Abstract

High school students face critical psychological challenges during adolescence, including academic pressures and educational decision-making. Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration provides a framework for understanding growth through disintegration and reintegration, with perfectionistic traits acting as intrinsic motivators for self-improvement. This study examined the psychological profiles of 641 Taiwanese high school students: 207 mathematically and scientifically talented students (MSTS), 187 verbally talented students (VTS), and 247 regular students (RS). Using the ME III, refined from the ME II, and the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, our research assessed overexcitabilities (OEs) and perfectionism traits. MSTS and VTS scored significantly higher in Intellectual and Imaginational OEs than RS, with VTS also overperforming in sensual OE. MSTS and VTS showed higher personal standards, while VTS excelled in organization, and RS reported higher parental criticism. Emotional OE correlated with perfectionism, such as concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and parental criticism, while Intellectual OE positively correlated with personal standards and negatively with parental criticism. Intellectual and Emotional OEs jointly predicted personal standards and organization; while Sensual, Intellectual, and Emotional OEs predicted doubts about actions, etc. These findings underscore the importance of tailored educational and counseling strategies to address the unique needs of gifted students, fostering environments that enhance their abilities and overall well-being.

1. Introduction

High school adolescents face critical psychological and personality development challenges as they transition to adulthood, balancing academic competition and future educational decisions. Psychological adaptation is essential for overall well-being. Dabrowski’s (1964) Theory of Positive Disintegration (TPD) suggests that individuals progress through disintegration and reintegration to achieve higher personal development, with perfectionistic traits driving self-improvement.

Early research on perfectionism primarily focused on its detrimental effects, particularly in clinical contexts, where it was linked to procrastination, anxiety, depression, and various health issues such as obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, alcoholism, and colonic ulcers (Fang, 2012; Frost et al., 1990; Jowett et al., 2016). However, contemporary studies recognize that perfectionism can also serve as a driving force for excellence, especially among high achievers (Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, 2014; Petersson et al., 2014; Tan, 2012; Tseng, 2014; Tung, 2008; Y.-T. Yeh, 2000).

This study examines high school students’ psychological traits using the Overexcitability Questionnaire and the Perfectionism Scale, comparing gifted and regular students to provide insights for counseling practices and gifted education strategies.

1.1. Overexcitabilities

Kazimierz Dabrowski defined overexcitabilities (OEs) as stronger than average responsiveness to stimuli, manifested either by psychomotor, sensual, emotional, imaginational, and intellectual excitability, or a combination thereof (as cited in Mendaglio & Tillier, 2006, p. 69). Gifted students frequently display these traits, leading to emotional intensity and potential adaptation difficulties (Piechowski, 1997; Kuo, 2000). However, overcoming internal conflicts fosters personality development, a core tenet of the TPD (Mendaglio, 2012).

Standardized intelligence tests are commonly used to identify giftedness, but they overlook essential personality traits (Piechowski & Cunningham, 1985). Research indicates that gifted individuals exhibit multiple OEs (Wood et al., 2024). Intelligence is influenced by personality and interests (Ackerman & Heggestad, 1997), suggesting that OEs could enhance giftedness identification beyond cognitive measures. Intellectual Overexcitability (TOE) is the most significant OE distinguishing gifted students from their regular peers, as evidenced by multiple studies (Alsaffar, 2023; Bailey, 2011; Y.-P. Chang, 2003; H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009; H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2013; Y.-P. Chang & Kuo, 2019; Hsieh, 2005; Huang, 2005; Lin, 2013; E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2015; Nee, 2013; Piirto & Fraas, 2012; Sousa & Fleith, 2022; Tieso, 2007; Van den Broeck et al., 2014; P.-C. Wu, 2005).

Emotional Overexcitability (EOE) is another key characteristic of gifted students (Bouchet & Falk, 2001; Y.-P. Chang & Kuo, 2019), especially among those gifted in humanities and social sciences (Nee, 2013). Many studies highlight elevated EOE scores alongside TOE scores (Bouchet & Falk, 2001; Miller et al., 1994; De Bondt & Van Petegem, 2015). Imaginational Overexcitability (MOE) is frequently observed in gifted students, particularly in the humanities and creative domains (Nee, 2013). Research also links MOE with creative thinking ability (Huang, 2005; Wei, 2008). Studies have found high MOE scores alongside TOE and EOE scores (Miller et al., 1994; H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009).

Sensual Overexcitability (SOE) is prominent in artistically gifted students, especially those in talent programs (Wei, 2008). English majors exhibited high scores across SOE, TOE, MOE, and EOE (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009). Studies also found SOE paired with TOE or EOE (De Bondt & Van Petegem, 2015; Van den Broeck et al., 2014). Psychomotor Overexcitability (POE), though less emphasized, appears in gifted individuals with strong psychomotor activity, particularly dance-gifted students (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009). Some research associates POE with TOE and EOE (Ackerman & Heggestad, 1997; De Bondt et al., 2019).

Overall, TOE is the most defining OE among gifted students, followed by EOE, particularly among those gifted in humanities, and MOE relates with creativity. These findings also highlight distinct OE profiles among various gifted populations, underscoring the need for tailored educational and counseling strategies to support their specific cognitive and emotional development.

1.2. Perfectionism

According to the Merriam-Webster (2025) Dictionary, perfectionism is “a disposition to regard anything short of perfection as unacceptable,” which carries a negative connotation. Perfectionism is now widely regarded as a multidimensional construct with distinct positive and negative components. Frost et al. (1990) categorized perfectionism into six dimensions: concern over mistakes (CM), personal standards (PS), parental expectations (PE), parental criticism (PC), doubts about actions (DA), and organization (Org). These were later grouped into two broader categories: adaptive (positive) and maladaptive (negative) perfectionism. Personal standards and organization are considered adaptive, as they contribute to motivation and academic success, whereas concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, parental expectations, and parental criticism are classified as maladaptive due to their associations with anxiety and self-doubt (Rice & Taber, 2018; Shen, 2010; Terry-Short et al., 1995).

Positive perfectionism, characterized by high personal standards and organization, is associated with positive academic and performance outcomes. Research indicates that gifted students score significantly higher than regular students in these dimensions (Hsiao & Liang, 2013; Y.-J. Lee, 2005; Locicero & Ashby, 2000; Margot & Rinn, 2016; E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2018; E. Mofield et al., 2016; Preuss & Dubow, 2004; Siegle & Schuler, 2000; Suldo et al., 2008; Tan, 2012; Tseng, 2014; Tung, 2008; Y.-T. Yeh, 2000). These traits enable gifted students to develop strong goal-setting skills, perseverance, and resilience in facing challenges. Additionally, gifted students often demonstrate cognitive flexibility, which leads to a protective factor, allowing them to adopt adaptive coping strategies for stress management and problem-solving (Locicero & Ashby, 2000; Preuss & Dubow, 2004; Suldo et al., 2008). This adaptability mitigates the potential negative effects of perfectionism, reinforcing their learning resilience and overall psychological well-being (E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2018; Wang, 2013).

Parenting styles play a crucial role in shaping perfectionist tendencies in adolescents. Research suggests that parental expectations and criticisms are strongly associated with gender, birth order, and individual personality traits (Basirion et al., 2014; Su, 2005). Some studies indicate that gifted students report lower levels of parental expectations compared to their non-gifted peers (Y.-J. Lee, 2005), while other research finds that regular students tend to score higher in both parental expectations and parental criticism dimensions (Margot & Rinn, 2016; Siegle & Schuler, 2000). Parents often place higher expectations on their eldest children, providing greater academic support to help them succeed. On the other side, as gifted students advance academically, they may experience increased parental pressure, which can shape their perfectionist tendencies (Kornblum & Ainley, 2005). Excessive parental criticism and unrealistic standards contribute to negative perfectionism, increasing stress and emotional distress (Margot & Rinn, 2016). Therefore, maintaining balanced parental expectations is essential in fostering adaptive perfectionism while minimizing psychological distress in both gifted and regular students.

Concern over mistakes and doubts about actions are key dimensions of perfectionism that significantly impact students’ psychological well-being. Although these traits are often associated with maladaptive perfectionism, they can also reflect a careful and strategic approach to decision-making when maintained at moderate levels (Rice & Taber, 2018; Shen, 2010; Terry-Short et al., 1995). However, excessive concern over mistakes and doubts about actions can lead to heightened anxiety, reduced self-efficacy, and fear of failure, particularly among neurotic perfectionists (Affrunti & Woodruff-Borden, 2014; Chen & Kuo, 2013; Fang, 2012; Gnilka et al., 2012; Hibbard & Walton, 2014; Liu, 2014; E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2015; E. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2019; E. Mofield et al., 2016; Mok, 2013; Petersson et al., 2014; Tsai, 2010; Tseng, 2014; Wang, 2013; Y.-T. Yeh, 2000; C.-H. Yeh, 2004). Gifted students tend to score higher in concern over mistakes compared to their regular peers, indicating heightened self-awareness and self-criticism (E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2018; Wang, 2013). However, well-adjusted gifted students often exhibit greater adaptability in managing mistakes, which mitigates the negative effects of perfectionism and enhances their learning resilience (Locicero & Ashby, 2000). In contrast, students with excessive concern over mistakes and doubts about actions may struggle with academic pressure, experience frustration, and develop avoidance behaviors. Understanding the balance between productive self-reflection and negative perfectionism is essential for educators and parents to support students’ emotional well-being and academic success.

1.3. Correlations Between OEs and Perfectionism

Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration emphasizes emotional and personality development, emphasizing self-directed personal factors, alongside physiological and environmental influences. The pursuit of perfection or self-actualization arises from intrinsic motivation, establishing a strong connection between overexcitabilities (OEs) and perfectionism.

Intellectual Overexcitability (TOE) plays a crucial role in perfectionism, as evidenced by multiple studies. Razak et al. (2021) found a significant correlation between OE and perfectionism traits (r = 0.693, p < 0.0005), highlighting TOE as a key driver of perfectionist tendencies, unrealistic expectations, and social-intellectual asynchrony. Similarly, White (2007) reported a strong association between TOE and perfectionism (r = 0.407, p = 0.000), reinforcing its role in striving for high personal standards and self-improvement. E. L. Mofield and Parker Peters (2015) further identified significant correlations between TOE and multiple perfectionism dimensions, including personal standards (PS; r = 0.29), doubts about actions (DA; r = 0.19), and concern over mistakes (CM; r = 0.18). In a more recent study, Liao and Kuo (2023) found TOE to be significantly correlated with PS (r = 0.533), organization (O; r = 0.433), and DA (r = 0.399), further supporting the link between intellectual intensity and perfectionist traits.

Emotional Overexcitability (EOE) has been widely linked to both adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. E. L. Mofield and Parker Peters (2015) identified significant correlations between EOE and multiple perfectionism dimensions, including personal standards (PS; r = 0.32), organization (O; r = 0.28), concern over mistakes (CM; r = 0.27), and doubts about actions (DA; r = 0.26). Similarly, White (2007) reported a strong association between EOE and perfectionism (r = 0.647, p = 0.000), reinforcing its role in perfectionist tendencies. However, while EOE may contribute to high personal standards, it has also been associated with psychological maladjustment. Studies indicate that EOE negatively predicts personal and social adjustment, while contributing to emotional distress (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2013; Y.-P. Chang & Kuo, 2019). Perrone-McGovern et al. (2015) found that EOE significantly predicted emotional regulation difficulties (β = −0.21, p < 0.001), with individuals high in EOE exhibiting lower emotional regulation and increased negative perfectionism. In contrast, positive perfectionism was linked to better emotional regulation (β = 0.77, p < 0.001). Y.-P. Chang and Kuo (2019) further associated EOE with three maladjustment dimensions: personal adaptation (r = 0.50, p < 0.01), social adaptation (r = 0.41, p < 0.01), and emotional distress (r = 0.54, p < 0.01). More recently, Liao and Kuo (2023) found EOE to be significantly correlated with doubts about actions (r = 0.495), concern over mistakes (r = 0.575), and parental criticism (r = 0.417), reinforcing its connection to negative perfectionism. High EOE individuals often experience heightened anxiety and emotional tension, though those who employ positive emotional regulation strategies may achieve greater psychological well-being.

E. L. Mofield and Parker Peters (2015) identified correlations between MOE and DA (r = 0.27) as well as PC (r = 0.26), suggesting a link between MOE and self-doubt. Thomson and Jaque (2016) observed that MOE, along with EOE, may exacerbate shyness, anxiety, and depression. Additionally, Alsaffar (2023) found that MOE negatively affected positive emotional regulation. Thomson and Jaque (2023) also reported a positive association between MOE and maladaptive daydreaming. Despite these challenges, MOE has been found to contribute to psychological adjustment in some contexts (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2013). Overall, MOE appears to play a complex role in perfectionism, influencing both adaptive and maladaptive traits.

Although less extensively studied, SOE has been linked to perfectionism. White (2007) found a significant correlation between SOE and perfectionism (r = 0.343, p = 0.001). This suggests that heightened sensory awareness may contribute to a preference for order and high personal standards, aligning with certain dimensions of perfectionism. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this relationship require further exploration.

Overall, research suggests that different OEs contribute uniquely to perfectionism. High TOE and high EOE tend to predict positive perfectionism, characterized by striving for excellence and adaptive emotional regulation. In contrast, high MOE, EOE, and POE are more closely associated with negative perfectionism, leading to heightened self-criticism and emotional maladjustment (E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2015). Bailey (2011) noted that most adolescents experience the “unilevel disintegration stage” in Dabrowski’s theory, a critical transition toward higher personality levels. This developmental phase is often marked by inner conflict and dissatisfaction, driving individuals toward self-improvement. From Dabrowski’s perspective, perfectionism itself can be viewed as an expression of OEs, where feelings of guilt, anxiety, and personal dissatisfaction fuel the pursuit of self-perfection and greater personal growth.

1.4. Research Purposes

This study aims to investigate overexcitabilities (OEs) and perfectionism in gifted high school students by comparing the characteristics of gifted and regular students, and by examining the relationships among these psychological traits. The objectives are as follows:

- Revise the ME Scale II, reducing it from ten subscales to five subscales directly corresponding to the five OE items in Dabrowski’s theory. Test the reliability and validity of the new scale.

- Compare the levels of overexcitabilities (OEs) and perfectionism among different types of gifted and regular students.

- Investigate the correlations between overexcitabilities (OE) and perfectionism.

- Analyze the predictive power of overexcitabilities (OE) on perfectionism.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 10th-grade students, aged 16 to 17, from 12 high schools across northern, central, southern, and eastern Taiwan. The sample included 207 mathematically and scientifically talented students (MSTS) (127 males, 80 females), 187 verbally talented students (VTS) (78 males, 109 females), and 247 regular students (RS) (102 males, 145 females), yielding a total of 641 valid cases (Table 1). In Taiwan, mathematically gifted programs typically enroll more males, while verbally talented programs have a higher proportion of females. Gender distribution in regular classes was based on returned questionnaires. Due to this unequal gender distribution, gender differences were not analyzed.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participants.

MSTS and VTS were identified through the gifted identification process administered by the Identification and Placement Committee Board for Students with Special Needs. To qualify as gifted in academic domains, students were required to meet at least one of the following criteria:

- Specific academic aptitude achievement test scores that are two standard deviations above the mean or in the 97th percentile rank or above, accompanied by recommendations from professionals, teachers, or parents, and supported by documents detailing learning traits and demonstrations of abilities.

- Receipt of one of the first three prizes in an international or national academic contest or exhibition.

- Participation in an academic seminar held by a research institute with excellent performance, accompanied by a recommendation from the host institute.

- Submission of research reports published in academic journals, supported by recommendations from professionals or teachers.

2.2. Research Procedure

The study was conducted in the latter half of 2016. Initially, school administrators were contacted to assess their willingness to participate. For schools that agreed, questionnaires were distributed and later collected by administrators or homeroom teachers before being returned to the research team. The research process followed these steps:

- August–September 2020: contacted designated teachers at participating schools via phone; confirmed the required number of questionnaires and arranged for printing; mailed questionnaires along with relevant documents;

- October–December 2020: Administered the survey according to each school’s schedule; collected, coded, and entered questionnaire data.

- January 2021: Conducted data analysis; drafted the research report.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MP)

The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale was developed by Frost, Marten, and Lahart in 1990, using a Likert-type 5-point scale. Higher scores indicate stronger perfectionism traits. Frost et al. classified perfectionism into six psychological dimensions:

- Concern over Mistakes (CM): Reflects a tendency to view mistakes as failures and to believe that failure results in a loss of respect from others.

- Personal Standards (PS): Reflects a tendency to set high standards for oneself and to overemphasize their importance in self-evaluation.

- Parental Expectations (PE): Reflects a belief that parents set excessively high standards.

- Parental Criticism (PC): Reflects a tendency to feel overly criticized by parents.

- Doubts about Actions (DA): Reflects a tendency to doubt one’s ability to complete tasks.

- Organization (Org.): Measures the belief that everything should be well-organized and orderly.

The scale was revised and translated into Chinese by Lu Jun-Hong et al. in 1999. The revised Chinese version contains 35 items and retains the six subscales. The internal consistency reliability for the overall scale is Cronbach’s α = 0.91. The subscale reliabilities, ranked from highest to lowest, are organization (Org.) = 0.89, concern over mistakes (CM) = 0.85, personal standards (PS) = 0.81, parental criticism (PC) = 0.76, doubts about actions (DA) = 0.74, and parental expectations (PE) = 0.70. The PS and Org. subscales align with “positive perfectionism,” while the CM, PE, PC, and DA subscales correspond to “negative perfectionism” (Fang, 2012; Frost et al., 1993). Example items from the MP scale include: “No matter what I do, I demand that it be done perfectly, without any flaws,” “When something is not done perfectly, I redo it until I am satisfied,” and “I am deeply affected by others’ criticisms.”

2.3.2. The ME Scale III

This study employs the third edition of the “ME” Scale, which was originally developed as the “ME” Scale II by H.-J. Chang (2011) to assess overexcitability (OE) traits. The revised scale was refined through factor analysis, reducing the number of items from 62 to 40 while maintaining robust psychometric properties. The ME Scale III utilizes a seven-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger OE traits.

The scale comprises five subscales, each capturing a distinct dimension of overexcitability: Psychomotor OE (POE), Sensual OE (SOE), Intellectual OE (TOE), Imaginational OE (MOE), and Emotional OE (EOE), with each subscale containing eight items. To evaluate the reliability of the ME Scale III, internal consistency was examined by using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. The results indicate strong to acceptable internal consistency across the subscales: MOE = 0.880, POE = 0.808, TOE = 0.789, EOE = 0.734, and SOE = 0.724. The overall scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.880, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, demonstrating high internal consistency (Drost, 2011).

The validity of the scale was assessed through factor analysis. Before conducting factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were applied to determine the appropriateness of the data. The KMO value for the ME Scale III was 0.887, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.60 (M.-L. Wu & Tu, 2005), indicating a substantial presence of common factors among the variables and confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The total variance explained by the extracted factors was 44.856%, further supporting the construct validity. Additionally, all factor loadings exceeded 0.50 (Table 2), confirming strong convergent validity. In conclusion, the ME Scale III demonstrates good psychometric properties, with high internal consistency and construct validity. The scale provides a reliable and valid tool for assessing overexcitability traits across multiple dimensions.

Table 2.

Factor Analysis of Items on the ME Scale III.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

After the completed assessments were collected, data analysis was conducted using SPSS/22.0. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were all examined. One-way ANOVA and t-tests were employed to test the differences across groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the relationships between variables, and multiple stepwise regression analysis was performed to determine the predictive power of OE traits on perfectionism.

3. Results

The research team first revised the ME Scale III, confirming its reliability and validity for this study. Subsequently, we compared the performance of gifted and regular students on the OE and MP scales, explored the relationships among the tested traits, and tested the predictive power of OE on MP.

3.1. Differences in OEs Among Gifted Students and Regular Students

The differences among mathematically and scientifically talented students (MSTS), verbally talented students (VTS), and regular students (RS) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean scores and standard deviation of OEs among different students.

MSTS and VTS demonstrated significantly higher TOE (F = 48.35, p < 0.0001) and MOE (F = 9.17, p < 0.0001) scores than RS, with VTS also exhibiting higher SOE scores (F = 9.05, p < 0.0001). No significant differences were observed in POE or EOE.

3.2. Differences in Perfectionism Among Gifted Students and Regular Students

The differences in perfectionism among mathematically and scientifically talented students (MSTS), verbally talented students (VTS), and regular students (RS) are shown in Table 4. MSTS and VTS reported higher personal standards (PS) (F = 19.50, p < 0.0001), with VTS showing greater organization (Org) (F = 4.65, p < 0.05) scores, while RS had higher parental criticism (PC) (F = 22.03, p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean scores and standard deviations for perfectionism among different students.

3.3. Correlations Among OEs and Perfectionism

Table 5 shows the correlations among subscales. Moderate to low correlations were found among OE and MP subscales. EOE showed higher correlations with perfectionism subscales such as concern over mistakes (r = 0.452 **), doubts about actions (r = 0.462 **), and parental criticism (r = 0.340 **), and parental expectation (r = 0.252 **). MOE exhibited low correlations with personal standards (r = 0.245 **), organization (r = 0.106 **), doubts about actions (r = 0.149 **), and parental expectation (r = 0.105 **). POE showed low correlations with personal standards (r = 0.210 **), organization (r = 0.131 **), concern over mistakes (r = 0.138 **), doubts about actions (r = 0.187 **), and parental expectation (r = 0.158 **). SOE positively correlated with organization (r = 0.317 **), personal standard(r = 0.249 **), doubts about actions (r = 0.256 **), and concern over mistakes(r = 0.117 **). TOE positively correlated with personal standards (r = 0.524 **), organization (r = 0.349 **), and doubts about actions (r = 0.240 **), and negatively correlated with parental criticism (r = −0.134 **).

Table 5.

Correlations among scores for OE and MP (N = 641).

3.4. Predictive Validity of OEs on Perfectionism

Regression analysis was conducted to explore the predictive power of OEs on perfectionism, as summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

The predictions of OEs on perfectionism: results of multiple regression analyses.

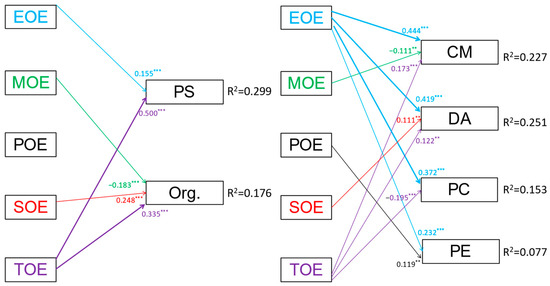

TOE and EOE jointly predicted personal standards in perfectionism with statistical significance (R2 = 0.299) and negatively predicted doubts about actions (R2 = 0.153), while EOE, TOE, and MOE collectively predicted concern over mistakes (R2 = 0.227). EOE, TOE, and SOE collectively predicted doubts about actions (R2 = 0.251).

Figure 1 illustrates the predictive relationships between OEs and different dimensions of perfectionism. The results indicate that TOE is the strongest predictor of personal standards (PS) and organization (Org.), both of which are considered aspects of positive perfectionism. In contrast, EOE is the most significant predictor of concern over mistakes (CM) and doubts about actions (DA), which are key indicators of negative perfectionism. Additionally, SOE contributes to organization, while POE does not show a significant relationship with positive perfectionism but is associated with parental expectations (PE). These findings highlight the complex interplay between overexcitabilities and perfectionistic tendencies.

Figure 1.

Prediction of Perfectionism through OEs. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Note: EOE = Emotional OE, MOE = Imaginational OE, POE = Psychomotor OE, SOE = Sensual OE, TOE = Intellectual OE, PS = personal standard, Org. = organization, CM = concern over mistakes, DA = doubts about actions, PC = parental criticism, PE = parental expectation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in OEs Among Gifted Students and Regular Students

This study revealed that gifted students exhibit higher levels of overexcitabilities (OEs) compared to regular students, particularly in MOE, TOE, and SOE.

Mathematically and scientifically talented students (MSTS) and verbally talented students (VTS) exhibited significantly higher TOE scores compared to regular students (RS), reinforcing the notion that intellectual intensity is a defining characteristic of giftedness (Alsaffar, 2023; Bailey, 2011; H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009; H.-J. Chang, 2001; Y.-P. Chang, 2003; Lin, 2013; E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2015; Sousa & Fleith, 2022; Tieso, 2007; Van den Broeck et al., 2014; P.-C. Wu, 2005). This finding supports Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration (TPD), which posits that individuals with heightened intellectual sensitivity tend to engage in deeper and more complex cognitive processing, ultimately fostering advanced personal and academic development.

The superior creativity and imagination of gifted students, compared to regular students, aligns with findings from prior studies in Taiwan (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009; Huang, 2005; Lin, 2013). Additionally, gifted students demonstrated elevated SOE levels, especially those gifted in arts and humanities (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2009; Huang, 2005; Lin, 2013; Nee, 2013; Van den Broeck et al., 2014; Wei, 2008). A significant difference in SOE was also observed between MSTS and VTS, with the latter excelling in humanities and social sciences. Their heightened sensitivity facilitates an appreciation for humanities and arts, while their imagination supports artistic creation, making SOE particularly valuable for language-gifted students. This suggests that verbally talented students may possess heightened aesthetic sensitivity, allowing them to engage more deeply with literature, music, and other forms of artistic expression. Such findings have significant implications for educational practices, emphasizing the need to integrate creative and sensory-stimulating activities into gifted education programs, particularly for verbally talented students.

4.2. Differences in Perfectionism Among Gifted Students and Regular Students

This study found that MSTS and VTS reported higher personal standards than RS, while VTS also exhibited higher organization than RS. Personal standards and organization are widely recognized as traits associated with positive perfectionism; the pursuit of perfection serves as a driving force for progress, and outstanding individuals often demonstrate considerable degrees of perfectionism. For example, gifted students outperform regular students in PS and Org. (Y.-J. Lee, 2005; Locicero & Ashby, 2000; E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2018). Our results align closely with those from prior studies.

Conversely, RS reported higher parental criticism (PC) than MSTS and VTS. Excessive concern over mistakes, parental criticism, and doubts about actions are commonly linked to negative perfectionism (Frost & Henderson, 1991), under the influence of high parental expectations, may experience greater anxiety about potential parental criticism related to academic performance. Jeong and Ryan (2022) highlighted that societal and parental pressures toward perfectionism can foster stress and frustration in children, potentially undermining their motivation to learn. Interestingly, MSTS and VTS did not report high levels of parental criticism. This may be attributed to their status as high achievers, particularly in academic performance, which likely reduced parental criticism.

4.3. Correlations Among OEs and Perfectionism

This study found that EOE exhibited higher correlations with perfectionism subscales, including concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and parental criticism. EOE is closely linked to social adaptation and emotional disorders (H.-J. Chang & Kuo, 2013; Y.-P. Chang & Kuo, 2019). Thomson and Jaque (2016) noted that EOE could exacerbate negative emotions such as shyness, anxiety, and depression, making high EOE individuals more prone to psychological maladjustment. Perrone-McGovern et al. (2015) reported significant correlations between EOE and perfectionism, with high EOE individuals showing lower emotional regulation scores, resulting in negative perfectionism. Conversely, positive perfectionists demonstrated better emotional regulation. Our findings align with prior literature on these correlations.

Additionally, this study found that SOE positively correlated with organization, while TOE positively correlated with personal standards and organization and negatively correlated with parental criticism. White (2007) identified a correlation between perfectionism and SOE, which our study confirms, with the strongest correlation being with organization. TOE, a hallmark trait of gifted students, supports high personal standards and organization, which are critical for high achievement. These results are consistent with earlier findings (E. L. Mofield & Parker Peters, 2015).

While E. L. Mofield and Parker Peters (2015) identified significant correlations between MOE and doubts about actions and parental criticism, this study found lower correlations among MOE and personal standards, organization, and doubts about actions.

POE, based on our research, exhibited low correlations with personal standards, organization, concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and parental expectations. This suggests that POE is not solely linked to negative perfectionism but also has associations with positive perfectionism. According to Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration, students with strong POE may experience more positive personal development if they also demonstrate a balanced presence of EOE and TOE. The interaction between these OEs can help regulate impulsivity and high energy while enhancing emotional awareness and intellectual reflection. This balance fosters more adaptive and constructive growth, allowing individuals to channel their intensity in a productive and meaningful way.

4.4. Predictive Validity of Overexcitabilities on Perfectionism

This study provides further empirical evidence regarding the predictive relationship between overexcitabilities and perfectionism, supporting previous research that links heightened sensitivity and cognitive complexity to perfectionistic tendencies. As illustrated in Figure 1, different OEs exhibit distinct predictive patterns for positive and negative perfectionism.

TOE emerged as the strongest positive predictor of personal standards (PS), a core component of positive perfectionism. Regression analysis showed that TOE had the highest predictive power for PS (β = 0.500, p < 0.001), indicating that students with heightened intellectual intensity tend to establish and maintain exceptionally high personal standards. This finding aligns with Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration, which suggests that intellectually gifted individuals continuously strive for self-fulfillment, often through rigorous self-imposed goals. Furthermore, EOE also significantly predicted PS, although to a lesser extent than TOE, highlighting the role of emotional depth in reinforcing high personal aspirations. Additionally, organization (Org.), another indicator of positive perfectionism, was significantly predicted by TOE (β = 0.335, p < 0.001) and SOE (β = 0.248, p < 0.001). This suggests that students with intellectual and aesthetic sensitivities are more likely to value structure and order in their academic and personal lives. The influence of SOE on organization underscores the importance of sensory experiences in shaping disciplined and meticulous behaviors among students, particularly those engaged in artistic and literary pursuits.

Conversely, EOE was identified as the strongest predictor of concern over mistakes (CM) (β = 0.444, p < 0.001) and doubts about actions (DA) (β = 0.419, p < 0.001), both of which are key dimensions of negative perfectionism. These findings suggest that students with high emotional sensitivity are more prone to self-doubt and anxiety regarding their performance. The heightened emotional responsiveness characteristic of EOE may amplify the fear of failure and excessive self-criticism, ultimately fostering maladaptive perfectionistic behaviors (Alsaffar, 2023; Y.-P. Chang & Kuo, 2019; Thomson & Jaque, 2016, 2023).

Similarly, parental criticism (PC) was significantly predicted by EOE (β = 0.372, p < 0.001), indicating that students with high emotional sensitivity are more likely to perceive external pressure from parental expectations and judgments. TOE, on the other hand, negatively predicted PC (β = −0.195, p < 0.001), suggesting that intellectually driven students may be more resilient to external criticism. This finding aligns with previous research showing that intellectually gifted students often develop self-referential motivation rather than relying on external validation for their achievements (Razak et al., 2021).

Interestingly, POE was the only OE that did not significantly predict positive perfectionism, reinforcing prior studies indicating that physical hyperactivity is not directly linked to goal-setting behaviors or structured achievement striving. However, POE did contribute to negative perfectionism, particularly to parental expectations (PE), where students with high POE may experience increased pressure from their parents due to their high-energy, restless nature.

4.5. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study focused exclusively on 10th-grade students (ages 16–17) in Taiwan, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to students of different age groups or those from other cultural and educational contexts. Additionally, gender distribution in the sample was uneven, with a higher proportion of male students in the mathematically and scientifically talented programs and more female students in the verbally talented programs. This imbalance restricted the ability to analyze gender differences in overexcitabilities and perfectionism traits. Regarding measurement tools, the study employed the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) and the ME Scale III, both of which demonstrate strong reliability and validity. However, these instruments may not comprehensively capture all psychological characteristics relevant to gifted students. Future research could incorporate alternative OE-related scales and qualitative methodologies to gain a more in-depth understanding of these traits. Another limitation concerns data collection, as self-reported questionnaires were the primary source of information. While self-reports offer valuable perspectives on students’ subjective experiences, they are susceptible to social desirability bias, potentially leading to the overestimation or underestimation of certain psychological traits. Future studies should incorporate multiple assessment methods, such as teacher evaluations, parental reports, and physiological or behavioral measures, to enhance data accuracy and comprehensiveness.

By addressing these research directions, future studies can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the psychological characteristics of gifted students, ultimately informing more effective educational policies and support systems.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

This study highlights significant differences in overexcitabilities (OEs) and perfectionism traits among gifted and regular high school students. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring educational and counseling approaches to meet the unique needs of students in different programs. To support the psychological and educational development of gifted students, the following recommendations are proposed:

Counseling Support: Schools should provide tailored counseling services to help gifted students manage their heightened sensitivities and perfectionistic tendencies. These services can promote their overall well-being and enhance their academic success.

Parent Education: Educating parents about the unique traits and needs of gifted students can foster a supportive home environment that nurtures their development without imposing undue pressure. Parental awareness can mitigate the risk of negative perfectionism.

Teacher Training: Teachers should receive specialized training to recognize and address the specific needs of gifted students. By understanding and utilizing their overexcitabilities as strengths, educators can help these students thrive both academically and emotionally.

Further Research: Additional studies should investigate the long-term effects of overexcitability and perfectionism on the academic and personal lives of gifted students. Understanding the dual aspects of perfectionism—both positive and negative—can aid educators and counselors in enhancing its beneficial impacts while mitigating its adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.K.; methodology, C.-C.K. and C.-H.C.; software, C.-C.C.; validation, C.-C.K.; formal analysis, C.-C.L., C.-C.K. and C.-H.C.; investigation, C.-C.L., C.-C.K. and C.-H.C.; resources, C.-C.L. and C.-C.K.; data curation, C.-H.C., C.-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-C.L. and C.-H.C.; writing—review and editing, C.-C.K. and C.-C.C.; visualization, C.-C.C.; supervision, C.-C.K. Writing—review & editing, C.-C.K. and C.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the survey was conducted by school teachers, and students were not required to offer individual identification.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We have ample research-related data; however, these data are not publicly available on any website or online repository. If anyone is interested in accessing the data, we would be happy to provide them upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ackerman, P. L., & Heggestad, E. D. (1997). Intelligence, personality, and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin, 121(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affrunti, N. W., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2014). Perfectionism in pediatric anxiety and depressive disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaffar, K. F. (2023). Overexcitability and its impact on psychosomatic disorders and the role of “Cognitive emotion regulation” as a mediating variable. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C. L. (2011). An examination of the relationships between ego development, Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration, and the behavioral characteristics of gifted adolescents. Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(3), 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basirion, Z., Abd Majid, R., & Jelas, Z. M. (2014). Big five personality factors, perceived parenting styles, and perfectionism among academically gifted students. Asian Social Science, 10(4), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, N., & Falk, R. F. (2001). The relationship among giftedness, gender, and overexcitability. Gifted Child Quarterly, 45(4), 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J. (2001). A research on the overexcitability traits of gifted and talented students in Taiwan, ROC [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-J. (2011). The study of over-excitabilities: Predicting learning performance, creativity, and psychological adjustment in gifted and regular students [Ph.D. Dissertation, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-J., & Kuo, C.-C. (2009). Overexcitabilities of gifted and talented students and its related research in Taiwan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Gifted and Talented Education, 1(1), 41–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-J., & Kuo, C.-C. (2013). Overexcitabilities: Empirical studies and application. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-P. (2003). The emotional development levels and adjustment of math-science talented students in senior high schools [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-P., & Kuo, C.-C. (2019). The correlations among emotional development, over-excitabilities, and personal maladjustment. Archives of Psychology, 3(5), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C., & Kuo, C.-C. (2013). A study on the perfectionism and achievements among gifted students with dance talents and regular students. Forum of Gifted Education, 11, 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Little Brown. [Google Scholar]

- De Bondt, N., De Maeyer, S., Donche, V., & Van Petegem, P. (2019). A rationale for including overexcitability in talent research beyond the FFM-personality dimensions. High Ability Studies, 30(1–2), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bondt, N., & Van Petegem, P. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the Overexcitability Questionnaire-Two applying Bayesian structural equation modeling (BSEM) and multiple-group BSEM-based alignment with approximate measurement invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, E. A. (2011). Validity and reliability in social science research. Education Research and Perspectives, 38(1), 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.-W. (2012). The relations among perfectionism, learning problem, and positive and negative affect: The mediating effect of rumination. Bulletin of Educational Psychology, 43(4), 735–762. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., & Henderson, K. J. (1991). Perfectionism and reactions to athletic competition. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(4), 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, C., Lahart, C. M., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimension of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. Available online: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF01172967 (accessed on 16 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gnilka, P. B., Ashby, J. S., & Noble, C. M. (2012). Multidimensional perfectionism and anxiety: Differences among individuals with perfectionism and tests of a coping-mediation model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(4), 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, D. R., & Walton, G. E. (2014). Exploring the development of perfectionism: The influence of parenting style and gender. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(2), 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W.-C., & Liang, C.-H. (2013). Every “perfectionist” has a silver lining!? Psychological review on perfectionism. Gifted Education, 126, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-C. (2005). A study on the overexcited traits and social affective adaptation of junior high school music gifted class students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.-H. (2005). The study of overexcitabilities and creativity of junior high school gifted and talented students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S. S. Y., & Ryan, C. (2022). A critical review of child perfectionism as it relates to music pedagogy. Psychology of Music, 50(4), 1312–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, G. E., Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Curran, T. (2016). Perfectionism, burnout, and engagement in youth sport: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 24, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblum, M., & Ainley, M. (2005). Perfectionism and the gifted: A study of an Australian school sample. International Education Journal, 6(2), 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.-C. (2000). Special adaptation problems and counseling for gifted students. Gifted Education Quarterly, 75, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-J. (2005). The study of depression tendency and related factors of the gifted and talented students in senior high school [Master’s Thesis, National Changhua University of Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.-C., & Kuo, C.-C. (2023). The study of overexcitability, perfectionism, and learning adaptation of art-talented students. Research in Arts Education, 45, 71–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Z. (2013). The study of empathy, overexcitability profiles, and peer relationships on gifted students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-T. (2014). The relationships among perfectionism, academic frustration tolerance, and interpersonal frustration tolerance of musically talented students in the junior high school [Master’s Thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Locicero, K. A., & Ashby, J. S. (2000). Multidimensional perfectionism in middle school age gifted students: A comparison to peers from the general cohort. Roeper Review, 22(3), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margot, K. C., & Rinn, A. N. (2016). Perfectionism in gifted adolescents: A replication and extension. Journal of Advanced Academics, 27(3), 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaglio, S. (2012). Overexcitabilities and giftedness research: A call for a paradigm shift. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(3), 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaglio, S., & Tillier, W. (2006). Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration and giftedness: Overexcitability research findings. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 30(1), 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. (2025). Perfectionism. Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/perfectionism (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Miller, N. B., Silverman, L. K., & Falk, R. F. (1994). Emotional development, intellectual ability, and gender. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 18(1), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofield, E., & Parker Peters, M. (2019). Understanding underachievement: Mindset, perfectionism, and achievement attitudes among gifted students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(2), 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofield, E., Parker Peters, M., & Chakraborti-Ghosh, S. (2016). Perfectionism, coping, and underachievement in gifted adolescents: Avoidance vs. approach orientations. Education Sciences, 6(3), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofield, E. L., & Parker Peters, M. (2015). The relationship between perfectionism and overexcitabilities in gifted adolescents. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofield, E. L., & Parker Peters, M. (2018). Mindset misconception? Comparing mindsets, perfectionism, and attitudes of achievement in gifted, advanced, and typical students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62(4), 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.-J. (2013). A study of perfectionism and self-regulation: Study based on high school students in Taipei [Master’s Thesis, Tamkang University]. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, H.-H. (2013). A comparative study of overexcitabilities and autism spectrum conditions among regular and different kinds of gifted and talented senior high school students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone-McGovern, K. M., Simon-Dack, S. L., Beduna, K. N., Williams, C. C., & Esche, A. M. (2015). Emotions, cognitions, and well-being: The role of perfectionism, emotional overexcitability, and emotion regulation. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 38(4), 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, S., Perseius, K., & Johnsson, P. (2014). Perfectionism and sense of coherence among patients with eating disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 68(6), 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowski, M. M. (1997). Emotional giftedness: The measure of intrapersonal intelligence. In N. Colangelo, & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (pp. 366–381). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Piechowski, M. M., & Cunningham, K. (1985). Patterns of overexcitability in a group of artists. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 19(3), 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piirto, J., & Fraas, J. (2012). A mixed-methods comparison of vocational and identified-gifted high school students on the overexcitability questionnaire. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(1), 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. J., & Dubow, E. F. (2004). A comparison between intellectually gifted and typical children in their coping responses to a school and a peer stressor. Roeper Review, 26(2), 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, A. Z. A., Bakar, A. Y. A., Surat, S., & Majid, R. A. (2021). Perfectionism and overexcitability: Uniqueness or lack of socioemotional development of gifted and talented students? Journal of Legal Studies Education, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, K. G., & Taber, Z. B. (2018). Perfectionism. In Handbook of giftedness in children (pp. 227–254). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.-L. (2010). The correlative study of two-dimensional perfectionism, depression subtypes and positive affect in adolescents: Subjective achievement stress and coping strategies as mediators or moderator [Master’s Thesis, National Chiao Tung University]. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle, D., & Schuler, P. A. (2000). Perfectionism differences in gifted middle school students. Roeper Review, 23(1), 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R. A. R. D., & Fleith, D. D. S. (2022). Emotional development of gifted students: Comparative study about overexcitabilities. Psico-USF, 26, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-Y. (2005). A study on the relationship among parent-child relationship, perfectionism, self-esteem and depressive tendency of adolescents [Master’s Thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, S. M., Shaunessy, E., & Hardesty, R. (2008). Relationships among stress, coping, and mental health in high-achieving high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 45(4), 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y. H. (2012). A study of perfectionism and coping strategies among the gifted students in a secondary school [Master’s Thesis, National Chi Nan University]. [Google Scholar]

- Terry-Short, L. A., Owens, R. G., Slade, P. D., & Dewey, M. E. (1995). Positive and negative perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(5), 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P., & Jaque, S. V. (2016). Overexcitability: A psychological comparison between dancers, opera singers, and athletes. Roeper Review, 38, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P., & Jaque, V. (2023). Maladaptive daydreaming, overexcitability, and emotion regulation. Roeper Review, 45(3), 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieso, C. L. (2007). Patterns of overexcitabilities in identified gifted students and their parents: A hierarchical model. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(1), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-Y. (2010). A comparative study on parenting styles and self-efficacy of the gifted in junior high school with different types of perfectionism. Journal of Gifted Education, 10(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.-C. (2014). A study on the relationships among perfectionism, self-esteem, and resilience of high school students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, L.-H. (2008). Research on the relationship between perfectionism and self-esteem, achievement motivation, irrational beliefs, and physical and mental adaptation. Kaohsiung Medical University Journal of General Education, 3, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, W., Hofmans, J., Cooremans, S., & Staels, E. (2014). Factorial validity and measurement invariance across intelligence levels and gender of the Overexcitabilities Questionnaire-II (OEQ-II). Psychological Assessment, 26, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-M. (2013). A study of perfectionism and depression tendency of the math/science indigenous gifted students and ordinary students in senior high school [Master’s Thesis, National Changhua University of Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.-Y. (2008). The relationship between over-excitabilities and creativity of elementary school art-talented-class students [Master’s Thesis, University of Taipei]. [Google Scholar]

- White, S. (2007). The link between perfectionism and overexcitabilities. Gifted and Talented International, 22(1), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, V. R., Bouchard, L., De Wit, E., Martinson, S. P., & Van Petegem, P. (2024). Prevalence of emotional, intellectual, imaginational, psychomotor, and sensual overexcitabilities in highly and profoundly gifted children and adolescents: A mixed-methods study of development and developmental potential. Education Sciences, 14(8), 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-L., & Tu, C.-T. (2005). SPSS & the application and analysis of statistics. Wu-Nan Book Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.-C. (2005). The comparative investigation of Kaohsiung gifted elementary students and general elementary school students’ over-excitability and life adjustment [Master’s Thesis, National Pingting University]. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, C.-H. (2004). Relationship among perfectionism, explanatory style, and depression of senior high school students: A study of six senior high schools in Taichung [Master’s Thesis, National Taichung University of Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Y.-T. (2000). Relationship between the three of parental rearing style, perfectionism, and physical and mental health in high school students [Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).