Empowering Teacher Professionalism Through Personalized Continuing Professional Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using a Multidimensional Approach to Self-Assessment and Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What kind of continuing professional learning (CPL) frameworks exist to support in-service teachers’ professionalism?

- According to the six aspects of Avidov-Ungar’s (2024, pp. 166–167) Multidimensional Model, what are the components that exist in in-service teachers’ CPL frameworks?

- What challenges do in-service teachers encounter when implementing CPL frameworks across different career stages (early, mid and late)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Planning the Review

- Research Objectives—The primary objectives guiding this review were to: (1) examine the practical frameworks within PCPL that contribute to teacher professionalism (RQ1); (2) explore how these frameworks integrate multidimensional aspects of professional competencies—such as systematic knowledge, lifelong learning, and ethical standards—and job-related components such as means of action, collaborative networks, and role constraints to guide teachers’ CPL (RQ2); and (3) identify challenges teachers face when implementing practical frameworks in CPL, with a focus on how these frameworks can be adapted to support continuing learning and enhance effectiveness across different career stages (RQ3).

- Search Strategy—The Scopus database (https://www.scopus.com/) was selected as the primary source due to its extensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature across multiple disciplines. A structured search was conducted using keywords carefully designed to capture the full scope of PCPL frameworks, teacher professionalism, multidimensional competencies, and implementation challenges within education contexts.

- 3.

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria—The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to this review helped refine the selection process and ensured a focus on relevant, high-quality studies.

- Inclusion Criteria: Empirical, peer-reviewed articles focused on PCPL frameworks that promote teacher professionalism, with attention to practical applications, professional competencies, and adaptability across career stages.

- Exclusion Criteria: Studies that were non-empirical, non-peer-reviewed, not published in English, or lacking relevance to PCPL or teacher professionalism were excluded from the review.

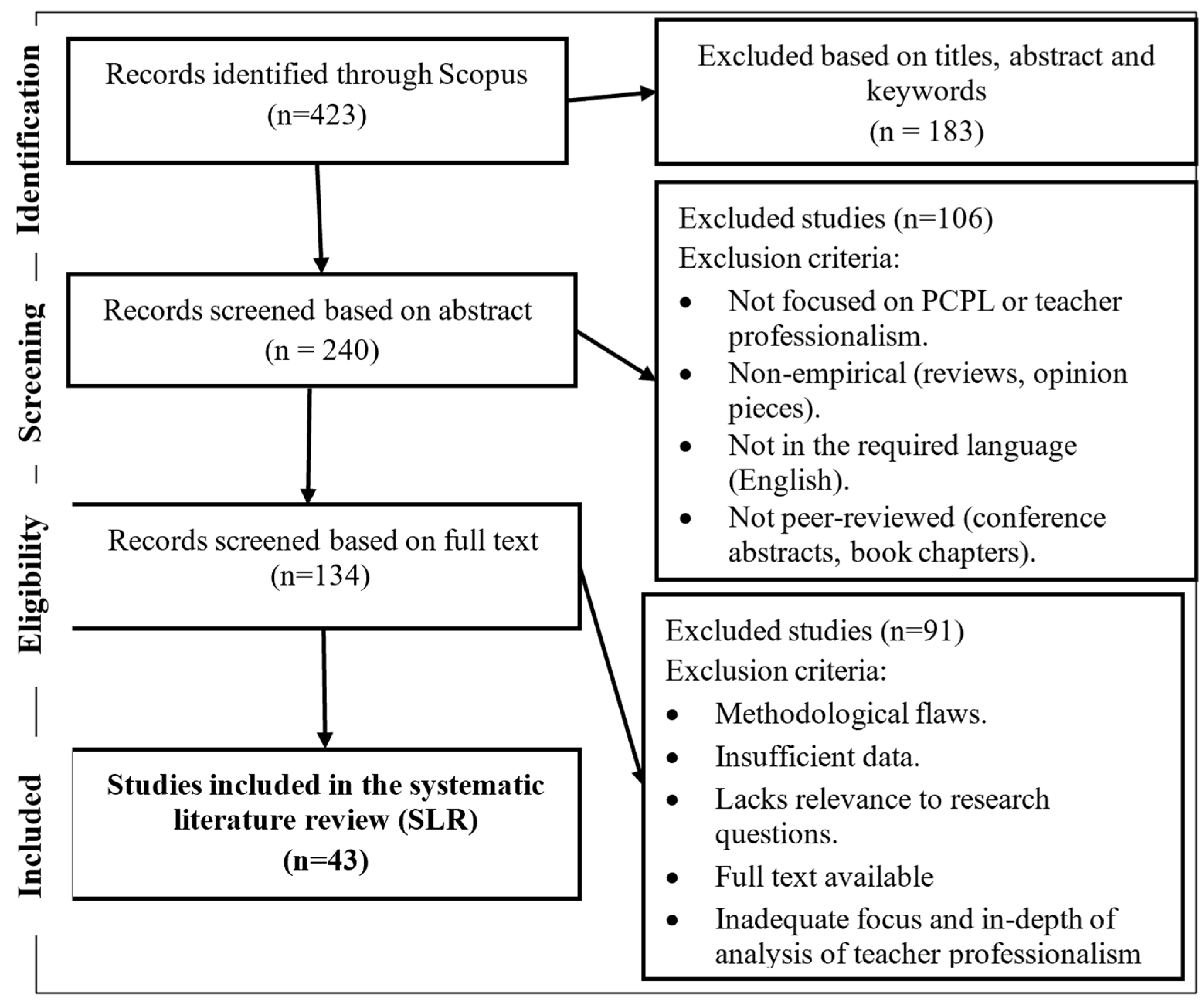

2.2. PRISMA Flow Diagram and Study Selection Process

- Identification: An initial search in Scopus generated 423 articles. Following a review of titles, abstracts, and keywords, 183 records were excluded for not addressing core themes such as PCPL, teacher professionalism, or relevant frameworks.

- Screening: Of the remaining 240 records, abstract-based screening led to the exclusion of 106 additional articles, which did not meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included non-empirical content, theoretical discussions, non-peer-reviewed status, and non-English language.

- Eligibility: A full-text review of 134 articles was conducted to assess eligibility based on quality and relevance. 91 studies were excluded due to issues such as methodological limitations, insufficient data, lack of relevance, or inadequate focus on teacher professionalism.

- Inclusion: Ultimately, 43 studies were included, offering comprehensive insights into practical frameworks in PCPL, their integration of professional competencies and job-related components, implementation challenges, and career-stage support.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.4. Sample Background and Demographic Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Addressing RQ1: Practical Frameworks in CPL for Realizing Teacher Professionalism

3.1.1. Reflective and Collaborative Learning Practices

3.1.2. Self-Regulated Learning and Independent Practice to Enhance Self-Assessment

3.1.3. Personalized and Competency-Based Learning

3.1.4. Transfer and Practical Application Frameworks

3.1.5. Digital Literacy and Technology-Enhanced Frameworks

3.1.6. Context-Specific and Flexible Frameworks

3.1.7. Synthesized Insights for Practical Frameworks in PCPL

3.2. Addressing RQ2: Integration of Multidimensional Professional Competencies and Job-Related Components in PCPL Frameworks for Guiding Teachers’ Continuing Professional Learning (CPL)

3.2.1. Professional Competencies

3.2.2. Job-Related Components

3.2.3. Synthesized Insights for Integrating Multidimensional Competencies in PCPL

3.3. Addressing RQ3: Challenges in Implementing Practical Frameworks in PCPL and Solutions for Enhanced Effectiveness Across Career-Stage Support

3.3.1. Resource and Accessibility Constraints

3.3.2. Organizational and Structural Barriers

3.3.3. Adaptability to Specific Teaching Contexts

3.3.4. Competency-Focused Support for High-Needs Environments

3.3.5. Integration of Digital Tools and Data Analytics

3.3.6. Synthesized Insights for Addressing Implementation Challenges in PCPL Frameworks with Career-Stage Support

4. Discussion

5. Implications

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Policy Implications

6. Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location in Manuscript |

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Title page |

| Abstract | 2 | Structured summary following PRISMA Abstract guidelines. | Abstract |

| Rationale | 3 | Describe rationale for the review in context of existing knowledge. | Introduction |

| Objectives | 4 | State explicit objectives/questions. | Introduction—Research Questions |

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify inclusion/exclusion criteria and grouping of studies. | Methods—Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all sources searched, with last search date. | Methods—Search Strategy (Scopus, 2014–2024) |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present full search strategies for all databases and filters used. | Methods—Search Terms |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify methods used to determine study inclusion. | Methods—PRISMA Flow Diagram & Screening Process |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify methods used to collect data from reports. | Methods—Data Extraction and Synthesis |

| Data items (Outcomes) | 10a | List and define outcomes sought. | Methods—Data Extraction (RQ-linked outcomes) |

| Data items (Other variables) | 10b | List other variables sought and assumptions about missing data. | Methods—Data Extraction |

| Risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify methods/tools used for bias assessment. | Not applicable—qualitative/narrative synthesis only. |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify effect measures used for outcomes. | Not applicable—no effect size calculations performed. |

| Synthesis eligibility | 13a | Describe process for determining which studies were eligible for each synthesis. | Methods—Synthesis Procedure |

| Data preparation | 13b | Describe methods for data preparation. | Methods—Narrative Synthesis |

| Presentation methods | 13c | Describe methods used to tabulate/visualize results. | Tables and thematic synthesis |

| Synthesis methods | 13d | Describe synthesis methods and rationale. | Methods—Narrative/Thematic Synthesis |

| Heterogeneity exploration | 13e | Describe methods to explore heterogeneity. | Not applicable |

| Sensitivity analyses | 13f | Describe sensitivity analyses conducted. | Not applicable |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe methods used to assess reporting bias. | Not applicable |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe methods to assess certainty/confidence. | Not applicable |

| Study selection results | 16a | Describe search results and selection process, ideally with flow diagram. | Methods—PRISMA Flow Diagram |

| Excluded studies | 16b | Cite studies excluded and why. | Methods—Reasons for Exclusion |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present characteristics. | Table 1—Background Characteristics |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present risk of bias assessment. | Not applicable |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | Present summary statistics and effect estimates where appropriate. | Results—Findings per RQ |

| Synthesis summaries | 20a | Summarise characteristics and risk of bias for each synthesis. | Results—Thematic Synthesis |

| Synthesis results | 20b | Present results of all syntheses; if meta-analysis, provide estimates. | Results—Narrative Synthesis |

| Heterogeneity causes | 20c | Present investigations of heterogeneity. | Not applicable |

| Sensitivity analyses | 20d | Present sensitivity analyses. | Not applicable |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessment of reporting bias. | Not applicable |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present certainty assessments. | Not applicable |

| Discussion—Interpretation | 23a | Interpret results in context of other evidence. | Discussion |

| Discussion—Evidence limitations | 23b | Discuss limitations of included evidence. | Discussion—Limitations |

| Discussion—Review process limitations | 23c | Discuss limitations of review process. | Discussion—Limitations |

| Discussion—Implications | 23d | Discuss implications for policy, practice, research. | Discussion—Implications |

| Registration | 24a | Provide registration information or state unregistered. | Not registered—stated in Methods |

| Protocol | 24b | State where protocol can be accessed or that none was prepared. | No protocol prepared. |

| Amendments | 24c | Describe and explain protocol amendments. | Not applicable |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of support and role of funders. | Funding Statement |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare competing interests. | Conflicts of Interest Statement |

| Availability of data | 27 | Report public availability of data, forms, analysis code, materials. | Not applicable—qualitative synthesis; no datasets generated. |

References

- Alamri, H. A., & Alfayez, A. A. (2023). Preservice teachers’ experiences of observing their teaching competencies via self-recorded videos in a personalized learning environment. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. (2022). Using gamification strategies to cultivate and measure professional educator dispositions. In Research anthology on developments in gamification and game-based learning (pp. 1727–1742). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D. P. (2024). Teacher professional development through Knotworking: Facilitating transformational agency through collaboration to overcome constraints to teaching in relation to disruptive events. Professional Development in Education, 50(6), 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K., Tlili, A., & Salha, S. (2024). Human-Machine symbiosis in educational leadership in the era of artificial intelligence (AI): Where are we heading? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 17411432241292295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O. (2024). The personalized continuing professional learning of teachers: A global perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., Hadad, S., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Blau, I. (2023). Formal and informal professional development during different COVID-19 periods: The role of teachers’ career stages. Professional Development in Education, 51, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Herscu, O. (2020). Formal professional development as perceived by teachers in different professional life periods. Professional Development in Education, 46(5), 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M., Ng-Knight, T., & Hayes, B. (2017). Autonomy-supportive teaching and its antecedents: Differences between teachers and teaching assistants and the predictive role of perceived competence. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(4), 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, N. (2022). Adaptive professional development during the pandemic. Designs for Learning, 14(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M. L., & Walkington, C. (2018). The role of situational interest in personalized learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(6), 864–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, M., Adams, G., Perry, E., & Booth, J. (2023). Re-imagining transformative professional learning for critical teacher professionalism: A conceptual review. Professional Development in Education, 49(4), 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V., Woolcott, G., Peddell, L., Yeigh, T., Lynch, D., Ellis, D., Markopoulos, C., Willis, R., & Samojlowicz, D. (2020). An online support system for teachers of mathematics in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 30(3), 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpendale, J., Berry, A., Cooper, R., & Mitchell, I. (2024). Balancing fidelity with agency: Understanding the professional development of highly accomplished teachers. Professional Development in Education, 50(5), 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka, C. D., & McConnell, D. (2016). Situated instructional coaching: A case study of faculty professional development. International Journal of STEM Education, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayary, A., Eppard, J., Mohebi, L., Bailey, F., & Thomure, H. (2024). The effectiveness of an online training module for pre-service and in-service teachers: A case study. Journal of Educators Online, 21(3), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, G. M., Ritzen, H. T. M., Pieters, J. M., & Kuiper, W. A. J. M. (2019). Effective curricula for at-risk students in vocational education: A study of teachers’ practice. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 11(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, M. P., & Girotto, M. (2022). Ethical behavior in leadership: A bibliometric review of the last three decades. Ethics & Behavior, 32(2), 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, L., Bradford, A., & Linn, M. C. (2022). Supporting teachers to customize curriculum for self-directed learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 31(5), 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierez, S. B. (2019). Learning from teaching: Teacher sense-making on their research and school-based professional development. Issues in Educational Research, 29(4), 1181–1200. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342475911 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Hayes, K. N., Inouye, C., Bae, C. L., & Toven-Lindsey, B. (2021). How facilitating K–12 professional development shapes science faculty’s instructional change. Science Education, 105(2), 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaysman, O., & Kramarski, B. (2022). Promoting teachers’ in-class SRL practices: Effects of authentic interactive dynamic experiences (AIDE) based on simulations and video. Instructional Science, 50(6), 829–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, G., Assunção Flores, M., & Niklasson, L. (2013). Teacher quality, professionalism and professional development: Findings from a European project. Teacher Development, 17(4), 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R., & Coiro, J. (2019). Design features of a professional development program in digital literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(4), 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Zhang, T., & Huang, Y. (2020). Effects of school organizational conditions on teacher professional learning in China: The mediating role of teacher self-efficacy. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 66, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J., Scornavacco, K., Clevenger, C., Suresh, A., & Sumner, T. (2024). Automated feedback on discourse moves: Teachers’ perceived utility of a professional learning tool. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(4), 1307–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükaydin, M. A., Çopur, E., Altunkaynak, M., Yildiz, B., Türkmenoglu, M., Ulum, H., & Ulum, Ö. G. (2024). An investigation of the effects of out-of-school learning environments-based teaching on pedagogical belief systems and practices. SAGE Open, 14(1), n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. L., & Hwang, G. J. (2015). An interactive peer-assessment criteria development approach to improving students’ art design performance using handheld devices. Computers & Education, 85, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L., Lien, V. P., Hung, L. T., & Vy, N. T. P. (2024). Impact of professional development activities on teachers’ formative assessment practices. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 13(5), 3028–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Huh, Y., Lin, C. Y., & Reigeluth, C. M. (2022). Personalized learning practice in US learner-centered schools. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(4), ep385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, J. A., Dubois, S. L., Nixon, R. S., & Campbell, B. K. (2015). Supporting newly hired teachers of science: Attaining teacher professional standards. Studies in Science Education, 51(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N., Xin, S., & Du, J. Y. (2018). A peer coaching-based professional development approach to improving the learning participation and learning design skills of in-service teachers. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(2), 291–304. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26388408 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Nawab, A. (2020). Perceptions of the key stakeholders on professional development of teachers in rural Pakistan. SAGE Open, 10(4), 2158244020982614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., & Brown, M. (2022). Learning by doing: Evaluating the key features of a professional development intervention for teachers in data-use, as part of whole school self-evaluation process. Professional Development in Education, 48(2), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofson, M. W., Downes, J. M., Petrick Smith, C., LeGeros, L., & Bishop, P. A. (2018). An instrument to measure teacher practices to support personalized learning in the middle grades. RMLE Online, 41(7), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patall, E. A., & Zambrano, J. (2019). Facilitating student outcomes by supporting autonomy: Implications for practice and policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prain, V., Muir, T., Lovejoy, V., Farrelly, C., Emery, S., & Thomas, D. (2022). Teacher professional learning in large teaching spaces: An Australian case study. Issues in Educational Research, 32(4), 1548–1566. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/102.100.100/548190 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Sasson, I., & Miedijensky, S. (2023). Transfer skills in teacher training programs: The question of assessment. Professional Development in Education, 49(2), 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J. (2021). Beyond the workshop: An interpretive case study of the professional learning of three elementary music teachers. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(3), 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromholt, S., Wiggins, B., & Von der Mehden, B. (2024). Practice-based teacher education benefits graduate trainees and their students through inclusive and active teaching methods. Journal for STEM Education Research, 7(1), 29–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, R., Ryker, K., Viskupic, K., Czajka, C. D., & Manduca, C. (2020). Transforming education with community-developed teaching materials: Evidence from direct observations of STEM college classrooms. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslo, S., Thurston, M., Lerum, Ø., Mandelid, M. B., Jenssen, E. S., Resaland, G. K., & Tjomsland, H. E. (2023). Teachers’ sensemaking of physically active learning: A qualitative study of primary and secondary school teachers participating in a continuing professional development program in Norway. Teaching and Teacher Education, 127, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, O., Christensen, R., Drossel, K., Friesen, S., Forkosh-Baruch, A., & Phillips, M. (2024). Drivers of digital realities for ongoing teacher professional learning. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 29(4), 1851–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulowitzki, P. (2021). Cultivating a global professional learning network through a blended-learning program–levers and barriers to success. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 6(2), 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, G., Urbina, S., & Forteza, D. (2019). Rubric-based formative assessment in process ePortfolio: Towards self-regulated learning. Digital Education Review, 35, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Chang, Y. C., & Gao, H. (2024). Principal support on teacher professional development and mediating role of career calling: Higher education vocational college teachers’ perceptions. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(7), 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K., & Jung, H. (2023). Positive and negative effects of close-knit relationships among teachers in a community of practice. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 30(6), 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Shi, Q., & Lin, E. (2020). Professional development needs, support, and barriers: TALIS US new and veteran teachers’ perspectives. Professional Development in Education, 46(3), 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Values | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2015–2019 | 15 | 35% |

| 2020–2024 | 28 | 65% | |

| Study Context | K-12 Education | 25 | 58% |

| Higher Education | 12 | 28% | |

| Vocational Training | 6 | 14% | |

| Research methods | Qualitative | 18 | 42% |

| Quantitative | 14 | 33% | |

| Mixed Methods | 11 | 25% | |

| Research methods | Teachers | 36 | 84% |

| Principals/Administrators | 5 | 12% | |

| Students | 2 | 4% | |

| Topic/Theme | Teacher Professionalism | 20 | 47% |

| Professional Development Implementation | 10 | 23% | |

| Collaboration & Networks | 8 | 19% | |

| Digital Tools | 5 | 12% | |

| Region | North America | 13 | 30.2% |

| Europe | 5 | 11.6% | |

| Asia-Pacific | 17 | 39.5% | |

| Middle East | 7 | 16.3% | |

| Not Specified | 1 | 2.3% |

| Job-Related Components | Means of Action | Networks of Action | Role Constraints | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession Components | ||||

| Systematic Knowledge and Intellectual Skills | Disciplinary and Pedagogical Knowledge and Skills Goal: Attend a workshop on integrating technology into science teaching to enhance instructional skills. | Pedagogical and Multi-Disciplinary Dialogue Goal: Initiate a monthly meeting with the history department to explore interdisciplinary teaching opportunities, integrating historical context into science lessons. | Curriculum Development and Evaluation Goal: Develop a personal teaching portfolio to document interdisciplinary lessons and evaluate their effectiveness. | |

| Creating New Knowledge; Lifelong Learning | Practical Experience, Reflection, and Independent Learning Goal: Design and implement a project-based module combining science and history, reflecting on its impact on student engagement. | Teamwork and Collaborative Learning Goal: Collaborate with the history department on a cross-disciplinary plan incorporating science and social studies elements. | Adapting to New and Changing Needs Goal: Adapt science curriculum to include historical case studies and tech advancements. | |

| Norms, Values, and Code of Ethics | Professional Autonomy and Commitment to Ethical Practices Goal: Mentor a new teacher, promoting ethical practices in classroom management and student assessment. | Commitment to Students and Colleagues Goal: Strengthen relationships with colleagues and support collaborative PD within the school. | Developing Leadership and Responsibility Goal: Lead a teacher workshop on interdisciplinary teaching and share practices with colleagues. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avidov-Ungar, O. Empowering Teacher Professionalism Through Personalized Continuing Professional Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using a Multidimensional Approach to Self-Assessment and Growth. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121686

Avidov-Ungar O. Empowering Teacher Professionalism Through Personalized Continuing Professional Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using a Multidimensional Approach to Self-Assessment and Growth. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121686

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvidov-Ungar, Orit. 2025. "Empowering Teacher Professionalism Through Personalized Continuing Professional Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using a Multidimensional Approach to Self-Assessment and Growth" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121686

APA StyleAvidov-Ungar, O. (2025). Empowering Teacher Professionalism Through Personalized Continuing Professional Learning: A Systematic Literature Review Using a Multidimensional Approach to Self-Assessment and Growth. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121686