Abstract

This study focused on the connection between organisational school culture and the success of curriculum reform. Utilizing a sample of 348 teachers in 25 Swiss schools, we investigated how different school culture types correlate with teachers’ perceived success of the current process of implementing the “Media and Information Literacy” curriculum. We found that the school culture type Clan is the most dominant across the schools and found a negative connection between the school culture type Hierarchy and teachers’ perceived reform success. An exploratory cluster analysis was used to identify further profiles of school culture that were not based on the dominant culture but were determined based on the distribution of mean values. Two other profiles were identified in a further procedure: Collegial Associates and Competitive Organisations. These results thus fill a gap in the previous research on school culture that had particularly set out to identify the dominant school culture. Based on the results, we cannot only confirm the validity of the Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument for Swiss schools but also give indications as to which characteristics of school culture types are hindering the perceived success of curriculum reforms from the teachers’ points of view.

1. Introduction

School culture influences not only the learning and well-being of students and teachers but also how the school as an organisation responds to change [1]. School development is an ongoing task that schools must address because the environment, the generations of students, and the teachers change during their professional socialisation [2]. Thus, the sustainable change of schools is a complex undertaking that is shaped by the lived culture of the school, as well as by the regional and social framework conditions [3].

In the context of the ongoing digital transformation, digital and media-related content is increasingly integrated into school curricula. In Switzerland, authorities launched the implementation of a new curriculum, “Media and Information Literacy” (MIL), (In international discourse, the term “Media and Information Literacy” (MIL) is common [4]. The term “Media and ICT” (M&I), in Switzerland, refers to aspects of media and information technology education, as does the international term. For a better understanding, the international term will be used in the following) which stipulates that teachers must prepare their students for the digital age and workplace [5]. This curriculum reform introduced new demands on teachers in terms of learning content and teaching methods for digital literacy [6]. Existing research on the development of school culture can be described as rather stable [7,8]. However, teachers interpret reform projects against the background of the lived culture in their school [1,9]. Even though there is a growing body of research on school culture in the international context [3], so far there have been no studies investigating school culture in Swiss schools or specifically in the context of MIL.

The perception of school culture by teachers is examined, as it is seen as an important dimension of school development in the context of curriculum reform [10,11,12]. Moreover, the study explores the extent to which the current implementation of the MIL curriculum is being received by teachers and how this relates to the existing culture of their school. The results of the study aim to further establish the connection between school culture and school and curriculum development and to provide insights into the current school reform in Switzerland.

2. Theoretical Framework

The discussion about the concept of school culture has been an integral part of the educational discourse in German-speaking countries and internationally for over 30 years [1,13], in science and as a part of school practice [14]. Discussing school culture is challenging because there is no consensus on the definition of the concept [3,11,15].

Important theoretical approaches come from organisational research [16]. From this perspective, culture influences the way a school functions, how this is experienced by its members and how they interact with each other. In the US discourse schools were historically viewed as rational institutions with a clear outcome and accountability focus. Only in the 1980–1990′s was the notion of a more caring culture in schools proposed [17,18], which assumes that collaboration, relationships, and mutual support might be more important for student learning than the strict regulations of the bureaucratic national testing schemes [1].

In this paper, school culture is discussed according to the organisational psychology concept of organisational culture and is distinguished from other areas, such as learning culture or educational culture (e.g., [19,20,21]). It directly targets the organisational structures, processes, and attitudes of teachers in schools. The culture of a school is a collective attitude, but there can also be different, potentially conflicting subcultures [3].

According to Nerdinger et al. [22], organisations are social systems per se in which people work together over a long period. The organisation-specific norms and values regulate behaviour and ensure that employees are integrated into the organisation. Employees must adapt to the social practices practiced there and explore the possibility of meaningful behaviour [23]. Organisational culture thus represents the entire system of shared values and norms that defines interactions with organisational members and external parties [24]. It determines modes of action and behaviour [25], as well as strategies, goals, and functions of the organisation [26]. Following Luhmann [27], schools can be understood as organisations whose primary task is to plan social learning situations and to provide learning opportunities. Therefore, how teachers and principals design and live their culture may influence the quality of instruction, teacher collegiality, and student learning [3].

For this paper, we used a definition of school culture based on van Ackeren et al. [28], Esslinger-Hinz [29], and Schein [30]: school culture can be described as the interplay of applicable conscious and subconscious norms and values and the behaviour of all school stakeholders. Each teacher in a school has their individual perception of culture, shaped by their experiences and beliefs. Yet, we also assume that there is one view of culture that is dominant in a school and shared by a majority of its members regarding school organisational aspects that manifest themselves in daily work practices.

3. Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) in Theory and Research

School culture can be assessed either normatively (judging, i.e., whether a school has a good school culture or not, e.g., [31,32]) or descriptively (describing, for example, by means of observations or other qualitative approaches, e.g., [32,33]). In the context of school development, Fend [34] uses a normative approach because school culture is understood as an indicator of school quality. Some studies combine the normative and descriptive approaches in capturing school culture, such as the comprehensive model of school culture by Schoen and Teddlie [35]. With this model, an important step has been made in addressing the concept of school culture in empirical school research. The authors simultaneously considered the norms and values of schools, made them comparable, and related them to other variables such as student achievement.

To enable an assessment of school culture from an organisational psychology perspective [30] and to show differences between school culture types, the Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) can be used, which is an empirical–analytical approach to measure school culture. It corresponds to the theoretical assumption of organisational development (e.g., [24,27]). The model allows to capture the fundamental norms and values of an organisation from the perspective of the employees, i.e., the teachers. With the OCAI, Cameron and Quinn [36] offer an instrument for diagnosing organisational culture which, according to the authors, is both easy to use in practice and meets the requirements of scientific analysis of culture using quantitative methods.

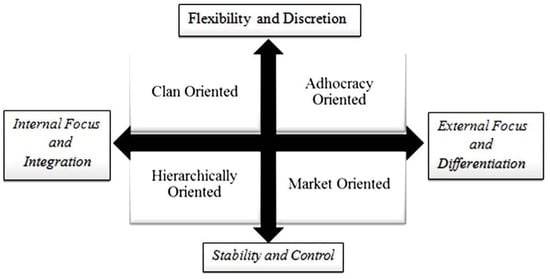

The theoretical model OCAI postulates opposing dimensions (control and stability vs. flexibility and discretion; internal vs. external focus) for the consideration of organisational values, as well as the four quadrants. Following Quinn and Rohrbaugh [37], Cameron and Quinn [36] linked the four value quadrants to specific culture types and at the same time developed the OCAI to describe organisational culture with respect to different organisational domains from the perspective of the employees (see Figure 1). In each of the four cultures, different values and norms are regarded as adequate and purposeful, so that the different types of culture can be identified and distinguished from each other by comparing these underlying values.

Figure 1.

Competing Values Framework Created by Quinn and Rohrbaugh [37].

Clan school culture is characterised by cooperation and support. There is a strong community and members work together to achieve common goals.

Adhocracy school culture is characterised by creativity, innovation, and discretion. Individual opinions and ideas are encouraged and freedom and autonomy are valued.

Market school culture is characterised by competition and achievement. Pressure to succeed, efficiency, and results are emphasised.

Hierarchy school culture is characterised by structure and order. There are clear rules and responsibilities and decisions are made top down.

The goal of this model is to assess the dominant value patterns of a school; even if the school has values in all four school culture types, a dominant, more pronounced school culture can prevail, which is assumed to overshadow the other types.

This description shows that the Clan culture is associated with a focus on internal processes and high flexibility, whereas the opposing Market culture is driven by external factors and stability. Applying this model to the school context highlights how some schools may be more focused on their internal structures and processes and neglect the influence of their specific context.

In early studies, the OCAI was used primarily in US universities and colleges [38]. It appears that regardless of individual factors (age, gender, job title, etc.), Clan culture is favoured by most college and university employees. Studies in elementary schools from Israel [39], India [40], and Germany [15,41] reached similar conclusions. The original version of the OCAI has been used in a wide range of organisations around the world [42]. The reliability and validity of the survey instrument—also in translations—have been proven by several studies in different countries and organisational contexts (e.g., [43]). However, its use in school contexts and especially in German-speaking countries is relatively new (e.g., [15]). According to Heritage et al. [44], the instrument is particularly suitable for investigating the current status quo and less suitable for measuring a desired, so-called “ideal culture”.

Berkemeyer et al. [45] further distinguish the different cultural patterns formed by different expressions of the four types using a latent class analysis. The results showed that most of the schools were characterised as having a dominant Clan culture. Another German study by Demski et al. [10] examining 109 schools using the OCAI shows that the assessment of the teacher teams and their school principals is statistically similar. Furthermore, Clan culture is again the most common across school types (comprehensive, elementary, and special schools), while Market orientation is more dominant in secondary schools.

To sum up, the empirical findings show that the Clan type is the most dominant in the school context. Values of the Clan culture, such as goal orientation and collegiality, may be related to the implementation of reforms in schools. Clan culture can indicate a collaborative work environment, which can be considered a good starting point for reform. Contrarily, a desire for consensus may impede the motivation to implement new ideas.

4. On the Association between School Culture and Development Processes

Various studies—some also using the OCAI instrument—describe which aspects of school culture might be important for school development [1,3,46,47]. Demski et al. [10] found that there is a statistically relevant relationship between Clan or Adhocracy school culture and teachers’ evidence-based actions. This means that teachers of these culture types are more oriented to scientific data and facts about school development and teaching. Furthermore, research indicates that Adhocracy culture is related to school development processes, which in turn have a positive impact on teachers’ professionalisation process and competencies (e.g., [48,49,50]).

Other studies with different theoretical and methodological approaches (other than OCAI) find that collaborative culture is characterised by support and that appreciation has a beneficial effect on teachers’ acceptance of change and engagement in development projects (e.g., [51]). The extent of participation and reflective dialogue in the teacher team influences their commitment as well as their capacity for organisational learning and change (e.g., [52,53,54]). Supportive and appreciative leadership (employee-oriented leadership) strengthens employees’ trust and their willingness to change [55]. Shann [56] showed that teachers’ job satisfaction is connected to their satisfaction with the curriculum, the decision making, and their opportunities of participation in their own school. Therefore, collegial support in a school might be related to how teachers view the implementation success of curriculum reforms. The findings of Louis et al. [57] indicate that the characteristics of a hierarchical school culture appear to be less favourable in the context of reform processes. Rather, it is emphasised that school reforms are more successful when school leaders succeed in creating both learning and community in their schools and thus lead from the centre rather than from a hierarchical position. In the area of MIL, Tondeur et al. [58] show that schools with an innovative school culture use computers in lessons significantly more often. In terms of their character traits, these schools correspond to the clan and adhocracy culture.

In summary, various studies indicate that the Clan and Adhocracy culture, or the characteristics of those types, plays an important role for the participation of teachers in curriculum reforms. As the previous research indicates, the Clan culture type seems to be the most common in schools. However, there is little research on the extent to which school culture plays a role in teachers’ evaluation of curriculum reforms. It seems plausible that schools where teachers collaborate frequently and engage actively in organisational learning have a different approach to curriculum reforms [11]. In Swiss schools in particular, no research has yet been conducted on school culture using the OCAI model, nor on the relationship between the associated school culture types and curriculum development processes. The current implementation of the MIL curriculum thus offers an opportunity to explore this research gap. This study intends to explore how the schools can be grouped into specific clusters that depend on teachers’ ratings of the typologies of school culture. Additionally, the connection between the different types of school culture and the perceived success of curriculum reform will be investigated from the teachers’ perspectives.

5. The Present Study: Research Questions and Hypotheses

The present study aims at investigating the relationship between teachers’ perceived school culture and the perceived success of curriculum reform. Therefore, this study pursues the following main research question and sub-questions: How is school culture associated with the perceived success of curriculum reform?

- How are the four culture types distributed in Swiss schools?

- Is there an association between these culture types and a teacher’s perceived success of the curriculum reform?

- Are there other profiles of school culture and to what extent do those exploratively generated clusters of school culture correspond with the OCAI model?

School culture contributes essentially to school development processes and the sustainability of curriculum implementation [10]. Yet not all perceived culture types are in the same way effective for fostering curriculum implementation processes. In this study, we examine the following hypotheses.

H1.

Following previous research (e.g., [10,49]) that indicates that Clan culture is considered the dominant culture, especially in educational institutions, we assume that the Swiss schools most frequently correspond to the type Clan, which assumes people- and team-oriented leadership and development.

H2.

For research question two, we assume, based on previous research (e.g., [10,49]), a positive correlation between the school culture types Clan and Adhocracy and the perceived success of curriculum reform. Moreover, we also assume a negative or no correlation between the school culture types Hierarchy and Market and the perceived success of curriculum reform.

H3.

In addition to the four types, further profiles of school culture can be identified that are not based on the dominant culture. Thus, those differences between the so-called school clusters can be described and statistically distinguish the schools from each other. Differences between those exploratively found school culture profiles and teachers’ perceived success of curriculum reform are expected.

6. Methods

6.1. Design and Sample

This research is embedded in a larger research project “Reform@Work”, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant #188867). A cross-sectional design was applied. Twenty-five schools (kindergarten to sixth grade) from German-speaking cantons in Switzerland were surveyed. A total of 348 teachers (86.1% female, 13.6% male, 0.3% non-binary) participated in the online survey in the school year 2022/23. The teachers were between 22 and 63 years old (M = 41.63, SD = 10.43). Their working experience was between 1 and 45 years (M = 16.15; SD = 10.80). Participation was voluntary and anonymity guaranteed.

6.2. Measures

6.2.1. School Culture Type

The Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) [36] attempts to capture the respective characteristics of the four culture types (Hierarchy, Clan, Adhocracy, Market) based on the six organisational categories: dominant characteristics, organisational leadership, management of employees, organisation glue, strategic emphasis, and criteria of success. The six categories of culture are scored using a 100-point range system related to four different statements (e.g., “Our school is a very dynamic and exploratory place. The teaching team is ready to take risks or new paths”) that relate to the four school culture types [45]. Cameron and Quinn [36] speak of a particularly strong culture, respectively a dominant culture from an average of 50 points or more.

To test the instrument for assessing school culture, the German-adapted version of the OCAI (OCAI-SK; [15]) with 24 items was used in the project “Reform@Work” (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Items of the OCAI-SK and the corresponding cultural type for the organisational moment “essential characteristics”.

6.2.2. Perceived Curriculum Reform Success

The dependent variable “perceived curriculum reform success” is operationalised via teachers’ satisfaction with curriculum reform [59]. It measures the extent to which teachers are satisfied with the current state of implementation of the MIL curriculum in their school. It is based on three items reflecting the satisfaction with the reform in reference to (a) the state/government regulations, (b) other schools, and (c) the relevance of the curriculum reform for student learning ([59]; scaling: 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree; e.g., “I think that the MIL reform is implemented well at our school today according to the cantonal and national guidelines”).

6.3. Reliability Analyses of the Used Measures

We examined whether our data fulfilled several requirements for data aggregation on a school level and for the cluster analysis (see Table 2). Specifically, we checked the values of ICC(1) [60], the average deviation index ADM [61], and the McDonald’s omega coefficient [62]. These figures indicated that a substantial amount of variance can be explained by the school level and indicate the satisfactory reliability of the constructs [62].

Table 2.

Measures of reliability and interrater agreement and sample items for all variables.

Index

In order to estimate group-level constructs reliably from the individual ratings of the respective group members [60], a significant ICC(1) is needed [63]. To calculate the ICC, only schools with 10 or more teachers were included in the calculation. The average deviation index ADM [61] is a measure of within-group agreement, which, in our case, quantifies individual teachers’ deviations from the school mean in the original scale metric. The composite reliability coefficients (McDonald’s omega) can be interpreted like traditional reliability estimates (see [62], p. 158).

7. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Science IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27; [64]). The number of missing values per item was low, reaching a maximum of 13.51% in four items of the OCAI-model scale and a maximum of 14.94% in one item of the scale perceived success of the curriculum reform. No systematic missing patterns were revealed. The missing values were not replaced in the analysis.

Data analysis consisted of three main steps. First, the construct validity (reliability of the measures with Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, and the intra-class correlation) were assessed (see Table 2).

In the second step, a Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between the school culture types and the perceived success of the curriculum.

The cluster analysis groups the schools according to their average values concerning the four school culture types. We assume that the expression of the mean values per school should not only represent a dominant cultural value but should show how high the agreement with the different types was rated. Similarly, we assume that the dominance hypothesis does not differentiate enough between schools and, therefore, cluster analysis is necessary. In cluster analysis, natural groups are formed. The non-hierarchical K-means method allows us to define in advance the number of clusters calculated based on sample size, resulting in two clusters. Higher cluster solutions are tested against the two-cluster solution. By applying one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), it can be ensured that the clusters are significantly different from each other. Each cluster should be as homogeneous as possible within itself, while the clusters should differ from each other as much as possible. In the final step, a Mann–Whitney U-Test was calculated to determine if there were differences in teachers’ perceived success of the curriculum reform between the two school culture profiles [65].

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

The aggregated data includes 25 schools. As shown in Table 3, the school culture type Clan is the most dominant on the school level (M = 37.62), followed by Adhocracy and Hierarchy. Yet also the standard deviation (SD = 8.28) between the ratings is higher than in all other culture types. The lowest ratings of the four types are placed on the Market type (M = 12.02, SD = 4.81). Furthermore, the mean score of the scale “perceived success of the curriculum reform” is 2.96 (SD = 0.54).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the aggregated data with the 25 schools.

8.2. Relationship between the Found School Culture Types and the Perception of Curriculum Reform Success

Correlation coefficients and p-values regarding the relationship of school culture types and perceived curriculum reform success can be found in Table 4. We found no statistically significant relationship between the school culture types Clan (r = 0.19, p = 0.37, n = 25), Adhocracy (r = −0.30, p = 0.14, n = 25), and Market (r = −0.21, p = 0.32, n = 25) and teachers’ perception of curriculum reform success. However, a negative and statistically significant correlation between the school culture type Hierarchy and the perception of curriculum reform success was found (r = −0.42, p = 0.03, n = 25), suggesting that the higher the level of the school culture type Hierarchy in a school, the lower the perceived success of curriculum reform.

Table 4.

Correlations for study variables.

The Clan school culture type is statistically significantly negatively correlated with the Market school culture type (r = −0.69, p < 0.01, n = 25) and the Hierarchy school culture type (r = −0.60, p < 0.01, n = 25). Furthermore, the school culture types Market and Hierarchy correlate negatively with the other two school culture types, Adhocracy and Clan; this can be explained by their opposing orientations. As mentioned in before, the OCAI model postulates opposing dimensions, where Market and Hierarchy have a stable and controlled focus, whereas Adhocracy and Clan have a focus that is flexible and discretionary.

8.3. Cluster Analysis of the School Culture Types

By applying a cluster analysis, the schools were grouped into clusters that correspond to the average mean of the school culture types described in Section 5. The cluster analysis showed that the schools can be divided into two different clusters (see Table 5). One-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) shows that the clusters differ significantly with regard to the expression of the culture types Clan: F(1, 23) = 32.77, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.5876; Market: F(1, 23) = 13.57, p 0.001, η2p = 0.3711; and Hierarchy: F(1, 23) = 16.02, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.4106). No significant differences between the clusters can be seen regarding the type Adhocracy (F(1, 23) = 9.97, p < 0.232, η2p = 0.3024).

Table 5.

Cluster analysis of school culture.

The first cluster can be defined as Collegial Associates. As shown in Table 4, 17 of the 25 schools fall into this cluster. In this cluster, the Clan type is the most pronounced compared to the second cluster, reaching an average mean of M = 60.00. Even though this would mean, according to Cameron and Quinn [36], that the dominant culture in this cluster is the clan school culture type, the remaining expressions on the other school culture types must also be highlighted to accurately describe the cluster. In summary, the school has a strong Clan culture characterised by collaboration, teamwork, and a strong sense of community. Moreover, schools in the cluster Collegial Associates are less focused on external than on internal processes, which may lead to a very low value in competitiveness (Market) and a rather flat hierarchy (Hierarchy) where participative decision making is encouraged.

We call the second cluster Competitive Organisations. Eight schools belong to this cluster. Compared to the Collegial Associates cluster, the mean values of these schools in Market are more than three times higher and in Hierarchy more than twice as high. This indicates, according to the theory, that schools in this cluster are highly regulated and structured (Hierarchy) and formal processes are important in day-to-day activities. Moreover, the schools are strongly oriented on external demands and may, therefore, be more focused on efficiency and accountability (Market). Importantly, the cluster analysis shows that the Clan school culture is considerably less pronounced in these schools.

A Mann–Whitney U-Test was perfomed to determine if there were differences in teachers’ perceived success of curriculum reform between the two school culture profiles (Collegial Associates and Competitive Organisations). There was no statistically significant difference in teachers’ perceived success of curriculum reform between the two school culture profiles (U = 47.000, Z = −1.224, p = 0.221).

9. Discussion

Since the success or failure of curriculum reforms depends on how well it is compatible with the school culture [66], the relationship between the school culture and the perceived success of the school reform, i.e., the satisfaction of teachers with the implementation of the MIL curriculum, was explored in this study following Cameron and Quinn’s [36] OCAI model.

The results show that in the participating Swiss schools, the Clan culture is the most dominant type of school culture. According to the dimensions of the OCAI model, this culture type can be characterised as participative with an internal focus. This largely corresponds with previous research (e.g., [39,41,49]). The large proportion of schools in the Clan culture could also be because the schools that took part in the “Reform@Work” project are small to medium-sized, which enables a closer relationship between teachers, pupils, and parents, which may promote a Clan school culture. In future research, the relationship between school size and school culture typification should be controlled for. The results are in line with hypothesis 1.

Furthermore, the study examined the relationship between the types of school culture according to OCAI [36] and the perception of the success of curriculum reform. By applying Pearson’s correlation analysis, no significant correlation between the school culture types Clan and Adhocracy and the teacher’s perception of curriculum reform success could be found. This means that neither of the two school culture types is associated with more or less teacher perceived success when implementing the MIL curriculum. Therefore, the first part of hypothesis 2, which states that the school culture types Clan and Adhocracy positively correlate with the perception of curriculum reform success, must be rejected. This is not in line with previous research, which assumed that participation and the possibility of co-decision motivate employees to actively participate in change processes (e.g., [52]). Similarly, no statistically significant correlation between the school culture type Market and the teacher’s perception of curriculum reform success was detected. Nevertheless, there is a statistically negative correlation between the Hierarchy school culture type and perceptions of curriculum reform success. The second part about the assumed negative or neutral correlation between Hierarchy and Market with the curriculum reform success can be confirmed. Wilkins [67] argues that change in organisations often fails if it does not fit the existing culture. In contrast, Fend [68] and Gordon and Patterson [1] state that schools are able to interpret and adapt change so that it can be integrated into their cultures. This ability may explain why no correlations were found between the school culture types adhocracy, clan, and market, as schools adapt the introduction of new concepts, such as the MIL curriculum, to their context. Additionally, the lack of correlation between school culture types and the success of curriculum reform is explained by the fact that teachers rarely see themselves as part of the leadership team and feel overwhelmed by the tasks of school development, which leads to them not seeing themselves as responsible for the success of curriculum reform [69]. As expected, there was a negative correlation between the type of hierarchy and reform success, which confirms earlier studies (e.g., [57]). The negative correlation with the hierarchy type could be due to its rigid structures, which make innovation more difficult, as hierarchical schools are more resistant to curriculum reforms that challenge established structures. Apart from the decisive role of school leadership in school change processes, however, there is insufficient empirical research on how the school culture perceived by teachers and different leadership styles of principals affect reform initiatives [53]. In this regard, additional analysis could integrate leadership styles more explicitly to ascertain their influence on the school culture and reform outcomes. Future studies could consider including a more detailed examination of leadership roles within different school culture types.

Finally, since the values of the Clan culture type were expected to be high across all schools, the study aimed at identifying if there are other profiles of school culture in the sample of participating schools. The results reveal two further profiles of school culture types which, based on the distribution of the mean values, are called Collegial Associates and Competitive Organisations. The profiles of the school culture types in these clusters give clear indications of the focus of the schools. Most schools (17 of 25) are characterised as having a Collegial Associates culture approach, which focuses on internal relationships and processes. It is thus clear that those schools, in contrast to organisations in the free market economy, place a clearer focus on internal processes and the well-being of the people in the organisation than on the development of the entire organisation in its environment. The remaining schools (8 of 25) are characterised as Competitive Organisations. The sense of community (Clan) is less pronounced than in the first cluster; collaboration and teamwork are less emphasised. The different values of Market orientation mainly differentiate between the two types. This leads to the conclusion that those eight schools may be more prone to a bureaucratic structure, which was focused on very early in the development of school culture research [1]. The benefit of the cluster analysis is that it makes it possible to describe school culture profiles in which all four school cultures are taken into account, which may be more indicative of differences between the schools. Therefore, it can be concluded that the results are in line with hypothesis 3, which states that further profiles of school culture can be identified that are not based on the dominant culture. Yet, according to those results, it remains unclear whether the Competitive Organisations are the less favoured cluster of the two and what benefits such culture profile may hold for the individual schools in their individual contexts. Although differences between the two school culture profiles of Collegial Associates and Competitive Organisations were expected in terms of the teachers’ perceived success of curriculum reform, no statistically significant differences were found.

These results show, for the first time in the Swiss educational context, that the assessment of school culture types with the OCAI model according to Cameron and Quinn [36] is possible but not sufficiently differentiated among the schools, which is why a more in-depth analysis of the items using a cluster analysis, as in this study, is appropriate even though the two clusters are not associated with the perceived success of curriculum reform.

10. Study Limitations and Implications for Future Research

The generalisability of the results is limited due to the number of participating schools in Switzerland. Further studies could focus more on a large sample of teachers in schools to better tie in with international research on school culture. In the context of the global digitalisation of education, further studies could address this research desideratum, for example in the form of a cross-national comparison.

Since values and norms are often subconscious and difficult to capture by simple questionnaires, methods should be used that also allow insight into subconscious and habitual behaviour, such as participant observation or content analysis of interviews (e.g., [70]). By using such methods, it would be possible to explore important additional information based on how the entire system of shared values and norms defines interactions with school members and external parties [24].

Future studies should also consider the regional and contextual conditions of the schools [3], as well as the school size. For example, the ICT infrastructure of the schools was not taken into account in the study. Empirical data indicates that this is of minor importance [71]. Despite the need for a suitable digital infrastructure at school level, including access to digital tools such as end devices and internet access, these factors alone are not sufficient to motivate teachers to integrate technology into their classrooms or to achieve school reform success in this area [71]. The degree of technological equipment only correlates to a limited extent with actual use by teachers [72]. Nevertheless, infrastructure should also be included in future school reform studies, particularly in the area of digitalisation. These variables might have allowed for more explanatory approaches in the present study.

The research acknowledges the complexity of the concept of “success” in the context of curriculum reform by exploring how these dimensions are perceived by teachers, which affect their engagement and the overall success of the reform. In order to gain further and deeper insights to understand and compare successful implementation, qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) [73] should be included in future research. With these methods, it would be feasible to incorporate essential supplementary information addressing the varying reform requirements of different cantons. Additionally, a mixed-methods approach could be employed to capture perceptions from diverse stakeholders, including principals.

11. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Although the OCAI model has already been used in organisations in many countries [42], this study was the first to examine school culture in Swiss schools. The present study provides an overview of school culture types in Swiss schools regarding the new MIL curriculum. The participating Swiss schools in this study show that the Clan culture is also the most dominant type of school culture. Those schools can be characterised as participative with an internal focus. Even though it was expected, based on the empirical findings (e.g., [10]), that the school culture types Clan and Adhocracy would be positively correlated with teachers’ perceived curriculum reform success, no statistically significant relationship was found. The school culture type Market also showed no statistical correlation with teachers’ perceived curriculum reform success. Nevertheless, a negative correlation between the school culture type Hierarchy and perceived curriculum reform success was found. During this study, two further profiles of school culture were identified: Collegial Associates and Competitive Organisations. The findings of the exploratory cluster analyses are highly significant, as they can be used as a starting point for school development processes. The lack of alignment between external requirements and internal processes is one of the most common barriers to successful school and curriculum development processes [74]. Knowledge of one’s own school culture is therefore crucial to plan and implement curriculum reforms effectively. Leaders in the school context may benefit from knowing their culture type to improve the likelihood of implementation. The results of the study indicate that characteristics of the “Hierarchy” school culture type, such as the fact that decision making rests with principals and administrators and that teachers have little to no voice, are negatively related to the perceived success of curriculum reform. Schools and their administrators should, therefore, avoid a strong focus on hierarchical school culture types when implementing reforms, such as the new MIL curriculum. Principals in particular, should make decision making participatory and establish co-determination opportunities about MIL for all actors in the school (e.g., having a voice in the selection of teaching materials for MIL). In addition, universities, training companies, and providers of continuing education can adapt their offerings to individual teachers or schools, considering their culture and satisfaction with curriculum reform.

As discussed in chapter 1, digital and media-related content will be increasingly integrated into school curricula. Given that the module curriculum was formulated in 2015 and artificial intelligence (AI) has only recently emerged in the education sector, it can be anticipated that, although the current school reform appears to be concluding, AI will initiate new school development processes. In addressing AI, the definition provided by the Association of College and Research Libraries [75] should be referenced, emphasising the necessity for individuals to possess the skills to “recognize when information is needed and have the ability to find, evaluate, and use the needed information effectively” (p.2). Future research should therefore investigate the school development processes instigated by AI and examine potential revisions to the competence requirements of the MIL module curriculum.

The study adds theoretical value to the field of school culture research by investigating Cameron and Quinn’s [36] school culture types further through exploratory cluster analysis and, therefore, offers an in-depth analysis of the profiles of school culture in Swiss schools. Finally, the analysis of school culture in relation to school reform success offers a revealing insight not only for the education system in Switzerland—both from a theoretical and practical perspective—but also for education systems worldwide that are adapting to digital transformation and identifying successful implementation strategies for necessary reforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and M.J.; methodology, M.G. and M.J.; software, M.G. and M.J.; validation, M.G.; formal analysis, M.J.; investigation, M.G. and M.J.; resources, M.G. and M.J.; data curation, M.G. and M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and M.J.; writing—review and editing, M.G.; visualization, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the larger Swiss National Science-funded project “Reform@Work” (Grant # 188867).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Project administration and funding acquisition was done by Gerda Hagenauer and Ueli Hostettler. Published with the support of the Bern University of Teacher Education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gordon, J.; Patterson, J.A. “It’s what we’ve always been doing.” Exploring tensions between school culture and change. J. Educ. Chang. 2008, 9, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolff, H.-G. Schulentwicklung Kompakt: Modelle, Instrumente, Perspektiven, 3rd ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Beales, B. Contrasting perspectives on organizational culture change in schools. J. Educ. Chang. 2011, 12, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frau-Meigs, D.; Velez, I.; Michel, J.F. (Eds.) Public Policies in Media and Information Literacy in Europe: Cross-Country Comparisons; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Educa.ch. Lehrpläne [Curricula]. 2020. Available online: https://www.educa.ch/de/digitalisierung-bildung/ (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Grgić, M. Competencies and beliefs of Swiss teachers with regard to the modular curriculum ‘Media and ICT’. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2023, 5, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenert, S.; Whitaker, T. School Culture Rewired: How to Define, Assess and Transform It; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hinde, E.R. School culture and change: An examination of the effects of school culture on the process of change. Essays Educ. 2005, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bümen, N.T.; Holmqvist, M. Teachers’ sense-making and adapting of the national curriculum: A multiple case study in Turkish and Swedish contexts. J. Curric. Stud. 2022, 54, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demski, D.; van Ackeren, I.; Clausen, M. Zum Zusammenhang von Schulkultur und evidenzbasiertem Handeln—Befunde einer Erhebung mit dem “Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument” [On the relationship between school culture and evidence-based practice—Findings from a survey using the “Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument”]. J. Educ. Res. Online 2016, 8, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, N.; Savage, C.; Gräsel, C.; Wacker, A. Who buys into curricular reforms and why? Investigating predictors of reform ratings from teachers in Germany. J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 53, 802–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppsch, B. Schulkultur Durch Kulturelle Schulentwicklung Gestalten: Von der Möglichkeit, Lernförderliche Haltungen zu Entwickeln [Shaping School Culture through Cultural School Development: From the Possibility of Developing Supportive Attitudes to Learning]. Kulturelle Bildung Online. 2019. Available online: https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/schulkultur-durch-kulturelle-schulentwicklung-gestalten-moeglichkeitlernfoerderliche (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Deal, T.E.; Peterson, K.D. Shaping School Culture: The Heart of Leadership; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wiater, W. Schulkultur—Ein Integrationsbegriff für die Schulpädagogik? [School Culture—An Integrative Concept for School Pedagogy?] . In Perspektive Schulpädagogik. Anspruch Schulkultur: Interdisziplinäre Darstellung eines Neuzeitlichen Schulpädagogischen Begriffs; Seibert, N., Ed.; Klinkhardt: Tacoma, WA, USA, 1997; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Müthing, K. Organisationskultur im schulischen Kontext: Theoriebasierter Einsatz eines Instrumentes zur Erfassung der Schulkultur [Organizational Culture in the School Context: Theory-Based Use of an Instrument for the Assessment of School Culture]. Doctoral Dissertation, Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany, 2013. Available online: https://eldorado.tu-dortmund.de/handle/2003/30369 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Demski, D. Evidenzbasierte Schulentwicklung: Empirische Analyse Eines Steuerungsparadigmas [Evidence-Based School Development: Empirical Analysis of a Governance Paradigm]; Springer VS: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holtappels, H.G.; Voss, A. Organisationskultur und Lernkultur. Zusammenhänge zwischen Schulorganisation und Unterrichtsgestaltung am Beispiel selbständiger Schulen [Organizational Culture and Learning Culture. Relationships between School Organization and Instructional Design using the example of Independent Schools]. In Jahrbuch der Schulentwicklung; Bos, W., Holtappels, H.G., Pfeiffer, H., Schulz-Zander, R., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; Volume 14, pp. 247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, F.U.; Reh, S.; Fritzsche, B.; Idel, T.S.; Rabenstein, K. Lernkultur: Überlegungen zu einer kulturwissenschaftlichen Grundlegung qualitativer Unterrichtsforschung [Learning Culture: Reflections on a Cultural Scientific Foundation of Qualitative Classroom Research]. Z. Erzieh. 2008, 11, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C. Rituelle Lernkulturen: Eine Einführung [Ritual Cultures of Learning: An Introduction]. In Lernkulturen im Umbruch; Wulf, C., Althans, B., Blaschke, G., Ferrin, N., Göhlich, M., Jörissen, B., Mattig, R., Nentwig-Gesemann, I., Schinkel, S., Tervooren, A., et al., Eds.; VS Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nerdinger, F.W.; Blickle, G.; Schaper, N. Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie [Work and Organisational Psychology]; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg-Stürm, J. Organisation und Organisationaler Wandel: Eine Theoretische Erkundung aus Konstruktivistischer Sicht [Organisation and Organisational Change: A Theoretical Exploration from a Constructivist Perspective]; VS Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.R.; Bouncken, R.B. Organisation: Theorie, Design und Wandel [Organization: Theory, Design and Change]; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenert, S. Shaping a new school culture. Contemp. Educ. 2000, 71, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organisationskultur: The Ed Schein Corporate Culture Survival Guide; EHP: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Kultur als historischer Begriff [Culture as a Historical Concept]. In Gesellschaftsstrukturund Semantik; Luhmann, N., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- van Ackeren, I.; Block, R.; Kullmann, H.; Sprütten, F.; Klemm, K. Schulkultur als Kontext naturwissenschaftlichen Lernens. Allgemeine und fachspezifische explorative Analysen [School Culture as a Context for Science Learning. General and Subject-specific Explorative Analyses]. Z. Pädagogik 2008, 54, 341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Esslinger-Hinz, I. Die Schule zwischen Reform und Tradition. In Spannungsfelder der Erziehung und Bildung; Esslinger-Hinz, I., Fischer, H.J., Eds.; Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Hohengehren, Germany, 2008; pp. 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Die Kontingenzperspektive der Kultur: Kulturbegriffe, Kulturtheorien und das kulturwissenschaftliche Forschungsprogramm [The Contingency Perspective of Culture: Cultural Concepts, Cultural Theories and the Cultural Studies Research Programme]. In Handbuch der Kulturwissenschaften; Jaeger, F., Liebsch, B., Rüsen, J., Eds.; Metzler: Munich, Germany, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, W. Schulkulturen—Die Schule als symbolische Sinnordnung [School Cultures—The School as a Symbolic Order of Meaning]. Z. Pädagogik 2008, 54, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Duncker, L. Lernen als Kulturaneignung [Learning as Cultural Appropriation]; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fend, H. Qualität im Bildungswesen [Quality in the Education System]; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, L.T.; Teddlie, C. A new model of school culture: A response to a call for conceptual clarity. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2008, 19, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrio, A.A. An Organizational Culture Assessment Using the Competing Values Framework: A Profile of Ohio State University Extension. J. Ext. 2003, 41, 4. Available online: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol41/iss2/4/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Kheir-Faddul, N.; Bibu, N.; Nastase, M. The principals’ perception of their values and the organizational culture of the junior high schools in the Druze sector. Rev. Manag. Comp. Int. 2019, 20, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennatuserry, J.C.; Elangovan, N.; George, L.; Thomas, K.A. Clan Culture in Organizational Leadership and Strategic Emphases: Expectations among School Teachers in India. J. Sch. Adm. Res. Dev. 2022, 7, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, R.; Berkemeyer, N.; Nachtigall, C. Schulkultur, Schulentwicklung und Schuleffektivität: Eine thüringenweite Zusammenhangsanalyse organisationsbezogener Kulturzuschreibungen, schulischer Netzwerkarbeit und Schülerleistung [School Culture, School Development, and School Effectiveness: A Thuringia-wide Interrelationship Analysis of Organization-Related Culture Attributions, School Networking, and Student Performance]. In Institutioneller Wandel im Bildungswesen; Hermstein, B., Berkemeyer, N., Manitius, V., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.A. Process for changing organization culture. In Handbook of Organizational Development; Cummings, T.G., Ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.S.; Seo, M.; Scott, D.; Jeffrey, M. Validation of the organizational culture assessment instrument: An application of the Korean version. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, B.; Pollock, C.; Roberts, L. Validation of the organizational culture assessment instrument. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkemeyer, N.; Junker, R.; Bos, W.; Müthing, K. Organizational cultures in education: Theory-based use of an instrument for identifying school culture. J. Educ. Res. Online 2015, 7, 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Azorín, C.; Fullan, M. Leading new, deeper forms of collaborative cultures: Questions and pathways. J. Educ. Chang. 2022, 23, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, T.T.; Song, L. A proposed framework for understanding educational change and transfer: Insights from Singapore teachers’ perceptions of differentiated instruction. J. Educ. Chang. 2020, 21, 595–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeffner, J. Professionalisierung Durch Schulentwicklung. Eine Subjektwissenschaftliche Studie zu Lernprozessen von Lehrkräften an Evangelischen Schulen [Professionalisation through School Development. A Subject-Scientific Study on Learning Processes of Teachers at Protestant Schools]; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, R.; Berkemeyer, N. Beziehungsstrukturen in schulischen Innovationsnetzwerken [Relational Structures in School Innovation Networks]. Z. Erzieh. 2014, 17, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhart, E. Schulentwicklung und Lehrerkompetenzen [School Development and Teacher Competences]. In Handbuch Schulentwicklung; Bohl, T., Helsper, W., Holtappels, H.G., Schelle, C., Eds.; Klinkhardt Verlag: Tacoma, WA, USA, 2010; pp. 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Jimmieson, N.; Griffiths, A. The impact of organizational culture and reshaping capabilities on change implementation success: The mediating role of readiness for change. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.E.; Woodward, C.A.; Shannon, H.S.; MacIntosh, J.; Lendrum, B.; Rosenbloom, D.; Brown, J. Readiness for organizational change: A longitudinal study of workplace, psychological and behavioral correlates. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 75, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Seashore Louis, K. Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 81, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seashore Louis, K.; Lee, M. Teachers’ capacity for organizational learning: The effects of school culture and context. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2016, 27, 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.; Simons, R. An examination of the antecedents of readiness for finetuning and corporate transformation changes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2006, 20, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shann, M.H. Professional Commitment and Satisfaction Among Teachers in Urban Middle Schools. J. Educ. Res. 1998, 92, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K.S.; Kruse, S.; Raywid, M.A. Putting teachers at the center of reform: Learning schools and professional communities. NASSP Bull. 1996, 80, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; Devos, G.; van Houtte, M.; van Braak, J.; Valcke, M. Understanding structural and cultural school characteristics in relation to educational change: The case of ICT integration. Educ. Stud. 2009, 35, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landert, C. Die Berufszufriedenheit der Deutschschweizer Lehrerinnen und Lehrer (2014): Bericht zur vierten Studie des Dachverbandes Lehrerinnen und Lehrer Schweiz (LCH) [The Job Satisfaction of Teachers in the German-speaking Part of Switzerland (2014): Report on the fourth Study of the Umbrella Organisation Teachers Switzerland (LCH)]. Report. 2014. Available online: https://www.lch.ch/fileadmin/user_upload_lch/Aktuell/Medienkonferenzen/141209_05_Studie_Charles_Landert_zur_Berufszufriedenheit.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Lüdtke, O.; Trautwein, U.; Kunter, M.; Baumert, J. Reliability and agreement of student ratings of the classroom environment: A reanalysis of TIMSS data. Learn. Environ. Res. 2007, 9, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Dunlap, W.P. Estimating interrater agreement with the average deviation index: A user’s guide. Organ. Res. Methods 2002, 5, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.J.S.; Marsh, H.W.; Nagengast, B.; Scalas, L.F. Doubly latent multilevel analyses of classroom climate: An illustration. J. Exp. Educ. 2014, 82, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mierlo, H.; Vermunt, J.K.; Rutte, C.G. Composing group-level constructs from individual-level survey data. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual, 6th ed.; Allen and Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz, J.; Schuster, C. Statistik für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler [Statistics for Human and Social Sciences] (7.; Vollständig Überarbeitete und Erweiterte Auflage); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Recepoglu, E. The significance of assumptions underlying school culture in the process of change. Int. J. Educ. Res. Technol. 2013, 4, 43–48. Available online: https://soeagra.com/ijert/ijertjune2013/7.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Wilkins, A.L. The culture audit: A tool for understanding organizations. Organ. Dyn. 1983, 12, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fend, H. Qualität und Qualitätssicherung im Bildungswesen. Wohlfahrtsstaatliche Modelle und Marktmodelle [Quality and Quality Assurance in Education. Welfare State Models and Market Models]. Z. Pädagogik 2000, 41, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Helterbran, V.R. Teacher leadership: Overcoming “I am just a teacher syndrome”. Education 2010, 131, 363–371. Available online: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ930607 (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative Content Analysis. Basics and Techniques]; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bingimlas, K.A. Barriers to the successful integration of ICT in teaching and learning environments: A review of the literature. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2009, 5, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossel, K.; Eickelmann, B. Teachers’ participation in professional development concerning the implementation of new technologies in class: A latent class analysis of teachers and the relationship with the use of computers, ICT self-efficacy and emphasis on teaching ICT skills. Large-Scale Assess Educ. 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, P.A. Qualitative Comparative Analysis: An Introduction to Research Design and Application; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M. Governance in der Schulentwicklung: Von der Autonomie zur Evaluationsbasierten Steuerung. Educational Governance [Governance in School Development: From Autonomy to Evaluation-Based Control. Educational Governance]; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Association of College & Research Libraries. Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. 2000. Available online: http://www.acrl.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/standards.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).