Is Peace Education out of Style? The (Im)Possibilities of a Transformative Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Peace Education as Transformative Education

3.1. Peace Education: Concept and Transformative Practice

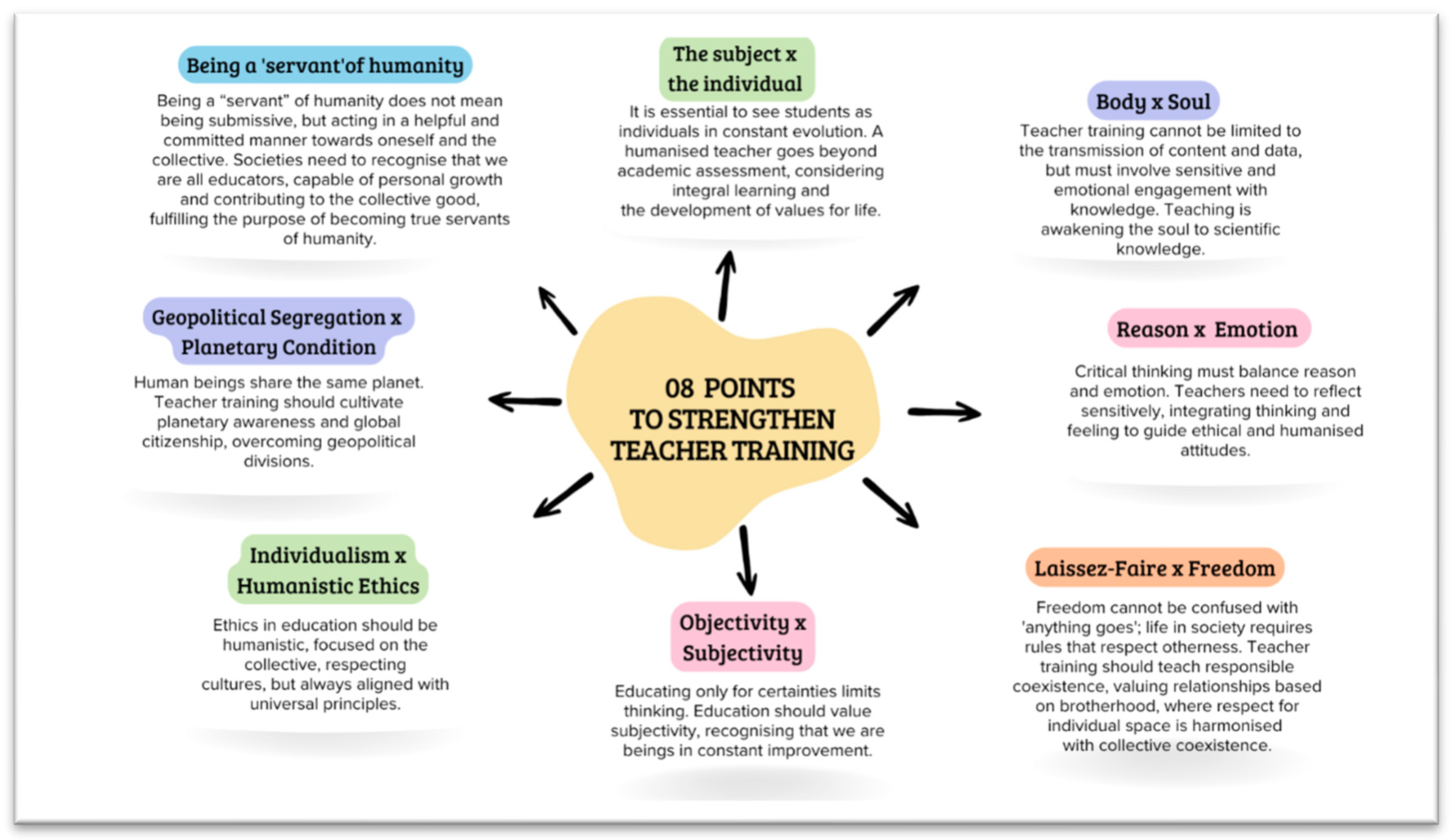

3.2. Teacher Training for Peace Building

4. Historical Journey: Boom and Decline of Peace Studies

But more than that, recent years have added to this loss of conceptual and discursive vigor in Peace Studies a progressive recovery of the dominant position of traditional discourses: the realist discourse, for which peace is always and only the peace of the victors (military, ultimately), and the liberal discourse, for which peace is the result of the standardization of forms of political and economic governance according to the (liberal) model of the dominant countries in the world system.

5. The New Global Agenda: The Centrality of Citizenship Education

6. Global Policies and National Contexts: Portugal and Brazil

6.1. Context in Portugal

6.2. Context in Brazil

The rise of extremism and its dissemination through digital media that promote various forms of discrimination; the lack of control and criminalization of hate speech and practices; the promotion of a gun culture and the glorification of violence; the prevalence of bullying, prejudice and discrimination in the school environment and insufficient professional training to deal with issues such as conflict mediation.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UDHR | Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UN | United Nations |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goals |

| GCE | Global Citizenship Education |

| ENEC | The National Strategy for Citizenship Education |

| CeD | Citizenship and Development |

| PPCs | Pedagogical Course Plans for Pedagogy |

| LDB | National Education Guidelines and Bases Law |

| PNE | National Education Plan PNE |

| MEC | Ministry of Education Brazil |

| 1 | Various conflicts and wars are currently raging on planet Earth. The most prominent include the war between Israel and Hamas, the war between Russia and Ukraine and the civil conflicts in Sudan and Yemen. In addition to these, there are other tensions in countries such as Myanmar, Nigeria and Syria, and in regions such as the Sahel (an arid transitional region south of the Sahara Desert), and the Horn of Africa (a peninsula in the east of the African continent). |

| 2 | Two important documents stand out as milestones prior to 1999: 1. The Seville Declaration (or Manifesto) (1986): convened by UNESCO in the city of Seville, Spain, this conference brought together experts with the aim of combating the use of biology as a justification for violence and war. As a result, the “Seville Manifesto” was drawn up, a document which states that violence is a product of culture (Adams, 1995). 2. Convention on the United Nations (1989): this international treaty establishes the fundamental rights of all children, including the right to education, and is an essential instrument for guaranteeing children’s access to education, as well as their protection against all forms of violence and exploitation. |

| 3 | In this historical journey, even before the SDG were formulated, the international community had already agreed on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, aimed at eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, promoting gender equality, improving basic education and reducing child mortality, among other commitments. Although less wide-ranging than the SDGs, these goals also had a dialog with overcoming structural, cultural and direct violence, since poverty reduction, access to education and the promotion of equality contributed to dismantling mechanisms of exclusion and inequality that fuel conflicts and social injustices. |

| 4 | The text mentions Peace Education, Education for Citizenship, Global Citizenship Education and Human Rights Education in several places. In this sense, we emphasize the distinction between them for clarification purposes. Strictly speaking, Human Rights Education aims to prevent abuses and violations by creating a universal culture of human rights. Education for Citizenship aims to train active and responsible citizens who are aware of their rights and duties and capable of participating in democratic life. Global Citizenship Education aims to empower people of all ages with the values, knowledge and skills to be responsible global citizens who promote a more just, peaceful, sustainable and inclusive world. Peace Education seeks to develop skills for non-violent conflict resolution, emphasizing overcoming violence and building a culture of peace and a culture of non- violence. They are therefore related areas. |

| 5 | The Revolution of 25 April 1974, known as the Carnation Revolution, a military movement led by captains, put an end to the Estado Novo dictatorship and inaugurated a new stage in Portuguese history, geared towards democracy, social justice and the decolonization of African territories. Inspired by the ideals of freedom, the April Revolution was reflected in artistic expressions such as Sérgio Godinho’s song, which stated that there would only be “Real freedom when there is peace, bread, housing, health and education”. In this context, education came to be recognized as a fundamental pillar in the construction of a democratic state governed by the rule of law, and schools were given the responsibility of forming aware, critical and participatory citizens. Several reforms were then implemented: among them, the replacement of the subject of Political and Administrative Organization of the Nation with “Introduction to Politics” (1974–75), and the creation of the Student Civic Service and Civic and Polytechnic Education in the new Unified Secondary Education. However, many of these initiatives were short-lived and had limited impact. In 1984, the introduction of Civic Education was also proposed, but its implementation never materialized. The 1986 Basic Law of the Education System (LBSE) was a milestone in the restructuring of the education system, reinforcing the commitment to the democratization of education and the formation of an active and participatory citizenry. From 1989, with Decree-Law 286/89, the areas of Personal and Social Development, School-Area and Complementary Curricular Activities (ACC) were created, reinforcing students’ personal and civic training. In 1998, the Ministry of Education highlighted citizenship as an integrating axis of the curriculum, which prepared the ground for the curriculum reorganization of 2001, through Decree-Laws 6 and 7, which integrated Citizenship Education across the board in basic and secondary education (Machado, 2024, pp. 16–20). |

| 6 |

References

- Adams, D. (1995). El Manifiesto de Sevilla sobre la violencia: Preparar el terreno para la construcción de la paz. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Adan, M. Y. (2025). The role of peace education in promoting social justice and sustainable peace in post-conflict societies: A 4Rs framework analysis. Frontiers in Political Science, 7, 1650027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida Cravo, T. (2017). A consolidação da paz: Pressupostos, práticas e críticas. JANUS.NET e-Journal of International Relations, 8(1), 47–64. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11144/3032 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Andreotti, V. (2006). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 3, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bacher, S. V., Kraler, C., & Binytska, K. (2024). Enlightened ideas for modern peace education. From Kant to Humboldt. Humanitarian Studies: History and Pedagogy, 2, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookchin, M. (1991). The ecology of freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy (Rev. ed). Black Rose Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Senado Federal.

- Brasil. (1990). Lei nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990: Dispõe sobre o estatuto da criança e do adolescente e dá outras providências (seção 1). Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil. (1996). Decreto 1.904: Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos—PNDH-1. Available online: http://www.dhnet.org.br/dados/pp/pndh/textointegral.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2002). Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos—PNDH II. Available online: https://dspace.mj.gov.br/handle/1/14019 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2006). Plano Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos (PNEDH). Available online: https://www.dhnet.org.br/dados/pp/edh/br/pnedh2/pnedh_2.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2009). Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos—PNDH III. Secretaria de Direitos Humanos. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/decreto/d7037.htm (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2014a). Decreto-Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014: Plano Nacional de Educação 2014–2024 (PNE). Câmara dos Deputados. Edições Câmara. Available online: https://pne.mec.gov.br/17-cooperacao-federativa/31-base-legal (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2014b). Lei nº 13.010, de 26 de junho de 2014: Altera a Lei nº 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990, para estabelecer o direito da criança e do adolescente de serem educados e cuidados sem o uso de castigos físicos ou de tratamento cruel ou degradante (seção 1). Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil. (2016). Projeto de Lei nº 5.826, de 2016: Institui a política nacional de prevenção e combate ao bullying e dá outras providências. Available online: https://www.camara.leg.br (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Brasil. (2017). Lei nº 13.431, de 4 de abril de 2017: Estabelece o sistema de garantia de direitos da criança e do adolescente vítima ou testemunha de violência (seção 1). Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil. (2018). Lei nº 13.663, de 14 de maio de 2018: Altera o art. 12 da Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, para incluir a promoção de medidas de conscientização, de prevenção e de combate a todos os tipos de violência e a promoção da cultura de paz entre as incumbências dos estabelecimentos de ensino. Diário Oficial da União.

- Brasil. (2019). Lei nº 13.935, de 11 de dezembro de 2019: Dispõe sobre a prestação de serviços de psicologia e de serviço social nas redes públicas de educação básica (seção 1). Diário Oficial da União.

- Cabezudo, A. (2020). Pedagogia para a cultura de paz, cidadania e direitos humanos: Uma construção que apela à memória e à justiça. Revista Educar Mais, 4(3), 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Santos, A. F., Prado De Sousa, C., & Serrano Oswald, S. E. (2023). Tendências & desafios dos estudos em educação para a paz no Brasil. Educação Unisinos, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2010). Projeto de pesquisa: Métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto (3rd ed., Vol. 13). Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Damião, M. H. (2016). Os mesmos direitos a todos os cidadãos. A educação para a paz no currículo escolar. Revista de Estudos Curriculares, 7(2), 3–17. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:185696417 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Ferreira, N. S. A. (2002). As pesquisas denominadas «estado da arte». Educação & Sociedade, 23(79), 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floro, B. M. (2025). Contextualizing peace education: Towards a framework for transformative and sustainable peace. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394511191_Contextualizing_Peace_Education_Towards_a_Framework_for_Transformative_and_Sustainable_Peace (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Foucault, M. (1986). Microfísica do poder. Graal. Graal. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1987). Pedagogia do oprimido. Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2021). Educação como prática da liberdade. Editora Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Freire Nita, A. M. A. (2006). Educação para a paz segundo Paulo Freire. Educação, 29(2), 387–393. Available online: https://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/faced/article/view/449 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Galtung, J. (1964). An editorial. Journal of Peace Research, 1(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, J. (1976). Three approaches to peace: Peacekeeping, peacemaking and peacebuilding. In J. Galtung (Ed.), Essays in peace research (Vol. 2, pp. 282–304). Ejlers. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J. (2003). Paz por medios pacíficos: Paz y conflicto, desarrollo y civilización. Bakeaz. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C. C., Sanchez, M. H., Silva, F. M. D., & Mandelli, A. (2024). Reação patriarcal: Construções masculinas e o rearmamento da direita. Ponto-e-Vírgula, 1(35), e66487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jares, X. R. (2002). Educacao para a paz: Sua teoria e sua pratica (2nd ed.). Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Jares, X. R. (2021). Educar para a verdade e para a esperança. Artmed. [Google Scholar]

- Kastein, K. (2025). Evolution of peace education. In M. C. Hallward, J. E. Kim, & C. Mouly (Eds.), The sage handbook of peace and conflict studies (pp. 211–222). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederach, J. P. (2003). Little book of conflict transformation: Clear articulation of the guiding principles by a pioneer in the field. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, J. P. (2008). Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures (1. paperback ed.). [Nachdr.]. Syracuse Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, J. P. (2012). Transformação de conflitos. Palas Athena Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Löwy, M. (2023). Nine theses on ecosocialist degrowth. Monthly Review, 75, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, S. M. F., Nogueira Magalhães, K. I., & Souza, J. M. D. (2023). Educação para a cultura de paz e formação de professores. Revista de Iniciação à Docência, 8(1), e11675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M. C. R. (2024). Práticas de educação para a cidadania na escola: As perspetivas de crianças e jovens [Dissertação de Mestrado, Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação, Universidade do Porto]. Repositório da Universidade do Porto. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/164427 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Magalhães, S. M. O. (2014). O “ser solidário” e a construção da cultura de paz. Dialogia, 18, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayo, M. C. D. S. (2009). Construção de indicadores qualitativos para avaliação de mudanças. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 33(Suppl. 1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da educação Brasil. (2024). Boletim: Dados sobre violências nas escolas. Coordenação-geral de acompanhamento e combate à violência nas escolas. Secdi. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mec/pt-br/escola-que-protege/BOLETIMdadossobreviolenciasnasescolas.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Ministério da educação Portugal. (2016). Estratégia nacional de educação para a cidadania. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Projetos_Curriculares/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/estrategia_cidadania_original.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Muñoz, F. A. (2001). La paz imperfecta. Editorial Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, A. M., Seixas, A. M., & Souza, B. D. (2019). Evolução política da educação para a cidadania a nível supranacional e nacional: Uma análise documental. In Atas do XIV congresso da SPCE: Ciências, culturas e cidadanias (pp. 36–45). Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G. C. (2017). Estudos da paz: Origens, desenvolvimentos e desafios críticos atuais. Carta Internacional, 12(1), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Malta, M., Kelly Galvão, V., & Costa Ferreira Lemos, R. (2025). A cultura de paz nas produções científicas nos últimos xx anos: Uma revisão sistemática. SciELO Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, A., & Costa, M. (2020). An ideology critique of global citizenship education. Critical Studies in Education, 61(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma Valenzuela, A. (2009). Profesorado y educación para la paz. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 43(2), 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal. (2001). Decreto-Lei n.º 6/2001, de 18 de janeiro: Princípios orientadores da organização, gestão e desenvolvimento do currículo do ensino básico. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/analisejuridica/decreto-lei/6-2001-338986 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Portugal. (2011). Decreto-Lei n.º 50/2011, de 8 de abril (pp. 2097–2126). Diário da República. n.º 70—I Série.

- Portugal. (2012). Decreto-Lei n.º 139/2012, de 5 de julho (pp. 3476–3491). Diário da República. n.º 129—I Série.

- Pureza, J. M. (2014). A paz e os direitos humanos já não são o que eram: Desafios para a educação. Nova Ágora—CFAE. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10316/99663 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pureza, J. M. (2018). O desafio crítico dos estudos para a paz. Organicom, 15(74–89), 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pureza, J. M. (2024). A “Terceira Guerra Mundial em pedaços” e o desafio aos Estudos para a Paz. In E. Pinto da Costa, A. M. Costa e Silva, A. de Oliveira Martins, L. Lima, & C. Madureira (Eds.), Mediação e construção da convivência e da paz (pp. 8–14). Edições Universitárias Lusófonas. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, B. (2001). Education for a culture of peace in a gender perspective. UNESCO Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S. E., Donges, J. F., Drüke, M., Fetzer, I., Bala, G., Von Bloh, W., Feulner, G., Fiedler, S., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Hofmann, M., Huiskamp, W., Kummu, M., Mohan, C., Nogués-Bravo, D., … Rockström, J. (2023). Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances, 9(37), eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabán Vera, C. (2003). La labor de la Unesco en educación para la paz. In F. A. Muñoz Muñoz, B. Molina Rueda, & F. Jiménez Bautista (Eds.), Actas del i congreso hispanoamericano de educación y cultura de paz (pp. 341–359). Editorial Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M. N. I., Hanum, F., & Rukiyati. (2025). Approaches to implementing peace education in high schools for nonviolent conflict resolution. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2553004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles Filho, N. A., & Salles, V. O. (2018). Cultura de paz como componente da lei de diretrizes e bases da educação nacional: Dilemas e possibilidades. Publicatio UEPG: Ciencias Sociais Aplicadas, 26(2), 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. M. M., & Tavares, C. (2013). Educação em direitos humanos no Brasil: Contexto, processo de desenvolvimento, conquistas e limites. Educação, 36(1), 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, C. P. (2023). Educar para paz e não violência: Um estudo comparativo entre Brasil e Portugal. In Dossiê Contribuições Acadêmicas no Eixo Portugal—Brasil Diálogos e Interseções (pp. 135–145). MIL/DG Edições. Coletivo de Pesquisadores Brasileiros em Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, E. B. (2025). Formadores integrais para crianças integrais: Uma análise dos currículos dos cursos de Pedagogia do Brasil no quadro dos direitos humanos [Doctoral thesis, Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação da Universidade de Coimbra]. [Google Scholar]

- Torrego, J. C. S. (2013). Mediación de conflictos en instituciones educativas: Manual para la formación de mediadores (7th ed.). Narcea. [Google Scholar]

- Trancoso, A. E. R., & Oliveira, A. A. S. (2014). Produção social, histórica e cultural do conceito de juventudes heterogêneas potencializa ações políticas. Psicologia & Sociedade, 26(1), 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/unga/1989/en/18815 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Velez De Castro, F., & De Figueiroa-Rego, M. J. (2024). O pensamento crítico no ensino de geografia: Construção dialética a partir de um exercício filosófico. Cadernos de Geografia, 50, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Procedural Objective | Central Provocation | Skills Developed | Associated Value | Correspondence to UDHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developing practical and social skills, such as communication, creativity, group work, and self-knowledge | How can we get along better with others and develop our personal skills in groups? | Communication, collaboration, self-knowledge, creativity | Empathy, cooperation, autonomy, mutual respect | Article 1—All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

| Connecting theory and practice, allowing students to experience real and symbolic situations related to peace and social transformation | How can knowledge be transformed into action that promotes the common good? | Citizen responsibility, practical application of knowledge, ethical thinking | Peace, social transformation, solidarity | Article 29, §1—The individual has duties towards the community, where the free and full development of their personality is possible. |

| Stimulating critical thinking by analyzing information, making decisions and building alternatives to social problems | How can we analyze reality and propose fairer and more ethical solutions? | Critical thinking, decision-making, and ethical argumentation | Critical reflection, social responsibility, justice | Article 26, §2—Education shall aim at the full development of the human personality and the strengthening of human rights and fundamental freedoms. |

| Procedural Objective | Central Provocation | Skills Developed | Associated Value | Correspondence to UDHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proving the various methods of non-violent conflict resolution | What peaceful ways can we use to deal with everyday conflicts? | Conflict resolution, mediation, active listening | Non-violence, dialog, tolerance | Article 3—Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person. |

| Intending peaceful attitudes in everyday life, such as co-operation, empathy, and non- violent conflict resolution | How can we cultivate attitudes of peace in our daily actions? | Empathy, ethical attitudes, peaceful coexistence | Active peace, respect, understanding, solidarity | Article 28, §1-Everyone has the right to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized. |

| Representing alternative worlds to the ones we know today | How can we imagine and build more just and humane realities? | Critical vision, complex problem-solving, creativity | Critical awareness, hope, freedom, social responsibility | Article 27, §1—Everyone has the right to take part freely in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific progress and its benefits. |

| Aspect | Global Citizenship Education Soft | Global Citizenship Education Critical |

|---|---|---|

| Problem | Poverty, helplessness. | Inequality, injustice. |

| Nature of the problem | Lack of ‘development’, education, resources, skills, culture, technology, etc. | Complex structures, systems, assumptions, and power relations that create and maintain exploitation and forced weakening tend to eliminate difference. |

| Justification for the existence of privileged positions (in the North and South) | ‘Development’, ‘history’, education, harder work, better organization, better use of resources, technology. | Benefit from and control of unjust and violent systems and structures. |

| Basis for concern Common humanity/being good/sharing and caring. | Responsibility for the other (or for teaching the other). Justice/complicity in problems. | Responsibility towards others (or learning from others)—accountability. |

| Motives for action | Humanitarian/moral (based on normative principles for thought and action). | Political/ethical (based on normative principles for relationships). |

| How change happens | From the outside in (imposed change). | From the inside out. |

| Objective of global citizenship education | To enable individuals to act (or become active citizens) in accordance with what has been defined for them as a good life or an ideal world. | To enable individuals to critically reflect on the legacies and processes of their cultures, to imagine different futures and to take responsibility for decisions and actions. |

| Year | Measure/Decree-Law | Description | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Decree-Law no. 6/2001 | Introduction of Citizenship Education (EpC) was established as a curricular area to be addressed transversally throughout the curriculum. | Initial phase (2001) |

| 2011 | Decree-Law no. 50/2011 | Creation of the subject Civic Training in the 10th grade, criticized for its normative and transmissive approach to citizenship. | Institutional retreat (2011–2012) |

| 2012 | Decree-Law no. 139/2012 | Civic Education is abolished as a formal subject. CVE becomes transversal, with decentralized implementation by schools. | Institutional retreat (2011–2012) |

| 2015 | Paris Declaration and international guidelines | Reinforcement of the role of democratic and global citizenship in education as a response to social and political challenges. | Supranational |

| 2016–2018 | Curriculum guidelines and reforms | Creation of the Citizenship and Development subject, mobilizing schools to revitalize EpC with a focus on participatory practices. | Resumption (2016–2018) |

| Year | Measure/Decree-Law | Description | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Citizen Constitution | Constitution of the Republic of Brazil of 1988, art. 227, which determines that the family, society, and the State have the duty to guarantee the rights of children and adolescents, such as life, health, education, leisure, dignity, and family life, and to protect them from all forms of neglect, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty, and oppression. | Legal/Human Rights |

| 1990 | Legislation— Child Protection | Statute of the Child and Adolescent (ECA), Law No. 8.069 of 1990, linked to the principles and guidelines of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the dictates of the 1988 Federal Constitution. | Legal/Child Protection |

| 1999 | Culture of Peace— UN | Resolution 53/243 on the Declaration on a Culture of Peace, approved by the UN | Supranational |

| 2000 | Culture of Peace— UNESCO | Manifesto 2000 for a culture of peace and non-violence | Supranational |

| 2003 | Human Rights and Education | National Plan for Human Rights Education (PNEDH) | Educational/ Human Rights |

| 2008 | Peace Education— UNESCO | UNESCO Programme: Opening spaces | Educational/ Cultural |

| 2014 | Legislation— Child Protection | Law No. 13.010, of 26 June 2014, the “Spanking Law” or “Menino Bernardo Law”, amending the ECA (article 18, definition of physical punishment and cruel or degrading treatment). | Legal/Child Protection |

| 2016 | Combating School Violence | Bill 5.826/2016: combating violence, with an emphasis on bullying. | Legal/School Protection |

| 2017 | Specialized Protection and Listening | Law No. 13.431/2017, aimed at guaranteeing rights in the context of violence against children and adolescents. | Legal/Child Protection |

| 2017 | Education and Health | Health at School Programme (PSE)—a strategy to integrate health and education for the development of citizenship and the qualification of Brazilian public policies. | Health/ Educational |

| 2018 | Education and School Coexistence | Amendment to art. 12 of the LDB by Law no. 13.663 of 14 May 2018. | Educational/ Coexistence |

| 2019 | School Support Services | Law No. 13.935, of 11 December 2019, provides for psychology and social work services in public basic education networks. | Mental health/Social Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prudenciano de Souza, C.; Velez de Castro, F. Is Peace Education out of Style? The (Im)Possibilities of a Transformative Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101293

Prudenciano de Souza C, Velez de Castro F. Is Peace Education out of Style? The (Im)Possibilities of a Transformative Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101293

Chicago/Turabian StylePrudenciano de Souza, Cristiane, and Fátima Velez de Castro. 2025. "Is Peace Education out of Style? The (Im)Possibilities of a Transformative Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101293

APA StylePrudenciano de Souza, C., & Velez de Castro, F. (2025). Is Peace Education out of Style? The (Im)Possibilities of a Transformative Education. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101293