Teaching Accessible Space in Architectural Education: Comparison of the Effectiveness of Simulated Disability Training and Expert-Led Methods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Group A, besides participating in theoretical lectures and design tasks, underwent simulated disability training;

- Group B, besides participating in theoretical lectures and design tasks, participated in expert-led workshops.

- Phase 1: Organization and commencement of the Ergonomics and Designing Spaces for Elderly and Disabled Persons course, including interior design project and theoretical lectures conducted with an ex cathedra modality for two student groups: Group A and Group B;

- Phase 2: Conducting a simulated disability training session in student Group A following the checkup list and concluding with a personal opinion survey. Concluding expert-led workshop in Group B;

- Phase 3: Completion of an interior design project and theoretical lectures conducted with an ex cathedra modality for two student groups: Group A and Group B;

- Phase 4: Conducting an ergonomics knowledge test three months after the course ended in both student Group A and student Group B;

- Phase 5: Comparing the results of the ergonomics knowledge test between student Groups A and B to demonstrate whether sensitization training impacts long-term, three-month-scale learning outcomes.

- Persons moving in a manual wheelchair: Students were required to navigate spaces using a manual wheelchair, simulating the challenges faced by individuals with mobility impairments;

- Persons moving with the help of a crutch: Students experienced moving through different environments while using a crutch, highlighting the difficulties and limitations in mobility for those who require such assistance;

- Blindfolded persons (with blindfolded eyes) moving with the help of a white cane: This scenario involved students being blindfolded and navigating spaces using a white cane, simulating the experience of individuals with visual impairments.

- Using a limited amount of furniture but integrating it in a visually seamless way;

- Dominance of fixed, mounted, or permanently placed furniture against walls, reducing visual chaos and layout changes;

- Introducing rounded, fluid shapes and low furniture adapted to wheelchair height;

- Introducing furniture that is easy to transfer to from a wheelchair or furniture elements that can serve as support (e.g., using a bed frame with suitable parameters for easier transfers from a wheelchair);

- Locating storage spaces at a low height, making them easily accessible and within sight;

- Strictly implementing tables and countertops that accommodate the wheelchair user’s knees;

- Introducing systems allowing the use of high-level storage spaces (wardrobe with modern storage systems with lowering rods; storage systems equipped with pantographs).

- 8.

- Elimination of all thresholds, and leveling floors in all rooms;

- 9.

- Introducing flooring finishing materials with a high anti-slip class and varied textures;

- 10.

- Contrasting color schemes to facilitate orientation for individuals with low vision.

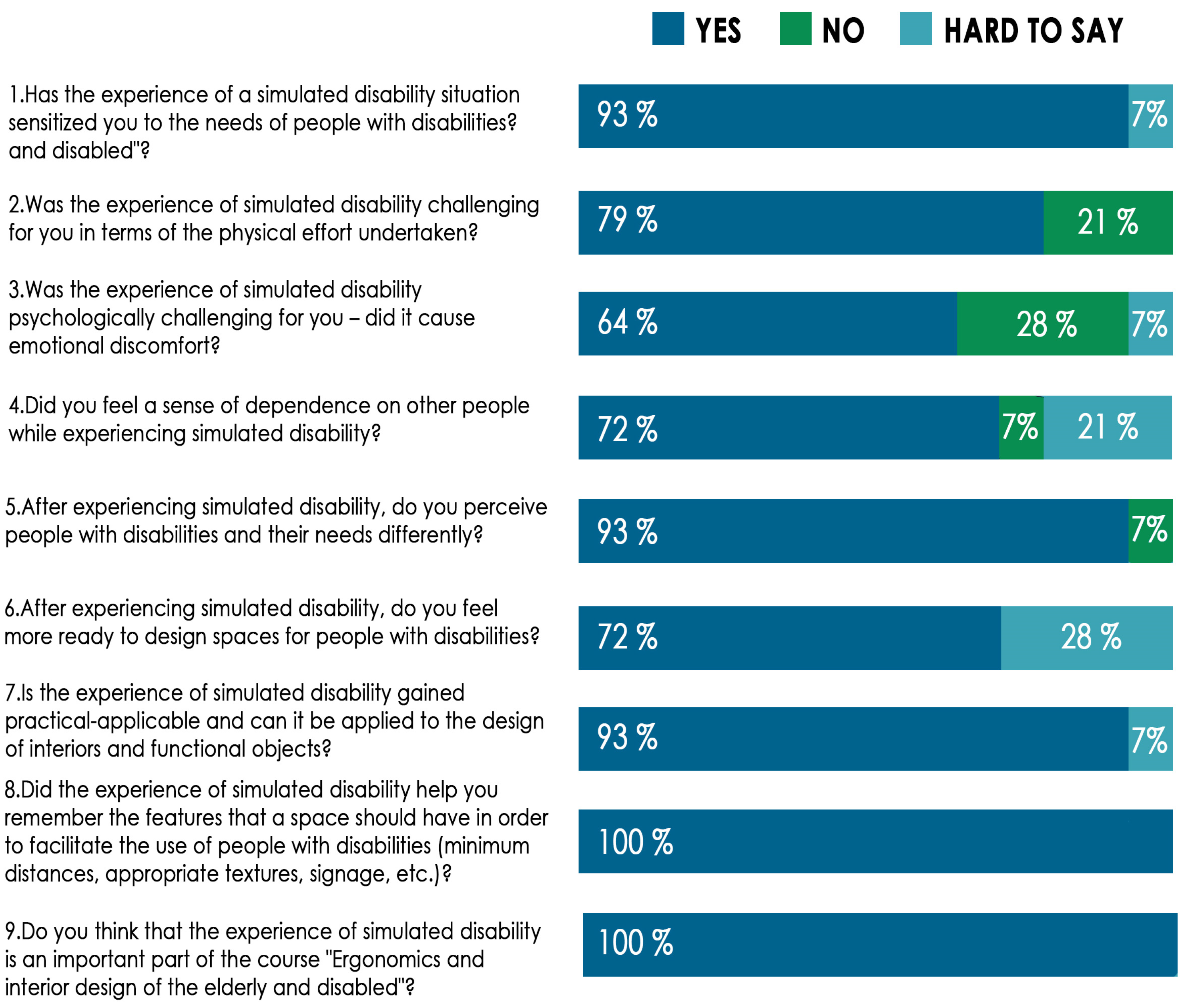

3. Results

- A total of 20% of respondents reported that the experience was challenging in terms of physical effort, indicating the physical demands of navigating spaces with a disability;

- A total of 30% of respondents found the experience to be psychologically difficult, describing it as emotionally uncomfortable. This discomfort likely stemmed from the frustration and limitations they felt while performing daily tasks under simulated disability conditions.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altay, B., & Demirkan, H. (2013). Inclusive design: Developing students’ knowledge and attitude through empathic modelling. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(2), 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. (2013). A Critique of disability/impairment simulations (p. 2013) [Unpublished manuscript]. Available online: https://autistichoya.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/a-critique-of-disability-impairment-simulations.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Burgstahler, S., & Doe, T. (2004). Disability-related simulations: If, when, and how to use them in professional development. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 1(2). Available online: https://www.rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/385/1182 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Douglas, S., Krause, J. M., & Franks, H. M. (2019). Shifting preservice teachers’ perceptions of impairment through disability-related simulations. Palaestra, 33(2), 45. [Google Scholar]

- F. Antonak, R., & Livneh, H. (2000). Measurement of attitudes toward persons with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22(5), 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- French, S. (1992). Simulation exercises in disability awareness training: A critique. Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(3), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, E., & Marini, I. (1996). Simulated disability exercises and their impact on attitudes toward persons with disabilities. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 19(2), 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, J. T. (2000). Simulation as a learning method to facilitate disability awareness. Journal of Experiential Education, 23(1), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrecht, A. L., Steffens, S., Roesner, A. J., Kohal, R. J., Vach, K., & Spies, B. C. (2023). Effects of a disability-simulating learning unit on ableism of final-year dental students—A pilot study. Special Care in Dentistry, 43(6), 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitch, D., Dell, K., & Larkin, H. (2016). Does universal design education impact on the attitudes of architecture students towards people with a disability? Journal Contribution, 16, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, G. (1992). Disability simulations: Logical, methodological and ethical issues. Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(1), 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law of July 19, 2019, on Ensuring Accessibility for Persons with Special Needs, Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1062, as amended. (2019). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190001696 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Lean, J., Moizer, J., Towler, M., & Abbey, C. (2006). Simulations and games: Use and barriers in higher education. Active Learning in Higher Education, 7(3), 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, J., & Goodwin, D. (2014). Negotiated meanings of disability simulations in an adapted physical activity course: Learning from student reflections. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 31(2), 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, J., & Goodwin, D. L. (2013). Pedagogical reflections on the use of disability simulations in higher education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 32(4), 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, W. K. (2019). Teaching embodiment: Disability, subjectivity, and architectural education. The Journal of Architecture, 24(6), 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, M., Bonenberg, A. B., & Barbara, L. (2023). Sensitization of designers to the needs of people with disabilities. Application of experiences in residential interior solutions in Milan. Środowisko Mieszkaniowe/Housing Environment, 45, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. Y. K., & Mak, W. W. (2022). Meta-analysis of studies on the impact of mobility disability simulation programs on attitudes toward people with disabilities and environmental in/accessibility. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0269357. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, J., Marques, B., & Harkness, R. (2020). Simulating impairment through virtual reality. International Journal of Architectural Computing, 18(3), 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- Medola, F. O., Sandnes, F. E., Ferrari, A. L. M., & Rodrigues, A. C. T. (2018). Strategies for developing students’ empathy and awareness for the needs of people with disabilities: Contributions to design education. In Transforming our world through design, diversity and education (Vol. 256, pp. 137–147). IOS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsinszki, S. K., Tanel, N. L., Kowal, J., King, G., Menna-Dack, D., Chu, A., Parker, K., & Phoenix, M. (2023). Delivery and evaluation of simulations to promote authentic and meaningful engagement in childhood disability research. Research Involvement and Engagement, 9(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Modell, S. J., & Mak, S. (2008). A preliminary assessment of police officers’ knowledge and perceptions of persons with disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 46(3), 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Moizer, J., Lean, J., Towler, M., & Abbey, C. (2009). Simulations and games: Overcoming the barriers to their use in higher education. Active Learning in Higher Education, 10(3), 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, K., Calder, A., & Mulligan, H. (2018). Inclusive design in architectural practice: Experiential learning of disability in architectural education. Disability and Health Journal, 11(2), 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nario-Redmond, M. R., Gospodinov, D., & Cobb, A. (2017). Crip for a day: The unintended negative consequences of disability simulations. Rehabilitation Psychology, 62(3), 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R., López, V., Jiménez, M., García-Calvo, T., & Hutzler, Y. (2011). Effects of awareness interventions on children’s attitudes toward peers with a visual impairment. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 34(3), 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccobono, M. (2017). Walking a mile: The possibilities and pitfalls of simulations. Available online: https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/bm/bm17/bm1704/bm170402.htm (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Rotenberg, S., Gatta, D. R., Wahedi, A., Loo, R., McFadden, E., & Ryan, S. (2022). Disability training for health workers: A global evidence synthesis. Disability and Health Journal, 15(2), 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, A. M. (2015). The Perils of playing blind: Problems with blindness simulation and a better way to teach about blindness. Available online: https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/jbir/jbir15/jbir050201.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Soyupak, İ. (2021). Architecture as a matter of inclusion: Constructing disability awareness in architectural education. Periodica Polytechnica Architecture, 52(2), 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchorn, V., Larkin, H., Ang, S., & Hitch, D. (2013). Strategies and effectiveness of teaching universal design in a cross-faculty setting. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(5), 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulated Disability Training | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| 1. Practical Learning Experience Simulated disability training provides a practical, hands-on learning experience that goes beyond theoretical knowledge. It allows participants to engage directly with the physical and emotional aspects of living with a disability; 2. Immediate Feedback Participants can receive immediate feedback on their behavior, decisions, and design choices, allowing them to learn quickly and adjust their approach to better accommodate individuals with disabilities; 3. Heightened Awareness of Accessibility Needs This training can help participants identify potential barriers in their environments that they may not have otherwise considered. By recognizing these barriers, they can work to eliminate or reduce them; 4. Team Building and Collaboration Simulated disability training often involves group activities, promoting teamwork and collaboration among participants as they work together to navigate challenges; 5. Increased Empathy and Awareness By experiencing simulated disabilities, participants can develop a deeper understanding and empathy for people with disabilities. This firsthand experience can help them better appreciate the challenges faced by individuals with disabilities in their daily lives. | 1. Lack of Authentic Experience While simulations can offer insights into specific physical challenges, they fail to capture the broader, everyday lived experiences of people with disabilities, such as the psychological and social barriers they face. These short-term simulations may oversimplify or misrepresent the complexities of living with a disability; 2. Lack of Disability Representation and Input Simulated exercises, if not guided or co-facilitated by people with disabilities, may lack critical perspectives and insights that only those with lived experience can provide. The absence of this direct input can lead to misunderstandings or oversights in how accessibility and inclusivity are taught; 3. Reinforcing Stereotypes Critics contend that simulated disability training might inadvertently reinforce negative stereotypes about disability. By focusing primarily on the difficulties and limitations experienced during the simulation, students might come away with a perception of disability that is primarily deficit-based—seeing disability only as a series of challenges or problems to be solved, rather than as a valid form of human diversity; 4. Emotional and Ethical Concerns Some argue that simulated disability training can lead to emotional discomfort or distress, which, while intended to build empathy, may not always result in constructive learning outcomes. |

| Disabled–Expert-Led Method | |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| 1. Firsthand Perspective A trainer with a disability provides personal, lived experiences, offering participants authentic insight into the challenges, barriers, and triumphs faced by people with disabilities. This real-world perspective often resonates more deeply than theoretical knowledge; 2. Limited Scope of Experience: A disabled trainer may offer deep insights based on their own lived experiences, but those experiences will not represent the full diversity of disabilities. A trainer with a mobility impairment will have a different perspective from someone with a sensory or cognitive disability; 3. Empathy and Connection Hearing directly from someone with a disability helps break down stereotypes and misconceptions. It creates a human connection, fostering empathy; 4. Breaking Stereotypes When a disabled person leads the training, it challenges preconceived notions and stereotypes about disability. It helps shift the narrative from seeing disabilities as limitations to recognizing their capabilities and achievements; 5. Practical and Realistic Solutions Trainers with disabilities often provide practical, actionable advice based on their own experiences. They understand firsthand the most effective accommodations and tools, and their advice is grounded in lived reality; 6. Enhanced Authenticity The authenticity of a disabled trainer’s experience adds credibility to the training. Their personal accounts and challenges make the learning process more engaging; 7. Greater Awareness of Hidden Barriers Disabled trainers are often able to highlight less obvious barriers, such as social exclusion or challenges in communication. Their insights can help participants recognize the subtle ways that environments can be disabling and offer solutions that may not have been considered otherwise. | 1. Perception of Bias Participants may perceive that a disabled trainer is biased or overly focused on their specific challenges, which could reduce the perceived objectivity of the training; 2. Pressure to Represent the Entire Disabled Community: Disabled trainers might feel pressured to speak on behalf of all people with disabilities, which is an unrealistic expectation; 3. Narrow Focus on Disability Issues: A trainer with a disability might, understandably, focus on disability-related issues, potentially leaving out broader diversity and inclusion topics; 4. Risk of Paternalism Some participants may view the disabled trainer in light of their disability rather than their expertise, treating them as “inspiring” for overcoming challenges. This can shift the focus away from the content of the training itself and turn the trainer into a subject of fascination, diminishing the educational value; 5. Overemphasis on Personal Stories While personal stories are powerful and impactful, too much reliance on them might cause the training to become anecdotal rather than research-based. The audience may need a balance between personal experience and objective data; 6. Physical and Logistical Challenges Depending on the nature of the trainer’s disability, there may be logistical issues in delivering the training, especially if it requires travel, certain accommodations, or a specific setup. These challenges could limit the trainer’s ability to offer in-person training; 7. Potential Discomfort for the Trainer: Sharing personal experiences related to disability can be emotionally taxing for the trainer. The trainer may encounter resistance, uncomfortable questions, or even discriminatory attitudes from participants. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonenberg, A.; Linowiecka, B. Teaching Accessible Space in Architectural Education: Comparison of the Effectiveness of Simulated Disability Training and Expert-Led Methods. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030391

Bonenberg A, Linowiecka B. Teaching Accessible Space in Architectural Education: Comparison of the Effectiveness of Simulated Disability Training and Expert-Led Methods. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030391

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonenberg, Agata, and Barbara Linowiecka. 2025. "Teaching Accessible Space in Architectural Education: Comparison of the Effectiveness of Simulated Disability Training and Expert-Led Methods" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030391

APA StyleBonenberg, A., & Linowiecka, B. (2025). Teaching Accessible Space in Architectural Education: Comparison of the Effectiveness of Simulated Disability Training and Expert-Led Methods. Education Sciences, 15(3), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030391