2. Literature Review

In programming education, GenAI chatbots have been integrated into both teaching and students’ independent learning, proving suitable for facilitating learning in students of all ages. Students have used the generative capabilities of GenAI to generate hints to assist them in completing programming assignments (

Pankiewicz & Baker, 2023), writing and debugging code (

Sun et al., 2024), explaining programming concepts (

Lee et al., 2024), and to access programming resources (

Abdulla et al., 2024). Due to its ability to perform various tasks, many have come to view GenAI chatbots as a replacement or supplementary tutor.

Phung et al. (

2023) compared the support and feedback generated by ChatGPT with feedback from human tutors in a wide variety of programming education scenarios such as helping students to resolve various obstacles encountered while programming, grading students’ code, explaining programming concepts, and even generating problems for students to practice on. Their work discovered that the GPT4 model of ChatGPT provided feedback nearly equal in quality to that given by human tutors, suggesting the value of GenAI in facilitating programming learning.

The introduction of GenAI has overall been welcomed by students. GenAI has established itself as an important source of help for struggling programming students (

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025). GenAI chatbots are commonly viewed as helpful and accessible sources of assistance when programming (

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025;

Jiang & Nakatani, 2025). Many students found GenAI chatbots useful as it could facilitate them in looking for information, provide guidance on completing programming tasks they are unsure of, debugging, and generating code (

Vaithilingam et al., 2022;

Scholl & Kiesler, 2024). Some students find it easier and faster to learn programming when assisted by GenAI tools as well (

Oyelere & Aruleba, 2025). Students also find GenAI chatbots very easy to use while learning, as they respond to their requests quickly and can keep track of their past requests, making each interaction smooth and efficient (

Scholl & Kiesler, 2024). Students are also able to customize and modify the output generated by GenAI learning assistants to suit their learning needs, making it easier for them to obtain the information or solutions they want (

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025).

Perhaps due to these positive attitudes towards GenAI, GenAI chatbots are widely used by students to facilitate their learning of programming. A survey of university students learning programming found that most students already use ChatGPT for assistance when completing assignments or in their learning (

Scholl & Kiesler, 2024;

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025;

Oyelere & Aruleba, 2025). At the same time, students remain conscious of the risks associated with using GenAI in their learning and tailor their usage of this technology to avoid these risks. Due to the nature of how LLMs understand prompts and generate responses, students understand that AI-generated responses may be inaccurate due to potential biases in information or hallucinations, and report needing to verify the reliability of these responses (

Scholl & Kiesler, 2024). Students also trusted code written by themselves over AI-generated code, reflecting their distrust in GenAI (

Keuning et al., 2024). Aware of the risks of overreliance on GenAI tools, students still work on their programming assignments independently, choosing to write solution codes on their own instead of relying on GenAI for solutions (

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025). There also remain small groups of students who refuse to use GenAI in their learning or prefer using traditional learning resources due to concerns over plagiarism and its long-term effects on their learning (

Lepp & Kaimre, 2025;

Scholl & Kiesler, 2024).

Most studies on GenAI use and students’ perceptions of its use in programming education focus on university students (

Ahmed et al., 2024;

Dube et al., 2024). Comparatively, fewer studies explore the factors influencing GenAI use and perceptions of its use in high school education. As younger students, especially those born in the Generations Alpha and Zeta (Gen Z), have interacted closely with technology since childhood, they may be more receptive towards GenAI use in their studies than older students.

Höfrová et al. (

2024) describes these groups of students as being brought up with technology being a common and unavoidable way through which to experience life. Gen Z have also been shown to exhibit greater trust in GenAI tools and higher usage of GenAI in their learning (

Zubair et al., 2025), even in our study’s present context of Singapore (

Nguyen et al., 2025). Hence, it is important to explore the drivers behind high school students’ attitudes and intentions to use GenAI in their learning.

The DTPB (

Taylor & Todd, 1995) extends the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by breaking down attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control into specific belief structures, enabling more fine-grained explanation of how and why users decide to adopt a technology. In this study, the DTPB serves as the theoretical lens for analyzing the factors shaping students’ attitudes toward and intentions to use MyBotBuddy to learn programming. By using the framework to interpret students’ perspectives, we assess how closely their expressed beliefs align with the constructs outlined in the DTPB. The DTPB is a decomposed version of the original TPB (

Ajzen, 1991), where the various beliefs associated with each factor in the TPB are broken down in detail. The original TPB (

Ajzen, 1991) predicts that an individual’s performance of a behavior is dependent on their intention to perform it and their perceived behavioral control over performing it, which refers to their belief in their ability to carry out the behavior. One’s intention to perform a behavior could then be influenced by one’s attitude towards performing it, subjective norms, and one’s perceived behavioral control.

To identify more specifically the factors influencing individuals’ usage behavior of a technology,

Taylor and Todd (

1995) elaborate on the TPB (

Ajzen, 1991) to include additional belief structures that contribute to the factors listed in the original theory. Individuals’ attitudes consist of the following beliefs: the relative advantage that using a piece of technology brings compared to its alternatives, the perceived complexity of using that technology, and its compatibility with the individuals’ values or needs. Individuals who believe that specific technology is more beneficial than its alternatives, easy to use, and suitable for their needs are predicted to intend to use the technology. Subjective norms are also broken into peer influence and influence of one’s superiors. Perceived behavioral control was decomposed into self-efficacy beliefs, or one’s belief in their competence to use a technology, as well as facilitating conditions to use the technology. In the context of GenAI use in programming education,

Skripchuk et al. (

2024) has shown that programming beginners were primarily motivated to use GenAI resources due to their personal attitudes about how useful it was to their learning, and less so by subjective norms.

Ivanov et al. (

2024) also investigated the link between attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions to use GenAI in education amongst educators and university students. They discovered that perceived strengths and benefits of GenAI have an indirect positive effect on students’ intentions to use GenAI through the direct positive influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Students who perceive GenAI tools as being beneficial to their learning, receive their peers’ endorsement of GenAI tools, and perceive themselves as being capable of using GenAI are thus more motivated to use it while learning programming. The TPB has thus shown itself to be an apt tool to explain students’ intentions to use GenAI in their studies. However, research on the detailed belief structures surrounding students’ attitudes and intentions to use GenAI resources, as described in the DTPB, remains scarce.

The literature also suggests that in addition to the belief structures listed in the DTPB, other individual factors may also influence students’ attitudes and intentions to use GenAI in their studies. Users’ subject expertise, which in this context refers to students’ programming proficiency, has also been shown to play an indirect role in influencing behavioral intentions.

Ahn and Park (

2012) demonstrated how customers with more product expertise choose to rely less on recommendation agents when shopping online and find these agents less useful than customers who were not familiar with the products being purchased. Instead, experienced customers preferred when agents gave them more control over their purchasing behavior and utilized their existing expertise, such as allowing them to filter for products instead. Due to their familiarity with the products, experienced customers preferred to shop independently instead. Similarly, students who are already proficient in programming may prefer to learn programming and code independently instead of relying on a GenAI educational chatbot to provide guidance while learning.

Boguslawski et al. (

2024) explored students’ perceptions of using GenAI tools to learn programming, discovering that as students become more familiar with programming, their needs and preferences regarding using these tools change accordingly. This suggests that as students’ learning needs change alongside their familiarity with programming, there may be differences in how they use and perceive GenAI tools. However, in an investigation of Bachelor’s and Master’s level computing students’ perceptions and uses of GenAI tools to learn,

Keuning et al. (

2024) found that master’s students were more receptive towards using GenAI tools than bachelor’s students. Master’s students also showed a greater preference to use GenAI tools as a help-seeking strategy when learning programming than bachelor’s students. These results suggest that more advanced programming students may instead have more positive attitudes and stronger intentions to use GenAI tools than less advanced students. The literature thus displays mixed findings about the effect of subject expertise on individuals’ behavioral intentions. The present study aims to explore how subject expertise may influence students’ intentions to use GenAI chatbots to learn, within the context of Singapore GCE ‘O’ Level Computing students. Specifically, do students who are more well-versed in computing and score higher grades in the subject interact with or carry different attitudes towards GenAI than their peers with poorer grades?

This study thus intends to address the following research questions:

To what extent can the DTPB describe and explain secondary school students’ attitudes toward and intentions to use a GenAI chatbot, MyBotBuddy, to learn programming?

Are there any differences in students’ interactions with, attitudes towards, and intentions to use a GenAI chatbot, MyBotBuddy, to learn programming across students with varying levels of academic performance in computing?

4. Results

RQ1: To what extent can the DTPB describe and explain secondary school students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy to learn programming?

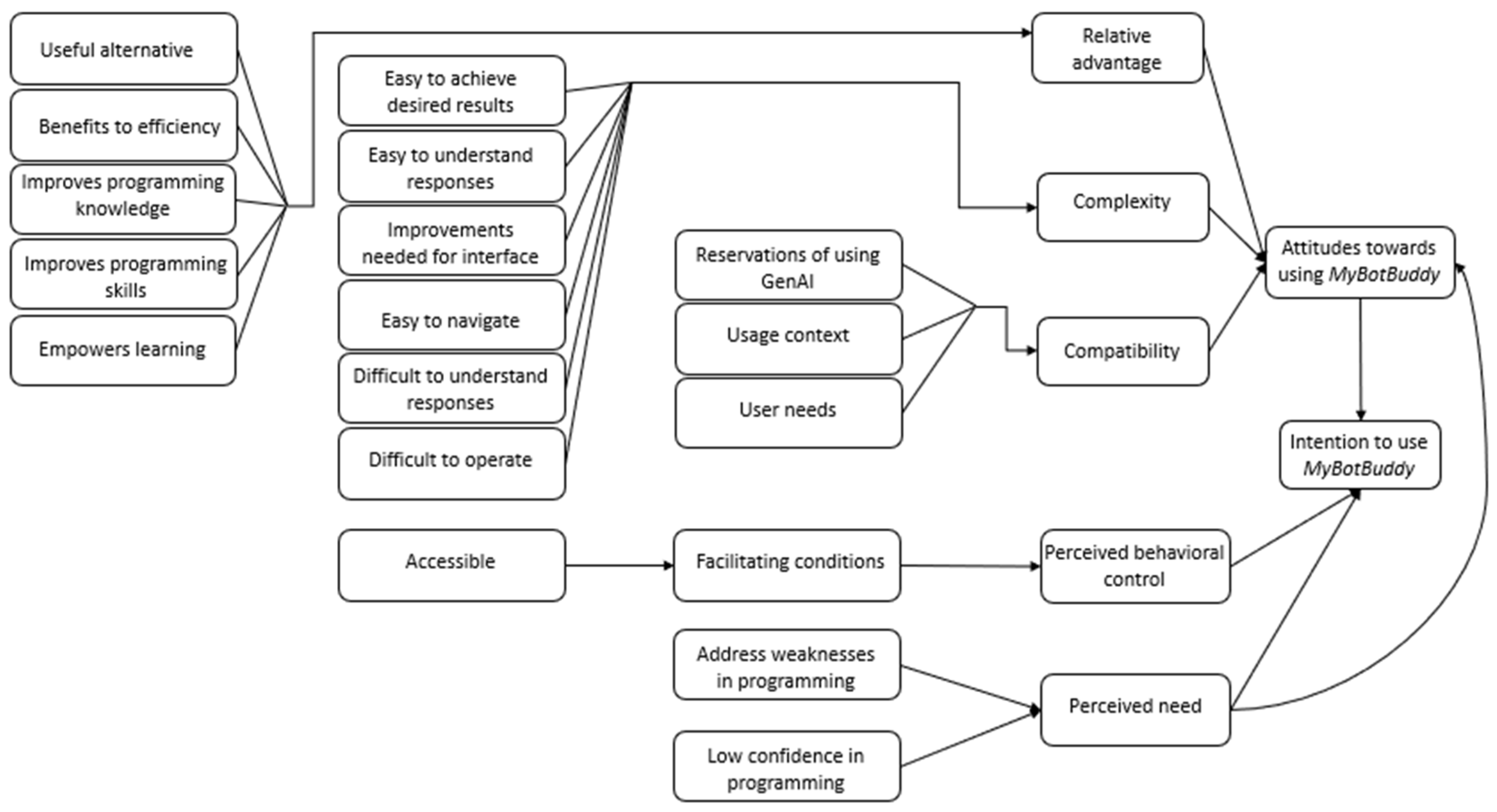

The thematic analysis conducted revealed 18 distinct themes, which were then categorized under corresponding concepts found in the DTPB, namely intention to use, relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, and perceived behavioral control. An additional category which was not represented in the DTPB also emerged: perceived need.

Table A1 in

Appendix A demonstrates the codes, themes, and their corresponding constructs in the DTPB.

The DTPB hypothesizes that students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy can be represented by the following concepts: the perceived relative advantage provided by MyBotBuddy over other alternatives, the perceived complexity of using MyBotBuddy, and the compatibility between MyBotBuddy and the user’s values and needs. The majority of students’ responses focused on these various perceptions that comprised their attitude towards using MyBotBuddy to learn programming.

4.1. Advantages and Benefits of Using MyBotBuddy

Students were very positive about the relative advantages and benefits that using MyBotBuddy could bring to their programming learning. Five themes were identified as reflecting these advantages: MyBotBuddy as a useful alternative to other information resources (n = 14), benefits to one’s programming efficiency (n = 13), the ability of MyBotBuddy to improve their programming knowledge (n = 16), the ability of MyBotBuddy to improve their programming skills (n = 12), and students’ empowerment when learning programming (n = 7). When asked about their experience interacting with MyBotBuddy, many students spontaneously compared it to ChatGPT, asking a teacher, or searching for web resources online. Students commonly appreciated how they could find the specific solutions or information needed using MyBotBuddy more directly and efficiently compared to other GenAI tools. Students felt that MyBotBuddy was better than ChatGPT at understanding their prompts and producing specific solutions (P8), as well as at producing concise, relevant solutions appropriate for students’ programming level and context (P11). MyBotBuddy was also seen as a quickly accessible alternative to answering their questions about programming content than asking a teacher (P18, P11). Students also highlighted how using MyBotBuddy while completing programming assignments could help them to code more efficiently by helping them to organize data (P13), decompose programming problems (P16), point out errors in their code (P8), generate code without errors (P3), and obtain information immediately without needing time to search for it (P7). One student pointed out that it would be particularly useful for improving their efficiency in debugging when working with complex projects with many different components, as it can quickly comb through the sections of code to identify and resolve any errors (P11). MyBotBuddy’s biggest perceived advantage over other resources was its ability to facilitate their learning of programming concepts and knowledge. Students pointed out MyBotBuddy’s usefulness in facilitating revision of programming concepts (P5) and providing access to a wide range of educational resources (P6). They also felt that MyBotBuddy was useful in effectively supporting their learning as it provided concise and personalized step-by-step explanations to scaffold their understanding of new programming concepts (P7, P8). A student emphasized how:

“instead of just giving you the code it also explains how the code works and everything. So then you can learn how to do it and try to understand”.

(P14)

Instead of passively generating answers for students like other GenAI tools, students appreciated that MyBotBuddy focused on explaining the logic behind the code to improve their foundational knowledge instead. Students also highlighted MyBotBuddy’s helpful and relevant suggestions that facilitated an improvement in their practical programming skills. For instance, one student found the chatbot useful to make their code more professional by using its suggestions to shorten the code to make it more efficient (P10), while another student described how MyBotBuddy suggested better alternative functions to replace existing sections of their code (P11). Students found these suggestions extremely applicable as they “managed to implement the suggestions onto the other program” (P10), suggesting that they became more proficient in writing program codes after learning from MyBotBuddy. Lastly, there were some students who also found this method of learning programming more empowering. These students preferred asking a GenAI chatbot for programming help over asking teachers or friends as it allowed them to study and learn more independently. For instance, a student mentioned that they did not have any family members who could help them with coding and that their teacher was sometimes too busy to answer all students’ questions, thus using MyBotBuddy allowed them to independently resolve any confusion they had while studying programming alone (P1). Another student also felt more motivated when studying with MyBotBuddy’s assistance since it provided help to understand the content without having to rely on others (P2). MyBotBuddy also generated additional practice questions and prompted students to further explore how sections of code work, thus encouraging deeper learning (P1, P12). Hence, the concept of relative advantage of using MyBotBuddy from the DTPB was well reflected through the various academic benefits of using MyBotBuddy listed by students in the interview.

4.2. Attitudes Towards to Learning Programming

Another aspect that comprised students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy in learning programming, their perceived complexity of using such technology, was also well-represented in their responses. Students’ opinions on the complexity of using MyBotBuddy were mixed, with some expressing difficulties while others interacted with the chatbot easily. Six related themes were identified: three reflected positive perceptions about how easy it was to use the chatbot, two reflected concerns about the difficulty of using the chatbot, while one theme consisted of suggestions for improving the interface. The students who found MyBotBuddy easy to use while learning programming discussed how they found it easy to obtain the responses they wanted (n = 10), to navigate the chatbot (n = 7), and to understand the generated responses (n = 16). Some examples of how MyBotBuddy made its generated responses easier for students to understand include breaking down the content into several smaller steps (P7, P9), providing examples alongside explanation of content (P10, P12), commenting on generated code to explain its function (P14), and using simple phrasing instead of technical jargon to explain programming concepts or code (P10, P11). Students felt that these features helped them to better “internalize the explanation” (P8). Students also commented on how easily MyBotBuddy was able to understand their prompts, as “I don’t have to explain in detail what I want to come out” (P3) and “it [MyBotBuddy] just cranks out the response” (P4). This reduced the effort needed to obtain specific answers. Most students also found it easy to navigate MyBotBuddy’s interface. While some attributed it to their prior familiarity with GenAI chatbots (P5), others felt that it was because the interface was simple without complicated features or options (P7, P9, P13). One student pointed out how MyBotBuddy made it easier for them to view the generated responses in context:

“when I was getting them to debug my code, they actually made reference back to it, I didn’t have to copy and paste it [two] separate time[s]”

(P8)

However, some students still experienced difficulties in operating the chatbot (n = 5) and understanding the generated answers (n = 11). Students who had difficulties understanding the responses generated by MyBotBuddy seemed to disagree on the cause of this issue. While some felt that MyBotBuddy had oversimplified its code solutions without sufficient explanations (P15, P17), others felt like the responses were overwhelmingly lengthy and over-explained (P16). Other causes listed by students included overcomplicated answer formats and the inclusion of advanced programming concepts beyond their scope of learning. One student explained that “it’s the way that they write the program that’s hard to understand at first glance” (P9), and that the generated code was “a bit confusing because some of the code they just pack into one line” (P13). Another student mentioned that “sometimes MyBotBuddy uses terms that I haven’t learned yet” even when not prompted to do so, for instance

“just now I was putting into my code, and I was asking it to help me debug it and it told me something about logging which I haven’t learned yet. So I was quite perplexed”.

(P5)

Most students who mentioned these issues expressed confusion while reading the responses, which led to difficulties using MyBotBuddy. Some also had difficulties with getting the chatbot model to produce their desired answers:

“I already specified what I want to change but it also wanted to change another one [section of code] and then when I send another [version of] my revised program, it also wanted to change the other parts of it again, and then so it’s kind of repeating what it wants”.

(P10)

Such feedback is further supported by students’ suggestions for improvement, such as adding a function for users to indicate their current level of programming expertise to match the generated solutions to students’ level (P5) or reducing the amount of text generated in one response (P11). Other popular suggestions include allowing students to open and toggle between multiple chats at once (P1), a feature to pin selected messages or search chat history (P7) and automatically displaying newly generated responses from the start rather than from the end of the text (P12). These suggestions all imply concerns about the convenience of viewing generated responses, which may be an important consideration for students. These themes hence illustrate complexity of using GenAI chatbots as one of the main components of students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy, as theorized by the DTPB.

Another key factor influencing students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy was their compatibility with GenAI chatbots. While students maintained an overall positive outlook of using MyBotBuddy to learn programming due to its perceived relevance to their usage context (n = 5) and needs as programming students (n = 14), some still harbored reservations towards using GenAI in their studies (n = 8). Most students felt that MyBotBuddy was relevant to learning programming as they found it useful for meeting specific needs while learning programming. For instance, students felt that it was especially appropriate for helping less experienced students to learn programming (P1, P16). One student expressed that “when I first started out, I actually struggled to use the functions” and

“didn’t know how to start a program. Once you have that fundamentals because of the chatbot, where it helps you to develop that critical thinking skill, then you’re able to learn computing efficiently”.

(P17)

They suggest that MyBotBuddy is suitable to help weaker students to develop the foundational thinking skills needed in programming. The chatbot could also meet students’ needs while learning by providing a starting point when they were stuck on a problem, facilitating revision or preparation for class, or guiding them to further explore programming concepts. Students described how they found MyBotBuddy useful in helping to recall and apply concepts previously learned in class (P2, P3, P6) as well as explaining new concepts ahead of the syllabus to help them when preparing for class (P5, P18). Students also appreciated that it could help them to generate a skeleton code as a reference for working on programming problems, especially when they were unfamiliar with where to begin (P5, P12). However, despite acknowledging these benefits, some students were hesitant to embrace the use of GenAI in education due to ethical concerns about plagiarism, concerns about overreliance, and general distrust of the accuracy of or relevance of information generated. A student elaborated that being able to generate solutions using GenAI tempted them to be lazy to complete assignments (P12). However, students still described attempts to prevent over reliance on GenAI while learning, such as requesting explanations of the logic behind generated solutions (P10), only using GenAI when they were stuck on a problem (P15), or going through the generated answers with a teacher (P13). These allow students to maintain proactive while learning (P13) and ensure their understanding of fundamental programming concepts. Interestingly, a student recounted negative past experiences where they received misinformation from GenAI yet were still willing to use GenAI despite its inconsistency (P1). This suggests that some may still be willing to overlook their concerns due to the usefulness of GenAI alone. Another student cited the nature of LLMs in general, where responses are generated through recognizing patterns in text and predicting responses based on this data without understanding the meaning of the words, as the reason for their distrust of the information generated (P16). Overall, this suggests that students pay close attention to how compatible GenAI is to their needs while learning programming and its alignment with their ethical concerns in forming their attitude towards using this technology in their education.

4.3. Behavioral Control and Subjective Norms

Notably, the construction of perceived behavioral control and subjective norms did not feature prominently in students’ responses, suggesting that it may not play a significant role in influencing students’ intentions towards using MyBotBuddy. This aspect of the DTPB may thus not be as important to Singapore secondary school students when deciding whether to use GenAI to learn. The topic was briefly mentioned by a few students in terms of facilitating conditions that motivated them to use MyBotBuddy (n = 3), such as how being able to independently and immediately access information or help made using the chatbot more relevant to learning programming. Separately, one student did refer to their confidence in their ability to use MyBotBuddy effectively, stating that “even though I understand now, but sometimes I might not be able to understand” (P2). This student was hesitant to use MyBotBuddy as they were concerned that they may not understand its content and would still need additional help from peers to use the chatbot. Perceived behavioral control was overall limited in describing why students intended to use MyBotBuddy. However, this may be influenced by the smaller sample size employed in the present study. A more in-depth interview with a larger number of participants may be useful to uncover more opinions about this construct.

4.4. Perceived Need to Use MyBotBuddy

Another concept outside of the DTPB emerged that students associated with their attitudes towards and their intention to use MyBotBuddy: students’ perception of how much they needed to rely on using the tool. This concept was often mentioned in relation to students’ perceived competence in programming. Two themes were linked to this concept: addressing one’s weaknesses in programming (n = 5) and low confidence in one’s programming abilities (n = 4). Students who expressed low confidence in their programming abilities often also expressed anxiety about writing code. One student mentioned that “I’m not very good at programming so inside me I don’t want to touch computing because I know I cannot do” (P2), while another “was afraid, like I would mess up when I tried it myself” (P8). These students explained that they felt motivated to use MyBotBuddy as they needed it to “help me solve my problems” (P2) and code successfully. One student even explained that

“usually those who don’t use the chatbot, I think they are already well-versed in coding themselves, so I don’t think they need to rely on the chatbot unlike me.”

(P1)

Students may see relying on GenAI to learn programming as only being necessary when one is not proficient in programming. Therefore, students’ intentions to use MyBotBuddy were strengthened by their lack of confidence in their programming skills. Students also discussed how useful MyBotBuddy was in addressing their weaknesses when programming as well as how they intended to use it in the future to help make up for these weaknesses. MyBotBuddy could provide hints when students were struggling to recall functions or concepts (P1, P4), assist those who struggle with identifying errors (P2, P13), or guide students who struggle to translate their ideas into code (P1, P12). As MyBotBuddy can help students complete tasks that they usually fail to complete independently, students hold more positive attitudes towards using it and find it useful to their learning. This perception of MyBotBuddy’s usefulness in helping students make up for their weaknesses in programming then drives their intentions to continue using the chatbot. When asked whether they would continue using MyBotBuddy, a student responded:

“I think I would, because I cannot really identify my problems sometimes, so my code overall it will be syntax error or cannot code out the relevant output that I was supposed to achieve. So I think it could help me in a way also”

(P2)

Hence, students’ awareness of their programming abilities drives them to find using GenAI educational resources necessary as it can help to address their weaknesses in the subject.

4.5. Intentions to Use

Almost all students intended to continue using MyBotBuddy and were willing to use GenAI chatbots in general (

n = 17). The most common reason cited by students for wanting to continue using MyBotBuddy to learn programming is its ability to scaffold students’ learning and improve their knowledge of programming. Students indicated that they were keen to use it again to facilitate revision for classes or examinations (P6, P13), learning new programming languages (P8, P17), and even for learning other academic subjects (P13). This suggests that in considering whether to use a GenAI educational chatbot, students pay most attention to its usefulness in facilitating their learning and acquisition of programming knowledge. Other reasons cited by students also relate to the concept of relative advantages brought about by using the chatbot, such as being able to complete programming assignments more efficiently with its aid (P3), and its usefulness as a substitute for teachers when they are unavailable (P1). As hypothesized in the DTPB, the data thus aligns with the crucial role of attitude, through students’ perceptions of the academic advantages gained from using GenAI chatbots, on influencing their intention to continue using this technology. As shown in

Table 2, most themes aligned with the decomposed belief components of the DTPB, particularly those related to relative advantage, complexity, and compatibility. However, the analysis also revealed an emergent construct we term perceived need, which reflects students’ reliance on MyBotBuddy due to low confidence in their programming abilities. This construct is not accounted for in the original DTPB model and suggests a meaningful extension for understanding GenAI adoption in skill-based secondary learning contexts.

In conclusion, the DTPB accurately described most of the attitudes and perceptions that students hold regarding using MyBotBuddy through the concepts of relative advantage, complexity of using MyBotBuddy, and compatibility with user values or needs. However, these concepts did neglect to reflect the attitudes of a small group of students towards using MyBotBuddy, suggesting a need to continue to refine and expand the DTPB framework. These students’ attitudes were driven by their perceived need to rely on the chatbot as they learn programming. The relationships between students’ attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy and its influence on their subsequent intentions to use the chatbot were also aligned with the theorized relationship in the framework. However, other concepts crucial to the DTPB, such as subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, were poorly represented in the data, suggesting that secondary school students from Singapore did not value these factors in their decisions to use GenAI technology while learning programming. Hence, DTPB was only partially successful in explaining students’ intentions to use MyBotBuddy.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the identified themes and their corresponding components of the DTPB and the relationships between various components of the DTPB reflected in the interview data.

RQ2: Are there any differences in students’ interactions with or attitudes towards and intention to use MyBotBuddy to learn programming across students with varying levels of academic performance in computing?

4.6. Differences in Interaction Patterns and Task Use

Differences were observed in how students of different academic performance levels engaged with MyBotBuddy to complete programming tasks. Lower- and medium-ability students tended to rely on the chatbot more heavily for understanding code and obtaining solutions, whereas higher-ability students used it more selectively and for extended or exploratory tasks.

Table 3 presents the types of tasks that students utilized MyBotBuddy for. Notably, for uses related to the pre-test task, many more students with lower to mid-range academic scores for the computing subject utilized MyBotBuddy to explain code or programming concepts and to obtain solutions. This may suggest that lower and medium ability students were more reliant on MyBotBuddy to facilitate their understanding of and completion of programming tasks.

4.7. Differences in Perceived Advantage of Using MyBotBuddy

Although students across all groups held positive attitudes toward using MyBotBuddy, the types of advantages they valued differed by academic performance level. Students from different academic performance levels, their attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy to learn programming were influenced by different advantages that it brought to their learning. Interestingly, only higher and medium ability students found MyBotBuddy useful for improving their programming knowledge, while lower and medium ability students cited advantages related to efficiency, facilitating revision and empowering them to become more independent in their learning. Higher and medium ability students appreciated the detailed explanations of programming concepts and functions provided by MyBotBuddy, with some suggesting that this feature makes it very suitable for learning new programming languages (P7) or new functions in Python (P17). This group of students seemed to value these advantages for the benefits of their long-term programming learning goals. The advantages that stood out to lower and medium ability students were instead related to short-term goals, such as facilitating them to complete the programming task at hand or revising functions they had already learned. Students with different grades in computing thus valued different learning advantages afforded to them by MyBotBuddy, suggesting possible differences in their primary learning goals.

4.8. Differences in Perceived Compatibility and Perceived Need

Despite having similar concerns, students of different academic performance levels expressed different sources of concern for the complexity of using MyBotBuddy. For instance, students of all ability levels faced some difficulty in understanding the responses generated by MyBotBuddy. However, only lower and medium ability students expressed concerns about the content of the generated answers being too complex, which made understanding the responses difficult for them. Higher ability students attributed this issue instead to the responses being too convoluted and cluttered with long explanations or shortcuts. The difference in concerns may imply that higher ability students pay more attention to the structure of the responses generated while assessing the complexity of the chatbot, while lower ability students assess it based on content. Almost all students who provided suggestions to change or add features to MyBotBuddy to improve their ease of use of the chatbot were low and medium ability students, which may suggest greater dissatisfaction with the complexity of using MyBotBuddy. Students from these two groups may thus also be more particular about the complexity of the educational tools they use when forming their attitudes towards using them.

Perceptions of how well MyBotBuddy aligned with students’ learning contexts were more salient among lower- and medium-ability students. Most students who highlighted the compatibility of the usage context of MyBotBuddy and their needs as the reason for its relevance to learning programming were low or medium ability students. Some of these students expressed that the fact that MyBotBuddy was specifically built for programming education purposes made the chatbot more relevant to them. These two groups of students may thus be more particular about how GenAI chatbot functions can relate to their specific learning contexts when assessing the compatibility of GenAI to their learning needs. Lastly, the concept of the perceived need to rely on MyBotBuddy to learn programming was predominantly seen in lower and medium ability students. Only low and medium ability students expressed low confidence in their programming skills while discussing their use of MyBotBuddy. In addition, it was mostly lower ability students that expressed the need to use the chatbot to make up for their weaknesses in programming. Due to their poorer academic grades in computing, lower ability students may thus feel more pressure than their peers to utilize external educational resources like GenAI to help them improve in programming. Expressions of a perceived need to rely on MyBotBuddy were predominantly found among lower-ability students, often tied to lower confidence in programming skills and pressure to improve.

In conclusion, students of varying academic performance levels in computing are receptive towards and intend to use GenAI chatbots like MyBotBuddy in their studies; however, they may differ in their specific applications of the chatbot in their learning. Students of varying academic abilities in programming also prioritized different factors when forming their attitudes towards using GenAI.

5. Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the ability of the DTPB to describe and explain secondary school students’ attitudes toward and intentions to use a GenAI chatbot, MyBotBuddy, to learn programming. It also seeks to explore any differences in students’ interactions with, attitudes towards, and intentions to use a GenAI chatbot, MyBotBuddy, to learn programming across students with varying levels of academic performance in computing.

5.1. Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions Towards Use of GenAI Tools

In relation to the first research question, the DTPB does largely accurately describe and explain the various attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy, as all the concepts theorized by

Taylor and Todd (

1995) to contribute to these attitudes have been well represented in students’ responses. Our study also found that the factors influencing Singapore secondary school students’ intentions to use MyBotBuddy differed from that theorized in the DTPB, as perceived behavioral control and subjective norms play little to no roles in influencing students’ intentions to use the chatbot. There are also some data which cannot be represented by any concepts in the framework, suggesting that the DTPB alone may be inadequate to paint a holistic picture of students’ attitudes towards and intentions to use MyBotBuddy. Our findings verified the role of students’ attitudes in shaping their intentions to use GenAI chatbots like MyBotBuddy, showing that in a high school context, attitude is still the most crucial contributing factor to behavioral intentions, as predicted in the DTPB. This finding is also seen in

Skripchuk et al. (

2024), who demonstrated how students’ intentions to use GenAI resources were primarily driven by their personal attitudes or beliefs about the outcomes of using GenAI resources. Our findings also align with the three core beliefs supporting user attitudes as theorized in the DTPB, namely relative advantage, complexity, and compatibility. In addition, it has extended the discussion on each of these three beliefs by illustrating the many specific perceptions and aspects of the user experience that students considered when constructing their beliefs about using MyBotBuddy. Hence, the present study has provided a more in-depth discussion of how attitudes towards using GenAI chatbots may influence students’ intention to use them in their studies.

5.2. Limited Roles of Perceived Behavioral Control and Subjective Norms

The constructs of perceived behavioral control and subjective norms were not observed in students’ responses on why they intended to use MyBotBuddy, which contradict the theorized relationships in the DTPB. Findings from other studies employing the DTPB to understand user intentions to adopt new technology suggest that these constructs may not always directly influence user intentions (

Shih & Fang, 2004), instead carrying indirect influence through other factors.

Hsu et al. (

2006) found that consumer intentions to use mobile text message coupons were indirectly influenced by the endorsement of their family and friends through subjective and directly influenced by consumers’ perceived behavioral control, in particular self-efficacy beliefs.

Ndubisi (

2004) demonstrates the same effect, where course leaders influenced university students’ intentions to adopt e-learning through subjective norms. Perceived behavioral control was also observed to indirectly influence the relationships between self-efficacy beliefs, experience and familiarity with e-learning, access to e-learning resources, and adoption intentions, in addition to its direct effect on adoption intentions (

Ndubisi, 2004). Given the subtle effects of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, they may thus have been overlooked by students when discussing their opinions surrounding intentions to use GenAI in favor of more salient perceptions like utility. The effects of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control may have also been overlooked given that there were no questions explicitly targeting these two perceptions. However, given the students’ status as digital natives who have grown up interacting with the world through technology (

Höfrová et al., 2024), perceived behavioral control and subjective norms may matter less in the context of their attitudes towards or intentions to use GenAI in their studies, as technology use in every aspect of one’s life is so commonplace and thus widely accepted. Students may also be extremely confident in their ability and freedom to use GenAI technology due to their familiarity with technology in general, thus diminishing the influence of perceived behavioral control on their intentions in this context. It would be interesting to explore and compare the attitudes and intentions of different age groups towards using GenAI to understand how it may be shaped by one’s native exposure or familiarity with technology.

5.3. Differences in GenAI Use Across Academic Performance Level

In relation to the second research question, the present study found differences in how students of different academic performance levels in computing chose to use MyBotBuddy to learn programming and the factors that influenced their attitudes towards the chatbot. Students in the lower and medium ability groups were more reliant on MyBotBuddy to complete programming tasks and paid more attention to their perceived need to use MyBotBuddy or its compatibility with their usage contexts in forming their attitudes towards the chatbot. Students also evaluated the advantages and complexity of using MyBotBuddy differently. For instance, higher ability students highlighted long-term advantages that MyBotBuddy could provide to their learning while lower and medium ability students pointed out how it could facilitate them with more immediate tasks like completing the task on hand. In assessing the complexity of using MyBotBuddy, lower and medium ability students also paid more attention to the complexity of the content generated while higher ability students assessed the interface of the chatbot instead. These findings contribute unique insights into how individual factors, such as academic ability, may be associated with differences in high school students’ exact priorities and considerations when evaluating and making decisions on whether to use GenAI chatbots in their studies. This discovery opens new doors into research on exploring the factors causing these differences in perceptions and use of GenAI amongst students of varying levels of academic ability.

5.4. Perceived Need as a New Influencing Factor

Interestingly, this study’s findings also introduced a new construct previously unseen in the DTPB, which is students’ perceived need to use GenAI models in their studies. Students who felt that it was necessary for them to use GenAI chatbots due to their poor programming skills carried both positive attitudes towards using MyBotBuddy and intended to continue using the chatbot. This concept and its associated beliefs may be explained by the expectancy-value theory of motivation (

Eccles et al., 1983). This theoretical model posits that students’ motivation to pursue an activity is influenced by their expectations of successfully completing the activity and the subjective value of the task in terms of weighing its usefulness, costs, possible incentives, and importance to their own goals. Expectancy of success and subjective task value are in turn influenced by other factors such as cultural influences, students’ past experiences with the activity or similar activities, and students’ self-belief.

Eccles et al. (

1983) posits that students are more motivated to pursue tasks that they value more and expect to succeed in. In the present study, participants highlighted how their low confidence in their programming skills fueled their intentions to use GenAI tools like MyBotBuddy as they felt that they needed to rely on its assistance to complete programming tasks and overcome their weaknesses while programming. These students thus demonstrate negative self-beliefs about their programming ability, but a high expectancy for success in learning programming when they use GenAI tools. Students also valued MyBotBuddy for its usefulness in helping them to address their weaknesses while programming, suggesting a high subjective task value of using GenAI tools to learn. This combination of beliefs thus led students to perceive a need to use GenAI tools like MyBotBuddy to learn programming, supporting their motivation to use MyBotBuddy. The expectancy-value theory of motivation (

Eccles et al., 1983) may thus explain the perceived need that students feel to rely on GenAI when learning programming. The present study’s findings demonstrate how specific user beliefs about themselves, such as confidence in their programming abilities, can interact with their beliefs about technology, like the relative advantages gained by using GenAI tools, to influence their attitudes towards using GenAI through creating a perceived need to use it. Future research could be performed to specifically explore how self-belief, such as level of perceived competence, interacts with the constructs in the DTPB to shape user attitudes and use patterns. For high school contexts, frameworks guiding AI adoption in education should therefore include perceived necessity as a construct, particularly for skill-based subjects such as programming.

5.5. Implications for GenAI Integration in High School Computing

This study’s findings present several practical applications for educators or educational institutions seeking to guide or support GenAI use in high schools. The findings recommend that high schools seeking to integrate GenAI into their curriculum should focus on attitude-building strategies and on embedding GenAI use into core learning activities to encourage adoption and acceptance of this technology. As attitude may be the strongest predictor of students’ intentions to use MyBotBuddy, it may thus be crucial for students’ early interactions with such tools to be positive, engaging, and clearly beneficial to their learning to foster positive attitudes towards GenAI use in their studies. Including activities that showcase both the immediate usefulness of GenAI in helping students complete the task at hand with more efficiency or ease, as well as the long-term benefits to their problem-solving abilities, when introducing GenAI use in the classroom may thus strengthen students’ willingness to use it in their own studies. In addition, the findings from this study suggest that perceived behavioral control and subjective norms play a minor role in influencing intentions to use GenAI in their studies. When integrating GenAI, programs ought to focus less on persuading students through peer influence or confidence building, but instead on helping them to discover concrete benefits in authentic learning contexts. Hence, it may also be useful if GenAI tools are embedded into essential coursework or students’ existing online learning platforms. This may improve the perceived necessity of GenAI to students as well as allow students more interaction opportunities with GenAI, making its value to their studies more salient. Students may thus be better able to recognize the usefulness and relevance of GenAI to their studies, encouraging positive attitudes towards adopting it.

The present study also provides some suggestions for educators’ instructional strategies when integrating GenAI into their practice. The study showed how students of varying academic abilities may differ in their values and preferences while using GenAI educational tools. While lower- and medium-ability students may benefit more from features or activities that reduce content complexity and directly assist them in completing a task, higher ability students value opportunities for extended learning, more complex problem solving, and efficient navigation. To match students’ different needs and preferences, teachers can adapt instructional strategies to offer different levels of guidance to each student, such as through assigning different levels of task complexity to each student. More advanced students could be offered opportunities for independent exploration or be assigned more complex application-related programming tasks while interacting with GenAI, while students who need more support could receive more hands-on guidance from their teachers while using GenAI. Students who need more support could also be assigned to work together with GenAI to complete tasks where GenAI could support their weaknesses in programming or use GenAI as a platform on which to practice programming and revise their existing classroom content.