Participation in Tasks Outside the Classroom and the Educational Institution of Non-University Teachers in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The scope of the School and the Teaching Staff, whose main function is to deliver the teaching prescribed by existing regulations.

- The Technical–Political scope, whose function is to regulate and supervise the education system.

- The Teacher Training scope, with the function of preparing individuals for the teaching role.

- The Scientific–Academic scope, with the function of producing knowledge for the teaching profession and the educational field in general; sometimes articulated with the previous scope.

- The existence of prolonged, systematic initial training with a significant common theoretical base for all future professionals in the field, prior to any specialization.

- Initial training characterized by high academic and professional demands, equally reflected in the requirements for obtaining the degree or certification.

- (a)

- Participation in debates, policies, and other matters that define the field and the profession.

- (b)

- Direct participation in the production of insights related to their field.

- (c)

- Involvement in initial and continuous training practices for future professionals in the field.

1.1. Specific Background on Teacher Participation in the Three Scopes of Action

1.2. Common Tasks That Define Each Scope

- (1)

- Participation of teaching staff in tasks/functions within the Technical–Political scope:

- Counseling professionals external to the school.

- Taking part in socio-educational debates with other external professionals.

- Participating in the development of educational regulations/policies.

- Advising and/or collaborating on educational matters with foundations/associations, unions, international organizations, etc.

- Sharing opinions, knowledge, and/or materials on social media.

- (2)

- Participation of teaching staff in tasks/functions within the Scientific–Academic scope:

- Conducting research with other institutions outside the school.

- Presenting papers at conferences.

- Developing textbooks and/or didactic materials for students/teaching staff.

- Writing books or book chapters, articles in journals or newspapers.

- (3)

- Participation of teaching staff in tasks/functions within the Teacher Training scope:

- Training future teachers in undergraduate degrees for Early Childhood or Primary Education.

- Training future teachers in the master’s program for Secondary Education.

- Providing continuous training courses for other teachers.

- Developing materials for teacher training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Sample

2.2. Measuring Tool

2.3. Measurement Variables

- (1)

- Scopes of teacher participation outside the classroom-school: Continuous quantitative variables obtained by summing the scores of the items from each dimension of the questionnaire. Three main non-traditional scopes of teacher participation were considered: the Technical–Political scope, the Scientific–Academic scope, and the Teacher Training scope.

- (2)

- Educational Level: An ordinal variable with three levels (Early Childhood, Primary, and Secondary Education). This is defined as the educational level at which the teacher performs their primary or sole professional duties.

- (3)

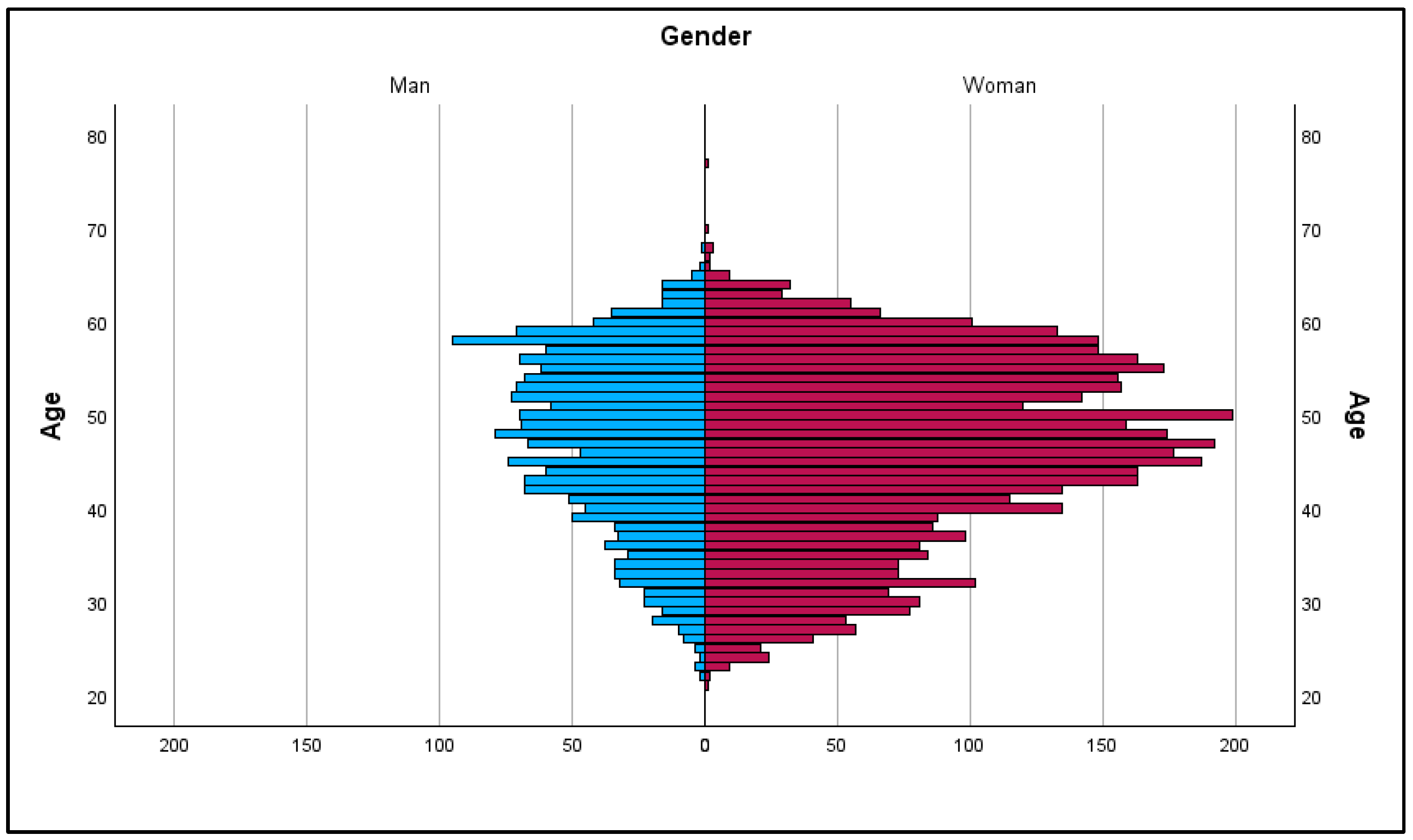

- Gender: A dichotomous nominal variable (Man and Woman). For analytical purposes, despite offering the option to leave this item blank or select choices such as “Other” or “Prefer not to say,” these response options were excluded from the analysis due to their very small sample size.

- (4)

- Age: A discrete quantitative variable within an age range of 18 to 67 years (the current mandatory retirement age in Spain).

- (5)

- Work Experience: An ordinal variable with seven levels, distributed in closed five-year intervals, except for the last, which is an open-ended interval. This is defined as the length of time the teacher has been practicing in their current profession, categorized in five-year ranges.

- (6)

- School Type: A nominal variable with three levels (Public, Government-Subsidized Private, and Private). This defines the type of school based on its funding source: public, private, or mixed.

- (7)

- Management Role: A dichotomous nominal variable (Yes/No) determining whether the teacher currently holds a role in the school’s management team.

- (8)

- Institutional Affiliation of Credential-Granting University: A nominal variable with three levels (Public and Private). This defines the type of the teacher training institution based on its funding source, whether public or private.

- (9)

- Continuing Teacher Training (CTT): An ordinal variable with five levels, distributed in closed three-year intervals, except for the last which is an open-ended interval. This is defined as the number of CTT courses of at least 10 h completed within the last 6 years.

2.4. Data Analysis Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Early Childhood Education

4.2. Primary Education

4.3. Secondary Education

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abror, S., Purnomo, Mutrofin, M., Hardinanto, E., & Mintarsih, M. (2024). Reimagining teacher professional development to link theory and practice. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H. E., & Ruef, M. (2006). Organizations evolving. SAGE Publication Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Amitai, A., & Van Houtte, M. (2022). Being pushed out of the career: Former teachers’ reasons for leaving the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelehin, A. A., Ajuluchukwu, P., Okonkwo, C. A., Imohiosen, C. E., & Iguma, D. R. (2025). Enhancing teacher training for social improvement in education: Innovative approaches and best practices. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 51(2), 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azorín, C., & Hernández, E. (2024). Leading professional networks in education: Developing connected autonomy across the territory? School Leadership & Management, 44(3), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, D., & Altunay, E. (2025). The interplay of school cultural dynamics and change: Exploring the resistance to school change. European Journal of Education, 60(1), e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmark, U. (2023). Teachers’ professional learning when building a research-based education: Context-specific, collaborative and teacher-driven professional development. Professional Development in Education, 49(2), 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (2002). Campo de poder/campo intelectual. Montressor. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (2014). Intelectuales, política y poder. EUDEBA. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C., White, R., & Kelly, A. (2023). Teachers as educational change agents: What do we currently know? Findings from a systematic review. Emerald Open Research, 1(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, F., Batruch, A., Autin, F., Mugny, G., Quiamzade, A., & Pulfrey, C. (2021). Teaching as social influence: Empowering teachers to become agents of social change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 15(1), 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M. P., O’Bryan, A. E., Strayer, J. F., McNicholl, T. H., & Hagman, J. E. (2024). Considering, piloting, scaling and sustaining a research-based precalculus curriculum and professional development innovation. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 73, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. P., & Kamal Kumar, K. (2025). The role of preschool and primary school teachers in curriculum development. Research on Preschool and Primary Education, 3(1), 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbunde, P., & Moreeng, B. B. (2024). The sustainability of curriculum reform and implementation through teacher participation: Evidence from social studies teachers. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 6(1), 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A., Triggs, V., & Nielsen, W. (2014). Cooperating teacher participation in teacher education: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 84(2), 163–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., Craig, C. J., Orland-Barak, L., Cole, C., & Hill-Jackson, V. (2022). Agents, agency, and teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 73(5), 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, S., Thompson, G., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Hogan, A. (2025). Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: A systematic research synthesis. Educational Review, 77(2), 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-González, C., Rodríguez, C. L., & Segovia, J. D. (2021). A systematic review of principals’ leadership identity from 1993 to 2019. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(1), 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, S., & Viana, J. (2023). Teachers as curriculum designers: What knowledge is needed? The Curriculum Journal, 34(3), 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolenc Orbanić, N., & Kovač, N. (2021). Environmental awareness, attitudes, and behaviour of preservice preschool and primary school teachers. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 20(3), 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin-Rousseau, S., Morin, A. J., Fernet, C., Blechman, Y., & Gillet, N. (2024). Teachers’ profiles of work engagement and burnout over the course of a school year. Applied Psychology, 73(1), 57–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, X., Sorensen, T. B., & Paine, L. (2024). World yearbook of education 2025. The teaching profession in a globalizing world: Governance, career, learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- El Oraiby, B. (2025). Teachers’ professional development problems and possible strategies to enhance it. European Journal of Education Studies, 12(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. (2019). Implicit and informal professional development: What it ‘looks like’, how it occurs, and why we need to research it. Professional Development in Education, 45(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Molina-Fernández, E., & Fernández-Batanero, J. M. (2021). Mapping teacher collaboration for school success. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(4), 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D., Blundell, C., Mills, R., & Bourke, T. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and reform: A systematic literature review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(3), 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, L. (2015). Teacher unions’ participation in policy making: A South African case study. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(2), 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Núñez, M. I., Cano-Muñoz, M. A., & Torregrosa, M. S. (2020). Manual para investigar en Educación. Narcea. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham-Caston, M., & DiCarlo, C. F. (2023). Leadership styles in childcare directors. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. S. (2025). Professional learning at scale-navigating complexities and sustaining collaboration. Scottish Educational Review, 55(1–2), 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilferty, F. (2008). Theorizing teacher professionalism as an enacted communication of power. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegstad, K. M., Fiskum, T. A., Aspfors, J., & Eklund, G. (2022). Dichotomous and multifaceted: Teacher educators’ understanding of professional knowledge in research-based teacher education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(6), 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2021). When is high workload bad for teacher wellbeing? Accounting for the non-linear contribution of specific teaching tasks. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. (2021). Does teacher engagement matter? Exploring relationship between teachers’ engagement in professional development and teaching practice. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 3(4), 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, M., & Bezzina, C. (2022). The professional development needs of beginning and experienced teachers in four municipalities in Sweden. Professional Development in Education, 48(4), 624–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesim, E., Atmaca, T., & Turan, S. (2025). Reshaping School Cultures: AI’s Influence on Organizational Dynamics and Leadership Behaviors. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 24(1), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairiah, A. A., Amin, A., Muassomah, M., Mareta, M., Sulistyorini, S., & Yusuf, M. (2024). Challenges to professional teacher development through workplace culture management. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13(2), 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoulas, A., Babić, S., Glettler, C., Karner, A., Mercer, S., & Seidl, E. (2019). Lost in research: Educators’ attitudes towards research and professional development. Teacher Development, 23(3), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M. A., & Novicoff, S. (2024). Time in school: A conceptual framework, synthesis of the causal research, and empirical exploration. American Educational Research Journal, 61(4), 724–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambirth, A., Cabral, A., & McDonald, R. (2019). Transformational professional development: (re)claiming agency and change (in the margins). Teacher Development, 23(3), 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, N., Moltó, M. L., Sánchez, R., & Simó-Noguera, C. (2022). Desigualdad de género en el trabajo doméstico en España. REIS: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, (180), 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S., & Hogan, A. (2019). Reform first and ask questions later? The implications of (fast) schooling policy and ‘silver bullet’ solutions. Critical Studies in Education, 60(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magda, I., Cukrowska-Torzewska, E., & Palczyńska, M. (2024). What if she earns more? Gender norms, income inequality, and the division of housework. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 45(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarranz, M. (2023). Aspectos clave de la profesionalización docente. Una revisión bibliográfica. Cuestiones Pedagógicas, 2(31), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2008). Investigación Educativa. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación, Formación Profesional y Deportes. (2025, de marzo de 30). Enseñanzas no universitarias. Estadísticas del Profesorado y otro personal. Available online: https://bit.ly/42hnM0P (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Monarca, H. (2021). Ciencia, poder y regímenes de verdad en textos académicos sobre acceso a la profesión docente. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 29(81). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monarca, H., Mera, A., Álvarez, G., & Gorostiaga, J. (2024). Posiciones sobre profesionalización docente en el discursode los organismos internacionales [Stances on Teacher Pro-fessionalization in the Discourse of International Organizations]. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 29(102), 509–533. [Google Scholar]

- Monarca, H., Rappoport, S., Pericacho, J., Mottareale, D., Gratacós, G., Azorín, C., Ruiloba, J., & Messina, C. (2025). Perceptions of the teaching profession and its professionalisation in Spain. European Journal of Education, 60(1), e12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoyerro González, P. (2022). La educación concertada en España: Origen y recorrido histórico. Historia de la Educación, 41, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlemann, S., Imhof, M., & Bellhäuser, H. (2023). Implementing reform in the teacher education system: Concerns of teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 126, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostinelli, G., & Crescentini, A. (2024). Policy, culture and practice in teacher professional development in five European countries. A comparative analysis. Professional Development in Education, 50(1), 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozas, M., Letzel-Alt, V., & Schwab, S. (2023). The effects of differentiated instruction on teachers’ stress and job satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romiszowski, A. J. (2024). Producing instructional systems: Lesson planning for individualized and group learning activities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salavera, C., Urbón, E., Usán, P., Franco, V., Paterna, A., & Aguilar, J. M. (2024). Psychological wellbeing in teachers. Study in teachers of early childhood and primary education. Heliyon, 10(7), e28868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña Vadillo, V. (2024). Estereotipos de género en las trayectorias de los profesionales masculinos dedicados a la Educación Infantil. Márgenes, 5(2), 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind, N. J. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafidou, J. O., & Chatziioannidis, G. (2013). Teacher participation in decision making and its impact on school and teachers. International Journal of Educational Management, 27(2), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R. (2023). La (No)Evolución de la formación inicial de los profesores de primaria en España en los últimos 40 años vista a través de TALIS. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, (43), 400–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., & Pericacho-Gómez, F. J. (2021). Profile and perceptions of the students of the Master in secondary education teacher training in Spain. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 15(30), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., Pericacho-Gómez, F. J., Moraleda-Esteban, R., & Monarca, H. (2025). Use of working time in the teaching profession in Spain: The cases of Galicia and the Basque country. Online First. International Journal of Changes in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, K. (2023). The influence of organizational culture, leadership, and motivation on performance of early childhood school teachers. Journal of Childhood Development, 3(1), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, E. (2023). “I don’t want to be helpless”: Learning policymaking with teachers. Arts Education Policy Review, 124(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaller, H. (2015). The teacher disempowerment debate: Historical reflections on “slender autonomy”. Paedagogica Historica, 51(1–2), 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A. C. D., Alexandre, N. M. C., & Guirardello, E. D. B. (2017). Psychometric properties in instruments evaluation of reliability and validity. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 26, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T. T., & Jansky, T. A. (2022). Novice teachers and embracing struggle: Dialogue and reflection in professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education: Leadership and Professional Development, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatto, M. T. (2024). The future of teacher education and teacher professionalism in the face of global policy trends. In World yearbook of education 2025 (pp. 160–176). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M., Ortiz-Mallegas, S., & Grana, I. (2024). Regulación de la formación y la profesionalización docente en Inglaterra implicaciones en la autonomía profesional y la acción sindical. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, 44, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Valle López, J., & Matarranz, M. (2023). Discursos supranacionales y estudios comparados sobre la profesionalización docente. Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Wideen, M. F., Mayer-Smith, J. A., & Moon, B. J. (2002). Knowledge, teacher development and change. In Teachers’ professional lives (pp. 195–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Admiraal, W., & Saab, N. (2021). Teachers’ motivation to participate in continuous professional development: Relationship with factors at the personal and school level. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(5), 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Level | Count | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational stage where main duties are performed (greatest number of hours) | Early Childhood Education | 830 | 12.75 |

| Primary Education | 1910 | 29.33 | |

| Secondary Education | 3772 | 57.92 | |

| Gender | Female | 4560 | 70.02 |

| Male | 1855 | 28.49 | |

| Teaching experience at current educational level | Under 5 years | 1277 | 19.61 |

| 5–9 years | 955 | 14.67 | |

| 10–14 years | 710 | 10.90 | |

| 15–19 years | 1050 | 16.12 | |

| 20–24 years | 981 | 15.06 | |

| 25–29 years | 730 | 11.21 | |

| Over 30 years | 809 | 12.42 | |

| Type of school where you currently work | Public | 5634 | 86.52 |

| Subsidized | 680 | 10.44 | |

| Private | 198 | 3.04 | |

| Continuing Teacher Training Courses of +10 h over the last 6 years | None | 94 | 1.44 |

| 1–3 | 678 | 10.41 | |

| 4–6 | 1372 | 21.07 | |

| 7–9 | 1175 | 18.04 | |

| 10 or more | 3193 | 49.03 | |

| Ownership of the school where you completed your training for your teaching qualification | Public | 5512 | 84.64 |

| Private | 1000 | 15.36 | |

| Current position as a manager | Yes | 1611 | 24.74 |

| No | 4901 | 75.26 | |

| TOTAL | 6512 | 100 | |

| Items |

|---|

| Technical–Political scope |

|

| Teacher Training scope |

|

| Scientific–Academic scope |

|

| Technical–Political Scope | Teacher Training Scope | Scientific–Academic Scope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational stage where you perform your main work | Kruskal–Wallis test | 51.741 ** | 6.448 | 2.438 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Levels | Mean per item | Mean per item | Mean per item | |

| Early Childhood Education | 1.624 | 1.375 | 1.3025 | |

| Primary Education | 1.504 | 1.3625 | 1.26 | |

| Secondary Education | 1.436 | 1.33 | 1.2975 | |

| Levels | Technical–Political Scope | Teacher Training Scope | Scientific–Academic Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | ||

| Age | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | −0.012 | −0.024 | −0.016 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.079 | |

| Gender | Kruskal-Wallis test | 9.814 ** | 14.416 ** | 15.443 ** |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.023 | |

| Female | 1.60 | 1.35 | 1.28 | |

| Male | 2.07 | 1.79 | 1.70 | |

| Other | - | - | - | |

| Not answered | 1.6 | 1.25 | 1.42 | |

| Teaching experience in current position | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.050 | −0.019 | 0.018 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| Less than 5 years | 1.54 | 1.37 | 1.29 | |

| 5–9 years | 1.71 | 1.34 | 1.33 | |

| 10–14 years | 1.47 | 1.32 | 1.20 | |

| 15–19 years | 1.71 | 1.47 | 1.36 | |

| 20–24 years | 1.59 | 1.37 | 1.25 | |

| 25–29 years | 1.64 | 1.41 | 1.39 | |

| Over 30 years old | 1.70 | 1.30 | 1.31 | |

| Type of institution where currently employed | Kruskal–Wallis test | 12.636 ** | 8.344 * | 5.548 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.019 | 0.005 | 0.003 | |

| Public | 1.56 | 1.35 | 1.29 | |

| Subsidized | 1.85 | 1.48 | 1.39 | |

| Private | 1.77 | 1.41 | 1.26 | |

| Continuing Teacher Education | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.064 | 0.101 ** | 0.074 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.012 | |

| None | 1.97 | 1.22 | 1.38 | |

| 1–3 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 1.30 | |

| 4–6 | 1.54 | 1.29 | 1.28 | |

| 7–9 | 1.57 | 1.26 | 1.18 | |

| 10 or more | 1.67 | 1.47 | 1.37 | |

| Ownership of the institution where the qualifying degree was obtained | Mann-Whitney U test | 56,761.5 * | 45,572.5 | 43,779 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.002 | |

| Public | 1.60 | 1.35 | 1.29 | |

| Private | 1.70 | 1.46 | 1.36 | |

| Current management position | Mann-Whitney U test | 58,865 ** | 56,381 | 55,196 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.028 | 0.004 | 0.001 | |

| Yes | 1.78 | 1.43 | 1.33 | |

| No | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.28 |

| Levels | Technical–Political Scope | Teacher Training Scope | Scientific–Academic Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | ||

| Age | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | −0.002 | 0.005 | −0.016 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.031 | 0.028 | 0.031 | |

| Gender | Kruskal–Wallis test | 1.641 | 2.742 | 1.872 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Female | 1.50 | 1.35 | 1.26 | |

| Male | 1.53 | 1.39 | 1.26 | |

| Other | 1.4 | 2 | 1.25 | |

| Not answered | 1.32 | 1.29 | 1.13 | |

| Teaching experience in current position | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.038 | 0.047 * | −0.004 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.003 | |

| Less than 5 years | 1.43 | 1.30 | 1.33 | |

| 5–9 years | 1.49 | 1.33 | 1.23 | |

| 10–14 years | 1.52 | 1.39 | 1.28 | |

| 15–19 years | 1.58 | 1.42 | 1.28 | |

| 20–24 years | 1.49 | 1.41 | 1.26 | |

| 25–29 years | 1.49 | 1.30 | 1.22 | |

| Over 30 years old | 1.50 | 1.35 | 1.23 | |

| Type of institution where currently employed | Kruskal–Wallis test | 0.068 | 0.704 | 7.316 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | |

| Public | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.25 | |

| Subsidized | 1.50 | 1.39 | 1.36 | |

| Private | 1.52 | 1.40 | 1.38 | |

| Continuing Teacher Education | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.110 ** | 0.085 ** | 0.048 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.006 | |

| None | 1.33 | 1.13 | 1.35 | |

| 1–3 | 1.40 | 1.29 | 1.29 | |

| 4–6 | 1.44 | 1.34 | 1.25 | |

| 7–9 | 1.41 | 1.26 | 1.17 | |

| 10 or more | 1.56 | 1.41 | 1.29 | |

| Ownership of the institution where the qualifying degree was obtained | Mann–Whitney U test | 225,329 | 202,996 | 189,347.5 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| Public | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.27 | |

| Private | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.22 | |

| Current management position | Mann–Whitney U test | 309,870 ** | 291,601 ** | 279,433.5 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 1.60 | 1.44 | 1.26 | |

| No | 1.46 | 1.32 | 1.26 |

| Levels | Technical–Political Scope | Teacher Training Scope | Scientific–Academic Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | ||

| Age | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.012 | 0.052 ** | 0.031 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.009 | |

| Gender | Kruskal-Wallis test | 4.292 | 14.896 ** | 23.331 ** |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.007 | |

| Female | 1.43 | 1.31 | 1.26 | |

| Male | 1.44 | 1.37 | 1.36 | |

| Other | 1.69 | 1.57 | 1.66 | |

| Not answered | 1.28 | 1.2 | 1.27 | |

| Teaching experience in current position | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.046 ** | 0.108 ** | 0.055 ** |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.001 | |

| Less than 5 years | 1.40 | 1.28 | 1.28 | |

| 5–9 years | 1.43 | 1.28 | 1.29 | |

| 10–14 years | 1.42 | 1.31 | 1.31 | |

| 15–19 years | 1.43 | 1.36 | 1.30 | |

| 20–24 years | 1.47 | 1.41 | 1.32 | |

| 25–29 years | 1.44 | 1.32 | 1.27 | |

| Over 30 years old | 1.47 | 1.40 | 1.34 | |

| Type of institution where currently employed | Kruskal–Wallis test | 9.136 * | 21.379 ** | 2.980 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 | |

| Public | 1.42 | 1.31 | 1.29 | |

| Subsidized | 1.52 | 1.45 | 1.33 | |

| Private | 1.51 | 1.49 | 1.43 | |

| Continuing Teacher Education | Spearman’s Rank Correlation | 0.081 ** | 0.115 ** | 0.064 ** |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.006 | |

| None | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.29 | |

| 1–3 | 1.40 | 1.30 | 1.32 | |

| 4–6 | 1.36 | 1.24 | 1.24 | |

| 7–9 | 1.39 | 1.31 | 1.26 | |

| 10 or more | 1.50 | 1.40 | 1.34 | |

| Ownership of the institution where the qualifying degree was obtained | Mann–Whitney U test | 712,013 | 636,692.5 | 624,173 |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| Public | 1.44 | 1.33 | 1.31 | |

| Private | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.25 | |

| Current management position | Mann–Whitney U test | 790,576.5 ** | 712,811.5 ** | 784,657 ** |

| Size effect (eta2) | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 1.57 | 1.47 | 1.32 | |

| No | 1.41 | 1.30 | 1.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monarca, H.; Sánchez-Cabrero, R.; Pericacho-Gómez, J. Participation in Tasks Outside the Classroom and the Educational Institution of Non-University Teachers in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111528

Monarca H, Sánchez-Cabrero R, Pericacho-Gómez J. Participation in Tasks Outside the Classroom and the Educational Institution of Non-University Teachers in Spain. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111528

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonarca, Héctor, Roberto Sánchez-Cabrero, and Javier Pericacho-Gómez. 2025. "Participation in Tasks Outside the Classroom and the Educational Institution of Non-University Teachers in Spain" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111528

APA StyleMonarca, H., Sánchez-Cabrero, R., & Pericacho-Gómez, J. (2025). Participation in Tasks Outside the Classroom and the Educational Institution of Non-University Teachers in Spain. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111528