Beyond Technology Tools: Supporting Student Engagement in Technology Enhanced Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is student engagement conceptualised in the analysed studies?

- Which technology tools have been empirically shown to support different aspects of student engagement?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Student Engagement

2.2. Technology Enhanced Learning and Student Engagement

3. Methodology and Methods

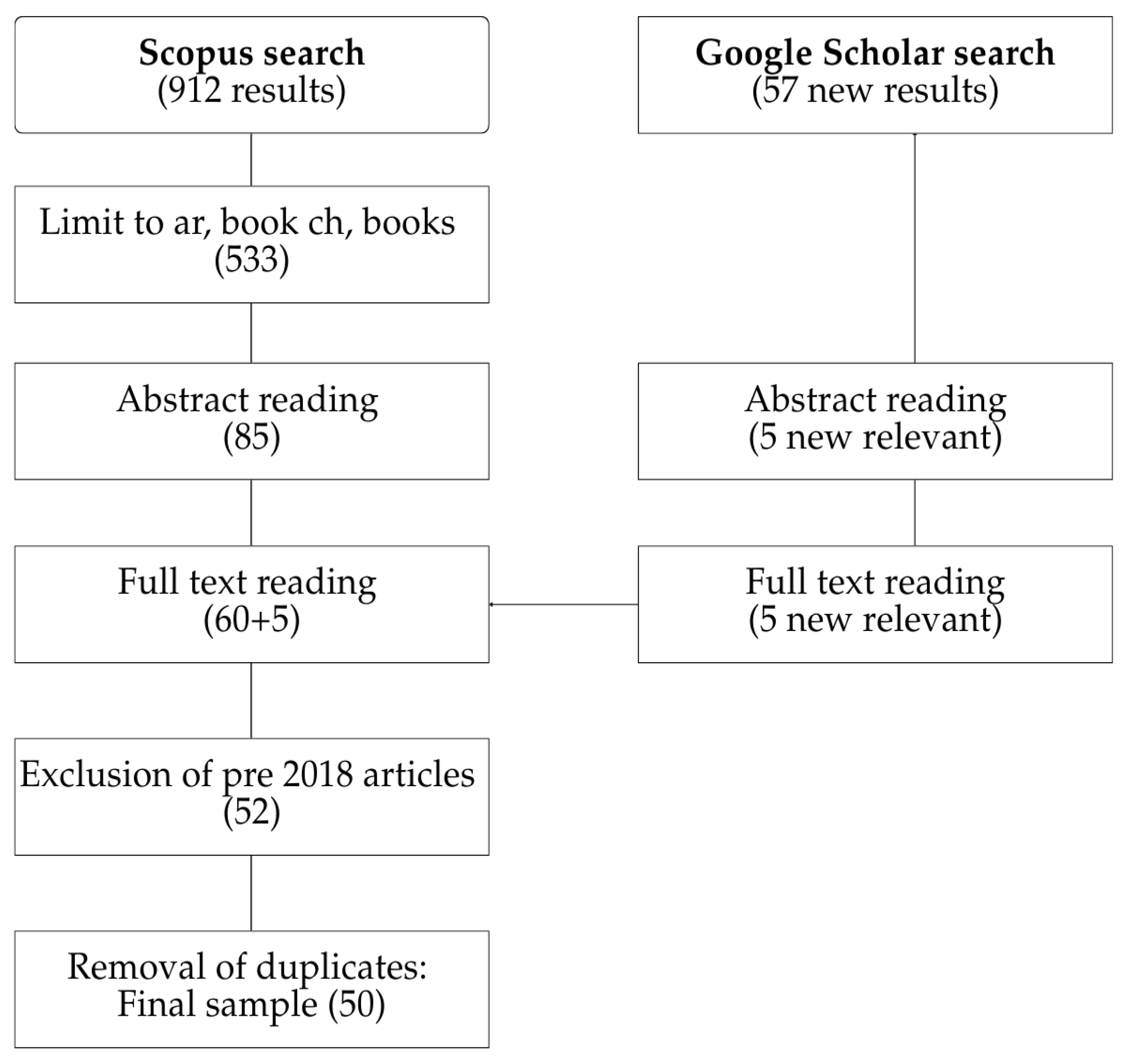

3.1. Searching

3.2. Screening

- Peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and books, written in English.

- Only empirical studies were included.

- Only studies that discuss a specific technology tool and how it affects student engagement were included.

- Studies conducted in the higher education context.

- Studies published between 2015 and 2025 (with further exclusion of studies published before 2018, to extend a critical review by Schindler et al. (2017)).

3.3. Data Analysis

- Conceptualisation or operationalisation of engagement.

- 2.

- Theoretical or analytical framework employed.

- 3.

- Evaluated technology tool.

- 4.

- Application of technology to support student engagement, and examples of how student engagement is supported by technology tools.

4. Results

4.1. Conceptualisation of Student Engagement

4.2. Technology Tools to Support Student Engagement

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEL | Technology-Enhanced Learning |

| HE | Higher Education |

| NSSE | National Survey of Student Engagement |

| AUSSE | Australasian Survey of Student Engagement |

| UKES | United Kingdom Engagement Survey |

| ELI | Engaged Learning Index |

| CoI | Community of Inquiry (framework) |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LMS | Learning Management System |

| FBM | Fogg Behaviour Model |

| ADDIE | Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation |

| AWE | Automated Writing Evaluation |

| ELS | English Language Support |

| CCA | Constant Comparative Analysis |

References

- Ahshan, R. (2021). A framework of implementing strategies for active student engagement in remote/online teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(9), 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfoudari, A. M., Durugbo, C. M., & Aldhmour, F. M. (2021). Understanding socio-technological challenges of smart classrooms using a systematic review. Computers & Education, 173, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hammouri, M. M., & Rababah, J. A. (2025). The effectiveness of the Good Behavior Game on students’ academic engagement in online-based learning. Online Learning, 29(1), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alioon, Y., & Delialioğlu, Ö. (2019). The effect of authentic m-learning activities on student engagement and motivation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(2), 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, N. E., Bigdeli, S., & Mirhosseini, F. M. (2024). Enhancing student engagement in electronic platforms: E-gallery walk. Acta Medica Iranica, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N., Meccawy, M., Samra, H., & El-Sabagh, H. A. (2025). Identifying weekly student engagement patterns in e-learning via k-means clustering and label-based validation. Electronics, 14(15), 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuyahong, B., & Pucharoen, N. (2023). Exploring the effectiveness of mobile learning technologies in enhancing student engagement and learning outcomes. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 18, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayouni, S., Hajjej, F., Maddeh, M., & Al-Otaibi, S. (2021). A new ML-based approach to enhance student engagement in online environment. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0258788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakic, M., Pakala, K., Bairaktarova, D., & Bose, D. (2025). Enhancing engineering education: Investigating the impact of mobile devices on learning in a thermal-fluids course. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 53(3), 631–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balalle, H. (2024). Exploring student engagement in technology-based education in relation to gamification, online/distance learning, and other factors: A systematic literature review. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 9, 100870. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechkoff, J. (2019). Gamification using a choose-your-own-adventure type platform to augment learning and facilitate student engagement in marketing education. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 27(1), 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bergdahl, N., Bond, M., Sjöberg, J., Dougherty, M., & Oxley, E. (2024). Unpacking student engagement in higher education learning analytics: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, N., & Nouri, J. (2020). Student engagement and disengagement in TEL–The role of gaming, gender and non-native students. Research in Learning Technology, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M. (2016). Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learning and Instruction, 43, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M., & Bedenlier, S. (2019). Facilitating student engagement through educational technology: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2019(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M., Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Kerres, M. (2020). Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bote-Lorenzo, M. L., & Gómez-Sánchez, E. (2017, March 13–17). Predicting the decrease of engagement indicators in a MOOC. Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference (pp. 143–147), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchrika, I., Harrati, N., Wanick, V., & Wills, G. (2021). Exploring the impact of gamification on student engagement and involvement with e-learning systems. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(8), 1244–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, R. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development: Executive summary and model. Center for Educational Technology, Florida State University. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2000). Ecological systems theory. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 129–133). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A., Lawrence, J., Axelsen, M., Redmond, P., Turner, J., Maloney, S., & Galligan, L. (2024). The effectiveness of nudging key learning resources to support online engagement in higher education courses. Distance Education, 45(1), 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G. F., Heller, N. A., Burch, J. J., Freed, R., & Steed, S. A. (2015). Student engagement: Developing a conceptual framework and survey instrument. Journal of Education for Business, 90(4), 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K., Fanshawe, M., & Tualaulelei, E. (2022). We can’t always measure what matters: Revealing opportunities to enhance online student engagement through pedagogical care. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K., & Larmar, S. (2020). Acknowledging another face in the virtual crowd: Reimagining the online experience in higher education through an online pedagogy of care. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(5), 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. A., Jirout, J. J., & Bell, B. A. (2025). Understanding cognitive engagement in virtual discussion boards. Active Learning in Higher Education, 26(1), 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J. F. (2006). Scopus database: A review. Biomedical Digital Libraries, 3(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S., & Phongsatha, S. (2025). An empirical study of the AI-driven platform in blended learning for Business English performance and student engagement. Language Testing in Asia, 15(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleman, B. L., & Page, L. C. (2016). Freshman year financial aid nudges: An experiment to increase FAFSA renewal and college persistence. Journal of Human Resources, 51(2), 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R. C., & Yu, Z. S. (2018). Using augmented reality technologies to enhance students’ engagement and achievement in science laboratories. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies (IJDET), 16(4), 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., & Xiao, L. G. (2025). Human–computer interaction in smart classrooms: Enhancing educational outcomes in Chinese higher education. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(22), 14379–14400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Huang, K. (2025). ‘It is useful, but we feel confused and frustrated’: Exploring learner engagement with AWE feedback in collaborative academic writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. S. D., Lambert, A. D., & Guidry, K. R. (2010). Engaging online learners: The impact of web-based learning technology on college student engagement. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, H. (2007). A model of online and general campus-based student engagement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkawski, B. C., & Lyman, E. W. (2016). An instructional design framework for fostering student engagement in online learning environments. TechTrends, 60(6), 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard, M. T., & Nielsen, H. S. (2018). Nudging in education. Economics of Education Review, 64, 313–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results [Doctoral dissertation, MIT Sloan School of Management]. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z., & Xue, W. (2025). Navigating anxiety in digital learning: How AI-driven personalization and emotion recognition shape EFL students’ engagement. Acta Psychologica, 260, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, M. D. (2015). Measuring student engagement in the online course: The online student engagement scale (OSE). Online Learning, 19(4), n4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drljević, N., Botički, I., & Wong, L. H. (2024). Observing student engagement during augmented reality learning in early primary school. Journal of Computers in Education, 11(1), 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit. [Google Scholar]

- Ergün, E., & Usluel, Y. K. (2015). Çevrimiçi öğrenme ortamlarında öğrenci bağlılık ölçeği’nin türkçe uyarlaması: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Eğitim Teknolojisi Kuram ve Uygulama, 5(1), 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanshawe, M., Brown, A., & Redmond, P. (2025). Using an online engagement framework to redesign the learning environment for higher education students: A design experiment approach. Online Learning, 29(2), 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2022). Assistive technology for the inclusion of students with disabilities: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(5), 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M. M., & Baird, D. E. (2020). Humanizing user experience design strategies with NEW technologies: AR, VR, MR, ZOOM, ALLY and AI to support student engagement and retention in higher education. In International perspectives on the role of technology in humanizing higher education (pp. 105–129). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B. J. (2009, April 26–29). A behavior model for persuasive design. 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology (pp. 1–7), Claremont, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fram, S. M. (2013). The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. Qualitative Report, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical thinking in text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. H., & Betts, K. (2020). From discussion forums to eMeetings: Integrating high touch strategies to increase student engagement, academic performance, and retention in large online courses. Online Learning, 24(1), 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getenet, S., & Tualaulelei, E. (2023). Using interactive technologies to enhance student engagement in higher education online learning. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 39(4), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G. (2014, May 1). Student engagement, the latest buzzword. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/student-engagement-the-latest-buzzword/2012947.article (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., & Gijselaers, W. (2013). Investigating the relations between motivation, tool use, participation, and performance in an e-learning course using web-videoconferencing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goi, C. L. (2024). The impact of VR-based learning on student engagement and learning outcomes in higher education. In C. Goi (Ed.), Teaching and learning for a sustainable future: Innovative strategies and best practices (pp. 207–223). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C. C., & Perkins, D. (2019). Utilizing early engagement and machine learning to predict student outcomes. Computers & Education, 131, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, S. (2022). The tensions of student engagement with technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(3), 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Chen, Y., Wang, T., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Online learning resource management system utilization and college students’ engagement at Zhongshan University. International Journal of Web-Based Learning and Teaching Technologies (IJWLTT), 19(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadi, H., Tafili, A., Kates, F. R., Larson, S. A., Ellison, C., & Song, J. (2023). Exploring an innovative approach to enhance discussion board engagement. TechTrends, 67(4), 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelsman, M. M., Briggs, W. L., Sullivan, N., & Towler, A. (2005). A measure of college student course engagement. The Journal of Educational Research, 98(3), 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers & Education, 90, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, H., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M. Y. (2021). Enhancing learning engagement during COVID-19 pandemic: Self-efficacy in time management, technology use, and online learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1640–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisey, F., Zhu, T., & He, Y. (2024). Use of interactive storytelling trailers to engage students in an online learning environment. Active Learning in Higher Education, 25(1), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrey, C. E. (2020). Kahoot! Using a game-based approach to blended learning to support effective learning environments and student engagement in traditional lecture theatres. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 29(2), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, B., Nair, P., Hill-Lindsay, S., & Chukoskie, L. (2022). Engagement in online learning: Student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 7, 851019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. M. (2023). Using educational technologies (Padlet) for student engagement–reflection from the Australian classroom. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 40(5), 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsu, N. J., Adesope, O., & Bayly, D. J. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of audience response systems (clicker-based technologies) on cognition and affect. Computers & Education, 94, 102–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hutain, J., & Michinov, N. (2022). Improving student engagement during in-person classes by using functionalities of a digital learning environment. Computers & Education, 183, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlawi, J. (2021). Students’ engagement in e-learning applications: The impact of sound’s elements. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6227–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, R. (2012). The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Computers & Education, 58(1), 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kahu, E. R., Thomas, H. G., & Heinrich, E. (2024). A sense of community and camaraderie: Increasing student engagement by supplementing an LMS with a Learning Commons Communication Tool. Active Learning in Higher Education, 25(2), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskas, M. (2018). Expression of engagement in gamified study course. Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, (6), 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., & Yilmaz, R. (2022). Learning analytics intervention improves students’ engagement in online learning. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(2), 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, T., Raddats, C., & Qian, L. (2025). Enabling international student engagement through online learning environments. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 62(4), 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearsley, G., & Shneiderman, B. (1998). Engagement theory: A framework for technology-based teaching and learning. Educational Technology, 38(5), 20–23. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44428478.pdf?casa_token=NhT-FeN-7AsAAAAA:t_N-sqI6fegSN2llzOoIiyLIT23wiuuwLX1UiY8RbvTbdqNuO67cVcAmxCSZ0PjdlWCRPRryo_74tiE9k-T2Eb9deTv7SSCg3Gd24LnVWJSKoRA2 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Khanchai, S., Worragin, P., Ariya, P., Intawong, K., & Puritat, K. (2025). Toward sustainable digital literacy: A comparative study of gamified and non-gamified digital board games in higher education. Education Sciences, 15(8), 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, O. Y. (2023). Technophobia: How students’ technophobia impacts their technology acceptance in an online class. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(13), 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. P., Ngoc, T. H. T., Thu, H. N. T., Diem, K. B. T., Thai, A. N. H., & Thuy, L. N. T. (2022). Exploring students’ engagement of using mediating tools in e-learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 17(19), 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, L. (2017). Learning first, technology second: The educator’s guide to designing authentic lessons. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G. D., Cruce, T. M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J., & Gonyea, R. M. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(5), 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, K., & Wall, J. G. (2021). Video-based learning to enhance teaching of practical microbiology. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 368(2), fnaa203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalmas, M., O’Brien, H., & Yom-Tov, E. (2022). Measuring user engagement. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L. T. (2020). A real game-changer in ESL classroom? Boosting Vietnamese learner engagement with gamification. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 21(3), 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X. P., Li, B. B., Yao, Z. N., Yang, Z., & Zhang, M. (2024). The impact of virtual reality on student engagement in the classroom—A critical review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1360574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M., Mustafa, Z. B., Aziz, S. F. B. A., & Maruf, T. I. (2023). Technology adoption for higher education in Bangladesh–development and validation. Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 24(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, 63(8), 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehigan, S., Cenarosa, A. S., Smith, R., Zvavamwe, M., & Traynor, M. (2023). Engaging perioperative students in online learning: Human factors. Journal of Perioperative Practice, 33(1–2), 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. K., & Turner, J. C. (2002). Discovering emotion in classroom motivation research. Educational Psychologist, 37, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). A coherence effect in multimedia learning: The case for minimizing irrelevant sounds in the design of multimedia instructional messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, C. (2025). User-friendly digital tools: Boosting student engagement and creativity in higher education. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A., Kremantzis, M., Essien, A., Petrounias, I., & Hosseini, S. (2024). Enhancing student engagement through artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the basics, opportunities, and challenges. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 21(6), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuci, K. P., Tahir, R., Wang, A. I., & Imran, A. S. (2021). Game-based digital quiz as a tool for improving students’ engagement and learning in online lectures. IEEE Access, 9, 91220–91234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, F. A., Vassileva, J., & Greer, J. (2021). Evaluating a persuasive intervention for engagement in a large university class. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 31(4), 700–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, E., Wong, J., Khalil, M., & Cabo, A. J. (2025). Nonlinear effort-time dynamics of student engagement in a web-based learning platform: A person-oriented transition analysis. Journal of Learning Analytics, 12(2), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C., & Kim, D. (2020). Perception of instructor presence and its effects on learning experience in online classes. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D. (2013). Inclusive technology enhanced learning: Overcoming cognitive, physical, emotional, and geographic challenges (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D. (2019). Technology-enhanced learning: Rethinking the term, the concept and its theoretical background. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D., Ntebutse, J. G., Ahmad, M. Y. A., Cochrane, J., Collin, S., Ganayem, A., Langran, E., Mulla, S., Rodrigo, M. M., Saito, T., Shonfeld, M., & Somasi, S. (2024). Populations digitally excluded from education: Issues, factors, contributions and actions for policy, practice and research in a post-pandemic era. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 29(4), 1733–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D., Shonfeld, M., Appleby, L., Judge, M., & Saito, T. (2018). Digital agency: Empowering equity in and through education. Tech Know Learn, 23, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pellas, N. (2014). The influence of computer self-efficacy, metacognitive self-regulation and self-esteem on student engagement in online learning programs: Evidence from the virtual world of second life. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plak, S., Van Klaveren, C., & Cornelisz, I. (2023). Raising student engagement using digital nudges tailored to students’ motivation and perceived ability levels. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(2), 554–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, R. (2023). Using digital tools to enhance student engagement in online learning: An action research study. In Local research and glocal perspectives in English language teaching: Teaching in changing times (pp. 229–248). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond, P., Heffernan, A., Abawi, L., Brown, A., & Henderson, R. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learning, 22(1), 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2022). Agentic engagement. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 95–107). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reisenzein, R. (1994). Pleasure-arousal theory and the intensity of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riniati, W. O., Jiao, D., & Rahmi, S. N. (2024). Application of augmented reality-based educational technology to increase student engagement in elementary schools. International Journal of Education Elementaria and Psychologia, 1(6), 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, M. D. L., Chan, M. M., Garcia-Cabot, A., Garcia-Lopez, E., & Amado-Salvatierra, H. (2024). The impact of a chatbot working as an assistant in a course for supporting student learning and engagement. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 32(5), e22750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogmans, T., & Abaza, W. (2019). The impact of international business strategy simulation games on student engagement. Simulation & Gaming, 50(3), 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque-Hernández, R. V., Díaz-Roldán, J. L., López-Mendoza, A., & Salazar-Hernández, R. (2023). Instructor presence, interactive tools, student engagement, and satisfaction in online education during the COVID-19 Mexican lockdown. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(5), 2841–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B., Chase, A. M., Robbie, D., Oates, G., & Absalom, Y. (2018). Adaptive quizzes to increase motivation, engagement and learning outcomes in a first year accounting unit. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotar, O. (2022). Online student support: A framework for embedding support interventions into the online learning cycle. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotar, O. (2023). Online course use in academic practice: An examination of factors from technology acceptance research in the Russian context. TechTrends, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotar, O., & Sheiko, K. (2025). Educational technology in Russia: Socio-economic, technological and ethical issues. SN Social Sciences. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh, J., Dengel, A., & Ishimaru, S. (2024). Gaze-driven adaptive learning system with ChatGPT-generated summaries. IEEE Access, 12, 173714–173733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, L. A., Burkholder, G. J., Morad, O. A., & Marsh, C. (2017). Computer-based technology and student engagement: A critical review of the literature. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, L. A., & Louis, M. C. (2011). The engaged learning index: Implications for faculty development. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 22(1), 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K., Dodson, S., Harandi, N. M., Roberson, N., Fels, S., & Roll, I. (2021). Active learning with online video: The impact of learning context on engagement. Computers & Education, 165, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, S., Bonanomi, A., Palamenghi, L., Tuena, C., Graffigna, G., & Riva, G. (2024). Evaluating technology engagement in the time of COVID-19: The Technology Engagement Scale. Behaviour & Information Technology, 43(5), 943–955. [Google Scholar]

- Sholikah, M. A., & Harsono, D. (2021). Enhancing student involvement based on adoption mobile learning innovation as interactive multimedia. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 15(8), 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, G. M., Heddy, B. C., & Lombardi, D. (2015). The challenges of defining and measuring student engagement in science. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V., Padmanabhan, B., de Vreede, T., de Vreede, G. J., Andel, S., Spector, P. E., Benfield, S., & Aslami, A. (2018, June 26–28). A content engagement score for online learning platforms. Fifth Annual ACM Conference on Learning at Scale (pp. 1–4), London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sirakaya, M., & Sirakaya, D. (2022). Augmented reality in STEM education: A systematic review. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(8), 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirani, L. K., & Yamani, H. A. (2024). Enhancing personalized learning with deep learning in Saudi Arabian universities. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 11(7), 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S., Cobham, D., & Jacques, K. (2022). The use of data mining and automated social networking tools in virtual learning environments to improve student engagement in higher education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 12(4), 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, N. A., McNeal, K. S., Atkins, R. M., & Maudlin, L. C. (2020). A novel approach to measuring student engagement while using an augmented reality sandbox. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(4), 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiyantoro, S., Degeng, I. N. S., Kuswandi, D., & Ulfa, S. (2024). Developing gamified learning management systems to increase student engagement in online learning environments. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 14(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, R., & Wang, A. I. (2018, July 9–12). Codifying game-based learning: The league framework for evaluation. In European conference on games based learning, proceedings of the 50th computer simulation conference, Bordeaux, France (pp. 677–686). Academic Conferences International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, D., Fu, P., Wang, Y., Zhang, T., & Qu, X. (2022). Key characteristics in designing massive open online courses (MOOCs) for user acceptance: An application of the extended technology acceptance model. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(5), 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y., & Wang, X. (2021). The effect of two educational technology tools on student engagement in Chinese EFL courses. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(27), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timotheou, S., Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Sobrino, S. V., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Monés, A. M., & Ioannou, A. (2023). Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 6695–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M. C., Cranmer, E., Prim, A., & Bamford, D. (2024). Can augmented reality (AR) applications enhance students’ experiences? Gratifications, engagement and learning styles. Information Technology & People, 37(3), 1251–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T. T., & Nagirikandalage, P. (2025). Insights into enhancing student engagement: A practical application of blended learning. The International Journal of Management Education, 23(2), 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S., & Negi, S. (2025). Role of ICT and Education 5.0 in improving student engagement in distance and online education programs. International Journal of Management in Education, 19(4), 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Truss, A., McBride, K., Porter, H., Anderson, V., Stilwell, G., Philippou, C., & Taggart, A. (2024). Learner engagement with instructor-generated video. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(5), 2192–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J. (2020). The digital divide. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva, J., Cheng, R., Sun, L., & Han, W. (2004). Designing mechanisms to stimulate contributions in collaborative systems for sharing course-related materials. Designing Computational Models of Collaborative Learning Interaction, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Violante, M. G., Vezzetti, E., & Piazzolla, P. (2019). Interactive virtual technologies in engineering education: Why not 360° videos? International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 13(2), 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20(2), 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2022). Effects of augmented reality game-based learning on students’ engagement. International Journal of Science Education, 12(3), 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J., & Ho, H. (1997). Audience engagement in multimedia presentations. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 28(2), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, R. J., de Koning, B. B., Scholten, E., Wong, L. Y. J., & Paas, F. (2024). “Feel free to ask”: Nudging to promote asking questions in the online classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 60, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, N. (2011). Game engagement theory and adult learning. Simulation & Gaming, 42(5), 596–609. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Z. Y., & Liem, G. A. D. (2022). Student engagement: Current state of the construct, conceptual refinement, and future research directions. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YanXia, J., Sulaiman, T., Wong, K. Y., & Chen, Y. Y. (2025). China college students’ perception and engagement through the use of digital tools in higher education—A private university as a case study. Journal of Institutional Research South East Asia, 23(1), 176–195. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. M., Hashim, H., Hashim, H. U., Yahya, Z. S., Sabri, F. S., & Nazeri, A. N. (2019). Kahoot!: Engaging and active learning environment in ESL writing classrooms. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 5(6), 141–152. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Context | TEL Used | Engagement | Theoretical Framework | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cao and Phongsatha (2025) | 472 undergraduate students, Business English course, China. | Foreign Language Intelligent Teaching (FLIT) platform, an AI-powered system that provides personalised analytics and automated feedback. | Cognitive, emotional, behavioural. Engagement scale adapted from Fredricks et al. (2004). Platform usage data, e.g., time spent on tasks. Observations of students’ engagement. | Not employed. | Students with AI system support showed significantly higher cognitive and behavioural engagement. Emotional engagement scores did not statistically differ. |

| 2 | Ding and Xue (2025) | 493 students, English as a Foreign Language course, China. | AI personalization and emotion recognition system. | Cognitive, emotional, behavioural. | Control-Value Theory and Engagement Theory for emotionally responsive AI in EFL. | AI-driven personalisation and emotion recognition positively correlated with engagement, negatively with anxiety; anxiety partially mediated the relationship. |

| 3 | Khanchai et al. (2025) | 98 undergraduate students, Information Literacy and Information Presentation course, Thailand. | Gamified Digital Board Games simulating the real-world. | Engagement was measured using the Game Engagement Questionnaire. | Conceptual model based on Self Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000). | Students with gamification experience showed higher engagement in flow, enjoyment, immersion, and social interaction. |

| 4 | Bakic et al. (2025) | 131 students from Thermal/Fluids course. | Mobile devices (iPads). | Behavioural, social. | Social-constructivist theory, Triple E Framework (L. Kolb, 2017). | Students reported increased engagement with mobile devices for collaboration and note-taking. The use of instructional methods was key. |

| 5 | Tran and Nagirikandalage (2025) | 18 students, Material flow cost accounting course. | Student-created videos and discussion forums in blended learning. | Student views analysed for engagement dimensions, including cognitive, behavioural, emotional, social, collaborative, and technological. | Online engagement framework by Redmond et al. (2018). | Video creation and collaborative discussions enhanced all six engagement dimensions. Student views analysed to develop a framework with six engagement dimensions, including cognitive, behavioural, emotional, social, collaborative, technological. |

| 6 | Fanshawe et al. (2025) | School of Education, online Initial Teacher Education courses, Australia. | Introductory videos, step-by-step assessment instructions, weekly announcements, a number of Activity Tracking tools, nudges. A change from a lecture to a Moodle book. | Data collected included the course survey report (quantitative and qualitative) and course learning analytics (quantitative). | Online Engagement Framework (Redmond et al., 2018) as a conceptual framework. | Redesigned courses increased engagement. Technology-supported design, e.g., ebooks, enabled behavioural guidance and a more interesting interaction with study materials. In terms of emotional domain of engagement, strategic use of inbuilt technologies, e.g., badges, indicated teachers’ care about the student. |

| 7 | YanXia et al. (2025) | 5 students, Bachelor of Education programme, China. | Digital tools Zoom, Google, Canva, WeChat, Zoom. | Not specified. | Not employed. | Digital tools facilitated quick communication, increasing student involvement; three themes: social interaction, collaboration, communication. Reported challenges included technological difficulties, digital fatigue, reduced face-to-face communication. |

| 8 | Al-Hammouri and Rababah (2025) | 95 students, Communication and Health Education, nursing students, Jordan. | Good Behaviour Game. | Behavioural. Participation quality and participation quantity as indicators of student engagement. | Not employed. | Combining quality and quantity contingencies in GBG produced significant engagement improvement; adaptable strategy for online learning. |

| 9 | R. A. Burke et al. (2025) | 38 students, Arts and Science, Architecture, and Education courses, USA. | Google Docs, Kahoot!, PollEverywhere, Phone-like interfaces, avatars, digital badges. Discussion prompts in Canvas or Flipgrid. | Cognitive engagement in asynchronous online discussions. | Not employed. | Students show deep levels of cognitive engagement in asynchronous discussions, in both written and video posts. Students exhibited deeper levels of cognitive engagement when they were given the choice in how to respond. |

| 10 | Navas (2025) | 72 undergraduate students, Primary Education, Spain. | Digital storytelling tools, e.g., Storyjumper, Storybird, Storyboard That. | Not specified. | Not employed. | Strong preference for digital storytelling over traditional methods, digital activities helped students feel more relaxed with teammates, encouraged teamwork, and enhanced creativity. The level of digital activities was high, indicating an increased level of engagement and active participation. |

| 11 | C. Chen and Xiao (2025) | 547 students, Higher Education institutions in China. | Smart Classroom. | Behavioural, social. Measurements of student engagement, such as participation in collaborative learning and motivation, were adapted from Burch et al. (2015). | Social-Cognitive Theory, Digital divide theory, Ecological Systems Theory, Zone of Proximal Development concept. | Integration of smart classrooms enhanced student engagement (Student Engagement is positively correlated with Pedagogical Innovation and Virtual Learning Environments). However, in rural areas, students have limited technologies and prevailing can hinder the classroom activities, leading to lower student engagement (socioeconomic factors). |

| 12 | J. Chen and Huang (2025) | 5 students, Applied Physics course, China. | Virtual Writing Tutor. | Behavioural, cognitive, affective, social dimensions of Learner Engagement with Automated Feedback (LEAF). | Incorporated social dimension into the LEAF framework for a blended collaborative writing course. | Behaviourally, learners followed a four-step procedure (scrutinization, comprehension, evaluation, selection) in offline group discussion to understand, select and transform feedback into an actionable revision plan. Cognitively, comparing, selecting and evaluating were the most frequently used strategies. Affectively, a contradiction was revealed in emotional and attitudinal responses, e.g., the tool was useful but confusing and frustrating. Social engagement is enhanced through group work and emotional support of peers. |

| 13 | tom Dieck et al. (2024) | 173 students, undergraduate, postgraduate, MBA, UK. | Ikea Place VR app, Wanna Kicks shoe try-ons AR, Specsavers AR virtual glasses try-on, BBC Civilisations AR. | Engagement measured through questions about motivation, interest in learning and weather AR enabled the student to apply course material to life. | Further developed the Uses and Gratifications framework by incorporating learning styles based on Kolb’s learning cycle (D. A. Kolb, 2014). | Although reporting changes in engagement levels, the focus is on the gratification factors and earning styles that influence the AR/VR learning experience. Hedonic, utilitarian, sensual and modality gratifications influence AR learning satisfaction, and higher learning satisfaction is associated with higher engagement. |

| 14 | Kahu et al. (2024) | 19 students, Computer Sciences and Information Technology course, New Zealand. | Discord, Microsoft Teams. | Emotional, cognitive, and behavioural engagement are affected by the interplay of institutional and student factors within the sociocultural context (Kahu & Nelson, 2018). | Framework of student engagement by Kahu and Nelson (2018). | The tools addressed the need for a communication tool, supported knowledge sharing and help-seeking engagement behaviours. Supported “organic” conversations, the communication space acted as a virtual equivalent of the physical learning commons. Student belonging and wellbeing are improved by digital learning commons spaces and these act as pathways to engagement and learning. Authors also defined a digital tool categorisation concept: learning Commons Communication Tools. |

| 15 | Roque-Hernández et al. (2023) | 1417 students, School of Business, Mexico. | Interactive communication tools (Microsoft Teams). | Measured using adopted instrument by Park and Kim (2020): communications and perceived instructor presence, self-reported attention. | Not employed. | Interactive tools positively impacted instructor presence, engagement, and satisfaction. |

| 16 | Hisey et al. (2024) | 130 students, Environmental Remote Sensing course. | Interactive storytelling lecture trailers (2 min videos). | Social, cognitive, behavioural, collaborative, and emotional engagement, according to the engagement framework by Redmond et al. (2018). | Online engagement framework (Redmond et al., 2018). | ISLTs enhance behavioural engagement (page views), emotional engagement, and short-term cognitive skills. |

| 17 | Alkhateeb et al. (2024) | 38 graduate students, Teacher training e-course, Iraq. | Electronic gallery-walk (e-gallery-walk) based on Gagne’s Nine Events. | Not specified. | Not employed. | Digital approach enhances student collaboration skills, supporting more active engagement through peer feedback, meaningful discussions, and reflection. |

| 18 | Santhosh et al. (2024) | 22 students, Germany. | Tobii 4C remote eye-tracker with ChatGPT based API integration. | Behavioural. The analysis of gaze patterns to identify engagement or distraction. | Not employed. | Students reported low engagement accessed summaries more frequently, which suggests that the system effectively provides real-time feedback summaries as a support mechanism when engagement is low. |

| 19 | Brown et al. (2024) | 1176 students enrolled across the eight courses, Australia. | Nudging communication strategy. | Behavioural. Student behaviour in accessing key study resources as a proxy for student engagement. | Not employed. | Targeted nudges increased access to resources; excessive nudging led to overwhelm. 5–6 nudges per semester suggested to be effective. |

| 20 | Subiyantoro et al. (2024) | 60 undergraduate students, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Indonesia. | Gamified LMS, with the introduction of badges, gamified challenges, and leaderboards. | Behavioural. Observation sheets are used to observe student active participation in online learning before and after using a gamified LMS. | Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) model. | Gamified elements, including badges, served as a tangible representation of students’ progress and accomplishments that they can showcase. This visual recognition incentivised students to actively participate in learning activities. However, technical and institutional support barriers were also mentioned. |

| 21 | Hamadi et al. (2023) | 18 graduate students, Health care administration course. | Student-made video with discussion questions. | Perceived self-engagement via constructivist learning theory. | Constructivist learning theory. | Half of the students felt more engaged, and students had positive perceptions regarding the alternative approach to online discussion board engagement. Students not only acknowledged being more engaged but also thought more critically about course content as a result of the new approach. |

| 22 | Plak et al. (2023) | 579 students, Statistics course, Netherlands. | Nudges to motivate students to fill out online forms, download a screen-sharing app, and participate in online proctored tests. | Behavioural. Students’ responsiveness to nudging., i.e., their behavioural engagement in online activities in response to nudges. | Fogg Behaviour Model. | Targeted nudges were not more effective than plain nudges in improving student engagement; motivation and prior performance influenced responsiveness. |

| 23 | Anuyahong and Pucharoen (2023) | 100 undergraduate students, Education course, USA. | Mobile learning platform with videos, quizzes, and discussion forums to supplement their learning. | Behavioural. Engagement is measured through the earning analytics data from the mobile learning platform. | Not employed. | The intervention group showed higher logins, time, video views, quizzes, and forum posts compared to control. |

| 24 | Getenet and Tualaulelei (2023) | 28 pre- and 8 post-survey student responses, Early childhood education course, primary education mathematics courses, Australia. | Google Docs, Padlet, Panopto quizzes. | Social, cognitive, behavioural engagement and collaborative dimensions evaluated through survey but excluded the emotional dimension. Observations evaluated emotional engagement. | Online engagement framework (Redmond et al., 2018). | All three technologies enhanced cognitive engagement, but the post-survey identified the video quizzes as strongly enhancing cognitive and behavioural engagement compared with Google Docs and Padlet. Padlet supported the social/collaborative aspect, whilst Panopto- cognitive/behavioural. |

| 25 | Rafique (2023) | 58 students, Functional English and Academic Writing course, Bangladesh. | Zoom breakout rooms, Google Jamboard, Docs, annotate, Chat, Google Classroom Q&A. | Not specified. | Implicit use of Community of learning model (Garrison et al., 2000). | Students enthusiastic due to having a ‘voice’, and Padlet and Zoom features encouraged participation in ongoing discussion. Synchronous and asynchronous modes made communication easier, supported knowledge acquisition by sharing ideas and context with peers. Technical barriers related to access to devices, internet connection. |

| 26 | Mehigan et al. (2023) | 5 students, Perioperative nursing course, UK. | Radio play. | Not specified. | Community of Inquiry (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). | Play enabled reflection on behaviours, fostered belonging, and partnership. The discussion after the play enabled to share ideas in a safe environment and contributed to the greater sense of belonging and engagement with learning. |

| 27 | Hutain and Michinov (2022) | 303 students, Psychology degree. | Audience response system digital learning environment Wooclap (quizzes, questions, slideshows). | Use of Engaged Learning Index (Schreiner & Louis, 2011) to evaluate cognitive, affective (only attention, no social aspect) and behavioural dimensions of engagement. | ELI (Schreiner & Louis, 2011). | High functionalities improved affective engagement (attention); behavioural engagement varied with quizzing. |

| 28 | Karaoglan Yilmaz and Yilmaz (2022) | 68 university students, online Computing Course, Turkey. | Personalised metacognitive feedback based on learning analytics. | Behavioural, cognitive, emotional engagement dimensions, following Sun and Rueda (2012), adapted by Ergün and Usluel (2015). | Not employed. | Personalised metacognitive feedback improved engagement. Metacognitive support, i.e., giving clues and directions to students, supported cognitive, behavioural, and affective dimensions. Including emotional messages in preparing recommendations and guidance are effective in increasing effective engagement. |

| 29 | Smith et al. (2022) | 14 students in control group, 15 in the experimental group. Computing course, UK. | A plug-in MooTwit between Moodle and Twitter (Twitter/email nudging tool), automated messaging generated by the engagement system. | Behavioural. Timeliness of access to study resources, i.e., data from the Moodle database logs. | Not employed. | The experimental group showed positive performance increase with automated nudging. Repeated prompting had a cumulative effect over time. |

| 30 | Kim et al. (2022) | 22 students, Business Administration, English language, Multimedia communication, and software engineering online courses, Vietnam. | EduNext mediation tool. | Based on the Redmond et al.’s (2018) framework. Concepts of engagement and involvement are used interchangeably. | Online engagement framework (Redmond et al., 2018), Activity Theory (Engeström, 1987). | EduNext had a great influence on social engagement, whilst cognitive engagement was reported mostly at a surface-level. Students reported mixed effects on emotions, ranging from curiosity, motivation to worry. |

| 31 | K. Burke et al. (2022) | 40 students, Teacher education courses, USA. | Digital tools in an online learning environment. | Engagement is discussed through mapping of ‘pedagogical touchpoints’, i.e., encounters students had with their online learning environment, student voice on what is valued and identified as ‘engaging’. | Authentic personhood in education (K. Burke & Larmar, 2020). | Identified engaging qualities that students valued, i.e., pedagogical care. Pedagogical care can be strategically exercised via technology enhanced inclusion and connection. |

| 32 | Orji et al. (2021) | 228 students, Biology class, Canada. | Socially oriented persuasive strategies used in MindTap and Student Advice Recommender Agent system that provides personalised support based on data from student academic and personal history, and current activities. | Behavioural participation in the activities within the evaluated systems, measured by interaction data (time-stamped logs, number of logins, time spent on the system, and engagement score, e.g., time spent and completed activities). | Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1971). Confirms findings on persuasive strategies (Vassileva et al., 2004). | Persuasive intervention significantly increased engagement over time- students who used the SARA system with persuasion were more attentive to information provided by the system because they were more active with the system. Personalisation of persuasive strategies based on receptiveness of a student amplified their effect on engagement. Intervention increased students’ behavioural engagement with the MindTap system, e.g., access to e-books, interactive study tools and materials. |

| 33 | Teng and Wang (2021) | 268 undergraduate and graduate students, EFL courses, China. | LMS, social networking tools. | Behavioural, cognitive, emotional, educational technology engagement (using adapted scales). | Not employed. | LMS influenced engagement more significantly than social networking; emotional engagement had the biggest impact. |

| 34 | Imlawi (2021) | 272 undergraduate students, English course for non-English speakers, Jordan. | M-learning application with sound elements (voiceovers, sound effects, background music). | Behavioural, cognitive (self-reported attention, curiosity, imagination) and emotional (self-reported fun). | Webster and Ho (1997) engagement measurement for information systems. Arousal research (Moreno & Mayer, 2000). | Voiceovers positively influenced engagement, confirming arousal theory. |

| 35 | Seo et al. (2021) | 116 students. | Learning with video. | Emotional, cognitive, behavioural experience (Lalmas et al., 2022). | The Interactive, Constructive, Active, and Passive (ICAP) framework used as a lens through which student actions are interpreted. | Identified the following engagement goals: reflect, flag, remember, clarify, skim, search, orient, and take a break. The goal of engagement varied by context (exam week, when re-watching). Online students showed more strategic use of technology. |

| 36 | Weijers et al. (2024) | Experiment 1 (1011 students), Experiment 2 (449 students), Netherlands. | A video booth nudge, a checklist nudge, a goal-setting nudge, and the prompt nudge were implemented. | Engagement is not explicitly discussed, yet the focus is on the measurement of students’ behaviour and self-reported planning behaviour (agentic engagement). | Not employed. | Nudges marginally increased questions asked. This effect was driven by students who were already asking many questions. However, the nudge had no effect on the learning outcomes of students, and no effect of the nudge on behavioural and agentic engagement, nor a relation between extraversion and the nudge. In-class behaviour is more susceptible to being nudged, like asking questions during a lesson. |

| 37 | Nuci et al. (2021) | 257 students, Human–Computer Interaction course, Kosovo. | Game-based digital quiz tools, e.g., Kahoot! and Google Form quiz platform. | Behavioural engagement and affective cognitive reaction (fun, engagement). | Learning, Environment, Affective cognitive reactions, Game factors, Usability framework (Tahir & Wang, 2018). | Students favoured Kahoot! due to its positive effect on class dynamics and gamification components, including competition, bonus points, timeliness, music. Performing online quizzes positively impacted participation in online classes compared to participation in courses with no quizzes. |

| 38 | Sholikah and Harsono (2021) | 89 students, Indonesia. | M-learning. | Student engagement was measured using a scale developed by. Engagement and involvement used interchangeably. | Engagement scale developed by Handelsman et al. (2005). | M-learning adoption increased participation; productivity in learning was a key advantage. |

| 39 | Lacey and Wall (2021) | 170 students, Microbiology course, Indonesia. | Teaching videos demonstrating lab techniques which are core to the syllabus. | Behavioural, cognitive. Views of video content before lab sessions, impressions click-through rates which measure engagement with video impressions seen on YouTube. | Not employed. | Videos improved understanding, engagement, and satisfaction. In-house videos maximised engagement: students preferred videos produced in a familiar environment and using their accustomed equipment (in-house), which is suggested as a likely contributor to the high engagement levels with the in-house videos. The lesser ‘engagement’ of second year than third year students, i.e., lower proportion of students who viewed videos before lab sessions |

| 40 | Ahshan (2021) | 153 students, Engineering courses, Oman. | Moodle platform, Google Meet, Google Chat, and Google breakout rooms, Jamboard, Mentimeter. | Self-reported effectiveness and interactivity of the framework elements. The concept of active engagement is not discussed. | Not employed. | Proposed a Framework of Active student engagement. Implementation of framework supported student interaction and increased student engagement, as reported by students. 11% of students reported issues with their internet connection likely due to internet connection quality and students’ geographic locations. |

| 41 | Bouchrika et al. (2021) | 863 students, Algeria. | Gamification elements integrated into the e-learning system. | Different metrics to measure behavioural engagement and cognitive engagement, e.g., by number of asked questions, posted answers, cast votes, browsing statistics collected from Google Analytics. | Not employed. | Gamification increased engagement with large content volume and resulted in more earned points. |

| 42 | Holbrey (2020) | 44 undergraduate students, Primary education course, UK. | Kahoot! | Involvement (Vivek et al., 2012) and behavioural engagement. | Not employed. | Kahoot! improved engagement and concentration, retention results ambiguous, needing further study. No technical difficulties in implementation. |

| 43 | Le (2020) | 50 students, ESL blended learning course, Vietnam. | Classcraft app. | Participation, rush, flow, emotional, cognitive, agentic (Kalinauskas, 2018). | Not employed. | Gamification enhanced behavioural, emotional engagement, but cognitive less strong. Regarding behavioural engagement, the results revealed three main themes: learner participation, effort making, and contribution. Gamification helped to encourage learners to participate, gain effort and devotion to learning. Problems with collaboration mainly accounted for the boredom and disengagement. The evidence of engagement was mostly witnessed in face-to-face learning, especially with emotional engagement. |

| 44 | Gay & Betts (2020) | 3386 students, Social Sciences, Information Systems courses, Caribbean university. | Group-work assignment using Online Human Touch (OHT) strategies, integrated into an Information Systems. | Behavioural. Engagement is measured through behavioural indicators and posts and self-reported feedback. | OHT as a conceptual framework. | The assignment simulated a real-world business ‘eMeeting’ to proactively increase student engagement and retention. EMeeting increased emotional and behavioural engagement; cognitive engagement limited. |

| 45 | Violante et al. (2019) | 30 students, Entrepreneurial course. | VR: 360-degree videos, also known as immersive videos or spherical videos, are shot with a camera that captures a 360-degree view. | Behavioural (effort, persistence), emotional (fun, enthusiasm), cognitive (attention, focus) aspects of engagement. Student engagement is discussed at the level of learning within a single activity and the level of a whole learning experience. | Multimedia design principles proposed by Mayer (2008). | 360° videos increased involvement, concentration, creativity, and enjoyment, fostered optimal learning. |

| 46 | Rogmans and Abaza (2019) | 117 students-simulation based class, 83 students- traditional class, Strategic Management course, UAE. | International Business Strategy Simulation Game. | Behavioural, through the use of Engagement Score, questionnaire based on Whitton (2011). | Not employed. | Results showed that engagement scores were positive in both settings but were higher in the traditional classroom. The conclusion is that simulation methods may not be superior to traditional methods in supporting student engagement. |

| 47 | Yunus et al. (2019) | 40 students, third-year Teaching ESL undergraduate course, Malaysia. | Kahoot! | Perceived value of Kahoot! for engagement, self-reported by students. No definition of engagement is provided. | Not employed. | 85% of students agreed Kahoot! made learning fun and effective. Based on these results, the authors concluded that Kahoot! can enhance engagement and active learning. |

| 48 | Bechkoff (2019) | Online Consumer Behaviour courses, USA. | Choose-your-own-adventure game in the classroom via the open- source programme Twine. | Perceived helpfulness and enjoyment of the game. | Building on operant conditioning, motivation theory, self-efficacy theory, the novelty effect research. | Twine game perceived as helpful to solve the quiz, fun, and engaging. Some reported as inspiring deeper thinking and helped to better understand the material. |

| 49 | Ross et al. (2018) | 849 students, accounting course, Australia. | Adaptive quizzes which make use of adaptive learning technologies. | Behavioural. Time and energy invested in educationally purposeful activities (Kuh et al., 2008). | Not employed. | The majority of students agreed that receiving regular feedback from the adaptive quizzes motivated them to keep trying, it was beneficial to receive immediate feedback. Over a quarter) indicated that they disliked the limited responses provided by the adaptive quizzes and expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of detail of the feedback they received. |

| 50 | Chang and Yu (2018) | 93 students majoring in biotechnology, Taiwan. | AR ArBioLab app with five learning units: microscope structure, microscope operation, animal and plant cell observation, frog dissection, and frog bone structure. | Not specified. | Not employed. | AR integration improved students’ autonomous learning, lab skills, and understanding of scientific knowledge. The use of the AR app resulted in the shorter time of experiments’ delivery. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotar, O. Beyond Technology Tools: Supporting Student Engagement in Technology Enhanced Learning. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121617

Rotar O. Beyond Technology Tools: Supporting Student Engagement in Technology Enhanced Learning. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121617

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotar, Olga. 2025. "Beyond Technology Tools: Supporting Student Engagement in Technology Enhanced Learning" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121617

APA StyleRotar, O. (2025). Beyond Technology Tools: Supporting Student Engagement in Technology Enhanced Learning. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121617