Continuity and Quality in Pre-Service Teacher Preparation Across Modalities: Core Principles in a Crisis Leadership Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges Confronting Pre-Service Teacher Education Programmes

2.2. Strategic Approaches to Strengthening Pre-Service Programmes

- Active, application-oriented coursework integrates inquiry projects, micro-teaching, and simulation tasks to promote deep engagement and professional readiness (Resch & Schrittesser, 2021; Sumantri et al., 2018).

- Authentic field immersion provides extended placements with observation–co-teaching cycles that expose PSTs to complex classroom dynamics and real-time decision-making (Drexhage et al., 2016; Ingersoll & Strong, 2011).

- Structured reflection employs guided journals, video-based self-analysis, and critical incident discussions to build cognitive flexibility and adaptive expertise (Flores et al., 2014; Sanchez-Caballe et al., 2020).

- Peer communities of practice use cohort seminars, online forums, and collaborative lesson study to supply mutual support and shared problem-solving (Kimmelmann & Lang, 2019; Valtonen et al., 2017).

- Expert mentoring features ongoing dialogue, demonstration lessons, and iterative feedback loops that model effective practice and scaffold competency growth (Ingersoll & Strong, 2011).

- Formative assessment of theory in practice relies on rubric-aligned observations, e-portfolios, and performance assessments to verify classroom competence and guide improvement (Buck et al., 2010; Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2020).

- Tight theory–practice links connect campus assignments with practicum tasks through case-based learning and field-anchored coursework, thereby reinforcing transfer (Furner & McCulla, 2019; Rasmussen & Rash-Christensen, 2015).

- University–school partnerships establish shared governance, reciprocal professional development, and joint supervision arrangements that align expectations and resources (Kimmelmann & Lang, 2019).

- Structured collaborative tasks such as team lesson planning, problem-based scenarios, and design thinking sprints deepen collective inquiry and shared understanding (Hadad et al., 2024).

- Equity focused role modelling sees faculty enact culturally responsive, democratic, and sustainability-oriented pedagogy, offering concrete templates for future classrooms (Altstaedter et al., 2016; Xie & Cui, 2021).

2.3. Technology-Enabled Continuity as a Future-Proof Strategy

2.4. Teacher Training Frameworks Under Recurrent Crises

Study Purpose and Research Questions

- RQ1. Which principles do policymakers and directors identify as essential for effective pre-service teacher preparation across face-to-face, online, and hybrid settings, particularly under conditions of disruption?

- RQ2. How do the two stakeholder groups differ in the priority they assign to these principles, reflecting both scholarly emphases and practical constraints?

- RQ3. To what extent do the interview-derived principles align with the established literature and with the capacities of the Crises Leadership Framework (CLF)?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments and Procedure

- An inductive, bottom-up thematic analysis. This method was used to identify the main topics and themes that emerged directly from the participants’ responses, without relying on a predefined coding framework (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Yin, 2015; Proudfoot, 2023). Through this inductive process, categories and subcategories were developed to reflect the key principles perceived as essential for effective TTPs.

- A deductive, top-down content analysis. Interview transcripts were systematically coded against two a priori schemes. The first comprised the ten evidence-based teacher training principles distilled by Hadad et al. (2023a)—(1) active, application-oriented coursework; (2) authentic field immersion; (3) structured reflection; (4) peer communities of practice; (5) expert mentoring; (6) formative assessment of theory in practice; (7) tight theory–practice links; (8) university–school partnerships; (9) structured collaborative tasks; and (10) equity-focused role-modelling. These are principles widely endorsed in the literature (Altstaedter et al., 2016; Buck et al., 2010; Ingersoll & Strong, 2011; Weber et al., 2018; Xie & Cui, 2021). The second scheme captured the six characteristics of the Crises Leadership Framework (CLF): crisis care, adaptive roles, stakeholder collaboration, multidimensional communication, complex decision-making, and contextual influences (Striepe & Cunningham, 2022). Each statement was coded on both axes—training principle and CLF characteristic—enabling direct comparison with mainstream teacher education research and simultaneous testing of alignment with a crisis leadership lens central to this study.

4. Results

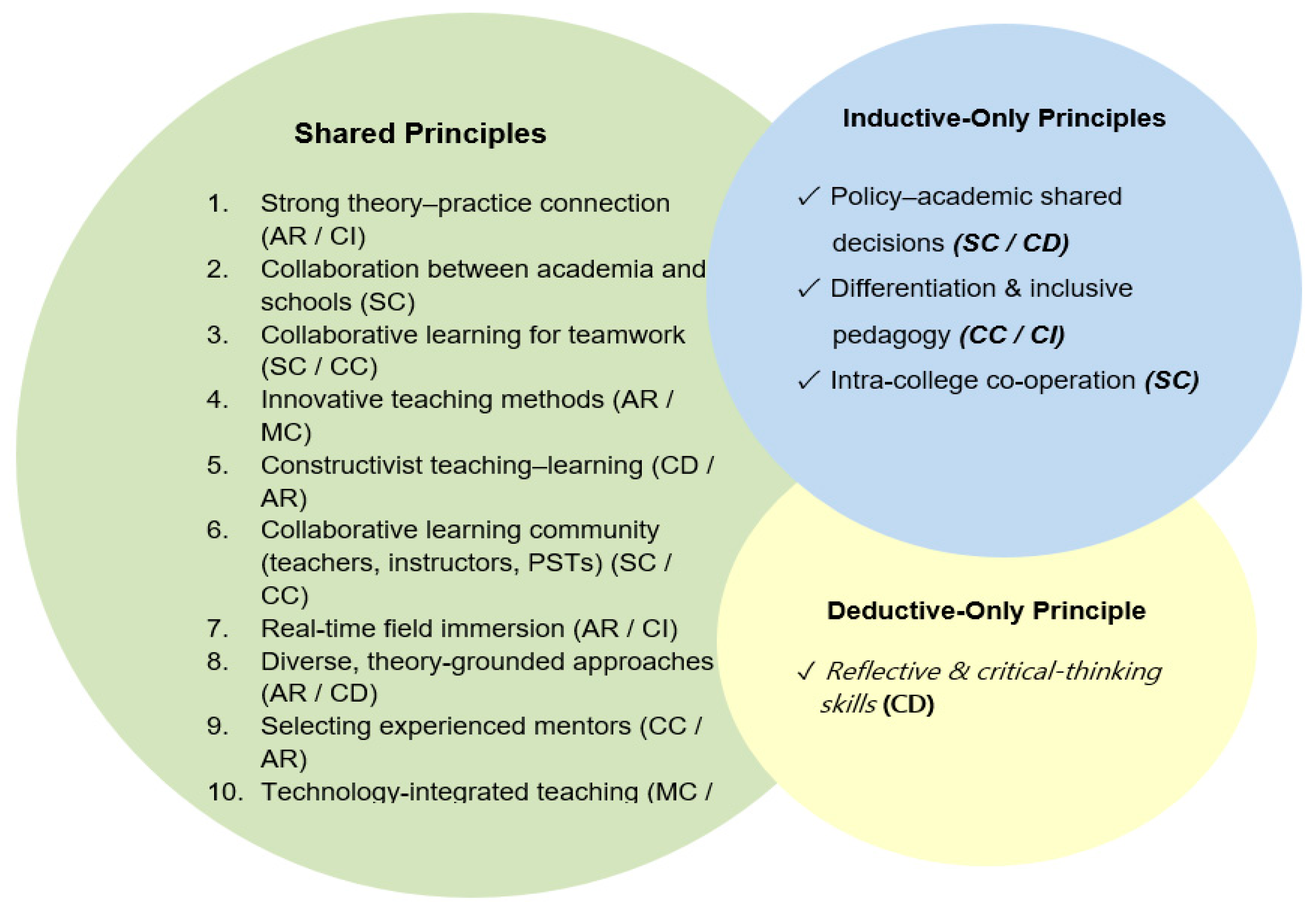

Integrating Inductive and Deductive Findings: Conceptual Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Convergence: Principles Shared Across Stakeholders and the Literature

5.2. Divergence: Unique Contributions from Policymakers and TTP Directors

5.3. Unspoken Priorities: Blind Spots in Professional Training Principles

6. Conclusions

- Curriculum development. Integrate theory with hands-on tasks, active engagement, and authentic fieldwork across delivery modes.

- Pedagogical approaches. Employ collaborative, constructivist, and inclusive strategies to meet diverse learner needs.

- Field experiences. Provide sustained school immersion, mentoring, and reflective practice—even in remote formats—to cultivate adaptive roles and crisis care.

- Assessment and feedback. Use continuous formative assessment to refine instructional decisions in real time.

- Collaborative partnerships. Strengthen college–school–mentor networks that can pivot together when disruptions occur.

- Policy–practice coordination. Foster joint decision-making between ministries and training institutions to align objectives and contingency plans.

- Technology integration. Embed digital literacy, simulation, and hybrid-learning design so that instructional continuity is feasible under lockdown or conflict.

- Crisis preparedness. Explicitly train pre-service teachers in the six CLF capacities—crisis care, adaptive roles, stakeholder collaboration, multidimensional communication, complex decision-making, and contextual awareness—to ensure resilience during future climate, health, or security emergencies.

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

Semi-Structured Elite Interview Protocol: Core Principles for Pre-Service Teacher Preparation

- Background Information

- Participant Type: [ ] Ministry of Education Policymaker [ ] Teacher Education Program Director

- Interview Duration: Approximately 30–45 min

- Introduction Script

- Interview Questions

- Essential Principles: What do you consider the most important principles for effective pre-service teacher training programs?

- Adaptation and Flexibility: How do you ensure these programs work effectively across different contexts and formats, and how do you adapt when circumstances change?

- Relationships and Support: What partnerships, collaborative relationships, and support systems are important for successful teacher preparation?

- Decision-Making and Crisis Response: How do you make decisions about program implementation, and how do you maintain quality and continuity during challenging or disruptive periods?

- Communication and Context: How do you address communication across different stakeholders and prepare teachers for diverse educational contexts?

- Additional Insights: Is there anything else about effective teacher preparation that you consider essential?

- Interview Protocol Notes

- Questions are designed to be open-ended to allow natural emergence of principles and priorities

- Questions 2–5 are strategically structured to potentially elicit responses across all six CLF capacities (adaptive roles, crisis care, stakeholder collaboration, multidimensional communication, complex decision-making, contextual influences) while maintaining organic conversation flow

- Use open-ended follow-up probes to encourage elaboration and specific examples

- Allow participants to guide the conversation toward their areas of emphasis

- Record all responses for subsequent inductive and deductive analysis using both the ten evidence-based training principles and the CLF

References

- Al Abiky, W. B. (2021). Lessons learned for teacher education: Challenges of teaching online classes during COVID-19, what can pre-service teachers tell us? Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 30(2), 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Altstaedter, L. L., Smith, J. J., & Fogarty, E. (2016). Co-teaching: Towards a new model for teacher preparation in foreign language teacher education. Hispania, 99, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O. (2016). A model of professional development: Teachers’ perceptions of their professional development. Teacher and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 22(6), 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Herscu, O. (2020). Formal professional development as perceived by teachers in different professional life periods. Professional Development in Education, 46(5), 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Shamir-Inbal, T. (2017). ICT Coordinaotrs’ TPACK-bades leadership knowledge in their roles as agents of change. Journal of Information Technology Education, 16(6), 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., & Zamir, S. (2024). Personalization in education. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. P. (2010). Children of reform: The impact of high-stakes education reform on preservice teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(5), 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, G. A., Trauth-Nare, A., & Kaftan, J. (2010). Making formative assessment discernable to pre-service teachers of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 47(4), 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A., & Monda-Amaya, L. (2016). Preservice teachers’ perceptions of challenging behavior. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39(4), 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A., & Nolen, A. (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 10(6), 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, Y. (2025). A scientometric study of pre-service teacher preparation for educational equity and social justice. Teaching Education, 36(1), 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K. M. (2021). Chi-square automatic interaction detection analysis of qualitative data. In The Routledge reviewer’s guide to mixed methods analysis (pp. 69–76). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., & Sáez-López, J. M. (2016). Game-based learning and gamification in initial teacher training in the social sciences: An experiment with MinecraftEdu. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Ramot, R. (2020). Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexhage, J., Leiss, D., Schmidt, T., & Ehmke, T. (2016). The connected classroom: Using videoconferencing technology to enhance teacher training. Reflecting Education, 10, 70–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fakis, A., Hilliam, R., Stoneley, H., & Townend, M. (2014). Quantitative analysis of qualitative information from interviews: A systematic literature review. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 8(2), 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, D., Smits, A., & Voogt, J. (2019). Technology integration of pre-service teachers explained by attitudes and beliefs, competency, access, and experience. Computers & Education, 130, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M. A. (2020). Preparing teachers to teach in complex settings: Opportunities for professional learning and development. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M. A., Santos, P., Fernandes, S., & Pereira, D. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ views of their training: Key issues to sustain quality teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 16(2), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furner, C., & McCulla, N. (2019). An exploration of the influence of school context, ethos and culture on teacher career-stage professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 45(3), 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, M. (2018). Reproduction, contradiction and conceptions of professionalism: The case of pre-service teachers. In Critical studies in teacher education (pp. 86–129). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, E. F., & Swayze, S. (2012). In-depth interviewing with healthcare corporate elites: Strategies for entry and engagement. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(3), 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, K. (2002). Getting in the door: Sampling and completing elite interviews. PS: Political Science & Politics, 35(4), 669–672. [Google Scholar]

- Grinshtain, Y., & Salman, H. (2023). Intensive training programme for pre-service teachers: An intersectionality perspective of an Israeli rural druse school. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 14(6), 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S. (2025). Learning in crisis: Self-regulation, routine-facilitated well-being, and academic stress among higher education students. Metacognition and Learning, 20(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S., Avidov-Ungar, O., Shamir-Inbal, T., Amir, A., Blau, I., & Or Griff, T. (2023a, June 26–27). Effective principles for pre-service teacher training in hybrid environments. The Eighth International Conference on Teacher Education Passion and Professionalism in Teacher Education, Tel Aviv, Israel. Available online: https://virtual.oxfordabstracts.com/#/event/2334/submission/134 (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Hadad, S., & Deshen, M. (2025). Adapting to crisis: Assessing teacher self-efficacy, stability, and ICT support within emergency remote teaching and learning environments. Learning Environments Research, 28(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Blau, I. (2024). Pedagogical strategies employed in the emergency remote learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: The tale of teachers and school ICT coordinators. Learning Environments Research, 27, 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S., Watted, A., & Blau, I. (2023b). Cultural background in digital literacy of elementary and middle school students: Self-appraisal versus actual performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W. S. (2011). Strategies for conducting elite interviews. Qualitative Research, 11(4), 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, F. M., Downer, J. T., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Association of pre-service teachers’ performance, personality, and beliefs with teacher self-efficacy at program completion. Teacher Education Quarterly, 39(4), 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, P. (2024). Discussing critical civic education dilemmas with pre-service elementary teachers as a form of democratic education. The New Educator, 21, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmelmann, N., & Lang, J. (2019). Linkage within teacher education: Cooperative learning of teachers and student teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, C. (2023). A complex unit interviews analysis approach in qualitative social work research. The British Journal of Social Work, 53, 3258–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriewaldt, J., & Turnidge, D. (2013). Conceptualising an approach to clinical reasoning in the education profession. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(6), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, G. (2017). Implementing the flipped classroom in teacher education: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Natow, R. S. (2020). The use of triangulation in qualitative studies employing elite interviews. Qualitative Research, 20(2), 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, K. (2023). Inductive/deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(3), 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J., & Rash-Christensen, A. (2015). How to improve the relationship between theory and practice in teacher education? Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 14(3), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, K., & Schrittesser, I. (2021). Using the Service-Learning approach to bridge the gap between theory and practice in teacher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. (1996). Elite interviewing: Approaches and pitfalls. Politics, 16(3), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roller, M. R., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rots, I., Aelterman, A., Vlerick, P., & Vermeulen, K. (2007). Teacher education, graduates’ teaching commitment and entrance into the teaching profession. Teaching and Teacher education, 23(5), 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Caballe, A., Esteve-Mon, F. M., & Gonzalez-Martinez, J. (2020). What to expect when you are simulating? About digital simulation potentialities in teacher training. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design, 10, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, I., Kalir, D., & Malkinson, N. (2020). The role of pedagogical practices in novice teachers’ work. European Journal of Educational Research, 9(2), 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayir, M. F., Aydin, N., & Aydeniz, S. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on pre-service teachers’ teaching practice. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 10(3), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, D. (2015). Your chi-square test is statistically significant: Now what? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 20(8), 1–10. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1059772.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Striepe, M., & Cunningham, C. (2022). Understanding educational leadership during times of crises: A scoping review. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(2), 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumantri, M. S., Prayuningtyas, A. W., Rachmadtullah, R., & Magdalena, I. (2018). The roles of teacher-training programs and student teachers’ self-regulation in developing competence in teaching science. Advanced Science Letter, 24, 7077–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir, M. Z., Iqbal, M. Z., & Asghar, M. Z. (2020). A study of the significant factors affecting pre-service teacher education in Turkey. Bulletin of Education and Research, 42(1), 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. W., & Ringlaben, R. P. (2012). Impacting pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. Higher Education Studies, 2(3), 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., Forkosh-Baruch, A., Prestridge, S., Albion, P., & Edirisinghe, S. (2016). Responding to challenges in teacher professional development for ICT-integration in education. Educational Technology & Society, 19(3), 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H. U. (2024). Environmental education in preschool teacher training program: A systematic review. Natural Sciences Education, 53(2), e20154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, T., Sointu, E., Kukkonen, J., Kontkanen, S., Lambert, M. C., & Mäkitalo-Siegl, K. (2017). TPACK updated to measure pre-service teachers’ twenty-first century skills. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(3), 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K. E., Gold, B., Prilop, C. N., & Kleinknecht, M. (2018). Promoting pre-service teachers’ professional vision of classroom management during practical school training: Effects of a structured online-and video-based self-reflection and feedback intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., & Cui, Y. (2021). Preservice teachers’ implementation of formative assessment in English writing class: Mentoring matters. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative research from start to finish. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yustina, Y., Syafii, W., & Vebrianto, R. (2020). The effects of blended learning and project-based learning on pre-service biology teacher’s creative thinking through online learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. Jurnal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia, 9(3), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Watterston, J. (2021). The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. Journal of Educational Change, 22(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inductive Analysis | Deductive Analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Total | SR | Policymakers | TTP Directors | Presence in the Literature | Mapped CLF Characteristic(s) | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Establishing a strong connection between theoretical knowledge and practical application | 113 | 44.1% | +8.82 | 43 | 38% | 70 | 62% | Yes (#7) | Adaptive roles; contextual influences |

| SR = +4.29 | SR = −2.15 | ||||||||

| X2(1) = 21.90, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Collaboration between academic institutions and training schools | 49 | 19.1% | −0.20 | 11 | 24% | 38 | 76% | Yes (#8) | Stakeholder collaboration |

| SR = +0.38 | SR = −0.19 | ||||||||

| X2(1) = 0.06, p = 0.80 | |||||||||

| Collaborative learning as a preparation for collaborative teaching | 45 | 17.6% | −1.18 | 6 | 13% | 39 | 87% | Yes (#9) | Complex decision-making; adaptive roles |

| SR = −1.00 | SR = +0.50 | ||||||||

| X2(1) = 0.88, p = 0.86 | |||||||||

| Preparing PSTs for teaching through innovative methods | 28 | 10.9% | −3.3 | 5 | 18% | 23 | 82% | Partially (#1, #10) | Adaptive roles; multidimensional communication |

| SR = −0.25 | SR = +0.13 | ||||||||

| X2(1) = 0.02, p = 0.97 | |||||||||

| Preparing PSTs for constructivist teaching–learning | 21 | 8.2% | −4.14 | 8 | 38% | 13 | 62% | Partially (#1, #2, #10) | Stakeholder collaboration |

| SR = +1.5 | SR = −0.93 | ||||||||

| X2(1) = 3.24, p = 0.072 | |||||||||

| X2(4) = 107.21, p = 0.001 | |||||||||

| Inductive Analysis | Deductive Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Total | Standardized Residuals | Presence in the Literature | Mapped CLF Characteristic(s) | |

| N | % | ||||

| Collaboration and shared decision-making between policymakers and higher education institutions in determining policies | 35 | 76.1% | +2.50 | No | Stakeholder collaboration; complex decision-making |

| Creating a collaborative learning community involving teachers, instructors, and pre-service teachers (PSTs) | 11 | 23.9% | −2.50 | Partially (#4, #10) | Stakeholder collaboration; crisis care |

| X2(1) = 11.5, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Inductive Analysis | Deductive Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Total | Standardized Residuals | Presence in the Literature | Mapped CLF Characteristic(s) | |

| N | % | ||||

| Real-time field observations and authentic experience | 68 | 27.4% | +6.65 | Yes (#2) | Adaptive roles; contextual influences |

| Providing feedback and formative assessment for the PSTs | 62 | 25.0% | +5.57 | Yes (#6) | Crisis care; adaptive roles |

| Preparing PSTs for differentiation and inclusive education | 24 | 15.7% | +1.44 | No | Crisis care; contextual influences |

| Cooperation and collaboration within the college team | 21 | 8.5% | −1.80 | No | Stakeholder collaboration |

| Offering a diverse range of teaching approaches supported by a solid theoretical foundation | 20 | 8.1% | −1.98 | Yes (#1, #2, #4, #10) | Adaptive roles; complex decision-making |

| Choosing highly experienced teacher trainers | 16 | 6.5% | −2.69 | Yes (#5) | Crisis care; adaptive roles |

| Utilizing classroom simulation for peer and instructor evaluations | 12 | 4.8% | −3.41 | Yes (#1, #2, #6) | Multidimensional communication; complex decision-making |

| Preparation for integrated technology teaching | 10 | 4.0% | −3.77 | Partially (#1, #10) | Multidimensional communication; adaptive roles |

| X2(7) = 0.117, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Inductively Emerged Principle | Deductive Findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Presence in the Literature | Dominant CLF Characteristic(s) | |

| Strong theory–practice connection | ✔ Close links between theory and practice (#7) | Adaptive roles/contextual influences |

| Collaboration between academia and schools | ✔ HE–school cooperation (#8) | Stakeholder collaboration |

| Collaborative learning for future teamwork | ✔ Collaborative opportunities (#9) | Stakeholder collaboration/crisis care |

| Innovative teaching methods | ▲ Active learning; role-modelling (#1, #10) | Adaptive roles/multidimensional communication |

| Constructivist teaching–learning | ▲ Active learning; field immersion (#1, #2) | Complex decision-making/adaptive roles |

| Policy–academic shared decision-making | ✘ Not in framework | Stakeholder collaboration/complex decision-making |

| Collaborative learning community (teachers–instructors–PSTs) | ▲ Peer community; role-modelling (#4, #10) | Stakeholder collaboration/crisis care |

| Real-time field immersion | ✔ Authentic experience (#2) | Adaptive roles/contextual influences |

| Formative feedback and assessment | ✔ Skill-application assessment (#6) | Crisis care/adaptive roles |

| Differentiation and inclusive pedagogy | ✘ Not in framework | Crisis care/contextual influences |

| Intra-college cooperation | ✘ Not in framework | Stakeholder collaboration |

| Diverse, theory-grounded teaching approaches | ✔ Multiple principles (#1, #2, #4, #10) | Adaptive roles/complex decision-making |

| Selecting experienced mentors | ✔ Experienced coaching teachers (#5) | Crisis care/adaptive roles |

| Classroom simulation for peer/instructor evaluation | ✔ Multiple principles (#1, #2, #6) | Multidimensional communication/complex decision-making |

| Preparation for technology-integrated teaching | ▲ Active learning; role-modelling (#1, #10) | Multidimensional communication/adaptive roles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadad, S.; Blau, I.; Avidov-Ungar, O.; Shamir-Inbal, T.; Amir, A. Continuity and Quality in Pre-Service Teacher Preparation Across Modalities: Core Principles in a Crisis Leadership Framework. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101355

Hadad S, Blau I, Avidov-Ungar O, Shamir-Inbal T, Amir A. Continuity and Quality in Pre-Service Teacher Preparation Across Modalities: Core Principles in a Crisis Leadership Framework. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101355

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadad, Shlomit, Ina Blau, Orit Avidov-Ungar, Tamar Shamir-Inbal, and Alisa Amir. 2025. "Continuity and Quality in Pre-Service Teacher Preparation Across Modalities: Core Principles in a Crisis Leadership Framework" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101355

APA StyleHadad, S., Blau, I., Avidov-Ungar, O., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Amir, A. (2025). Continuity and Quality in Pre-Service Teacher Preparation Across Modalities: Core Principles in a Crisis Leadership Framework. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101355