A Comparative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Reading Instruction and Their Confidence in Supporting Struggling Readers: A Study of India and England

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. English Language Reading in India

3. Reading Outcomes in India

Teacher Preparation in India

4. Reading Instruction and Teacher Preparation in England

5. Study Purpose

6. Research Questions

- To what extent are preservice teachers in England and India familiar with foundational reading knowledge, and what are the differences in phonics knowledge between these two groups?

- How well prepared are preservice teachers to teach phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and reading comprehension strategies, and what are the differences in pedagogical knowledge between English and Indian preservice teachers?

- What is the level of confidence that preservice teachers report in teaching reading to students experiencing reading difficulties in inclusive classroom settings, and what are the differences between English and Indian preservice teachers?

7. Methods

7.1. Sample

7.2. Survey Instrument

7.2.1. Section 1: Demographic Information

7.2.2. Section 2: Knowledge of Reading-Related Constructs

7.2.3. Section 3: Knowledge of Reading Instruction

7.2.4. Section 4: Confidence in Supporting Students Experiencing Reading Difficulties

8. Analytic Approach

9. Results

9.1. To What Extent Are Preservice Teachers in England and India Familiar with Foundational Reading Knowledge, and What Are the Differences in Phonics Knowledge Between These Two Groups?

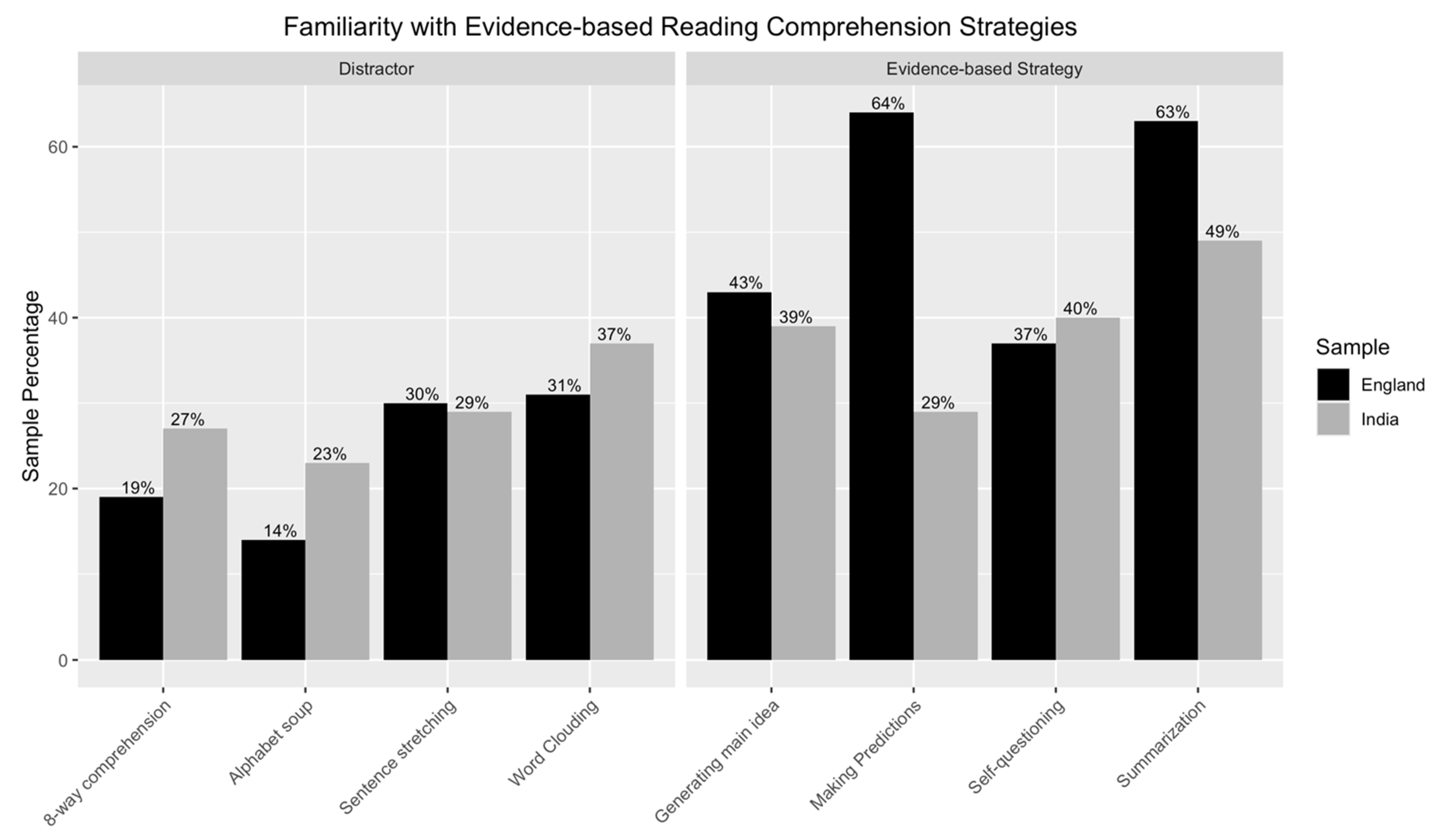

9.2. How Well Prepared Are Preservice Teachers with Pedagogical Practices to Teach Phonemic Awareness, Phonics, Reading Fluency, Vocabulary, and Reading Comprehension Strategies, and What Are the Differences in Pedagogical Knowledge Between English and Indian Preservice Teachers?

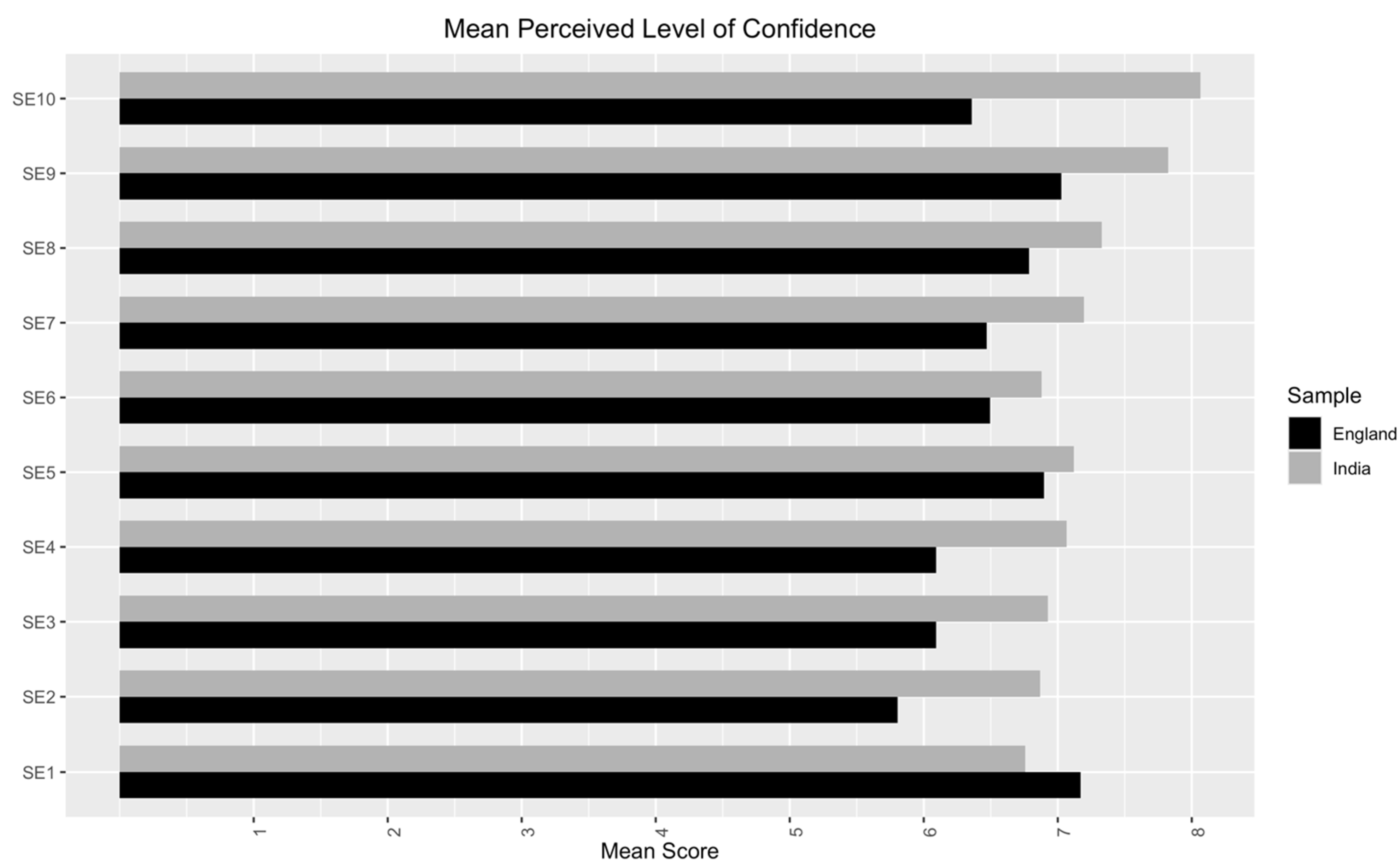

9.3. What Is the Level of Confidence That Preservice Teachers Report in Teaching Reading to Students Experiencing Reading Difficulties in Inclusive Classroom Settings, and What Are the Differences Between England and Indian Preservice Teachers?

10. Discussion

10.1. Foundational Reading Knowledge

10.2. Pedagogical Preparedness in Teaching Reading

10.3. Current University Coursework in Reading and Inclusive Practices

10.4. Confidence in Supporting Students Experiencing Reading Difficulties

10.5. Implications for Teacher Education Program and Policy

10.6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Your age _____ (in years)

- Gender _______ M/F/non-binary

- Please specify the name of the higher education institution (i.e., university) where you are currently enrolled. ________________

- Programmes ________ (e.g., BA in ….)

- Programmes Year of Study _______ (first, second, final)

- Do you have any past teaching experience in a school? (Y/N)

- If yes, you worked as a

- Instructional aide/teaching assistant

- Teacher

- School administrator

- Other

- What age group of children do you plan to teach after graduation?

- Early childhood (Nursery to Reception);

- Primary school (Years 1 to 2—Key Stage 1),

- Later years (Years 4 or later, Key Stage 2 or later)

- What subjects are you interested in teaching? (Select all that apply)

- English

- Science

- Social studies/history

- Art

- Music

- Physical education

- Languages other than English

- Special Education

- Other (Please specify) _______

- Please indicate the number of modules you have taken during your Bachelor’s programmes of study that focused on teaching reading to primary or pre-primary age students.

- One module

- Two modules

- Three or more modules

- None of the modules focused on how to teach reading

- If wug is a word, the letter ‘u’ would probably sound like ‘u’ in:

- cute

- duck

- about

- I am not sure

- If flek is a word, then the letter ‘e’ would probably sound like ‘e’ in

- bend

- her

- me

- I am not sure

- A combination of two or three consonants that are pronounced separately, each keeping its own unique sound, is called

- Silent consonant

- Consonant blend

- Schwa sound

- I am not sure

- Choose the word below that has a consonant blend in it:

- Black

- Ship

- What

- I am not sure

- How many individual speech sounds or phonemes are represented by the word cat?

- 2

- 3

- 4

- I am not sure

- How many individual speech sounds or phonemes are represented by the word goat?

- 3

- 4

- 5

- I am not sure

- Which of the following pairs of words begin with the same sound

- Cat and Kite

- Chess and chorus

- Gold and Gentle

- I am not sure

- Which of the following pairs of words contain the same vowel sounds-

- Good and Zoom

- Foot and Boot

- True and You

- I am not sure

- How many syllables are in the word ‘table’?

- One

- Two

- Five

- I am not sure

- How many syllables are in the word ‘chart’?

- One

- Two

- Five

- I am not sure

- How many syllables are in the word ‘basketball’

- Two

- Three

- Nine

- I am not sure

- Which of these words is a compound word?

- University

- Computer

- Firefly

- I am not sure

- What is a CVC word?

- A single syllable word with a consonant-vowel-consonant pattern.

- A nonsense word that is made up of a consonant, a vowel, and a consonant.

- A word that is made up of the smallest unit of sound in a language, called a phoneme.

- I am not sure

- How would you assess and monitor students’ progress in word reading skills?

- Regular tests or quizzes

- Through observing students during literacy activities

- Informal reading assessments

- Combination of the above

- I am not sure

- Phonics instruction typically starts with

- Vowel sounds

- Consonant sounds

- Schwa sound

- All of the above

- I am not sure

- In early literacy, what is phonemic awareness?

- Understanding letter-sound correspondence

- Identifying rhyming words

- Recognising individual sounds in spoken words

- All of the above

- I am not sure

- Which activities or strategies would you use to develop phonemic awareness in preschool/kindergarten children?

- Reading words in isolation

- Recognising initial or final sounds in spoken words

- Printing or writing letters

- All of the above

- I am not sure

- Which of the below is one way to teach phonemic awareness skills to preschool/kindergarten children?

- Have students look at a picture of hat and segment each sound by clapping

- Have students choose rhyming words from word cards

- Have students read as many words as possible in one minute

- Have students read words from words cards to their partner

- I am not sure

- How would you assess students’ phonemic awareness skills?

- Asking them to orally manipulate sounds in words

- Administering formal assessments

- Observing how students read unknown or pseudo words

- All of the above

- I am not sure

- What is reading fluency? It is the ability to …

- read independent words accurately

- read with speed and accuracy

- comprehend and understand the meaning of text

- write fluently and coherently

- I am not sure

- What are some ways in which teachers can help students become fluent readers?

- Model fluent reading

- Repeated reading

- Assisted reading with audiobooks

- All of the above

- I am not sure

- How can teachers assess students reading fluency?

- Check to see which fonts students can read in best

- Check students’ vision

- Check the number of words students can read correctly in a minute

- Check if students can memorise and recite the passage and record the number of ideas they recall accurately

- I am not sure

- Pairing students who struggle to read fluently with peers who read more fluently during reading fluency activities can help improve struggling readers’ reading fluency.

- True

- False

- No past studies have explored peer impact on reading fluency

- I have never heard about students working in pairs before

- I am not sure

- You are a primary school teacher and today you are introducing a new vocabulary word “amiable” to your students. Which of the below methods would you use to first introduce this word to ensure that all students understand its meaning?

- Ask students if they know what the word means

- Explain the meaning of the word in everyday language

- Ask students to read a definition from the dictionary

- Have students memorise the meaning of the new word

- I am not sure

- Which of the following options best describes contextual analysis in vocabulary instruction?

- A method of breaking down words into their individual sounds to determine their meaning.

- An approach that emphasises the use of synonyms and antonyms to understand word meanings.

- The process of using surrounding text or clues to infer the meaning of unfamiliar words.

- A strategy that focuses on teaching word origins and etymology to expand vocabulary knowledge.

- I am not sure

- Which of the following options best describes morphemic analysis in vocabulary instruction?

- An approach that encourages students to use gestures and physical movements to act out and learn new vocabulary.

- The process of memorising word definitions through repetition.

- An approach in which students are taught to make use of morphograms to understand the morpheme-grapheme relationship.

- An approach that involves teaching students to analyse the structure and meaning of words by examining the smallest meaningful parts of words.

- I am not sure

- Which of the following options best describes the effectiveness of teaching prefixes to support students’ vocabulary growth? For example, the prefix “re” means again as in resell or to sell again.

- Teaching Latin and Greek prefixes has no impact on students’ vocabulary development.

- Teaching Latin and Greek prefixes is only beneficial for advanced learners.

- Teaching Latin and Greek prefixes significantly enhances students’ vocabulary growth.

- Teaching Latin and Greek prefixes is a time-consuming strategy with limited benefits.

- I am not sure

- What is the Simple View of Reading?

- Reading comprehension is simply dependent on decoding skills

- Reading comprehension is a combination of decoding and language comprehension skills

- Reading comprehension is viewed as a performance in fluency and automaticity in reading

- Reading comprehension is viewed as a combination of reading speed and level of focus to understand the text.

- I am not sure

- Which of the following options best describes reading comprehension strategies?

- Techniques used to decode words and improve reading fluency.

- Strategies to enhance vocabulary and word recognition skills.

- Methods to improve grammar and reading proficiency

- Approaches to understand and interpret the meaning of written text.

- I am not sure

- Choose all of the below that are evidence-based reading comprehension strategies that you could teach students to help support their comprehension of the text:

- Summarisation

- Generating main idea

- Self-questioning

- Making predictions

- 8-way comprehension

- Alphabet soup

- Sentence stretching

- Word clouding

- I have never heard of these before

- Which of the following options best describes reciprocal teaching?

- A strategy in which students take turns acting as the teacher to facilitate group discussions and comprehension monitoring.

- A teaching method that focuses on individualised instruction for struggling readers

- An approach that emphasises the use of visual aids and graphic organisers to enhance comprehension.

- A technique that promotes the development of reading comprehension through peer work

- I am not sure

- Which of the below is a way to assess students’ level of reading comprehension?

- Administering a timed reading comprehension test to measure accuracy and speed.

- Asking students to retell or summarise the main idea and details of the text.

- Conducting a vocabulary quiz to assess students’ comprehension of word meanings

- Observing students’ comprehension of the text during guided reading sessions

- I am not sure

- Identifying struggling readers in your mainstream classroom

- Selecting appropriate strategies for supporting the needs of struggling readers

- Using assessment data to inform your reading instruction for struggling readers

- Implementing effective educational practices to support reading development for struggling readers in your mainstream classroom

- Collaborating with specialists or support staff to address the needs of struggling readers

- Differentiating instruction to meet the needs of struggling readers

- Using various lesson modifications to ensure struggling readers can access the curriculum

- Implementing accommodations to support students’ diverse learning needs

- Motivating struggling readers to engage with reading tasks

- Involving parents or guardians in supporting reading development of struggling readers

- 1 module

- 2 modules

- 3 or more modules

- None of the modules’ core focus was on inclusive education

References

- Adamson, B. (2012). International comparative studies in teaching and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, T., Eklund, K., Eloranta, A. K., Närhi, V., Korhonen, E., & Ahonen, T. (2019). Associations between childhood learning disabilities and adult-age mental health problems, lack of education, and unemployment. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 52(1), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASER Centre. (2023). Annual status of education report (rural) 2022. Aser Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blackorby, J., & Wagner, M. (1996). Longitudinal postschool outcomes of youth with disabilities: Findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study. Exceptional Children, 62(5), 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, J. F., Correnti, R., Phelps, G., & Zeng, J. (2009). Exploration of the contribution of teachers’ knowledge about reading to their students’ improvement in reading. Reading and Writing, 22(4), 457–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L., Reggio, K., Shaywitz, B. A., Holahan, J. M., & Shaywitz, S. E. (2021). Dyslexia in incarcerated men and women. Journal of Correctional Education, 72(2), 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. K., Helfrich, S. R., & Hatch, L. (2017). Examining preservice teacher content and pedagogical content knowledge needed to teach reading in elementary school. Journal of Research in Reading, 40(3), 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooc, N. (2023). National trends in special education and academic outcomes for English learners with disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 57(2), 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, H., & Valdera Gil, F. (2015). Student teachers’ perceptions of feedback as an aid to reflection for developing effective practice in the classroom. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(4), 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M., & Tikly, L. (2004). Postcolonial perspectives and comparative and international research in education: A critical introduction. Comparative Education, 40(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A. E., Perry, K. E., Stanovich, K. E., & Stanovich, P. J. (2004). Disciplinary knowledge of K-3 teachers and their knowledge calibration in the domain of early literacy. Annals of Dyslexia, 54, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dados, N., & Connell, R. (2012). The global south. Contexts, 11(1), 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J. (2024). The academic achievement gap between students with and without special educational needs and disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J. (2025). Achievement gaps for English learners with disabilities. Learning and Instruction, 96, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J., & Williams, K. J. (2021). Self-questioning strategy for struggling readers: A synthesis. Remedial and Special Education, 42(4), 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. (2011). Teachers’ standards. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teachers-standards (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Department for Education. (2014, March 21). National curriculum and assessment from September 2014: Information for schools. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-and-assessment-information-for-schools (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Department for Education. (2023, March 10). Validation of systematic synthetic phonics programmes: Supporting documentation. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/phonics-teaching-materials-core-criteria-and-self-assessment/validation-of-systematic-synthetic-phonics-programmes-supporting-documentation (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Department for Education. (2024, April 5). Initial teacher education (ITE) inspection framework and handbook. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook-for-september-2023 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Double, K. S., McGrane, J. A., Stiff, J. C., & Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2019). The importance of early phonics improvements for predicting later reading comprehension. British Educational Research Journal, 45(6), 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endow, T. (2018). Inferior outcomes: Learning in low-cost English-medium private schools—A survey in Delhi and National Capital Region. Indian Journal of Human Development, 12(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A. M., & Roberts, G. (2012). High school dropouts: Interactions between social context, self-perceptions, school engagement, and student dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE2016-4008). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: http://whatworks.ed.gov (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Williams, J. P., & Baker, S. (2001). Teaching reading comprehension strategies to students with learning disabilities: A review of research. Review of Educational Research, 71(2), 279–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. (Ed.). (2021). Teaching core practices in teacher education. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hikida, M., Chamberlain, K., Tily, S., Daly-Lesch, A., Warner, J. R., & Schallert, D. L. (2019). Reviewing how preservice teachers are prepared to teach reading processes: What the literature suggests and overlooks. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J., Stiff, J., Cadwallader, S., Lee, G., & Kayton, H. (2023). PISA 2022: National report for England. Research report. UK Department for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jhingran, D. (2009). Hundreds of home languages in the country and many in most classrooms: Coping with diversity in primary education in India. Social Justice Through Multilingual Education, 250, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen, U., Niemi, P., Aunola, K., & NURMI, J. E. (2004). Development of reading skills among preschool and primary school pupils. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, K. T., & Schwab, S. (2020). Differentiation and individualisation in inclusive education: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Human Resource Development Government of India. (2020). National education policy 2020. Available online: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Mullis, I. V. S., von Davier, M., Foy, P., Fishbein, B., Reynolds, K. A., & Wry, E. (2023). PIRLS 2021 international results in reading. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, R. (2021, July 3). 26% of schoolkids in English medium; nearly 60% in Delhi. The Times of India. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/26-of-schoolkids-in-english-medium-nearly-60-in-delhi/articleshow/84082483.cms#:~:text=More%20than%20a%20quarter%20of,over%2042%25%20of%20total%20enrolment (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- National Council of Educational Research and Training [NCERT]. (2019). National achievement survey 2017. NCERT.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training [NCERT]. (2022). The national curriculum framework for foundational years. NCERT.

- Ofsted. (2024). Initial teacher education inspection framework and handbook. Ofsted. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Piasta, S. B., Connor, C. M., Fishman, B. J., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Teachers’ knowledge of literacy concepts, classroom practices, and student reading growth. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(3), 224–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podhajski, B., Mather, N., Nathan, J., & Sammons, J. (2009). Professional development in scientifically based reading instruction: Teacher knowledge and reading outcomes. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(5), 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Pant, A., & Singal, N. (2013). Research ethics in comparative and international education: Reflections from anthropology and health. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 43(4), 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J. (2006). Independent review of the teaching of early reading. DfES Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M. L., Burnham, T. J., Catalana, S. M., & Waters, T. (2019). The impact of reflective practice on teacher candidates’ learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(2), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E., Lake, C., Davis, S., & Madden, N. A. (2011). Effective programs for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. Educational Research Review, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snigdha, A. (2021, June 3). UDISE+ Report: More than 42% children study in Hindi, over 26% in English. NDTV. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, E. A., Park, S., & Vaughn, S. (2019). A review of summarizing and main idea interventions for struggling readers in grades 3 through 12: 1978–2016. Remedial and Special Education, 40(3), 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, W. J. (2004). Fluency and comprehension gains as a result of repeated reading: A meta-analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 25(4), 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, J., Mukhopadhyay, L., Balasubramanian, A., Tamboli, V., & Tsimpli, I. (2022). How ready are Indian primary school children for English medium instruction? An analysis of the relationship between the reading skills of low-SES children, their oral vocabulary and English input in the classroom in government schools in India. Applied Linguistics, 43(4), 746–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020: Inclusion and education: All means all. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2019). A world ready to learn: Prioritizing quality early childhood education. United Nations Children’s Fund. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/a-world-ready-to-learn-report/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Washburn, E. K., Binks-Cantrell, E. S., & Joshi, R. M. (2013). What do preservice teachers from the USA and the UK know about dyslexia? Dyslexia, 20(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washburn, E. K., Binks-Cantrell, E. S., Joshi, R. M., Martin-Chang, S., & Arrow, A. (2016). Preservice teacher knowledge of basic language constructs in Canada, England, New Zealand, and the USA. Annals of Dyslexia, 66, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, E. K., Joshi, R. M., & Binks Cantrell, E. (2011). Are preservice teachers prepared to teach struggling readers? Annals of Dyslexia, 61, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. (2019). India: Learning poverty brief. In EduAnalytics (issue October). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/brief/learning-poverty (accessed on 11 September 2024).

| n | India | n | England | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age in Years (SD) | 149 | 26.67 (6.79) | 141 | 21.70 (5.41) |

| Female | 131 | 87% | 121 | 85% |

| Year of Study - First | 67 | 45% | 49 | 35% |

| - Second | 59 | 40% | 43 | 30% |

| - Final | 21 | 14% | 42 | 30% |

| - Not reported | 02 | 1% | 07 | 5% |

| Past Teaching Experience - Yes | 55 | 37% | 71 | 50% |

| - No | 93 | 62% | 63 | 45% |

| - Not reported | 01 | 1% | 07 | 5% |

| Qualified Teaching Age Post-Graduation | ||||

| - Primary school | 29 | 19% | 27 | 19% |

| - Secondary school | 86 | 58% | 19 | 14% |

| - All age groups | 31 | 21% | 93 | 66% |

| - Do not plan to teach | 02 | 1% | 02 | 1% |

| - Not reported | 01 | 1% | - | |

| Total Courses Taken on Teaching Reading | ||||

| - One | 66 | 44% | 40 | 29% |

| - Two | 23 | 15% | 34 | 24% |

| - Three or more | 11 | 8% | 58 | 41% |

| - None of the courses focused on teaching reading | 48 | 32% | 09 | 6% |

| - Not reported | 01 | <1% | - | - |

| Total Courses Take on Inclusive Education | ||||

| - One | 55 | 37% | 40 | 28% |

| - Two | 20 | 13% | 46 | 33% |

| - Three or more | 16 | 11% | 27 | 19% |

| - None of the courses focused on inclusive education | 24 | 16% | 08 | 6% |

| - Not reported | 34 | 23% | 20 | 14% |

| Items | α | No. of Items | Min–Max | India | England | Effect Size (d) (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||||

| Phonics Knowledge | 0.81 | 13 | 0–13 | 141 | 7.30 | 3.36 | 140 | 10.60 | 2.05 | −1.18 (−1.43, −0.92) |

| Pedagogical Knowledge | 0.65 | 19 | ||||||||

| - Phonological Awareness | 5 | 0–5 | 130 | 1.56 | 0.99 | 134 | 2.01 | 0.95 | −0.46 (−0.70, −0.21) | |

| - Phonics | 2 | 0–2 | 127 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 134 | 1.45 | 0.64 | −0.89 (−1.14, −0.63) | |

| - Reading Fluency | 4 | 0–4 | 128 | 2.05 | 1.21 | 128 | 2.51 | 1.08 | −0.40 (−0.64, −0.15) | |

| - Vocabulary | 4 | 0–4 | 125 | 1.79 | 1.16 | 125 | 1.91 | 0.98 | −0.11 (−0.35, 0.13) | |

| - Reading Comprehension | 4 | 0–4 | 114 | 1.70 | 1.18 | 121 | 2.13 | 1.02 | −0.39 (−0.64, −0.13) | |

| Self-Reported Confidence to Support Struggling Readers | 0.91 | 10 | 10–100 | 107 | 72.02 | 14.36 | 117 | 65.19 | 12.31 | 0.51 (0.24, 0.77) |

| Phonics Knowledge | % Correct | % Incorrect | % Unsure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | England | India | England | India | England | |

| Item 1 | 57.44 | 95.00 | 29.07 | 4.28 | 13.47 | 0.71 |

| Item 2 | 54.60 | 92.85 | 24.11 | 5.00 | 21.27 | 2.14 |

| Item 3 | 54.60 | 61.42 | 19.14 | 12.14 | 26.24 | 26.42 |

| Item 4 | 50.35 | 59.28 | 28.36 | 20.71 | 21.27 | 20.00 |

| Item 5 | 52.48 | 90.00 | 36.17 | 9.28 | 11.34 | 0.71 |

| Item 6 | 65.95 | 97.85 | 19.85 | 0.71 | 14.18 | 1.42 |

| Item 7 | 75.88 | 87.14 | 17.73 | 11.42 | 6.38 | 1.42 |

| Item 8 | 28.36 | 87.85 | 65.24 | 8.57 | 6.38 | 3.57 |

| Item 9 | 63.82 | 88.57 | 19.14 | 8.57 | 17.02 | 2.85 |

| Item 10 | 46.80 | 57.85 | 36.87 | 37.85 | 16.31 | 4.28 |

| Item 11 | 56.73 | 89.28 | 25.53 | 8.57 | 17.73 | 2.14 |

| Item 12 | 69.50 | 70.71 | 17.02 | 8.57 | 13.47 | 20.71 |

| Item 13 | 53.90 | 82.14 | 15.60 | 7.14 | 30.49 | 10.71 |

| Mean % | 56.19 | 81.53 | 27.22 | 10.99 | 16.58 | 7.47 |

| Pedagogical Knowledge | % Correct | % Incorrect | % Unsure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | England | India | England | India | England | |

| Phonic Item 1 | 62.20 | 82.83 | 35.43 | 16.41 | 2.36 | 0.74 |

| Phonic Item 2 | 22.83 | 61.94 | 60.62 | 26.86 | 16.53 | 11.19 |

| PA Item 1 | 23.07 | 24.62 | 67.69 | 73.13 | 9.23 | 2.23 |

| PA Item 2 | 25.38 | 47.01 | 68.46 | 50.00 | 6.15 | 2.98 |

| PA Item 3 | 47.69 | 72.38 | 37.69 | 22.38 | 14.61 | 5.22 |

| PA Item 4 | 43.84 | 41.04 | 45.38 | 52.23 | 10.76 | 6.71 |

| Fluency Item 1 | 43.75 | 54.68 | 53.90 | 42.96 | 2.34 | 2.34 |

| Fluency Item 2 | 53.12 | 72.65 | 43.75 | 25.00 | 3.12 | 2.34 |

| Fluency Item 3 | 42.18 | 60.93 | 45.31 | 24.21 | 12.50 | 14.84 |

| Fluency Item 4 | 65.62 | 62.50 | 16.40 | 14.06 | 17.96 | 23.43 |

| Vocab Item 1 | 62.40 | 40.00 | 29.60 | 57.60 | 8.00 | 2.40 |

| Vocab Item 2 | 30.40 | 52.00 | 47.20 | 20.80 | 22.40 | 27.20 |

| Vocab Item 3 | 30.40 | 20.00 | 37.60 | 30.40 | 32.00 | 49.60 |

| Vocab Item 4 | 56.00 | 79.20 | 23.20 | 4.80 | 20.80 | 16.00 |

| RC Item 1 | 43.85 | 53.71 | 44.73 | 32.23 | 11.40 | 14.04 |

| RC Item 2 | 30.70 | 55.37 | 57.01 | 38.01 | 12.28 | 6.61 |

| RC Item 4 | 39.47 | 24.79 | 33.33 | 28.09 | 27.19 | 47.10 |

| RC Item 5 | 56.14 | 79.33 | 29.82 | 12.39 | 14.03 | 8.26 |

| Mean % | 41.85 | 52.70 | 44.46 | 33.93 | 13.67 | 13.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniel, J.; Misquitta, R.; Nelson, S. A Comparative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Reading Instruction and Their Confidence in Supporting Struggling Readers: A Study of India and England. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040442

Daniel J, Misquitta R, Nelson S. A Comparative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Reading Instruction and Their Confidence in Supporting Struggling Readers: A Study of India and England. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040442

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniel, Johny, Radhika Misquitta, and Sophie Nelson. 2025. "A Comparative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Reading Instruction and Their Confidence in Supporting Struggling Readers: A Study of India and England" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040442

APA StyleDaniel, J., Misquitta, R., & Nelson, S. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Reading Instruction and Their Confidence in Supporting Struggling Readers: A Study of India and England. Education Sciences, 15(4), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040442