Integrating Systems Thinking into Sustainability Education: An Overview with Educator-Focused Guidance

Abstract

1. Introduction

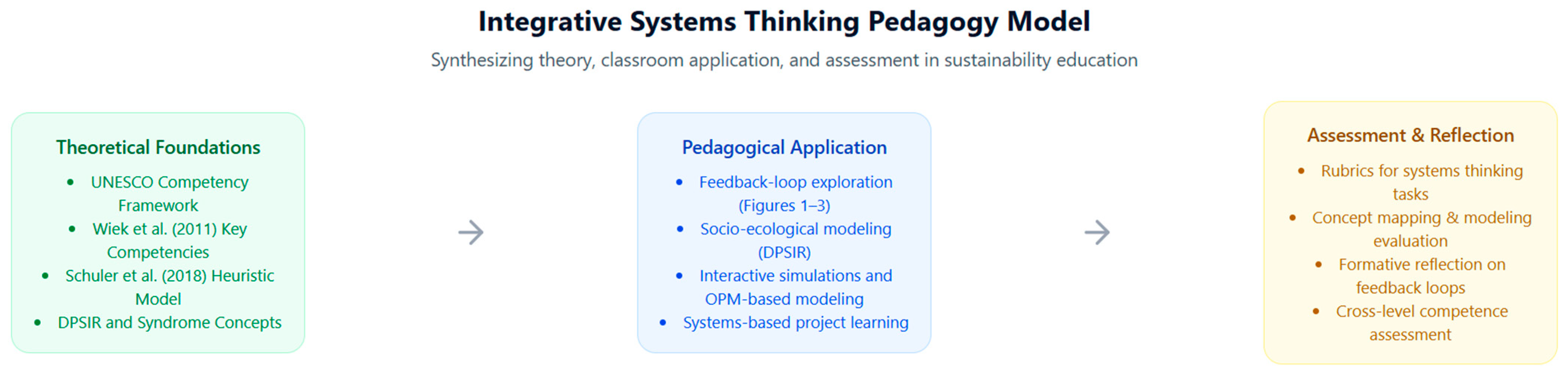

2. Theoretical Framework: Systems Thinking as a Key Competency

2.1. Defining Systems Thinking in Sustainability Education

- Identify system elements and interdependencies: Recognize the key components of a system and the varied interrelations among those components. For instance, in a climate system, components might include greenhouse gas emissions, atmospheric temperature, ice cover, and human activities, all of which are linked.

- Recognize dynamic processes and temporal dimensions: Understand that systems change over time, sometimes rapidly and sometimes gradually, and be able to consider time delays, historical trends, or future projections. For example, the effects of a policy on an ecosystem might not be immediate, reflecting a time lag in the system’s response.

- Construct and use mental or conceptual models: Build internal or external representations, such as diagrams and simulations of complex real-world phenomena, to explain how the system works. Modeling can range from a simple causal loop diagram to a complex computer simulation; the key is to organize one’s understanding of the system’s structure.

- Explain, predict, and strategize based on systems knowledge: Use understanding of a system to explain observed behavior, make predictions (or plausible forecasts), and develop solutions or interventions. In sustainability, this might mean forecasting how an ecosystem will respond to a disturbance or designing a policy intervention that leverages feedback loops to achieve a positive outcome.

2.2. A Heuristic Competence Model for Systems Thinking

- Declarative Systems Knowledge—understanding core systems theory concepts and knowledge of specific system characteristics. This includes being aware of general system properties (e.g., hierarchies, feedback types, non-linearity) and being familiar with specific complex systems (such as climate, ecosystems, or urban systems). It is essentially the factual and conceptual knowledge base about systems.

- Systems Modeling is the ability to create and interpret system models. This involves understanding interactions within systems and representing them through qualitative models (like causal loop diagrams or influence diagrams) or simple quantitative models. A student strong in this dimension can map out how different parts of a system connect and possibly quantify the relationships between them.

- Solving Problems Using System Models—This aspect of systems thinking centers on reasoning and problem-solving using system models to explain phenomena, forecast system behavior, and design solutions for complex challenges. For instance, with an energy systems model, a learner could predict how boosting renewable energy adoption would impact carbon emissions or energy prices and then craft strategies in response.

- Evaluating System Models—The Critical Appraisal of System Models. Learners must be able to assess whether a model accurately represents reality, check its assumptions and limitations, and evaluate the uncertainty in its predictions. This competence guards against seeing models as infallible—students learn to ask, “How reliable is this model? Does it fit the empirical data? What happens if conditions change?”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Rationale for the Narrative Approach

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Selection Process and Inclusion Logic

- Conceptual significance—influential theoretical or competence frameworks (e.g., UNESCO, 2017; Wiek et al., 2011).

- Empirical rigor—peer-reviewed studies reporting explicit instructional or assessment interventions, as well as reports and position papers issued by reputable international organizations or research bodies (e.g., UNESCO, OECD, World Bank, or equivalent institutions).

- Pedagogical relevance—clear implications for teacher education or classroom practice.

- Diversity of context—representation of both K–12 and higher-education implementations.

3.4. Data Extraction and Thematic Synthesis

- educational level and context;

- systems thinking dimension(s) targeted;

- pedagogical strategies or tools employed (e.g., conceptual modeling, simulations, socio-scientific issues);

- reported learning outcomes or assessment methods.

3.5. Reflexivity and Limitations

4. Findings

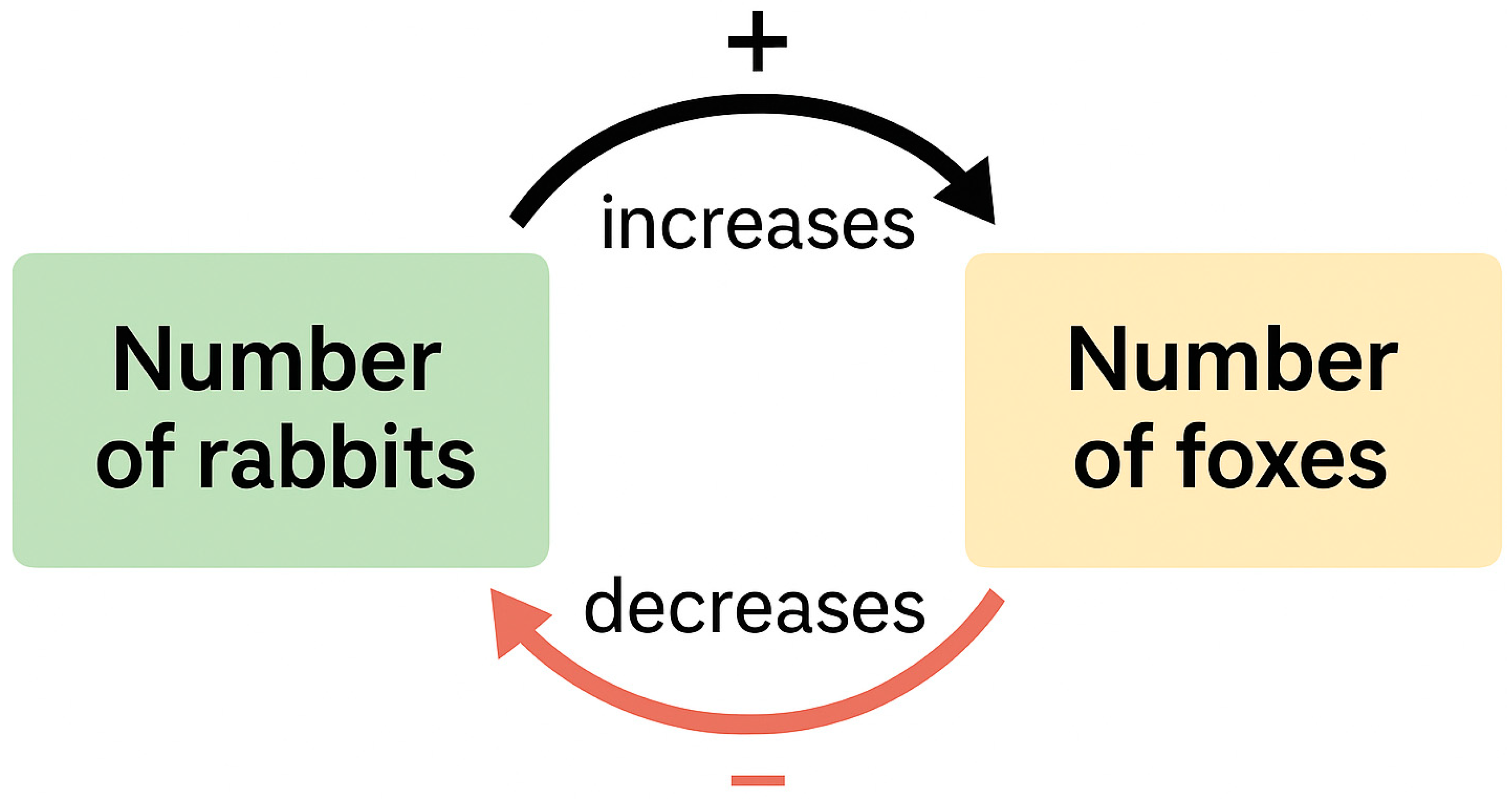

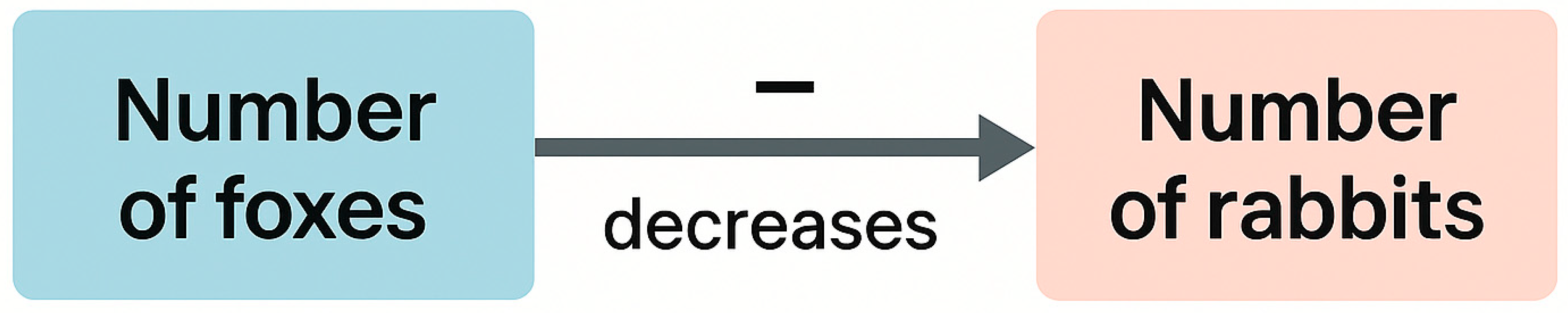

4.1. Bridging Scientific and Social Systems Through Feedback Loops

- Rising Temperatures

- 2.

- Increased Evaporation

- 3.

- More Water Vapor in the Atmosphere

- 4.

- Enhanced Greenhouse Effect

- 5.

- Loop Reinforcement

4.2. Case Examples in K–12 and Higher Education

4.2.1. K–12 Case: Ecosystems and Human Impact in Middle School

4.2.2. Higher Education Case: Pre-Service Teacher Training and Task Design

4.2.3. Other Examples and Strategies

5. Implications for Pedagogy and Curriculum

6. Limitations

7. Directions for Future Research

- Systematic Mapping of the Field: Conduct systematic and scoping reviews using established protocols (e.g., PRISMA) to capture the full range of literature on systems thinking in sustainability education, identify emerging trends, and highlight under-studied areas (Gutierrez-Bucheli et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2025).

- Robust Empirical Evaluations: Implement randomized controlled trials, longitudinal mixed-methods studies, and quasi-experimental designs to evaluate specific pedagogical interventions, quantify learning outcomes, and examine the durability of systems thinking skills over time (Demssie et al., 2023).

- Cross-Cultural and Contextual Studies: Explore how systems thinking competencies develop and manifest in varied educational settings, such as non-Western schools, informal learning environments, and fully online contexts, to ensure findings are globally relevant.

- Validation of Assessment Instruments: Refine and validate tools for measuring systems thinking (e.g., concept-mapping rubrics, modeling assessments) across different age groups, disciplines, and instructional modes to establish their reliability and generalizability (Minichiello & Caldwell, 2021).

- Integration of Emerging Technologies: Investigate the potential of virtual simulations, augmented reality, and AI-driven platforms to scaffold systems thinking instruction, provide adaptive feedback, and personalize learning pathways in sustainability education.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

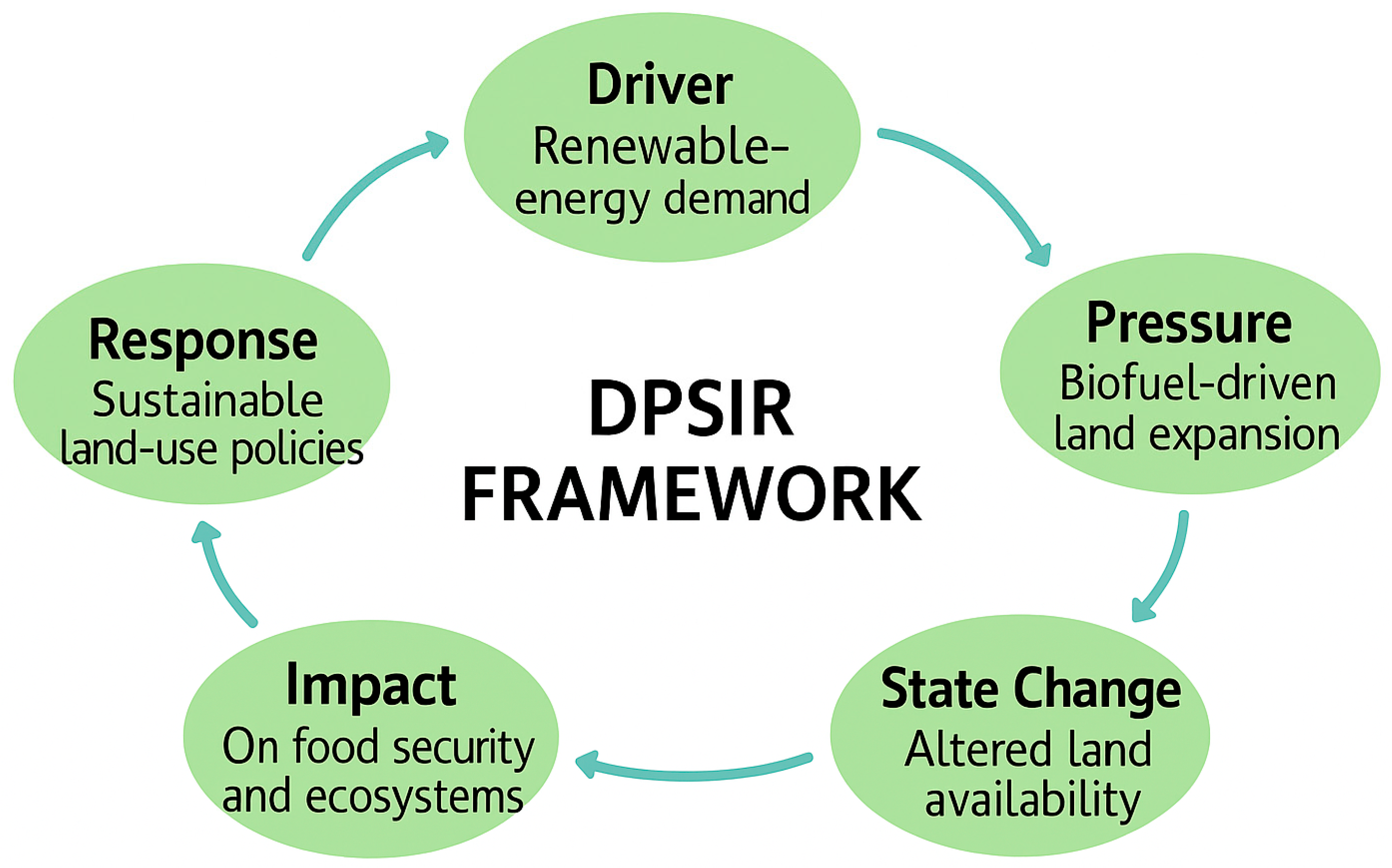

| DPSIR | Driver–Pressure–State–Impact–Response |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OPM | Object-Process Methodology |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

Appendix A

| # | Authors (Year) | Journal/Source | Region | Educational Level | Systems Thinking Elements Identified | Pedagogical Proposal/Contribution |

| 1 | Evagorou et al. (2009) | Int. J. of Science Education | Cyprus | Elementary (5th–6th grade) | Interactive ecosystem simulation; cause–effect linkages in food web and human impacts. | Demonstrated that a simulation-based learning environment can help 11–12-year-old students develop systems thinking skills by visualizing how changes in one part of an ecosystem (e.g., adding a pollutant) affect other parts. Students learned to map ecological relationships and saw consequences of management decisions unfold, indicating even young learners can grasp complex system dynamics with appropriate tools. |

| 2 | Riess and Mischo (2010) | Int. J. of Science Education | Germany | Secondary (Biology classes) | Modeling and describing complex biological systems; identifying interdependencies in ecosystems. | Analyzed teaching approaches in biology lessons to promote systems thinking, defined as “the ability to recognise, describe, model… and explain complex aspects of reality as systems”. Found that integrating cross-topic connections in biology (e.g., linking ecological and social factors) can improve students’ ability to understand and explain biological phenomena systemically, supporting the value of systems-oriented teaching in science. |

| 3 | Ponto and Linder (2011) | Curriculum Guide (Pacific Education Institute) | USA | High school (Grades 9–12) | System mapping of environmental issues; cause–effect chains in nature and society. | A curriculum guide (“Sustainable Tomorrow”) providing project-based learning units for environmental education. It offers activities for students to draw systems maps connecting natural processes (wildlife, habitat) and human factors, thereby helping teachers integrate systems thinking (e.g., food webs + land use) into high-school curricula. This guide emphasizes visual mapping and discussion of “systems of systems” to foster holistic understanding. |

| 4 | Wiek et al. (2011) | Sustainability Science | Global | Higher education (university programs) | Key competencies framework (systems thinking as one of 5 sustainability competencies). | Proposed a widely used competency framework for sustainability education, identifying systems thinking as a core competency alongside futures, values, strategic, and collaboration skills. This framework has informed curriculum development in universities by emphasizing the ability to understand interconnected environmental, social, and economic systems as essential for all sustainability professionals. |

| 5 | Brandstädter et al. (2012) | Int. J. of Science Education | Germany | Secondary (High school biology) | Concept mapping of system components and interactions; assessment of systemic understanding. | Examined different concept-mapping practices to assess students’ systems thinking in biology. The study found that concept mapping is an effective tool for eliciting students’ understanding of biological systems. By comparing mapping techniques, they demonstrated that well-designed concept map tasks can validly capture how learners perceive relationships in a system, informing large-scale assessment of systems thinking skills. |

| 6 | Woo et al. (2012) | OIDA Int. J. of Sustainable Development | Malaysia (global review) | Higher education (curriculum review) | Characteristics of ESD curriculum (holistic integration, interdisciplinarity, systems perspective). | Reviewed sustainability curricula and highlighted that effective programs embed sustainability (and systems thinking) as a cross-cutting theme across courses. Emphasized a holistic approach—e.g., “spiral curriculum” revisiting core concepts with increasing system complexity—to help students progressively build systemic understanding of issues like water, energy, and community development. |

| 7 | Burmeister and Eilks (2013) | Science Education International | Germany | Teacher education (pre-service & trainee teachers) | Understanding of sustainability and ESD concepts (systems aspect implicit). | This study surveyed German chemistry student teachers and trainees, revealing a fragmented understanding of sustainability and ESD. The findings highlight the difficulty of linking scientific content to broader systems without explicit training. The study underscores the importance of professional development to strengthen systems thinking in future educators. |

| 8 | Baldwin et al. (2016) | Ocean & Coastal Management | Thailand (Gulf of Thailand) | Tertiary/Professional training (transdisciplinary) | DPSIR framework (Drivers-Pressures-State-Impact-Response) applied to coastal socio-ecological issues; feedback pathways between society & environment. | This study applied the DPSIR framework in a transdisciplinary training program focused on environmental issues in the Gulf of Thailand. Participants used the model to map human drivers, environmental pressures, impacts, and policy responses, highlighting interconnected feedbacks. The exercise demonstrated that DPSIR diagrams support knowledge exchange and help learners analyze complex sustainability challenges through systemic lenses. |

| 9 | Sweeney (2017) | Book chapter—EarthEd (Island Press) | USA | K–12 (general, curriculum perspective) | Core “systems literacy” concepts (interdependence, feedback loops, system archetypes); use of visual tools (connection circles, causal loop diagrams, simulations). | This chapter advocates for integrating systems thinking throughout K–12 education to develop “systems-smart” learners. It outlines age-appropriate systems concepts, such as emergent behavior, archetypes, and feedback loops, and emphasizes visualization tools like causal-loop diagrams and simulations. The goal is to foster cross-disciplinary thinking so students can approach complex issues with interconnected, systems-based perspectives. |

| 10 | Arnold and Wade (2017) | INCOSE Intl. Symposium (Proc.) | USA (conceptual) | N/A (cross-domain skills framework) | Comprehensive taxonomy of systems thinking skills (e.g., understanding hierarchies, feedback, emergent properties, using visual models). | Defined a complete set of systems thinking skills for engineers and learners, highlighting abilities such as recognizing system boundaries, identifying feedback loops, understanding non-linearity, and employing visual modeling techniques. This skills framework serves as a guide for curriculum designers—stressing, for example, that teaching should include diagramming and modeling activities, since visualizing complex systems is critical for learning to “think in systems”. |

| 11 | Yoon et al. (2017) | Instructional Science | USA | K–12 Teacher Professional Development | Complex systems in science education; computer-supported systems simulations; teacher PD design. | This study developed a professional development (PD) program to support science teachers in teaching complex systems using simulations and modeling tools. It highlighted the need for intensive support and identified effective PD strategies, including hands-on modeling, collaborative lesson design, and coaching. The program improved teachers’ confidence and instructional practices, offering guidance for building educator capacity in systems-based instruction. |

| 12 | UNESCO (2017) | UN SDG: Learn (UNESCO competencies report) | Global | All levels (policy framework) | Systems thinking defined as key sustainability competency (ability to recognize interconnections, handle complexity and uncertainty across scales). | This UNESCO report established systems thinking as a key competency for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. It emphasizes the need for education to foster learners’ ability to analyze complex interactions across environmental, social, and economic systems. The report calls for curricula and teacher training to support holistic, integrative thinking as a central aim of Education for Sustainable Development. |

| 13 | Schuler et al. (2018) | Journal of Geography in Higher Education | Germany | Teacher education (pre-service science teachers) | Four-dimensional systems thinking competence model (knowledge of system characteristics; modeling and simulation; perspective-taking; evaluation of system dynamics). | This study implemented a four-part heuristic model of systems thinking, systems knowledge, modeling skills, perspective-taking, and evaluation, in a teacher education course. Pre-service science teachers created influence diagrams and designed systems-based lessons, leading to marked improvements in their systems thinking and pedagogical approaches. The study demonstrates the effectiveness of structured, multidimensional training for building teachers’ capacity to teach systems thinking. |

| 14 | Lavi and Dori (2019) | Int. J. of Science Education | Israel | Teacher education (pre- vs. in-service teachers) | Object-Process Methodology (OPM) modeling tasks; comparative assessment of systems thinking skills. | This study used conceptual modeling (Object-Process Methodology) to assess and compare systems thinking in pre-service and in-service science and engineering teachers. Findings showed that experienced teachers demonstrated stronger systems thinking, especially in identifying feedback loops and system boundaries. The study underscores the value of modeling-based training in teacher education to close the gap in systems thinking competency between novice and practicing educators. |

| 15 | Happonen et al. (2020) | AIP Conference Proceedings | Finland (case study) | Higher education (university students, interdisciplinary) | Sustainability hackathon project; material flow mapping; stakeholder roles; interdisciplinary teamwork. | This study examined a university sustainability hackathon where interdisciplinary student teams tackled circular economy challenges. Students created system diagrams and reflected on the value of diverse perspectives in understanding complex problems. The hackathon setting fostered systems thinking by requiring collaborative modeling and integration of varied disciplinary insights. |

| 16 | Hong (2020) | Book chapter (SDGs & Higher Education) | USA (university context) | Higher education (faculty development) | Faculty Learning Community model; curriculum infusion of sustainability (across disciplines, systems perspective). | This chapter described how a Faculty Learning Community was used to integrate sustainability across a university curriculum. Through regular cross-disciplinary meetings, faculty collaboratively embedded sustainability, and systems thinking, into diverse courses. The initiative fostered curricular coherence and interdisciplinary connections, demonstrating that faculty collaboration can effectively infuse systems perspectives into higher education. |

| 17 | Ke et al. (2020) | Int. J. of Science Education | USA | Secondary science (socio-scientific issues in class) | Socio-scientific issue (SSI) instruction blending science and social aspects; use of epistemic tools (e.g., evidence charts, system maps) to examine issues. | This study explored how students engaged in systems thinking during a socio-scientific issues (SSIs)–based science unit. When analyzing topics like electric cars, students connected scientific concepts with societal factors using tools such as concept maps and stakeholder charts. The findings show that SSI pedagogy naturally fosters systems thinking by encouraging learners to analyze interdisciplinary, real-world problems. |

| 18 | Lavi et al. (2020) | IEEE Trans. on Education | Israel | Higher education (engineering undergraduates) | Model-Based Systems Thinking (MBST) via OPM; team-based conceptual modeling projects. | This study evaluated engineering student teams’ systems thinking using Object-Process Methodology (OPM) in a cloud-based environment. Teams created conceptual models of engineering systems, which were assessed for systems thinking indicators. Results showed that guided modeling helped students better identify system components, interactions, and constraints. The study validates model-based systems thinking (MBST) as an effective instructional and assessment tool in engineering education. |

| 19 | Karaarslan Semiz (2021) | In MDPI “Transitioning to Quality Education” (theoretical note) | (Literature synthesis—global K–12) | K–12 (science education, general) | Reported outcomes of systems thinking pedagogy: student ability to explain causal chains, DPSIR framework usage for environmental issues. | This theoretical review emphasizes that K–12 students exposed to systems thinking pedagogy demonstrate deeper, more coherent understanding of complex issues. Using frameworks like DPSIR, students articulate cause–effect chains rather than isolated facts, showing enhanced engagement and explanatory clarity. The review highlights systems thinking as a powerful approach for improving science education outcomes. |

| 20 | Dugan et al. (2021) | ASEE Conference Proceedings | USA | Higher education (engineering education) | Assessment approaches for systems thinking (concept maps, scenario analysis, engagement measures). | This review examined assessment methods for evaluating systems thinking in engineering education. It critiqued conventional tests as inadequate and proposed alternatives like concept mapping, case analysis, and think-aloud protocols. Dugan et al. emphasized the importance of authentic, open-ended tasks with clear rubrics to capture students’ systemic understanding, guiding more effective evaluation practices in project-based learning. |

| 21 | Mahaffy and Elgersma (2022) | Current Opinion in Green & Sust. Chemistry | Canada/USA | Higher education (chemistry curriculum) | Planetary Boundaries framework linked to chemistry; molecular-level to global system connections. | This paper advocates integrating systems thinking and planetary boundaries as core competencies in chemistry education. It proposes redesigning curricula to connect molecular science with global sustainability through concepts like feedbacks and thresholds. The contribution lies in offering a conceptual model to embed macro-level sustainability into chemistry teaching, equipping students with both disciplinary depth and systemic insight. |

| 22 | Annelin and Boström (2023) | Int. J. of Sustainability in Higher Ed. | Sweden (global review) | Higher education (competency assessment) | Measurement of sustainability competencies (including systems thinking); review of assessment scales and validation. | This review examined tools for assessing sustainability competencies, including systems thinking. It found diverse but inconsistent instruments, often lacking validation. The authors recommend developing assessments that capture dynamic system understanding, not just content recall. The study contributes by offering guidance for improving the reliability of systems thinking evaluation in educational programs. |

| 23 | Demssie et al. (2023) | Environmental Education Research | Ethiopia/Netherlands (case study) | Secondary education (real-world learning program) | Multiple real-world learning approaches (project-based learning, community projects, field-based inquiry) to foster systems thinking. | This case study evaluated a program using real-world sustainability learning—like fieldwork and interdisciplinary projects—to foster systems thinking. Students showed improved ability to recognize systemic relationships and develop integrated solutions. The findings underscore the effectiveness of authentic, multi-context learning experiences in developing systems thinking competencies. |

| 24 | Peretz et al. (2023a) | Education Sciences | Israel | Teacher professional development (Chemistry teachers) | Rubric-guided task design for systems-oriented learning; system aspects in science tasks; feedback loops in food system context. | This study explored how chemistry teachers learn to design assessments that integrate sustainability and systems thinking. Through a professional development course, teachers improved their ability to connect chemistry with broader systems using guiding questions and visual diagrams. A key outcome was a validated rubric for sustainability-oriented tasks, demonstrating that targeted training enhances teachers’ skills in promoting systems thinking. |

| 25 | Peretz et al. (2023b) | Instructional Science | Israel | Higher education & Teacher education (Engineering and science students; teachers) | Conceptual modeling (OPM) in an online platform; interdisciplinary systems tasks; comparative study across students and teachers. | This study examined a web-based modeling intervention (using OPCloud) to develop systems thinking in engineering and science students, as well as educators. Participants improved in identifying system components, interactions, and feedback loops. Engineering students integrated social–technical elements in their designs, while teachers enhanced their guidance of systemic problem analysis. The study supports model-based exercises as effective pedagogy for advancing systems thinking across education levels. |

| 26 | Peretz et al. (2024) | IEEE Trans. on Education | Israel | Higher education (Engineering undergraduates) | Online learning tasks with OPM modeling; assessment of systems thinking in an engineering course. | This study evaluated engineering students’ systems thinking through online modeling tasks using Object-Process Methodology (OPM) on the OPCloud platform. By analyzing students’ digital models, researchers assessed their understanding of system components, interactions, and emergent behaviors. Findings show that model-based assignments can effectively foster and assess systems thinking in large-scale online courses, offering a scalable approach to teaching complex systems in engineering education. |

| 27 | Pilcher (2024) | Physical Sciences Reviews | South Africa | Higher education (Tertiary chemistry) | Integration of systems thinking into chemistry curriculum; linking chemistry concepts to global sustainability frameworks (e.g., planetary boundaries). | Pilcher provides a roadmap for integrating systems thinking into university-level chemistry education, aligning with IUPAC’s call for reform. The article outlines strategies such as life-cycle analysis, contextualizing chemistry within the Planetary Boundaries framework, and using cross-disciplinary case studies. |

References

- Allen, K. J., Reide, F., Gouramanis, C., Keenan, B., Stoffel, M., Hu, A., & Ionita, M. (2022). Coupled insights from the palaeoenvironmental, historical and archaeological archives to support social-ecological resilience and the sustainable development goals. Environmental Research Letters, 17(5), 055011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annelin, A., & Boström, G.-O. (2023). An assessment of key sustainability competencies: A review of scales and propositions for validation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(9), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinze, E. D. (2024). Unravelling exponential growth dynamics: A comprehensive review. IAA Journal of Scientific Research, 11(3), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R. D., & Wade, J. P. (2017). A complete set of systems thinking skills. INCOSE International Symposium, 27(1), 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J. P., Burdon, D., Elliott, M., & Gregory, A. J. (2011a). Management of the marine environment: Integrating ecosystem services and societal benefits with the DPSIR framework in a systems approach. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62(2), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J. P., Gregory, A. J., Burdon, D., & Elliott, M. (2011b). Managing the marine environment: Is the DPSIR framework holistic enough? Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 28(5), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C., Lewison, R. L., Lieske, S. N., Beger, M., Hines, E., Dearden, P., Rudd, M. A., Jones, C., Satumanatpan, S., & Junchompoo, C. (2016). Using the DPSIR framework for transdisciplinary training and knowledge elicitation in the gulf of Thailand. Ocean & Coastal Management, 134, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstädter, K., Harms, U., & Großschedl, J. (2012). Assessing system thinking through different concept-mapping practices. International Journal of Science Education, 34(14), 2147–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, M., & Eilks, I. (2013). An understanding of sustainability and education for sustainable development among German student teachers and trainee teachers of chemistry. Science Education International, 24(2), 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J. A. (2016). Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 1(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnohan, S. A., Trier, X., Liu, S., Clausen, L. P. W., Clifford-Holmes, J. K., Hansen, S. F., Benini, L., & McKnight, U. S. (2023). Next generation application of DPSIR for sustainable policy implementation. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 5, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demssie, Y. N., Biemans, H. J. A., Wesselink, R., & Mulder, M. (2023). Fostering students’ systems thinking competence for sustainability by using multiple real-world learning approaches. Environmental Education Research, 29(2), 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D., Blok, V., Lans, T., & Wesselink, R. (2012). Developing human capital for agri-food firms’ multi-stakeholder interactions. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M., Lu, J., Wang, G., Zheng, X., & Kiritsis, D. (2022, April 25–28). Model-based systems engineering papers analysis based on word cloud visualization. 2022 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon) (pp. 1–7), Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dori, D. (2016). Model-based systems engineering with OPM and SysML. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, K. E., Mosyjowski, E. A., Daly, S. R., & Lattuca, L. R. (2021, July 26–29). Systems thinking assessments: Approaches that examine engagement in systems thinking. ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Paper ID #32549, Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- Eilks, I., & Hofstein, A. (2014). Combining the question of the relevance of science education with the idea of education for sustainable development. In I. Eilks, S. Markic, & B. Ralle (Eds.), Science education research and education for sustainable development (pp. 3–14). Shaker. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evagorou, M., Korfiatis, K., Nicolaou, C., & Constantinou, C. (2009). An investigation of the potential of interactive simulations for developing system thinking skills in elementary school: A case study with fifth-graders and sixth-graders. International Journal of Science Education, 31(5), 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gari, S. R., Newton, A., & Icely, J. D. (2015). A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems. Ocean & Coastal Management, 103, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Doménech, D., Magomedova, N., Sánchez-Alcázar, E. J., & Lafuente-Lechuga, M. (2021). Integrating sustainability in the business administration and management curriculum: A sustainability competencies map. Sustainability, 13(16), 9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D. J., Nilsson, M., Stevance, A., & McCollum, D. (2017). A guide to SDG interactions: From science to implementation (Vol. 33, Issue 7, pp. 1–239). International Council for Science (ISC). [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Bucheli, L., Reid, A., & Kidman, G. (2022). Scoping reviews: Their development and application in environmental and sustainability education research. Environmental Education Research, 28(5), 645–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happonen, A., Minashkina, D., Nolte, A., & Angarita, M. A. M. (2020). Hackathons as a company—University collaboration tool to boost circularity innovations and digitalization enhanced sustainability. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2233, 050009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, R. M. (1999). What is a spiral curriculum? Medical Teacher, 21(2), 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems, 4(5), 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W. (2020). Build it and they will come: The faculty learning community approach to infusing the curriculum with sustainability content. In Sustainable development goals and institutions of higher education (pp. 49–60). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, J. K., & Couch, B. A. (2018). The positive effect of in-class clicker questions on later exams depends on initial student performance level but not question format. Computers & Education, 120, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaarslan Semiz, G. (2021). Systems thinking research in science and sustainability education: A theoretical note. In Transitioning to quality education. MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L., Sadler, T. D., Zangori, L., & Friedrichsen, P. J. (2020). Students’ perceptions of socio-scientific issue-based learning and their appropriation of epistemic tools for systems thinking. International Journal of Science Education, 42(8), 1339–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, J., Eisenack, K., & Scheffran, J. (2006). Marine overexploitation: A syndrome of global change. In Multiple dimensions of global change (pp. 257–284). TERI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lavi, R., & Dori, Y. J. (2019). Systems thinking of pre- and in-service science and engineering teachers. International Journal of Science Education, 41, 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavi, R., Dori, Y. J., Wengrowicz, N., & Dori, D. (2020). Model-based systems thinking: Assessing engineering student teams. IEEE Transactions on Education, 63(1), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, P. G., & Elgersma, A. K. (2022). Systems thinking, the molecular basis of sustainability and the planetary boundaries framework: Complementary core competencies for chemistry education. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 37, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ramos, P., Sánchez-Hernández, E., Fourati-Jamoussi, F., Annelin, A., Charatsari, C., Ferreira-Santos, J., Doran, P., Naves-Sousa, D., Eugenio-Gozalbo, M., Giudice, L. A. L., Oliveira-Pinto, F., & Navas-Gracia, L. M. (2025). Operationalizing the European sustainability competence framework: Development and validation of learning outcomes for GreenComp. Open Research Europe, 5, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (Vol. 41, pp. 31–48). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Introduction: The systems lens. In Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. H. (2015). Leverage points-places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Millican, R. (2022). A rounder sense of purpose: Competences for educators in search of transformation. In Competences in education for sustainable development: Critical perspectives (pp. 35–43). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Minichiello, A., & Caldwell, L. (2021). A narrative review of design-based research in engineering education: Opportunities and challenges. Studies in Engineering Education, 1(2), 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxnes, E. (1998). Overexploitation of renewable resources: The role of misperceptions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 37(1), 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, R., Dori, D., & Dori, Y. J. (2023a). Investigating chemistry teachers’ assessment knowledge via a rubric for self-developed tasks in a food and sustainability context. Education Sciences, 13(3), 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, R., Levi-Soskin, N., Dori, D., & Dori, Y. J. (2024). Assessing engineering students’ systems thinking and modeling based on their online learning. IEEE Transactions on Education, 67(3), 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretz, R., Tal, M., Akiri, E., Dori, D., & Dori, Y. J. (2023b). Fostering engineering and science students’ and teachers’ systems thinking and conceptual modeling skills. Instructional Science: An International Journal of the Learning Sciences, 51(3), 509–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilcher, L. A. (2024). Embedding systems thinking in tertiary chemistry for sustainability. Physical Sciences Reviews, 9(1), 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponto, C. F., & Linder, N. P. (2011). A teachers’ guidebook for applying systems thinking to environmental education curricula for grades 9–12. Pacific Eduation Institute (PEI). [Google Scholar]

- Riess, W., & Mischo, C. (2010). Promoting systems thinking through biology lessons. International Journal of Science Education, 32, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.-J., Piedrahita Guzman, Y., Sosa-Molano, J., Robertson, D., Ahern, S., & Garza, T. (2025). Systematic literature review: A typology of sustainability literacy and environmental literacy. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1490791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellnhuber, H.-J., Block, A., Cassel-Gintz, M., Kropp, J., Lammel, G., Lass, W., Lienenkamp, R., Loose, C., Lüdeke, M. K., Moldenhauer, O., Petschel-Held, G., Plöchl, M., & Reusswig, F. (1997). Syndromes of global change. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 6(1), 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S., Fanta, D., Rosenkraenzer, F., & Riess, W. (2018). Systems thinking within the scope of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)—A heuristic competence model as a basis for (science) teacher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 42(2), 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. M. (1991). The fifth discipline, the art and practice of the learning organization. Performance + Instruction, 30(5), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E., Donche, V., & Van Petegem, P. (2022). Action-orientation in education for sustainable development: Teachers’ interests and instructional practices. Journal of Cleaner Production, 370, 133469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, E., & Weterings, R. (1999). Environmental indicators: Typology and overview (Technical Report No. 25). European Environment Agency (EEA). [Google Scholar]

- Soderquist, C., & Overakker, S. (2010). Education for sustainable development: A systems thinking approach. Global Environmental Research, 14(1), 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhera, J. (2022). Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(4), 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, L. B. (2017). All systems go! Developing a generation of “systems-smart” kids. In Earthed: Rethinking education on a changing planet (pp. 141–153). Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, M., Zreke, D., Hugerat, M., & Hofstein, A. (2023). Chemistry teachers’ awareness of sustainability through social media: Cultural differences. In Y. J. Dori, C. Ngai, & G. Szteinberg (Eds.), Digital learning and teaching in chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. (2017). UNESCO cross-cutting and specialized SDG competencies. UN SDG:Learn. Available online: https://www.unsdglearn.org/unesco-cross-cutting-and-specialized-sdg-competencies/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y. L., Mokhtar, M., Komoo, I., & Azman, N. (2012). Education for sustainable development: A review of characteristics of sustainability curriculum. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development, 3(8), 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S. A., Anderson, E., Koehler-Yom, J., Evans, C., Park, M., Sheldon, J., Schoenfeld, I., Wendel, D., Scheintaub, H., & Klopfer, E. (2017). Teaching about complex systems is no simple matter: Building effective professional development for computer-supported complex systems instruction. Instructional Science, 45(1), 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Framework | Audience | Definition/Description of Systems Thinking | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNESCO (2017) | Students (global) | Recognizing relationships, handling complexity, considering feedback, scales, uncertainty. | International |

| Wiek et al. (2011) | Higher Ed Students | Analyzing complex systems, identifying interdependencies, proposing leverage-oriented interventions. | International |

| EU GreenComp (Martín-Ramos et al., 2025) | Students & Adults | Exploring complexity in sustainability challenges through system interconnections and dynamics. | European Union |

| CRUE (Gil-Doménech et al., 2021) | Higher Ed Institutions | Understanding interactions among ecological, social, and economic subsystems. | Spain |

| A Rounder Sense of Purpose (RSP) (Millican, 2022) | Teachers | Enabling educators to guide learners in examining dynamic systems and interdependencies. | Europe |

| Dentoni et al. (2012) | Managers & HE graduates in agri-food sector | Systems thinking defined as identifying/analyzing (sub)systems across domains, recognizing interdependencies, and understanding wicked sustainability problems; part of a broader 7-competency model for multi-stakeholder sustainability interactions. | International |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peretz, R. Integrating Systems Thinking into Sustainability Education: An Overview with Educator-Focused Guidance. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121685

Peretz R. Integrating Systems Thinking into Sustainability Education: An Overview with Educator-Focused Guidance. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121685

Chicago/Turabian StylePeretz, Roee. 2025. "Integrating Systems Thinking into Sustainability Education: An Overview with Educator-Focused Guidance" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121685

APA StylePeretz, R. (2025). Integrating Systems Thinking into Sustainability Education: An Overview with Educator-Focused Guidance. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121685