Is Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula Associated with Children’s Literacy Gains and Are Associations Moderated by Risk Status, Receipt of Intervention, or Preschool Setting?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Curricula in Early Childhood Education

1.2. Skills-Focused Curricula Compared to Non-Skills-Focused Curricula

1.3. Literacy-Focused Curricula

1.4. Child Risk Status, Emergent Literacy Intervention, and Preschool Settings as Moderators

1.5. The Current Study

- To what extent do preschool teachers report using literacy-focused curricula in their classrooms, and what specific literacy-focused curricula do they report using?

- Is the use of literacy-focused preschool curricula, compared to not using literacy-focused curricula (e.g., emergent, comprehensive, or whole-child approaches), associated with greater gains in print and letter knowledge, phonological awareness, language and comprehension, and emergent writing skills for preschool children?

- Is the association between use of literacy-focused curricula and preschool literacy gains moderated by child risk status, receipt of early literacy intervention, or program settings?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Classrooms and Teachers

2.1.2. Preschool Children

2.2. Planned Missingness Design

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Classroom Curriculum

2.3.2. Child Outcome Measures

2.4. Moderator Variables

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Analytic Approach

2.6.1. Missingness

2.6.2. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Reported Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula by Preschool Teachers

3.2. Associations Between Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula and Emergent Literacy Gains

3.3. Moderating Roles of Child Risk Status, Receipt of Early Literacy Intervention, and Preschool Settings

4. Discussion

4.1. Preschool Curriculum

4.2. Literacy-Focused Curricula and Children’s Gains

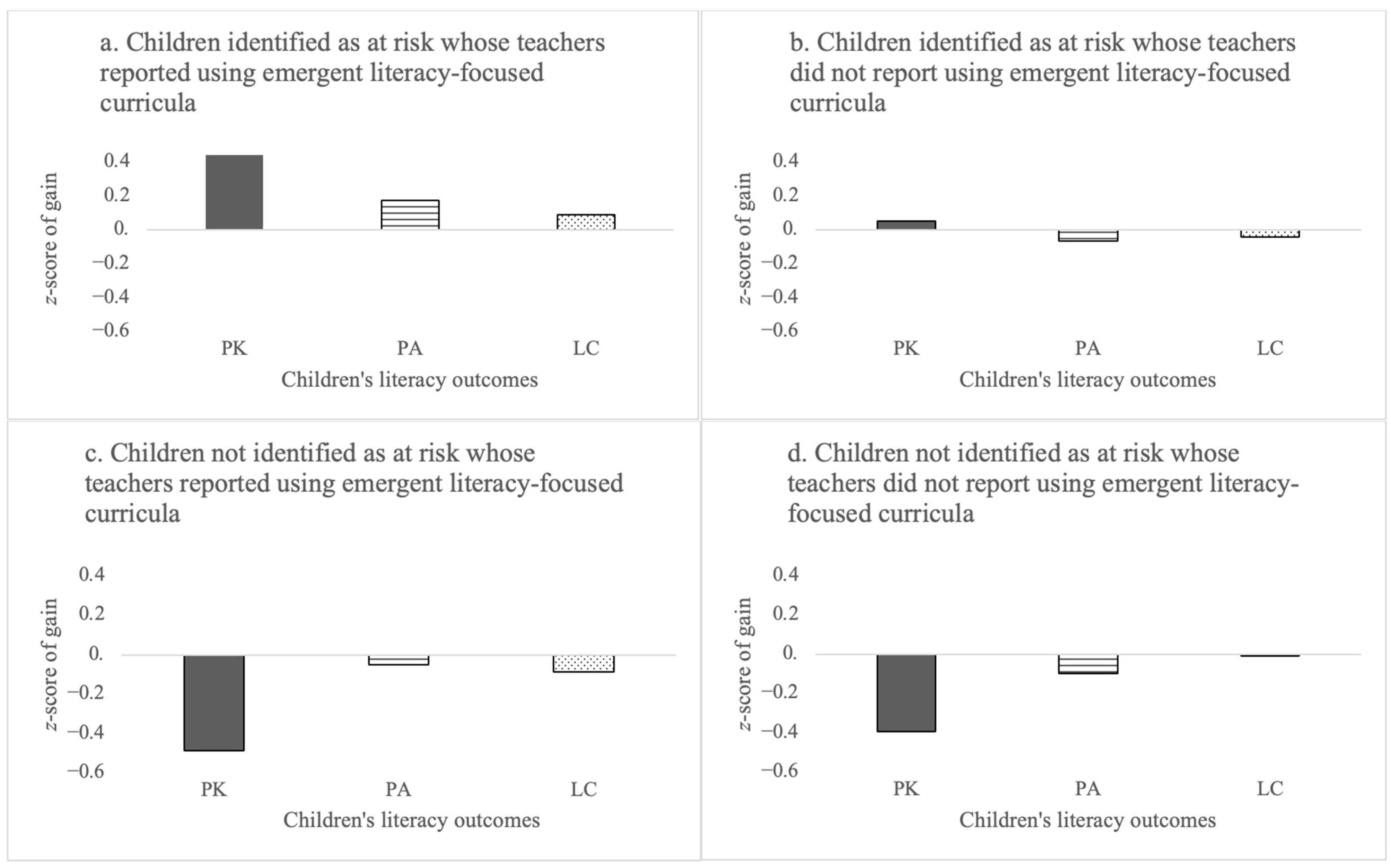

4.3. Better Gains for Literacy-Focused Curricula for Children at Risk for Later Reading Difficulties

4.4. Similar Gains for Children Not at Risk Regardless of Curricula

4.5. Additional Findings

4.6. Limitations and Conclusions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Of the 571 children included, 395 (69.2%) received the literacy intervention and 176 (30.8%) did not. Of the 395 intervention recipients, only 44 (11.1%) were in classrooms using a literacy-focused curriculum. |

References

- Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, M. K., Reed, S., Dickinson, D. K., Morse, A. B., & Wilson, S. J. (2009). Opening the world of learning: Features, effectiveness, and implementation strategies. Early Childhood Services: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Effectiveness, 3(3), 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (2007). Increasing young low-income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 107(3), 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, G. E., Quinn, M. F., & Gerde, H. K. (2017). Examining early childhood teachers’ writing practices: Associations between pedagogical supports and children’s writing skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 39, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, R. P., Justice, L. M., Khan, K. S., Piasta, S. B., Skibbe, L. E., & Foster, T. D. (2020). Development of the narrative assessment protocol-2: A tool for examining young children’s narrative skill. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(2), 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal, M., Whitaker, A. A., & Jenkins, J. M. (2022). The promise and purpose of early care and education. Child Development Perspectives, 16(3), 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M., Zaslow, M., Tarullo, L., Votruba-Drzal, E., & Miller, P. (2016). Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Secondary data analyses of child outcomes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Piasta, S. B., Curenton, S. M., Wiggins, A., Turnbull, K. P., & Petscher, Y. (2011). The impact of teacher responsivity education on preschoolers’ language and literacy skills. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(4), 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabell, S. Q., Kim, J. S., White, T. G., Gale, C. J., Edwards, A. A., Hwang, H., Petscher, Y., & Raines, R. M. (2025). Impact of a content-rich literacy curriculum on kindergarteners’ vocabulary, listening comprehension, and content knowledge. Journal of Educational Psychology, 117(2), 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S., & Barnett, W. S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teachers College Record, 112(3), 579–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, J. J., Greenwood, C. R., Goldstein, H., McConnell, S. R., Kaminski, R., Bradfield, T. A., Wackerle-Hollman, A., Linas, M., Guerrero, G., Kelley, E., & Atwater, J. (2016). Advances in Multi-Tiered Systems of Support for Prekindergarten children: Lessons learned from 5 years of research and development from the center for response to intervention in early childhood. In Handbook of response to intervention. Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetti, G. N., Fitzgerald, M. S., Hiebert, E. H., & Hebert, M. (2023). Meta-analysis examining the impact of vocabulary instruction on vocabulary knowledge and skill. Reading Psychology, 44(6), 672–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, B., Cheung, A., & Slavin, R. E. (2016). Literacy and language outcomes of comprehensive and developmental-constructivist approaches to early childhood education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 18, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, M. (2006). Reading achievement gaps, correlates, and moderators of early reading achievement: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS) kindergarten to first grade sample. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2008). Experimental evaluation of the effects of a research-based preschool mathematics curriculum. American Educational Research Journal, 45(2), 443–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2011). Early childhood mathematics intervention. Science, 333(6045), 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copur-Gencturk, Y., & Thacker, I. (2021). A comparison of perceived and observed learning from professional development: Relationships among self-reports, direct assessments, and teacher characteristics. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(2), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, M. D., McCoach, D. B., Loftus, S., Zipoli, R., Ruby, M., Crevecoeur, Y. C., & Kapp, S. (2010). Direct and extended vocabulary instruction in kindergarten: Investigating transfer effects. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 3(2), 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, M. D., Oldham, A., Dougherty, S. M., Leonard, K., Koriakin, T., Gage, N. A., Burns, D., & Gillis, M. (2018). Evaluating the effects of supplemental reading intervention within an mtss or rti reading reform initiative using a regression discontinuity design. Exceptional Children, 84(4), 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F., & Heckman, J. (2007). The technology of skill formation. American Economic Review, 97(2), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D. K., & Caswell, L. (2007). Building support for language and early literacy in preschool classrooms through in-service professional development: Effects of the Literacy Environment Enrichment Program (LEEP). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(2), 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D. K., & Porche, M. V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading abilities. Child Development, 82(3), 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., Pagani, L., Feinstein, L., Engel, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Sexton, H., Duckworth, K., Japel, C., Cordray, D., Ginsburg, H., Grissmer, D., Lipsey, M., Raver, C., Sameroff, A., … Zill, N. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, A., Bönisch, H., Ostermöller, J., Chipperfield, M. P., Dhomse, S., & Jöckel, P. (2018). A refined method for calculating equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 18(2), 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancher, L. A., Priestley-Hopkins, D. A., & Jeffries, L. M. (2018). Handwriting acquisition and intervention: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(4), 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farver, J. A. M., Lonigan, C. J., & Eppe, S. (2009). Effective early literacy skill development for young Spanish-Speaking English language learners: An experimental study of two methods. Child Development, 80(3), 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, L., Kerr, N., & Rosier, P. (2007). Annual growth for all students: Catch up growth for those who are behind. The New Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischel, J. E., Bracken, S. S., Fuchs-Eisenberg, A., Spira, E. G., Katz, S., & Shaller, G. (2007). Evaluation of curricular approaches to enhance preschool early literacy skills. Journal of Literacy Research, 39(4), 471–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman-Krauss, A. H., & Bernett, W. S. (2023). State(s) of early intervention and early childhood special education|national institute for early education research. The National Institute for Early Education Research. Available online: https://nieer.org/research-library/states-early-intervention-early-childhood-special-education (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Gerde, H. K., Bingham, G. E., & Pendergast, M. L. (2015). Reliability and validity of the Writing Resources and Interactions in Teaching Environments (WRITE) for preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H. K., Bingham, G. E., & Wasik, B. A. (2012). Writing in early childhood classrooms: Guidance for best practices. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(6), 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H. K., Skibbe, L. E., Wright, T. S., & Douglas, S. N. (2019). Evaluation of head start curricula for standards-based writing instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(1), 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettinger, M., & Stoiber, K. (2008). Applying a response-to-intervention model for early literacy development in low-income children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 27(4), 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J. M., Lonigan, C. J., & Farver, J. A. M. (2017). Impacts of a literacy-focused preschool curriculum on the early literacy skills of language-minority children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J. W., Taylor, B. J., Olchowski, A. E., & Cumsille, P. E. (2006). Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 11(4), 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Atwater, J., Goldstein, H., Kaminski, R., & McConnell, S. (2013). Is a response to intervention (RTI) approach to preschool language and early literacy instruction needed? Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(1), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslip, M. J., & Gullo, D. F. (2018). The changing landscape of early childhood education: Implications for policy and practice. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(3), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjetland, H. N., Brinchmann, E. I., Scherer, R., Hulme, C., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2020). Preschool pathways to reading comprehension: A systematic meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review, 30, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., Cabell, S. Q., & Joyner, R. E. (2022). Effects of integrated literacy and content-area instruction on vocabulary and comprehension in the elementary years: A meta-analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(3), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, L. E. (2009). Development, interpretation, and application of the W score and the relative proficiency index. Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. M., Duncan, G. J., Auger, A., Bitler, M., Domina, T., & Burchinal, M. (2018). Boosting school readiness: Should preschool teachers target skills or the whole child? Economics of Education Review, 65, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J. M., Whitaker, A. A., Nguyen, T., & Yu, W. (2019). Distinctions without a difference? Preschool curricula and children’s development. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 12(3), 514–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y. S., Magnuson, K., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Yoshikawa, H., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2020). What works in early childhood education programs?: A meta–analysis of preschool enhancement programs. Early Education and Development, 31(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L. M., Meier, J., & Walpole, S. (2005). Learning new words from storybooks. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karch, A. (2013). Early start: Preschool politics in the United States. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, M. A. (2020). Interpreting effect sizes of education interventions. Educational Researcher, 49(4), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuddus, M. A., Tynan, E., & McBryde, E. (2020). Urbanization: A problem for the rich and the poor? Public Health Reviews, 41(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Language and Reading Research Consortium, Lo, M.-T., & Xu, M. (2022). Impacts of the let’s know! Curriculum on the language and comprehension-related skills of prekindergarten and kindergarten children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1205–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., & Rhemtulla, M. (2013). Planned Missing Data Designs for Developmental Researchers. Child Development Perspectives, 7(4), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J. A., Piasta, S. B., Purtell, K. M., Nichols, R., & Schachter, R. E. (2024). Early childhood language gains, kindergarten readiness, and Grade 3 reading achievement. Child Development, 95(2), 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, C. J. (2015). Literacy development. In Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Cognitive processes (7th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 763–805). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, C. J., Farver, J. M., Phillips, B. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2011). Promoting the development of preschool children’s emergent literacy skills: A randomized evaluation of a literacy-focused curriculum and two professional development models. Reading and Writing, 24(3), 305–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, C. J., Purpura, D. J., Wilson, S. B., Walker, P. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2013). Evaluating the components of an emergent literacy intervention for preschool children at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114(1), 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonigan, C. J., Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (2007). Test of preschool early literacy (TOPEL). PRO-ED. Available online: https://www.proedinc.com/Products/12440/topel-test-of-preschool-early-literacy.aspx (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Lonigan, C. J., & Wilson, S. B. (2008). Report on the revised Get Ready to Read! Screening tool: Psychometrics and normative information. National Center for Learning Disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, L. A., Hagen, M. P., McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., Meltzoff, A. N., & Rosen, M. L. (2021). Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status and academic achievement in early childhood: Cognitive stimulation and language. Cognitive Development, 58, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, R. (2002). Testimonies to congress. Center for the Development of Learning. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED475205.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Madsen, K. M., Peters-Sanders, L. A., Kelley, E. S., Barker, R. M., Seven, Y., Olsen, W. L., Soto-Boykin, X., & Goldstein, H. (2023). Optimizing vocabulary instruction for preschool children. Journal of Early Intervention, 45(3), 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashburn, A., Justice, L. M., McGinty, A., & Slocum, L. (2016). The impacts of a scalable intervention on the language and literacy development of rural pre-kindergartners. Applied Developmental Science, 20(1), 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, S. R., Bradfield, T. A., & Wackerle-Hollman, A. K. (2014). Early childhood literacy screening. In Universal screening in educational settings: Evidence-based decision making for schools (pp. 141–170). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, A. S., & Justice, L. M. (2009). Predictors of print knowledge in children with specific language impairment: Experiential and developmental factors. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(1), 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, K., Dailey, D., & Shcrank, F. (2007). Woodcock-Johnson III/Woodcock-Johnson III normative update score differences: What the user can expect and why (Woodcock-Johnson III assessment service bulletin No. 9). Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, A., Butera, G., & Friesen, A. (2017). Examining the use of curriculum to support early literacy instruction: A multiple case study of head start teachers. Early Education and Development, 28(3), 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnane, R. J., & Duncan, G. J. (2011). Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. Russell Sage Foundation. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/207/monograph/book/26993 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2017). Mplus (Version 8) [Computer software]. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Myrtil, M. J., Justice, L. M., & Jiang, H. (2019). Home-literacy environment of low-income rural families: Association with child- and caregiver-level characteristics. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). A new vision for high-quality preschool curriculum. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education & Board on Children, Youth, and Families. (2023). Closing the opportunity gap for young children [Consensus Study Report]. National Academies Press (US). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2022). The power of playful learning. Available online: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/summer2022/power-playful-learning (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). Students with disabilities. Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- National Early Literacy Panel. (2008). Developing early literacy. National Institute for Literacy. Available online: https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Neuman, S. B. (2006). The knowledge gap: Implications for early education. In D. K. Dickinson, & S. B. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 29–40). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S. B., & Dwyer, J. (2009). Missing in action: Vocabulary instruction in Pre-K. The Reading Teacher, 62(5), 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (2005). The state of state pre-kindergarten standards. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20(2), 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, S. B., & Snow, C. (2000). Instructional material: Building language for literacy (Research-based early literacy instruction). Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T., Duncan, G. J., & Jenkins, J. M. (2018). Boosting school readiness with preschool curricula. In Sustaining early childhood learning gains (pp. 74–100). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J. Z. (2003). Handwriting without tears: Teacher’s guide (9th ed.). Handwriting Without Tears. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, T. C., Spanoudis, G., Ktisti, C., & Fella, A. (2021). Precocious readers: A cognitive or a linguistic advantage? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfost, M., Hattie, J., Dörfler, T., & Artelt, C. (2014). Individual differences in reading development: A review of 25 years of empirical research on matthew effects in reading. Review of Educational Research, 84(2), 203–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B. (2016). Current understandings of what works to support the development of emergent literacy in early childhood classrooms. Child Development Perspectives, 10(4), 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Hudson, A., Sayers, R., Logan, J. A. R., Lewis, K., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., & Bailet, L. L. (2024). Small-Group Emergent Literacy Intervention Dosage in Preschool: Patterns and Predictors. Journal of Early Intervention, 46(1), 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Thomas, L. J. G., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., Bailet, L. L., & Lewis, K. (2021). Implementation of a small-group emergent literacy intervention by preschool teachers and community aides. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 54, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., Bailet, L. L., Lewis, K., & Thomas, L. J. G. (2023). Small-group, emergent literacy intervention under two implementation models: Intent-to-treat and dosage effects for preschoolers at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 56(3), 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasta, S. B., Phillips, B. M., Williams, J. M., Bowles, R. P., & Anthony, J. L. (2016). Measuring young children’s alphabet knowledge: Development and validation of brief letter-sound knowledge assessments. Elementary School Journal, 116(4), 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasta, S. B., Shea, Z., Hudson, A. K., Shen, Y., Logan, J. A., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., & Lewis, K. (2025). Initial Skills Predict Preschoolers’ Emergent Literacy Development but Do Not Moderate Response to Intervention. Infant and Child Development, 34(3), e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research Consortium. (2008). Effects of preschool curriculum programs on school readiness (NCER 2008–2009). National Center for Education Research. Institute of Education Sciences. U.S. Department of Education. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Puranik, C. S., & Lonigan, C. J. (2014). Emergent writing in preschoolers: Preliminary evidence for a theoretical framework. Reading Research Quarterly, 49(4), 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A. J., Ou, S.-R., Mondi, C. F., & Hayakawa, M. (2017). Processes of early childhood interventions to adult well-being. Child Development, 88(2), 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhemtulla, M., & Hancock, G. R. (2016). Planned missing data designs in educational psychology research. Educational Psychologist, 51(3–4), 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S., & Willer, B. (2008). Curriculum: A guide to the NAEYC early childhood program standard and related accreditation criteria. National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). [Google Scholar]

- Sabol, T. J., Ross, E. C., & Frost, A. (2020). Are all head start classrooms created equal? Variation in classroom quality within head start centers and implications for accountability systems. American Educational Research Journal, 57(2), 504–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A. J., & Chandler, M. J. (1975). Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. Review of Child Development Research, 4(1), 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, K. M. P. (2023). Can early childhood education be compensatory? Examining the benefits of child care among children who experience neglect. Early Education and Development, 34(6), 1398–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, R., Piasta, S. B., & Logan, J. A. R. (2020). Implementing a small-group literacy program in preschool classrooms: Impacts of the Nemours BrightStart! Program [Study Protocol Preregistration]. Open Science Framework. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, R., Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., Bailet, L. L., & Lewis, K. (2021). Identifying and helping preschoolers in Columbus needing extra literacy support [White paper]. Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy. Available online: https://crane.osu.edu/our-work/identifying-and-helping-preschoolers-in-columbus-who-may-benefit-from-extra-literacy-support (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Schachter, R. E., Piasta, S., & Justice, L. (2020). An investigation into the curricula (and quality) used by early childhood educators. HS Dialog: The Research to Practice Journal for the Early Childhood Field, 23(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinhart, L., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., Barnett, S., Belfield, C., & Nores, M. (2005). The high/scope perry preschool study through age 40 summary, conclusions, and frequently asked questions (pp. 194–215). High/Scope® Educational Research Foundation. Available online: www.highscope.org (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Shea, Z. M., & Jenkins, J. M. (2021). Examining heterogeneity in the impacts of socio-emotional curricula in preschool: A quantile treatment effect approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 624320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibbe, L. E., Gerde, H. K., Wright, T. S., & Samples-Steele, C. R. (2016). A content analysis of phonological awareness and phonics in commonly used head start curricula. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(3), 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. E., & Matthews, T. J. (2016). Reading and language in the early grades. The Future of Children, 26(2), 57–74. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43940581 (accessed on 18 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata statistical software: Release 17 [Computer software]. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber, K. C., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Multi-tiered systems of support and evidence-based practices. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention (pp. 121–141). Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaching Strategies, Inc. (2018). The critical role of instructional strategies in promoting early literacy. Available online: https://teachingstrategies.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/TSI_Research-Paper_Literacy.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Tortorelli, L. S., Bowles, R. P., & Skibbe, L. E. (2017). Easy as AcHGzrjq: The quick letter name knowledge assessment. The Reading Teacher, 71(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toub, T. S., Hassinger-Das, B., Nesbitt, K. T., Ilgaz, H., Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Nicolopoulou, A., & Dickinson, D. K. (2018). The language of play: Developing preschool vocabulary through play following shared book-reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 45(4), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, K., Nord, C., Lê, T., Sorongon, A. G., & Najarian, M. (2009). Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K): Combined User’s Manual for the ECLS-K Eighth-Grade and K-8 Full Sample Data Files and Electronic Codebooks (NCES 2009-004). National Center for Education Statistics.

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. (2010). WWC intervention report: Literacy express. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/WWC/Docs/InterventionReports/wwc_lit_express_072710.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. (2013). The creative curriculum® for preschool. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/InterventionReports/wwc_creativecurriculum_081109.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Vaughn, S., & Fletcher, J. M. (2021). Identifying and teaching students with significant reading problems. American Educator, 44(4), 4–11, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Wackerle-Hollman, A. K., Rodriguez, M. I., Bradfield, T. A., Rodriguez, M. C., & McConnell, S. R. (2015). Development of early measures of comprehension: Innovation in individual growth and development indicators. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 40(2), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. A., & Petty, K. (2007). Frequency of six early childhood education approaches: A 10-year content analysis of early childhood education journal. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(5), 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. H., Firmender, J. M., Power, J. R., & Byrnes, J. P. (2016). Understanding the Program Effectiveness of Early Mathematics Interventions for Prekindergarten and Kindergarten Environments: A Meta-Analytic Review. Early Education and Development, 27(5), 692–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, T. W., Jenkins, J. M., Dodge, K. A., Carr, R. C., Sauval, M., Bai, Y., Escueta, M., Duer, J., Ladd, H., Muschkin, C., Peisner-Feinberg, E., & Ananat, E. (2023). Understanding heterogeneity in the impact of public preschool programs. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 88(1), 7–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, C., McCormick, M., Mattera, S., Maier, M., & Morris, P. (2018). Preschool curricula and professional development features for getting to high-quality implementation at scale: A comparative review across five trials. AERA Open, 4(1), 2332858418757735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69(3), 848–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (2010). Get read to read!—Revised edition. Pearson Assessments. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, M. J., Gray, S. I., Guimond, A. B., & Lafferty, A. E. (2011). Efficacy of the TELL language and literacy curriculum for preschoolers with developmental speech and/or language impairment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(3), 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. B., & Lonigan, C. J. (2010). Identifying preschool children at risk of later reading difficulties: Evaluation of two emergent literacy screening tools. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(1), 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., Hubbard, R. A., & Himes, B. E. (2020). Neighborhood-level measures of socioeconomic status are more correlated with individual-level measures in urban areas compared to less urban areas. Annals of Epidemiology, 43, 37–43.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., & Logan, J. A. R. (2021). Treatment effects in longitudinal two-method measurement planned missingness designs: An application and tutorial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 14(2), 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H., Weiland, C., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2016). When does preschool matter? Future of Children, 26(2), 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, H., Weiland, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., Burchinal, M., Espinosa, L. M., Gormley, W. T., Jens, L., Magnuson, K. A., Phillips, D., & Zaslow, M. J. (2013). Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education. Foundation for Child Development. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, F., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2013). Head start, prekindergarten, and academic school readiness: A comparison among regions in the united states. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(3), 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teacher-Reported Curriculum | Literacy-Focused | Non-Literacy-Focused |

|---|---|---|

| Handwriting Without Tears | 8 | |

| Building Language for Literacy | 7 | |

| Opening the World of Learning (OWL) | 5 | |

| The Emerging Language and Literacy Curriculum | 4 | |

| Language for Learning | 4 | |

| Letter People | 3 | |

| Nemours BrightStart! | 3 | |

| Read, Play, and Learn! | 3 | |

| Ready, Set, Leap | 3 | |

| Innovations | 2 | |

| Read it Again! PreK | 2 | |

| Dynamic Learning Maps® (DLM) Early Childhood Express | 1 | |

| Curiosity Corner | 1 | |

| Imagine it! | 1 | |

| McGraw Hill | 1 | |

| Reading Street | 1 | |

| Storytown | 1 | |

| Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System | 13 | |

| Creative Curriculum/Teaching Strategies Gold | 76 | |

| Everyday Mathematics | 7 | |

| High Scope | 1 | |

| Reggio Emilia Approach | 11 | |

| Scholastic | 10 | |

| The Core Knowledge Preschool Sequence | 4 | |

| Other | 10 | |

| Total number of classrooms in which curriculum was used | 15 | 83 |

| Total number of teachers reporting use of the curriculum | 50 | 132 |

| Observed Variable. | Print and Letter Knowledge | ||||

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Print knowledge | Overall sample (N = 571) | 8.50 | 8.41 | 17.28 | 10.74 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 8.85 | 9.17 | 20.90 | 10.69 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 8.48 | 8.34 | 16.85 | 10.67 | |

| Letter-name knowledge | Overall sample (N = 571) | 15.56 | 16.46 | 25.56 | 17.05 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 17.95 | 18.29 | 29.90 | 16.38 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 15.15 | 16.05 | 24.96 | 17.07 | |

| Letter-sound knowledge | Overall sample (N = 571) | 5.18 | 6.62 | 9.54 | 8.06 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 6.06 | 7.30 | 12.26 | 8.59 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 5.06 | 6.51 | 9.21 | 7.87 | |

| Observed Variable | Phonological awareness | ||||

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Phonological awareness | Overall sample (N = 571) | 9.70 | 4.92 | 12.80 | 5.15 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 9.85 | 4.36 | 13.56 | 4.82 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 9.78 | 5.02 | 12.68 | 5.23 | |

| Rhyme awareness | Overall sample (N = 571) | 3.18 | 4.16 | 5.89 | 5.41 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 2.52 | 3.84 | 5.24 | 5.44 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 3.34 | 4.22 | 6.05 | 5.43 | |

| Initial sound awareness | Overall sample (N = 571) | 6.67 | 3.61 | 8.48 | 3.74 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 6.45 | 3.70 | 9.04 | 3.39 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 6.75 | 3.60 | 8.41 | 3.81 | |

| Observed Variable | Language and comprehension | ||||

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Narrative language | Overall sample (N = 571) | 18.57 | 2.03 | 19.71 | 1.79 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 18.91 | 2.11 | 19.92 | 1.54 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 18.55 | 2.00 | 19.66 | 1.84 | |

| Listening comprehension | Overall sample (N = 571) | 439.61 | 15.26 | 448.59 | 16.13 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 441.85 | 15.79 | 450.67 | 17.01 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 439.44 | 15.18 | 448.52 | 16.04 | |

| Vocabulary | Overall sample (N = 571) | 5.00 | 3.02 | 7.10 | 3.15 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 4.61 | 3.04 | 7.09 | 3.34 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 5.09 | 3.02 | 7.12 | 3.14 | |

| Observed Variable | Emergent writing | ||||

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Name writing | Overall sample (N = 571) | 2.05 | 1.08 | 2.93 | 0.96 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 2.20 | 1.18 | 3.23 | 0.88 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 2.05 | 1.06 | 2.91 | 0.96 | |

| Letter writing | Overall sample (N = 571) | 1.66 | 0.85 | 2.41 | 1.00 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 1.77 | 0.90 | 2.65 | 0.98 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 1.66 | 0.85 | 2.39 | 1.00 | |

| Invented spelling | Overall sample (N = 571) | 1.24 | 0.53 | 1.65 | 0.82 |

| Literacy-focused curricula (n = 80) | 1.32 | 0.65 | 1.84 | 0.93 | |

| Non-literacy-focused curricula (n = 479) | 1.23 | 0.51 | 1.63 | 0.81 | |

| Full Sample (Child N = 571) | Emergent Literacy-Focused (Child n = 80) | Non-Emergent Literacy-Focused (Child n = 479) | ||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Children at risk of later reading difficulties | 280 | 49.21 | 39 | 48.75 | 236 | 49.27 |

| Received intervention | 394 | 69.18 | 44 | 55.00 | 340 | 71.19 |

| Head Start | 251 | 44.49 | 12 | 15.38 | 235 | 48.76 |

| Public school | 508 | 89.15 | 58 | 72.5 | 441 | 91.97 |

| Programs accepting subsidies | 383 | 66.67 | 35 | 43.75 | 340 | 70.79 |

| Urban | 126 | 21.52 | 18 | 22.5 | 101 | 21.35 |

| Variable | β | SE | p |

| Print and letter knowledge | |||

| Literacy-focused curricula | 0.217 | 0.132 | 0.10 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | −0.067 | 0.031 | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.157 | 0.036 | <0.01 |

| Child had an Individualized Education Program or 504 plan | −0.047 | 0.031 | 0.13 |

| Parents’ highest degree | 0.024 | 0.033 | 0.47 |

| Get Ready to Read-Revised | 0.024 | 0.054 | 0.66 |

| Latent print and letter pretest | 0.759 a | 0.048 | <0.01 |

| Phonological awareness | |||

| Literacy-focused curricula | 0.774 | 0.302 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.030 | 0.059 | 0.61 |

| Annual household income | 0.076 | 0.035 | 0.03 |

| Get Ready to Read-Revised | −0.031 | 0.100 | 0.76 |

| Latent phonological awareness pretest | 0.971 a | 0.122 | <0.01 |

| Language and comprehension | |||

| Literacy-focused curricula | 0.148 | 0.162 | 0.36 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | −0.037 | 0.030 | 0.22 |

| Race | −0.062 | 0.030 | 0.04 |

| Age | −0.015 | 0.042 | 0.72 |

| Annual household income | −0.055 | 0.037 | 0.14 |

| Get Ready to Read-Revised | 0.025 | 0.050 | 0.61 |

| Latent language and comprehension pretest | 1.002 a | 0.059 | <0.01 |

| Emergent writing | |||

| Emergent literacy-focused curricula | 0.198 | −0.135 | 0.14 |

| Age | 0.172 | 0.043 | <0.01 |

| Girl | 0.103 | 0.031 | <0.01 |

| Parents’ highest degree | 0.047 | 0.034 | 0.17 |

| Child had an Individualized Education Program or 504 plan | 0.021 | 0.033 | 0.52 |

| Get Ready to Read-Revised | 0.166 | 0.045 | <0.01 |

| Latent emergent writing pretest | 0.638 a | 0.054 | <0.01 |

| Risk Status | Intervention | Public | Head Start | Subsidy | Urban | |||||||||||||

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Print & letter knowledge | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy-focused curricula | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Moderator | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.41 | −0.15 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.81 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Curricula X Moderator | 0.12 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.93 |

| Phonological awareness | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy-focused curricula | −0.33 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| Moderator | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.59 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.46 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Curricula X Moderator | 0.10 | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.81 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.77 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.42 |

| Language & comprehension | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy-focused curricula | −0.16 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.85 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.29 |

| Moderator | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.26 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.83 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.66 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.50 |

| Curricula X Moderator | 0.11 | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.49 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| Emergent writing | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy-focused curricula | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.28 |

| Moderator | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.70 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.59 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Curricula X Moderator | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.58 |

| Print and Letter Knowledge | Phonological Awareness | Language and Comprehension | ||||

| Group Comparisons | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Literacy-curricula-at risk vs. Non-literacy-curricula-at risk | 0.110 | <0.001 | 0.080 | 0.016 | 0.096 | 0.004 |

| Literacy-curricula-at risk vs. Non-literacy-curricula-not at risk | 0.096 | 0.016 | −0.029 | 0.510 | 0.059 | 0.142 |

| Literacy-curricula-not at risk vs. Non-literacy-curricula-not at risk | −0.006 | 0.862 | 0.016 | 0.673 | −0.044 | 0.185 |

| Non-literacy-curricula-not at risk vs. Non-literacy- curricula-at risk | 0.036 | 0.323 | 0.166 | <0.001 | 0.151 | <0.001 |

| Literacy-curricula-at risk vs. Non-literacy-curricula-not at risk | 0.091 | 0.003 | −0.012 | 0.736 | 0.016 | 0.626 |

| Literacy-curricula-not at risk vs. Non-literacy-curricula-at risk | 0.014 | 0.693 | 0.105 | 0.006 | 0.037 | 0.260 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shea, Z.M.; Piasta, S.B.; Shen, Y.; Hudson, A.K.; Zettler-Greeley, C.M.; Lewis, K.; Logan, J.A.R. Is Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula Associated with Children’s Literacy Gains and Are Associations Moderated by Risk Status, Receipt of Intervention, or Preschool Setting? Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101368

Shea ZM, Piasta SB, Shen Y, Hudson AK, Zettler-Greeley CM, Lewis K, Logan JAR. Is Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula Associated with Children’s Literacy Gains and Are Associations Moderated by Risk Status, Receipt of Intervention, or Preschool Setting? Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101368

Chicago/Turabian StyleShea, Zhiling Meng, Shayne B. Piasta, Ye Shen, Alida K. Hudson, Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, Kandia Lewis, and Jessica A. R. Logan. 2025. "Is Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula Associated with Children’s Literacy Gains and Are Associations Moderated by Risk Status, Receipt of Intervention, or Preschool Setting?" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101368

APA StyleShea, Z. M., Piasta, S. B., Shen, Y., Hudson, A. K., Zettler-Greeley, C. M., Lewis, K., & Logan, J. A. R. (2025). Is Use of Literacy-Focused Curricula Associated with Children’s Literacy Gains and Are Associations Moderated by Risk Status, Receipt of Intervention, or Preschool Setting? Education Sciences, 15(10), 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101368