Effects of a Teacher-Led Intervention Fostering Self-Regulated Learning and Reading among 5th and 6th Graders—Treatment Integrity Matters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

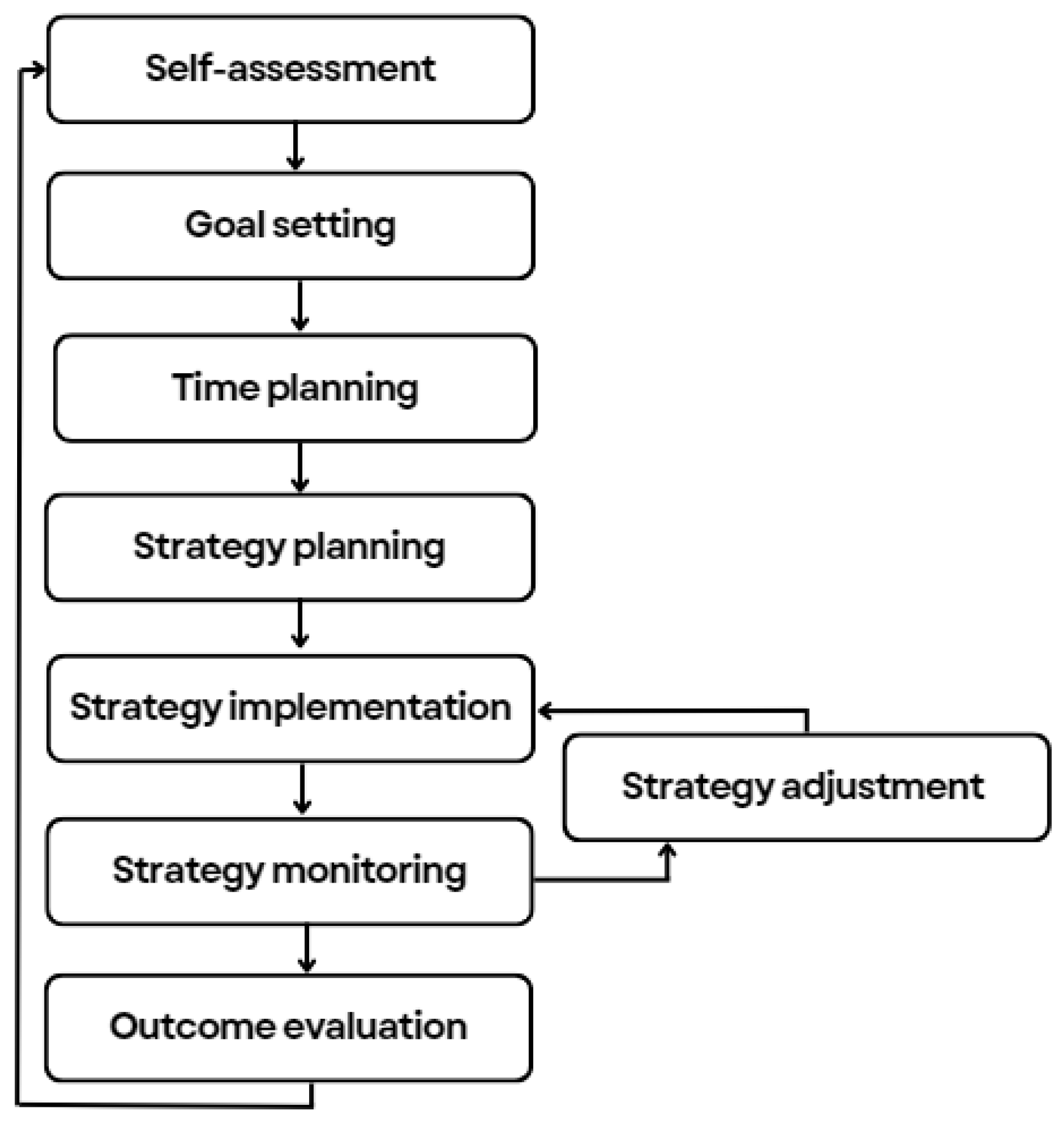

2.1. The Process of Self-Regulated Learning

2.2. Promoting SRL—General Considerations

2.3. Effectiveness of Previous Intervention Studies Promoting SRL within Reading Tasks at Primary School

2.4. Conducting Intervention Studies: Relevance of Treatment Integrity

3. The Current Study

- (1)

- Did the intervention significantly increase the reported SRL activities of the experimental group in comparison with the control group in the medium (post-test) and long term (post-test) (while controlling for gender, cognitive ability, first language, parental educational level, and participation in parental training)?

- (2)

- Did the intervention significantly increase reading comprehension in the experimental group in comparison with the control group in the medium and long term (while controlling for gender, cognitive ability, first language, parental educational level, and participation in parental training)?

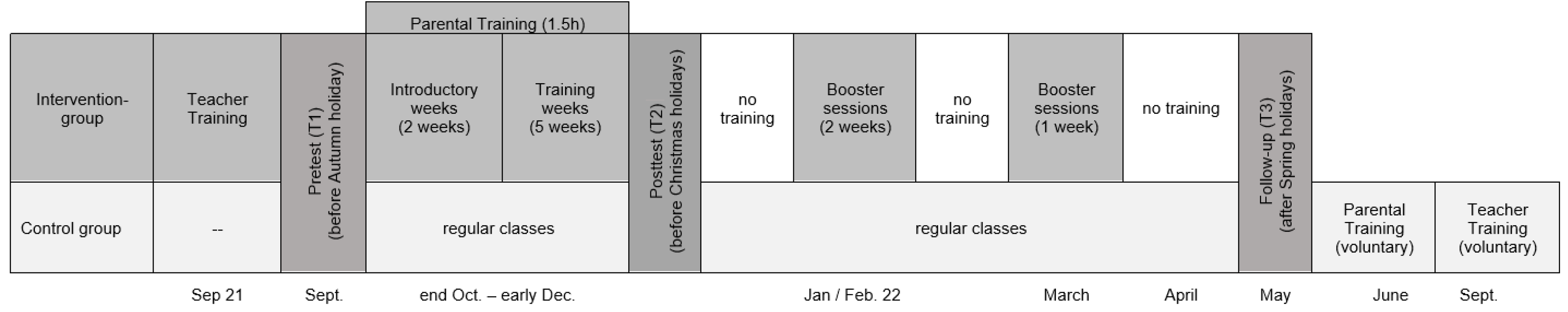

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Recruitment

4.2. Participants

5. Intervention Program

5.1. Teacher Training

5.2. Parental Training

5.3. Students’ Training

5.4. Treatment Integrity

6. Instruments

6.1. Self-Regulated Learning

6.2. Reading Comprehension

6.3. Control Variables

6.3.1. Cognitive Abilities

6.3.2. First Language

6.3.3. Parental Educational Level

6.3.4. Participation in Parental Training

6.4. Treatment Integrity

7. Statistical Analyses

8. Results

8.1. Descriptives, Zero-Order Correlations, and Group Differences

8.2. Intervention Effects on Dependent Variables

8.2.1. Results for SRL Activities

8.2.2. Results for Reading Comprehension

8.2.3. Understanding the Effects: Considering Treatment Integrity Variables

8.2.4. Predicting SRL Activities with Treatment Integrity Variables

8.2.5. Predicting Reading Comprehension with Treatment Integrity Variables

9. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | Model Description | χ2 | df | MDΔχ2 | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | ΔTLI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPa | Configural model | 1839.463 * | 868 | - | 0.947 | - | 0.942 | - | 0.038 | - |

| MPb | First-order factor loadings | 1857.721 * | 882 | 27.329 | 0.947 | 0.000 | 0.943 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

| MPc | Second-order factor loadings | 1875.031 * | 889 | 25.003 * | 0.946 | −0.001 | 0.943 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

| MPd | Thresholds of measured variables | 1886.077 * | 924 | 55.249 | 0.948 | 0.002 | 0.946 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.001 |

| MPe | Intercepts of first-order factors | 1928.489 * | 931 | 56.454 * | 0.946 | −0.002 | 0.945 | −0.001 | 0.038 | −0.001 |

| MPf | Disturbances of first-order factors | 1930.454 * | 953 | 69.424 * | 0.947 | 0.001 | 0.947 | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.001 |

| MPg | Disturbances of measured variables | 1948.825 * | 960 | 31.368 * | 0.946 | −0.001 | 0.947 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.000 |

| Model | Model Description | χ2 | df | MDΔχ2 | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | ΔTLI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFa | Configural model | 1837.910 * | 868 | - | 0.943 | - | 0.938 | - | 0.039 | - |

| MFb | First-order factor loadings | 1891.956 * | 882 | 36.205 * | 0.943 | 0.000 | 0.938 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.000 |

| MFc | Second-order factor loadings | 1902.617 * | 889 | 16.697 | 0.942 | −0.001 | 0.939 | −0.001 | 0.039 | 0.000 |

| MFd | Thresholds of measured variables | 1936.116 * | 924 | 74.095 * | 0.942 | 0.000 | 0.941 | −0.002 | 0.038 | 0.001 |

| MFe | Intercepts of first-order factors | 1960.111 * | 931 | 34.739 * | 0.941 | −0.001 | 0.941 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

| MFf | Disturbances of first-order factors | 1962.980 * | 953 | 70.834 * | 0.943 | 0.002 | 0.943 | −0.002 | 0.037 | 0.001 |

| MFg | Disturbances of measured variables | 1997.701 * | 960 | 42.316 * | 0.941 | −0.002 | 0.942 | 0.001 | 0.038 | −0.001 |

References

- OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030. OECD Learning Compass 2030. A Series of Concept Notes. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Sitzmann, T.; Ely, K. A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: What we know and where we need to go. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.R. The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 402–451. [Google Scholar]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G. Teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes—Insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacognition Learn. 2018, 13, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistner, S.; Rakoczy, K.; Otto, B.; Klieme, E.; Büttner, G. Teaching learning strategies. The role of instructional context and teacher beliefs. J. Educ. Res. Online 2015, 7, 176–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirweg, S.; De Smul, M.; Merchie, E.; Devos, G.; Van Keer, H. The long road from teacher professional development to student improvement: A school-wide professionalization on self-regulated learning in primary education. Res. Pap. Educ. 2021, 37, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, H.; Sontag, C.; Ziegler, A. Impact of a teacher-led intervention on preference for self-regulated learning, finding main ideas in expository texts, and reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benick, M.; Dörrenbächer-Ulrich, L.; Weißenfels, M.; Perels, F. Fostering SRL in primary school students: Can an additional teacher training enhance the intervention effects? Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2021, 20, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G.; Langfeldt, H.-P. How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively? A meta-analysis on self-regulation training programmes. Educ. Res. Rev. 2008, 3, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelt, C.; Schneider, W. Cross-country generalizability of the role of metacognitive knowledge for students’ strategy use and reading competence. Teach. Coll. Rec. Voice Scholarsh. Educ. 2015, 117, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, E.; Gillies, R.M. Teachers and the Teaching of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL): The Emergence of an Integrative, Ecological Model of SRL-in-Context. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žerak, U.; Juriševič, M.; Pečjak, S. Parenting and teaching styles in relation to student characteristics and self-regulated learning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 39, 1327–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, B. SELVES Schüler-, Eltern- und Lehrertrainings zur Vermittlung Effektiver Selbstregulation. [SELVES Student, Parent, and Teacher Training to Promote Effective Self-Regulation]; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stöger, H.; Ziegler, A. Trainingshandbuch Selbstreguliertes Lernen II. Grundlegende Textverständnisstrategien für Schüler der 4. Bis 8. Jahrgangsstufe. [Training Manual for Self-Regulated Learning II. Basic Text Comprehension Strategies for Students in Years 4 to 8]; Pabst: Lengerich, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, H.J. Domain-specific self-regulated learning interventions for elementary school students. Learn. Instr. 2023, 88, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; El-Bassel, N.; Ghesquiere, A.; Baldwin, S.; Gillies, J.; Ngeow, E. Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Panadero, E. A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmann, M.; Perels, F.; Otto, B.; Schnick-Vollmer, K.; Schmitz, B. Selbstregulation und selbstreguliertes Lernen [self-regulation and self-regulated learning]. In Einführung in Die Pädagogische Psychologie [Introduction into Pedagogical Psychology], 2nd ed.; Wild, E., Möller, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bong, M. Between-and within-domain relations of academic motivation among middle and high school students: Self-efficacy, task value, and achievement goals. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M. Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learn. Instr. 1997, 7, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevelde, S.; Van Keer, H.; Rosseel, Y. Measuring the complexity of upper primary school children’s self-regulated learning: A multi-component approach. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenman, M.V.J.; Van Hout-Wolters, B.H.A.M.; Afflerbach, P. Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacognition Learn. 2006, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souvignier, E.; Trenk-Hinterberger, I. Implementation eines Programms zur Förderung selbst-regulierten Lesens. Verbesserung der Nachhaltigkeit durch Auffrischungssitzungen. [Implementation of a Program to Foster Reading Competence: Improving Long-Term Effects by Using Booster-Sessions]. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2010, 24, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A.F.; Järvelä, S.; Miller, M. Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Schunk, D.H., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, R.E. Cooperative learning in elementary schools. Education 2015, 43, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.M.; Kuo, S.W. From Metacognition to Social Metacognition: Similarities, Differences, and Learning. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, H.; Donker, A.S.; Kostons, D.D.; van der Werf, G.P.C. Long-Term Effects of Metacognitive Strategy Instruction on Student Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 24, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellhäuser, H.; Liborius, P.; Schmitz, B. Fostering self-regulated learning in online environments: Positive effects of a web-based training with peer feedback on learning behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 813381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Boom, G.; Paas, F.; van Merriënboer, J.J. Effects of elicited reflections combined with tutor or peer feedback on self-regulated learning and learning outcomes. Learn. Instr. 2007, 17, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, N.; Spörer, N.; Völlinger, V.A.; Brunstein, J.C. Peer feedback mediates the impact of self-regulation procedures on strategy use and reading comprehension in reciprocal teaching groups. Instr. Sci. 2017, 45, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, R.; Boud, D. Researching feedback dialogue: An interactional analysis approach. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2015, 42, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N.; Littleton, K. Dialogue and the Development of Children’s Thinking: A Sociocultural Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pino-Pasternak, D.; Basilio, M.; Whitebread, D. Interventions and classroom contexts that promote self-regulated learning: Two intervention studies in United Kingdom primary classrooms. Psykhe 2014, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Pasternak, D.; Whitebread, D. The role of parenting in children’s self-regulated learning. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, I.; Kallia, E. The role of parents and teachers in fostering children’s self-regulated learning skills. In Trends and Prospects in Metacognition Research across the Life Span; Moraitou, D., Metallidou, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagais, R.; Pati, D. Associations between the home physical environment and child self-regulation: A conceptual exploration. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.C.; Tuero, E.; Fernández, E.; Añón, F.J.; Manalo, E.; Rosário, P. Effect of an intervention in self-regulation strategies on academic achievement in elementary school: A study of the mediating effect of self-regulatory activity. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2022, 27, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. Facilitating elaborative learning through guided student-generated questioning. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 27, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.H. Teaching students who struggle with learning to think before, while, and after reading: Effects of self-regulated strategy development instruction. Read. Writ. Q. 2013, 29, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risko, V.J.; Walker-Dalhouse, D.; Bridges, E.S.; Wilson, A. Drawing on text features for reading comprehension and composing. Read. Teach. 2011, 64, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souvignier, E.; Mokhlesgerami, J. Using self-regulation as a framework for implementing strategy-instruction to foster reading comprehension. Learn. Instr. 2006, 16, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitendra, A.K.; Hoppes, M.K.; Xin, Y.P. Enhancing main idea comprehension for students with learning problems: The role of a summarization strategy and self-monitoring instruction. J. Spec. Educ. 2000, 34, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E.; Lake, C.; Chambers, B.; Cheung, A.; Davis, S. Effective reading programs for the elementary grades: A best-evidence synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 1391–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.C.; Malone, L.D.; Kameenui, E.J. Effects of graphic organizer instruction on fifth-grade students. J. Educ. Res. 1995, 89, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.-H.; Vaughn, S.; Wanzek, J.; Wei, S. Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD: A synthesis of research. J. Learn. Disabil. 2004, 37, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelt, C.; Schiefele, U.; Schneider, W.; Stanat, P. Leseleistungen deutscher Schülerinnen und Schüler im internationalen Vergleich (PISA): Ergebnisse und Erklärungsansätze. [Reading performance of German pupils in international comparison (PISA): Results and explanatory approaches]. Z. Für Erzieh. 2002, 5, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrberg, E.; Rosén, M. Direct and indirect effects of parents’ education on reading achievement among third graders in Sweden. British Journal of Educational Psychology 2009, 79, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, B.D.; Southam-Gerow, M.A.; Weisz, J.R. Conceptual and methodological issues in treatment integrity measurement. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 38, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A. The importance of doing well in whatever you do: A commentary on the special section, “Implementation research in early childhood education”. Early Child. Res. Q. 2010, 25, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K.S.; McLeod, B.D.; Conroy, M.A.; Mccormick, N. Developing treatment integrity measures for teacher-delivered interventions: Progress, recommendations and Future Directions. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 14, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.N.; Kupersmidt, J.B.; Voegler-Lee, M.E.; Arnold, D.; Willoughby, M.T. Predicting teacher participation in a classroom-based, integrated preventive intervention for preschoolers. Early Child. Res. Q. 2010, 25, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, P.; Symons, F. Observational Measurement of Behavior; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald, S.K. It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s… fidelity measurement in the real world. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2011, 18, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, C.; Brandt, W.C. Implementation Fidelity in Education Research: Designer and Evaluator Considerations, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanetti, L.M.H.; Charbonneau, S.; Knight, A.; Cochrane, W.S.; Kulcyk, M.C.M.; Kraus, K.E. Treatment fidelity reporting in intervention outcome studies in the school psychology literature from 2009 to 2016. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 901–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limόn, M.; Mason, L. (Eds.) Reconsidering Conceptual Change: Issues in Theory and Practice; Springer Dordrecht: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder, S.; Perels, F.; Schmitz, B. Selbstregulation und elterliche Hausaufgabenunterstützung. Die Evaluation eines Elterntrainings für Kinder der Sekundarstufe I. [Self-regulation and parental homework support. Evaluation of a parental training for children in lower secondary school]. Z. Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychol. 2004, 36, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, R.; Avraamidou, L.; Goedhart, M. Tell me a story: The use of narrative as a learning tool for natural selection. Educ. Media Int. 2017, 54, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörrenbächer, L.; Perels, F. More is more? Evaluation of interventions to foster self-regulated learning in college. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 78, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, J. Selbstreguliertes Lernen in der Grundschule. Die Bedeutung der Einstellungen von Lehrkräften und Eltern [Self-Regulated Learning in Primary School. The Relevance of Parents’ and Teachers’ Attitude]; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A.; Stöger, H.; Grassinger, R. Diagnostik selbstregulierten Lernens mit dem FSL-7. [Diagnostics of self-regulated learning with the FSL-7]. J. Für Begabtenförderung 2010, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Souvignier, E.; Trenk-Hinterberger, I.; Adem-Schwebe, S.; Gold, A. FLVT 5-6. Frankfurter Leseverständnistest für 5. Und 6. Klassen. [FLVT Frankfurt Reading Comprehension Test for 5th and 6th Graders]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.; Kintsch, W. Strategies of Discourse Comprehension; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.H. CFT 20-R. Grundintelligenztest Skala 2—Revision mit Wortschatztest und Zahlenfolgentest [CFT 20-R. Basic Intelligence Test Scale 2—Revision with Vocabulary Test and Number Sequence Test], 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus (Version 8); Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika 2010, 75, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Millsap, R.E.; West, S.G.; Tein, J.Y.; Tanaka, R.; Grimm, K.J. Testing measurement invariance in longitudinal data with ordered-categorical measures. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 486–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.F.; Sousa, K.H.; West, S.G. Teacher’s Corner: Testing Measurement Invariance of Second-Order Factor Models. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2005, 12, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Morin, A.J.S.; Schabram, K.; Wang, Z.N.; Chemolli, E.; Briand, M. Uncovering relations between leadership perceptions and motivation under different organizational contexts: A multilevel cross-lagged analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K.; Tofighi, D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, B.; Friese, M.; Hofmann, W.J.; Naumann, E. Quantitative Methoden. Band 1 [Quantitative Methods. Volume 1], 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, J.; Stoeger, H. How primary school teachers’ attitudes towards self-regulated learning (SRL) influence instructional behavior and training implementation in classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruce, R.; Bol, L. Teacher beliefs, knowledge, and practice of self-regulated learning. Metacognition Learn. 2015, 10, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelt, C. Wie prädiktiv sind retrospektive Selbstberichte über den Gebrauch von Lernstrategien für strategisches Lernen? [How predictive are retrospective self-reports on the use of learning strategies for strategic learning?]. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2000, 14, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.A. Interpreting effect sizes of education interventions. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, J.; Dunning, D. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakhill, J.; Cain, K.; Elbro, C. Understanding and Teaching Reading Comprehension: A Handbook; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J. A systematic review of teacher guidance during collaborative learning in primary and secondary education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, B.; Klug, J.; Schmidt, M. Assessing self-regulated learning using diary measures with university students. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Schunk, D.H., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.A.; Robertson, J.; Croker Costa, L.J. Assessing self-regulated learning using think aloud methods. In Handbook of Self-regulation of Learning and Performance; Schunk, D.H., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, T.J. Emergence of self-regulated learning microanalysis: Historical overview, essential features, and implications for research and practice. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Schunk, D.H., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, J.; Leutner, D. Self-Regulated Learning as a Competence. Z. Für Psychol./J. Psychol. 2008, 216, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanetti, L.M.H.; Kratochwill, T.R. Toward developing a science of treatment integrity: Introduction to the special series. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 38, 445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, A.; Dauber, S.; Lichvar, E.; Bobek, M.; Henderson, C.E. Validity of therapist self-report ratings of fidelity to evidence-based practices for adolescent behavior problems: Correspondence between therapists and observers. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 42, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Snow, P.; Serry, T.; Hammond, L. The role of background knowledge in reading comprehension: A critical review. Read. Psychol. 2021, 42, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | Experimental | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1. SRL pretest | 736 | 3.04 | 0.46 | 3.06 | 0.45 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2. SRL post-test | 721 | 3.09 | 0.44 | 3.08 | 0.45 | 0.67 ** | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. SRL follow-up | 728 | 3.01 | 0.47 | 3.02 | 0.46 | 0.59 ** | 0.72 ** | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. RC pre-test | 737 | 10.99 | 4.18 | 11.46 | 3.99 | −0.08 * | −0.08 * | −0.10 ** | -- | |||||||||

| 5. RC post-test | 717 | 12.13 | 3.69 | 12.65 | 3.35 | −0.11 ** | −0.05 | −0.09 * | 0.69 ** | -- | ||||||||

| 6. RC follow-up | 729 | 12.73 | 3.47 | 13.13 | 3.36 | −0.09 * | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.63 ** | 0.74 ** | -- | |||||||

| 7. Cognitive abilities | 734 | 35.46 | 6.62 | 36.04 | 6.22 | −0.13 * | −0.11 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.39 ** | -- | ||||||

| 8. Gender (1 = Female) | 757 | 125 | 48.6% | 268 | 53.6% | 0.08 * | 0.08 * | 0.09 * | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 * | 0.01 | -- | |||||

| 9. First LG (1 = Germ.) | 747 | 203 | 79.6% | 359 | 73.0% | −0.15 ** | −0.09 * | −0.16 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.01 | -- | ||||

| 10. PEL (1 = low) | 703 | 71 | 29.3% | 152 | 33.0% | 0.08 * | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.15 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.01 | −0.15 ** | -- | |||

| 11. PEL (1 = high) | 703 | 90 | 37.2% | 171 | 39.3% | −0.08 * | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.19 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.02 | 0.12 ** | −0.54 ** | -- | ||

| 12. Condition (1 = EC) | 757 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.07 * | 0.04 | 0.02 | -- | |

| 13. Particip. parents | 500 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | -- |

| Model 1 (Post-Test) | Model 2 (Follow-Up) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| SRL | ||||

| Intercept | −0.06 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.29 |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Pre-test SRL | 0.67 * | 0.03 | 0.58 * | 0.04 |

| Gender (1 = female) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| First language (1 = German) | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Cognitive abilities | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| PEL (1 = low) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| PEL (1 = high) | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Particip. parent. (1 = yes) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Condition (1 = Experimental) | −0.03 | 0.18 | −0.03 | 0.27 |

| R2 Level 1 | 0.45 | -- | 0.34 | -- |

| R2 Level 2 | 0.56 | -- | 0.30 | -- |

| Model 1 (Post-Test) | Model 2 (Follow-Up) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Reading comprehension | ||||

| Intercept | 6.79 | 1.20 | 7.07 | 3.26 |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Pre-test reading | 0.63 ** | 0.04 | 0.55 ** | 0.04 |

| Gender (1 = female) | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.10 ** | 0.03 |

| First language (1 = German) | 0.09 ** | 0.03 | 0.10 ** | 0.04 |

| Cognitive abilities | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.13 ** | 0.04 |

| PEL (low) | 0.10 ** | 0.04 | 0.13 ** | 0.04 |

| PEL (high) | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Particip. parent. | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Condition (1 = Experimental) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| R2 Level 1 | 0.47 | -- | 0.38 | -- |

| R2 Level 2 | 0.86 | -- | 0.84 | -- |

| SRL (Post-test) | SRL (Follow-Up) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Intercept | −0.04 (0.25) | −0.11 (0.24) | −0.05 (0.27) | −0.06 (0.26) | −0.11 (0.28) | −0.18 (0.30) | −0.12 (0.31) | −0.13 (0.31) |

| Level 1 | ||||||||

| Pre-test SRL | 0.66 ** (0.03) | 0.67 ** (0.03) | 0.67 ** (0.03) | 0.67 ** (0.03) | 0.57 ** (0.04) | 0.58 ** (0.04) | 0.57 ** (0.04) | 0.57 ** (0.04) |

| Gender (1 = female) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) |

| First language (1 = German) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | −0.09 * (0.04) | −0.08 * (0.04) | −0.09 * (0.04) | −0.09 * (0.04) |

| Cognitive abilities | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.03 (03) | 0.03 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) |

| PEL (low) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) |

| PEL (high) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) |

| Particip. Parent. | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) |

| Level 2 | ||||||||

| Adherence (CL) | 0.36 * (0.22) | - | - | - | 0.44 (0.38) | - | - | - |

| Adherence (QT) | - | 0.26 (0.21) | - | - | - | 0.16 (0.26) | - | - |

| Child resp. (SM) | - | - | 0.37 ** (0.19) | - | - | - | 0.48 (0.30) | - |

| Comp. Deliv. (CD) | - | - | - | −0.01 (0.16) | - | - | −0.05 (0.22) | |

| R2 Level 1 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| R2 Level 2 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schuler, N.; Villiger, C.; Krauß, E. Effects of a Teacher-Led Intervention Fostering Self-Regulated Learning and Reading among 5th and 6th Graders—Treatment Integrity Matters. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070778

Schuler N, Villiger C, Krauß E. Effects of a Teacher-Led Intervention Fostering Self-Regulated Learning and Reading among 5th and 6th Graders—Treatment Integrity Matters. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):778. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070778

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchuler, Nadine, Caroline Villiger, and Evelyn Krauß. 2024. "Effects of a Teacher-Led Intervention Fostering Self-Regulated Learning and Reading among 5th and 6th Graders—Treatment Integrity Matters" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070778

APA StyleSchuler, N., Villiger, C., & Krauß, E. (2024). Effects of a Teacher-Led Intervention Fostering Self-Regulated Learning and Reading among 5th and 6th Graders—Treatment Integrity Matters. Education Sciences, 14(7), 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070778