A Participatory Workshop Design for Engaging Young People in IT Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Pedagogical Framework

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development Competencies

- Systems thinking competence: understanding and analyzing complex systems, their interdependencies, and feedback loops.

- Anticipatory competence: envisioning and evaluating multiple future scenarios, including risks and uncertainties.

- Normative competence: understanding and reflecting on values, principles, and goals for sustainable development.

- Strategic competence: designing and implementing effective actions toward sustainability.

- Collaboration competence: learning and working with others across cultures and disciplines.

- Critical thinking competence: questioning assumptions, norms, and opinions in sustainability debates.

- Self-awareness competence: reflecting on one’s values, motivations, and role in sustainability contexts.

- Integrated problem-solving: combining and applying different competencies to address complex sustainability challenges.

- Design thinking (Macagno et al., 2024): fosters creativity, prototyping, and innovation and is crucial in the context of digital sustainability and product design.

- Eco-digital literacy (Salto Youth, 2024): an emerging term promoting a critical understanding of how digital solutions are designed, operated, and embedded in broader sustainability challenges.

2.2. Core Pedagogical Approaches in ESD

| Approach | Key Characteristics | Relevance to ESD | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformative Learning | Critical reflection; change in worldview; confronting assumptions | Promotes deep shifts in learners’ perspectives to support sustainability-oriented mindsets | (Macagno et al., 2024; Mezirow, 1997; Nicholson et al., 2024; Sterling, 2010b; Trevisan et al., 2022) |

| Experiential Education | Learning through direct experience; action-reflection cycles | Builds learner engagement with sustainability through real-world, hands-on contexts | (Gattinoni et al., 2025; Kolb, 2014; Sipos et al., 2008; Van Gerven, 2024) |

| Participatory Design/Co-Design | Learners as co-creators of knowledge; shared authorship; often community-oriented | Encourages democratic and collaborative exploration of sustainability issues | (Brandau & Alirezabeigi, 2023; Poirier, 2009; Stavholm et al., 2024; Vyas et al., 2023) |

| Problem-Based Learning (PBL) | Solving open-ended, real-life problems; learner-driven investigation | Supports systems thinking and interdisciplinary understanding | (Bessant et al., 2013; Cavadas & Linhares, 2022; d’Escoffier et al., 2024; Lamere et al., 2024; Llach & Bastida, 2023) |

| Pedagogical Approach/ ESD Competence | Transformative Learning | Experiential Learning | Participatory Design/Co-Design | Problem-Based Learning | ProS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems thinking | + | + − | + | + | + |

| Anticipatory competence | + | + − | + − | + | + |

| Normative competence | + | + − | + | + − | + − |

| Strategic competence | + − | + − | + | + | + − |

| Collaboration competence | + − | + | + | + | + |

| Critical thinking | + | + − | + | + | + |

| Self-awareness | + | + | + − | + − | + − |

| Integrated problem-solving | + − | + − | + | + | + |

| Design thinking (extension) | − | − | + − | + − | + |

| Eco-digital literacy (extension) | − | − | − | − | + |

2.3. Positioning Within Sustainability-Oriented Educational Design Approaches

3. Workshop Design and Methodology

3.1. Target Group and Objectives

- Awareness building: Raise critical awareness about the environmental, economic, and social impacts of digital technologies, particularly focusing on the life cycle of IT products and their broader implications in all three sustainability dimensions.

- Competence development: Equip participants with sustainability-oriented design and decision-making competencies to develop sustainable IT solutions. This involves systems thinking, creativity, and reflective judgement, enabling learners to balance user needs with sustainability principles in environmental protection, social responsibility, and economic viability.

- Empowerment and agency: Encourage learners to act as capable contributors to sustainability challenges by engaging in authentic design tasks, fostering self-efficacy and participatory attitudes.

- Knowledge documentation: Systematically collect young people perspectives on sustainable digital futures to inform educational research and policymaking, thus bridging the gap between learner experience and societal discourse on sustainability.

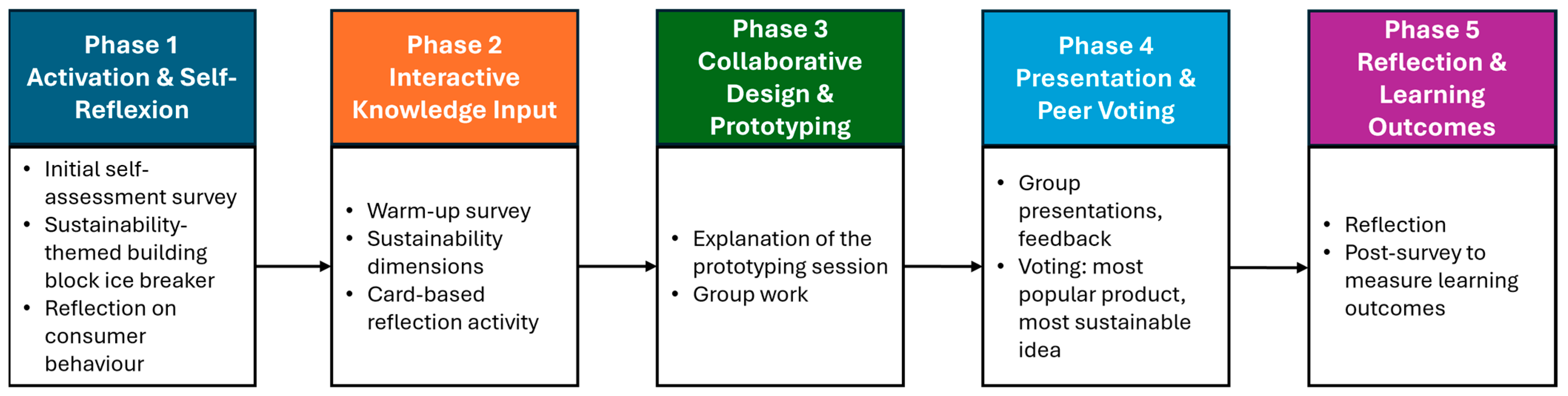

3.2. Workshop Structure, Learning Phases and Competence Development

3.2.1. Phase 1—Activation and Self-Reflection

3.2.2. Phase 2—Interactive Knowledge Input

3.2.3. Phase 3—Collaborative Design and Prototyping

3.2.4. Phase 4—Presentation and Peer Voting

3.2.5. Phase 5—Reflection and Measurement of Learning Outcomes

3.3. Materials and Instructional Media

- Building blocks and building guides: Used in phase 1 to visually and physically represent sustainability impacts, enhancing engagement and comprehension through multisensory learning.

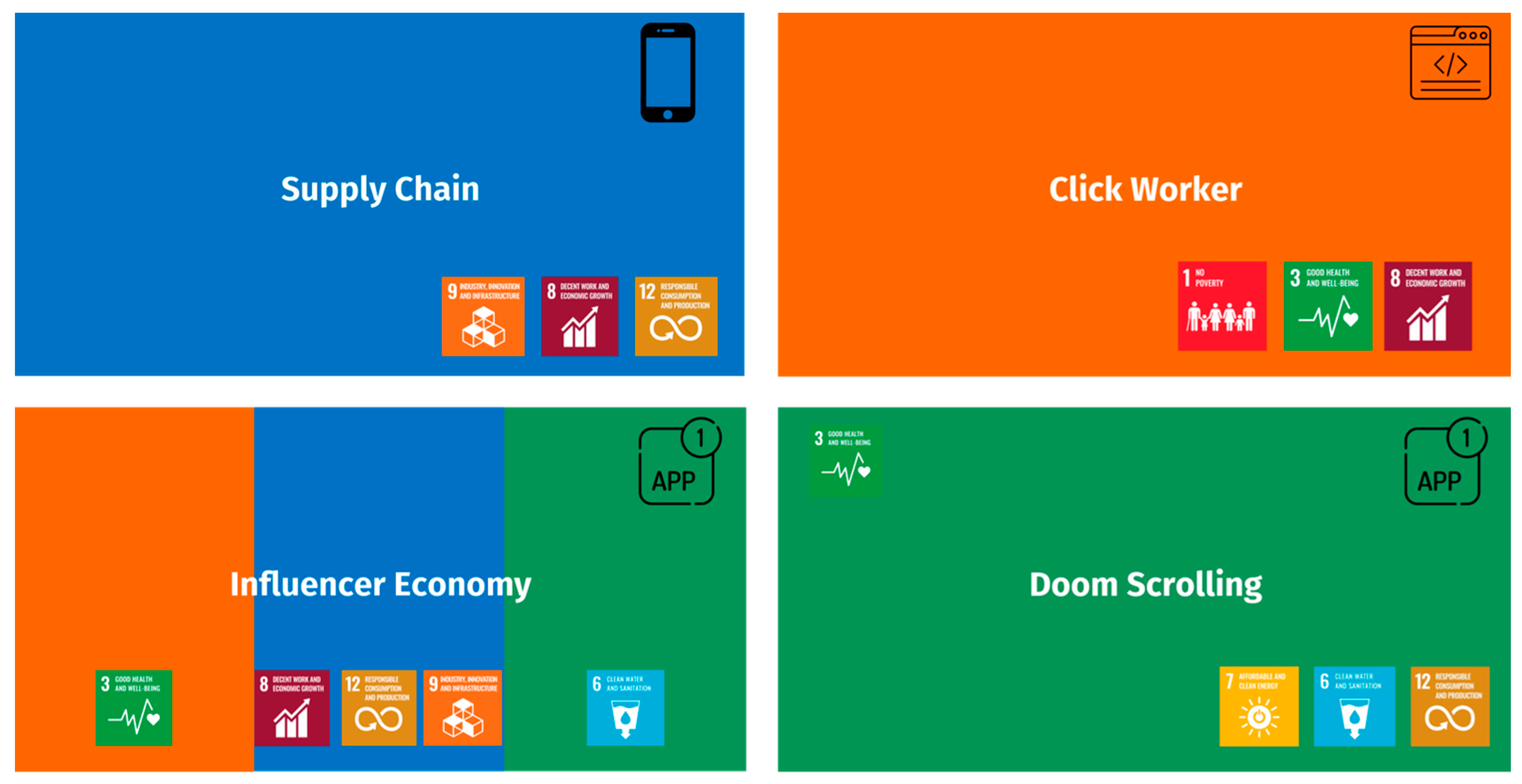

- Sustainability card sets and explanatory slides: Used in phase 2 to transmit knowledge regarding key terms, concepts, and negative effects related to IT and sustainability, facilitating gamified and collaborative knowledge acquisition.

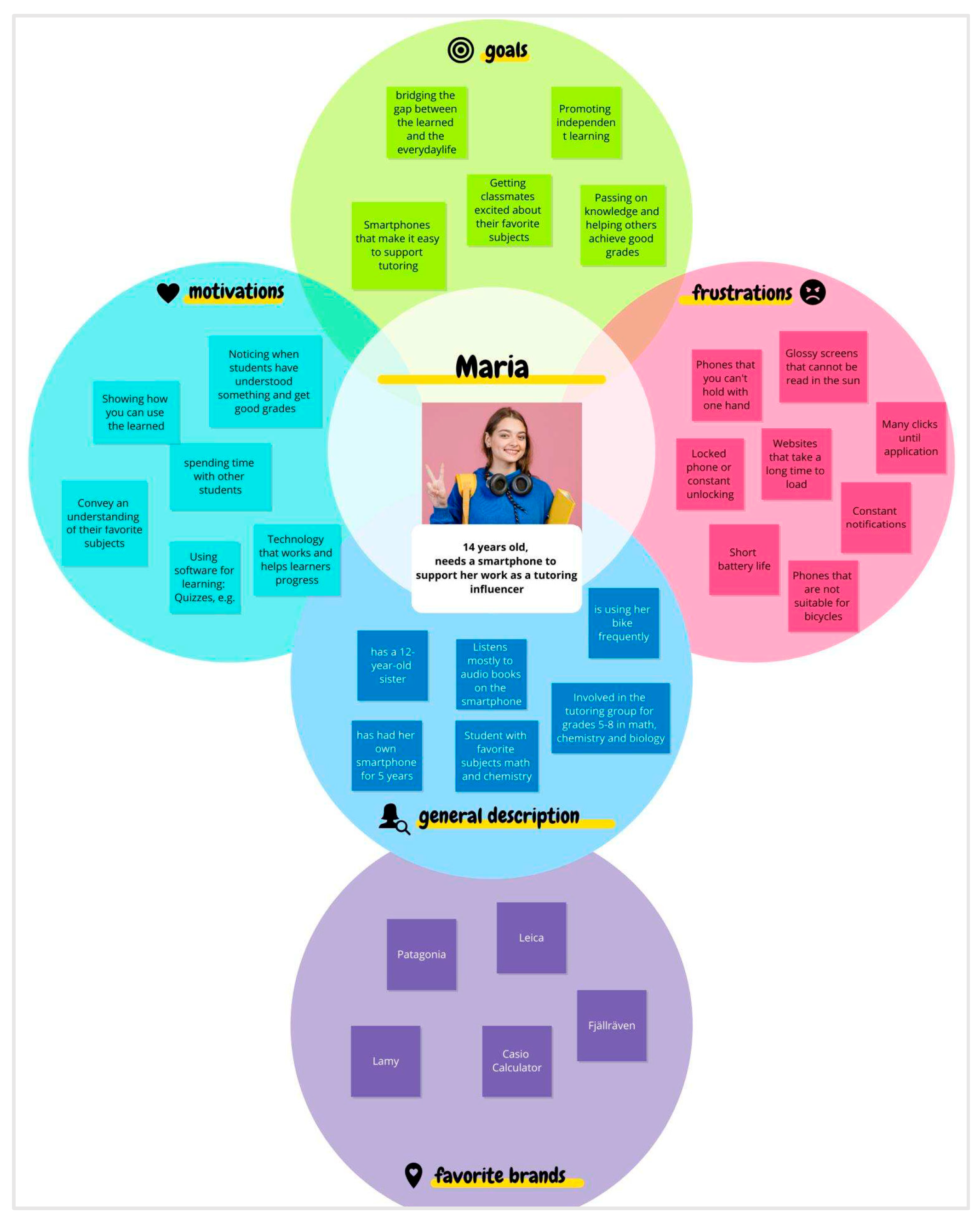

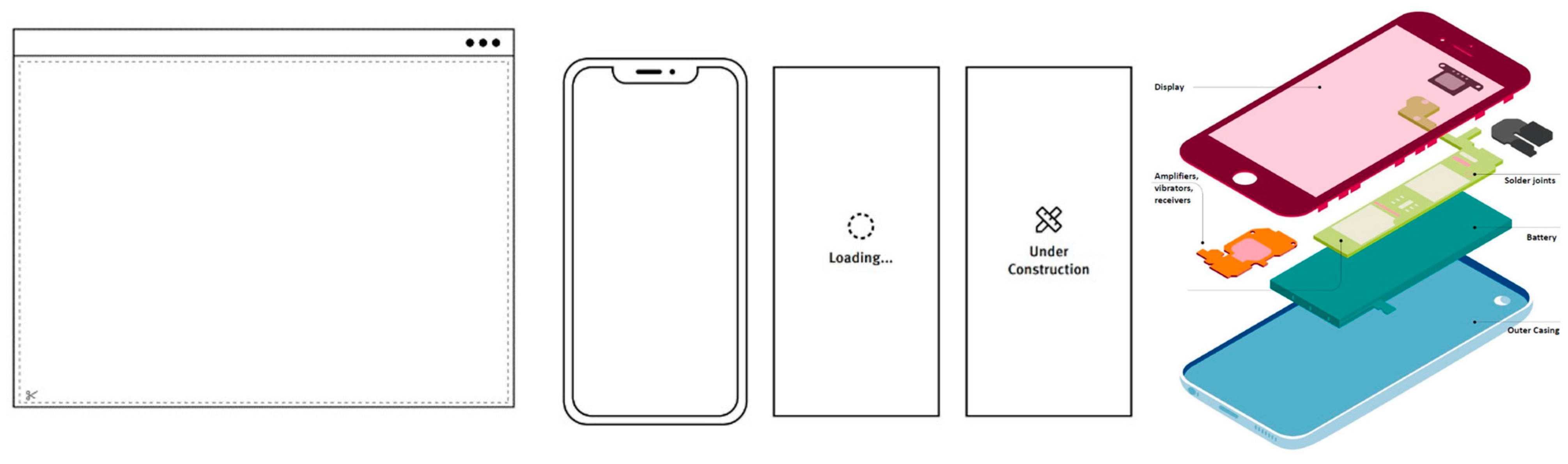

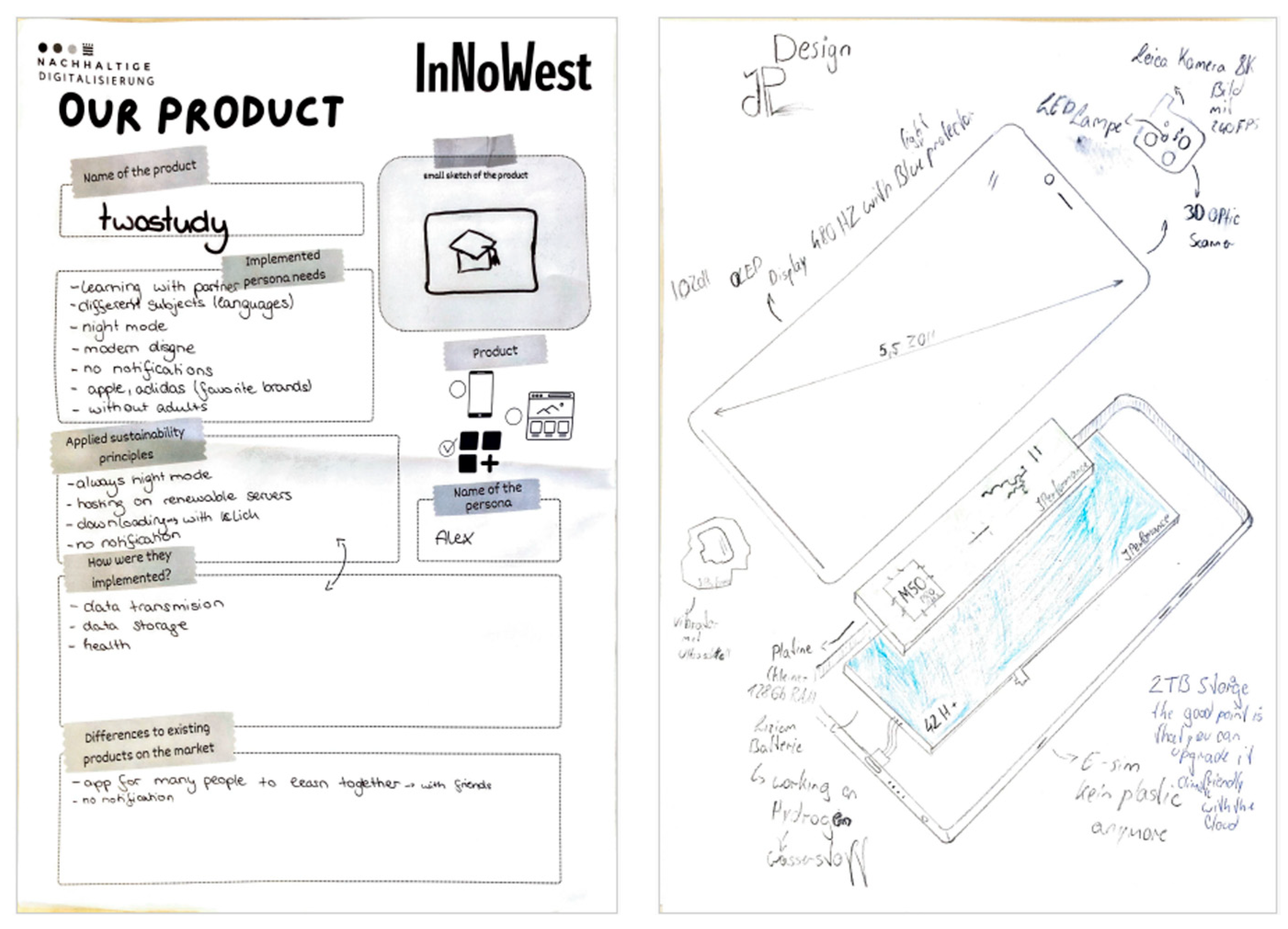

- User personas and cut-out kits: Used in phase 3 to enable empathetic, user-focused design work, encouraging learners to ground their paper-based prototypes in authentic contexts. Cut-out kits are used to trigger visual and tactile thinking supporting low-threshold prototyping, collaborative ideation, and reusability.

- Sustainability catalogues: Used in phase 3, structured sustainability criteria assist participants in critically analyzing paper-based prototypes along environmental, economic, and social lines.

- Surveys: Administered pre- and post-workshop surveys are used to capture learner knowledge, attitudes, and reflections on sustainable IT as well as related possible changes in the attitudes after the workshop.

3.4. Instructional Approach and Facilitation

3.5. Adaptability and Transferability

4. Implementation

4.1. Workshop Delivery and Facilitation

4.2. Learning Environment and Resources

4.3. Data Collection and Outcome Measurement

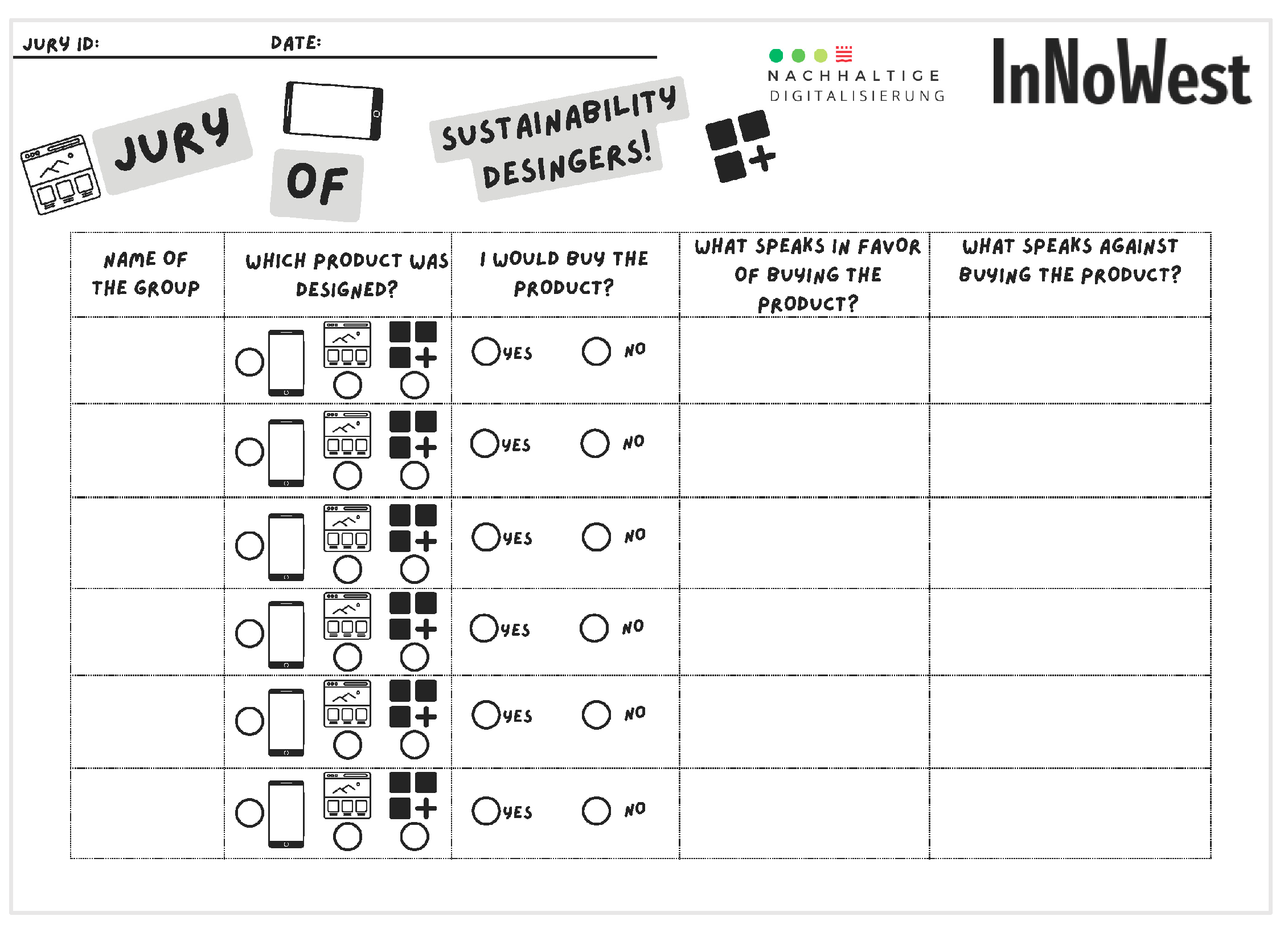

- Peer voting templates: During the peer evaluation phase, participants use structured templates to assess group paper-based prototypes based on sustainability criteria, user relevance, and creativity. These evaluations provide valuable data on learners’ ability to critically appraise sustainable IT designs, reflecting their understanding and application of key concepts.

- Presentation templates: Groups prepare presentations of their paper-based prototypes guided by standardized templates that prompt explanation of design choices, sustainability considerations, and user-centred features. The content and quality of these presentations serve as indicators of participants’ communication skills, depth of reflection, and conceptual grasp.

- Cut-out kits: The paper-based prototypes created using cut-out kits and other materials constitute tangible evidence of learners’ design competencies and creativity. Analysis of these artefacts, including documentation of design rationales, offers insights into learners’ problem-solving processes and integration of sustainability principles.

5. Discussion

5.1. Educational Implications

5.2. Sustainability Implications

5.3. Challenges and Limitations

5.4. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | German version: “Prototyping Sustainability–nachhaltige IT gestalten”. |

| 2 | https://www.canva.com/ (accessed on 28 September 2025). |

| 3 | https://innowest-brandenburg.de/ (accessed on 28 September 2025). |

References

- Ahmad, N., Toro-Troconis, M., Ibahrine, M., Armour, R., Tait, V., Reedy, K., Malevicius, R., Dale, V., Tasler, N., & Inzolia, Y. (2023). CoDesignS education for sustainable development: A framework for embedding education for sustainable development in curriculum design. Sustainability, 15(23), 16460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, V. (2023). Equity and access in digital education: Bridging the divide. In Contemporary challenges in education: Digitalization, methodology, and management (pp. 45–59). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albar, R., Gauthier, A., & Vasalou, A. (2024, June 17–20). A playful path to sustainability: Synthesizing design strategies for children’s environmental sustainability learning through gameful interventions. The 23rd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference (pp. 201–217), Delft, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrae, A. S. G. (2018). Collection rate and reliability are the main sustainability determinants of current fast-paced, small, and short-lived ICT products. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development, 14, 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M., & Michelsen, G. (2011). Learning for change: An educational contribution to sustainability science. Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2128421 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83(2), 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belland, B. R. (2017). Instructional scaffolding in STEM education. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernert, P., Wanner, M., Fischer, N., & Barth, M. (2025). Design principles for advancing higher education sustainability learning through transformative research. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(9), 20581–20598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessant, S., Bailey, P., Robinson, Z., Tomkinson, C. B., Tomkinson, R., Ormerod, R. M., & Boast, R. (2013). Problem-based learning: A case study of sustainability education. Higher Education Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2015). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Sampson, J. (2001). Peer learning in higher education: Learning from and with each other. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, H. (2015). The SAGE handbook of action research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Brandau, N., & Alirezabeigi, S. (2023). Critical and participatory design in-between the tensions of daily schooling: Working towards sustainable and reflective digital school development. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(2), 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. HarperBusiness. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadas, B., & Linhares, E. (2022). Using a problem-based learning approach to develop sustainability competencies in higher education students. In Handbook of sustainability science in the future (pp. 1–28). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CELI. (2024, December 16). The hidden environmental cost of data center growth—Millions of tons of e-waste. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@celions/the-hidden-environmental-cost-of-data-center-growth-millions-of-tons-of-e-waste-0bb4a18dbaa1 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Coburn, C. E. (2003). Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educational Researcher, 32(6), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codding, D., Yen, A. H., Lewis, H., Johnson-Ojeda, V., Frey, R. F., Hokanson, S. C., & Goldberg, B. B. (2024). Nationwide inclusive facilitator training: Mindsets, practices and growth. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 43(2), 161–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(4), 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dede, C. (2006). Online professional development for teachers: Emerging models and methods. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- d’Escoffier, L. N., Guerra, A., & Braga, M. (2024). Problem-based learning and engineering education for sustainability: Where we are and where could we go? Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education, 12(1), 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September 28–30). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. The 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (pp. 9–15), Tampere, Finland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichev, C., & Dicheva, D. (2017). Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drljić, K., Čotar Konrad, S., Rutar, S., & Štemberger, T. (2025). Digital equity and sustainability in higher education. Sustainability, 17(5), 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhacham, E., Ben-Uri, L., Grozovski, J., Bar-On, Y. M., & Milo, R. (2020). Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature, 588(7838), 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falchikov, N., & Goldfinch, J. (2000). Student peer assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, B. J., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A.-R., Cheng, B. H., & Sabelli, N. (2013). Design-based implementation research: An emerging model for transforming the relationship of research and practice. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 112(2), 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1978). Pedagogy of the oppressed*. In Toward a sociology of education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change (5th ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, A., García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso, A., Casillas-Martín, S., & Cabezas-González, M. (2023). Sustainability in digital education: A systematic review of innovative proposals. Education Sciences, 13(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, P., Molinari, D., Pampanin, M., Porta, G. M., & Raimondi, A. (2025). DICA4Schools: Good practices of the role of academy in education for sustainability. Journal of Sustainability Education, 31. Available online: https://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/dica4schools-good-practices-of-the-role-of-academy-in-education-for-sustainability_2025_05/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Giannini, S. (2025). Bridging the digital and green transitions through education. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/bridging-digital-and-green-transitions-through-education (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Goel, A., Masurkar, S., & Pathade, G. R. (2024). An overview of digital transformation and environmental sustainability: Threats, opportunities, and solutions. Sustainability, 16(24), 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintemann, R., & Hinterholzer, S. (2020). Rechenzentren in Europa—Chancen für eine nachhaltige digitalisierung (Teil 1). Borderstep Inatitut. Available online: https://www.borderstep.de/publikation/hintemann-r-hinterholzer-s-2020-rechenzentren-in-europa-chancen-fuer-eine-nachhaltige-digitalisierung-berlin-borderstep-institut/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hmelo-Silver, C., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2007). Scaffolding and Achievement in problem-based and inquiry learning: A response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006). Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, N. M., & Biswas, G. (2024). Co-designing teacher support technology for problem-based learning in middle school science. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(3), 802–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. B., & Schnack, K. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 3(2), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A. K., Rana, S., Singh, M., & Upadhyaya, S. (2025). Influence of digital platforms on consumer behavior. In Sustainability, innovation, and consumer preference (pp. 161–196). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jickling, B., & Sterling, S. (2017). Post-sustainability and environmental education: Remaking education for the future. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M. E., Kleinsasser, R. C., & Roe, M. F. (2014). Wicked problems: Inescapable wickedity. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(4), 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, Q. (2024). To have or to be—Reimagining the focus of education for sustainable development. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 56(4), 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey, G. (2020). Facilitating group learning: Strategies for success with diverse learners. PM Press/Reach and Teach. Available online: https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=1138 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Lamere, M., Leon, M., Fowles-Sweet, W., Yeomans, L., & Fogg-Rogers, L. (2024). Using problem- and project-based learning to integrate sustainability in engineering education. Engineering Professors Council. Available online: https://epc.ac.uk/toolkit/using-problem-and-project-based-learning-to-integrate-sustainability-in-engineering-education/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Lee, G. K. S. (2025). Embedding sustainability in higher education: A review of institutional strategy, curriculum reform, and digital integration. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 15(2), 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A., Heiss, J., & Byun, W. J. (2018). Issues and trends in education for sustainable development. UNESCO Publishing. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261954 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Liedtka, J. (2018). Why design thinking works. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/09/why-design-thinking-works (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Lim, C. K., Haufiku, M. S., Tan, K. L., Farid Ahmed, M., & Ng, T. F. (2022). Systematic review of education sustainable development in higher education institutions. Sustainability, 14(20), 13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llach, M. C., & Bastida, M. L. (2023). Exploring innovative strategies in problem based learning to contribute to sustainable development: A case study. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(9), 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macagno, T., Nguyen-Quoc, A., & Jarvis, S. P. (2024). Nurturing sustainability changemakers through transformative learning using design thinking: Evidence from an exploratory qualitative study. Sustainability, 16(3), 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorry, S. (2025, August 19). The roadmap to sustainable IT. TechRadar. Available online: https://www.techradar.com/pro/the-roadmap-to-sustainable-it (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED505824 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Mercer, N., & Howe, C. (2012). Explaining the dialogic processes of teaching and learning: The value and potential of sociocultural theory. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, T., Vargas, V. R., Price, E. A. C., Himatlal, K., Campen, L., Hartley, M., & Hewitt, T. (2024). Transformative learning design for ESD in a skills-based module. Open Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obringer, R., Rachunok, B., Maia-Silva, D., Arbabzadeh, M., Nateghi, R., & Madani, K. (2021). The overlooked environmental footprint of increasing Internet use. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 167, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). Measuring the environmental impacts of artificial intelligence compute and applications. OECD Digital Economy Papers. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/measuring-the-environmental-impacts-of-artificial-intelligence-compute-and-applications_7babf571-en.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Cheng, B. H., & Sabelli, N. (2011). Organizing research and development at the intersection of learning, implementation, and design. Educational Researcher, 40(7), 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, R., & Gallagher, L. P. (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 921–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, M. (2009). Participatory workshops: Hands-on planning for sustainable schools. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1993/3102 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Rieckmann, M. (2018). Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in education for sustainable development. In Issues and trends in education for sustainable development (pp. 39–59). UNESCO Publishing. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261802 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Riess, W., Martin, M., Mischo, C., Kotthoff, H.-G., & Waltner, E.-M. (2022). How can education for sustainable development (ESD) be effectively implemented in teaching and learning? An analysis of educational science recommendations of methods and procedures to promote ESD goals. Sustainability, 14(7), 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, A. (2022, February 7). Global supply chains must get smart–and sustainable. Wired. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/global-supply-chains-smart-sustainable/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ryan, A., Morel, C., Goodman, J., Hermes, J., Rehman, M. A., Louche, C., Keranen, A., & Juntunen, M. (2025). Learning to learn differently: Studio-based education for responsible management. The International Journal of Management Education, 23(3), 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salto Youth. (2024). Eco-digital literacy and citizenship for our planet & future (Digital waste). Available online: https://www.salto-youth.net/tools/otlas-partner-finding/project/eco-digital-literacy-and-citizenship-for-our-planet-future-digital-waste.15424/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Sá, P., Silva, P. C., Peixinho, J., Figueiras, A., & Rodrigues, A. V. (2023). Sustainability at play: Educational design research for the development of a digital educational resource for primary education. Social Sciences, 12(7), 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. (2021). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos, Y., Battisti, B., & Grimm, K. (2008). Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(1), 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. P. (2012). Data in practice: Conceptualizing the data-based decision-making phenomena. American Journal of Education, 118(2), 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavholm, E., Mackley, H., Caughey, J., Heard, A., & Edwards, S. (2024). Co-design with children, families, and educators for understanding children’s digital life-worlds for play and learning. CoDesign, 21(3), 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. (2010a). Learning for resilience, or the resilient learner? Towards a necessary reconciliation in a paradigm of sustainable education. Environmental Education Research, 16(5–6), 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. (2010b). Transformative learning and sustainability: Sketching the conceptual ground. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Switzer, S., Alarcón, A. V., Gaztambide-Fernández, R., Burkholder, C., Howley, E., & Carrasco, F. I. (2024). Online and remote community-engaged facilitation: Pedagogical and ethical considerations and commitments. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 5(3), 116337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternès, A. (2019). Nachhaltigkeit und digitalisierung als chance für unternehmen. In M. Englert, & A. Ternès (Eds.), Nachhaltiges management: Nachhaltigkeit als exzellenten managementansatz entwickeln (pp. 79–104). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TINKERING for Sustainability at School. (2024). Available online: https://tinkeringschool.eu/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Tobel, I. (2024). The role of digital education in achieving sustainable green campuses. Journal of Applied Technical and Educational Sciences, 14(1), 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, L. V., Mello, S., Pedrozo, E., & da Silva, T. N. (2022). Transformative learning for sustainability practices in management and education for sustainable development: A meta-synthesis. Environmental & Social Management Journal, 16(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2005). Guidelines and recommendations for reorienting teacher education to address sustainability. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000143370 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- UNESCO. (2009). UNESCO world conference on education for sustainable development. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000188799 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- UNESCO. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- UNESCO. (2020). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=fr (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- UN Trade & Development. (2024). Digital economy report 2024. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/der2024_en.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Vaishnav, D. (2024). Leveraging digital transformation for sustainable development. California Management Review Insights. Available online: https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2024/07/leveraging-digital-transformation-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Van Gerven, J. P. (2024). Potentials for critical, community engaged place-based experiential learning: Using a campus farm to integrate the environmental studies curriculum. Journal of Sustainability Education, 30. Available online: https://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/potentials-for-critical-community-engaged-place-based-experiential-learning-using-a-campus-farm-to-integrate-the-environmental-studies-curriculum_2024_12/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Vasalou, A., & Gauthier, A. (2023). The role of CCI in supporting children’s engagement with environmental sustainability at a time of climate crisis. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 38, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D., Khan, A. H., & Cooper, A. (2023, April 23–28). Democratizing making: Scaffolding participation using e-waste to engage under-resourced communities in technology design. The 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–16), Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A. E. J. (2015). Beyond unreasonable doubt. Education and learning for socio-ecological sustainability in the Anthropocene. Wageningen University. Available online: https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/beyond-unreasonable-doubt-education-and-learning-for-socio-ecolog (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorman, H. (2024, October 14). The environmental impact of data centers—Concerns and solutions to become greener. Park Place Technologies. Available online: https://www.parkplacetechnologies.com/blog/environmental-impact-data-centers/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levina, O.; Lindauer, F.; Revina, A. A Participatory Workshop Design for Engaging Young People in IT Sustainability. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121570

Levina O, Lindauer F, Revina A. A Participatory Workshop Design for Engaging Young People in IT Sustainability. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121570

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevina, Olga, Friederike Lindauer, and Aleksandra Revina. 2025. "A Participatory Workshop Design for Engaging Young People in IT Sustainability" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121570

APA StyleLevina, O., Lindauer, F., & Revina, A. (2025). A Participatory Workshop Design for Engaging Young People in IT Sustainability. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121570