Exploring the Power and Possibility of Contextually Relevant Social Studies–Literacy Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Grounding

2.1. The Active View of Reading

2.2. Contextually Relevant Pedagogy

2.2.1. Academic Achievement

2.2.2. Origination Conception

2.2.3. Place-Based Understanding

3. Research on Knowledge Activation and Knowledge Building

3.1. Knowledge Activation

3.2. Knowledge Building

4. Current Study

- (1)

- What are the effects of an integrated, context-specific unit on students’ breadth of conceptually related vocabulary words, as compared to students in a control group?

- (2)

- What are the effects of an integrated, context-specific unit on students’ reading and social studies interest, as compared to students in a control group?

- (3)

- What connections to deeper understandings and multiple perspectives do students demonstrate through informal, end-of-unit retellings?

5. Methods

5.1. Partnership Context and Participants

5.2. Study Design

5.2.1. Professional Learning

5.2.2. Social Studies and Literacy Integration

5.3. Texts

5.4. Word Knowledge and Vocabulary

5.5. Knowledge Activation, Integration, and Revision

6. Unit Implementation and Fidelity

7. Data Sources

7.1. Vocabulary Recognition Task

7.2. Reading and Social Studies Interest

7.3. Student Retellings

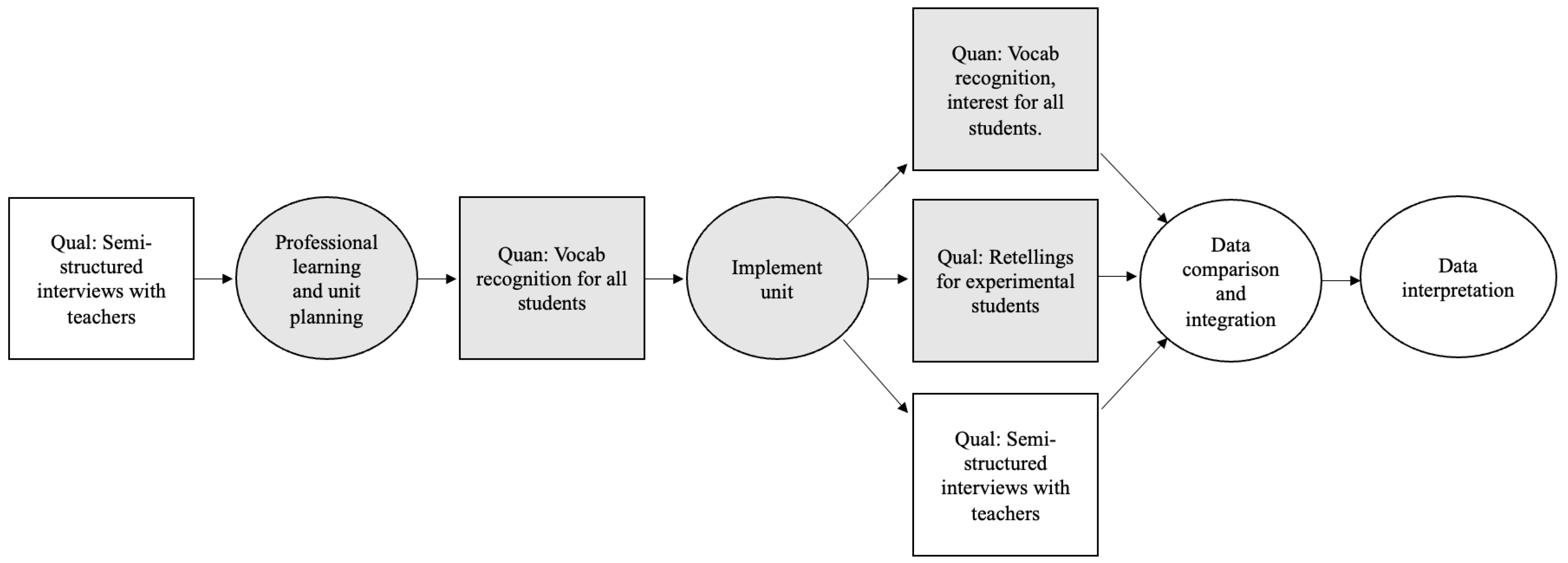

7.4. Mixed Methods Approach

8. Results

8.1. Quantitative

8.2. Qualitative

We have garbage cans, we bring those down, dump it in the trash. … Well, you gotta take out your trash or you’re going to end up with it being a million feet tall, and it falls and you can’t take out your trash and your house will be a whole dump. You also have to commit and do stuff that helps the community.

We learned that in Japan, people usually eat with chopsticks, but usually how we eat, we eat with forks, spoons, knives, and stuff. And we drive different. Some people use horses to get to school, some people walk, some people drive, and some people ride a bike.

9. Discussion

9.1. Connections to Theoretical Perspectives

9.2. Limitations and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Outline of Professional Learning Sessions

| Session Focus | Outcomes |

| Unit planning: Infusing social studies content with reading standards and developing relevant tasks. |

|

| Contextually relevant text selection: Selecting conceptually related texts that provide access to multiple perspectives. |

|

| Vocabulary instruction: Grounding instruction in evidence-based practices. |

|

| Knowledge development: Instructional techniques to build connections to and disconnections from content. |

|

| Finalizing the plan |

|

Appendix B. Texts and Vocabulary Words

- Sarah Cynthia Stout Would Not Take the Garbage Out

- Roxaboxen

- On the Town

- Look Where We Live

- Last Stop on Market Street

- City or Country

- Kids Academy Video

- Subway Ride

- A City

- Farming

- Farmers

- Whose Hands Are These?

- Whose Tools are These?

- Look Where We Live

- Maybe Something Beautiful

- Diego Rivera: His World and Ours

- Murals: Walls that Sing

- Me on the Map

- Be My Neighbor

- This is My House

- My House

- Quinito’s Neighborhood

- On the Town

- A Chair for My Mother

- Same Same But Different

- This is How We Do It

- My Food, Your Food, Our Food

- Community Soup

- Mama Panya’s Pancakes

- Where Are You From?

Appendix C. Fidelity Rubric

| Ineffective (1) | Developing (2) | Skilled (3) | Accomplished (4) |

| There is no evidence of this practice. Additional professional learning is needed. | The teacher attempts to incorporate this practice, but misses the mark. Additional professional learning is needed. | The teacher is fairly competent in incorporating this practice into their classroom instruction. | The teacher goes above and beyond to seamlessly incorporate this practice into classroom instruction. |

| Integrating social studies knowledge and reading strategies. | ||

| Incorporates social studies content into the lesson. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Incorporates comprehension reading strategies into the lesson. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Text and vocabulary selection. | ||

| Includes text(s) related to the focal content. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Texts are contextually relevant and provide access to historically minoritized perspectives | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Includes target vocabulary words related to the focal content. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Evidence-based vocabulary instructional techniques. | ||

| Provides student-friendly definitions of target words. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Introduces target words in context. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Provides multiple opportunities to read, write, or talk about target words. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Making connections and disconnections to content and vocabulary knowledge. | ||

| Provides opportunities for students to make connections to the content. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

| Provides opportunities for students to make disconnections from the content. | ● Ineffective ● Developing ● Skilled ● Accomplished | Evidence: |

Appendix D. Vocabulary Recognition Task Pre-Assessment

| Suburb | Magnet | Occupation |

| Unity | Hairpin | Urban |

| Turtle | Blanket | Participate |

| Rural | Responsibility | Glasses |

| Global | Culture | Contribute |

| Town | Planets | Village |

| Government | City | Cooperation |

| Farm | Puzzle | Neighborhood |

Appendix E. Reading and Social Studies Interest

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

|  |  |  |  |

| Not at all | A little bit | Somewhat | Pretty much | A lot |

Appendix F. Community Unit Retelling

- Print vocabulary words (community, local, global, contribute, responsible)

- Have 2 to 3 local texts and 2 to 3 global texts out for students to reference.

- (1)

- Show student the word community. Read the word.

- ▪

- You have been learning and reading texts about community. What did you learn about communities?

- ▪

- What did you learn about rural communities?

- ▪

- suburban

- ▪

- urban

- (2)

- Show student the word local. Read the word.

- ▪

- Here are two books that you read (read the titles). What did you learn from reading about local communities? What do you remember about these books? Allow student to open the books and look through them.

- ▪

- You have been learning about your local community here in Bluestem. What did you learn about Bluestem?

- ▪

- Follow-up questions below. Italicized questions are less of a priority given time and student stamina.

- ▪

- How do people contribute to Bluestem? (show word)

- ▪

- How are community members in Bluestem responsible to each other? (show word)

- ▪

- What did you learn about community leaders?

- ▪

- Who are some community leaders in Bluestem?

- ▪

- What did you learn about community members?

- ▪

- How can you participate in your community?

- (3)

- Show student the word global. Read the word.

- ▪

- Here are two books that you read (read the titles). What did you learn from reading about global communities around the world? What do you remember about these books? Allow student to open the books and look through them.

- ▪

- You have been learning about global communities. What did you learn about these communities?

- ▪

- Follow-up questions below.

- ▪

- How do people contribute to communities around the world? Option to prompt for similarities/differences compared to Bluestem.

- ▪

- How are communities members around the world responsible to each other?

References

- Afflerbach, P., Pearson, P. D., & Paris, S. G. (2008). Clarifying differences between reading skills and reading strategies. The Reading Teacher, 61(5), 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P. A. (2005). The path to competence: A lifespan developmental perspective on reading. Journal of Literacy Research, 37, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azano, A. P. (2011). The possibility of place: One teacher’s use of place-based instruction for English students in a rural high school. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 26(10), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Azano, A. P., Brenner, D., Downey, J., Eppley, K., & Schulte, A. K. (2020). Teaching in rural places. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Azano, A. P., & Stewart, T. T. (2015). Exploring place and practicing justice: Preparing preservice teachers for success in rural schools. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 30(9), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. S., Peleg-Bruckner, Z., & McClintock, A. H. (1985). Effects of topic interest and prior knowledge on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 20(4), 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballenger, C. (2004). Reading storybooks with young children: The case of The Three Robbers. In C. Ballenger (Ed.), Regarding children’s words: Teacher research on language and literacy (pp. 31–42). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai, S., Zohar, A. R., & Mor-Hagani, S. (2018). Promoting integration of multiple texts: A review of instructional approaches and practices. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 973–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, W., & Moorman, G. (1990). The presentation of reading lessons. Reading Research and Instruction, 29(3), 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M. K., Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2023). Evaluating components of the active view of reading as intervention targets: Implications for social justice. School Psychology, 38(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabell, S. Q., & Hwang, H. (2020). Building content knowledge to boost comprehension in the primary grades. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(Suppl. S1), S99–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetti, G. N., Wright, T. S., & Hwang, H. (2016). Conceptual coherence, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition: A knowledge effect? Reading and Writing, 29, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., & Schutz, P. A. (2017). Developing a mixed methods proposal: A practical guide for beginning researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- de la Peña, M. (2015). Last stop on market street. Putnam Sons Books for Young Readers. [Google Scholar]

- Dole, J. A., Duffy, G. G., Roehler, L. R., & Pearson, P. D. (1991). Moving from the old to the new: Research on reading comprehension instruction. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotwals, A. W., & Wright, T. (2017). From “Plants don’t eat” to “Plants are producers”: The role of vocabulary in scientific sense-making. Science and Children, 55(3), 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., David, M. H., Scafiddi, N. T., & Tonks, S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(3), 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C. (2024). Supporting students’ knowledge activation before, during, and after reading. The Reading Teacher, 77(6), 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., & Alexander, P. A. (2021). The effects of knowledge activation training on rural middle school students’ expository text comprehension: A mixed methods study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(5), 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., Alexander, P. A., & Lupo, S. M. (2024). Leveraging what students know to make sense of texts: What the research says about prior knowledge activation. Review of Educational Research, 94(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., & Dinsmore, D. L. (2019). Examining elementary students’ purposeful and ancillary prior knowledge activation when reading grade level texts. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 58(2), 24–47. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol58/iss2/3 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Hattan, C., & Kendeou, P. (2024). Expanding the science of reading: Contributions from educational psychology. Educational Psychologist, 59(4), 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., Lee, E., & List, A. (2023). Comprehension, diagram analysis, integration, and interest: A cross-sectional analysis. Reading Psychology, 44(7), 731–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., & Lupo, S. M. (2020). Rethinking the role of knowledge in the literacy classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattan, C., MacPhee, D., & Zuiderveen, C. (2025). Vocabulary instruction during elementary classroom discourse: Observing 1st through 3rd grade teachers’ instructional practices. Literacy Research and Instruction. Online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., Cabell, S. Q., & Joyner, R. E. (2021). Effects of integrated literacy and content-area instruction on vocabulary and comprehension in the elementary years: A meta-analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(3), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., Cabell, S. Q., & Joyner, R. E. (2023). Does cultivating content knowledge during literacy instruction support vocabulary and comprehension in the elementary school years? A systematic review. Reading Psychology, 44(2), 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., McMaster, K., & Kendeou, P. (2022). A longitudinal investigation of directional relations between domain knowledge and reading in the elementary years. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(1), 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, P., & Pearson, P. D. (1982, June). Prior knowledge, connectivity, and the assessment of reading comprehension (Tech. Rep. No. 245). University of Illinois, Center for the Study of Reading. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K., & Maxwell, S. E. (2019). Multiple regression. In G. R. Hancock, L. M. Stapleton, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (2nd ed., pp. 313–330). Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Kendeou, P., Butterfuss, T., Van Boekel, M., & O’Brien, E. J. (2017). Integrating relational reasoning and knowledge revision during reading. Educational Psychology Review, 29, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S., Burkhauser, M. A., Mesite, L. M., Asher, C. A., Relyea, J. E., Fitzgerald, J., & Elmore, J. (2021). Improving reading comprehension, science domain knowledge, and reading engagement through a first-grade content literacy intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S., Burkhauser, M. A., Relyea, J. E., Gilbert, J. B., Scherer, E., Fitzgerald, J., Mosher, D., & McIntyre, J. (2023). A longitudinal randomized trial of a sustained content literacy intervention from first to second grade: Transfer effects on students’ reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(1), 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge Matters Campaign. (2022). Statement from the knowledge matters campaign scientific advisory committee. Available online: https://knowledgematterscampaign.org/statement-from-the-knowledge-matters-campaign-scientific-advisory-committee/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Kostecki-Shaw, J. S. (2011). Same, same but different. Square Fish. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Racialized discourses and ethnic epistemologies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 257–277). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: Aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G., & Dixson, A. (2021). Put some respect on the theory: Confronting distortions of culturally relevant pedagogy. In C. Compton-Lilly, T. L. Ellison, K. Perry, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Whitewashed cultural perspectives: Restoring the edge to edgy ideas (pp. 122–137). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lapp, D., Grant, M., Moss, B., & Johnson, K. (2013). Students’ close reading of science texts: What’s now? What’s next? The Reading Teacher, 67(2), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lupo, S. M., Berry, A., Thacker, E., Sawyer, A., & Merritt, J. (2020). Rethinking text sets to support knowledge building and interdisciplinary learning. The Reading Teacher, 74(4), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, S. M., Hardigree, C., Thacker, E., Sawyer, A., & Merritt, J. (2021). Teaching disciplinary literacy in grades K-6. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lupo, S. M., Tortorelli, L., Invernizzi, M., Ryoo, J. H., & Strong, J. Z. (2019). An exploration of text difficulty and knowledge support on adolescents’ comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(4), 457–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (1998). Person-context interaction theories. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (Vol. 1, pp. 685–759). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson, T. G. (2019, March 28). How gaps in content knowledge hold students back. The Hechinger Report. Available online: https://hechingerreport.org/how-gaps-in-content-knowledge-hold-students-back/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S. B. (2019). Comprehension in disguise: The role of knowledge in children’s learning. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 45(4), 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Public School Review. (2021). Available online: https://www.publicschoolreview.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- RAND Reading Study Group (Snow, C., Chair) [RAND]. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. MR-1465-OERI. RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. (2025). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. RStudio, PBC. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Stahl, K. A. D., & Bravo, M. (2010). Contemporary classroom vocabulary assessment for content areas. The Reading Teacher, 63, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K. A. D., Flanigan, K., & McKenna, M. C. (2020). Assessment for reading instruction (4th ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Prairie School District. (n.d.). Elementary English language arts. Available online: https://www.sunprairieschools.org/academics/act-20-implementation (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Swanson, E., Vaughn, S., & Wexler, J. (2017). Enhancing adolescents’ comprehension of text by building vocabulary knowledge. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50(2), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonatiuh, D. (2011). Diego Rivera: His world and ours. Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek, J. (2014). Building word knowledge: Opportunities for direct vocabulary instruction in general education for students with reading difficulties. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 30(2), 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, J., Kearns, D., & Lemons, C. (2017). PD B [PowerPoint slides]. Project CALI content area literacy instruction. Available online: https://projectcali.uconn.edu/materials/cali-materials/pd-session-b/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Wright, T. S. (2021). A teacher’s guide to vocabulary development across the day. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T. S., Cervetti, G. N., Wise, C., & McClung, N. A. (2022). The impact of knowledge-building through conceptually-coherent read alouds on vocabulary and comprehension. Reading Psychology, 43(1), 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. S., & Neuman, S. B. (2014). Paucity and disparity in kindergarten oral vocabulary instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 46(3), 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Barger, M. M., Oh, D., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2022). Parents’ daily involvement in children’s math homework and activities during early elementary school. Child Development, 93(5), 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| * Principle | Application in Current Study |

|---|---|

| Before, during and after reading | Teachers asked purposeful questions before, during, and after reading to support students in making connections to their knowledge, experiences, and previously read texts. |

| Collaborative activation | Students shared their knowledge through whole-group conversations and turn and talks. |

| Conceptual connections | At the end of each lesson, students and teachers co-constructed a concept map using explicitly taught vocabulary words. |

| Recognize discrepancies | Teachers prompted students to consider how the text content might be different from their own knowledge and experiences. |

| Address misunderstandings | Teachers were encouraged to address misunderstandings in the moment, rather than wait to address them later in the lesson. |

| Consider topic-specific knowledge | During planning, teachers considered their students’ prior knowledge about the to-be-learned topics and scaffolded accordingly. |

| Predictor | b | b 95% CI [LL, UL] | beta | beta 95% CI [LL, UL] | SE | Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.88 ** | [3.85, 7.91] | 1.02 | |||

| Assignment | 3.62 ** | [2.21, 5.04] | 0.47 | [0.29, 0.65] | 0.71 | |

| VRT_pre | 0.37 ** | [0.16, 0.58] | 0.32 | [0.13, 0.50] | 0.11 | |

| R2 = 0.268 ** | ||||||

| 95% CI [0.11, 0.40] |

| Predictor | b | beta | SE | Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.50 ** | 0.46 | ||

| Assignment | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.32 | |

| VRT_pre | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.05 | |

| R2 = 0.00 |

| Predictor | b | beta | SE | Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.22 ** | 0.42 | ||

| Assignment | 0.78 ** | 0.03 | 0.29 | |

| VRT_pre | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| R2 = 0.08 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hattan, C.; Baumann, J.; Parkinson, M.M.; MacPhee, D. Exploring the Power and Possibility of Contextually Relevant Social Studies–Literacy Integration. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101401

Hattan C, Baumann J, Parkinson MM, MacPhee D. Exploring the Power and Possibility of Contextually Relevant Social Studies–Literacy Integration. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101401

Chicago/Turabian StyleHattan, Courtney, Jennie Baumann, Meghan M. Parkinson, and Deborah MacPhee. 2025. "Exploring the Power and Possibility of Contextually Relevant Social Studies–Literacy Integration" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101401

APA StyleHattan, C., Baumann, J., Parkinson, M. M., & MacPhee, D. (2025). Exploring the Power and Possibility of Contextually Relevant Social Studies–Literacy Integration. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101401