Mapping the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory in Education: A Scoping Review on Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions and Theoretical Frameworks

1.2. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

1.3. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

1.4. Toward an Integrated Framework

1.5. Aim of This Study and Research Objectives

- RQ1.

- In what ways have TPB and SDT been integrated in educational research to explain teachers’ behavioral intentions?

- RQ2.

- What methodological approaches and analytical strategies are most employed in studies that combine TPB and SDT?

2. Materials and Methods

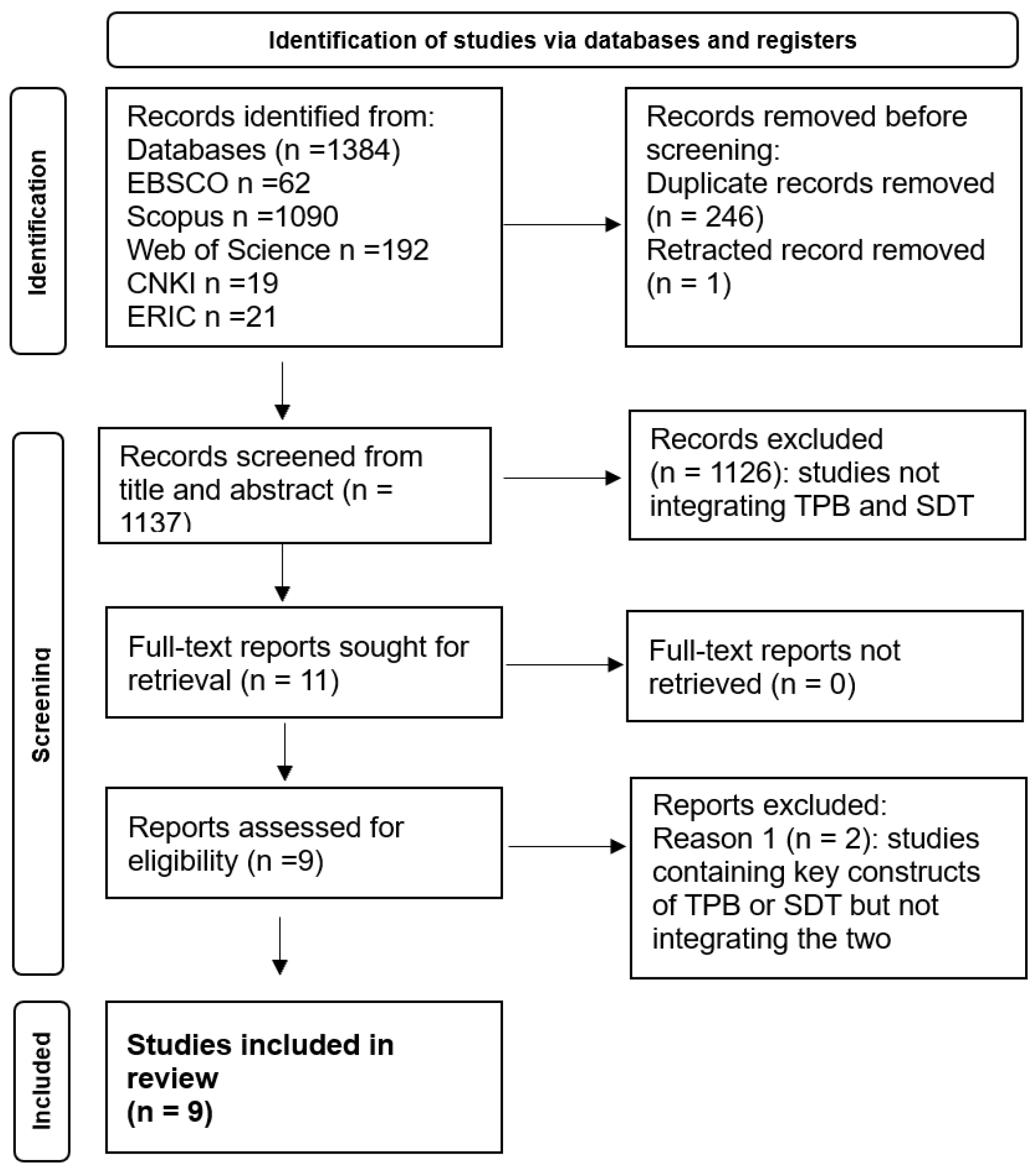

2.1. Protocol and Screening Process

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.3.1. Database Selection

- Scopus and WoS: For their robust bibliometric data and coverage of high-impact interdisciplinary journals.

- EBSCO (specifically, the “Academic Search Complete” and “Education Research Complete” subcollections): To access an extensive repository of education-focused studies, including those not indexed in larger multidisciplinary databases.

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center): For its exclusive focus on educational research, ensuring a strong emphasis on studies related to teachers’ behavioral intentions.

- CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure 中国知网): To incorporate Chinese-language literature, expanding the cultural and linguistic diversity of the review. Searches were conducted via the international version of CNKI (https://oversea.cnki.net/ (accessed on 26 September 2025)). Full texts were accessed through institutional partnerships or by direct contacting authors when access was restricted.

2.3.2. Search Strategy and Filtering Techniques

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. TPB and SDT Integration in Educational Research in Response to RQ1

3.2.1. Theoretical Integration Approaches

3.2.2. Constructs from SDT and TPB

3.3. Methodological Approaches and Analytical Strategies in Response to RQ2

3.3.1. Methodological and Contextual Characteristics

3.3.2. Summary of Predictive Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Methodological Implications

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I. (2019). College students’ entrepreneurial intention: Testing an integrated model of SDT and TPB. Sage Open, 9(2), 2158244019853467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H., & Gündüzalp, C. (2024). A unified framework for understanding teachers’ adoption of robotics in STEM education. Education and Information Technologies, 29(11), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H., & Yilmaz, R. M. (2024). A comprehensive model explaining teachers’ intentions to use mobile-based assessment. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(8), 4063–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J. M., Iwanaga, K., Chiu, C. Y., Cotton, B. P., Deiches, J., Morrison, B., Moser, E., & Chan, F. (2017). Relationships between self-determination theory and theory of planned behavior applied to physical activity and exercise behavior in chronic pain. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(7), 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D., Canova, L., Capasso, M., & Bianchi, M. (2024). Integrating the theory of planned behavior and the self-determination theory to promote Mediterranean diet adherence: A randomized controlled trial. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasteen, S. V., & Chattergoon, R. (2020). Insights from the Physics and Astronomy new faculty workshop: How do new Physics faculty teach? Physical Review Physics Education Research, 16(2), 020164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Marsh, H. W., & Song, Y.-G. (2022). Intervention-enabled autonomy-supportive teaching improves the PE classroom climate to reduce antisocial behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 60, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P. K., Zhang, C. Q., Liu, J. D., Chan, D. K. C., Si, G., & Hagger, M. S. (2017). The process by which perceived autonomy support predicts motivation, intention, and behavior for seasonal influenza prevention in Hong Kong older adults. BMC Public Health, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., Wang, J., Zhou, Q., & Lin, Y. (2022, July 19–22). Understanding K12 teachers’ continuance intention and behavior toward online learning communities [Conference session]. IEEE 2022 International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET) (pp. 93–97), Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, T. A., & Greene, B. A. (2011). Preservice teachers’ beliefs, attitudes, and motivation about technology integration. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 45(1), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierendonck, C., Poncelet, D., & Tinnes-Vigne, M. (2024). Why teachers do (or do not) implement recommended teaching practices? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1269954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, S., & Köseoğlu, P. (2022). A Review of studies in the field of Educational Sciences within the context of Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 19, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A., & Singh, C. (2025). Using unguided peer collaboration to facilitate early educators’ pedagogical development: An example from Physics TA training. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorozidis, G., & Papaioannou, A. G. (2014). Teachers’ motivation to participate in training and to implement innovations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M., Haas, M. R. C., Daniel, M., & Chan, T. M. (2021). The scoping review: A flexible, inclusive, and iterative approach to knowledge synthesis. AEM Education and Training, 5(3), e10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2009). Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Health Psychology, 14(2), 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Harris, J. (2006). From psychological need satisfaction to intentional behavior: Testing a motivational sequence in two behavioral contexts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J., & Yin, H. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1217819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Yin, H., & Wang, W. (2016). The effect of tertiary teachers’ goal orientations for teaching on their commitment: The mediating role of teacher engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X. Y., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from Self-Determination Theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 16(6), 1300–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, G., Barry, D. M., Alford, K., Jagger, C. B., & Roberts, T. G. (2024). Why pursue a career in teaching agriculture? Application of self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Agricultural Education, 65(2), 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifarajimi, M., Bolaji, S., Mason, J., & Jalloh, S. (2025). Teachers’ beeliefs about mentoring practices in Nigeria’s public school system: A proposed framework to curb teacher attrition. Education Sciences, 15(5), 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J., & Blanton, H. (2005). The origins and structure of attitudes. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 125–172). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, E., de Boer, A., Bakker, A., de Jong, F., & Minnaert, A. (2024). Explaining teachers’ behavioural intentions towards differentiated instruction for inclusion: Using the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Self-Determination Theory. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(4), 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A., Cao, X., Ali, A., Masood, A., & Yu, L. (2017). Empirical investigation of Facebook discontinues usage intentions based on SOR paradigm. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 544555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for conducting a scoping review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(5), 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Espina, S., Prieto-Saborit, J. A., Méndez-Alonso, D., Jiménez-Arberas, E., Llosa, J. A., & Nistal-Hernández, P. (2025). The relationship between the motivational style of teachers and the implementation of cooperative learning: A self-determination theory approach. Sustainability, 17(8), 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. (2001). A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocete, C., González-Peño, A., Gutiérrez-Suárez, A., & Franco, E. (2025). The effects of a self-determination theory based training program on teaching styles adapted to inclusive Physical Education. Does previous contact with students with intellectual disabilities matter? Espiral Cuadernos del Profesorado, 18(37), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M. P., Cuskelly, M., Pedersen, S. J., & Rayner, C. S. (2021). Applying the theory of planned behaviour in assessments of teachers’ intentions towards practicing inclusive education: A scoping review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(4), 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. (2024). Modeling college EFL teachers’ intentions to conduct academic research: Integrating theory of planned behavior with self-determination theory. PLoS ONE, 19(8), e0307704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slemp, G. R., Field, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Forner, V. W., Van den Broeck, A., & Lewis, K. J. (2024). Interpersonal supports for basic psychological needs and their relations with motivation, well-being, and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 127(5), 1012–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniehotta, F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2013). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 7(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, H., Knappstein, M., Ajzen, I., Schmidt, P., & Kabst, R. (2016). How effective are behavior change interventions based on the theory of planned behavior? A three-level meta-analysis. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 224(3), 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Mesa, A. M., & Gómez, R. L. (2024). Does teachers’ motivation have an impact on students’ scientific literacy and motivation? An empirical study in Colombia with data from PISA 2015. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestal, S. S., Burke, R. S., Browning, L. M., Hasselquist, L., Hales, P. D., Miller, M. L., Nepal, M. P., & White, P. T. (2025). Building resilience in rural STEM teachers through a Noyce Professional Learning Community. Education Sciences, 15(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, S., Wind, S. A., & Gill, C. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of Self-Determination-Theory-based interventions in the education context. Learning and Motivation, 87, 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. L., Bennie, A., Vasconcellos, D., Cinelli, R., Hilland, T., Owen, K. B., & Lonsdale, C. (2021). Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T. T., Cao, Y., & Habibi, A. (2024). Critical factors affecting the participation of mathematics teachers in professional development training. Current Psychology, 43(43), 33180–33195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. M., & Rodgers, W. M. (2004). The relationship between perceived autonomy support, exercise regulations and behavioural intentions in women. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Gazi, M. A. I., Faisal-E-Alam, M., & Emon, M. (2025). Chinese students’ English language learning intention and behavior: Mediating effect of attitude and moderating effect of institutional support. Acta Psychologica, 260, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Field | Boolean Combination | Temporal Filter |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBSCO | Title, Abstract, Keywords | (“Theory of Planned Behavior” OR “TPB”) AND (“Self-Determination Theory” OR “SDT”) | 2010–2024 (due to export restriction) |

| ERIC | Title, Abstract, Keywords | (“Theory of Planned Behavior” OR “TPB”) AND (“Self-Determination Theory” OR “SDT”) | No filter applied |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY fields | (“Theory of Planned Behavior” OR “TPB”) AND (“Self-Determination Theory” OR “SDT”) | No filter applied |

| WoS | Topic (Title, Abstract, Keywords) | (“Theory of Planned Behavior” OR “TPB”) AND (“Self-Determination Theory” OR “SDT”) | No filter applied |

| CNKI | Title, Abstract, Keywords (in Chinese) * | (“计划行为理论”) AND (“自我决定理论”) | No filter applied |

| ID | Authors (Year) | Title | Journal | Country | Sample | Research Type | Constructs Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ateş and Gündüzalp (2024). | A unified framework for understanding teachers’ adoption of robotics in STEM education | Education and Information Technologies | Turkey | In-service teachers | quantitative | Autonomy, competence, relatedness, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and intention |

| 2 | Ateş and Yilmaz (2024) | A comprehensive model explaining teachers’ intentions to use mobile-based assessment | Interactive Learning Environments | Turkey | In-service teachers and pre-service teachers | quantitative | Autonomy, competence, relatedness, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and intention |

| 3 | Chasteen and Chattergoon (2020) | Insights from the Physics and Astronomy New Faculty Workshop: How Do New Physics Faculty Teach? | Physical Review Physics Education Research | USA | In-service teachers | quantitative | Relatedness, competence, autonomy, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control |

| 4 | Cui et al. (2022). | Understanding K12 Teachers’ Continuance Intention and Behavior toward Online Learning Communities | Conference paper | China | In-service teachers | quantitative | Autonomy, competence, relatedness, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, intention-continuance, intention, and behavior |

| 5 | Cullen and Greene (2011) | Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs, Attitudes, and Motivation about Technology Integration. | Journal of Educational Computing Research | USA | Pre-service teachers | qualitative | Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amotivation, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and intention |

| 6 | Hur et al. (2024) | Why Pursue a Career in Teaching Agriculture? Application of Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior | Journal of Agricultural Education | USA | Pre-service teachers | Mixed approach | Intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, amotivation, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, intention, and behavior |

| 7 | Kupers et al. (2024). | Explaining teachers’ behavioral intentions towards differentiated instruction for inclusion: Using the theory of planned behavior and the self-determination theory. | European Journal of Special Needs Education | The Netherlands | In-service teachers | quantitative | Perceived autonomy, perceived competence, perceived relatedness, attitudes, perceived behavior control, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions |

| 8 | Ren (2024). | Modeling college EFL teachers’ intentions to conduct academic research: Integrating theory of planned behavior with self-determination theory. | PLoS ONE | China | In-service teachers | quantitative | Autonomous motivation, Controlled motivation, Attitudes, Subjective norms, Perceived Behavior Control |

| 9 | Wijaya et al. (2024) | Critical factors affecting the participation of mathematics teachers in professional development training | Current Psychology | China | In-service teachers | quantitative | Relatedness, participating interest, training value, facilitating conditions, quality of training, attitude, subjective norms, training optimism (treated as a TPB-related belief/expectancy variable in this model), and participation intention (as the TPB dependent variable) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Q.; Martínez-Hernández, C.; Peña-Martínez, J. Mapping the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory in Education: A Scoping Review on Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111529

Jia Q, Martínez-Hernández C, Peña-Martínez J. Mapping the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory in Education: A Scoping Review on Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111529

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Qian, Carlos Martínez-Hernández, and Juan Peña-Martínez. 2025. "Mapping the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory in Education: A Scoping Review on Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111529

APA StyleJia, Q., Martínez-Hernández, C., & Peña-Martínez, J. (2025). Mapping the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory in Education: A Scoping Review on Teachers’ Behavioral Intentions. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111529