Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. School Education in India and the Role of EdTech

2.1. Background

2.2. Growth of EdTech in India

2.3. The EdTech Tulna Initiative

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Justice-as-Content: The Contextual Relevance of the EdTech Tulna Index

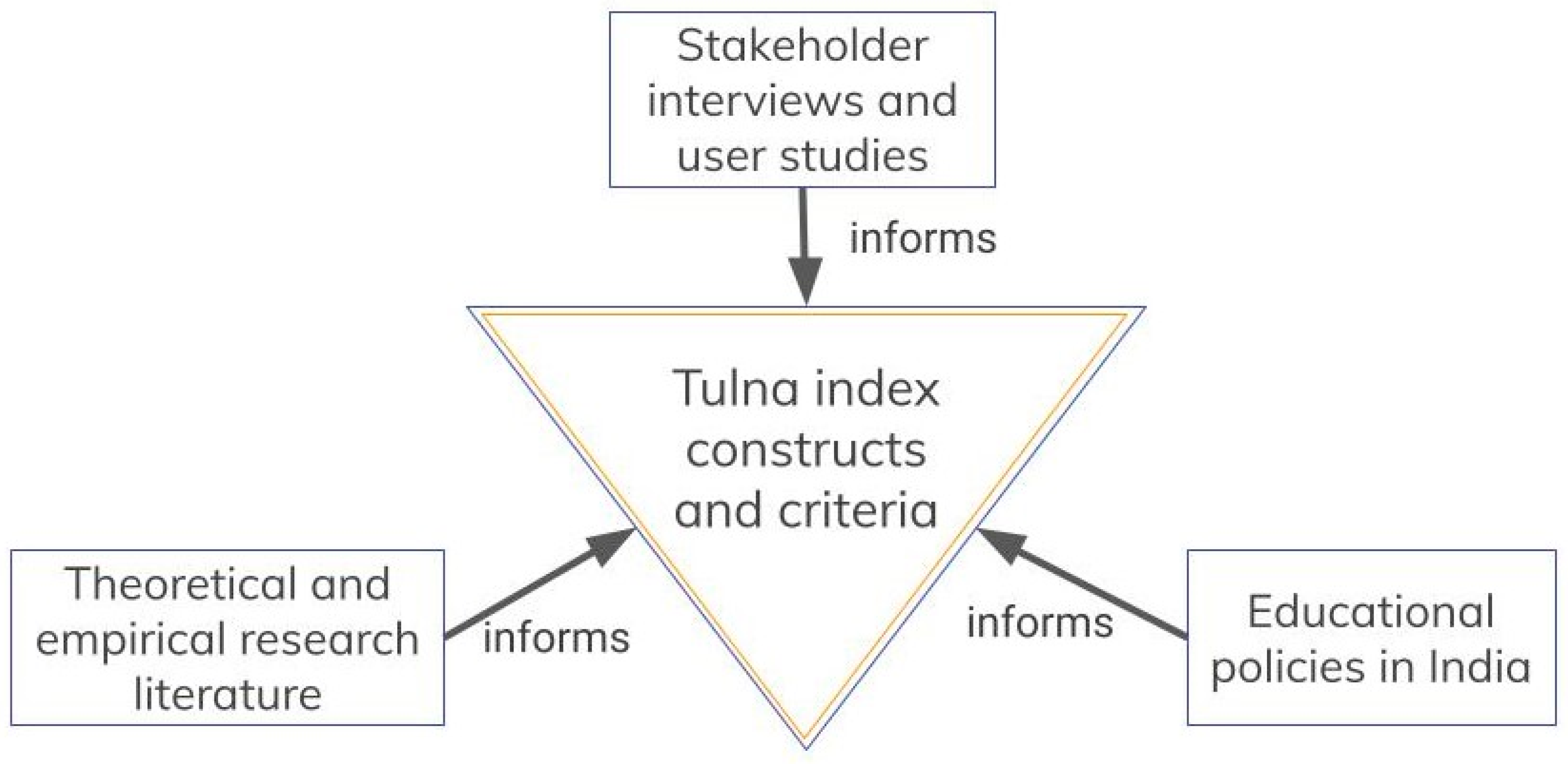

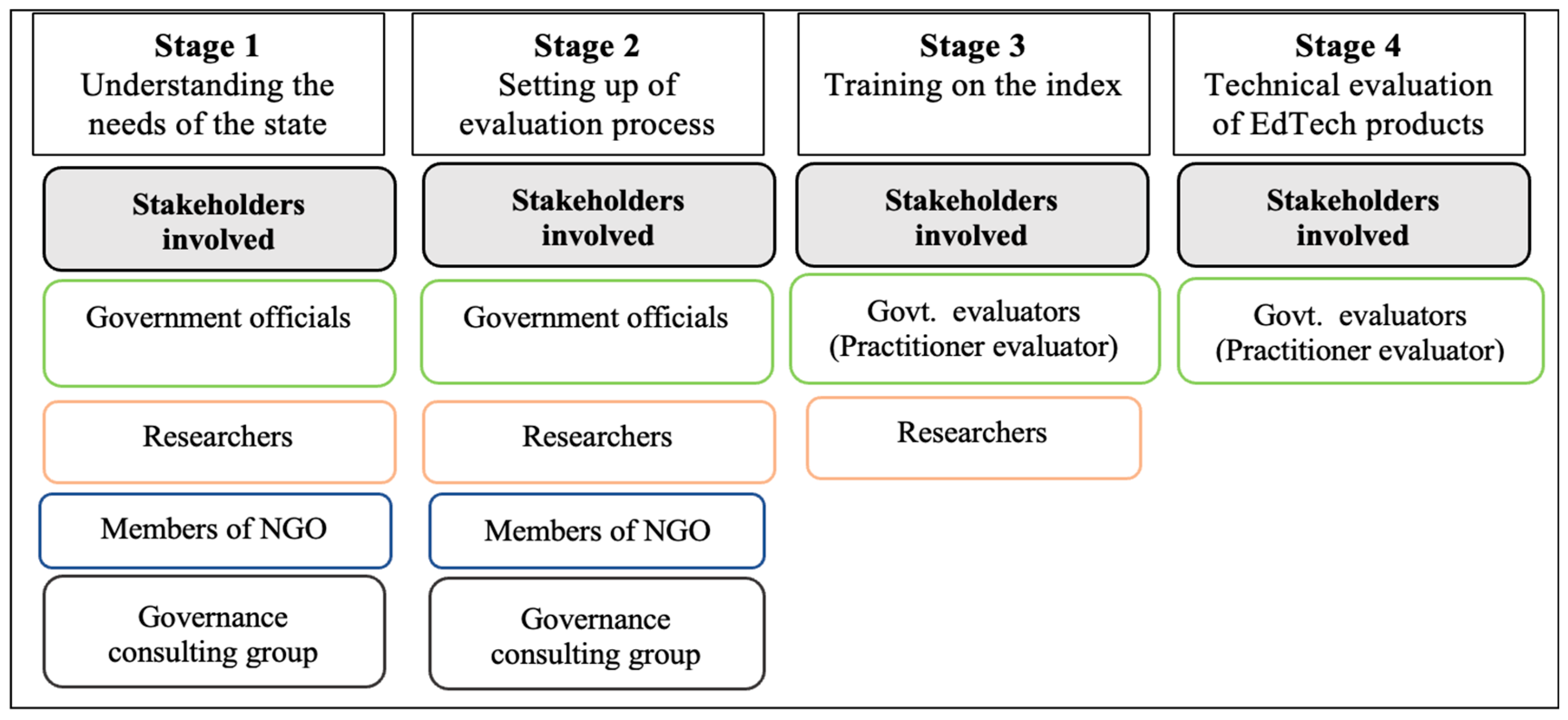

4.1. Tulna Index Design Process

4.2. Evaluation Parameters in Tulna Index

4.3. Analyzing Tulna Criteria Based on Justice-as-Content Framework

4.3.1. Content Quality Dimension

- Language comprehensibility: Use an easily understandable vocabulary and accent, keeping the intended learners in mind.This criterion checks whether the accent and the vocabulary used in the EdTech product are likely to be comprehended by the target learners. In our context, it checks for an Indian accent, even if the content is presented in English. A foreign-accented voice adds to the cognitive load of the learners [43]. A product is considered to be exemplary when the learners are likely to follow the accent without additional effort and the vocabulary is age-appropriate for the learners.

- Bilingual use: Use English technical terms as well as vernacular terms to present mathematical terms so that the learners become well-acquainted with the language of Mathematics.A dominant language of EdTech solutions in India is English. However, having all solutions in English is not an ideal case for the learners, many of whom do not speak English as a first or even a second language. The Tulna index encourages EdTech product designers to make their products available in multiple native languages, or at least to support the learners by providing scaffolds in the relevant native language. The presence of multiple languages in EdTech solutions would not only help learners stay engaged and obtain the support that they need but would also avoid their loss of identity from being exposed to content in a non-native language.

- Inclusivity in the representation of the learners: Address the diversity of target learners in terms of gender, race, socio-economic background, religion and appearance while creating content.EdTech solutions often are designed to include characters of fair skin and certain body types, which misrepresents the heterogeneity in Indian society. This criterion encourages the inclusion of individuals from different sub-sections of society in terms of body types, age, gender and ability, as well as clothes and accessories reflecting religion that an Indian learner is likely to observe around them. Products that are built for different country contexts and overrepresent fair-skinned people or support stereotypes are penalized under this criterion.

4.3.2. Pedagogical Alignment Dimension

- Content in context: Pay close attention to the learner’s context (who is learning) and location (where is the learning taking place) while designing pedagogy.The Tulna index checks whether the product design is rooted in the local and cultural context of the learners. This can be represented in terms of the choice of clothes, food, festivals or setting, to name a few. Products that are directly adopted from Western contexts or that are not designed for Indian learners are unlikely to accurately represent the needs of the intended learners and are penalized.

- Teacher support: Design supports for the teacher so that they know how to use the product meaningfully and can customize it to an extent in response to learners’ needs on the ground.Proficiency in the use of digital devices cannot be expected from all teachers, many of whom have been exposed to technology only in their adulthood. Thus, presenting an EdTech product without any support and guidance is unlikely to be successful in the classroom. This criterion checks whether the product design considers teachers as central agents of teaching. It focuses on the support provided to teachers on using the product effectively by integrating it with classroom teaching, and whether the teachers’ agency is valued.

- Opportunities for collaboration: Facilitate collaboration and scaffold learning via peer-to-peer interaction and feedback.Western-centric epistemological and pedagogical foundations in EdTech tend to prioritize individual learning paths and goals over emphasizing collective learning paths [44]. However, learning in small groups is more beneficial than individual learning [45] and Indian culture is deeply embedded in collectivism rather than individualism. Under this criterion, the products are penalized if they do not encourage group-based learning, especially the ones that are designed for classroom interventions.

5. Justice-as-Process: The Adoption Process of EdTech Tulna Index by an Indian State Government

5.1. Methods

5.1.1. Participants

5.1.2. Procedure

5.1.3. Data Collection and Analysis

5.2. Findings

5.2.1. Vignette 1: Multi-Voiced Approach to a Fair and Just Evaluation

There was considerable emphasis on involving teachers and bureaucrats in the state in the technical evaluation process.

Mr. A (GCG): “Quality of PAL [Personalized Adaptive Learning] was a critical thing in our mind. Of course, our understanding of how this is measured was very, very limited because we only knew certain private players who were making noise in the market at the time… we understood that there were some good players in the market who delivered PAL but we actually had no idea of how exactly this was measured and how quality of a PAL product was measured.”

Teacher S: “Personally it gave me a systematic way of judging something. Creating parameters, taking into all the aspects or factors of judging a thing, and doing it in a good way, you get an overall picture of the thing.”

5.2.2. Vignette 2: Empowering the Teachers with Decolonized Content and Training

Ms. B (GCG): “The role that Tulna played was to build the capacity of multiple stakeholders, all who are part of this decision-making process, at various stages. It builds the capacity and understanding of what good can look like around software and their confidence to make high stakes decisions…build capacity of multiple stakeholders.”

Ms. AK (NGO): “…one point of difficulty was… understanding the language of the framework itself…”

Ms. R (NGO): “The idea was the evaluation team would do the heavy lifting of all of these evaluations, analysis and all of that. And the high-powered committee would take the final call. Which is basically a very rigorous process. It allows stakeholders from teachers to senior bureaucrats in the states to get involved and it does it in a way that the louder voice, the more powerful voice is not of state or not amplified because of their position. Rather, everyone gets an equal voice in the process at some stage, right, and gets aggregated as you move forward.”

Teacher S: “Yes Now I am evaluating my own teaching and try to find out the points where I need improvement.”

Teacher P: “Earlier I used to focus only on content delivery but after training, I came to know about various pedagogical aspects which imparts an important role on learners’ ability.”

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Technology in Education: A tool on whose terms? In Global Education Monitoring Report 2023; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.; Johnson, D.; Somanchi, A.; Barton, H.; Joshi, R.; Seth, M.; Shotland, M. The EdTech Lab Series: Insights from Rapid Evaluations of EdTech Products; Central Square Foundation: Delhi, India, 2019; Available online: https://centralsquarefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/EdTech%20Lab%20Report_November%202019.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- ASER Centre. Annual Status of Education Report (Rural). 2022. Available online: http://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202022%20report%20pdfs/All%20India%20documents/aserreport2022.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- ASER 2022 National Findings. 2022. Available online: https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202022%20report%20pdfs/All%20India%20documents/aser2022nationalfindings.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Shah, M.; Steinberg, B. The Right to Education Act: Trends in enrollment, test scores, and school quality. AEA Pap. Proc. 2019, 109, 232–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, N.; Burch, P. Educational technology in India: The field and teacher’s sensemaking. Contemp. Educ. Dialogue 2019, 16, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Cole, S.; Duflo, E.; Lindon, L. Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 1235–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, K.; Singh, A.; Ganimian, A.J. Disrupting education? Experimental evidence on technology-aided instruction in India. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 1426–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Torppa, M.; Aro, M.; Richardson, U.; Lyytinen, H. Assessing the effectiveness of a game-based phonics intervention for first and second grade English language learners in India: A randomized controlled trial. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teräs, M.; Suoranta, J.; Teräs, H.; Curcher, M. Post-Covid-19 education and education technology ‘solutionism’: A seller’s market. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escueta, M.; Nickow, A.J.; Oreopoulos, P.; Quan, V. Upgrading Education with Technology: Insights from Experimental Research. J. Econ. Lit. 2020, 58, 897–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. How Haryana, UP & MP are Leading the Way in Regulating Edtech Content in Govt Schools. The Print. 2023. Available online: https://theprint.in/india/how-haryana-up-mp-are-leading-the-way-in-regulating-edtech-content-in-govt-schools/1450311/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Adam, T. Digital neocolonialism and massive open online courses (MOOCs): Colonial pasts and neoliberal futures. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, B. Decolonizing Technology: A Reading List. Beatrice Martini (Blog). 10 May 2017. Available online: https://beatricemartini.it/blog/decolonizing-technology-reading-list/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Tondeur, J.; van Braak, J.; Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T. Understanding the relationship between teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, V.S.; Deshmukh, K.S.; Shukla, A. Why does technology integration fail? Teacher beliefs and content developer assumptions in an Indian initiative. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2753–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EdTech Tulna, 2023. Available online: https://www.edtechtulna.org/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Bhattacharya, L.; Nandakumar, M.; Dasgupta, C.; Murthy, S. Adoption of quality EdTech products in India: A case study of government implementation towards a sustainable EdTech ecosystem. In Background Paper for UNESCO 2023 Report on Technology in Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386079/PDF/386079eng.pdf.multi (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Adam, T.; Moustafa, N.; Sarwar, M. Tackling Coloniality in EdTech: Making your Offering Inclusive and Socially Just, (Blog); 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T. Between Social Justice and Decolonisation: Exploring South African MOOC Designers’ Conceptualisations and Approaches to Addressing Injustices. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge. Am. J. Sociol. 1972, 78, 9–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHRD. Implementation of the ICT@schools Scheme: Model Bid Document. 2010. Available online: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/Model%20Bid%20Document%20for%20revised%20ICT%20Scheme.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Bhattacharya, L.; Chandrasekhar, S. India’s Search for Link Language and Progress towards Bilingualism, Working Paper Series, 2020, Number 15, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, India. Available online: http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/WP-2020-015.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Bharat Survey for EdTech (BaSE). Central Square Foundation. 2023. Available online: https://www.edtechbase.centralsquarefoundation.org/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Phillipson, R. Linguistic Imperialism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish, V. A peripherist view of English as a language of decolonization in post-colonial India. Lang. Policy 2005, 4, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Education Policy 2020, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. 2020. Available online: https://ncert.nic.in/pdf/nep//NEP_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Omidyar Network. Scaling Access and Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech. Omidyar Network. 2019. Available online: https://omidyar.com/scaling-access-impact-realizing-the-power-of-edtech/ (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Bahri, M.; Iyer, S. India Needs to Move from “Spending More” to “Spending Better” in Education. ORF. 2023. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/india-needs-to-move-from-spending-more-to-spending-better-in-education/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- CIET. ICT@Schools Scheme Implementation in the States: An Evaluation. 2014. Available online: https://ciet.nic.in/upload/ICTEvaluationReport.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Patel, A.; Dasgupta, C.; Murthy, S.; Dhanani, R. Co-Designing for a Healthy Edtech Ecosystem: Lessons from the Tulna Research-Practice Partnership in India; Rodrigo, M.M.T., Ed.; Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education: Taiwan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Howland, J.L.; Jonassen, D.H.; Marra, R.M. Meaningful Learning with Technology: Pearson New International Edition PDF eBook; Pearson Higher, Ed: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P. What is technological pedagogical content knowledge. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2009, 9, 60–70. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/29544/ (accessed on 24 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D.J.; Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, C.; Reiser, B.J.; Davis, E.A.; Krajcik, J.; Fretz, E.; Duncan, R.G.; Kyza, E.; Edelson, D.; Soloway, E. A scaffolding design framework for software to support science inquiry. In Scaffolding; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 337–386. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D. Preface. A Practical Reader in Universal Design for Learning; Harvard Education Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, M.; Bhattacharya, L.; Murthy, S. What Criteria are Important for Evaluating the Quality of English Language Learning Edtech Products? Evidence From Literature. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE) 2022, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28 November–2 December 2022; Available online: https://icce2022.apsce.net/uploads/P1_C6_86.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- National Council of Educational Research and Training. National Curriculum Framework 2005. New Delhi. 2005. Available online: https://ncert.nic.in/pdf/nc-framework/nf2005-english.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Soundararaj, G.; Badhe, V.; Ishika; Pawar, M.; Dasgupta, C.; Murthy, S. Unpacking contextual parameters influencing the quality of Personalized Adaptive Learning EdTech applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE) 2022, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28 November–2 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. Principles Based on Social Cues in Multimedia Learning: Personalization, Voice, Image, and Embodiment Principles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Volume 16, pp. 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T.; Binat, M. Decolonising Open Educational Resources (OER): Why The Focus on ‘Open’ and ‘Access’ Is Not Enough For The Edtech Revolution in EdTech Revolution, Education, General, Open Educational Resources, Tools, Open Development & Education. 2022. Available online: https://opendeved.net/2022/04/08/decolonising-open-educational-resources-oer-why-the-focus-on-open-and-access-is-not-enough-for-the-edtech-revolution/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Lou, Y.; Abrami, P.C.; d’Apollonia, S. Small group and individual learning with technology: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2001, 71, 449–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R.A. The effect of character similarity on children’s learning from fictional stories: The roles of race and gender. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2022, 214, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Chen, H.S.; Shadiev, R.; Huang, R.Y.M.; Chen, C.Y. Improving English as a foreign language writing in elementary schools using mobile devices in familiar situational contexts. CALL 2014, 27, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viennet, R.; Pont, B. Education Policy Implementation: A Literature Review and Proposed Framework; OECD Education Working Papers, no. 162; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhattacharya, L.; Nandakumar, M.; Dasgupta, C.; Murthy, S. Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050481

Bhattacharya L, Nandakumar M, Dasgupta C, Murthy S. Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(5):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050481

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhattacharya, Leena, Minu Nandakumar, Chandan Dasgupta, and Sahana Murthy. 2024. "Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem" Education Sciences 14, no. 5: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050481

APA StyleBhattacharya, L., Nandakumar, M., Dasgupta, C., & Murthy, S. (2024). Shaping the Discourse around Quality EdTech in India: Including Contextualized and Evidence-Based Solutions in the Ecosystem. Education Sciences, 14(5), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14050481