Situated Science Education and Curricular Justice in Rural Borderland Schools: Elementary Teachers’ Voices from Northern Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Review of Literature

1.1.1. Professional Demands in the Teaching of Natural Sciences in Elementary Education

1.1.2. Pre-Service Teacher Education for the Teaching of Natural Sciences in Borderland Elementary Education Contexts

1.1.3. Local Environment as a Potential Pedagogical Resource

1.1.4. Research Related to Integrated Learning and Interdisciplinary

2. Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

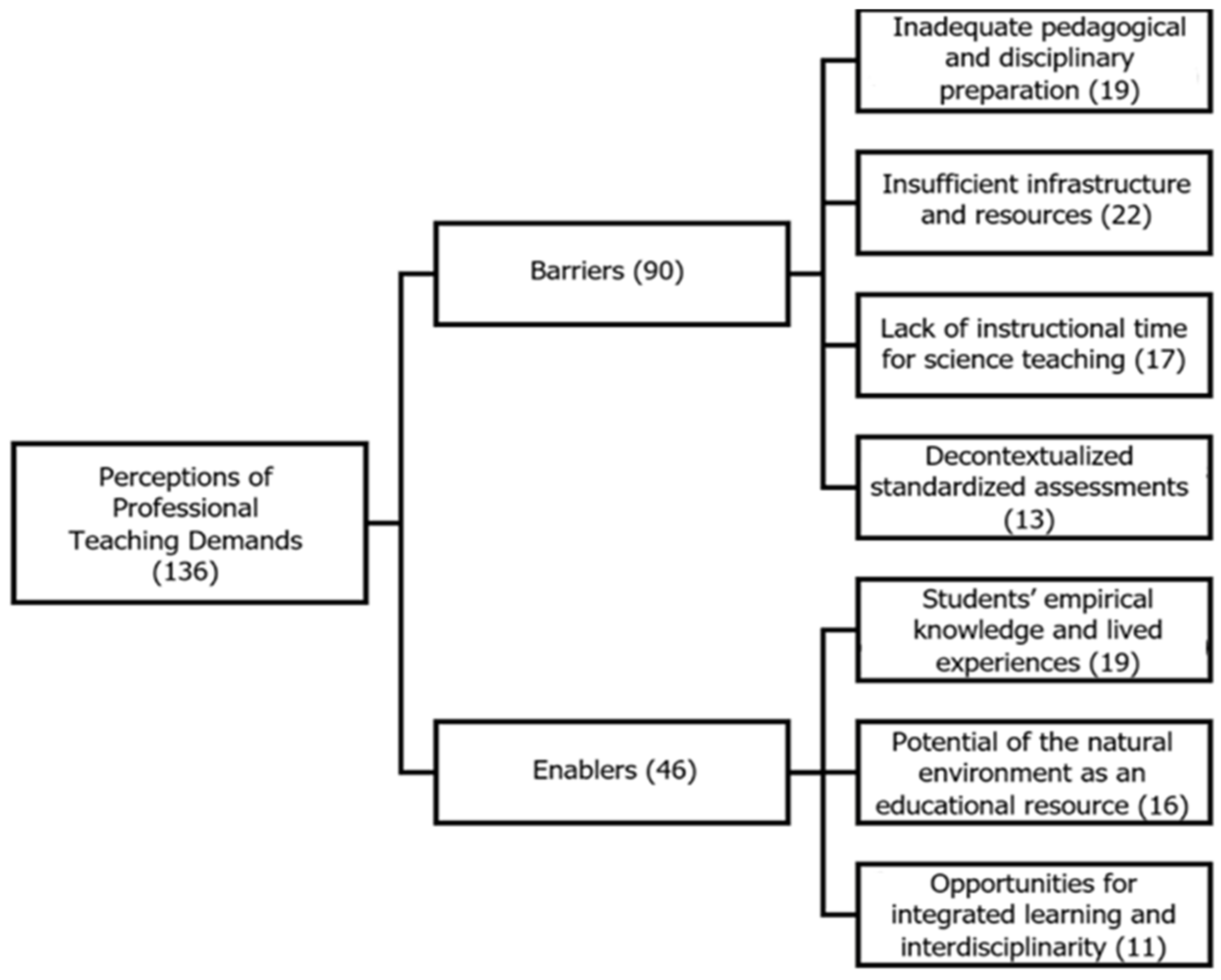

3. Results

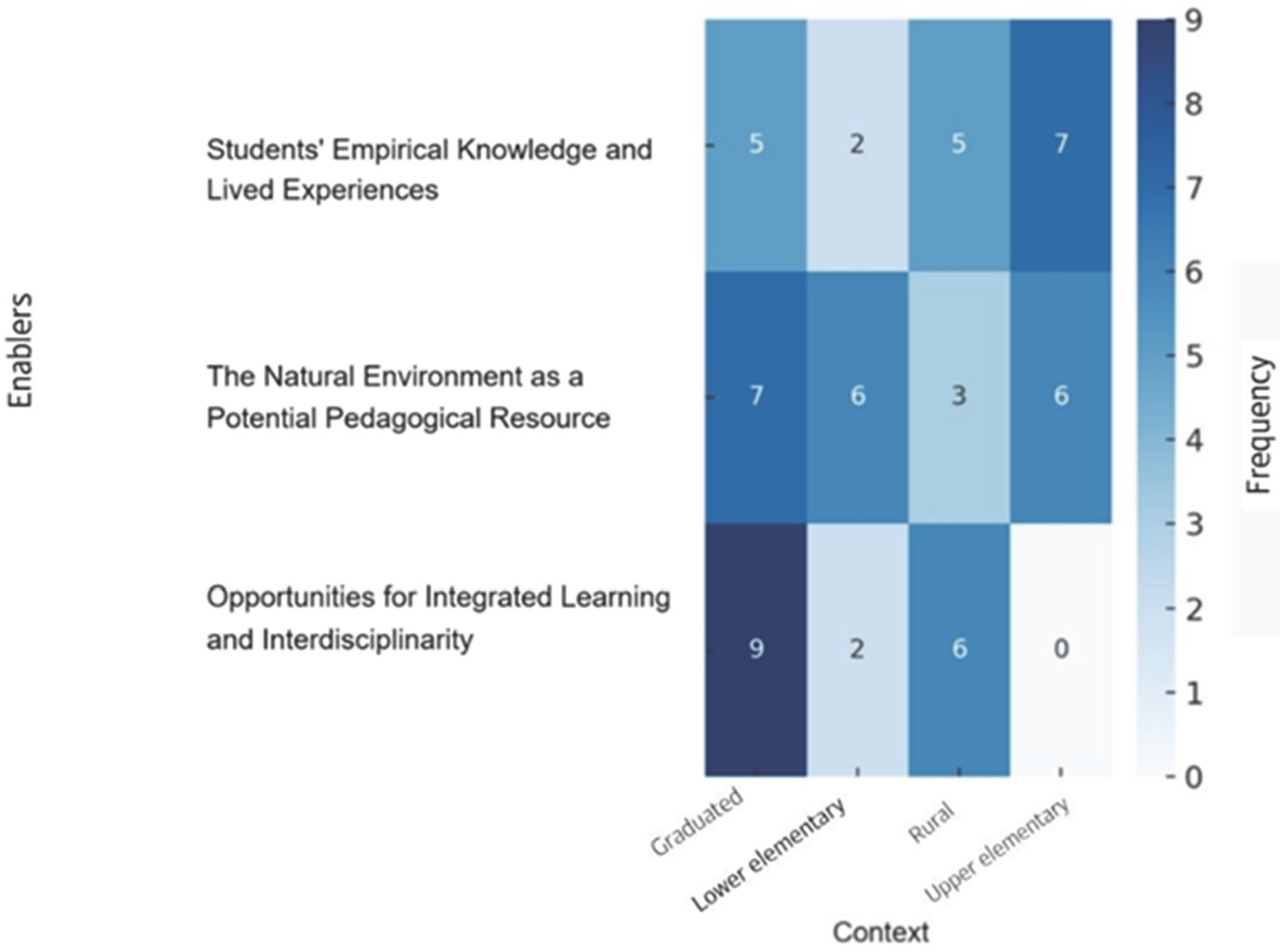

3.1. Enablers

3.1.1. Students’ Empirical Knowledge and Lived Experiences

“I have students from different ethnic backgrounds […] they allow me to explore philosophical comparisons, such as deities we refer to as Mother Earth, or Pachamama.”(34 years old, 10 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

“One of the foundational aspects of our school is the interculturalism lived within the classroom. […] We approach it interdisciplinarity, including science, to address students’ prior knowledge […] even linked to their migratory journeys.”(38 years old, 13 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

“Students’ prior knowledge, their environment, their biodiversity, enriches the classroom. […] Having them share their experiences with peers is also important, along with the context we are in.”(40 years old, 11 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

3.1.2. The Natural Environment as a Potential Pedagogical Resource

“The region offers many opportunities for science development. […] In lower elementary levels, units such as living things and habitats allow for studying various phenomena.”(36 years old, 12 years of teaching experience, lower elementary, public school)

“The region’s characteristics are excellent for science teaching. […] We can go to the Azapa Museum, the Sea Museum. […] Everything is accessible for children to experience science in their own context. […] I’m currently working on a project about native flowers and colors of Arica city.”(37 years old, 5 years of teaching experience, recent graduate, subsidized school)

“The water cycle begins at the coast and ends in the inland villages. […] In the border context, this helps me a lot when teaching science. […] Often, discussions arise because one student says, ‘I’ve never seen rain,’ and another responds, ‘Yes, but rain is like this,’ and through that, they build their own understanding.”(52 years old, 14 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

“We have the advantage of a beautiful sky. […] Recently, I brought in a telescope, and we created a guide so that students could, on their own, say, ‘Are classes over? Let’s grab the telescope […] as the teacher’s manual says.’ […] So they play but also learn outside the classroom.”(26 years old, 1 year of teaching experience, rural, public school)

3.1.3. Opportunities for Integrated Learning and Interdisciplinarity

“We work in an integrated way. If we’re studying living things, we explore the environment. […] We start in the school garden. Since we integrate all subjects, we have more time. In math, for example, students counted in sequence while planting seeds.”(55 years old, 13 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

“In language as well. A girl grabbed a bottle and added stones: ‘This is called an espanta jar” […] We created an illustrated glossary with terms used in planting. That’s how we integrated the subject, and the school coordinator supports this kind of work in the garden.”(42 years of teaching experience, rural, public school)

“I tend to integrate a lot, in order to meet the needs of science using other subjects, such as art or technology. These help me construct the models required in the Natural Sciences curriculum, like the Earth’s layers or habitats in different urban contexts”.(40 years old, 11 years of teaching experience, upper elementary, public school)

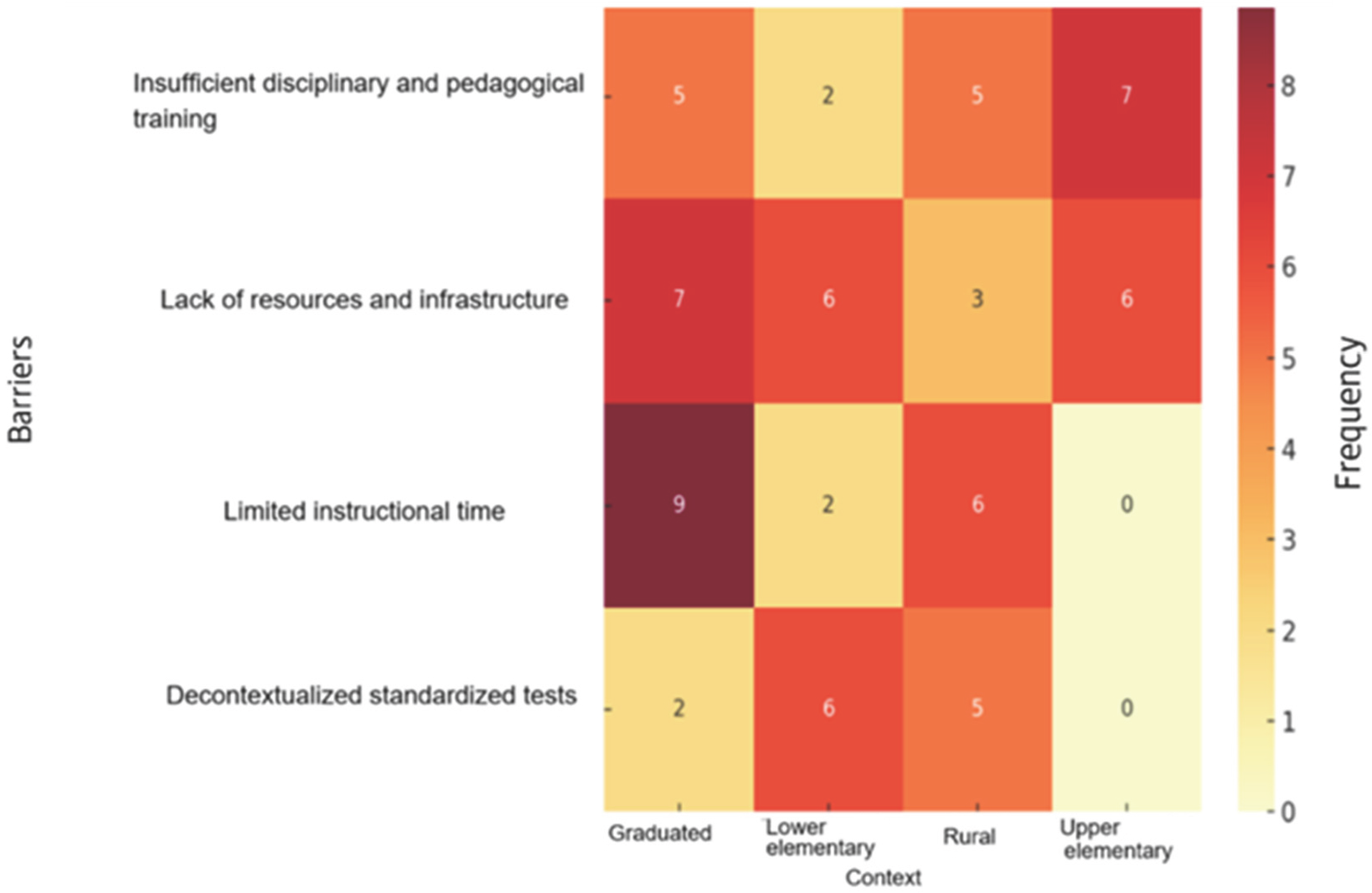

3.2. Challenges

3.2.1. Inadequate Pedagogical and Disciplinary Preparation Among In-Service Teachers

“I think we’re still behind. When we went to university, they taught us science […] but not teaching strategies. I feel like […] we all left very unprepared, and what little science knowledge we have […] we’ve learned by our own.”.(62 years old, 22 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“I think my weakness is disciplinary knowledge, which I’ve had to learn independently. I’ve gone directly to the source […] textbooks […] to study and apply them in a way that’s understandable for children.”(35 years old, 11 years’ experience, lower elementary, public school)

“What bothers me is not having all the skills! Because I wasn’t trained in science. So, I rely a lot on the official Ministry’s textbooks […] and I try to make a connection with language […] but I lack the tools.”(36 years old, 12 years’ experience, lower elementary, public school)

3.2.2. Inadequate Infrastructure and Lack of Resources

“My school can’t take students anywhere. We have 45 students per class. In the school, we only have two trees. We can’t even go outside to look at them.”(37 years old, 5 years’ experience, recent graduate, subsidized school)

“I teach science in a normal classroom with no lab materials at all […] no test tubes, no dyes […], no scales, none of the essential instruments for some science units.”(38 years old, 2 years’ experience, recent graduate, public school)

“There are forgotten areas in schools […] the science lab disappeared during the pandemic. […] This semester we’re just now reopening the science room […] because we lack space and the school lacks adequate structure.”(24 years old, 2 years’ experience, recent graduate, public school)

“Due to time and student numbers, I teach two grades in one room: first grade with 20 kids and second grade with 15. Classrooms are small, we have no lab, and the internet is poor.”(72 years old, 42 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“In the highland areas, there are very few children and absolutely no resources. […] In the multigrade school there’s no lab, nothing. So, the teacher has to be inventive to teach science with whatever they can find.”(26 years old, 1 year experience, rural, public school)

3.2.3. Insufficient Instructional Time for Science

“There are huge gaps in students’ science education. […] Science hours always get reduced in the curriculum.”(51 years old, 17 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“My school offers very little time to science, two hours a week in lower elementary. […] We used to have three hours and covered the curriculum; now we don’t even reach 50% due to other activities or holidays.”(51 years old, 16 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“The Local Education Service decided to regularize flexible hours. […] They cut science hours in all lower elementary, and in upper elementary, there are only three hours from grades 5 to 8. […] That’s made it hard to cover all the learning objectives and skills.”(55 years old, 13 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“Very few hours are aimed to work in rural areas, especially because there is also a focus on Aymara language. […] That’s where they cut science hours. […] Here in the semi-rural zone, we have five hours.”(52 years old, 14 years’ experience, rural, public school)

“There’s no way to teach all that content in the time they expect […] but I have to do it because it will be tested. […] Then we get a chart showing the school scored zero in Life Sciences. See what I mean?”(60 years old, 20 years’ experience, rural, public school)

3.2.4. Decontextualized Standardized Assessments

“I’m in a debate because they’re trying to take away two of my four weekly science hours for SIMCE math prep. […] I don’t want to give them up, I need them, on top of all the extracurricular activities.”(40 years old, 11 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

“Standardized tests like the DIA require students to know the entire curriculum while we’re still on unit one or two. […] They don’t reflect school realities. […] Next year it’s SIMCE for History, the year after for science, and that’s how schools get labeled.”(44 years old, 14 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

“In practice, there are contents you have to teach because of the DIA or another standardized test. […] In March there’s the diagnostic, in July the midterm, and at year’s end the final one. […] That comes straight from the Ministry with the required content that as a teacher you should teacher.”(46 years old, 16 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

“There’s no rural version of the DIA. It’s a national level test, from Arica to Punta Arenas. […] All schools have to cover the same content. […] In science, language doesn’t matter because it’s so specific.”(43 years old, 15 years’ experience, upper elementary, public school)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agencia de Calidad de la Educación [ACE]. (2019). Simce. Available online: https://www.agenciaeducacion.cl/simce/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Aikenhead, G. S. (2001). Students’ ease in crossing cultural borders into school science. Science Education, 85(2), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaslan, M. M., & Damlı, N. (2022). Relations of in-service teacher job motivation with demographic variables. Online Science Education Journal, 7(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ávalos, B., & Aylwin, P. (2007). How young teachers experience their professional work in Chile. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, G. C. S., & El-Hani, C. N. (2009). The contribution of ethnobiology to the construction of a dialogue between ways of knowing: A case study in a Brazilian public high school. Science and Education, 18(3), 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolli, E., Nascimento, W. E., de Oliveira Maia, J., & Villani, A. (2019). Desarrollo profesional de profesores de ciencias: Dimensiones de análisis. Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 18(1), 137–197. [Google Scholar]

- Bastías-Bastías, L. S., & Iturra-Herrera, C. (2022). La formación inicial docente en Chile: Una revisión bibliográfica sobre su implementación y logros. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R. K. (2013). Science instructional time is declining in elementary schools: What are the implications for student achievement and closing the gap? Science Education, 97(6), 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H., Whitcomb, J., & Byrnes, K. (2008). Genres of research in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 1017–1045). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D. B., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Rockoff, J. E., & Wyckoff, J. (2008). The narrowing gap in New York City teacher qualifications and its implications for student achievement in high-poverty schools. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K., Reid, I., & Boyes, L. C. (2006). Teachers as mediators between educational policy and practice. Educational Studies, 32(4), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, S., Ohl, U., & Schulz, J. (2022). Inquiry-based learning on climate change in upper secondary education: A design-based approach. Sustainability, 14(6), 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets, T., Silva, M., & Larrosa, P. (2016). Reflexiones sobre el aprendizaje de las ciencias naturales: Nuevas aproximaciones y desafíos. Estudios Pedagógicos, 42(especial), 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, V., Hochschild, H., & Medeiros, M. P. (2019). Los desafíos pendientes en la ejecución de la nueva política docente: ¿es suficiente con la ley? In A. Carrasco, & L. M. Flores (Eds.), De la reforma a la transformación. Capacidades, innovaciones y regulaciones de la educación chilena. Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Canabal García, C., Campos, M. C. N., & García, L. M. (2017). La reflexión dialógica en la formación inicial del profesorado: Construyendo un marco conceptual. Perspectiva Educacional, 56(2), 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, T. (2011). La investigación sobre formación docente en Chile: Territorios explorados e inexplorados. Calidad en la Educación, 1(35), 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleophas, M. D. G., & Francisco, W. (2018). Metacognição e o ensino e aprendizagem das ciências: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura (RSL). Amazônia, 14(29), 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofré, H., Camacho, J., Galaz, A., Jiménez, J., Santibáñez, D., & Vergara, C. (2010). La educación científica en Chile: Debilidades de la enseñanza y futuros desafíos de la educación de profesores de ciencia. Estudios Pedagógicos, 36(2), 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED]. (2021). Informe de tendencias de la matrícula de pregrado en la educación superior. Consejo Nacional de Educación [CNED]. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, I., & Hirmas, C. (2016). Experiencias de innovación educativa en la formación práctica de carreras de pedagogía en Chile. Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Córtez, M., & Montecinos, C. (2016). Transitando desde la observación a la acción pedagógica en la práctica inicial: Aprender a enseñar con foco en el aprendizaje del alumnado. Estudios Pedagógicos, 42(4), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPEIP. (2017). Estándares pedagógicos y disciplinarios para la formación inicial docente. Versión preliminar. Centro de Perfeccionamiento, Experimentación e Investigaciones Pedagógicas, CPEIP. Área de Formación Inicial de Educadoras y Docentes. Ministerio de Educación.

- Declaración de Budapest. (1999). Declaración sobre la ciencia y el uso del saber científico y programa en pro de la ciencia: Marco general de acción. Unesco. [Google Scholar]

- De Pro Bueno, A. J., De Pro Chereguini, C., & Doménech, J. L. (2022). Cinco problemas en la formación de maestros y maestras para enseñar ciencias en Educación Primaria. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 97(36), 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Lacy, S. L., & Guirguis, R. (2017). Challenges for new teachers and ways of coping with them. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(3), 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Larenas, C. H., Solar Rodríguez, M. I., Soto Hernández, V., & Conejeros Del Solar, M. (2015). Formación docente en Chile: Percepciones de profesores del sistema escolar y docentes universitarios. Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 15(28), 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hani, C., & Mortimer, E. (2007). Multicultural education, pragmatism, and the goals of science teaching. Cultural Study of Science Education, 2, 657–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elige Educar. (2021). Déficit docente en Chile: Actualización 2021. Elige Educar. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada, D., Villena, A., Catriquir, D., Pozo, G., Turra, O., Schilling, C., & Del Pino, M. (2014). Investigación dialógica- kishu kimkelay ta Che en educación. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 13(26), 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada, D., Villena, A., & Del Pino, M. (2018). ¿Hay que formar a los docentes en políticas educativas? Cadernos De Pesquisa, 48(167), 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H. E., Boone, W. J., & Neumann, K. (2023). Quantitative research designs and approaches. In N. G. Lederman, D. L. Zeidler, & J. S. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (Vol. 3, pp. 28–59). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. (2012). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa (T. del Amo, Trans.). Ediciones Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Kanter, P. E., & Medrano, L. A. (2019). Núcleo básico en el análisis de datos cualitativos: Pasos, técnicas de identificación de temas y formas de presentación de resultados. Interdisciplinaria, 36(2), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Contreras, P. A., Llanquín-Yaupi, G. N., Neira-Toledo, V. E., Queupumil-Huaiquinao, E. N., Riquelme-Hueichaleo, L. A., & Arias-Ortega, K. (2021). Prácticas pedagógicas en aula multigrado: Principales desafíos socioeducativos en chile. Cadernos De Pesquisa, 51, e07046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, A., Gómez, V., & Cascopé, M. (2016). ¿Qué le piden los profesores a la formación inicial docente en Chile? Temas De La Agenda Pública, 11(86), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Garay Aguilar, M., & Sillar Velásquez, M. (2018). Evaluación sobre los procesos formativos de los docentes de la región de Magallanes (Chile). Sophia Austral, 1(21), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Weil, C., Cortez Muñoz, M., Pérez Flores, J. L., Bravo González, P., & Ibaceta Guerra, Y. (2013). Construyendo dominios de encuentro para problematizar acerca de las prácticas pedagógicas de profesores secundarios de Ciencias: Incorporando el modelo de Investigación-Acción como plan de formación continua. Estudios Pedagógicos, 39(2), 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez Chaparro, S., & Sepúlveda, R. (2022). Inclusión de estudiantes migrantes en una escuela chilena: Desafíos para las prácticas del liderazgo escolar. Psicoperspectivas, 21(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honingh, M., Ruiter, M., & Van Thiel, S. (2020). Are school boards and educational quality related? Results of an international literature review. Educational Review, 72(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturralde, M., Mariel Bravo, B., & Flores, A. (2017). Agenda actual en investigación en didáctica de las Ciencias Naturales en América Latina y el Caribe. Revista Electrónica De Investigación Educativa, 19(3), 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kelly, G. J. (2023). Qualitative research as culture and practice. In N. G. Lederman, D. L. Zeidler, & J. S. Lederman (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (Vol. III, pp. 60–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Kleickmann, T., Tröbst, S., Jonen, A., Vehmeyer, J., & Möller, K. (2016). The effects of expert scaffolding in elementary science professional development on teachers’ beliefs and motivations, instructional practices, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Cano, M. L., Parra-Bernal, L. R., Burgos-Laitón, S. B., & Gutiérrez-Giraldo, M. M. (2019). La práctica reflexiva del profesor y la relación con el desarrollo profesional en el contexto de la educación superior. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 15(1), 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzabal Blancafort, A., & Merino Rubilar, C. (2021). Investigación en educación científica en Chile: ¿Dónde estamos y hacia dónde vamos? Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, J., & Cáceres, P. (2017). Construcción de concepciones epistemológicas y pedagógicas en profesores secundarios de ciencia. Enseñanza de las ciencias: Revista de investigación y experiencias didácticas, (N° Extra 0), 2781–2786. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación [MINEDUC]. (2021). Marco para la Buena Enseñanza. MINEDUC.

- Ministerio de Educación [MINEDUC]. (2023). Plan de reactivación educativa 2023. MINEDUC.

- Mondaca Rojas, C. E. (2018). Educación y migración transfronteriza en el norte de Chile: Procesos de inclusión y exclusión de estudiantes migrantes peruanos y bolivianos en las escuelas de la región de Arica y Parinacota [Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. [Google Scholar]

- Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico [OECD]. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Vol. I). OECD EBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico [OECD]. (2023). PISA 2025 science framework (Second draft). OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ortúzar, M. S., Flores, C., Milesi, C., & Cox, C. (2009). Aspectos de la formación inicial docente y su influencia en el rendimiento académico de los alumnos. In Camino al Bicentenario: Propuestas para Chile (pp. 155–186). Centro de Políticas Públicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilla, M., & Adúriz-Bravo, A. (2022). Enseñanza de las ciencias para una nueva cultura docente: Desafíos y oportunidades. Ediciones UC. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga-Lobos, M., Arredondo-González, E., Cafena, D., & Merino-Rubilar, C. (2014). Desarrollo de competencias científicas en las primeras edades: El Explora Conicyt de Chile. Educación y Educadores, 17(2), 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffinelli, A. (2013). La calidad de la formación inicial docente en Chile: La perspectiva de los profesores principiantes. Calidad en la Educación, (39), 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educacion. Fundamentos y tradiciones. McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Espinosa, E., & Norambuena Carrasco, C. (2019). Formación inicial docente y espacios fronterizos. Profesores en aulas culturalmente diversas. Región de Arica y Parinacota. Estudios Pedagógicos, 45(2), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Hernández, V., & Díaz Larenas, C. H. (2018). Formación inicial docente en una universidad. Praxis & Saber, 9(20), 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022). Educación en América Latina y el Caribe en el segundo año de la COVID-19. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, A. A., & Sepúlveda, P. Z. (2020). Niñez aymara a ojos de quienes les educan: Percepciones sobre multiculturalidad en escuelas de Arica, Chile. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 25(13), 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, L. (2021). Scientific literacy and social transformation. Science & Education, 30(3), 557–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez Semper, F. (2022). La interculturalidad en las aulas de ciencias en Chile: Prácticas y perspectivas de profesores de ciencias naturales y biología. Universidade do Minho. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/77426 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Amount Teacher | Pre-Service Teacher Education | Average Age | Average Teacher Experience | Type of Establishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEL | 4 | EST | 41.5 | 13.75 | PS |

| RG | 4 | EST | 32.0 | 3.25 | PS/SPS |

| RU | 7 | EST | 52.4 | 17.6 | PS |

| UP | 6 | EST/BST | 40.8 | 13.2 | PS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acosta-García, K.; Valdivia, E.; Jiménez, J.; Dueñas-Zorrilla, M.; Mondaca, C.; Alfaro-Contreras, C. Situated Science Education and Curricular Justice in Rural Borderland Schools: Elementary Teachers’ Voices from Northern Chile. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121656

Acosta-García K, Valdivia E, Jiménez J, Dueñas-Zorrilla M, Mondaca C, Alfaro-Contreras C. Situated Science Education and Curricular Justice in Rural Borderland Schools: Elementary Teachers’ Voices from Northern Chile. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121656

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcosta-García, Katherine, Eduardo Valdivia, Juan Jiménez, Mario Dueñas-Zorrilla, Carlos Mondaca, and Carmen Alfaro-Contreras. 2025. "Situated Science Education and Curricular Justice in Rural Borderland Schools: Elementary Teachers’ Voices from Northern Chile" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121656

APA StyleAcosta-García, K., Valdivia, E., Jiménez, J., Dueñas-Zorrilla, M., Mondaca, C., & Alfaro-Contreras, C. (2025). Situated Science Education and Curricular Justice in Rural Borderland Schools: Elementary Teachers’ Voices from Northern Chile. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121656