the innovative use of technology, viewing it as an alternative to outdated traditional methods. While SCVs were valued positively, however, many students still suggested combining them with traditional techniques for greater effectiveness, proposing a blend of video-making and other interactive methods. On the negative side, some students raised concerns about the excessive vocabulary load, noting the challenge of learning too many new words at once. Deadline issues also emerged, with delays in video uploads affecting preparation times for subsequent groups. Additionally, some students found it difficult to retain part of the new vocabulary over time, which they considered a drawback of the approach. Thus, while SCVs were acknowledged as a valuable and engaging learning tool, students highlighted several areas for improvement to enhance the practicality and overall effectiveness of the approach.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study explores the effectiveness of student-created videos (SCVs) in enhancing vocabulary acquisition within a flipped classroom setting for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners. It aims to provide new insights into how innovative video-based methodologies impact vocabulary learning compared to traditional teacher-led methods based on direct instruction. The findings from both quantitative and qualitative analyses offer significant insights into the effectiveness of SCVs and reveal notable differences in student perceptions based on their roles as either video creators or users.

Quantitative analysis demonstrated that SCVs have a substantial impact on vocabulary acquisition. Group 1, which created and utilized SCVs, showed the most remarkable improvement in vocabulary scores, with a mean post-test score of 87.69 and a gain of 62.13 points from their pre-test. This significant increase suggests that the dual involvement in creating and using SCVs led to a deeper and more effective learning experience. Conversely, Group 2, which only used the SCVs produced by Group 1, achieved a mean post-test score of 83.12, reflecting a smaller yet notable improvement of 58.18 points. While the use of SCVs was beneficial, the slightly lower progress compared to Group 1 indicates that the act of creating the videos provides additional educational benefits. The control group, Group 3, which relied solely on conventional teaching techniques without using video, had the lowest post-test score of 79.64 and a gain of 54.14 points, highlighting the limitations of conventional methods in achieving the same level of vocabulary acquisition as the SCV approaches. These results underscore the value of incorporating SCVs into the curriculum, particularly when students are actively involved in their creation. Active engagement in video production appears to enhance vocabulary retention and application more effectively than passive content consumption (Akdeniz, 2017; Anas, 2019; Stanley & Zhang, 2018).

The qualitative analysis provides a nuanced understanding of how students perceive the process and outcomes of using SCVs. The perceptions of Group 1 (video creators) and Group 2 (video users) reveal both the strengths and limitations of this approach. Students in Group 1 experienced several benefits from their role as video creators. They reported substantial gains in vocabulary acquisition through extensive engagement with new words during video production. The repetitive use and context-based learning facilitated by the creation process were noted as key factors in their enhanced vocabulary retention. Creators also valued the development of digital literacy skills as a significant advantage of the project. The practical skills gained in video editing and production were seen as valuable beyond the scope of vocabulary learning. Despite these benefits, video creators faced challenges, particularly the time-consuming nature of video production and difficulties in achieving high-quality outputs. Issues such as teamwork delays and the extensive time required for video creation were cited as drawbacks. These findings align with previous research suggesting that while creating multimedia content can enhance learning, it also demands significant time and effort (Guenier, 2023; Olivier, 2019).

Students in Group 2 (video users) also recognized the effectiveness of the videos in enhancing vocabulary acquisition. They appreciated the combination of visual and auditory elements, which made learning more engaging. The ability to review the videos multiple times was particularly valued. However, video users faced challenges related to vocabulary overload and retention. The large volume of new vocabulary introduced in each lesson and the difficulty in retaining it were noted as significant issues. Additionally, users expressed a preference for combining SCVs with traditional methods to balance the learning experience, suggesting that a hybrid approach might offer the most comprehensive benefits. These challenges echo findings from similar studies, which indicate that while multimedia resources can enhance engagement, they must be carefully designed to avoid cognitive overload and ensure effective learning (Olivier, 2019; Torrado Cespón & Bárcena Toyos, 2025).

The comparative analysis of the perceptions of video creators and users highlights several key insights. Video creators benefited from deeper engagement with the content and the development of additional skills, which contributed to more significant vocabulary gains. In contrast, video users, while still finding the SCVs effective, did not experience the same level of engagement or skill development. This suggests that the act of creating content provides additional cognitive and motivational benefits that are not fully realized through passive content consumption alone. This finding is consistent with research indicating that active learning strategies, such as creating educational content, can lead to better retention and understanding (Anas, 2019; Bobkina & Domínguez Romero, 2020; Bobkina et al., 2020).

The challenges faced by both groups—such as vocabulary overload for users and production difficulties for creators—suggest that while SCVs are a powerful tool, their implementation needs careful consideration. Addressing these challenges through improved planning and integration with conventional methods could optimize the effectiveness of SCVs in EFL classrooms. For instance, clearer guidelines for video production, such as specific recommendations on video quality (resolution, framerate, audio standards) and balanced use of effects, along with manageable vocabulary loads and glossaries for complex terms, could help mitigate some of the issues faced by both SCVs creators and users (Herrero & Vanderschelden, 2019).

Several pedagogical implications arise from these findings. Combining SCVs with traditional teacher-led methods, such as direct instruction or repetition and practice, could enhance vocabulary learning by leveraging the strengths of both approaches, providing a more comprehensive learning experience. Additionally, keeping SCVs concise can cater to students’ shorter attention spans, ensuring that videos remain engaging and effective. A blended approach, incorporating both SCVs and conventional teaching techniques appears to offer the most balanced benefits, addressing both the cognitive and motivational needs of students. Educators should consider integrating SCVs with other innovative methods and digital tools to further optimize vocabulary acquisition and retention (Hafour, 2022; Hawley & Allen, 2018). Furthermore, creating a repository of SCVs over time, rather than attempting to produce all videos within a single academic year, could be a viable solution to manage the workload and ensure high-quality outputs.

To conclude, several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size of 47 students, drawn from a single Translation and Translation Studies course at one institution, limits the generalizability of the findings to broader EFL populations and varied educational contexts. The use of convenience sampling and the absence of random assignment introduce the possibility of pre-existing group differences, which may have influenced the observed outcomes. Furthermore, the study’s short duration, limited qualitative data, he single-instructor design, and the specific course setting constrain the broader applicability of the results. Additional factors, such as the potential influence of the Hawthorne effect and the lack of control over external variables, may also affect the internal validity of the findings. Future research should aim to address these limitations by employing larger and more diverse samples, incorporating random assignment, and refining video production processes to strengthen the pedagogical effectiveness and scalability of student-generated video materials in EFL contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and J.B.; Funding acquisition, E.D.R.; Investigation, S.B., J.B. and E.D.R.; Methodology, S.B.; J.B. and E.D.R.; Writing—original draft, J.B. and S.B.; Writing—review & editing, E.D.R.; Project administration—E.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)/European Regional Development Fund [Grant Number PID2021-125327NB-100; Project Number 4030263] and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Gobierno de España (MCIN)/Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [Grant Number PID2021-125327NB-100; Project Number 4030263].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data have been anonymized but are not publicly available because of the privacy issues related to the qualitative nature of it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Sample Vocabulary Assessment Items: Pre-Test and Post-Test

| Word Recognition |

Choose the correct word that matches the given definition or context.

|

| Meaning Recognition |

Choose the correct meaning for the given word.

|

| Definition-Based Word Recall |

Write the word that matches the given definition.

|

| Translation-Based Word Recall |

Translate the following Russian terms into English.

|

These types of items incorporate various cognitive skills, including recognition, recall, and translation, and are tailored to test both Passive and Active Vocabulary knowledge.

Appendix B. Interview Questions

| For group 1 (video creators) |

|

| For group 2 (consumers) |

|

Appendix C. Example of Student-Created Videos

Example 1. Student-created video on Crime and Punishment.

Crime and Punishment [Video]. https://youtu.be/07ts74w7CPU (accessed on 1 April 2025)

Example 2. Student-created video on Art and Painting.

Art Painting [Video]. https://youtu.be/lftId_zjRcM (accessed on 1 April 2025)

Example 3. Student-created video on Music.

Music [Video]. https://youtu.be/EeDm4v3hekw (accessed on 1 April 2025).

References

- Abdulrahman, T. R., & Basalama, N. (2019). Promoting students’ motivation in learning English vocabulary through a collaborative video project. Celt: A Journal of Culture, English Language Teaching & Literature, 19(1), 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, I., Ananyina, A., & Shishmolina, E. (2013). Challenges in teaching Russian students to speak English. American Journal of Educational Research, 1(3), 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, N. (2019). A study on vocabulary-learning problems encountered by BA English majors at the university level of education. Arab World English Journal, 10(3), 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, N. Ö. (2017). Use of student-produced videos to develop oral skills in EFL classrooms. International Journal on Language, Literature and Culture in Education, 4(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al Qasmi, A. M. B., Al Barwani, T., & Al Seyabi, F. (2022). Flipped classrooms and their effect on Omani students’ vocabulary achievement and motivation towards learning English. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 16(2), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Seghayer, K. (2001). The effect of multimedia annotation modes on L2 vocabulary acquisition: A comparative study. Language Learning & Technology, 5(1), 202–232. [Google Scholar]

- Anas, I. (2019). Behind the scene: Student-created video as a meaning-making process to promote student active learning. Teaching English with Technology, 19(4), 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Argudo-Serrano, J., Albán-Neira, M. L., Argudo Garzon, A. L., Sánchez Rodríguez, J. A., & Orellana Parra, N. P. (2024). Educational innovation: Teacher- and student-made videos to enhance English proficiency at university level. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(4), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, G., & Seyyedrezaie, S. H. (2013). Language learning and vocabulary: A review. Journal of Humanities Insights, 1(3), 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. International Society for Technology in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bobkina, J., & Domínguez Romero, E. (2020). Exploring the perceived benefits of self-produced videos for developing oracy skills in digital media environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(7), 1384–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkina, J., Domínguez Romero, E., & Gómez Ortiz, M. (2020). Educational mini-videos as teaching and learning tools for improving competence in EFL/ESL university students. Teaching English with Technology, 20(3), 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. S. (1983). Child’s talk: Learning to use language. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-H. (2023). Is a video worth a thousand words? Enhancing second language reading comprehension through video-based e-book design and presentation. English Teaching & Learning, 47(1), 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, E. (1969). Audiovisual methods in teaching (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, J.-M. (2022). Enjoyment. In S. Li, P. Hiver, & M. Papi (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and individual differences (pp. 190–206). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2019). Learning English through out-of-school exposure: How do word-related variables and proficiency influence receptive vocabulary learning? Language Learning, 70(2), 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, S., Nozari, F., & Salman, A. R. (2022). Investigating the effects of flipped vocabulary learning via an online dictionary on EFL learners’ listening comprehension. Smart Learning Environments, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, M. (2014). Extending the flipped classroom model: Developing second language writing skills through student-created digital videos. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(5), 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, K. S. (2004). The underestimated importance of vocabulary in the foreign language classroom. CLEAR News, 8(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gersten, R., & Baker, S. (2000). What we know about effective instructional practices for English-language learners. Exceptional Children, 66(4), 454–470. [Google Scholar]

- Guenier, A. (2023). Student initiative of producing their own mini videos for language learning. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 13(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, C. A., & Miller, L. (2011). Fostering learner autonomy in English for science: A collaborative digital video project in a technological learning environment. Language Learning & Technology, 15(3), 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hafour, M. F. (2022). Interactive digital media assignments: Effects on EFL learners’ overall and micro-level oral language skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(4), 986–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T., Wang, Z., & Ardasheva, Y. (2021). Technology-assisted vocabulary learning for EFL learners: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14, 645–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, R., & Allen, C. (2018). Student-generated video creation for assessment: Can it transform assessment within higher education? International Journal for Transformative Research, 5(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, C., & Vanderschelden, I. (Eds.). (2019). Using film and media in the language classroom. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H.-T. (2015). Intentional vocabulary learning using digital flashcards. English Language Teaching, 8(10), 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2022). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 29.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A. (2019). Implementing audio-visual materials (videos), as an incidental vocabulary learning strategy, in second/foreign language learners’ vocabulary development: A current review of the most recent research. Journal on English Language Teaching, 9(2), 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kost, C. R., Foss, P., & Lenzini, J. J. (1999). Textual and pictorial glosses: Effectiveness on incidental vocabulary growth when reading in a foreign language. Foreign Language Annals, 32(1), 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovsh, E. (2020). Grammar aspect of English and German acquisition in Russian medium. E3S Web of Conferences, 210, 21005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens, A. H. (2010). Incidental foreign language acquisition from media exposure. Learning, Media and Technology, 35(1), 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A. M. Y. (2014). Authentic language input through audiovisual technology and second language acquisition. SAGE Open, 4(3), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, E., & Muñoz, C. (2013). The influence of out-of-school exposure to English language media on learners’ vocabulary knowledge. Language Learning Journal, 41(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. (2022). Implication from Incidental and Intentional Learning in Taking up a Foreign Language. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th international conference on humanities education and social sciences (ICHESS 2021). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2021). The past, present, and future of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Educational Psychology Review, 36, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnychenko, A. (2024). Challenges in EFL vocabulary acquisition in Russian universities. Journal of Language and Education, 10(1), 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mitterer, H., & McQueen, J. M. (2009). Foreign subtitles help but native-language subtitles harm foreign speech perception. PLoS ONE, 4(11), e7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero Perez, M., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Desmet, P. (2013). Captioned video for L2 listening and vocabulary learning: A meta-analysis. System, 41(3), 720–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, F., & Asadnia, F. (2024). Exploring the effect of EFL students’ self-made digital stories on their vocabulary learning. System, 120, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J. (2019). Short instructional videos as multimodal open educational resources in a language classroom. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 28(4), 381–409. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual-coding approach. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio, A. (2010). Dual coding theory and education. In J. M. Clark, & A. Paivio (Eds.), Educational psychology review (Vol. 3, pp. 149–170). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E. (2018). The effect of out-of-class exposure to English language media on learners’ vocabulary knowledge. ITL—International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 169(1), 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E., Heynen, E., & Puimège, E. (2016). Learning vocabulary through audiovisual input: The differential effect of L1 subtitles and captions. System, 63, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E., & Webb, S. (2018). Incidental vocabulary acquisition through viewing l2 television and factors that affect learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(3), 551–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, J. L., & Jones, L. C. (2005). Multimedia learning in second language acquisition. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 467–488). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, D. I., Fitriati, S. W., Yuliasri, I., & Waluyo, B. (2024). Flipped classroom with gamified technology and paper-based method for teaching vocabulary. Asian Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B. L., Cui, Y., Kao, C.-W., & Thomas, N. (2022). Vocabulary acquisition through viewing captioned and subtitled video: A scoping review and meta-analysis. Systems, 10(5), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M. P. H. (2018). The images in television programs and the potential for learning unknown words. ITL—International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 169(1), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M. P. H., & Webb, S. (2011). Narrow viewing: The vocabulary in related television programs. TESOL Quarterly, 45(4), 689–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M. P. H., & Webb, S. (2017). Incidental vocabulary learning through viewing television. ITL—International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 171(2), 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J. (2017). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyashina, E. (2020). ‘Incidental + intentional’ vs ‘intentional + incidental’ vocabulary learning: Which is more effective? Complutense Journal of English Studies, 28, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Student-produced videos can enhance engagement and learning in the online environment. Online Learning Journal, 22(2), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2015). Sociocultural theory in second language education: An introduction through narratives. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, F. M. (2022). Incidental L2 vocabulary learning from viewing captioned videos: Effects of learner-related factors. System, 105, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado Cespón, M., & Bárcena Toyos, P. (2025). An example of gamification for pre-service teachers in online higher education: Methods, tools, and purpose. Digital Education Review, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, S., & Rodgers, M. P. H. (2009). Vocabulary demands of television programs. Language Learning, 59(2), 335–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S., Uchihara, T., & Yanagisawa, A. (2023). How effective is second language incidental vocabulary learning? A meta-analysis. Language Teaching, 56(2), 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas, I. (2009). Multimedia glosses and their effect on L2 text comprehension and vocabulary learning. Language Learning & Technology, 13(2), 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yawiloeng, R. (2020). Second language vocabulary learning from viewing video in an EFL classroom. English Language Teaching, 13(7), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A., & Trainin, G. (2021). A meta-analysis examining technology-assisted L2 vocabulary learning. ReCALL, 34, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., & Wu, X. (2024). The impact of internal-generated contextual clues on EFL vocabulary learning: Insights from EEG. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1332098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).