Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (ADAPT): Properties and Quality of the ADAPT Instrument

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Differentiation

1.2. Assessing Differentiation

1.3. Purpose of the Study

- What support is found for the construct validity of ADAPT?

- 2.

- How reliably do scores on the ADAPT instrument measure the quality of differentiated instruction?

- 3.

- How did raters experience the training and rating process?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The ADAPT Instrument

2.2. Phase 1: Recordings of Lessons and Interviews

2.3. Phase 2: Rater Training & Procedure

2.4. Rater Experience Questionnaire

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. IRT Model

2.5.2. GT Model

3. Results

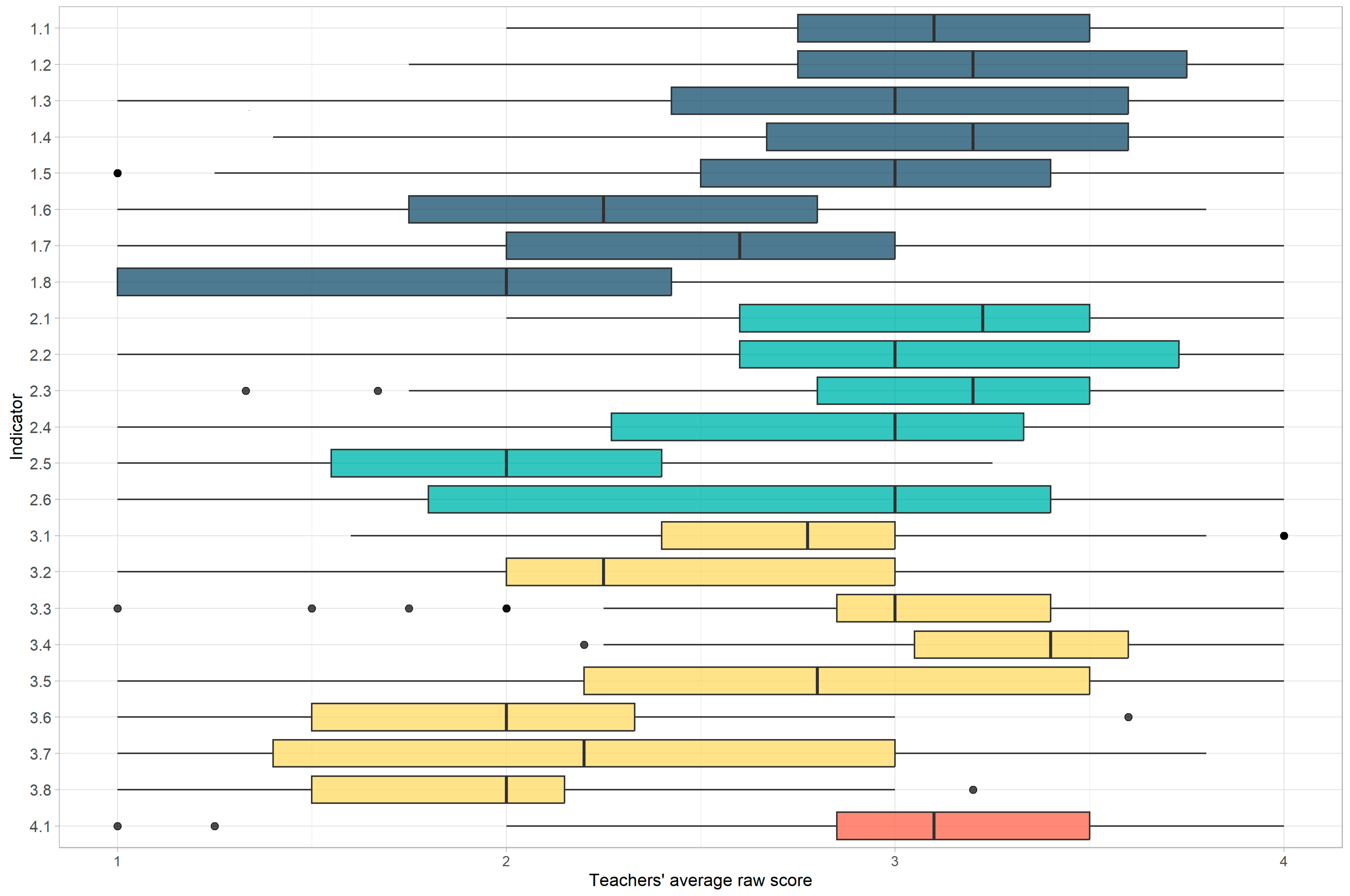

3.1. Descriptives—Raw Scores

3.2. The Structure of ADAPT’s Construct Validity

3.2.1. Descriptives—IRT Model

3.2.2. Agreement and Reliability

3.3. Rater Experiences

With the first teachers, I had less experience in scoring, and during the interviews, I was less able to listen with a specific focus. After scoring several teachers, I became better at filtering what information is relevant for scoring during a lesson or interview, and I could listen more focused.

4. Discussion

4.1. Lessons Learned and Further Research into ADAPT

4.2. Unlocking Possibilities: Educational Research with ADAPT

4.3. Practical Applications: Using ADAPT for Enhancing Differentiation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTA | Cognitive Task Analysis |

| DI | Differentiated Instruction |

| ADAPT | Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (the developed instrument) |

Appendix A

- Response of rater teacher item

- Latent IRT variable related to dimension

- if item loads on dimension otherwise

- Loading of item on dimension , if

- Location of category of item on the latent scale

- Proficiency teacher on dimension with

- Effect of rater on dimension , with

- Error term,

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Abs. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Obs. | Exp. | Obs. | Exp. | Obs. | Exp. | Obs. | Exp. | Dif. |

| 1.1 | 1.59 | 1.62 | 2.03 | 1.99 | 2.29 | 2.26 | 2.45 | 2.49 | 0.03 |

| 1.2 | 1.74 | 1.77 | 2.06 | 2.12 | 2.37 | 2.37 | 2.67 | 2.58 | 0.04 |

| 1.3 | 1.36 | 1.30 | 1.78 | 1.85 | 2.21 | 2.23 | 2.60 | 2.55 | 0.05 |

| 1.4 | 1.45 | 1.50 | 1.98 | 1.97 | 2.42 | 2.31 | 2.53 | 2.60 | 0.06 |

| 1.5 | 1.44 | 1.42 | 1.74 | 1.85 | 2.22 | 2.10 | 2.29 | 2.31 | 0.07 |

| 1.6 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.48 | 1.47 | 1.73 | 1.79 | 0.04 |

| 1.7 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.68 | 1.70 | 2.16 | 2.13 | 0.04 |

| 1.8 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.04 |

| 2.1 | 1.55 | 1.66 | 2.15 | 2.03 | 2.31 | 2.28 | 2.51 | 2.54 | 0.07 |

| 2.2 | 1.24 | 1.21 | 2.00 | 1.83 | 2.17 | 2.24 | 2.49 | 2.58 | 0.09 |

| 2.3 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 2.07 | 2.05 | 2.41 | 2.36 | 2.53 | 2.58 | 0.04 |

| 2.4 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 1.64 | 1.63 | 2.06 | 2.09 | 2.42 | 2.42 | 0.02 |

| 2.5 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 1.29 | 1.15 | 1.51 | 1.60 | 0.07 |

| 2.6 | 1.41 | 1.21 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.75 | 2.11 | 1.99 | 0.15 |

| 3.1 | 1.61 | 1.61 | 1.73 | 1.71 | 1.76 | 1.78 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 0.01 |

| 3.2 | 1.29 | 1.23 | 1.38 | 1.42 | 1.61 | 1.56 | 1.68 | 1.74 | 0.05 |

| 3.3 | 1.92 | 2.00 | 2.03 | 2.07 | 2.18 | 2.12 | 2.22 | 2.18 | 0.06 |

| 3.4 | 2.19 | 2.18 | 2.31 | 2.31 | 2.42 | 2.40 | 2.45 | 2.49 | 0.02 |

| 3.5 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.57 | 1.71 | 2.02 | 2.08 | 2.47 | 2.41 | 0.09 |

| 3.6 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.38 | 1.39 | 0.02 |

| 3.7 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.31 | 1.79 | 1.58 | 0.10 |

| 3.8 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| 4.1 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.43 | 2.27 | 2.34 | 2.42 | 0.08 |

| Item Information Value at: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | −2.000 | −1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 2.000 |

| 1.1 | 0.511 | 0.475 | 0.407 | 0.321 | 0.196 |

| 1.2 | 0.282 | 0.348 | 0.320 | 0.213 | 0.115 |

| 1.3 | 0.302 | 0.467 | 0.509 | 0.294 | 0.118 |

| 1.4 | 0.439 | 0.583 | 0.533 | 0.291 | 0.123 |

| 1.5 | 0.385 | 0.363 | 0.242 | 0.168 | 0.129 |

| 1.6 | 0.223 | 0.330 | 0.402 | 0.402 | 0.326 |

| 1.7 | 0.285 | 0.478 | 0.607 | 0.506 | 0.286 |

| 1.8 | 0.024 | 0.030 | 0.037 | 0.043 | 0.049 |

| 2.1 | 0.181 | 0.287 | 0.303 | 0.203 | 0.103 |

| 2.2 | 0.406 | 0.699 | 0.597 | 0.272 | 0.104 |

| 2.3 | 0.510 | 0.556 | 0.403 | 0.235 | 0.122 |

| 2.4 | 0.343 | 0.867 | 0.705 | 0.335 | 0.178 |

| 2.5 | 0.226 | 0.466 | 0.655 | 0.676 | 0.589 |

| 2.6 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 0.096 | 0.084 | 0.066 |

| 3.1 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.023 |

| 3.2 | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.043 |

| 3.3 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.011 |

| 3.4 | 0.048 | 0.043 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.026 |

| 3.5 | 0.292 | 0.466 | 0.407 | 0.228 | 0.116 |

| 3.6 | 0.148 | 0.207 | 0.270 | 0.353 | 0.398 |

| 3.7 | 0.076 | 0.102 | 0.123 | 0.127 | 0.112 |

| 3.8 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.020 |

| 4.1 | 0.220 | 0.188 | 0.148 | 0.113 | 0.084 |

References

- Ardenlid, F., Lundqvist, J., & Sund, L. (2025). A scoping review and thematic analysis of differentiated instruction practices: How teachers foster inclusive classrooms for all students, including gifted students. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 8, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C. A., Dobbelaer, M. J., Klette, K., & Visscher, A. (2019). Qualities of classroom observation systems. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(6), 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blikstad-Balas, M., Tengberg, M., & Klette, K. (2021). Why—And how—Should we measure instructional quality? In M. Blikstad-Balas, K. Klette, & M. Tengberg (Eds.), Ways of analyzing teaching quality: Potential and pitfalls (pp. 9–20). Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, R., Gibbons, R., & Muraki, E. (1988). Full-information factor analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R. L. (2001). Generalizability theory. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J., Wen, Q., Bi, M., & Lombaerts, K. (2024). How Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is related to Differentiated Instruction (DI): The mediation role of growth mindset and teachers’ practices factors. Social Psychology of Education, 27(6), 3513–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corno, L. (2008). On teaching adaptively. Educational Psychologist, 43(3), 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daltoé, T. L. M. (2024). The assessment of teaching quality through classroom observation—New approaches for teacher education and research. Tübingen. [Google Scholar]

- Deunk, M., Doolaard, S., Smale-Jacobse, A., & Bosker, R. J. (2015). Differentiation within and across classrooms: A systematic review of studies into the cognitive effects of differentiation practices. GION Onderwijs/Onderzoek. [Google Scholar]

- Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A. E., de Boer, H., Doolaard, S., & Bosker, R. J. (2018). Effective differentiation practices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Educational Research Review, 24, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A., Lucassen, W., Meijer, R. R., & Sijtsma, K. (2009). COTAN Beoordelingssysteem voor de kwaliteit van tests [Assessment system for the quality of tests]. Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen/Commissie Testaangelegenheden Nederland. [Google Scholar]

- Eysink, T. H. S., & Schildkamp, K. (2021). A conceptual framework for assessment-informed differentiation (AID) in the classroom. Educational Research, 63(3), 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, C. A., Jorgensen, T. D., & Hove, D. T. (2024). Reducing attenuation bias in regression analyses involving rating scale data via psychometric modeling. Psychometrika, 89, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L. J., De Bruin, K., Lassig, C., & Spandagou, I. (2021). A scoping review of 20 years of research on differentiation: Investigating conceptualisation, characteristics, and methods used. Review of Education, 9(1), 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., Vantieghem, W., & Gheyssens, E. (2020). Exploring the interrelationship between universal design for learning (UDL) and differentiated instruction (DI): A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 29, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuning, T., & van Geel, M. (2021). Differentiated teaching with adaptive learning systems and teacher dashboards: The teacher still matters most. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 14(2), 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuning, T., van Geel, M., & Dobbelaer, M. (2022). ADAPT: Krijg zicht op differentiatievaardigheden. PICA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klette, K. (2023). Classroom observation as a means of understanding teaching quality: Towards a shared language of teaching? Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55(1), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelaan, B. N., Gaikhorst, L., Smets, W., & Oostdam, R. J. (2024). Differentiating instruction: Understanding the key elements for successful teacher preparation and development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 140, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letzel-Alt, V., & Pozas, M. (Eds.). (2023). Differentiated instruction around the world. A global inclusive insight. Waxmann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, F. M. (1980). Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Luoto, J. M., & Selling, A. J. V. (2021). Exploring the potential in using teachers’ intended lesson goals as a context-sensitive lens to understanding observational scores of instructional quality. In M. Blikstad-Balas, K. Klette, & M. Tengberg (Eds.), Ways of analyzing teaching quality: Potential and pitfalls (pp. 229–253). Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T. R. (2005). The role of assessment in differentiation. Theory into Practice, 44(3), 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S. A., Vaughn, M., Scales, R. Q., Gallagher, M. A., Parsons, A. W., Davis, S. G., Pierczynski, M., & Allen, M. (2018). Teachers’ instructional adaptations: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 205–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prast, E. J., van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Kroesbergen, E. H., & van Luit, J. E. H. (2015). Readiness-based differentiation in primary school mathematics: Expert recommendations and teacher self-assessment. Frontline Learning Research, 3(2), 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Guay, F., & Valois, P. (2013). Teaching to address diverse learning needs: Development and validation of a Differentiated Instruction Scale. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(11), 1186–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R. J., Webb, N. M., & Rowley, G. L. (1989). Generalizability theory. American Psychologist, 44(6), 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale-Jacobse, A. E., Meijer, A., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Maulana, R. (2019). Differentiated instruction in secondary education: A systematic review of research evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest, and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2–3), 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher, A. J. (2019). Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Meutstege, K., de Vries, J., Visscher, A., Wolterinck, C., Schildkamp, K., & Poortman, C. (2023). Adapting teaching to students’ needs: What does it require from teachers? In R. Maulana, M. Helms-Lorenz, & R. M. Klassen (Eds.), Effective teaching around the world (pp. 723–736). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M., Göllner, R., & Kleickmann, T. (2025). Reconsidering the measurement of teaching quality using a lens model: Measurement dilemmas and trade-offs. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 36(2), 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principle(s) of Differentiation # | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Indicator | GO | MO | CH | AD | SR | |

| 1. Lesson series preparation | 1.1 | Evaluation of students’ learning achievements | X | X | |||

| 1.2 | Insight into educational needs | X | |||||

| 1.3 | Insight into the range of instruction offered | X | |||||

| 1.4 | Prediction of support needs | X | X | ||||

| 1.5 * | Determination of supplementary remedial objectives and approaches | X | X | ||||

| 1.6 * | Formulation of supplementary enrichment objectives and compilation of a suitable range of instruction | X | X | X | |||

| 1.7 | Organisation of instructional sessions for groups of students | X | |||||

| 1.8 | Involvement of students in the objectives and approach | X | |||||

| 2. Lesson preparation | 2.1 | Determination of lesson objectives | X | ||||

| 2.2 | Composition of instructional groups | X | X | ||||

| 2.3 | Preparation of instruction and processing for the core group | X | |||||

| 2.4 * | Preparation of instruction and processing for the intensive instructional group | X | X | ||||

| 2.5 * | Preparation of instruction and processing for the enrichment group | X | X | X | |||

| 2.6 | Preparation of encouragement for self-regulation | X | |||||

| 3. Actual teaching | 3.1 | Sharing of the lesson objective | X | ||||

| 3.2 | Activation and inventory of prior knowledge | X | |||||

| 3.3 * | Providing didactically sound and purposive core instruction | X | |||||

| 3.4 | Monitoring of comprehension and the working process | X | |||||

| 3.5 * | Instruction and processing for the intensive group in the lesson | X | X | X | |||

| 3.6 * | Challenging the enrichment group in the lesson | X | X | ||||

| 3.7 | Encouragement of self-regulation during the lesson | X | |||||

| 3.8 | Conclusion of the lesson | X | X | ||||

| 4. Evaluation | 4.1 | Evaluation and determination of follow-up actions | X | X | X | ||

| n | |

|---|---|

| Grade taught | |

| 1 | 9 |

| 2 | 11 |

| 3 | 17 |

| 4 | 24 |

| 5 | 24 |

| 6 | 26 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 26 (30.2%) |

| Female | 60 (69.8%) |

| Indicator | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | nei | n/a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Evaluation of students’ learning achievements | 9 | 68 | 192 | 120 | 10 | - |

| 1.2 | Insight into educational needs | 3 | 74 | 138 | 161 | 23 | - |

| 1.3 | Insight into the range of instruction offered | 23 | 115 | 71 | 163 | 27 | - |

| 1.4 | Prediction of support needs | 16 | 89 | 116 | 166 | 12 | - |

| 1.5 * | Determination of supplementary remedial objectives and approaches | 38 | 35 | 197 | 85 | 39 | 5 |

| 1.6 * | Formulation of supplementary enrichment objectives and compilation of a suitable range of instruction | 76 | 148 | 113 | 35 | 17 | 10 |

| 1.7 | Organisation of instructional sessions for groups of students | 70 | 129 | 117 | 77 | 6 | - |

| 1.8 | Involvement of students in the objectives and approach | 132 | 114 | 29 | 35 | 89 | - |

| 2.1 | Determination of lesson objectives | 1 | 115 | 90 | 173 | 20 | - |

| 2.2 | Composition of instructional groups | 45 | 76 | 89 | 175 | 14 | - |

| 2.3 | Preparation of instruction and processing for the core group | 24 | 59 | 141 | 156 | 19 | - |

| 2.4 * | Preparation of instruction and processing for the intensive instructional group | 73 | 25 | 139 | 102 | 46 | 14 |

| 2.5 * | Preparation of instruction and processing for the enrichment group | 103 | 147 | 85 | 14 | 36 | 14 |

| 2.6 | Preparation of encouragement for self-regulation | 90 | 68 | 73 | 123 | 45 | - |

| 3.1 | Sharing of the lesson objective | 14 | 135 | 183 | 64 | 3 | - |

| 3.2 | Activation and inventory of prior knowledge | 87 | 138 | 56 | 114 | 4 | - |

| 3.3 * | Providing didactically sound and purposive core instruction | 12 | 34 | 248 | 96 | 0 | 9 |

| 3.4 | Monitoring of comprehension and the working process | 5 | 48 | 149 | 196 | 1 | - |

| 3.5 * | Instruction and processing for the intensive group in the lesson | 68 | 43 | 110 | 125 | 16 | 37 |

| 3.6 * | Challenging the enrichment group in the lesson | 101 | 179 | 56 | 18 | 26 | 19 |

| 3.7 | Encouragement of self-regulation during the lesson | 136 | 99 | 102 | 57 | 5 | - |

| 3.8 | Conclusion of the lesson | 106 | 234 | 30 | 16 | 13 | - |

| 4.1 | Evaluation and determination of follow-up actions | 15 | 48 | 174 | 130 | 32 | - |

| Covariance Matrix (Teachers) | Correlation Matrix (Teachers) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO | MO | CH | AD | SR | GO | MO | CH | AD | SR | ||

| GO | 0.190 | 0.143 | 0.027 | 0.079 | 0.081 | GO | 1.000 | 0.572 | 0.067 | 0.457 | 0.194 |

| MO | 0.143 | 0.330 | 0.141 | 0.114 | 0.116 | MO | 0.572 | 1.000 | 0.264 | 0.503 | 0.210 |

| CH | 0.027 | 0.141 | 0.864 | 0.068 | 0.292 | CH | 0.067 | 0.264 | 1.000 | 0.184 | 0.327 |

| AD | 0.079 | 0.114 | 0.068 | 0.157 | 0.133 | AD | 0.457 | 0.503 | 0.184 | 1.000 | 0.351 |

| SR | 0.081 | 0.116 | 0.292 | 0.133 | 0.921 | SR | 0.194 | 0.210 | 0.327 | 0.351 | 1.000 |

| Principle of Differentiation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | GO | MO | CH | AD | SR |

| 1.1 | 0.572 | 1.421 | |||

| 1.2 | 1.665 | ||||

| 1.3 | 1.890 | ||||

| 1.4 | 0.911 | 1.211 | |||

| 1.5 | 0.531 | 0.950 | |||

| 1.6 | 0.259 | 0.909 | 0.918 | ||

| 1.7 | 2.295 | ||||

| 1.8 | 0.468 | ||||

| 2.1 | 1.839 | ||||

| 2.2 | 0.171 | 1.868 | |||

| 2.3 | 1.721 | ||||

| 2.4 | 0.989 | 1.425 | |||

| 2.5 | 0.297 | 0.838 | 1.629 | ||

| 2.6 | 0.933 | ||||

| 3.1 | 0.637 | ||||

| 3.2 | 0.313 | ||||

| 3.3 | 0.657 | ||||

| 3.4 | 0.340 | ||||

| 3.5 | 0.710 | 0.031 | 1.092 | ||

| 3.6 | 0.691 | 1.081 | |||

| 3.7 | 0.937 | ||||

| 3.8 | 0.412 | 0.400 | |||

| 4.1 | 0.655 | 0.252 | 0.363 | ||

| Agreement | ||||||

| Raters | ALL | GO | MO | CH | AD | SR |

| 2 | 0.635 | 0.659 | 0.752 | 0.858 | 0.616 | 0.692 |

| 3 | 0.719 | 0.743 | 0.820 | 0.900 | 0.706 | 0.771 |

| 4 | 0.771 | 0.794 | 0.858 | 0.923 | 0.762 | 0.818 |

| 5 | 0.807 | 0.828 | 0.883 | 0.938 | 0.800 | 0.849 |

| Reliability | ||||||

| Raters | ALL | GO | MO | CH | AD | SR |

| 1 | 0.860 | 0.738 | 0.831 | 0.928 | 0.700 | 0.932 |

| 2 | 0.923 | 0.849 | 0.908 | 0.963 | 0.823 | 0.965 |

| 3 | 0.947 | 0.894 | 0.936 | 0.975 | 0.875 | 0.976 |

| 4 | 0.959 | 0.919 | 0.952 | 0.981 | 0.903 | 0.982 |

| 5 | 0.967 | 0.934 | 0.961 | 0.985 | 0.921 | 0.986 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Geel, M.; Keuning, T.; Dobbelaer, M.; Glas, C. Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (ADAPT): Properties and Quality of the ADAPT Instrument. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111530

van Geel M, Keuning T, Dobbelaer M, Glas C. Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (ADAPT): Properties and Quality of the ADAPT Instrument. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111530

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Geel, Marieke, Trynke Keuning, Marjoleine Dobbelaer, and Cees Glas. 2025. "Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (ADAPT): Properties and Quality of the ADAPT Instrument" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111530

APA Stylevan Geel, M., Keuning, T., Dobbelaer, M., & Glas, C. (2025). Assessing Differentiation in All Phases of Teaching (ADAPT): Properties and Quality of the ADAPT Instrument. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111530