1. Introduction

Since mathematical communication serves as a means to share information and is an important part of reasoning, explaining, and solving problems (

Guerreiro, 2008), it is essential for students to learn, explain, and deepen their understanding of arithmetic concepts. Its core element is the ability to articulate mathematical ideas, both orally and in written form. However, many studies show that students’ mathematical communication skills are limited by the abstractness of mathematical objects, which makes it difficult for many students to interpret them (

Ndia et al., 2020). Consequently, these challenges necessitate that teachers possess both explicit mathematical content knowledge and pedagogical ability (

Canogullari & Isiksal-Bostan, 2024), as well as the ability to translate abstract mathematical objects into more concrete forms (

Bremigan et al., 2011;

de Bivar Weinholtz, 2022;

Wu, 2011).

Those challenges can be addressed by not only focusing on delivering content effectively but also fostering interaction and discourse. Two commonly applied instructional models in mathematics education are problem-based learning (PBL) and direct instruction (DI). According to

Hmelo-Silver (

2004), PBL can foster both knowledge and cognitive processes by engaging students in problem-solving experiences. Through PBL, students are exposed to self-directed learning (SDL), subsequently applying their acquired knowledge to the problem and reflecting on their learning outcomes and the efficacy of the instructional strategies (

Hmelo & Cote, 1996). In particular, students contemplate the problem and identify what they need to learn to achieve a solution. PBL is an educational approach in which knowledge is acquired through guided problem-solving activities. It is an instructional approach that utilizes real-world problems as a context for students to learn and develop critical thinking skills—a framework conceptualized by Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, which highlights the significance of social interaction and scaffolding within the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

In teaching using PBL, students should be able to understand complex mathematical concepts and solve them using diverse strategies. It emphasizes student-centered experiences that are relevant to improving mathematical communication skills. PBL promotes student involvement in authentic problem-solving by encouraging the application of critical and creative thinking. This outcome aligns with research by

Arifin et al. (

2020) and

Arviana et al. (

2018), which highlights improvements in students’ communication skills regarding mathematical concepts after learning using the PBL approach.

While PBL encourages exploration, DI offers a contrasting structure that emphasizes clarity and procedural fluency. Despite being teacher-centered, instruction remains applicable in mathematics education, particularly when presenting ideas or materials that require systematic procedural understanding (

Hermawan et al., 2020;

Muawanah et al., 2022). In DI, teachers deliver systematic and structured explanations (

Al-Makahleh, 2011), allowing each student to grasp the material before progressing to more challenging tasks.

Although the two instructional models offer discrete advantages, their effectiveness may depend on how instruction is tailored to accommodate student diversity. It is widely recognized that a classroom is usually composed of students with diverse needs and backgrounds. Teachers must adapt instructional strategies to align with students’ varying ability levels, thereby promoting equitable comprehension (

Fox & Hoffman, 2011). To address this challenge, differentiated instruction has been identified as a practical approach, providing learning experiences tailored to each student’s level of readiness, personal interests, and preferred learning modalities (

Tomlinson, 2001). Differentiated instruction aligns the instructional content with students’ needs, interests, readiness, and learning styles (

Al-Shehri, 2020;

Sanakulova, 2024). This strategy also enables students with varying learning speeds to receive the appropriate challenges and support (

Santangelo & Tomlinson, 2009). It is essential to note that the differentiated instruction employed in these two learning models offers teachers flexibility to tailor teaching methods to students’ individual needs, enabling all students, regardless of their level of mathematical dispositions, to enhance their mathematical communication skills (

Goyibova et al., 2025). Flexibility refers to the adjustability of how each model is implemented; for instance, the teacher can vary task difficulty, scaffolding, time, and grouping.

PBL integrated with differentiated instruction allows teachers to provide more targeted support to students based on their individual needs (

Kyeremeh et al., 2021;

Pozas et al., 2020;

Smets et al., 2022). It facilitates students’ engagement in authentic problem-solving contexts while offering individualized support (

Morgan, 2014). The students can demonstrate their conceptual understanding and are recognized as an effective learning approach to achieve maximum learning outcomes (

Variacion et al., 2021). Thus, it can enhance students’ mathematical communication skills by involving them in collaboration, idea exploration, and the delivery of outcomes in a relevant and structured manner (

Fitria et al., 2020).

DI integrated with differentiated instruction exposes students to explicit, targeted instruction and to learning flexibility tailored to their individual needs. The instruction commences with verbal explanations accompanied by visual aids, such as graphs, diagrams, or simulations, and it provides exercises tailored to students’ specific needs. Teachers can provide explicit instructions to students about what they should do while also allowing them to work at their own pace. For example, in mathematics teaching, teachers offer the same initial explanation for the entire class, then differentiate the tasks or how students practice the concept based on their abilities.

In addition, students’ mathematical disposition, a combination of motivation, confidence, perseverance, and curiosity toward learning mathematics (

Yaniawati et al., 2019), is also crucial to consider the effectiveness of learning models highly depends on this construct. It profoundly influences how students interact in the learning process. As described in previous research (

Hannula, 2006;

McLeod, 1992), affective components significantly influence how students approach and persist in mathematical tasks. People with a high disposition possess the habits of analyzing, questioning, and reflecting—essential catalysts for accomplishing tasks that require deeper understanding or creative problem-solving. They are open to trying new strategies, making connections, and learning from mistakes, thereby encouraging them to take on demanding tasks and persevere despite obstacles. Ultimately, it affects their learning outcomes. As found by

Kusmaryono et al. (

2019), there is a significant effect of mathematical disposition on mathematical power ability.

Although prior studies have explored the individual impact of PBL on mathematics achievement (

Abdullah et al., 2010;

Ahmad et al., 2024;

Ajai et al., 2013;

Boye & Agyei, 2023;

Nufus & Mursalin, 2020) and mathematical disposition on achievement (

Kamid et al., 2021;

Kusmaryono et al., 2019;

Wahyudin et al., 2024;

Yaniawati et al., 2019), few studies have examined the joint effect of instructional models and learner disposition on mathematical communication skills, particularly within the context of differentiated instruction. Most existing research has generally focused on the efficiency of PBL or DI in isolation without considering how student-level characteristics interact with pedagogical design. This study addresses the identified gap by investigating the interactions between instructional models, namely PBL integrated with differentiated instruction, and DI integrated with differentiated instruction, and the influence of students’ mathematical dispositions on their mathematical communication skills. Integrating differentiated instruction into both models is expected to improve the learning experience for students at all disposition levels.

This study addresses the following research questions:

How do learning models (PBL vs. DI) affect students’ mathematical communication skills?

How do students’ mathematical dispositions (high vs. low) affect their communication skills?

How is the interaction between learning models and mathematical disposition influencing students’ mathematical communication skills?

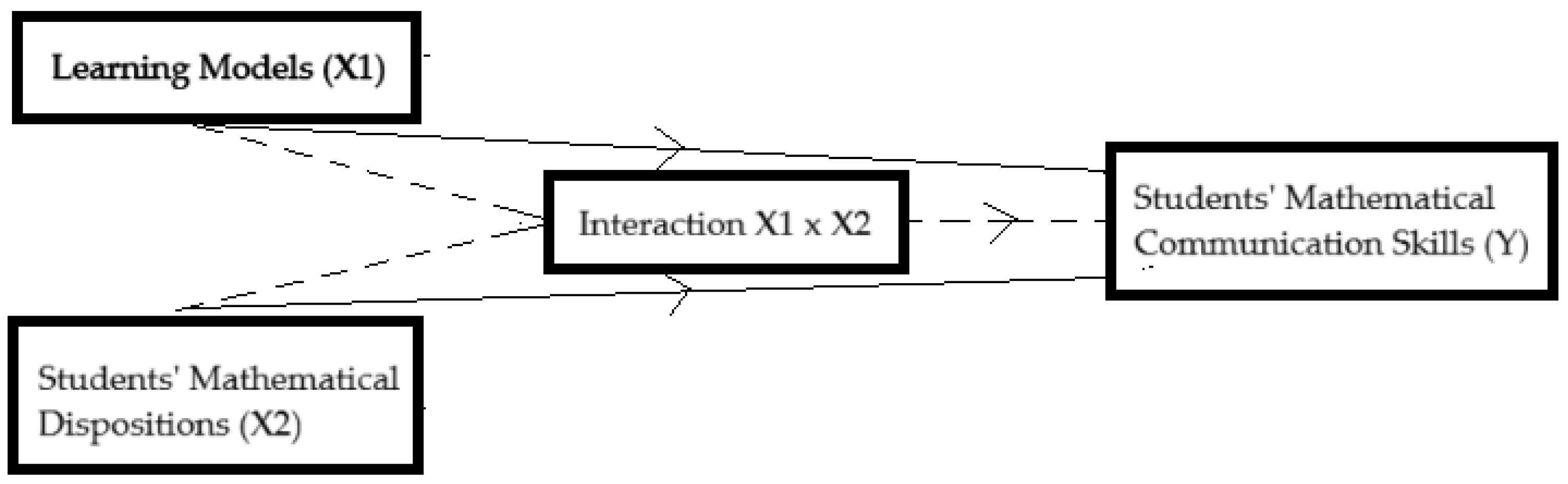

The following figure illustrates the relationship among the variables being investigated.

Figure 1 illustrates how learning models (X1) and mathematical dispositions (X2) interact to influence mathematical communication skills (Y). It displays the relationship of the research questions being investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

This research employed a quasi-experimental research design with a 2 × 2 factorial structure, as presented in

Table 1. The 2 × 2 factorial design was chosen to examine both the main and interaction effects of instructional models and mathematical disposition on students’ mathematical communication. This approach enables a deeper understanding of how mathematical disposition impacts instructional effectiveness.

The study population consisted of all grade XI students of SMA 4 Kendari registered in the even semester of the 2024/2025 academic year, totaling 571 students divided into 16 parallel classes. There were 36 students from Class XII and 39 students from Class XIJ selected as samples using a simple random sampling technique. Students in class XII were taught using the PBL, and those in class XIJ were taught using DI. Both models integrated differentiated instruction.

This study employed two instruments to assess students’ mathematical disposition and mathematical communication skills. First, the researchers developed a brief performance-based test on mathematical communication skills. It consisted of five items based on indicators of mathematical communication skills, such as written explanations, visual representations (e.g., drawings), and mathematical expressions. Two items targeted written explanation, two items targeted visual representation, and one item required integrating symbols with a brief explanation. Thus, the tasks were designed to target different mathematical skills, which aimed to demonstrate how students are reasoning through the mathematical concepts. For example, students were asked to explain their thought process in writing, which allowed the assessment of the clarity and accuracy of their reasoning. Items were written based on the lesson objectives. The mathematics topic taught in both classes was statistics. In this unit, the mathematical communication skills developed were (1) expressing a given set of data in mathematical form to facilitate analysis, (2) visually representing the dataset, and (3) providing a written explanation of the procedures and reasoning used in the data analysis. The test was administered twice, namely prior to teaching and after teaching. The test underwent content validation by a panel of five subject-matter experts and achieved a reliability coefficient of 0.86.

Second, mathematical disposition was assessed using a 39-item Likert-scale questionnaire. It has seven dimensions, each of which were assessed through specific items within the questionnaire such as self-confidence (six items: number 1, 2, 4, 13, 20, and 24), flexibility (six items: number 5, 6, 8, 9, 12, and 22), persistence (seven items: number 11, 14, 15, 17, 21, 29, and 38), curiosity (six items: 3, 16, 18, 25, 26, and 28), metacognitive awareness (six items: number 7, 10, 19, 30, 31, and 33), evaluation (four items: number 34, 35, 36, and 37) and appreciation for mathematics in real-life contexts (four items: number 23, 27, 32, and 39). The instrument demonstrated strong internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78. Students were categorized into high- and low-disposition groups using a median split of the total disposition scores.

To collect the data, first, data on mathematical disposition were collected by administering a questionnaire to two groups of students identified as samples, prior to the learning process, using the PBL and direct instruction models, both of which used differentiated instruction.

Table 2 compares the learning activities in the two instructional models. The learning process was conducted in the two selected sample classrooms according to the established steps: one class was instructed using the PBL (A1) with differentiated instruction, while the other class received DI (A2) with the same differentiated instruction.

Following the five instructional sessions, an evaluation was conducted at the sixth meeting to gauge students’ mathematical communication abilities. The assessment comprised five questions prepared by the researchers, based on the indicators of mathematical communication skills derived from the content covered in the preceding five sessions.

The data analysis technique employed descriptive statistics and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the interaction effects of the instructional models and mathematical disposition on communication outcomes. Normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions were tested prior to conducting ANOVA. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that students taught with PBL, implemented through differentiated instruction, had considerably higher mathematical communication skills compared to DI. It contributes to the existing literature on instructional design by highlighting the pedagogical effectiveness of integrating differentiated instruction. The results imply that teaching methods that cater to the students’ individual needs and address their unique differences can significantly enhance mathematical communication skills. For instance, previous studies (

Arifin et al., 2020;

Arviana et al., 2018) have found that differentiated PBL helped students think critically, while in their meta-analysis study,

Wijnia et al. (

2024) discovered that differentiated PBL helped students stay motivated in classrooms. The effect sizes were greater when problem-driven learning was implemented in an individual course than when using a curriculum-wide approach, especially in science subjects, such as healthcare and STEM.

PBL with differentiated instruction aims to enhance students’ ability to explain mathematical ideas, use appropriate representations, and logically discuss and solve mathematical problems through a holistic approach to developing students’ mathematical skills, particularly in terms of communication and problem-solving (

Rézio et al., 2022). Providing relevant challenges and adjusting the learning model to specific strategies that meet students’ needs are means of creating an inclusive learning environment and supporting the development of deep mathematical abilities. The PBL model with differentiated instruction demonstrated greater effectiveness in enhancing mathematical communication skills as students had the opportunity to independently explore problems, engage in peer discussions, and communicate their ideas more effectively.

One component of PBL is distributed cognition, which enables the social sharing of the information-gathering workload, thereby decreasing the cognitive load of any one individual (

Schmidt et al., 2007). Moreover, the effectiveness of PBL is attributable to its nature of social interaction, where students’ perspectives interact rather than being presented in isolation; new ideas emerge and challenge existing concepts, leading to a potential transformation of knowledge (

Innes, 2006). It aligns with Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and constructivist learning frameworks, which highlight social interaction, contextual learning, and scaffolded experiences as part of the process of knowledge formation. PBL inherently fosters these qualities by involving students in collaborative activities that require critical thinking, problem-solving, and the synthesis of interdisciplinary knowledge. When combined with differentiated instruction—where tasks, content, and assessments are customized to align with student readiness, interests, and learning profiles—PBL fosters a flexible, student-centered educational environment that seems to significantly promote cognitive and emotional development. Another study (

Pease & Kuhn, 2011) found that the practical component of PBL appears to be the focus on engagement with a problem.

Conversely, for DI, despite its recognition for clarity, efficiency, and efficacy in imparting core knowledge—especially during the initial phases of material delivery—it may lack responsiveness to individual learning differences and be less effective at fostering higher-order thinking skills. It prioritizes uniformity and instructor authority, potentially limiting students’ ability to engage in self-directed inquiry and apply their knowledge in complex, real-world situations. Consequently, students subjected to differentiated teaching may receive structured support. Still, they may exhibit diminished engagement or motivation, particularly when instruction fails to align with their learning preferences or developmental needs.

Regarding mathematical disposition, this study found that students with a high level of mathematical disposition also have higher mathematical communication skills, as evidenced by their mean scores. In other words, students with more favourable mathematical dispositions tend to have higher scores in communicating mathematical ideas, reasoning, and arguments in both spoken and written forms. These results are in line with other research indicating that the affective domain is an important factor in how well people learn arithmetic (

Hannula, 2006;

McLeod, 1992).

As illustrated in

Table 6, students with high mathematical disposition taught using the PBL model integrated with differentiated instruction (A1B1) exhibited much better results compared to those taught with the DI integrated with differentiated instruction (A2B1). The mean score of mathematical communication skills in the A1B1 group was 88.14, while that of the A2B1 group was 63.19. This finding is similar to the results of another study (

Setiawan & Surahmat, 2023), which found that mathematical disposition has a significant effect on students’ mathematics learning outcomes.

Moreover, mathematical disposition is related to the attitude–behavior–cognition framework. Students with a pleasant mood and high disposition are more likely to engage in sustained mathematical problem-solving, thereby improving their communication skills. Disposition is not only about a result of learning, but also a mediator to navigate challenging times, devise strategies, and reflect on their reasoning (

Carr & Claxton, 2002), which are highly necessary for practical mathematical communication skills (

Minarti & Wahyudin, 2019;

Octaviani et al., 2023;

Wahyuni et al., 2023;

Yaniawati et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the primary finding of this study is the significant interaction between the instructional models and mathematical disposition (

Table 5). The interaction effect was significant (F = 31.97, ≥F

table 4.08, α = 0.05), indicating that the effectiveness of instructional models in enhancing mathematical communication depends on students’ levels of mathematical disposition. It implies that the learning models applied—both PBL and DI- have different and significant effects depending on students’ mathematical dispositions. In other words, high or low mathematical dispositions affect the effectiveness of each learning model in improving mathematical communication skills. This finding supports the hypothesis that the success of the instructional model for mathematical communication skills depends on students’ individual characteristics, such as mathematical dispositions (

Guerreiro, 2008). Prior work suggests complementary strengths of PBL (richer explanations and representations) and DI (efficient foundational skill-building), while student beliefs, interests, and confidence shape willingness to communicate mathematically. Our findings extend this literature by showing that who benefits most from each model depends not only on the model itself but also on disposition. (

Hwang & Choi, 2020) found that the achievement gap in emotional dispositions, such as preferences and aversions, diminished when teachers consistently employed specific instructional strategies, including assigning demanding tasks, allowing students to determine their own problem-solving methods, and encouraging them to articulate their thoughts in class. Students who expressed aversion to mathematics tended to achieve higher results when their instructors employed those tactics more frequently.

The results of this study suggest that students possessing a high level of mathematical disposition are better taught using the PBL integrated with differentiated instruction to improve their mathematical communication skills because it necessitates active involvement and deep cognitive processing, all of which aligns with the characteristics of students with high dispositions (

Kamid et al., 2021;

Thomson & Pampaka, 2021). Students with low dispositions are better taught using DI because it offers explicit structure and guidance aligned with their cognitive needs. It does not require independent involvement and higher critical thinking skills. This result aligns with the view that students with a low level of mathematical disposition need more direct and explicit guidance in learning (

Dina et al., 2019). It underscores the need for highly personalized student profiles in the instructional design.

Additionally, students who excel in mathematical reasoning are more likely to speak up in class, ask questions, explain their reasoning, and collaborate with their classmates. Such activities are commonly found in a classroom that integrates PBL and are believed to facilitate the construction of mathematical meaning, which is crucial for cognitive development, according to Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. So, the mathematical disposition is a predictive affective construct that supports both motivation and the epistemic engagement needed for mathematical communication skills.

The substantial relationship between disposition and instructional model implies that the level of scaffolding needed in addition to the instructional approach influences students’ mathematical communication skills. When given structured support, students with lower mathematical dispositions—who benefit more from DI—may be functioning within their Zone of Proximal Development. This aligns with Vygotsky’s theory that learning is most effective in settings with appropriate scaffolding. Higher-disposition students, on the other hand, may need less structure, enabling more discussion and investigation in PBL, which promotes the collaborative creation of knowledge through social interaction. This relationship between disposition and instruction highlights the importance of tailoring teaching approaches to each student’s unique learning needs and developmental stage.

The significant interaction between instructional models and mathematical disposition validates that one-size-fits-all instructional methods in mathematics education are inadequate. Teacher and curriculum developers should consider students’ affective characteristics, especially their mathematical disposition, prior to establishing teaching methods. Besides, instructional decisions can be enhanced by early diagnosis of student disposition and aligning support accordingly—for instance, structuring PBL with additional scaffolding for students requiring increased confidence.

This study did not involve student characteristics—such as learning motivation, curiosity, or social support—that may correlate with both participation and outcomes. Consequently, some of the reported effects may be attributable to these factors rather than the intervention itself, necessitating cautious interpretation of the results.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that there is a significant interaction between instructional models (A1, A2) and mathematical dispositions (B1, B2) in shaping students’ mathematical communication skills. Students with a high level of disposition taught using PBL (A1B1) have higher mathematical communication skills than their peers who received DI (A2B1). Conversely, students with a low level of disposition performed better under the DI (A2B2) than under PBL (A1B2). In other words, DI is more effective for students with lower levels of mathematical disposition. Overall, the findings suggest that the PBL model with differentiated instruction yielded higher average scores than DI. These findings underscore the importance of aligning instructional practices with students’ dispositional characteristics to improve their mathematical communication skills. This study contributes to the existing literature on adaptive training by emphasizing the moderating influence of mathematical disposition on instructional efficacy.

Based on the findings, it is recommended that teachers consider students’ mathematical disposition to determine the learning model to be used. It can be done by assessing students’ dispositions before teaching and aligning support accordingly—for instance, structuring PBL with additional scaffolding for students who need increased confidence. Moreover, to develop effective learning materials, teachers need to consider differences in students’ mathematical dispositions, so that the learning process can be implemented according to students’ abilities and characteristics. This study was limited by its relatively small sample size and was specific to the context of a public high school in Indonesia, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Further research is needed with larger samples at different levels of education, and combining the PBL and DI integrated with differentiated instruction.

This research does not account for other factors that may influence mathematical communication skills, such as learning motivation, interest, social support from classmates and family, which could impact the internal validity of the conclusions drawn.