1. Introduction

The goal of the Indigenous Math Video Project is to bring back Ojibwe and Michif as the main language(s) for teaching and learning in the Turtle Mountain school systems and to revitalize Indigenous ways of knowing and doing mathematics. More specifically, the goal of this project is to develop a vast library of Ojibwe and Michif language videos aligned with K-12 STEM standards in North Dakota. This project was prompted by (1) our belief that math fluency and language fluency can develop together (

Luecke & Sanders, 2023), (2) the value of language acquisition principles within Indigenous language revitalization (

T. Hauff et al., 2024;

Hermes et al., 2012;

McIvor, 2020), and (3) support from the Turtle Mountain community. This project is an example of integrating Indigenous language revitalization principles within a school, beyond the language and culture classroom, in a very rural community currently without an immersion school. This project is based on previous research demonstrating that math and local language/culture integration strengthen student cultural identity and improve math exam scores (

Holm & Holm, 1995;

Lipka & Adams, 2004;

Lipka et al., 2007;

Kisker et al., 2012). This article focuses on the development and philosophy of the project, the first cycle of development, and the next steps.

1.1. Researcher Positionality Statement

One author, Marshall Asini-LaRocque, is from the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota. Throughout his life, Marshall had the privilege of working closely with Anishinaabe first-language speakers and knowledge carriers from his community and other Anishinaabe communities. Marshall has taught the Anishinaabe language, culture, and history across various settings from pre-K to college, camps, classes, and presentations. With roughly a decade of collaborating with first-language speakers, he has developed a skill set that supports language revitalization efforts in the community.

Halito. Immi hohchifo yvt Danny Luecke. Greetings. Danny Luecke grew up in Fargo, North Dakota. Boozhoo. Aaniin. Danny izhinikaazod. Fargo onjii. Gikenamagaa agindaasowinan omaa Mikinock Wajiw Gabe Gikendaaso Wigamig. We introduce him in the Choctaw language because he is a dual citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the United States. He also has ancestral and cultural ties to Scandinavia, Germany, and Ireland. He prays that he can honor all his ancestors and Creator in spirit and truth through this work. Danny completed his PhD in math and math education at North Dakota State University with a research focus at Sitting Bull College on Dakota/Lakota Math Connections. He currently works as a math and math education faculty at Turtle Mountain College.

1.2. Turtle Mountain Tribal History

The Turtle Mountain tribe has a rich and complex history. After the prophets came, one told the Anishinaabe to travel west and find “the food that grows on water”. Anishinaabe migrated from what is now the mouth of the St. Lawrence River around 900 AD. Anishinaabe people are spread across a vast area that stretches from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the great salt water of the east. Ojibwa, Ojibwe, Chippewa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Saulteaux, Menominee, Soto, and other terms are used to name groups of people who at one time came from the group known as the Anishinaabe. To this day, many of these tribes still recognize their ancestral name and refer to themselves as Anishinaabe.

As the Anishinaabe migrated west, they searched for “the food that grows on water”, known today as wild rice or, in the Anishinaabe language, manoomin. They found manoomin in what is now known as the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Ontario. From the woodlands, the Anishinaabe began to move further west. A group of Anishinaabe gravitated towards the plains in what is now North Dakota and Manitoba. By 1790, a new group, the Plains-Ojibwa, established a village in a place now called Pembina, North Dakota, located on the border of what is now Minnesota, North Dakota, and Manitoba. The core group who migrated to Pembina came from Ojibwe bands, including the Red Lake, Leech Lake, Pillager Band, Otter Tail Band, Mississippi Band, and others. From Pembina, the Plains-Ojibwa established villages from the Red River to the Rocky Mountains in places in North Dakota now known as Grand Forks, Pembina, Buffalo Lodge Lake, Stump Lake, Grahams Island, Rugby, Willow City, Turtle Mountain, Williston, Animoose, etc.

Some historical leaders of the Plains-Ojibwa were Taabaashaa, Old Man Wild Rice, Cottonwood, Black Duck, Red Bear, Young Man, Red Thunder, Little Shell I, Little Shell II, and Little Shell III. Those who know their history often refer to themselves as Turtle Mountain Pembina. Eventually, the Turtle Mountain band signed the

Old Crossing Treaty (

1862) and the

McCumber Agreement (

1892). These treaties affirmed the Turtle Mountain Band’s sovereign status and established a political relationship with the United States government (

Figure 1). Unfortunately, both of these treaties were negotiated under duress and have been contested in court numerous times.

In the mid-1800s, much of Turtle Mountain’s unceded land was occupied by immigrant squatters who were promised farmland by the U.S. government; land was also illegally seized by railroads. There were also numerous attempts to remove all Chippewa from Turtle Mountain. Chief Little Shell III fought to get land in reserve so his people would have a protected area that would be their home for time immemorial. After many years of fighting, in 1882, President Arthur drafted an Executive Order establishing the Turtle Mountain Reservation. Turtle Mountain originally included 20 townships; however, the inaccurate 1884 census led to a second Executive Order, which reduced Turtle Mountain to two townships and a 6 × 12-mile reservation. Little Shell III and others fought until their deaths to restore Turtle Mountain to its original size. Unfortunately, these lands were never restored. Today, Turtle Mountain has a population of roughly 35,000 and a reservation size of 6 × 12 miles, with over 400 acres of reservation land owned by non-natives.

In 2022, the Turtle Mountain Tribal Council passed a resolution for all schools operating within the reservation to promote language education for all learners of all ages (

TMBC, 2022). This resolution aligns with the mission of Turtle Mountain College (TMC), “in which culture, language, and social heritage of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa is integrated throughout the curriculum” (

TMC, 2025).

1.3. Turtle Mountain College History

In 1972, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians Tribal Council chartered Turtle Mountain Community College (recently renamed as Turtle Mountain College (TMC)) (see

Figure 2), making it one of the first six tribal colleges in the United States, marking the start of higher education in the Turtle Mountain community. Over the past 50+ years, the number of community members with higher education degrees has grown from just five to thousands. TMC recently celebrated the 25th anniversary of its Teacher Education Department.

1.4. Indigenous Math Video Project

The Indigenous Math Video Project (

Figure 3) began in Fall 2022 as we, the co-authors, discussed the intersection of language and math more regularly. Danny, who was working with local first-language speakers to help develop the Indigenous Math courses at the college, was seeking a way for language to be more integrated into not just the Indigenous math courses, but all math courses K-16 locally (

Luecke, 2023). The first math and language workshop was held in Summer 2023, beginning the first cycle of the project’s development. Support for this project is provided by the Turtle Mountain tribal government, Turtle Mountain Community Schools, and TMC.

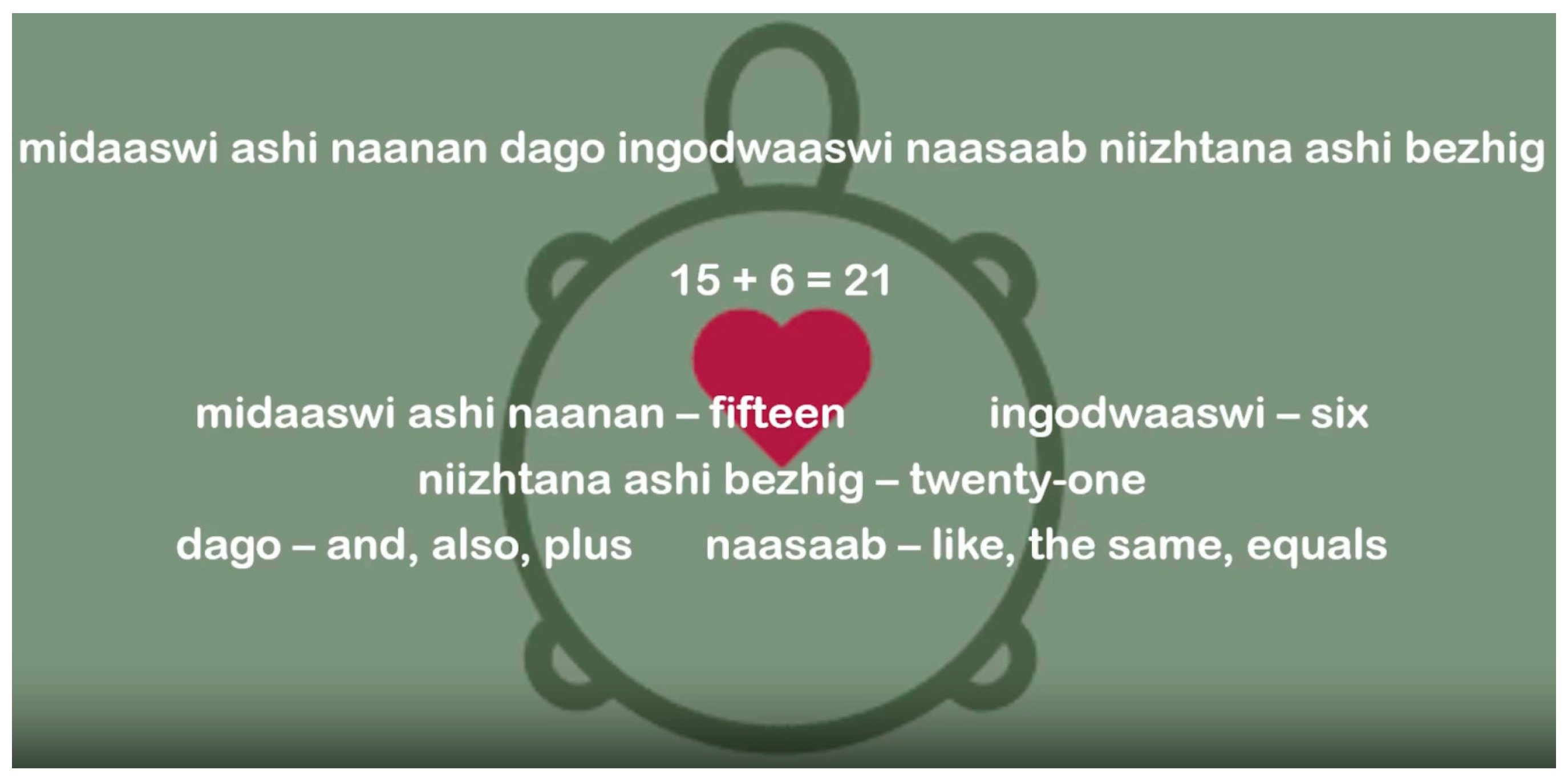

Figure 4 shows a screenshot of one of the first videos created for this project by Marshall. This video contained approximately one dozen slides with different addition equations. The video included both the Ojibwe and English languages. Based on feedback, this initial video was re-made during the second cycle of development.

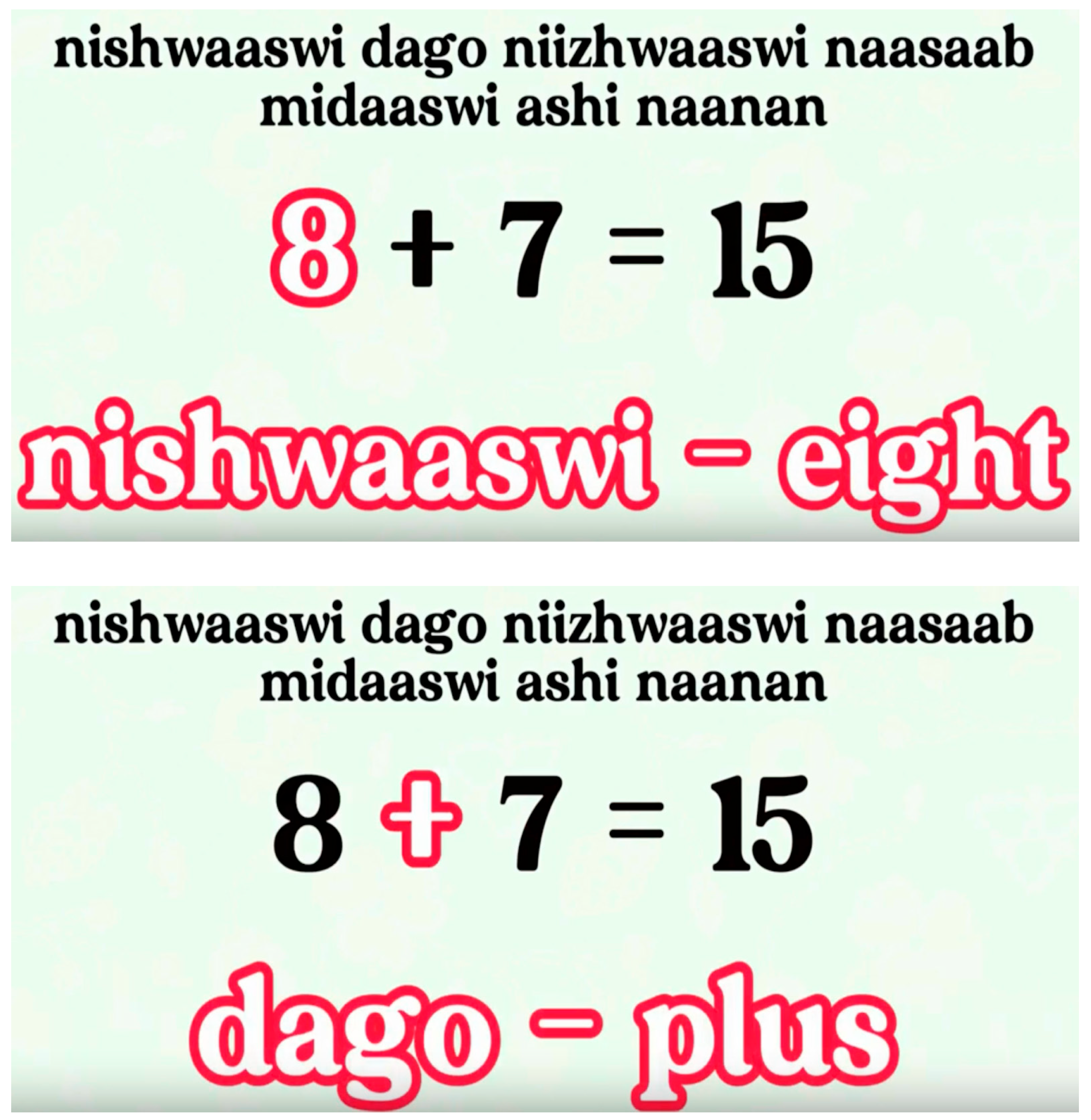

Figure 5 contains the first two screenshots of the redesigned video.

The first video example contains a collection of 12 addition-based equations, which is an early elementary math standard. Our goal is to cover math topics across K-16.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 address the use of language scaffolding for the simplest math topic, counting 1–10. Note that each video in the project has a specific level of math content, language content, and its own artistic style.

In sharing these video examples, it is important to point out that there are multiple ways in which to say an addition equation in the Ojibwe language and in English. These examples reflect our first attempts at video production working with first-language speakers in our Ojibwe community, and do not fully reflect the diversity of Ojibwe or Indigenous math. This is a philosophical tension we address further through this article.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods section shares the story of the Indigenous Math Video Project as well as how the feedback survey was developed, implemented, and analyzed. This storywork research applied to K-16 math education in the Turtle Mountains is based on an Indigenous research paradigm (

Archibald, 2008;

Kovach, 2009;

Wilson, 2008;

Windchief & San Pedro, 2019). According to

Kovach (

2009), “from a Nêhiýaw point of view, knowledge and story are inseparable, and that interpretative knowing is highly valued, that story is purposeful… [thus] Story as methodology is decolonizing research” (pp. 98, 103).

Windchief and San Pedro (

2019) expand on Archibald’s Indigenous storywork (

Archibald, 2008), writing:

Storywork practice is very different from Western commonsense notions of ‘universal stories,’ with presumed universal listeners and omniscient narrators who are never actually universal. In these stories, ‘universal’ means unmarked; perspectives that are often masculinist, conquering, and Eurocentric are normalized as gender-neutral, timeless, and placeless. By contrast, storywork makes transparent the listener and the teller.

Following these Indigenous researchers, we also emphasize story.

In doing this work, we also acknowledge the myth that math is ‘universal’ and culturally pure/neutral. Western math perspectives are mythologized to be pure, universal, and culturally neutral/superior (

Aikenhead, 2017,

2018;

Bishop, 1990;

Ernest, 2021;

Kawagley, 1997;

Medina et al., 2024;

Stevens, 2021;

Xu & Ball, 2024). In contrast, we use story work to show how Indigenous Math is place and community-based as well as language-specific. For example, the word Danny used for math in his Ojibwe introduction is agindaasowinan. This word stems from the verb agindaaso, which means s/he counts. Note how in Ojibwe the word for math is more verb-oriented in contrast to the noun-oriented and static English word for math. Within English (and Western paradigms), math is often only viewed as a noun, a thing, a chunk of specific knowledge. However, within an Indigenous math perspective and research paradigm, math is more verb-oriented, connected with the person doing it in a specific place. For example, the Ojibwe words for 2 and 7, 3 and 8 are niizh and niizhwaaswi, niswi and nishwaaswi, respectively. In a base 10 number system, notice the sub-base 5, where the suffix implies two/three on the other hand, for seven/eight. The language demonstrates that numbers are connected to one’s body, an embodied form of cognition (

Abrahamson et al., 2020).

Aikenhead (

2017,

2018) refers to this embodied cognition as ‘mathematizing’—thinking, doing, living, and being with the content.

Within an Indigenous research paradigm, knowledge represents a web of relationships amongst all of the cosmos (

Meyer, 2014;

Wilson, 2008). The same can be said of math, as a web of relationships amongst people, nature/land, language, and the entire cosmos (

Aikenhead, 2017,

2018). This relational approach to knowledge and math influences our research and writing. We view this project as a relationship with our community. As such, we are accountable to all our relations (

Meyer, 2014;

Wilson, 2008).

2.1. What Sparks Our Interest in and Excitement for Ojibwe Math?

2.1.1. Marshall’s “Spark” for Ojibwe Math

Historically, Turtle Mountain was a multilingual community, with individuals at one time speaking as many as nine languages and most fluent in at least four languages. However, due to forced assimilation through boarding schools, laws that banned Native languages and cultures, and other forms of systemic oppression, our once linguistically rich community has experienced a severe decline in language diversity. Today, all languages, except English, are endangered in Turtle Mountain, with only a few speakers of the traditional languages remaining. This reflects an alarming pattern of language loss, with only a few individuals presently achieving a level of fluency in the Ojibwe language.

The Ojibwe language has been formally included in the local school system since 1984. However, the instructional structure has remained largely unchanged. Culture classes have consistently followed the same schedule, two days per week for thirty minutes per session, with varying degrees of integration of the Ojibwe language. This stark reality highlights the effects of historical oppression and how the persistent forced influence of Euro-Western ideologies has reshaped our understanding of what we deem as “important” in education. As a result, language and culture are often relegated to an elective status and treated as non-essential areas of study, while other subjects are prioritized over the history, language, and heritage of the Tribe. The cultural hegemony that has been deeply ingrained within the community by numerous oppressive actions reinforces the false notion that placing too much emphasis on our own Tribal history, culture, and language will somehow hinder students’ success in areas deemed more “valuable” by the dominant educational system. This mindset continues the very erasure that colonial policies set in motion, further disconnecting their community from its cultural and linguistic heritage.

Throughout the years, there have been numerous attempts at finding effective ways to integrate language more meaningfully into education. Generally, these efforts have been short-lived, while occasionally some efforts show greater commitment and longevity. In 2022, a professional development initiative aimed at strengthening the integration of the Anishinaabe language and culture within local schools. This initiative emphasized helping educators incorporate Indigenous language and cultural knowledge into daily classroom instruction, ensuring that students can engage with their culture and language in a meaningful and consistent way. Rather than treating language and culture as isolated components of the curriculum, as they historically have been, our goal was to demonstrate how language and culture could be naturally woven into existing lesson plans, fostering a more immersive and enriching educational experience for students. By collaborating directly with educators, an effort was made to provide them with the tools, resources, and confidence needed to bring Anishinaabe language and cultural teachings into their classrooms in a way that was both sustainable and impactful.

As part of this initiative, a team was tasked with creating and presenting content across multiple academic areas to support educators in integrating the language into their classrooms. A key focus area, developed in close collaboration with first-language Anishinaabe speakers, was mathematics. In the early stages of designing an Ojibwe-language math curriculum, emphasis was placed on foundational arithmetic concepts—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—specifically tailored for beginner-level learners. The goal was not only to teach mathematical skills but also to ensure students could engage with these concepts through an Anishinaabe lens, thereby reinforcing both numeracy and language acquisition in a holistic and meaningful way.

During the professional development training, a local teacher shared that teachers could incorporate videos into their curricula and use these videos as instructional tools in the classroom. This insight sparked the idea that perhaps one way to effectively support our local schools and community would be to develop educational videos focused on various subjects, integrating the Anishinaabe language in a way that could become a lasting part of the curriculum. By doing so, we could potentially significantly increase students’ daily exposure to the language in areas outside of language and culture classrooms.

This professional development initiative focused on how to create better paths for language inclusion in the overall curriculum of schools. In response to the lack of teachers in Turtle Mountain who speak the Ojibwe language, one promising idea was to develop videos that showcase lessons in a target area of study. These videos could then be incorporated into the curriculum. Over the past few summers, we have had multiple sessions with numerous first-language speakers of the Anishinaabe language to develop various areas of math in the Ojibwe language.

2.1.2. Danny’s “Spark” for Ojibwe Math

Danny’s spark for Ojibwe math began when he was hired at TMC in Fall 2021 to develop a bachelor’s degree program in Secondary Math Education. Danny’s belief in emphasizing Indigenous math that is place-based and language-specific emerged from his experiences with the Wahóȟpi Kiŋ (the Lakota Language Immersion Nest) at Sitting Bull College and the D/Lakota Math Connections project (

Luecke, 2025a;

Luecke & Sanders, 2023). When developing the bachelor’s degree program at TMC, Danny knew that an Indigenous Math sequence needed to be a priority, but he could not develop this sequence on his own. First-language speakers and local elders/knowledge keepers needed to be involved. In the spring of 2022, Danny met regularly with Cecelia Myerion and Velda Belgarde, two first-language speakers, elders, and language instructors at TMC. Myerion and Belgarde greatly influenced Danny, both personally and in the development of the Indigenous math courses, which were named Agindaasowinan Bezhig, Niizh, and Niswi (Ojibwe Math I, II, and III) (

Harris, 2002;

Luecke, 2023,

2025b).

Marshall and Danny met in Fall 2022 and immediately began discussing language/acquisition as they learned from multiple first-language speakers working at TMC, including Corrine and Morris Houle. Danny and Marshall both wanted to see language learning not just solely in the culture classroom, but throughout the curriculum and community. Danny specifically wanted to see language learning in the K-12 math classroom. Marshall shared the idea of language-focused videos with Danny, and their collaboration began.

2.2. Approaching This Work with Caution

There are several benefits of combining the teaching of language and math through the use of videos. First, videos provide proper pronunciation from first-language speakers, which is invaluable for language learners. Second, videos do not require math teachers to be language experts. Rather, math teachers can learn language alongside their students. Further, the development and use of the videos allow required math topics to be introduced in the community’s traditional language(s). Third, immersion nests are a great approach for language revitalization (

Hermes, 2007;

McCarty & Nicholas, 2014); however, this has not yet become a reality in Turtle Mountain. As such, language videos that could be played daily in all K-12 math classrooms seemed like a positive, doable option to increase language exposure. Language videos aligned with K-12 math standards, scaffolded both in math content as well as language, allow language learning to happen throughout the school day and not simply in the language and culture classroom. The development and use of videos is one step towards Ojibwe (and Michif) becoming the medium for instruction throughout Turtle Mountain schools.

However, Danny’s experience with Wahóȟpi Kiŋ at Sitting Bull College made him cautious of the colonizing tendencies in language revitalization efforts, described by

Battiste and Henderson (

2000) as “the illusion of benign translatability” (pp. 80–83), that languages can be translated directly and fully (one-to-one translation). This illusion is based on the colonizing myth of a universal worldview and universal perspective of language and grammar that is actually Eurocentric (

Battiste & Henderson, 2000;

Mellow, 2015). The danger of the illusion of benign translatability is intensified within the U.S. education system, where many Indigenous scholars confirm that colonizing education still dominates (

Brayboy et al., 2015;

Cajete, 1994;

Deloria & Wildcat, 2001;

McCarty & Lee, 2014;

Smith et al., 2018). Claiming a culturally neutral education system only strengthens the myth of Western culture as normal and/or superior.

This danger is further intensified within math and the overarching colonizing mythology of Western math as pure, universal, culturally neutral, and superior to culture (

Aikenhead, 2017,

2018;

Bishop, 1990;

Ernest, 2021;

Kawagley, 1997;

Medina et al., 2024;

Stevens, 2021;

Xu & Ball, 2024). This myth is exemplified in phrases such as “2 + 2 = 4 everywhere” and “math is universal”.

Bishop (

1990) describes the widespread belief and implementation of Western math as pure and superior to culture in government, business, and education as “the secret weapon of cultural imperialism.” In fact, Indigenous math is unique and diverse to each place and language. “Given the existing ecological diversity, a corresponding diversity of Indigenous languages, knowledge, and heritages exist” (

Battiste & Henderson, 2000, p. 41). Even with these significant dangers, we remained excited about the opportunity for students to hear the Ojibwe language on a regular basis in the classroom.

2.3. Language Acquisition Research Within Indigenous Language Revitalization (ILR)

An essential aspect of language development is connective speech, which refers to the natural flow of words in spoken language (

Bi et al., 2022). Sounds often blend or change when spoken, and these subtle shifts are not always reflected in written language. Without exposure to Native speech, learners will likely not have exposure to these sounds. In Anishinaabemowin, for example, “Mikinaak Wajiw indoonji” (meaning “I come from Turtle Mountain”) is typically pronounced more fluidly as “Mikinaak-kwajiw Ind-doonji.” The added sounds that emerge in speech are a natural part of the language, but are not represented in the written form of the language at all. If students only learn individual words from books or word lists or do not have access to a speaker who makes the sounds of connective speech, they miss the critical exposure to the natural rhythm and connected sounds of fluent speech. This is why incorporating first-language Anishinaabe speakers into learning is vital, so learners can hear and develop a more authentic understanding of the language (

Bi et al., 2022;

Rouvier, 2017).

A key factor in creating materials that enhance language learning is language acquisition—the process of naturally acquiring a language through exposure to its use. There are many ways to acquire a language, including videos, audio recordings, books, audiobooks, translation exercises, and language immersion. Making language acquisition more effective means ensuring the content is understandable for learners. This varies depending on age and learning preferences, but generally, the easier language resources are to understand, the easier it is to learn (

S. Krashen, 1989;

S. D. Krashen, 2003).

Another crucial element is engagement. If learners are not motivated or interested, language acquisition will be less effective (

S. Krashen, 2004). In Turtle Mountain, we have applied these concepts to develop new ways of making language accessible, as evidenced in the video project.

Lastly, within the last five to 10 years, ILR has begun to ask the question, “Did they become more proficient?’ (

Green, 2017). Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for a language and culture class to focus on Indigenous identity or high-level spiritual thoughts taught in English. Not that this approach is wrong or bad, but it does not necessarily lead to language fluency. This tension is further compounded by the question of what math content will be focused on. This also raises the question of whether or not to teach Western math or one’s own cultural math, even when cultural math may not be used regularly.

2.4. Development Cycle for the Indigenous Math Video Project

The Development Cycle for the Indigenous Math Video Project has three main components or phases (

Figure 9), beginning with first-language speakers discussing and determining math vocabulary in Ojibwe (and Michif). From this vocabulary, Marshall and Danny, along with multiple student interns at TMC, worked to create videos that align transcripts, worksheets, and online assessments. Audio is developed directly by first-language speakers or second-language speakers who feel confident enough to be recorded. Videos and curriculum are implemented by teachers in local schools or by families at home. Feedback on the videos, math content, and language acquisition experience is collected to strengthen the next phase of the development cycle.

The value of the development cycle has not been solely in the three-phase cycle. Rather, much of the value has been in the development of a visual aid that can be shared with everyone involved in the project. This visual allows them to see the big vision and where they fit in. First-language speakers can see that their work on determining vocabulary will be implemented in the local schools. Student interns at TMC can see where the transcripts and audio come from and that their work will also be implemented into the local schools. Teachers and students see where these videos are developed and how their feedback influences the next development cycle. College administrators, Turtle Mountain Community Schools administrators, and the Turtle Mountain Tribal Council can see their crucial role in supporting the project financially and in other ways. The development cycle also allows our team to demonstrate where certain funds are being spent. Lastly, the development cycle allows our team to share the big vision of the project while simultaneously giving practical, small steps that everyone in the community can take. Altogether, the development cycle has allowed us to balance community relationships more easily.

2.5. Summer Math and Language Workshops

The first Ojibwe math and language workshop was held in Summer 2023 at Turtle Mountain College. The first Michif math and language workshop was held in Spring 2024 at the home of two first-language speakers. Summer language workshops gave us the opportunity to sit with first-language Anishinaabe (or Michif) speakers who could guide our language development efforts. Some sessions were recorded for inclusion in video lessons, ensuring that the authentic sounds of the language are accurately represented.

During these workshops, speakers shared their invaluable input with hundreds of written examples of how they naturally speak. They were given full control over the final translations, ensuring that natural speech patterns were preserved. This is a crucial step in language acquisition, as exposure to authentic language input directly influences how learners develop fluency. If the language input is not authentic or viable, learners’ speech will likely be affected, leading to unnatural or inaccurate usage. This is a common issue when there are no fluent speakers involved in the teaching process or when instructors lack proficiency in the language. By developing Anishinaabe language resources in collaboration with native speakers, we ensure that learners receive high-quality, authentic input, setting a strong foundation for accurate language acquisition and accurate language use in the future.

2.6. Video/Curriculum Development

Videos provide a unique solution to a common challenge faced by communities working to revitalize their language. They serve as a valuable resource, allowing learners to hear the language while also providing varying levels of comprehensible input. However, to navigate some of the dialect distinctions and varying approaches to language acquisition within Indigenous language revitalization, the following language note is placed at the end of each video: “Anishinaabemowin (the Ojibwe language) is a rich, diverse language passed down orally for generations. There is no single, superior way to communicate these ideas, both in vocabulary and pronunciation. This video and entire project are simply one approach to growing language fluency and math fluency together.”

From the beginning, we recognized that our initial videos might not be of the highest quality. However, as we continue to refine our skills and improve production, our focus remains on creating engaging, high-quality content that captures the attention of learners. More importantly, we understand that the first step is to begin working toward the shared goal of developing effective resources that support language revitalization.

Videos also play a crucial role in bringing language revitalization to spaces where it might not otherwise exist. In places where there are no fluent speakers available to teach, videos provide a viable way to incorporate the language. They also help reduce the intimidation often associated with language learning, making the process more accessible and approachable for learners.

In these first years of the project, we have naturally started with the low-hanging fruit, that is, beginning with the simplest, easiest videos to make. Often this means more straightforward Ojibwe and Michif vocabulary terms, such as numbers, as well as more basic math concepts, such as numbers, counting, and addition. Our next step is towards subtraction, multiplication, and fractions, and the big vision for me (Danny) is to eventually get to secondary math topics/standards.

Along with naturally beginning with the low-hanging fruit, video creation had a general focus on balancing relationships. For example, student interns each brought their own creative style(s), and we did not want to hamper that. Rather, if a variety of styles could be developed, it might prompt learners to ask ‘what will the next video be like?’ Our goal was to develop videos that were entertaining for both young kids and adults, sort of like many Disney movies. Further, we wanted to balance the relationships/roles of the many people involved, including student interns’ creative style, first-language speakers, school districts (admin and teachers) requests, and community involvement (in general and from tribal council), as well as language acquisition principles.

Originally, the videos were posted on Google Drive and made available through a shared link. However, after Cycle 1, in preparation for Cycle 2, student interns upgraded our tech delivery to our website—

www.indigimath.com (accessed on 31 October 2025) See

Figure 10.

2.7. Implementation and Feedback

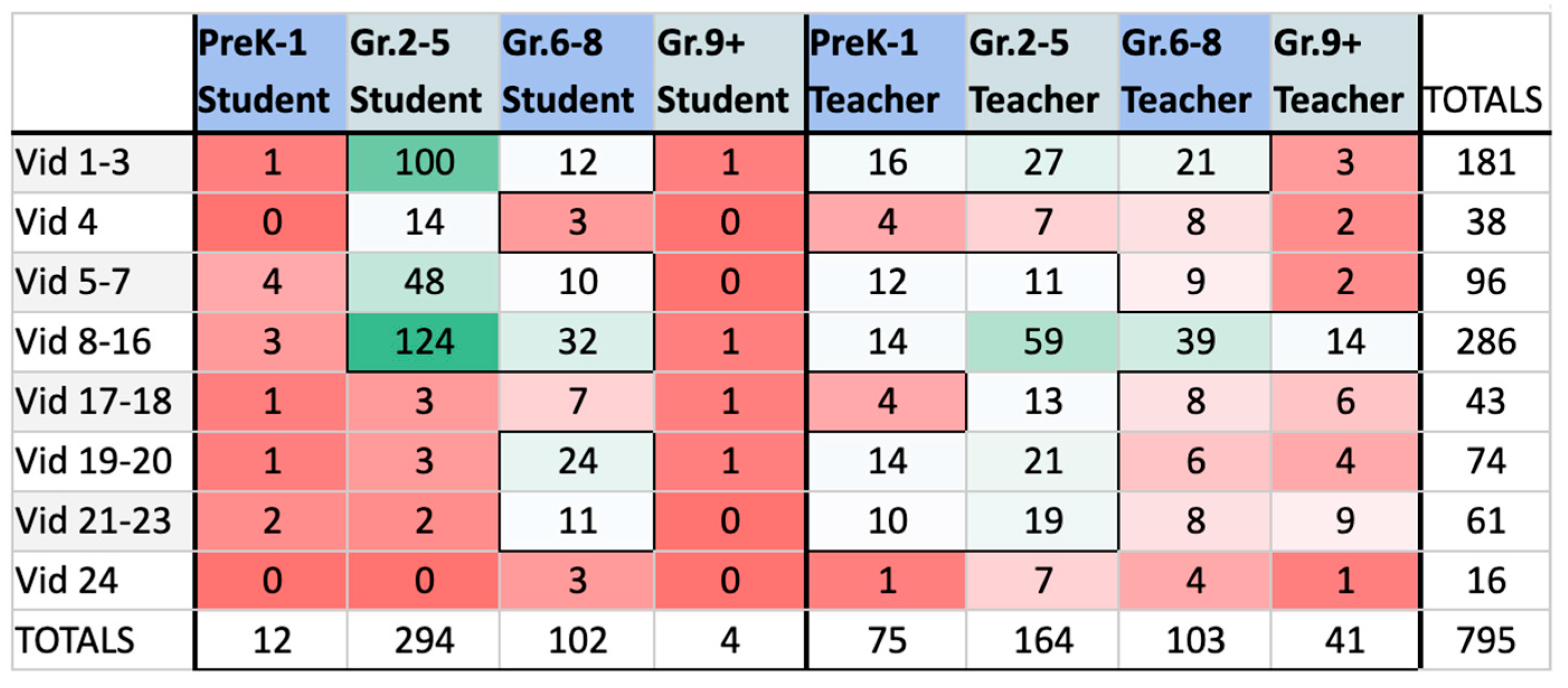

The first major round of implementation and feedback occurred in Fall 2023. Approximately 30 local K-12 educators were taking Ojibwe language courses at TMC during their personal time with a small stipend from Turtle Mountain Community Schools. Through these courses, local educators were encouraged to play videos in their classrooms and have both their students and themselves provide feedback through the teacher or student survey. Additionally, 12 pre-service teachers taking the course MATH 172 (Indigenous Math I) were encouraged to play the videos for students in their lives, whether at home or through some school activity.

2.8. Feedback Survey Development

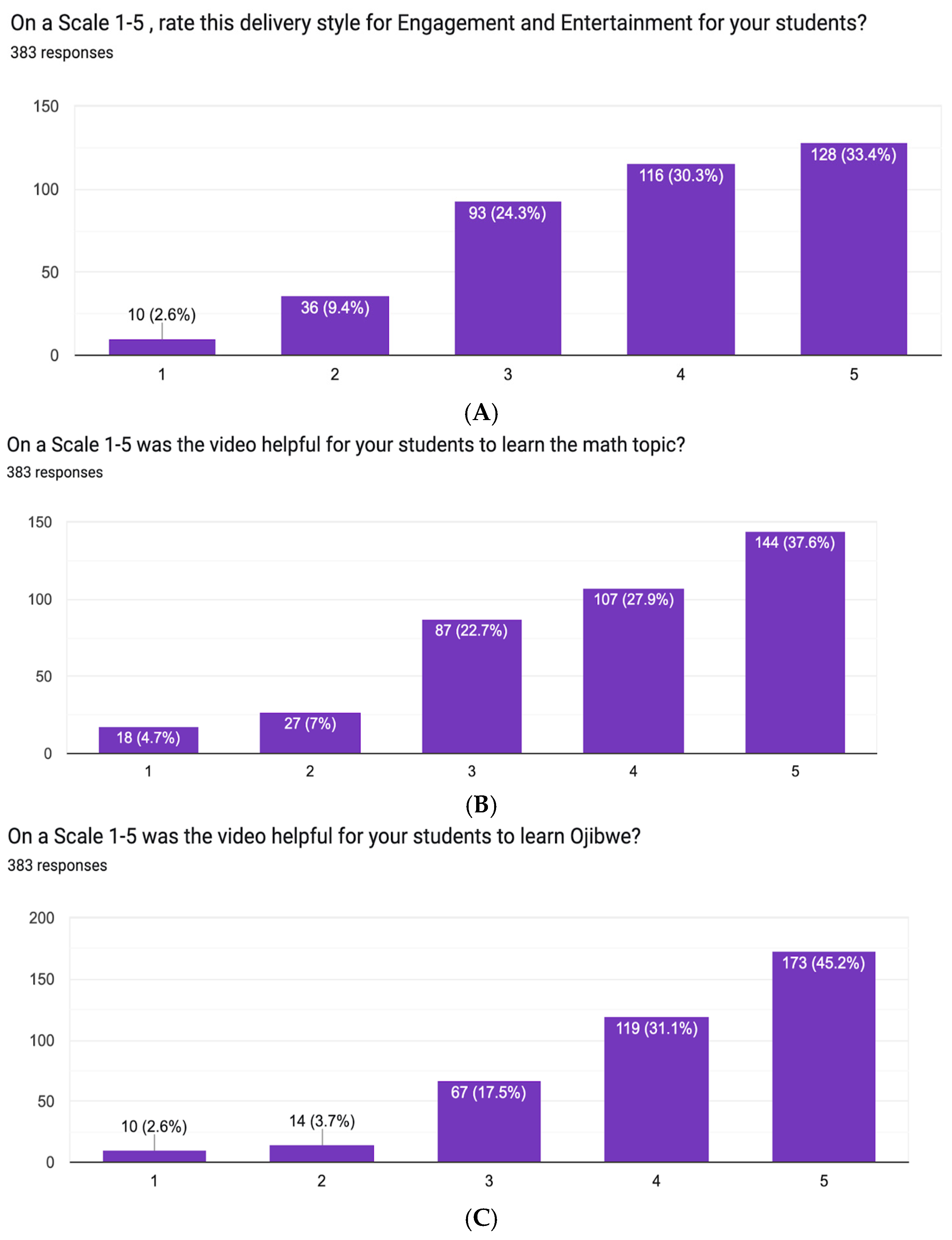

The goal of the feedback survey was to gain qualitative and quantitative responses from students and teachers. As shared previously, a core idea behind this project is that math fluency and language fluency can grow together. To assess both learning the Ojibwe language and math topics over multiple grade level standards, we developed a self-perception instrument. This instrument aligns well with the language acquisition principle, which holds that the more enjoyable and engaging the material is, the more naturally language acquisition occurs (

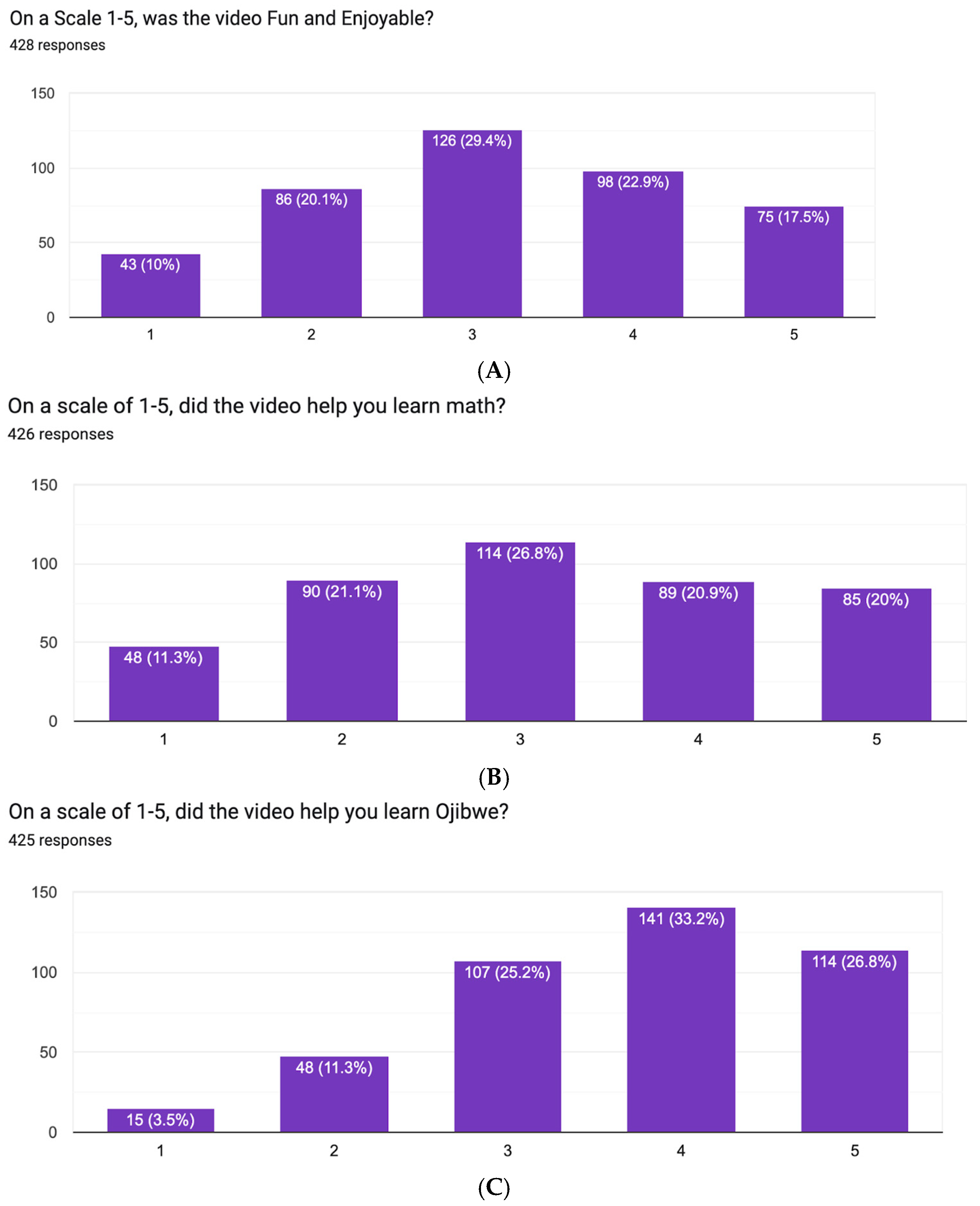

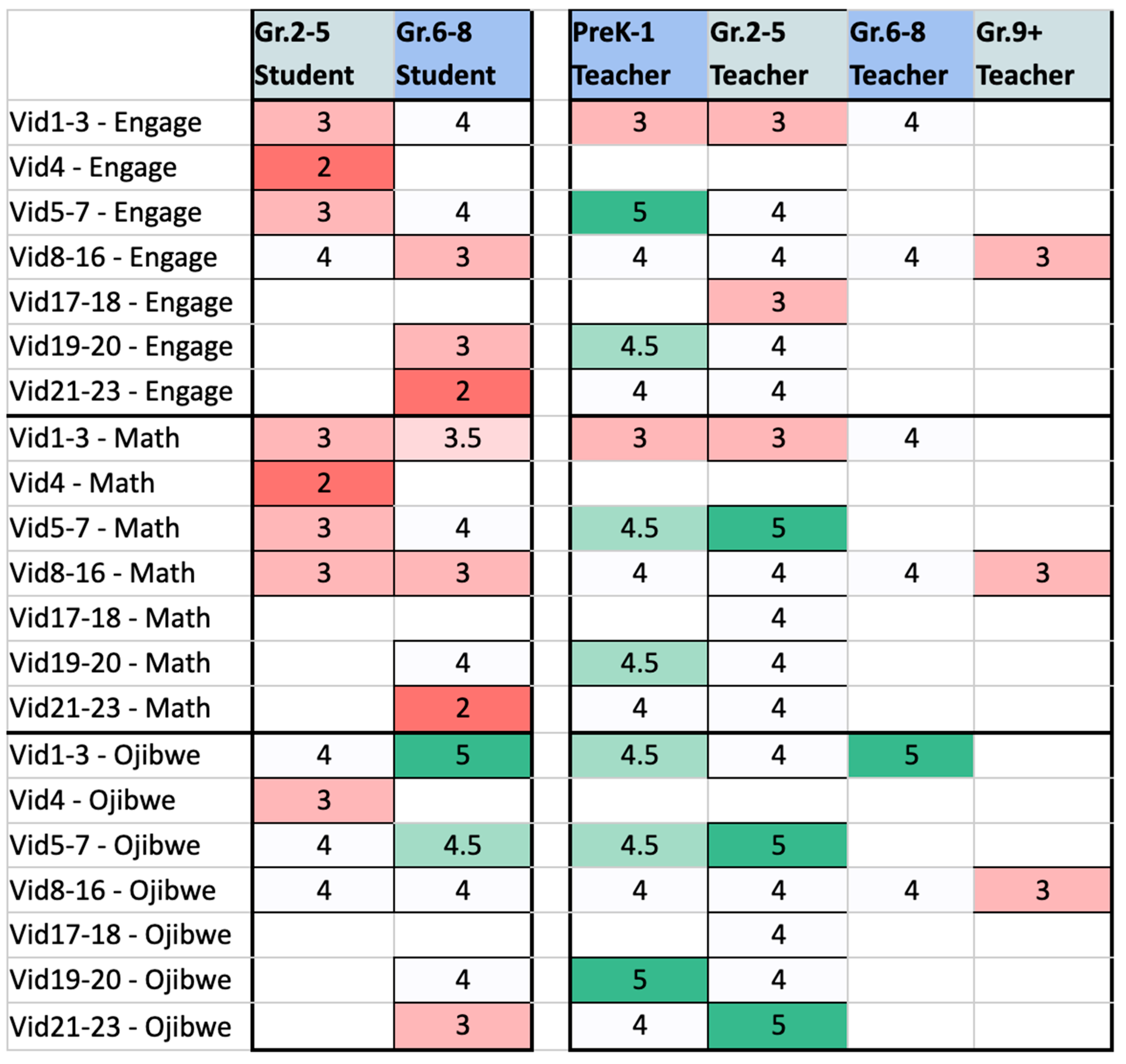

S. Krashen, 2004). This instrument assessed self-perceived value in math learning, value in Ojibwe language learning, and engagement for the students. We predicted that not only students and teachers might have different responses, but that they would vary across grade levels. Further, the videos had a variety of focal points—from different math topics and vocabulary, as well as some videos that were more math or language focused.

A shorter (fewer question prompts) and simpler (fewer ‘short answer’ questions) version of the instrument was developed for students as young as early childhood. A slightly longer (with multiple ‘short answer’ questions) instrument was developed for teachers (as well as parents and/or community members). The teacher survey was designed to be completed in less than two minutes, focused on teacher perceptions of the student(s) they watched the video with.

4. Discussion

The results of this study support the continuation of this project. While students and teachers appreciated the videos, they also provided constructive feedback. Results also support the continued use of the feedback survey, with distinctions between student/teacher, grade level, video theme, and the three categories of study (engagement, math, and Ojibwe language).

The initial (and follow-up) analysis provided guidance for the second cycle of development. In response, the following revisions were made in Cycle 2.

Attempted to have multiple speakers per video to slow down pacing while keeping/increasing engagement.

Added more visuals/animations throughout the video to increase engagement. To accomplish this, more TMC student interns were hired and given Pro accounts on Canva with its vast library of graphics. Student interns were/are encouraged to bring their own creative style to their videos. Further, this builds capacity for more language efforts in the community (

McCarty & Nicholas, 2014).

Increased audio quality through a better microphone (Yeti snowball mic) and open-access software for audio called Audacity. Ensured each video has background music at a quiet volume for increased engagement while keeping pronunciation clear.

Videos were moved from Google Docs (with links) to our website

www.indigimath.com (accessed on 31 October 2025).

To better align videos with grade levels, the order of the videos was changed from order of creation (Cycle 1) to order by age appropriateness (Cycle 2 and beyond). This allows simpler videos to be shared earlier and more challenging math and language videos to be shared later on in the webpage. Further, North Dakota grade-level math content standards are displayed near each video. This does not account for the spectrum of language complexity a video could have; however, this is a step forward in increasing age-appropriateness. This also encourages math teachers to use videos near specific grade levels for specific standards.

Worksheets were added for each video; however, due to time constraints, they are not as high-quality as desired.

Formative assessments were added for each video, and summative quizzes for each theme of videos. Assessments most often include matching vocabulary words and math exercises in the Ojibwe language (

Wong et al., 2025).

To increase engagement within the community more broadly, we developed Michif math videos. Turtle Mountain is a multilingual community; therefore, community impact/engagement is increased through involving both the Ojibwe and Michif languages.

We plan to recommend professional development to teachers regarding the implementation of the language-math videos within the classroom.

At the writing of this article (Spring 2025), Cycle 2 has been completed, and the project is entering Cycle 3 of development. Long-lasting impacts of this study continue. Specific comments continue to guide the efforts of Cycle 3. For example, Cycle 3 videos will include more math-specific visuals, such as dot patterns for addition problems and arrays for multiplication. Further, key Ojibwe/Michif words will be reviewed at the end of each video to review the language component. Throughout future videos, practical classroom instruction vocabulary will be used, in addition to math terms. Further, local K-12 teachers and students will be included in the video development process itself. Two areas appear promising for future research, including interviewing students, teachers, and language speakers, as well as evaluating how certain videos and accompanying activities impact math and language learning. Overall, for this project, our goal continues to be a step towards multilingual math education, and education broadly, in the Turtle Mountains.

Navigating Challenges in Indigenous Language Revitalization

The IndigiMath Video Project attempts to navigate key challenges in Indigenous Language Revitalization (ILR) by providing community-supported math classroom language videos to strengthen both language and math learning, a more holistic approach to education (

Hermes & King, 2013;

Hermes et al., 2012;

Luecke & Sanders, 2023;

McCarty & Nicholas, 2014;

McIvor, 2020;

Meighan, 2021). Traditional language instruction in K-12 settings has often focused on rote memorization and vocabulary lists. This approach stems from systematic colonization and a lack of consistent financial resources and has resulted in limited Indigenous language proficiency (

Greymorning, 1997;

T. R. Hauff, 2020). The IndigiMath videos, however, allow students and teachers to hear the language spoken within math contexts. Math teachers can learn the Ojibwe language with their students, reducing the burden on math teachers to be the language/culture expert when integrating local knowledge into their classrooms. Research demonstrates that successful ILR efforts emphasize community-centered approaches, technology-driven resources, and immersive language environments (even outside of immersion programs) spanning across school-based (pedagogy) and community-based (andragogy) efforts (

Green, 2017;

Hermes & King, 2013;

Hermes et al., 2012;

McCarty & Nicholas, 2014;

McIvor, 2020;

Meighan, 2021). Even though the videos are designed for school use, they are available to the community. This project’s focus on language videos in math classrooms not only enhances language accessibility outside of the language and culture classroom but could also lead to social and cultural resurgence in the community, which is central to ILR (

T. R. Hauff, 2020;

T. Hauff et al., 2024;

Hermes & King, 2013;

Hermes et al., 2012;

McCarty & Nicholas, 2014;

McIvor, 2020;

Meighan, 2021).

5. Conclusions

This article shared the story and pilot year/cycle of development of the Indigenous Math Video Project. In the discussion, some of the major lessons learned that came from the data analysis for future cycles of the project were shared, as well as the major difficulties encountered. No curriculum is perfect, and this project is no exception. Rather, this project follows from the desire for Indigenous Language Revitalization in Turtle Mountain. This project has the opportunity to strengthen tribal sovereignty by not depending on large, outside education companies to provide a curriculum for the community. Prior research also demonstrates that when math and local language/culture are integrated, both exam scores increase and identity is strengthened (

Holm & Holm, 1995;

Lipka & Adams, 2004;

Kisker et al., 2012;

Lipka et al., 2007). Videos allow students, teachers, and community members to hear the language spoken, allowing for more comprehensible input.

This line of research responds to the ongoing need for projects and studies integrating language/culture into all subject areas in K-12 schools, not just language classes separated from the rest of the school and community. Furthermore, this research begins to refine our theory on engaging, accessible, relevant, and effective language instruction in K-16 STEM classrooms. We dream of making videos for every classroom in K-16 school systems such that students, community members, and adult learners want to keep watching Ojibwe/Michif math/science videos, and are asking, “What can I watch next?” This is an important step towards Indigenous Language Revitalization in Turtle Mountain and the strengthening of students’ math fluency. Learning math in one’s own Indigenous language(s) can strengthen mathematical learning as well as one’s relationship with self, community, ancestors, and future generations.