1. Introduction

The term “assessment” originated from the Latin word

assidere—“to sit beside,” referring to a teacher sitting with their students to ascertain how to best support them on their learning journey. It indicates a close relationship and a sharing of experience. However, while many assessments have “good intentions” to measure student learning and inform instruction, they are often designed from a monoglossic, deficit-oriented orientations. Such assessments function as dismissive of multilingual students’ cultural and linguistic funds of knowledge which serves to maintain power structures that privilege standardized and national languages. As a result, these practices, often in conjunction with other structural and political forces (e.g., restrictive language-in-education policies), have exacerbated existing inequities and further contributed to the historic, systemic marginalization of language-minoritized multilinguals (

Schissel, 2019). Indeed, assessment practitioners have only more recently begun to take seriously the task of meaningful inclusion of test-takers’ linguistic diversity in assessment development processes (

Schissel, 2025).

The struggles in the field of assessment to cultivate dynamic environments with inclusive are rooted in monoglossic language ideologies. Monoglossic language ideologies are invested in the oppression of linguistic diversity, the promotion of linguistic purism, and the maintenance of power structures that privilege particular language varieties (e.g., standard languages, national languages;

García & Li, 2014). Such ideologies are found in other areas of education as well. Language education policies about the medium of instruction across different areas of the world have often enforced strict separation of languages during instruction. In dual language bilingual education programs in the United States, a certain percentage of the instruction is often mandated in a specific language per day or in postcolonial contexts such as South Africa, instruction transitions from English as a subject to English as the medium of instruction for all subjects at grade 4.

Contrasting monoglossic perspectives are heteroglossic language ideologies that cultivate spaces for linguistic diversity to thrive, often in opposition to existing power structures. Building on this orientation, researchers and educators seeking equitable and just assessments that center the voices of multilingual test-takers, especially those from marginalized communities (

Gorter & Cenoz, 2017;

Shohamy, 2011), have turned to a growing area of scholarship that uses an asset-based, heteroglossic perspective:

translanguaging. Translanguaging research has expanded exponentially across global educational contexts, highlighting its theoretical, pedagogical, and increasingly epistemological potential to challenge dominant monolingual ideologies and redefine what counts as legitimate knowledge and participation in education, with important implications for assessment (

García & Kleyn, 2016;

Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025;

Zheng & Qiu, 2024).

As assessment practices across the world have begun to integrate translanguaging rooted in heteroglossia and social justice (

Seltzer & Schissel, 2025;

Van Viegen et al., in press), we found it timely to conduct an analysis of the available research in this area. Assessment approaches that use translanguaging, we posit, may represent some of the first meaningful and affirming understandings of linguistic diversity within assessments--combating decades of modern practices that have been marginalizing and discriminatory.

Our literature review of empirical studies of translanguaging and assessment provides an overview and synthesis of the impact and implications of this new area of research. Our paper focuses on the following two research questions: (1) What is the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research? and (2) What are the affordances and challenges of translanguaging within assessments? In this paper, we begin by detailing the theory of languaging with respect to translanguaging that we used to identify studies for this literature review. We then provide an overview of our methods and procedures for the literature review before reporting our findings with respect to our research questions. We conclude with a discussion of the past, present, and potential future implications of this scholarship.

2. Conceptual Framework

Translanguaging represents a paradigmatic shift in how language is conceptualized and how multilingual students are supported in educational contexts, including assessment. Traditionally, assessments have been designed from monoglossic perspectives, which treat languages as discrete, bounded systems and privilege standardized national languages as the default medium of evaluation (

Shohamy, 2011). Such approaches can systematically disadvantage language-minoritized students by invalidating their full linguistic repertoires and reinforcing linguistic hierarchies tied to colonial and modernist-era structuralist ideologies (

Makoni & Pennycook, 2007). Adopting a

Rawlsian (

2001) justice-as-fairness lens, we view language background as social difference rather than as a barrier; accordingly, fair assessment practices must not conflate evidence of learning with conformity to a single standardized code. While this Rawlsian orientation underscores fairness and access, we also acknowledge that educational justice extends beyond procedural equity. Translanguaging assessment must engage broader dimensions of justice—including recognition, representation, and epistemic transformation (

Fraser, 2009;

García & Leiva, 2014;

Heugh et al., 2017)—to fully capture the relational, cultural, and, structural dimensions of equity in multilingual education.

As a theory, translanguaging provides a heteroglossic, more socially just alternative, recognizing the fluid and dynamic nature of multilingual speakers’ language practices. Grounded in Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia, translanguaging posits that multilingual individuals do not operate within separate, compartmentalized linguistic codes but rather draw upon an integrated linguistic and semiotic repertoire (

García & Li, 2014). For language-minoritized students especially, this means that translanguaging is not just about using multiple named languages but about asserting their epistemologies, identities, and ways of knowing in educational spaces where their linguistic resources have historically been marginalized (

Arias & Schissel, 2021).

As a pedagogical approach, translanguaging leverages students’ full linguistic, cultural, and semiotic repertoires to facilitate meaningful learning (

Li & García, 2022). Rather than tokenistically including home languages, it repositions multilingual students as knowledge producers, challenging deficit discourses that frame them as linguistically incomplete, in need of remediation, or languageless (

Rosa, 2019). This shift is particularly crucial in assessment, a historically exclusionary space where multilingual students have been forced to conform to standardized linguistic norms that ignore their lived communicative practices (

Sánchez, 1934;

Schissel, 2019). By disrupting these paradigms, translanguaging offers a critical intervention in rethinking assessment as a more just and inclusive practice (

García & Leiva, 2014). It has the potential to decolonize educational evaluation by challenging the dominance of monolingual, standardized measures of achievement and instead recognizing the full range of multilingual students’ meaning-making abilities, viewing multilingualism as the essence of validity for assessments (

Schissel, 2019).

García and Kleyn (

2016) argue that translanguaging “enables a more socially just and equitable education for bilingual students” (p. 17). Integrating translanguaging into assessment design allows educators and researchers to reclaim assessment as a tool for equity rather than exclusion—one that, as its Latin root suggests, truly “sits with” students to support their learning.

As assessment practices worldwide increasingly incorporate translanguaging, a systematic review of existing research is both timely and necessary. While translanguaging has been widely explored in pedagogy (

Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025), its application in assessment remains understudied, particularly in terms of its interaction with educational equity. Our review examines the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research as well as the affordances and challenges of its integration. This synthesis aims to highlight sustainable practices, identify gaps, and contribute to ongoing conversations about reimagining assessment as a more inclusive and socially just process.

3. Methods

Zhongfeng and Jamie began the process for the systematic review by reviewing the guidance from

Newman and Gough (

2020) on systematic literature reviews in education and APA style JARS for inclusion criteria for qualitative research (

American Psychological Association, 2023) to design our systematic review of research published on translanguaging and assessment. Newman and Gough recommend

Developing a research question

Designing a conceptual framework

Constructing selection criteria

Developing search strategies

Selecting studies using the selection criteria

Coding studies

Assessing the quality of the studies

Synthesizing study results to answer research questions

Reporting findings (p. 6)

We closely followed this process and divided tasks among the research team. Zhongfeng coordinated the process. Zhongfeng and Jamie led steps 1–4 and Chia-Hsin and Jessica worked closely on steps 4–6. All members of the research team collectively contributed to steps 7–9. We detail the process below.

Guided by Zhongfeng and Jamie, Jessica began our systematic review of the intersection of translanguaging and assessment by engaging in a comprehensive search across two databases: Google Scholar and ERIC. These databases were chosen as they are widely known for capturing a broad spectrum of peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, particularly those related to education.

Table 1 shows the original number of results from searching each database.

From these original 1056 results, Jessica excluded all items that did not fit the following criteria: empirical; journal article or book chapter published between 2012 and 2023 (the year in which our search was conducted); aligned with a heteroglossic theory of language; peer reviewed. Additionally, we excluded items that did not align with a heteroglossic and social justice-oriented approach to translanguaging. The team discussed any questions about inclusion based on this specific criterion until reaching consensus.

1 For example, we excluded an article that discussed multilingual assessment, but not the intersection of translanguaging and assessment. To check if each article met the inclusion criteria, Jessica skimmed through the entire article, rather than just the abstract, to ensure that we did not eliminate articles that actually aligned, and that we did not include articles that only briefly mentioned translanguaging in assessment, but were empirically focused on a different topic.

Table 2 shows the number of articles that remained for each search term per database after applying the inclusion criteria.

Jessica compiled a list of the remaining titles and abstracts in a shared Google spreadsheet. Then, Zhongfeng and Jamie read through the titles and abstracts and identified articles that should also be disqualified based on the selection criteria and study quality. 37 articles met all selection criteria as agreed upon by all authors and were selected for coding. Four of these articles were later removed as more detailed coding demonstrated that they also failed to meet the inclusion criteria. More specifically, although these articles mentioned translanguaging and/or a heteroglossic perspective, they did not provide relevant data with respect to defining translanguaging, or implementing it as a theoretical framework or in assessment design. Ultimately, we analyzed 33 articles (see the PRISMA flow diagram).

We jointly established a preliminary codebook informed by both emerging patterns and the conceptual framework of translanguaging and assessment. For our coding process, we employed an inductive–deductive hybrid approach (

Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Chia-Hsin and Jessica identified excerpts from each article that aligned with elements of focus including how translanguaging was defined, number of participants, length of study, country/region, research methods, type of assessment (e.g., high-stakes/low-stakes, classroom-based, content area/language). Thematically, our inductive coding surfaced excerpts on

washback on teaching/teachers and learning/students and deductive coding included the themes of

social justice and

equity regarding contextual constraints. Washback refers to the influence that testing exerts on instructional practices and learning processes, encompassing the ways in which assessments shape teaching approaches, learner behaviors, and curricular decisions within educational systems (

Alderson & Banerjee, 2001;

Alderson & Wall, 1993;

Bachman & Palmer, 1996,

2010;

Hughes, 1989). To assure coding consistency, Chia-Hsin and Jessica first completed coding for approximately 30% of the dataset (ten randomly chosen articles), beyond the 20% recommended by

O’Connor and Joffe (

2020) for initial code setting. Based on these independent codings, they calculated Cohen’s Kappa coefficients by code and by study to assess initial intercoder reliability (IRR), which measures independent agreement prior to discussion. Half of the coefficients by code and half of the coefficients by study met a minimum of 95% intercoder agreement per code (

Campbell et al., 2013) which enhances the rigor of data analysis (

O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). All Kappa values indicated an almost perfect agreement of 0.81 or higher (

McHugh, 2012), with the lowest value by code being 0.85, and the lowest value by study being 0.86. For codes showing misalignment, we engaged in consensus discussions consistent with a socially mediated approach to coding, in which discrepancies are collaboratively examined and resolved through dialog and negotiation to ensure shared interpretation (

Campbell et al., 2013). With this rate of intercoder agreement, we used the codebook to create a coder training. Chia-Hsin and Jessica then divided the remaining articles (

n = 33) and coded the rest of the articles, noting any areas of ambiguity for full team review. The full team reviewed the final coding to ensure fidelity across coding of all articles.

After the coding process was complete, the team compiled descriptive statistics to examine the current landscape of translanguaging assessment research, followed by an examination of the affordances and challenges of translanguaging within assessment with respect to (1) washback and (2) social justice. The findings of this analysis are detailed below. A full table of selected 33 articles and their relevant information can be found in the

Supplementary Material.

5. Discussion

Our systematic review builds upon and extends the expanding body of translanguaging research (e.g.,

Hamman-Ortiz et al., 2025) by focusing specifically on the underexplored domain of assessment. While translanguaging has gained significant traction as a pedagogical approach across multilingual classrooms (e.g.,

García & Kleyn, 2016;

Li & García, 2022), assessment remains one of the most monolingually entrenched areas of education (

Shohamy, 2011). Translanguaging pedagogy has long been positioned as a means to affirm multilingual learners’ identities, promote equitable participation, and disrupt deficit discourses, yet assessment continues to lag behind—often reinforcing the very hierarchies that translanguaging seeks to dismantle. Our review addresses this critical gap by examining not only how translanguaging is taken up in assessments but also how these practices interact with broader ideologies, institutional structures, and justice goals.

5.1. Looking Beneath the Surface: Patterns and Silences

Our review of 33 empirical studies revealed promising developments as well as persistent tensions. The prevalence of qualitative, classroom-based, and small-scale studies reflects the localized, relational nature of translanguaging assessment. Teachers in these studies often exercised considerable autonomy in classroom assessment contexts, enabling them to draw on students’ full linguistic repertoires and build stronger connections between home and school literacies. Yet few studies examine standardized or policy-driven contexts, reflecting structural and epistemological barriers that make translanguaging difficult to operationalize at scale. As

Chalhoub-Deville (

2019) notes, multilingual assessments represent

disruptive innovations that challenge the incremental adjustments typical of traditional testing. Designing tasks that allow test-takers to use their full repertoires—and determining how to score such performances—stretch prevailing notions of validity and reliability. While applied linguistics increasingly embraces heteroglossic understandings of multilingualism, standardized testing systems rely on parameters, scales, and comparability logics that conflict with the fluidity of languaging (

Schissel et al., 2019). These tensions help explain why translanguaging assessment encounters systemic resistance: it disrupts the epistemologies of language and measurement that underlie large-scale testing.

Regionally, North America—particularly the United States—remains overrepresented, despite translanguaging’s origins in Welsh bilingual education and its growing relevance across the Global South. This imbalance reflects not only broader academic publishing hierarchies but also epistemic and infrastructural inequities that influence whose research becomes visible. For instance, the underrepresentation of Global South contexts may stem from structural barriers such as publishing language, journal indexing, and epistemic hierarchies privileging English-medium scholarship (see also

Heugh et al., 2017). Nonetheless, emerging work in multilingual testing and translanguaging pedagogy across Africa—such as that of

Antia (

2024) and others advancing decolonial approaches to evaluation—signals a growing momentum that may soon expand to assessment research.

The relative scarcity of European studies warrants a similarly nuanced interpretation. Rather than indicating an absence of multilingual practice, this gap partly reflects how multilingualism is normalized within European educational systems and conceptualized through plurilingualism in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). While plurilingual competence acknowledges integrated linguistic repertoires, it is often operationalized within policy and proficiency frameworks that differ from heteroglossic theories and translanguaging’s connection to social justice. For example, several European publications—such as

De Backer et al. (

2019),

Saville (

2019), and

Margić and Molino (

2022)—were excluded from our dataset because they focus on test accommodations, policy reforms, or pedagogical practices without empirically theorizing assessment through a translanguaging or heteroglossic lens. These regional trends reveal how epistemic visibility and theoretical framing—rather than the actual presence or absence of multilingual practice—shape the contours of translanguaging assessment scholarship worldwide.

Additionally, although most studies were published in applied linguistics journals, only a few appeared in general education or disciplinary-specific journals. This raises important questions about the audiences this research is—and is not—reaching. If translanguaging assessment is to influence practice and policy broadly, it must move beyond linguistics circles and into education, content-area, and policy-focused spaces where assessment discourse is shaped and operationalized.

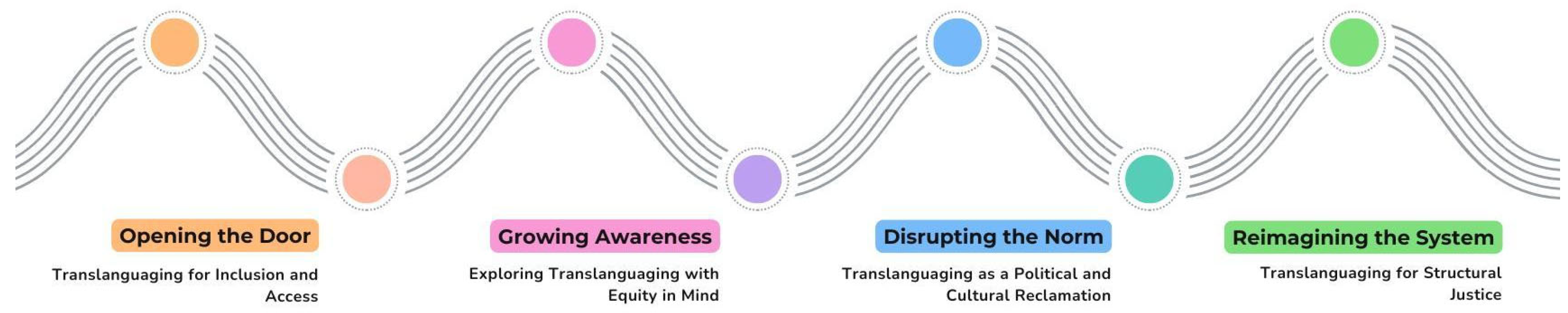

5.2. Interrogating Equity: Insights from the Justice Spectrum

While translanguaging assessment is often celebrated for its equity-promoting potential, our review reveals wide variation in how justice is conceptualized and enacted. This “spectrum of justice” framework illustrates how some studies foreground translanguaging’s instructional benefits, while others use it to disrupt entrenched raciolinguistic hierarchies and reimagine assessment as a decolonial, justice-oriented practice. This conceptual diversity reflects the field’s richness but also points to an urgent need for greater ideological clarity. Without explicit attention to power, race, and language politics, translanguaging risks being reduced to a technical fix rather than a transformative stance. Future work must move beyond descriptive accounts and toward critical inquiry that centers multilingual students’ lived experiences and challenges the systems that marginalize them.

5.3. Implications for Primary, Secondary and Higher Education

In primary and secondary settings, the reviewed studies highlight the affordances of translanguaging assessment in affirming multilingual students’ identities, improving teacher feedback, and fostering authentic demonstrations of learning. Classroom translanguaging assessments can help educators identify and respond to students’ strengths in ways that resist deficit-based placement and tracking practices. Yet many teachers remain constrained by institutional mandates, monolingual testing policies, and a lack of multilingual infrastructure—especially in standardized assessment contexts. This suggests the need for systemic professional development, leadership support, and the development of flexible assessment tools that validate translanguaging as both pedagogically sound and politically necessary.

In higher education, translanguaging assessments can serve as powerful tools to reduce linguistic anxiety, support transnational students, and cultivate more inclusive learning environments. However, resistance remains strong in academic gatekeeping practices—especially in contexts where English proficiency is tied to institutional legitimacy and upward mobility. Faculty may support translanguaging pedagogically but feel constrained by accreditation bodies, monolingual rubrics, or institutional norms. As universities reckon with calls for decolonization and equity, translanguaging assessment offers a concrete practice through which to reimagine linguistic justice in postsecondary education.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Translanguaging in assessment is not merely an accommodation strategy; it is an epistemological and political stance. As our review demonstrates, its implementation can enhance multilingual students’ learning, transform teacher beliefs, and challenge the exclusionary logic of traditional testing. This review emphasized meaningful innovations that have begun to mitigate the persistent inequities that multilingual learners have faced in taking tests in a variety of contexts for decades. Yet for these affordances to be realized broadly, translanguaging must move beyond isolated classroom practices toward systemic reconfiguration of what counts as legitimate knowledge, language, and learning.

Future research should expand geographically to include more studies from the global South and historically marginalized contexts. Methodologically, while the dominance of qualitative studies reflects the relational and exploratory nature of translanguaging, there is a pressing need for more mixed-methods and longitudinal research. Such work can help generate scalable insights that balance the richness of lived experiences with evidence of broader impact. Importantly, however, the call for more quantitative data should not re-center positivist logics that erase linguistic complexity, but rather be rooted in culturally sustaining, justice-oriented frameworks.

To shift the field meaningfully, translanguaging scholarship must also extend its reach. Publishing in applied linguistics journals is crucial—but not sufficient. We urge scholars to engage with general education, teacher education, policy, and content-area outlets to influence a broader range of stakeholders. Simultaneously, we must ensure that multilingual communities themselves—families, students, and educators—are partners in co-creating the assessment tools and policies that affect them.

As assessment continues to shape educational futures, translanguaging offers a timely and necessary intervention. It reminds us that to “sit beside” students in the spirit of assessment’s Latin root, we must honor all of who they are. By reimagining assessment not as a neutral act of measurement, but as a dialogic, relational, and justice-seeking practice, we can begin to build educational systems that reflect the multilingual realities—and aspirations—of the communities we serve.