The Effect of Growth Mindset Interventions on Students’ Self-Regulated Use of Retrieval Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Retrieval Practice

1.2. Growth Mindset

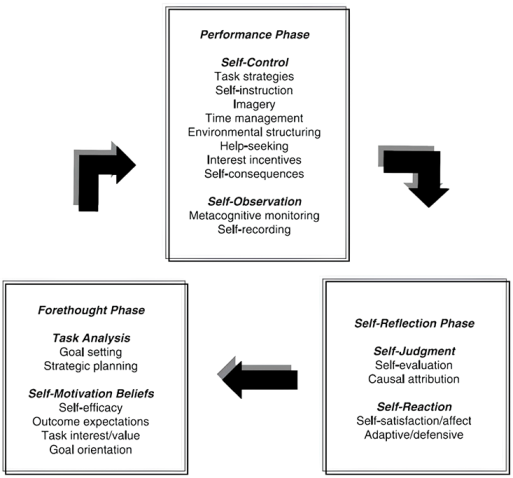

1.3. Cognitive Load

2. Current Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. The General Growth Mindset Intervention

3.2.2. The SRL Growth Mindset Intervention

3.2.3. The Neutral Intervention

3.2.4. Retrieval Practice Instruction

3.2.5. Learning Task

3.2.6. Cued-Recall Test

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. General and SRL Growth Mindset Beliefs

3.3.2. Retrieval Practice Decisions

3.3.3. Mental Effort

3.3.4. Immediate and Delayed Recall Performance

3.3.5. Retrieval Practice Beliefs

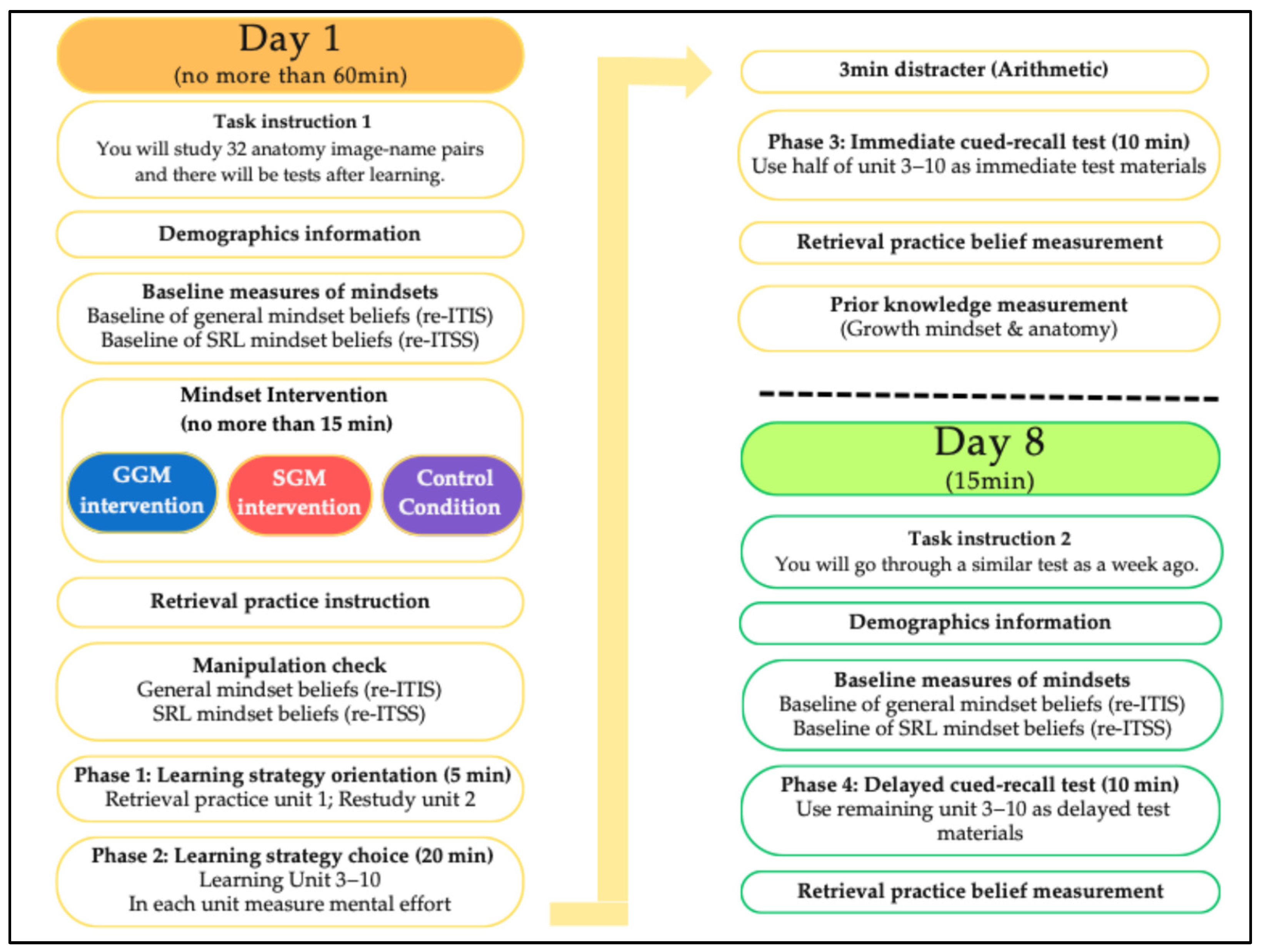

4. Procedure

5. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Growth Mindset Beliefs

6.2. Retrieval Practice

6.3. Perceived Mental Effort

6.4. Cued-Recall Performance

7. Discussion

8. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BOA | Bayesian one-way ANOVA |

| GGM | General Growth Mindset |

| Gain Score_GGM | Gain scores for general growth mindsets |

| Gain Score_SGM | Gain scores for SRL growth mindsets |

| NHST | The null hypothesis significance testing |

| re-ITIS | The revised Implicit Theories of Intelligence Scale |

| re-ITSS | The revised Implicit Theories of SRL Scale |

| SGM | SRL Growth Mindset |

| SRL | Self-regulated Learning |

Appendix A. Intervention Materials

Appendix A.1. General Growth Mindset Intervention

| Writing: |

| “Now, imagining a student who is struggling with his/her learning of anatomy in medical school, what would you like to say to him/her to overcome this challenge?” |

Appendix A.2. SRL Growth Mindset Intervention

| Writing: |

| “Now, imagining a student who is struggling with his/her learning of anatomy in medical school, what would you like to say to him/her to overcome this challenge?” |

Appendix A.3. Control Group Intervention

| Writing: |

| “Please write down a short summary about ‘The Neuron, Building Block of the Brain’” |

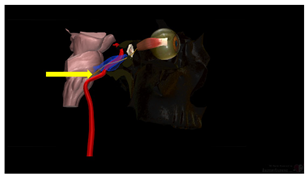

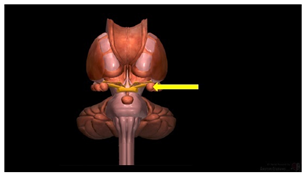

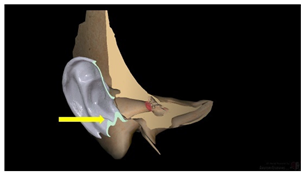

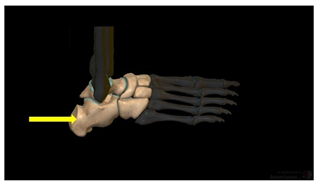

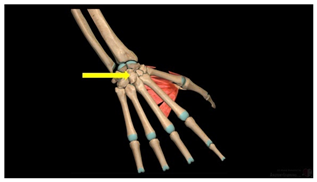

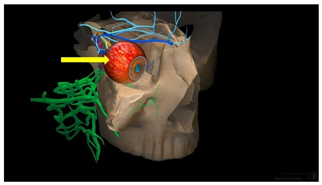

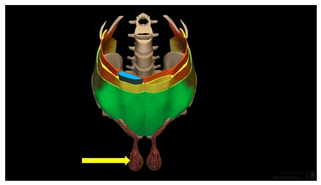

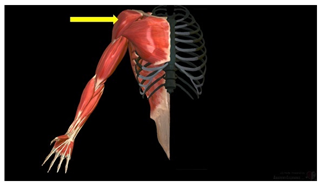

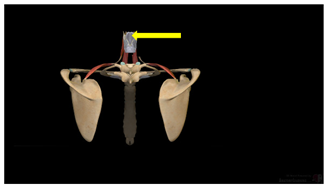

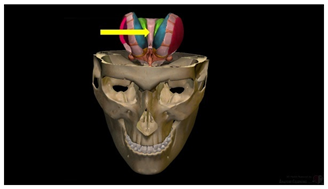

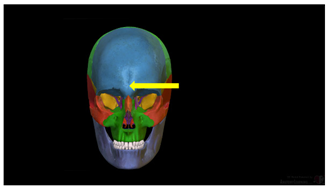

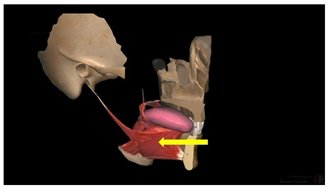

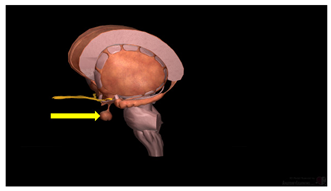

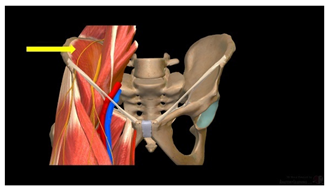

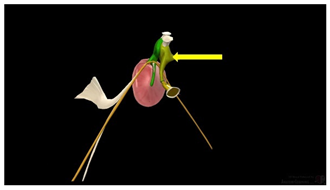

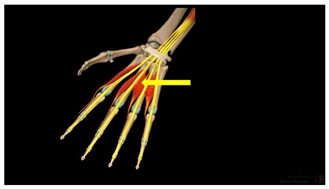

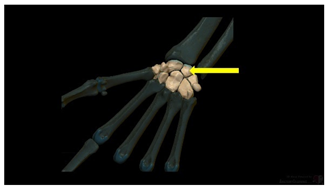

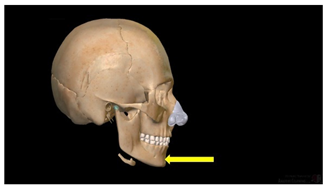

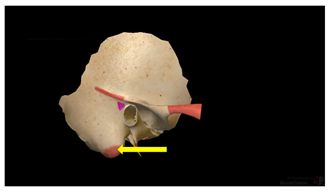

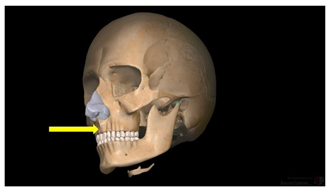

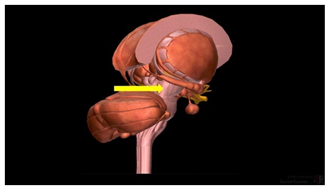

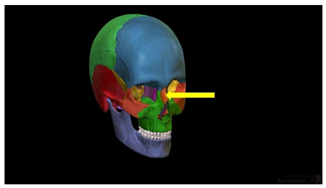

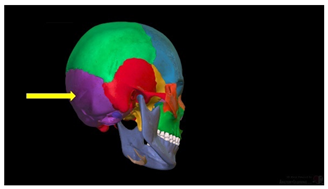

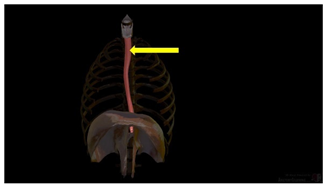

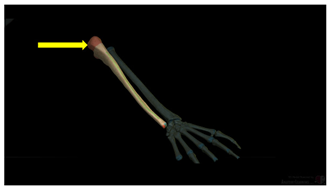

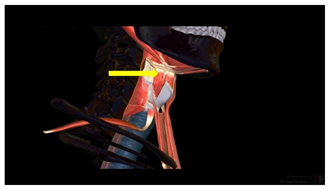

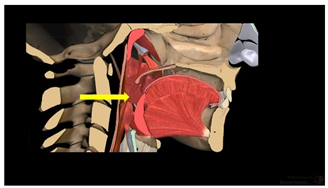

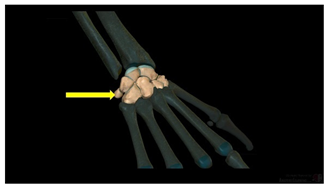

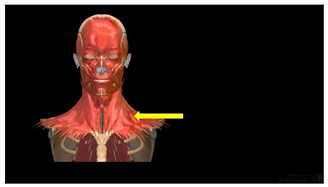

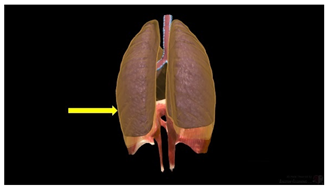

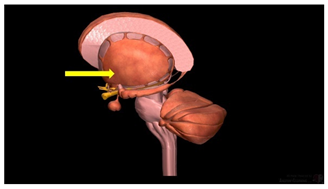

Appendix B. Learning Materials (Anatomy Image–Name Pairs)

| Image | Name |

| Abducens nerve |

| Amygdala |

| Antitragus |

| Brachialis muscle |

| Buccinator muscle |

| Calcaneum |

| Capitate bone |

| Choroid |

| Claustrum |

| Cornea |

| Cremaster |

| Deltoid |

| Dentine |

| Epiglottis |

| Femur |

| Fornix |

| Glabella |

| Hyoglossus muscle |

| Hypophysis |

| Iliacus |

| Incus |

| Lumbrical muscle |

| Lunate |

| Mandible |

| Mastoid |

| Maxilla |

| Midbrain |

| Nasal bone |

| Occipital bone |

| Oesophagus |

| Olecranon |

| Omohyoid |

| Oropharynx |

| Palatine bone |

| Patella |

| Piriformis |

| Pisiform bone |

| Platysma muscle |

| Pleura |

| Putamen |

Appendix C. Scales

Appendix C.1

- I don’t think I personally can do much to increase my intelligence.

- My intelligence is something about me that I personally can’t change very much.

- To be honest, I don’t think I can really change how intelligent I am.

- I can learn new things, but I don’t have the ability to change my basic intelligence.

- With enough time and effort, I think I could significantly improve my intelligence level.

- I believe I can always substantially improve on my intelligence.

- Regardless of my current intelligence level, I think I have the capacity to change it quite a bit.

- I believe I have the ability to change my basic intelligence level considerable over time.

- The items 1–4 measure the fixed mindset, we will reverse the scores of these four items during analyzation.

- The items 5–8 measure the growth mindset.

Appendix C.2

- I have a certain ability to self-regulate my learning and this ability can be changed.

- My ability of self-regulated learning can be improved by practice.

- How well I can self-regulate my learning is something that always stays the same.

- My successful academic performance at university does require competencies in SRL.

- Self-regulated learning is not a prerequisite for my successful study.

- In order to be successful in university studies, I must be very good in SRL.

- The items 1–3 measure the belief about the malleability of the SRL ability. The item 1 and 2 measure the growth mindset, item 3 measures the fixed growth mindset. We will reverse the score of the item 3 during analyzation.

- The items 4–6 measure the belief about the relevance of the SRL ability to the success in academia. The item 4 and 6 measure the growth mindset, item 5 measures the fixed mindset. We will reverse the score of the item 5 during analyzation.

Appendix C.3

| Measurement | Questions |

| Retrieval practice beliefs | “How effective is self-testing in helping you to memorize the anatomical image-name pairs from (1) extremely ineffective to (7) extremely effective?” |

| Retrieval practice decisions | “Now that you have studied this item twice, do you want to: A. restudy or B. self-test?” |

| Mental effort | “You studied four image-name pairs. How much mental effort did you invest from very, very little mental effort (1) to very, very much mental effort (9)?” |

References

- Adesope, O. O., Trevisan, D. A., & Sundararajan, N. (2017). Rethinking the use of tests: A meta-analysis of practice testing. Review of Educational Research, 87(3), 659–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P. K., Bain, P. M., & Chamberlain, R. W. (2012). The value of applied research: Retrieval practice improves classroom learning and recommendations from a teacher, a principal, and a scientist. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, R., & Karpicke, J. D. (2018). Improving self-regulated learning with a retrieval practice intervention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 24(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-regulated learning: Where we are today. International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology, 54(2), 199–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeren, M., Heijltjes, A., Verkoeijen, P., Smeets, G., & Arends, L. (2021). Supporting the self-regulated use of retrieval practice: A higher education classroom experiment. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 64, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., Billingsley, J., Banks, G. C., Knouse, L. E., Hoyt, C. L., Pollack, J. M., & Simon, S. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of growth mindset interventions: For whom, how, and why might such interventions work? Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 174–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., Hoyt, C. L., Russell, V. M., Lawson, B., Dweck, C. S., & Finkel, E. (2020). A growth mind-set intervention improves interest but not academic performance in the field of computer science. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(1), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., O’boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2007). Testing improves long-term retention in a simulated classroom setting. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4–5), 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. K. (2023). Encouraging students to use retrieval practice: A review of emerging research from five types of interventions. Educational Psychology Review, 35(4), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. K., & DeLosh, E. L. (2006). Impoverished cue support enhances subsequent retention: Support for the elaborative retrieval explanation of the testing effect. Memory & Cognition, 34(2), 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- De Castella, K., & Byrne, D. (2015). My intelligence may be more malleable than yours: The revised implicit theories of intelligence (self-theory) scale is a better predictor of achievement, motivation, and student disengagement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, K. J., Kester, L., & Kirschner, P. A. (2014). The testing effect for learning principles and procedures from texts. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(5), 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in The Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development. Psychological Review, 124(6), 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Master, A. (2012). Self-theories motivate self-regulated learning. In Motivation and self-regulated learning (pp. 31–51). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Parents’ views of failure predict children’s fixed and growth intelligence mind-sets. Psychological Science, 27(6), 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, M. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2012). Study strategies of college students: Are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(1), 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, S., & Karlen, Y. (2021). Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students’ achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), 972–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A. J., & Buro, K. (2009). Implicit beliefs, achievement goals, and procrastination: A mediational analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(1), 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L., de Bruin, A. B., Donkers, J., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2021). Does individual performance feedback increase the use of retrieval practice? Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1835–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, Y., & Compagnoni, M. (2017). Implicit theory of writing ability: Relationship to metacognitive strategy knowledge and strategy use in academic writing. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 16(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Karlen, Y., & Hertel, S. (Eds.). (2021). The power of implicit theories for learning in different educational contexts. Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Karlen, Y., Hirt, C. N., Liska, A., & Stebner, F. (2021). Mindsets and self-concepts about self-regulated learning: Their relationships with emotions, strategy knowledge, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 661142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D. (2017). Retrieval-based learning: A decade of progress. Grantee Submission. [Google Scholar]

- Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(4), 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornell, N., & Son, L. K. (2009). Learners’ choices and beliefs about self-testing. Memory, 17(5), 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macnamara, B. N., & Burgoyne, A. P. (2023). Do growth mindset interventions impact students’ academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis with recommendations for best practices. Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 133–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, M. A., Agarwal, P. K., Huelser, B. J., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2011). Test-enhanced learning in a middle school science classroom: The effects of quiz frequency and placement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(2), 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J. S., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y. H. (2011). Mind your errors: Evidence for a neural mechanism linking growth mind-set to adaptive posterror adjustments. Psychological Science, 22(12), 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, E., Haimovitz, K., Ballweber, C., Dweck, C., & Popović, Z. (2014, April 26–May 1). Brain points: A growth mindset incentive structure boosts persistence in an educational game. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3339–3348), Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2020). Cognitive-load theory: Methods to manage working memory load in the learning of complex tasks. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(4), 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F. G. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: A cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Puustinen, M., & Pulkkinen, L. (2001). Models of self-regulated learning: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 45(3), 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyc, M. A., & Rawson, K. A. (2009). Testing the retrieval effort hypothesis: Does greater difficulty correctly recalling information lead to higher levels of memory? Journal of Memory and Language, 60(4), 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, H. L., III, & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2006a). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2006b). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(3), 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, C. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1432–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T., & McCrudden, M. T. (2020). Retrieval practice and retention of course content in a middle school science classroom. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(6), 1510–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. J., & Ghinea, G. (2013). On the domain-specificity of mindsets: The relationship between aptitude beliefs and programming practice. IEEE Transactions on Education, 57(3), 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Kim, S. I., & Bong, M. (2020). Controllability attribution as a mediator in the effect of mindset on achievement goal adoption following failure. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storm, B. C., Bjork, R. A., & Storm, J. C. (2010). Optimizing retrieval as a learning event: When and why expanding retrieval practice enhances long-term retention. Memory & Cognition, 38, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J., & Paas, F. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10, 251–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E. J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., Love, J., Selker, R., Gronau, Q. F., Šmíra, M., Epskamp, S., Matzke, D., Rouder, J. N., & Morey, R. D. (2018). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 279–306). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J., Baars, M., Davis, D., Van Der Zee, T., Houben, G. J., & Paas, F. (2019). Supporting self-regulated learning in online learning environments and MOOCs: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 35(4–5), 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. M., Koorn, P., de Koning, B., Skuballa, I. T., Lin, L., Henderikx, M., Marsh, H. W., Sweller, J., & Paas, F. (2021). A growth mindset lowers perceived cognitive load and improves learning: Integrating motivation to cognitive load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(6), 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. M., Leferink, L., & Wijnia, L. (2025). A review of the relationship between student growth mindset and self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1539639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, V. X., & Schuetze, B. A. (2023). What is meant by “growth mindset”? Current theory, measurement practices, and empirical results leave much open to interpretation: Commentary on Macnamara and Burgoyne (2023) and Burnette et al. (2023). Psychological Bulletin, 149(3–4), 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., … Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). From cognitive modeling to self-regulation: A social cognitive career path. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Moylan, A. R. (2009). Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 299–315). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Characteristics | GGM Condition | SGM Condition | Control Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 47 | 81.03 | 52 | 81.25 | 46 | 82.14 |

| Male | 10 | 17.24 | 11 | 17.19 | 8 | 12.5 |

| Third gender | 1 | 1.72 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3.57 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 19.93 | 2.67 | 20.02 | 1.80 | 20.09 | 2.28 |

| Prior-Knowledge a | ||||||

| Anatomy * | 1.95 | 0.61 | 2.02 | 0.60 | 2.32 | 0.58 |

| Growth mindset | 2.64 | 1.14 | 2.66 | 1.04 | 2.66 | 1.07 |

| English Level | 4.36 | 0.81 | 4.13 | 0.86 | 4.16 | 0.65 |

| Dependent Variables | GGM Condition | SGM Condition | Control Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Growth mindset baseline | ||||||

| General growth mindset | 4.43 | 0.85 | 4.24 | 1.05 | 4.37 | 0.89 |

| SRL growth mindset | 4.69 | 0.52 | 4.68 | 0.62 | 4.78 | 0.44 |

| Gain score | ||||||

| General growth mindset | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.33 |

| SRL growth mindset | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.49 | −0.01 | 0.37 |

| Delayed gain score | ||||||

| General growth mindset | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.59 | −0.15 | 0.45 |

| SRL growth mindset | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.58 | −0.14 | 0.37 |

| Retrieval practice decisions | 6.40 | 1.89 | 6.11 | 1.86 | 6.36 | 1.96 |

| Mental effort | 6.62 | 0.97 | 6.71 | 1.17 | 6.60 | 1.08 |

| Learning Performance | ||||||

| Immediate cued-recall | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.17 |

| Delayed cued-recall | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Retrieval practice beliefs | ||||||

| Day 1 | 4.17 | 1.56 | 4.47 | 1.14 | 4.14 | 1.27 |

| Day 8 | 2.91 | 1.59 | 2.92 | 1.29 | 2.73 | 1.37 |

| Dependent Variables | F(2, 175) | p | ηp2 | BF10 (Model) | Group Differences (Post Hoc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gain score | |||||

| General growth mindset | 18.27 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 2.04 × 105 | GGM > SGM (p = 0.012, BF10 = 9.61); SGM > Ctrl (p = 0.002, BF10 = 27.64); GGM > Ctrl (BF10 = 4.81 × 105) |

| SRL growth mindset | 5.32 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 5.58 | SGM > GGM (p = 0.03, BF10 = 1.18); SGM > Ctrl (p = 0.002, BF10 = 31.55); GGM ≈ Ctrl (BF10 = 0.31) |

| Delayed gain score | |||||

| General growth mindset | 15.81 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 2.96 × 104 | GGM > SGM (p = 0.004, BF10 = 21.92); GGM > Ctrl (p < 0.001, BF10 = 7.82 × 104); SGM > Ctrl (p = 0.05, BF10 = 2.39) |

| SRL growth mindset | 3.88 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.49 | GGM, SGM > Ctrl (BF10 = 3.09; 3.66); GGM ≈ SGM (BF10 = 0.20) |

| Retrieval practice decisions | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.005 | 0.08 | No significant group differences; BF strongly supports null |

| Retrieval practice beliefs | |||||

| Day 1 | 1.13 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.15 | No group differences; SGM ≈ GGM (BF10 = 0.37); SGM ≈ Ctrl (BF10 = 0.52); GGM ≈ Ctrl (BF10 = 0.20) |

| Day 8 | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.004 | 0.08 | No group differences; all BFs < 0.30 favoring null |

| Gain Score | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.005 | 0.09 | No group differences; all BFs < 0.3 favoring null |

| Mental effort | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.002 | 0.07 | No group differences; all BFs < 0.25 favoring null |

| Learning Performance | |||||

| Immediate cued-recall | 2.89 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.69 | SGM > GGM (p = 0.05, BF10 = 2.72); others non-significant (BFs < 0.5) |

| Delayed cued-recall | 1.03 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.14 | No group differences; performance uniformly low; all BFs < 0.6 favoring null |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Baars, M.; Xu, K.M.; Paas, F. The Effect of Growth Mindset Interventions on Students’ Self-Regulated Use of Retrieval Practice. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101267

Xiao J, Baars M, Xu KM, Paas F. The Effect of Growth Mindset Interventions on Students’ Self-Regulated Use of Retrieval Practice. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101267

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jingshu, Martine Baars, Kate Man Xu, and Fred Paas. 2025. "The Effect of Growth Mindset Interventions on Students’ Self-Regulated Use of Retrieval Practice" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101267

APA StyleXiao, J., Baars, M., Xu, K. M., & Paas, F. (2025). The Effect of Growth Mindset Interventions on Students’ Self-Regulated Use of Retrieval Practice. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101267